Reading 1 Mary Boatwright, Hadrian and the City of Rome

Source: Boatwright, M.T. (1987) Hadrian and the City of Rome, Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, pp. 119–33.

The Forum Romanum

[…] [p. 119] to the east of the Forum Hadrian erected a building of a still larger size: the Temple of Venus and Roma. According to a strange and improbable story related by Dio Cassius (69.4.4), Hadrian, whose ideas about architecture Apollodorus had made light of during Trajan’s reign, later sent the architect his plans for the Temple of Venus and Roma, asking Apollodorus’ opinion of them. The architect replied that it ought to have been set high and hollowed out underneath so that the building might be more conspicuous from the Sacra Via and so its substructures might accommodate the machines for the Flavian Amphitheater; furthermore, he said, the cult statues were too tall for the building. Thereupon Hadrian became incensed “because he had fallen into a mistake that could not be righted” and had Apollodorus put to death.Footnote 71

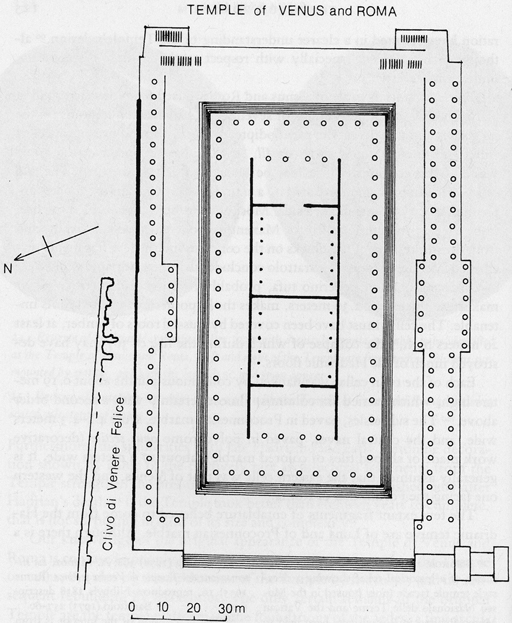

Although the story is well known and often repeated, it is immediately puzzling because the aedes even in ruin does dominate the Sacra Via, and its substructures toward the Colosseum do contain chambers.Footnote 72 The Temple [p. 120] stood inside a precinct supported on a large platform extending from the Summa Sacra Via almost to the Flavian Amphitheater (145 by 100 meters: about 500 by 300 Roman feet).Footnote 73 Dio’s anecdote thus refers to the two areas bridged by the sacred area. This topographical information, however, is incidental to the anecdote, for the main thrust of Apollodorus’ criticism (if true) was directed against the unusually Greek appearance of the Temple. The criticism of the statues’ size suggests that Hadrian was working with the proportions of classical Greece, where the cult statues were always enormous in relationship to their cellae. The temple plan also deviated from conventional Roman temples in being amphiprostyle, facing in both directions within a peripteral colonnade, and being raised on all four sides on a continuous crepis of seven steps (including the stylobate) instead of on a podium.Footnote 74

More topographical information about the Temple comes from the reports that it was built over the Vestibule of Nero’s Golden House, and that the Colossus of Nero was moved to accommodate it (HA, Hadr. 19.12; cf. Pliny NH 34.45). Nero’s rehandling of the Summa Sacra Via and the Velia after the fire of 64 had changed the course of the republican Sacra Via, and under the Flavians it seems that its course may have been altered again; most important for our purposes is that after Nero the branch of the road now called the Clivo di Venere Felice ran south of a structure cut into the slope of the Velia.Footnote 75 The excavations for the Via dei Fori Imperiali exposed the back of the Neronian construction, whose south side is about 8 meters outside and parallel to the western half of the north flank of the Temple of Venus and Roma (see Ills. 19 and 26). The Neronian terrace wall seems to have been part of the work for the Vestibule of the Golden House.Footnote 76

Hadrian extended the platform east toward the Flavian Amphitheater, first laying down a thick bed of concrete (opus caementicium).Footnote 77 The few Hadrianic brick stamps that come from the Temple of Venus and Roma are from drains to the north and west of this platform, and from the southwest side of the platform; all date to 123, except one from the vicinity of the Arch of Titus that dates to 134.Footnote 78 In addition to the foundations of Nero’s Vestibule, the [p. 121] Hadrianic platform incorporates remains of houses of late republican date and an interesting octagonal room, formed by the intersection of two corridors and associated with Nero’s Domus Transitoria.Footnote 79 Thus, although the Temple of Venus and Roma made use of an existing artificial platform, it extended the platform to possibly twice its original length. A natural slope from the Arch of Titus to the Flavian Amphitheater makes the top of the platform’s eastern edge stand almost 8 meters above the platea between it and the Amphitheater; to the west, where the slope toward the Forum Romanum was gentler, the top of the platform was only 2.50 meters above the paving of the Sacra Via.Footnote 80

The date of the Temple of Venus and Roma is problematic. Bloch emphasizes how little brick stamps contribute to dating the monument; few have been recorded, and most of these come from drains.Footnote 81 The earliest stamps, however, provide a terminus post quem of 123, and a likely date of 125–126 for the beginning of construction. These dates can be reconciled with the literary and numismatic evidence, which suggests that the precinct was consecrated in 121, and a date early in the Hadrianic principate for the Temple is implied by the story about Apollodorus.

In the Deipnosophistae, Athenaeus remarks on the joyful and crowded celebrations of the Parilia, called “Romaia” after it was made a festival of the Fortuna of the City of Rome when the “wisest ruler,” Hadrian, consecrated the Temple to the City (8.361 f).Footnote 82 Athenaeus repeats twice in the passage that all who lived or happened to be in Rome took part in the festivities every year. The traditional date of the Parilia was 21 April, and from a series of Hadrianic coins we know the year of the festival’s transformation. Aurei and sestertii, with obverses showing a bust of Hadrian, laureate, and the legend imp caes hadrianus aug cos iii or imp caesar traianus hadrianus aug p m tr p cos iii, have reverses depicting the Genius of Circus, seated by the triple metae (turning posts) of the Circus and holding a wheel, with the legend ann(is) dccclxxiiii nat(ali) urb(is) p(arilibus) cir(censes) con(stituti).Footnote 83 The Varronian date of the coins’ legend is a.d. 121.

[p. 122] In this same year, on the evidence of its obverse legend and the portrait of Hadrian, an issue of aurei showed on its reverse the legend saec(ulum) aur(eum) p m tr p cos iii and a representation of Aion, the embodiment of the golden age: a youth half draped in an oval frame, the zodiac circle in his right hand and a ball mounted with a phoenix in his left.Footnote 84 Since 121 does not coincide with either cycle of Roman secular games, Gagé, Beaujeu, and others have associated this proclamation of a new golden age with the transformation of the Parilia into the Romaia, the Natalis Urbis Romae, and with the consecration of the Temple of Venus and Roma.Footnote 85 This date coincides with Hadrian’s restoration of the pomerium, another link with Rome’s origins.Footnote 86 The brick stamps imply that the actual construction of the Temple was begun only five years after the dedication of the precinct.

This date for the Temple’s consecration, however, has been called into question primarily by R. Turcan and M. Grant. Different coins struck during Severus Alexander’s seventh year of tribunician power, 10 December 227 to 9 December 228, show Roma Aeterna, a seated statue of Roma, Roma and Romulus, or the emperor sacrificing before the Temple of Venus and Roma. The issues have been thought to mark the hundredth anniversary of the Temple’s consecration.Footnote 87 But the Temple and Roma Aeterna appear with increasing frequency on imperial coinage beginning in the time of Septimius Severus,Footnote 88 and so the coins of Severus Alexander seem meant to emphasize the primacy of Rome and a return to religious respect for national traditions, after the sacrileges of Elagabalus, rather than the anniversary of the Temple’s [p. 123] dedication.Footnote 89 There is no real reason to suppose that the Temple was consecrated in 128; 121 is preferable.

The date of the Temple’s completion is also problematic. The chronicles give relatively late dates for it: Cassiodorus writes under the year 135 Templum Romae et Veneris sub Hadriano in urbe factum (under Hadrian the Temple of Roma and Venus was made in the city [of Rome]: Mommsen, Chron. Min. ii, p. 142), and the same is repeated by Jerome for 131 (Jerome, Chron. p. 200 h.). Jerome’s date is unlikely, as Hadrian was out of Rome that year,Footnote 90 and even Cassiodorus’ seems too early, given the brick stamp of 134 found in the Temple’s substructures near the Arch of Titus.

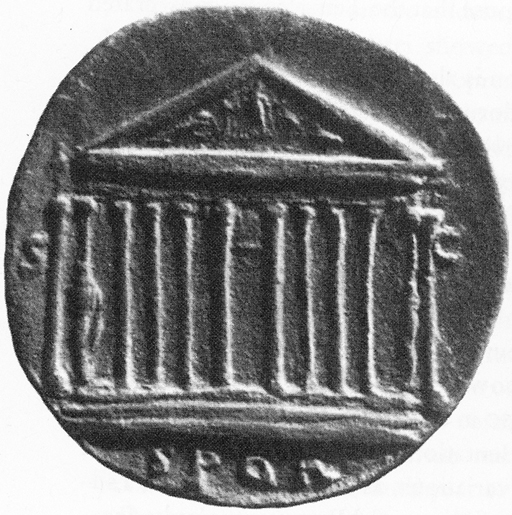

Again, however, the numismatic evidence is of help. Hadrianic sestertii and medallions, all datable after 132, show on the reverse a decastyle temple, unidentified but usually with sc or ex sc in the field and spqr in the exergue (see Ill. 24). The variations in the representation are numerous: D. F. Brown has identified two main types with six variations, as well as a variant on a silver medallion.Footnote 91 But since the Temple of Venus and Roma is the only decastyle temple reliably attested to in Rome, and coins struck under Antoninus Pius from 141 to 143 represent a similar decastyle temple and carry in addition the explanatory legend romae aeternae or veneri felici (see Ill. 25), the identification of the temple on the Hadrianic coins as the Temple of Venus and Roma seems all but certain.Footnote 92 As we shall see below, the types of the cult images that were eventually housed in the temple appear on late Hadrianic coins, but it is only on Antonine coins that we find identifiable cult images represented in the cella of the temple.Footnote 93 It therefore seems likely that the Temple was actually completed in every detail only under Antoninus Pius,Footnote 94 which will also account for the late brick stamp found in situ in the substructures.

