1 Empires as systems of power

On 19 July 1842, ships of the Royal Navy and East India Company bombarded Zhenjiang (known in older European works as Chinkiang) – a city 120 miles (190 km) up the River Yangzi (Yangtze). The ships landed Royal Marines and company troops, including Indian sepoys (infantry), totalling around 7000 men. This force stormed the city, leaving the British in control of Zhenjiang, and so of the junction between China’s greatest river, the Yangzi, and the world’s longest artificial waterway, the Grand Canal. British sea and waterborne forces now had the Chinese land-based empire by its throat.

To understand why this was so, we need to understand how the Chinese empire worked; and to do this we need to look at empire as a ‘system of power’. In particular, we need to understand just how vital the Yangzi and Grand Canal were to its internal mechanisms. The Yangzi extended from Shanghai near China’s east coast, past Zhenjiang, inland to the southern capital of Nanjing, and further westwards. It constituted a massive internal artery for east–west communications: stretching 3500 miles (5630 km) from its source on the Tibetan plateau to its estuary at the sea. Hence its modern Chinese name: Changjiang, meaning ‘long river’.

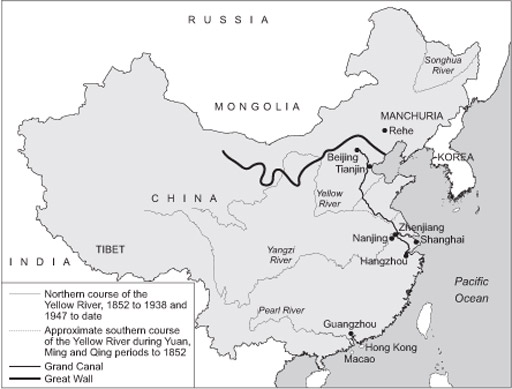

The Yangzi was joined to China’s other great east–west flowing rivers by the Grand Canal, which intersected them roughly at right angles. This latter provided a major north–south artery, stretching 1100 miles (1770 km) from Hangzhou (Hangchow) in south China to Beijing in the north. As such it made vital connections: between natural rivers; between the southern (Nanjing) and northern (Beijing) capitals and dialect areas; and between the great southern rice bowl and the northern plains. Like Russia, the Qing (Ch’ing) system, as a land empire, relied heavily on such inland waterways. You can think of China as an empire that grew up around the great Yellow River in the north, and extended by joining this to other waterborne systems via the Grand Canal and via the coast, and thereby also connecting to the PearlRiver basin in the south (see Figure 1). If you conceive of China as a system bound together this way, rather than merely as a land mass with the Great Wall keeping out central Asian horsemen, the seriousness of China’s defeat at Zhenjiang becomes clear.

The loss of control of these arteries for tax, trade, grains, reinforcements, and for the emperor to reach his inland cities, was thus one factor in bringing the Qing emperor to sue for peace. As long as the British had hammered away only at the margins, the coastal ports and downriver, he could continue the First Anglo-Chinese War (the ‘Opium War’, 1839–42). These external pinpricks were like so many cuts on a rhinoceros hide. Until this last blow, the Chinese land empire could still ensure that tax flowed, and food circulated. But once the yi – barbarians, as the Chinese termed foreigners – had penetrated to the heart of its interior communications, the game was up: regardless of the fact that, at around 400 million, China’s mid-century population dwarfed Britain’s 18.5 million (1841).

Little more than a month later, on 29 August 1842, China signed the Treaty of Nanjing (Nanking). This confirmed cession of the island of Hong Kong to Britain, the opening of five ‘treaty ports’ to British foreign trade and residence, and payment of an indemnity. Strangely, though, the sale of opium, the confiscation of which had been the trigger for war, was not explicitly legalised. This treaty marked the beginning of a serious decline in China’s fortunes as an empire – the Grand Canal itself falling into serious disrepair – and the beginning of Britain’s informal imperialism in China.

Why start with this one battle and place? Because they embody a clash between radically different ways of ‘doing’ empire: militarily, economically, administratively and in terms of ideas. By forcing us to view this moment in the First Anglo-Chinese War as a clash of two empires as distinct ‘systems of power’, it gets to the heart of the question ‘How do empires work?’ For the moment Zhenjiang fell was also the point when a European maritime empire finally persuaded the Qing land empire, after decades of intermittent negotiation and three years of open war, that it had met its match. What I propose in the rest of this course, then, is to continue to open up the question that ‘How do Empires Work’, by unpacking this one incident.

First, some additional words about the opponents at the July 1842 battle for Zhenjiang.