2 Attachment theory

Although it has long been recognised that humans form strong attachment relationships – not only between infant and mother, but also later in the lifespan via close friendships, sibling bonds, and romantic and marital relationships – the underlying processes have only been the subject of psychological enquiry since the middle of the twentieth century. Prior to this, it was widely thought that the main reason for attachments developing between mothers and their infants is that the mother satisfies ‘primary drives’ in the infant; especially the needs for sustenance, which the infant is not able to supply for herself.

However, is it simply the assurance of basic physical survival that human infants need, or is the relationship itself also important? A classic set of studies with young monkeys by Harry Harlow (1958) explored this question.

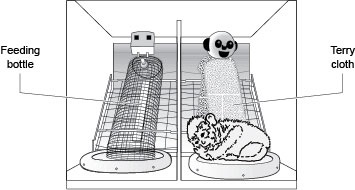

Harlow separated macaque infants from their mothers at birth and raised them in isolation cages. He found that close, frequent attention from human carers led to higher survival rates than care by captive natural mothers and that the infant monkeys learned to come to their human carers for food and comfort. He also noticed that the macaque infants often clung to the cloth pads that were used to cover the bases of the cages and they protested when these pads were removed for cleaning. He found that even a simple wire-mesh cone was often used as a refuge to cling to when the infants were frightened, and that this helped to boost survival rates. Covering the cone with cloth helped even more. Harlow then raised infant monkeys in isolation with only two simple ‘mother surrogate’ models available to them. In a key experiment, one of these ‘mothers’ was made from wire mesh and had an attached milk bottle from which the monkey could feed. The other ‘mother’ had a soft towelling surface but did not deliver any food.

The initial results were striking: the infant monkeys overwhelmingly preferred to cling to the ‘cloth mother’ rather than the ‘wire mother’ and when they were frightened, they almost always went straight to the cloth mother and held tightly to it – in spite of the fact that only the wire mother was their source of food. As the infants got older, these preferences increased rather than decreased. Furthermore, when these infant monkeys were put into an unfamiliar environment (a new room), the presence of their cloth mother greatly reduced their panic reactions. If the cloth mother was available, the infants would use it as what Harlow called a ‘base for operations’ (1958, p. 679), exploring the new room and its objects while periodically returning to cling to the mother surrogate. These findings were taken as strong evidence that there is another factor, stronger even than the provision of the basic necessity of food, which determines how macaque infants become attached to one object rather than another. Crucially, when Harlow moved the milk source to the cloth mother, this seemed to have no effect on the amount of clinging. Harlow had found that a bond with an object could provide security in the face of threat. What he called ‘contact comfort’ had emerged as being at least as significant as the basic needs for nourishment.

The research with different animals brought to the fore a series of questions that have been of great value in researching human development. The most important of these are as follows:

- Can infants bond with anyone or does it have to be the mother?

- What features of parenting are important for attachment?

- Does early parenting affect later life?

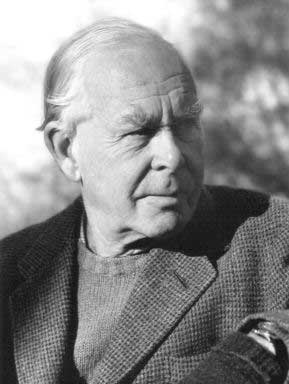

A central figure in research and theory addressing these questions is John Bowlby, whose work over four decades from 1940 established a strong, elaborated and productive theory, around the central concept of ‘attachment’. His interest in theorising attachment came about because of his involvement through case work and research with children who had mental health problems or were involved in criminality; so-called ‘juvenile delinquents’, to use a term in common use at the time. He recognised a common theme in the life histories of these children; that they had either lost one or both parents early in childhood through separation or death, or they had had very poor parenting. The term ‘maternal deprivation’ originated with Bowlby, based on this insight.