In 2007 a travel journalist, Laura Knight, reviewed the Balmoral Hotel in Edinburgh for The Times:

The windows of room 652 give me a whiff of Hogwarts school for wizards. Two tiny apertures high up in the wall look out onto the cornices and cupolas of the century-old roof, while a pair of round windows frame a stunning view of the Edinburgh skyline. Squint and you could almost imagine Hermione curled up with a spell book on the windowsill.

It was in this room that J.K.Rowling finished Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows in January. I sit at the modern desk where, presumably, she put an end to either Harry or He Who Must Not Be Named. Then I plump down on the beige sofa, the dark leather chairs, and the soft bed with its leather headboard, just in case she doesn’t write at a desk.[1]

In fact, according to Rowling herself, the room she finished the novel in was room 552. Here she left a memorial inscription, fittingly on a plaster bust of Hermes, messenger to the gods: ‘J.K. Rowling/finished writing/Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows/in this room (552)/on 11th Jan 2007’. Following her confession to this in a tweet of 11 Jan 2016, the room was transformed into the J.K. Rowling suite, complete with owl knocker. The desk ‘the very same one used by J.K. Rowling to write those crucial last chapters’ was within the year staged and represented as such, the bust of Hermes was protected by a glass cabinet, a framed replica of Rowling’s inscription is now displayed on the wall behind it, and there are photographs of the whole on the internet.

Finished Hallows 9 yrs ago today. Celebrated by graffiti-ing a bust in my hotel room. Never do this. It's wrong. pic.twitter.com/HsqQKydY68

— J.K. Rowling (@jk_rowling) January 11, 2016

There are two interesting things about Laura Knight’s write-up. The first is the way that the author is represented as existing at the same level of reality as the author’s fictional characters, not as finishing the last manuscript pages of a book, but as ‘putting an end’ to her characters. Secondly, although the journalist may have been in the wrong room, trying out the wrong chairs, desk and bed as possible sites of writing, she knew that such a site must have existed, she knew that it offered privileged access to ‘magic’, and she knew what to do to access it – that is to say, to sit in the author’s chair and preferably at their desk. In this she rehearsed a well-worn cliché, one that first emerges around the 1780s when tourists first developed the widespread habit of visiting locations associated with writers and their work in pursuit of supplementing the experience of reading with something more immediate, sensory, and experimental.

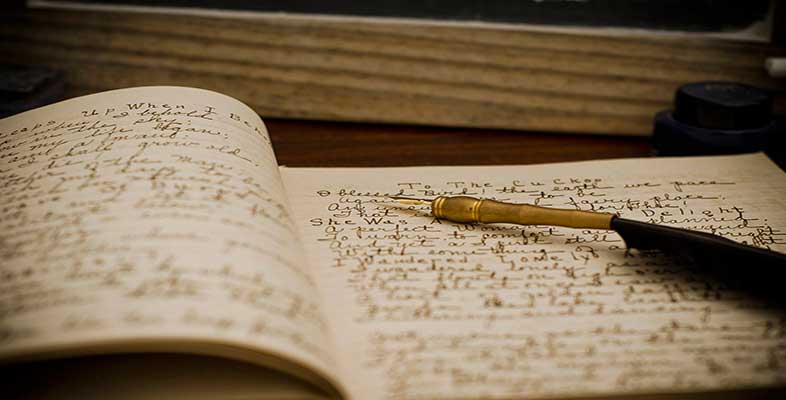

What exactly then does the writer’s desk and chair ‘mean’? What is its value? Commercially, it has lent lustre to the hotel for sure, and doubtless the suite commands a premium price. Culturally, the writer’s desk typically stages the place and end of the work of writing and the beginning of the existence of it as a book. It also stages the author as existing before, after, and beyond the book. Rowling’s handwritten scrawl entrusted to Hermes as divine messenger insists that there is something left over even after the end of the epilogue to the Deathly Hallows; that something is surely what the literary tourist is looking for.

References and further information

[1] Jane Knight ‘Mystery Guest We Send a Writer Under the Covers…This Week the Balmoral Hotel, Princes Street, Edinburgh The Times cutting, n.d. c. 2007 p. 26

Professor Watson is working on a book called The Author’s Effects: A Poetics of the Writer’s House Museum.

Why do people want to visit writers' homes?

Explore writing and reading with a FREE course

This article is part of our Harry Potter collection - a series of academic insights exploring some of the themes, interests and general wizardry in the novels written by J.K. Rowling.

This article is part of our Harry Potter collection - a series of academic insights exploring some of the themes, interests and general wizardry in the novels written by J.K. Rowling.

You can view our Happy Birthday Harry Potter! hub here to read all the articles. Mischief managed!

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews