Confessions of an English Opium Eater original manuscript, magazine publication and finished book.

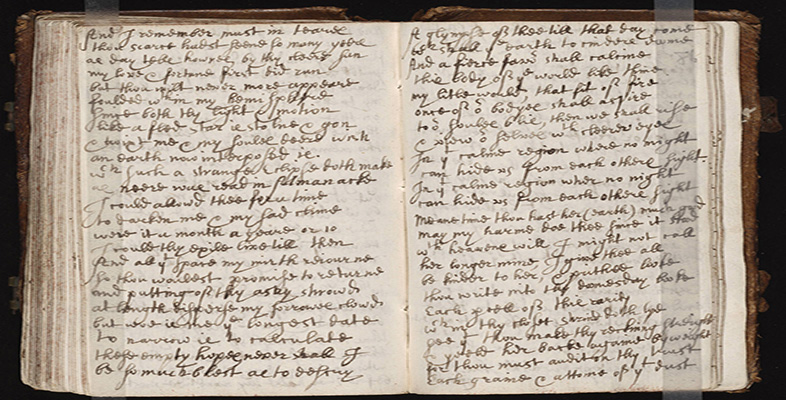

Thomas De Quincey wrote Confessions of an English Opium Eater by hand and the original manuscript still survives. It was bought by the fifth Earl of Rosebery, sold by the seventh Earl, owned for a while by the British Rail Pension Fund, and is now held at the Wordsworth Library at Dove Cottage in the Lake District.

Of course, De Quincey’s work would hardly be known today if that was the only copy. There’s a limit to how many people could squeeze into Dove Cottage and take turns reading the manuscript. De Quincey wrote his Confessions knowing that they would be quickly turned into something which could be sold to thousands of people and read by many more.

The publishing industry in the nineteenth century was changing quickly as new steam-driven printing presses made it quicker and cheaper to produce large numbers of books, newspapers, and magazines. However, printing was still a skilled trade and many different people’s work were needed before Confessions could appear either in The London Magazine in 1821 or on its own as a book in 1822.

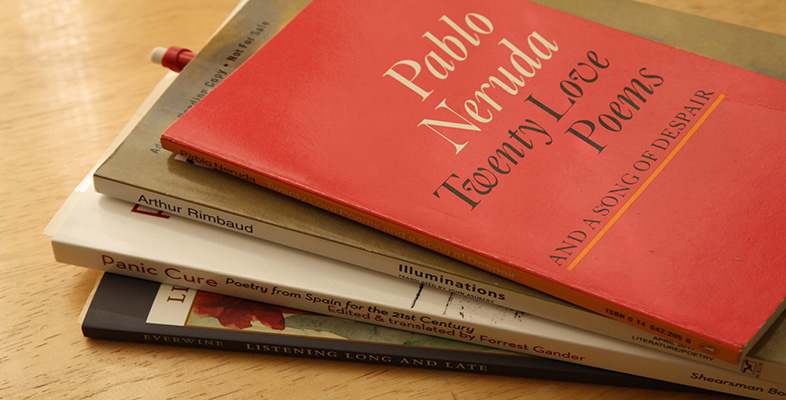

The first person to contribute after De Quincey was John Taylor who, as editor of The London Magazine, made a few small changes. Then the manuscript was sent to the printers. In fact they received small sections of the manuscript as De Quincey wrote them, printing the beginning before he had written the end. The most demanding job in the print house was that of the compositor or typesetter. These men had to read De Quincey’s manuscript, make sense of his corrections and changes, and then create the text to be printed by placing pieces of metal type on a rack, in order letter by letter. They did more than just reproduce what De Quincey had written. As was expected, they made changes to his punctuation and spelling and corrected what looked like mistakes. This was part of their job. When the typesetters were finished, other workers applied ink to the assembled type and operated the presses to print copies on paper which had been manufactured elsewhere by other workers. Then each copy had to be bound by a binder (whether as part of a magazine or as a book on its own) before being distributed by carriers to a retailer who would sell it to a customer.

So, whilst reading Confessions might feel like entering into an intimate conversation with its author, De Quincey and his readers stood at either end of a long chain of people making a living out of the book trade.

More about Confessions of an English Opium Eater

Circulation wars: See the magazine where Confessions was first published.

Make your own confession: Go on an adventure with Confessions of an English Opium Eater as you confess yourself and explore De Quincey’s Edinburgh.

The Secret Life of Books: Find out more about the other books in the series.

Rate and Review

Rate this video

Review this video

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Video reviews