1.1 Who is religious in Britain?

Religion in contemporary Britain appears to be something of a contradiction. The percentage of the population who are active religious adherents is falling. The number of people identifying as ‘non-religious’ accounts, by some estimates, for nearly half of the British population (NatCen Social Research, 2016).

Yet religion retains immense cultural influence, and the absolute numbers of religiously motivated people remain significant enough to require consideration in local and national policy decisions. A variety of religiously committed people are also regularly encountered on high streets and neighbourhoods throughout Britain.

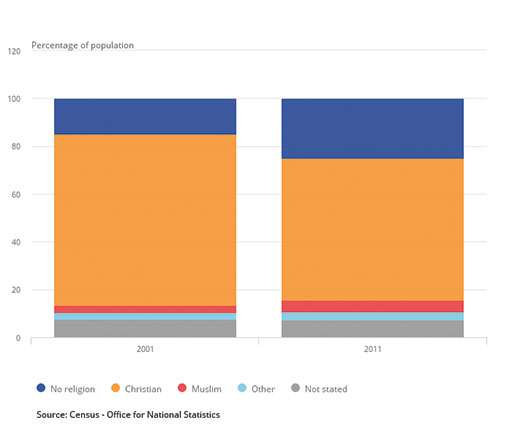

The figure below compares how the population of England and Wales defined their religious identity in the 2001 and 2011 censuses.

The largest section of the population is represented in orange, those who identify with the general label of ‘Christian’. This included 69% of the population of England and Wales in the 2011 census (White, 2012). In Scotland, 54% of the population identified as Christian (National Records of Scotland, 2013a).

The most noticeable change between 2001 and 2011 is the increase in the blue ‘No religion’ identification. In 2011, nearly 25% of the population of England and Wales were happy to identify with this label (White, 2012). In Scotland, 37% of the population identified as non-believers in the 2011 census (National Records of Scotland, 2013b).

Yet what exactly it means to self-identify as ‘non-religious’ is a subject that is not very well understood. Recent research suggests that being ‘non-religious’ does not usually equate to being a committed atheist or humanist. Rather identifying as ‘non-religious’ might signify a position of personal disinterest about matters relating to religion (Lee, 2016).

Reinforcing the continuing cultural influence of Christianity, the Church of England has been established in law since 1534, and the national churches of Wales and Scotland still have significant political and popular influence in their respective areas.

The Christian religion underpins much of Britain’s legal and cultural assumptions. The Church of England exerts influence on legislation through the ‘Lords Spiritual’, 26 bishops who sit in the House of Lords.

Where religion ends and culture begins is not necessarily straightforward. This is one of many things the study of religion exposes. The unique history of Northern Ireland creates a very different religious landscape. Here 41% identified as Catholic and 42% identified with Presbyterian, Church of Ireland or other Protestant denominations. Those identified as non-religious made up less than 17% of the population in 2011 (Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, 2012).

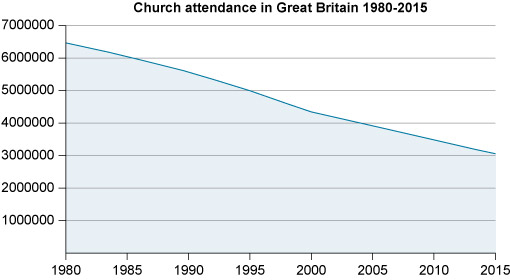

Despite the continued legal and cultural significance of Christianity in Britain, it is also clear that only a small proportion of the British population attend church on Sunday. Recent counts put this number as less than 6% of the British population. Yet the absolute number of regular churchgoers still total over 3 million, a significant section of the population. (Brierley in McAndrew, 2016)