[p. 124] Furthermore, the similarities with late Hadrianic and early Antonine decoration shown by some of the relatively rare architectural fragments from the Temple strengthen the presumption that the Temple was finished only after Hadrian’s death.Footnote 95 If the Temple took better than eighteen years to complete, that is not surprising in light of its size and complexity.

Our knowledge of the original appearance of the Temple of Venus and Roma is confused not only by the variations in representations of the Temple on coins, but also by the destruction of the Temple by fire in 307 and its subsequent rebuilding by Maxentius. The only certain remains of the original Temple are the temple platform, some foundations of the aedes, a few architectural fragments, and parts of the lateral porticoes of gray granite columns that framed the long sides of the precinct. Barattolo’s recent investigations of the extant remains; of the plans, elevations, and sketches of the Temple made in the early nineteenth century; and of photographs and plans taken at the beginning of the twentieth century both before and during the Temple’s restoration [p. 125] have resulted in a clearer understanding of the Temple’s design,Footnote 96 although many details, especially with respect to the Temple’s decoration, must remain elusive.

The Hadrianic Temple of Venus and Roma, raised from the surrounding platform on a continuous crepis of seven steps, had twenty columns on the long sides and was decastyle, pseudodipteral, and with an interior pronaos at either end tetrasyle in antis.Footnote 97 (see Ill. 26). The base diameter of the fluted white marble columns (which may be Maxentian) is 1.87 meters.Footnote 98 The two cellae, back to back and separated by a straight wall, were almost square, approximately 25.70 meters on a side. Most of the cella walls survived the fire, to be used as an exterior shell for Maxentius’ concrete apses and walls, and from the impression of the blocks on the concrete and the few fragments that escaped later depredations, Barattolo concludes that the Hadrianic walls were in ashlar masonry of peperino tufa, probably revetted with marble. Their maximum thickness, 2.30 meters, makes the hypothesis of vaulted roofs untenable. The cellae must have been covered by trussed roofs of timber, at least 26 meters high,Footnote 99 the collapse of which during the fire of 307 may have destroyed much of the Hadrianic floors.

Each of the twin cellae was flanked by continuous plinths about 0.19 metres high, which carried six columns, almost certainly with a second order above.Footnote 100 The side aisles, paved in Proconnesian marble, were 4.2–4.3 meters wide, and the central naves, paved in polychrome opus sectile (decorative work made of shaped tiles of colored marble), about 17.2 metres wide. It is generally assumed that the eastern cella was that of Venus, and the western one facing the Forum that of Roma.Footnote 101

The few extant fragments of entablature believed to come from the Hadrianic temple are of Luna and of Proconnesian marble. Although there is a [p. 127] marked Pergamene character in some parts that strongly resemble the decoration of the Hadrianic Traianeum at Pergamum, Leon has pointed out other more Roman elements and suggests that two teams of carvers – one using more eastern forms and the other, more Roman ones – worked on the Temple’s decoration.Footnote 102

Although the aedes was set axially on its basement platform, 19 meters from either long side, the flanks of the temenos were not treated alike. To the north, where the platform fell short of the high Neronian terracing that was cut into the slope of the Esquiline, the lateral porticus (5.90 meters deep) was closed behind by a wall, a single row of gray granite columns with white marble Corinthian capitals responding to pilasters on the back wall. The distance from this portico to the aedes was 13.00 meters. On the south, where the platform ran along the Sacra Via from the Arch of Titus to the platea around the Meta Sudans, the portico, on a wider foundation (7.60 meters), had two rows of gray granite columns and was probably an open colonnade of Corinthian order. Here the portico was only 11.00 meters distant from the aedes. All the columns in both colonnades seem to have been four Roman feet (1.18 meters) in base diameter.Footnote 103

A pavilion of five bays resembling a propylaeum and projecting a little from the lateral porticoes interrupts each at the middle. Since these were not true passageways, their purpose seems to have been simply ornamental, to mask the disparity of the two spaces flanking the aedes.Footnote 104 Their columns seems to have been cipollino, a striking change of color.Footnote 105

Less is known about the treatment of the east and west ends of the temenos. A wide staircase on the west running nearly the full width of the platform seems to have had no colonnade across it, and no evidence has been [p. 128] found for a colonnade on the east where the platform rose almost eight meters above the platea below. We can safely assume that there was a fence or balustrade here.Footnote 106 At the platform’s northeast and southeast corners staircases in two flights gave access to the temenos. Between the northeast stair and the Flavian Amphitheater stood the Neronian Colossus which Hadrian had altered to represent Sol. Hadrian is said to have planned to erect a similar colossus of Luna, perhaps symmetrically on the axis of the Temple (cf. HA, Hadr. 19.13). Sol and Luna were symbols of eternity for the Romans.Footnote 107 The cavities visible in the platform’s eastern edge toward the Flavian Amphitheater postdate the Hadrianic construction, and this face of the concrete substructure, like the exposed faces elsewhere, was originally covered with opus quadratum, probably of peperino.Footnote 108

