If you try to picture what life would have been like in 1500, in the place we call “Britain”, you might come up with a very different image from how things are now. You might think of a smaller population, mostly living and working in rural communities, in harmony with the seasons.

Move forward to 2000, and the image changes profoundly. You might picture towns and cities full of people, with a myriad of new technologies coming before your eyes.

How this transformation happened is one of the great questions of historical study, and not just for academics; whether you’re interested in the environment, social issues, or the sources of prosperity, the history of how economic modernity came to be really matters.

Historians have been debating this subject for years, and the literature is vast and diverse. But, to simplify for a moment, one could talk of two schools of thought that seem to go “in” and “out” of fashion.

One is the view that economic modernity emerged in a rush, in a sudden “Industrial Revolution”. Traditionally this is dated from the late eighteenth century, and focuses on the sudden rise of the cotton mills and the increasing use of steam power. The other view is its corrective, looking at ways in which change was more gradual, spanning centuries rather than decades, with one example being the growth of craft industries in homes and workshops, using hand-based technologies.

At times, the historical debate between these two schools of thought has seemed to go around in circles, and one might ask, what could truly move our understanding forward?

William William's A View Of The Iron Bridge - Ironbridge is often lauded as the 'birthplace of the Industrial Revolution'

William William's A View Of The Iron Bridge - Ironbridge is often lauded as the 'birthplace of the Industrial Revolution'

A new perspective

One route is the unearthing of new statistical information. In the 1980s, the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure produced a much-respected study of the growth of population; and their research continues in other related areas, most recently with respect to the changing occupational structure of England.

When would they say that England began to shift away from a predominantly agricultural world, towards employment in manufactures and commerce? It was earlier than one might think. In a chapter by Leigh Shaw-Taylor and Tony Wrigley from 2014, they estimated that, as early as c. 1710, 37.7 per cent of working men and women were already part of the “secondary sector”, which is mostly manufactures, plus a few other areas such as building.

Although some of them would have combined this with farm work, this suggests that the secondary sector had already been growing for many years. The indications are that England was still largely agricultural in early Tudor times; but further estimates in a paper by Shaw-Taylor from 2014 suggest that England’s shift towards manufactures was underway in the late sixteenth century, during the reign of Elizabeth I.

“What, Elizabeth?!” one might say. Up till now this has not often been a starting-point for text books on industrialisation! However, if you dig back into the secondary literature, it is not without precedent.

For example, in the 1970s, Joan Thirsk detailed a late sixteenth century beginning in her Ford Lectures at Oxford, published as Economic Policy and Projects: the Development of a Consumer Society in Early Modern England (1975). Drawing on textual primary sources, she wrote a political and cultural account that might help us to make sense of the Cambridge Group’s recent figures.

Their findings might even re-ignite an old debate, about the economic consequences of the Reformation. The reign of Elizabeth was not long after England’s monasteries were dissolved; and, after the swift changes under Henry, Edward and Mary, it could be seen as the start of a lasting Protestant settlement.

Some eighteenth-century perceptions

What struck me about the new figures on occupational structure was how they fitted in with some of my researches into economic discussion during the eighteenth century. There were writers then who also suggested an Elizabethan start, although they did not have the benefit of the Cambridge Group’s studies of parish records.

One such was the London merchant Joshua Gee, an arch protectionist, advocate of slave plantations, and sometime adviser in government circles. In his Trade and Navigation of Great Britain (1729), he said that little had changed in the economy between the time of William the Conqueror and Elizabeth I, but her reign had been a golden age which saw the start of the nation’s success in manufactures and international trade.

He wrote of how Elizabeth had encouraged foreign artisans to settle in England; she had also “endowed them with many privileges, and enabled them to make a very great progress in carrying on the woollen and other manufactures”.

Regarding the woollen industry, he claimed that “in her time that manufactury was so effectually established, that a mighty progress was made therein, and encreased so considerably, that they gained the reputation of being the best in Europe”.

Later in the century, Adam Smith’s famous work The Wealth of Nations (1776) was a critique of protectionists like Gee, putting forward a philosophy of free trade, and condemning utterly the use of slavery. However, a close reading reveals that, implicitly, one of the few things that Smith and Gee had in common was their chronology of industrial history.

Smith noted that “from the beginning of the reign of Elizabeth... the English legislature has been peculiarly attentive to the interests of commerce and manufactures”, and he added that “commerce and manufactures have accordingly been continually advancing during all this period”. “The cultivation and improvement of the country”, he said, “has, no doubt, been gradually advancing too; but it seems to have followed slowly, and at a distance, the more rapid progress of commerce and manufactures”.

