Greenberg and autonomy

While it has its roots in the nineteenth century, the approach to modern art as an autonomous practice is particularly associated with the ideas of the English critics Roger Fry (1866–1934) and Clive Bell (1881–1964), the critic Clement Greenberg (1909–94) and the New York Museum of Modern Art’s director Alfred H. Barr (1902–81). For a period this view largely became the common sense of modern art (O’Brian, 1986–95, 4 vols; Barr, 1974 [1936]). This version of modernism is itself complex. The argument presumes that art is self-contained and artists are seen to grapple with technical problems of painting and sculpture, and the point of reference is to artworks that have gone before. This approach can be described as ‘formalist’ (paying exclusive attention to formal matters), or, perhaps more productively drawing on a term employed by the critic Meyer Schapiro (1904–96), as ‘internalist’ (a somewhat less pejorative way of saying the same thing) (Schapiro, 1978 [1937]). According to Greenberg:

Picasso, Braque, Mondrian, Miró, Kandinsky, Brancusi, even Klee, Matisse and Cézanne derive their chief inspiration from the medium they work in. The excitement of their art seems to lie most of all in its pure preoccupation with the invention and arrangement of spaces, surfaces, colours, etc., to the exclusion of whatever is not necessarily implicated in these factors.

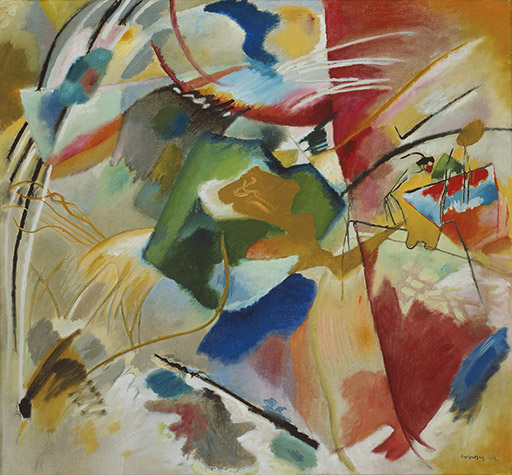

Rather than cloaking artifice, modern art, such as that made by Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) (see Figure 22), drew attention to the conventions, procedures and techniques supposedly ‘inherent’ in a given form of art. Modern art set about ‘creating something valid solely on its own terms’ (Ibid., p. 8). For painting, this meant turning away from illusion and story-telling to concentrate on the features that were fundamental to the practice – producing aesthetic effects by placing marks on a flat, bounded surface. For sculpture, it entailed arranging or assembling forms in space. In a series of occasional pieces, Greenberg produced an account of the coming to consciousness of artists (or art) in which this fundamental recognition of the nature of painting was brought to fruition. For him modern art began with Edouard Manet (1832–83), who was the first to recognise or emphasise the contradiction between illusion and the flat support of the canvas. Cézanne pushed this recognition much further and his legacy was picked up by Henri Matisse (1869–1954) and the Cubists and further developed by Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) and the interwar abstract painters and some Surrealists (particularly Joan Miró, 1893–1983), culminating in the Abstract Expressionist generation of American painters, who were his contemporaries. Greenberg represented this trajectory as the modernist ‘mainstream’ (Greenberg, 1993 [1960]).

It important to understand that the account of autonomous art, however internalist it may seem, developed as a response to the social and political conditions of modern societies. In his 1939 essay ‘Avant-garde and kitsch’, Greenberg suggested that art was in danger from two linked challenges: the rise of the dictators (Stalin, Mussolini, Hitler and Franco) and the commercialised visual culture of modern times (the kitsch, or junk, of his title). Dictatorial regimes turned their backs on ambitious art and curried favour with the masses by promoting a bowdlerised or debased form of realism that was easy to comprehend. Seemingly distinct from art made by dictatorial fiat, the visual culture of liberal capitalism pursued instant, canned entertainment that would appeal to the broadest number of paying customers. This pre-packaged emotional distraction was geared to easy, unchallenging consumption. Kitsch traded on sentimentality, common-sense values and flashy surface effects. The two sides of this pincer attack ghettoised the values associated with art. Advanced art, in this argument, like all human values, faced an imminent danger. Greenberg argued that, in response to the impoverished culture of both modern capitalist democracy and dictatorship, artists withdrew to create novel and challenging artworks that maintained the possibility for critical experience and attention. He claimed that this was the only way that art could be kept alive in modern society. In this essay, Greenberg put forward a left-wing sociological account of the origins of modernist autonomy; others came to similar conclusions from positions of cultural despair or haughty disdain for the masses.

The period from around 1850 onwards has been tumultuous: it has been regularly punctuated by revolutions, wars and civil wars, and has witnessed the rise of nation states, the growth and spread of capitalism, imperialism and colonialism, and decolonisation. Sometimes artists tried to keep their distance from the historical whirlwind, at other moments they flung themselves into the eye of the storm. Even the most abstract developments and autonomous trends can be thought of as embedded in this historical process. Modern artists could be cast in opposition to repressive societies, or mass visual culture in the west, by focusing on themes of personal liberty and individual defiance. The New York School championed by Greenberg coincided with this political situation and with the high point of US mass cultural dominance – advertising, Hollywood cinema, popular music and the rest. In many ways, the work of this group of abstract painters presents the test case for assessing the claim that modern art offers a critical alternative to commercial visual culture. It could seem a plausible argument, but the increasing absorption of modern art into middle-class museum culture casts an increasing doubt over these claims. At the same time, the figurative art that was supposed to have been left in the hands of the dictators continued to be made in a wide variety of forms. If figurative art had been overlooked by critics during the high point of abstract art, it made a spectacular comeback with Pop Art.

Greenberg’s story was particularly influential in the period from the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s. He produced a powerful synthetic account of developments or changes in art, but it was always a selective narrative. Even in the case of the paradigmatic example of Cubism, it is possible to see other concerns. Whereas the internal focus concentrated on the flattening of picture space through the use of small ‘facet planes’, art historians have recently paid a lot of attention to the way Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Georges Braque (1882–1963) engaged with the signs and materials of mass culture: their inclusion of newspaper cuttings, handbills, cinema tickets and the like. Cubism can be viewed as an experiment with the internal or formal concerns of art for a small audience of cognoscenti, and there is no denying that it is this, but embedded in this work is an engagement with the new forms of visual culture.