The Temple of Venus and Roma is an architectural anomaly and this fact, taken together with the anecdote of Dio, raises the question of its motivation. The coupling of Venus with Roma must strike us as surprising,Footnote 109 and will be discussed further. The Temple was not only the largest in Rome, but strongly Greek in its general appearance.Footnote 110 Most architectural historians have credited [p. 129] Hadrian with the Temple’s design and conception, and they may well be right. We should note, however, that like other temples in Rome, the new Temple, and therefore the cult it was to house, would have had to be approved by the senate. As evidence of such cooperation, Gagé has pointed to the senatorial duodecimviri urbi Romae, board of twelve men of the City of Rome, associated with the Temple;Footnote 111 this priesthood, however, was created only after the Temple was completed. More direct collaboration is suggested by the double legend on most of the Hadrianic coins depicting the Temple: ex sc, spqr. Strack notes that this twofold legend emphasizes the inclusion of all Rome in the new cult,Footnote 112 an idea echoed a century later in what Athenaeus has to say about the Romaia (Parilia). The cult of Venus and Roma, although new, was calculated to appeal to Rome.

The real innovation of the Hadrianic cult of Venus and Roma was the worship of Roma in Rome itself.Footnote 113 Yet the time was right for it. From the late third and early second centuries b.c. Roma was worshiped in the Greek East as an act of political homage, and the cult had developed significantly after the establishment of the principate, when the worship of the princeps was joined to that of Roma. The double cult of Roma and Augustus spread throughout the east and, to a lesser extent, in the west, and helped promote loyalty and solidarity.Footnote 114

Roma as a divinity made her appearance in Rome relatively late, but she had been represented in the art of the imperial city with increasing frequency. Although Ennius speaks of Roma as a semidivine personification (Scipio 6), it is only in Augustan and Flavian literature that she appears frequently.Footnote 115 [p. 130] Martial, for example attributing the words to Trajan, glorifies the deity (Mart. 12.8.1–2).Footnote 116 Similarly, although the head or figure of Roma begins to appear on Roman coins arguably from soon after the war with Pyrrhus,Footnote 117 representations of Roma on coins become rare after the beginning of the first century b.c. and are resumed only in late Neronian times.Footnote 118

In the major arts in Rome an image of Roma was shown on the hand of Jupiter Capitolinus in the restoration of the temple by Q. Lutatius Catulus in 78 b.c. (Dio Cass. 45.2.3), but her appearance becomes common only after the Julio-Claudian period. Well-known representations of Roma on state reliefs are found on the Ara Pacis, the Cancelleria reliefs, the Arch of Titus, and the great Trajanic frieze now incorporated into the Arch of Constantine.Footnote 119 The creation in Rome of a cult for the goddess Roma was anticipated by the ever more insistent representation of her, and prior to Hadrian Roma appeared in imperial art and literature most closely associated with Augustus, the three emperors of 69, and the Flavians. She was an easily intelligible claim of legitimacy for a Roman princeps.

The Hadrianic cult of Roma transcended specific ties: the representations of the cult statue on coins carry the legend romae aeternae or roma aeterna,Footnote 120 and this concept is extended by the transformation of the Parilia into the Romaia, celebrating the birthday of the city, and association of the festival with the Temple on the Velia. The location of the new Temple near the early shrines of the Penates, the Lares, and others linked to Rome’s foundation and formation reinforced the concept of a renewal of eternal Rome, a concept additionally expressed in other late Hadrianic issues with romulo conditori.Footnote 121 The coins of romae aeternae are matched by contemporaneous (a.d. 138) issues in gold and silver depicting Venus Felix, the other deity worshipped in the double Temple.Footnote 122 Here we can see even more clearly the universal appeal of the new cult in Rome.

[p. 131] Venus had long been venerated in Rome under many guises.Footnote 123 She had begun to have shrines and temples in Rome by the early third century b.c., but towards the end of the republic she became especially the patroness of triumphatores, because she was thought to confer military success. Sulla ascribed his rise to power to Venus, and Pompey dedicated the temple that crowned his theater to Venus Victrix. The cult of Venus Genetrix went farther and made her ancestor and protectress of the Roman dictator, the Julian house, and the Roman people.Footnote 124 Despite the Julio-Claudian promotion of Venus as the genetrix Aeneadum (the ancestress of the Romans, the race sprung from Aeneas), during the first century of the principate Venus Genetrix became more of a personal patroness of the emperor than a national one.Footnote 125

The Hadrianic cult of Venus Felix reversed this specialization. Although the Hadrianic epithet Felix is not found used with Venus’ name before Hadrian, it then becomes common in the second century.Footnote 126 It indicates that this Venus is especially a goddess of fecundity and prosperity, and her popular appeal is reflected in the altar erected in the Temple’s precinct in 176, on which all newly married couples were to offer sacrifice (Dio Cass. 71.31.1).

The Hadrianic coins depicting the statues of Venus Felix and Roma Acterna show an interesting similarity between these divinities. Venus Felix sits in a high-backed throne facing left, wearing a long robe and a diadem; in her raised left hand she holds a spear and in her outstretched right, a winged Amor. The type is new. Roma sits, like Venus, but on a curule chair; she wears a long robe and a helmet. In her raised left hand she holds a spear and in her right, the Palladium, the symbol of the eternal city, a Victoria, or the sun and the moon. The issues date to 138. On analogy with the veneris felicis legend the inscription romae aeternae must be constructed as genitive, thus [p. 132] marking the images as those belonging to the Temple then under way.Footnote 127 The two seated statues, back to back in the Temple, expressed complementary concepts: Rome’s perennial might rests on the Roman people.