The implication was a shift from agriculture to commerce and manufactures. One searches The Wealth of Nations in vain for an account of a late eighteenth-century economic take-off, although others later saw him as one of the great heralds of the “Industrial Revolution”.

Before this, Adam Anderson, like Gee a member of the London commercial community, had written the lengthy two-volume work The Origin of Commerce (1764). It compiled detailed historical information, rather than coming down clearly on the side of protection or free trade; but it had plenty to say about the long-term rise of manufactures.

While the reign of Elizabeth was not singled out in the same way, there were indications of a seventeenth-century discontinuity. He wrote of “the large strides which we formerly took in the increase of commerce and wealth, more especially from the year 1640”.

He added that since 1688 there had been “a gradual increase of our commerce, wealth, and people”, noting that “our trading cities and manufacturing towns are generally (and most of them greatly) increased in magnitude and splendor”. These advances, he said, had “not been sudden, but gradual, and [were] therefore solid and rational marks of increasing prosperity”.

Survivals of a gradualist perspective

Between the 1780s and the 1840s, a different perception of industrial history emerged, highlighting the sudden rise of the cotton mills and the adoption of Watt’s steam engine. This was the beginning of the idea of an “Industrial Revolution” dating from the late eighteenth century.

However, the awareness of the gradual advance of manufactures did not disappear overnight. Anderson’s work continued to be put out in new editions, and as late as 1805, his material on the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was reproduced with few changes within David MacPherson’s Annals of Commerce. There were also local survivals of the belief in an older industrial heritage, in regions where their manufactures were known to have been long established.

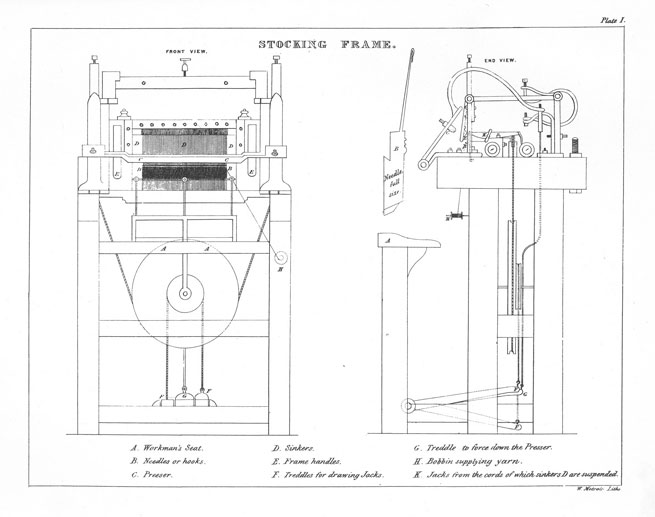

An instance of the latter was a tradition in the East Midlands regarding the framework knitters. If you look at the relevant chapter in John Blackner’s History of Nottingham (1815), or the more extensive coverage in Gravener Henson’s History of the Framework-Knitters (1831) and William Felkin’s A History of the Machine-wrought Hosiery and Lace Manufactures (1867), you can find evidence of a more long-term outlook.

The early technological hero of their accounts was William Lee – the man who had invented the original stocking frame back in 1589, during the reign of Elizabeth. This was seen as the origin of the development of framework knitting since the sixteenth century.

Technical drawing of William Lee's knitting frame from 'A history of the machine-wrought hosiery and lace manufacturers'

Technical drawing of William Lee's knitting frame from 'A history of the machine-wrought hosiery and lace manufacturers'

Conclusion

Does this mean that the “gradualist” historians of economic modernity are right? It is certainly not the whole story, as the Cambridge Group themselves would be quick to point out.

Occupational structure is only one selective way of measuring change; if you use other criteria, different perspectives emerge. Wrigley has long argued that there was a crucial change in the nature of economic development from the late eighteenth century, as England switched from an organic to a mineral-based energy economy with the advance of steam.

It is important to remember the rapid take-off of population growth from the mid eighteenth century; the later changes in working environments as factories replaced work in cottages and workshops; and the swift advance of manufactures in particular localities, even though national aggregate figures were more gradual.

However, to concentrate only on criteria that suggest a later starting-point could also be charged with selectivity. The gradual shift in occupational structure is of real significance, as we try to piece together how our modern world came to be. Seen within the full span of human history – with hundreds of thousands of years as hunter-gatherers, and about ten thousand years of settled agriculture – this shift too might be seen as a “revolution”, even if it took a few centuries!

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews