On 4 August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany. That day, The Daily Mirror reported:

The King and Queen, accompanied by the Prince of Wales and Princess Mary, were hailed with wild, enthusiastic cheers when they appeared at about eight o’clock last night on the balcony of Buckingham Palace, before which a record crowd had assembled.

Seeing the orderliness of the crowd, the police did not attempt to force the people back and went away.

A little later the police passed the word around that silence was necessary as the King was holding a meeting in the Palace, and except for a few spasmodic outbursts there was silence for a time.

Afterwards the cheering was renewed with increased vigour and soon after 11:00pm the King and Queen and Prince of Wales made a further appearance on the balcony and the crown once more sang the National Anthem, following this with hearty clapping and cheering.

Crowds outside Buckingham Palace on 4 August 1914

Crowds outside Buckingham Palace on 4 August 1914

All over Europe, such jubilation occurred as people readied themselves to fight for Kaiser, Tsar or Patrie. This enthusiasm is sometimes referred to as the August experience—a unifying event which allegedly replaced internal divisions and united all people behind the war effort. But this shared enthusiasm is a myth.

On the previous day, The Times described an anti-war meeting held on 2 August, a Sunday, in Trafalgar Square, organised by Socialists and trade unions. The demonstration was disturbed, and seemingly taken over, by patriotic pro-war factions. Among the crowds, so The Times reported, were many poor people, and also foreigners, including German and French, who ‘fortunately’ did not come to blows with each other. The strong anti-Socialist presence on the day appears to have swayed many in the crowd to adopt the enthusiastic mood of the patriots, rather than continuing to oppose the war. But the threat of opposition to war remained.

How the nations tried to unite their people

All Governments recognised the importance of uniting their people behind the war. There was fear of a general strike staged by Socialists on the occasion of a declaration of war, and demonstrations such as the one described in The Times were not uncommon.

In Germany, for example, the Socialist Party’s pacifist stance had been a particular bugbear to the militaristic government, presided over by Kaiser Wilhelm II. Like in London, Berlin (and other German cities) witnessed anti-war demonstrations, and rulers were concerned that instead of concentrating on fighting Germany’s enemies abroad they would first of all have to defeat enemies at home.

A careful case had been made to convince everyone that Germany had been attacked, and this succeeded in bringing the vast majority of the Socialists on board. Rather than launching a strike they voted in favour of war credits in the Reichstag and abandoned their anti-war principles. By making everyone believe that Germany was the victim, the government had achieved unprecedented unity among the people, an indispensable prerequisite for fighting a war.

In France, the President of the Chamber of Deputies had a very similar message for his compatriots. It was feared that as many as 13 per cent of them would not take up arms: ‘There are no more adversaries here, only Frenchmen’, he announced. But despite of this declared holy union (Union sacrée), the French, like their German counter-parts, reacted with mixed emotions to the outbreak of war.

Britons were also convinced that they were going to war for entirely selfless reasons, coming to the defence of Belgium. Pre-war domestic tensions (such as the Irish question and the Suffragettes) were temporarily shelved in the face of a common enemy.

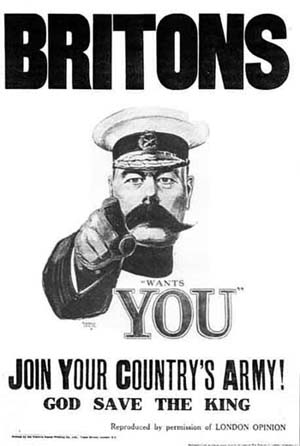

Original Kitchener World War I recruitment poster

Of course, there was a crucial difference between the British army and those from the continent: Britain’s was a volunteer army, not one made up of conscripts, and it could be argued that the huge numbers of volunteers that rushed forward in the first weeks of the war indicate the extent of war enthusiasm in Britain.

Original Kitchener World War I recruitment poster

Of course, there was a crucial difference between the British army and those from the continent: Britain’s was a volunteer army, not one made up of conscripts, and it could be argued that the huge numbers of volunteers that rushed forward in the first weeks of the war indicate the extent of war enthusiasm in Britain.

Between 4 August and 12 September, more than 478,000 men enlisted voluntarily. However, even in the face of such overwhelming numbers we should not assume that everyone really went to war voluntarily and enthusiastically.

Some did, convinced of their duty to fight in a just cause, some went in search of adventure, or simply to escape their lives at home, others because of peer pressure, and because of the general expectation that men would enlist.

Elsewhere, of course, they went because conscription forced them to go, as indeed it also would in Britain once it was introduced in 1916.

In 1914, contemporaries reacted in various ways to the news of impending war. In Germany, for example, there was a difference in the reactions of young and old, urban and rural Germans. Geoffrey Verhey suspects that in 1914 many people were carried away by the crowds. However, he concludes that this was not a ‘transformation experience in which all Germans became fraternal’.

Enthusiasts were mainly youths, and there is no evidence of workers in the photographic evidence we have. Moreover, war enthusiasm appears largely to have been an urban phenomenon.

Conclusion: no uniform enthusiasm for war

In summary, based on the available evidence it is fair to conclude that there was no uniform enthusiasm for war in 1914. Ultimately, pre-war divisions were at best papered-over by this brief unifying experience. When faced by years of war and hardship, cracks began to appear, and governments were soon preoccupied, as they had been before the war, with trying to contain and manage popular discontent. Strikes on the home-front, and desertion and even mutinies on the front threatened the governments’ war efforts as populations tired of warfare.

An example is the French mutinies of April-July 1917 (kept secret at the time), when large numbers of infantry soldiers refused to fight. Some twenty-thousand soldiers were court-martialled as a result, though the number of those executed was much smaller, at around 50 (there are no precise figures available). In the summer of 1917, the rebelling soldiers were won over by the military leaders and worse consequences were avoided.

When the pressures of war led to mutiny in Russia in 1916 and 1917, the result was defeat and revolution; while in Germany, the mutiny of Germany’s sailors helped bring about the end of a war that, by the autumn of 1918, the Germans could no longer win.

This page is part of our collection about the origins of the First World War.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews