2.4.2 Vasari’s legacy

Further studies of Raphael and other Renaissance artists have challenged Vasari’s legacy on various fronts:

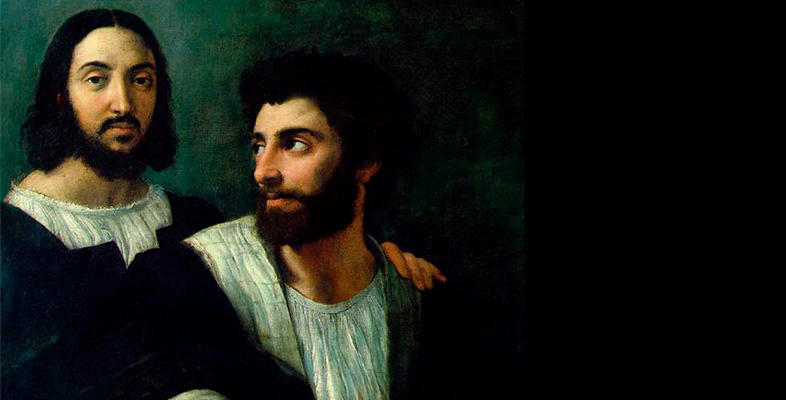

- Bette Talvacchia’s Raphael (2007) is a relatively recent monograph, written as is usual to present the artist’s complete oeuvre, but with an updated methodology that contests the ‘sweet, saccharine or, a more modern variant, boring’ (p. 10) image of the artist handed down by Vasari and others.

- Rudolf and Margot Wittkower’s Born under Saturn: The Character and Conduct of Artists (1963) is a classic text that builds on earlier work by Von Schlosser and Kris and Kurz, but from a less scholarly angle. It is particularly interested in the history of the melancholic artistic persona from Michelangelo to the bohemians.

- Catherine Soussloff’s ‘Lives of poets and painters in the Renaissance’ (1990) continues in the vein of Kris and Kurz by showing how Renaissance biographies of artists are modelled on those of poets; they follow literary conventions rather than offer true accounts of the artist’s style and intentions.

- Patricia Rubin’s Giorgio Vasari: Art and History (1995) was ground-breaking for its analysis of Vasari’s biographies not as a factual narrative but as an artful work of literature. Her chapter on Raphael ‘the new Apelles’ considers in detail how Vasari models Raphael as a courtier-painter who successfully rids his profession of the taint of manual labour.

- Piers Britton’s ‘Raphael and the bad humours of painters in Vasari’s Lives of the Artists’ (2008) underscores the influence of medical theories about human temperaments in Vasari’s Lives. It argues that Vasari’s description of Raphael emphasises the ability to keep his humours in balance, avoiding the problems caused by an excess of blood and bile in other artists (such as the melancholic Michelangelo).