Hadrian’s new Temple (and cult) of Venus and Roma was more national than dynastic, breaking precedent with earlier imperial temples in and around the Forum by exalting the strength and origins of Rome and the Roman people above those of an individual family. The Temple’s enormous foundation runs alongside the Arch of Titus and the upper portion of the Sacred Way, thus stressing the association of Roman triumphs with the divine origins of Rome and with the very strength of the city. The substructures incorporated the remains of Nero’s Vestibule and other domiciles of Roman dynasts, and the relocation and transfiguration of Nero’s colossal statue manifested the reappropriation of the area as public. Kienast has justly said that the monumental whole towered over the buildings of the Roman Forum below it, superseding the earlier limits of the areas established by the Temple of the Deified Julius; it documented that for Hadrian, Rome was materially and ideally the center of the Roman world, and substantiated Hadrian’s claims to be a new founder of the city, another “Romulus Conditor.”Footnote 128 Yet the Temple of Venus and Roma also marks a broader conception of Rome.

The new national temple epitomizes the Roman empire of Hadrian’s day. It was unmistakably Greek in general appearance: F. E. Brown has called it “a Greek mass set in a Roman space,” and notes the analogy of its site across from the Capitoline to that of Athen’s Olympieion, which Hadrian finally completed across from the Acropolis.Footnote 129 Barattolo goes a step farther and believes that this Greek temple in Rome advertised Hadrian’s hopes of a new panhellenism.Footnote 130 Despite the Greek appearance of Hadrian’s Temple of Venus and Roma, however, it is important to recall that the building was begun by a princeps with a Spanish background, and its appeal was to Romans at home. It was linked to some of the earliest shrines of Rome, and to a new annual celebration of Rome’s founding date. The Hadrianic Temple of Venus and Roma was to unite all Romans in a new state cult that reflected their glory and [p. 133] their origins, much as Hadrian’s Olympieion and Panhellenion served to unite the Greek East.Footnote 131 The new concept and cult were extremely popular, although the cult of Roma seems to have eclipsed that of Venus by the third century. Gagé has shown that the Temple and the worship of Roma were among the longest-lived survivors of pagan Rome, significant even for Christians of the fifth century.Footnote 132 The associated festival of the Natalis Urbis Romae was also famous and durable, and had constant official favor: the Feriale Duranum records it celebration by the army in the early third century in Dura Europus out on the banks of the Euphrates.Footnote 133

With Greek architectural ambiguity reinforced by the double apses back to back, Hadrian’s Temple looked both to the ancestral center of the city and out to the larger Roman world. Its physical mass did indeed dominate the Forum below, but this mass, strategically located, extolled Rome’s traditions rather than an individual dynasty. Similarly, Hadrian’s additions to the Palatine residences were oriented in accordance to the major buildings of the Forum below them. Through his work at and near the Forum Romanum, Hadrian evinced imperial submission to the state rather than imperial domination of the Roman people; his constructions reiterated the public claims he made at the beginning of his principate: that he would govern the state so that all would know it belonged to the people, not to him alone (populi rem esse, non propriam: HA, Hadr. 8.3). These constructions reflect the harmony that must have characterized the middle years of Hadrian’s principate, when there were no provincial or foreign disturbances, the government was running smoothly, and all Romans could unite in celebrating Hadrian’s assumption of the title Pater Patriae in 128.Footnote 134

Footnotes

- 71 MacDonald, ARE 131–37, discusses this anecdote and its historicity.Back to main text

- 72 MacDonald, ARE 136, suggest that Hadrian modified his original plans to accord with Apollodorus’ criticisms. Gullini, “Adriano” 73–74, also speculates on Apollodorus’ criticisms. This account of Apollodorus’ death is not trustworthy: see above, Introduction, n. 30 [not reproduced here]. For the chambers, which are post-Hadrianic, see below, n. 108.Back to main text

- 73 Barattolo (1978) 399 n. 12; Coarelli, Roma (1980) 95.Back to main text

- 74 Barattolo (1978) 399, also gives further refinements of the “Greek” plan.Back to main text

- 75 For the complicated modifications of the Sacra Via, see Coarelli, ForArc 42–43.Back to main text

- 76 A. M. Colini, “Considerazioni su la Velia da Nerone in poi,” in Città e architettura 129–45, with earlier bibliography, including his “Compitum Acili,” BullComm 78 (1961–62) [1964] 148–50. For the topography of the Golden House in this area, see n. 36 above [not reproduced here].Back to main text

- 77 Lugli, Edilizia II, pl. c, 2, for the concrete with aggregate of travertine and lava caementa; Blake/Bishop, 40. The concrete is not homogeneous: in some places it includes brick, in others, tufa and harder materals.Back to main text

- 78 Bloch, Bolli 250–53.Back to main text

- 79 See, e.g., the original report by M. Barosso, “Le construzioni sottostanti la Basilica massenziana e Velia,” in Atti del 5° congresso di studi romani, ii (Rome 1940) 58–62, plates xii–xv. See also Crema, 267 and figs. 306, 307; and MacDonald, ARE 21–23.Back to main text

- 80 Barattolo (1978) 399, gives these figures as 9 and 2.70 meters, respectively; my figures are based on the earlier ones in V. Reina et al., Media pars urbis (Roma 1910) fol. 6.Back to main text

- 81 Bloch, Bolli 252–53.Back to main text

- 82 For the interpretation “consecrate” [the ground and foundations] rather than “build”: R. Turcan, “La ‘Fondation’ du Temple de Venus et de Roma,” Latomus 23 (1964) 44–48.Back to main text

- 83 BMC, Emp. iii, p. 282, no. 333, pl. 53.5; pp. 422–23, nos. 1242–43: the sestertii carry an additional sc in the exergue of the reverse. See, too, Hill, D&A 54; and Strack, Hadrian 102–105, who notes other possible completions for P.Back to main text

- 84 Strack, Hadrian 100–102, pl. 1.78; BMC, Emp. iii, p. 278, no. 312, pl. 52.10; Beaujeu, 153; Gagé, “Templum urbis” 176–80.Back to main text

- 85 Beaujeu, 131–32; Gagé, Jeux Séculaires 94–97. Hadrian’s interest in the “true” chronology of the secular games may have come only later: cf. Phlegon’s peri makrobion 37.5.2–4 (of ca. a.d. 137), reproduced in G. B. Pighi, De ludis saecularibus populi Romani Quiritium, libri sex, 2nd ed. (Amsterdam 1965) 56–58.Back to main text

- 86 A medallion of 121 that represents the sow and her piglets must be another allusion to Rome’s origins: Strack, Hadrian 104; and J.M.C. Toynbee, Roman Medallions (New York 1944) 143. Strack also dates to 121 the issue of Hadrian as romulus conditor, although it is actually much later (cf. BMC, Emp. III, p. cxli). The year 121 also marked the fifth anniversary of Hadrian’s accession; for the increasing importance in the second century of such milestones, see J.W.E. Pearce, “The Vota Legends on the Roman Coinage,” NC, ser. 5, 17 (1937) 117; and M. Grant, Roman Anniversary Issues (Cambridge 1950) 98–99.Back to main text

- 87 Turcan, “Temple de Venus et de Rome” 43; Grant, Anniversary 126–28. Turcan then supposes a double consecration, a consecration (inauguratio) of the ground in 121, and the foundation proper in 128; Leon Bauornamentik 213 n. 10, seems to accept only the date of 128. See also Toynbee, Roman Meallions 103.Back to main text

- 88 The vast majority of the 200 different issues showing Venus and Roma were struck from Septimius Severus on; D. F. Brown, “Architectura Numismatica” (Ph.D. diss., New York University 1941) 223–48, 334; Gagé, “Templum urbis” 158–69.Back to main text

- 89 Cf. Gagé, “Templum urbis” 159.Back to main text

- 90 Cf., e.g., Strong, “Late Ornament” 122 n. 21.Back to main text

- 91 Brown, “Architectura Numismatica” 223–25; Pensa, “Adriano” 51–59; Hill, D&A 76. For the coins see: BMC, Emp. iii. p. 467, no. 1490, pl. 87.6; p. 476, no. 1554, pl. 89.5 and n. 1554; Gnecchi, III, p. 19, no. 88; RIC II, p. 440, nos. 783–84; Magnaguti, iii, p. 81, no. 501, pl. 16, and p. 73, no. 43; Mazzini, II, p. 150, nos. 1421–22, pl. 52, and p. 96, no. 593, pl. 34.Back to main text

- 92 romae aeternae: BMC, Emp. iv, pp. 205–206, nos. 1279–85, pls. 29.10–13, 30.1–3; veneri felici: BMC, Emp. iv, pp. 211–12, nos. 1322–25, pls. 31.3, 31.8–9.Back to main text

- 93 BMC, Emp. iv, p. 206, nos. 1284–85, pls. 29.12, 30.1; cf. Strack, Hadrian 176–77. Other Antonine coins show no statue within the Temple (e.g., BMC, Emp. iv, p. 205, nos. 1279–80, pls. 29.10–11, and p. 206, no. 1282, pl. 40.1); or an indistinguishable form (e.g., BMC, Emp. iv, pp. 205–206, nos. 1281, 1283, pls. 29.13, 30.3; Mazzini, ii, no. 699).Back to main text

- 94 Many scholars propose that it was dedicated in the period 135 to 137, but accept that the work was completed only under Antoninus Pius: e.g., Blake/Bishop, 41; Bloch, Bolli 252 n. 192; Mattingly, BMC Emp. iv, p. lxxxii; Platner-Ashby, s.v. Venus et Roma, Templum, 553; and Strack, Hadrian 174–76, but see idem, iii.69.Back to main text

- 95 Strong, “Late Ornament,” esp. 122, 127–29.Back to main text

- 96 Barattolo (1973), 247–48. Two fragments of a historical relief showing a decastyle temple façade (now housed in the Museo Nazionale delle Terme and the Vatican Museo Paolino in Rome) have been held to depict the façade of Venus and Roma (e.g., Platner-Ashby, s.v. Venus et Roma, Templum, 554), but the relief is more likely Julio-Claudian and antedates the Temple: Koeppel, “Official State Reliefs” 488E. Pensa, “Adriano” 55, dates the relief as Trajanic.Back to main text

- 97 This description is based on that of Barattolo (1973) 245–69, except where noted.Back to main text

- 98 Barattolo (1978) 398; A. Muñoz, La sistemazione del Tempio di Venere e Roma (Rome 1935) 16, reproduces Nibby’s 1838 description.Back to main text

- 99 Barattolo (1973) 257–60.Back to main text

- 100 The description of the interior is from Barattolo (1974–75), except where noted. The porphyry columns now visible in the interior belong to the Maxentian rebuilding (A. Muñoz, Via dei Monti e Via del Mare [Rome 1932] 17).Back to main text

- 101 Gagé “Templum Urbis” 155 n. 4. Though he cites no evidence, subsequent scholars concur.Back to main text

- 102 Leon, Bauornamentik 224, 231; and see Strong, “Late Ornament” 127–29, 136–38.Back to main text

- 103 Barattolo (1978) 400 nn. 15, 16, gives these measurements and description, correcting the commonly accepted symmetrical plan; cf. Blake/Bishop, 40. For the size of the columns, see Nibby, in Muñoz, Sistemazione 14. The earlier topography of the north side can be deduced from the imprints of the wooden scaffolding for the concrete foundation, and from the prints of the blocks of opus quadratum at the northeast extremity. Pensa, “Adriano” 56–57, conjectures that the two isolated columns to either side of the temple depicted on some Hadrianic coin issues (e.g., BMC, Emp. iii, p. 467, no. 1490, pl. 87.6) symbolize these lateral colonnades.Back to main text

- 104 Barattolo (1978) 400 n. 16. Blake/Bishop, 41, less persuasively hold that the blind propylaea were to break the “monotony” of the long porticoes of gray granite columns.Back to main text

- 105 In addition to the cipollino fragments visible in the temenos, another similar fragment was found in a propylon area during the excavations in the 1930s: Muñoz, Sistermazione 20.Back to main text

- 106 Blake/Bishop, 41, note that a colonnade on the east side would have obstructed the view to and from the amphitheater.Back to main text

- 107 According to Hadrian’s biography, the statue of Luna was to be made with Apollodorus’ aid. The Chronicon Paschale dates the removal of the Colossus to 130, which can be adjusted to 128: cf. Howell, “Colossus” 297. See also Gagé, “Colosse et fortune de Rome” 110–16; Strack, Hadrian 177; and Pensa, “Adriano” 56, for the associations with eternity.Back to main text

- 108 Personal inspection convinces me that the cavities were cut into the structure only later; see, too, Blake/Bishop, 40–41. The two scholars also conjecture, but without evidence, that marble revetted the north side, and that the two ramp staircase on the east were of marble steps. Instead, the relatively numerous blocks and fragments of peperion tufa found in the area indicate that peperino was used (cf. Barattolo [1973] 249), and on analogy to the fire walls of the Fora of Augustus and of Trajan, this would not have been covered.Back to main text

- 109 Until the time of Hadrian, it was very rare, although Venus and Roma had appeared together earlier on an issue struck in 75 b.c. by the moneyer C. Egnatius Cn. f. Cn. n. Maxsumus, in what seems to be popularis propaganda: M. H. Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage, i and ii (London and New York 1974) 405–406, #391/3. Here, however, the two deities were represented standing side by side, with a rudder on top of a prow to either side of them. See below for the Hadrianic representations.Back to main text

- 110 Barattolo (1978) 397–99, stressing the Greek derivation of the Temple explains its few deviations from the canons of Hermogenes of Alabanda for pseudodipteral temples. For dipteral and pseudodipteral temples in Rome, see Gros, Aurea Templa 115–22. Barattolo (1978) 402–403, lists the four Greek temples named by Pausanias that may have influenced the plan of Venus and Roma (at Sicyon, Argos, Olympia, and Mantineia). Snidjer, “Tempel der Venus und Roma” 3–4, mentions only the temples at Argos and Mantineia. Barattolo, (1978) 407, stresses the similarity of Venus and Roma to the Temple of Artemis Leukophryene at Magnesia on the Meander. See also n. 102 above.Back to main text

- 111 Gagé, “Templum urbis” 158–59. Gagé later doubted that this priestly board dealt with the Temple: “Sollemne urbis” 227.Back to main text

- 112 Strack Hadrian 175, who also takes the legend to exclude Hadrian’s responsibility for the Temple, noting that HA, Hadr. does not include the Temple among Hadrian’s works. Yet given the vast number of Hadrianic works omitted from the biography, this last argument cannot hold. Cf. Snidjer, “Tempel der Venus und Roma” I, 7: and Gagé, “Templum urbis” 154–55.Back to main text

- 113 For example, Beaujeu, 133–36. Wissowa, ReKu, 2nd ed., 340–41, suggests that the worship of the Dea Roma (whom he considers the divine symbol of the city) reveals the growing importance of the city itself to provincials and Roman citizens in the provinces. Beaujeu sees the new cult as part of Hadrian’s policy of the provincialization of Rome; cf. Gagé, “Sollemne urbis” 227.Back to main text

- 114 See, esp., R. Mellor, “Thea Rhome.” The Worship of the Goddess Roma in the Greek World (Göttingen 1975) 13–26; idem, “The Goddess Roma,” ANRW II.17.2 (1981) 956–72; and C. Fayer, Il culto della Dea Roma. Origine e diffusione nell’Impero (Pescara 1976) 9–28.Back to main text

