3.2 Pietas vs furor

A very different quality from pietas is furor, from which we derive the English words ‘fury’ and ‘furious’. In the Aeneid, furor is found when emotions or other violent forces are allowed to run uncontrolled. Thus, for example, when people act out of passionate love or anger, their behaviour is associated with furor. War always runs the risk of lapsing into furor because of the emotions involved and the devastation it causes, and civil war in particular, which is presented as irrational and hate-filled, is a particular evil caused by furor. Throughout the poem, Virgil uses imagery of powerful forces of nature to describe furor; for example, fire, storm winds and darkness, and lashing waves.

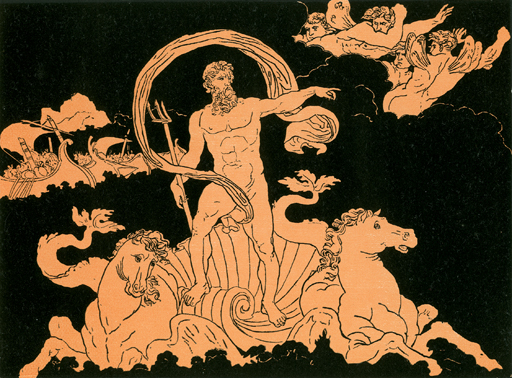

The clash between furor and pietas is set up in symbolic terms near the start of the poem, when the sea-god Neptune calms the storm sent by Juno (who with her passionate hatred of the Roman destiny embodies the forces of furor). I’ve given you the text below, and have indicated where the words furor and pietas occur in the original Latin.

As often, when rebellion breaks out in a great nation,

and the common rabble rage with passion [furor], and soon stones

and fiery torches fly (frenzy supplying weapons),

if they then see a man of great virtue [pietas], and weighty service,

they are silent, and stand there listening attentively:

he sways their passions with his words and soothes their hearts:

so all the uproar of the ocean died, as soon as their father,

gazing over the water, carried through the clear sky, wheeled

his horses, and gave them their head, flying behind in his chariot.

The symbolism of this passage is made clear: we are told that the crowd is influenced by furor, which is causing their anger to boil over into violence. Conversely, the wise statesman is a man of pietas who uses this to calm their anger and return them to their senses. Virgil here switches the usual set of conventions: rather than using imagery from the natural world to describe human passions (e.g. anger is like a storm), he uses imagery from political life to describe a natural phenomenon (a storm is like political discord). This is the passage that first sets up the idea that pietas can overcome furor, and so it’s significant that Virgil chooses the sphere of politics and civil discord as a frame. This will be relevant throughout the Aeneid, as we see Aeneas trying to be a good leader, and it becomes especially relevant in the second half of the poem, in which we see furor causing hatred and war in Italy. It’s also relevant to Virgil’s contemporary readers, who may think of the conflicts they have lived through. One possibility is that we are meant to identify the statesman of pietas in this passage with Augustus, who also imposed order after a time of chaos. Alternatively, the statesman could just be an abstract idealised figure, and a model for all leaders to aspire to.