1.2 Sources for the Trojan War

It’s important to remember that there are variations on this story, and that the narrative is not fixed in one version; for example, some ancient authors wrote that Helen did not actually go to Troy, but rather a ‘phantom’ version of her created by Aphrodite did, while the real Helen was concealed in Egypt. The Iliad, too, is only a version of the story. We can see multiple versions in a variety of sources – and, crucially, not all of these sources are textual.

Activity 1

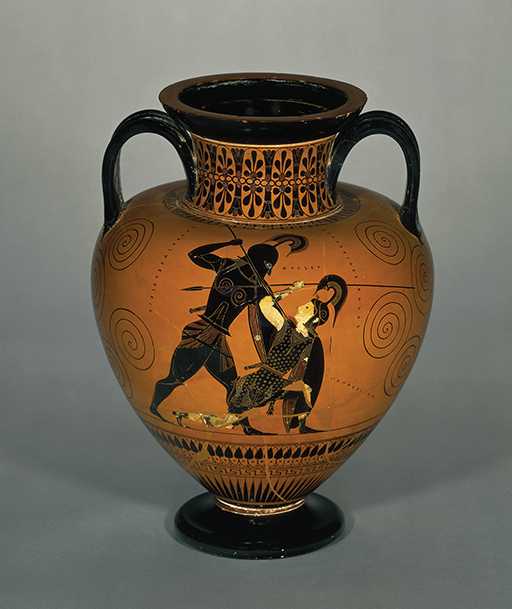

Another source for the Trojan story is Greek pottery. Look at the images below. Can you identify from the summary of the Trojan War which part of the story each of the images relates to?

Discussion

- Figure 2 depicts Achilles tying the body of Hector onto his chariot, in order to drag it around the walls of Troy three times in revenge for the killing of Patroclus.

- Figure 3 depicts the Trojan Horse, the famous ruse by which the Greeks were able to enter Troy and bring about the sack of the city.

- Figure 4 depicts Achilles and the Amazon Queen Penthesilea. Achilles is portrayed as obviously dominant, towering over Penthesilea, seemingly about to deliver the deathblow. We know that the figure of Penthesilea is female because she is painted in white and depicted with fewer muscles than Achilles.

- Figure 5 is from another ancient Greek pot that depicts Ajax rescuing the body of Achilles from the battlefield for burial. Two inscriptions (in Greek) mark the characters involved.

Out of these four images, only that in Figure 2 is narrated by the Iliad. From this fact, we can learn two things. Firstly, the narrative of the Iliad is only one part of a much wider mythical tapestry of the Troy story. The story extends on either side of the narrative, and even events that do occur in the poem could be told in different ways: for example, the scene in Figure 2 is not exactly what we ‘see’ in Homer, though it addresses the same moment in the narrative. Secondly, the numerous scenes from the Troy story that appear on Greek ceramics and other visual sources from the Greek world are almost certainly not illustrations of the Iliad itself, but rather of the wider myth. Homer’s Iliad, then, is simply one version of a part of the Troy story.

You now have a sense of the Trojan War and what happened in it. In this next activity you will learn about Homer’s take on the tradition.

Activity 2

Watch this short animation, ‘Troy Story I’, which summarises the narrative of Homer’s Iliad. Then reread the summary of the Trojan War story in Section 1. How does the plot of the animation compare to it?

Transcript: Video 1 Troy Story I: the Iliad

Discussion

The main theme of the Iliad is Achilles’ anger. To summarise: The poem begins with Achilles getting angry with Agamemnon, for taking the woman he had been awarded as a prize, Briseis; it ends with the burial of Hector, the Trojans’ greatest fighter, killed by Achilles, angry with Hector for having killed his best friend, Patroclus. Did you notice what the Iliad doesn’t narrate? It doesn’t tell us how the Trojan War started, or how it will end. In fact the whole of the Iliad covers only about 51 days in a 10-year war, and even then the main chunk of the text only really concerns a mere 3 days of fighting!

Optional activity

Although the Odyssey won’t be discussed in detail in this course, you might enjoy watching this second Troy Story animation, which explains the plot of this poem about Odysseus’ arduous journey home from Troy to Ithaca and the problems he encountered once he arrived there. The skills you learn in this OpenLearn course should prepare you to read both poems, as they employ similar techniques of oral poetry.

Transcript: Video 2 Troy Story II: the Odyssey

Despite the fact that the Iliad is a (very) long poem, Homer is remarkably concentrated on a single, fleeting episode in a much longer conflict. At the same time, he still manages to evoke the war as a whole. To take one example: Homer relates that, when news of the Trojan hero Hector’s death reached the Trojans holed up in the city, they wailed ‘as if the whole of jutting Ilium was now smouldering / with fire all the way from its top to its bottom’ (Iliad 22.410–411). Homer doesn’t need to narrate the fall of Troy because: (i) his ancient audience knew the broader outline of the Troy story; and (ii) he has shown by this point in the narrative that, with the death of Hector, Troy is doomed to fall.

It’s clear already, then, that the Iliad doesn’t tell the whole story of the Trojan War. In what follows you’ll start to think about what Homer does focus on.