- 115 C. Koch, “Roma Aeterna,” Gymnasium 59 (1952) 128–43, 196–209; U. Knoche, “Die augusteische Ausprägung der Dea Roma,” Gymnasium 59 (1952) 324–49; Mellor, “Goddess Roma” 1004–1010.Back to main text

- 116 Mellor, “Goddess Roma” 1010.Back to main text

- 117 Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage 721–25, with bibliography; contra, Mellor, “Goddess Roma” 974–75.Back to main text

- 118 C. C. Vermeule, The Goddess of Roma in the Art of the Roman Empire (Cambridge, Mass. 1959) 29–42.Back to main text

- 119 Vermeule, Goddess Roma 83–114, has many examples; for a different interpretation of some of these figures as representations of Virtus, see J.M.C. Toynbee, in JRS 36 (1946) 180–81.Back to main text

- 120 romae aeternae: BMC, Emp. III, p. 329, no. 707, pl. 60.20 = Smallwood, #380a (denarius); roma aeterna: BMC, Emp. III, pp. 328–29, nos. 700–703, pl. 60.17–18 (aurei); roma aeterna sc: BMC, Emp. III, p. 474, no. 1541, pl. 88.12 (sestertius).Back to main text

- 121 Dated to 138 by Hill, D&A 69; to 137 by Mattingly, BMC, Emp. iii, p. cxli; and above, n. 86, for the coins.Back to main text

- 122 BMC, Emp. iii, p. 334, nos. 750–56, pl. 61, 15–16, cf. Smallwood, #380b: R. Pera, “Venere sulle monete da Vespasiano agli Antonini: aspetti storicoo-politici,” RIN 80 (1978) 84–88. For the date of both sestertii and aurei: Hill, D&A 69–70.Back to main text

- 123 See, e.g., Beaujeu, 136; and R. Schilling, La religion romaine de Vénus depuis les origins jusqu/au temps d’Auguste, 2nd ed. (Paris 1982) 62–266.Back to main text

- 124 Beaujeu, 137; Schilling, Religion de Vénus 272–324; C. Koch, “Venus,” RE 8 a.i. (1955) 858–68; idem, “Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der römischen Venus-Verchrung,” Hermes 83 (1955) 35–48; and (for Sulla) Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage 373, on nos. 359/1 and 2.Back to main text

- 125 See, e.g., Koch, “Venus-Verchrung” 47–50.Back to main text

- 126 Koch, “Venus” 871; and idem, “Venus-Verchrung” 48–49. In 138 Hadrian also struck aurei and a medallion labeled veneri genetrici (BMC, Emp. iii, pp. 307, 334, 360, 538, nos. 529, *, 944–49, 1883–84, pls. 57.12, 69.19–20, 99.4), and denarii slightly earlier, with roma felix (BMC Emp. iii, p. 329, nos. 704–706, pl. 60.19), or roma felix cos iii p p (BMC, Emp. iii, p. 343, nos. 566–69, pl. 58.11); cf. Hill, D&A 69: and Strack, Hadrian 177–80. Hadrian’s new cult on the Velia united all these aspects.Back to main text

- 127 Strack, Hadrian 176–77. The similar images marked roma aeterna (see n. 120 above) must also be representations of the cult statue. Vermeule, Goddess Roma 35–38, discusses Roma Aeterna. This scholar rather implausibly concludes from the variants in the numismatic depictions of the cult statue that the attribute in its right hand was detachable. Toynbee, Hadrianic School 135–37, remarks on the novelty in Roman art of Roma’s long chiton, which associates the representation closely with the Greek Athena type.Back to main text

- 128 Kienast, “Baupolitik” 402–407, citing the coins mentioned in n. 86 above.Back to main text

- 129 F. E. Brown, “Hadrianic Architecture” 56.Back to main text

- 130 Barattolo (1978) 410.Back to main text

- 131 Olympieion and Panhellion: A. S. Benjamin, “The Altars of Hadrian in Athens and Hadrian’s Panhellenic Program,” Hesperia 32 (1963) 57–86.Back to main text

- 132 Beaujeu, 113, 161; Gagé, “Sollemne urbis” 225–41; idem, “Templum urbis” 169–72. Wissowa, ReKu, 2nd ed., 340 n. 6, notes Maxentius’ dedication of a base on 21 April 308: Marti invicto patri et aeternae urbis suae conditoribus [To the invincible Father Mars and the founders of his eternal city] (CIL 6.33856).Back to main text

- 133 R O. Fink, A.S. Hoey, and W.F. Snyder, “The Feriale Duranum,” YCS 7 (1940) 102–12, who argue, however, that the cult of Urbs Roma Aeterna was not very popular in the provinces, particularly no in the Greek East.Back to main text

- 134 For the date: Jerome, Chron. p. 199h.; L. Perret, La Titulature impériale d’Hadrien (Paris 1929) 62–73, suggests that Hadrian assumed the title on 21 April 128, on the occasion of the Natalis Urbis; Weber, 200 n. 710, on 11 August 128, on the dies natalis imperii. The earlier date suggested by W. Eck, “Vibia(?) Sabina, No. 72b,” RE, Suppl. 15 (1978) 910, does not affect my argument. Garzetti, 395, notes the frequency of the legend concordia on the first coins struck after 128.Back to main text