9 Graffiti in advertising

In addition to entering the realm of mainstream galleries and museums, graffiti art (sometimes also referred to as ‘aerosol art’) is also increasingly used commercially, for example to advertise products (Imam, 2012). In an article published in the academic journal Visual Communication Quarterly, the scholar Kara-Jane Lombard uses ‘Tats Cru’ as an example of the ‘commercial incorporation’ of hip hop graffiti. She explains:

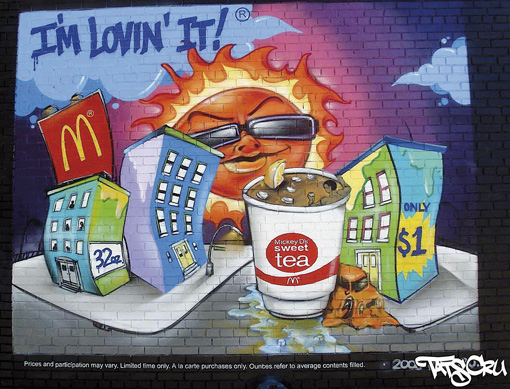

One of the most successful aerosol art businesses, Tats Cru was once a graffiti crew that wrote illegally on subway trains. Now legitimate aerosol artists, the group incorporated in the early 1990s and has been commissioned to do work for a variety of companies such as small neighborhood businesses as well as bigger corporations such as Coca-Cola, Firestone, Reebok, the Bronx Museum of Arts, and Chivas Regal. They have also been featured in media outlets such as the New York Times, USA Today, CNN, and BBC.

Activity 7 Graffiti in advertising

Take a look at examples from Tats Cru’s portfolio on their website [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .

Alternatively, see whether you can find any other examples where graffiti has been used to advertise products, either in newspapers, on billboards or packaging, or on the internet (using search terms such as ‘Graffiti and advertising’).

In the text box below, note down your response to the following question:

Why do companies (like McDonald’s, Coca-Cola or Reebok) use graffiti for advertising?

Discussion

There are a range of possible reasons. Graffiti is associated with youth culture and with being young, rebellious, brave and ‘trendy’. Companies that use graffiti in adverts are possibly hoping that customers will associate these qualities with the purchase, use or consumption of the products that are being advertised.

Some critics have argued that the use of graffiti for mainstream commercial purposes, such as advertising, amounts to a sell-out. They feel it degrades this form of art or even renders it meaningless (Fuchs, 2008). However, others have pointed out that the use of graffiti in advertising is an increasingly complex process, where some companies are making real efforts to work together with artists (Lombard, 2013).

It is also important to bear in mind that graffiti artists are often involved in a range of different forms of graffiti. Banksy, for example, uses both illicit street art (including graffiti) and official exhibitions at public galleries and publications (such as books) to exhibit his work. In the video linked in Activity 6, it also became apparent that he is not alone in this approach and that many graffiti artists use both officially sanctioned and illicit forms of graffiti for different purposes and reasons. Some artist welcome the public recognition and financial rewards linked to the official exhibition of graffiti in prestigious art galleries and other aspects of mainstream culture, but still regard illicit graffiti as the ‘real thing’. As graffiti artists Cept and Stik explain:

Cept: ‘The fun of it is [...] painting where you shouldn’t be and that’s where the real graffiti works. It’s all good spending all day doing a piece and taking your time, but it is not half as fun as doing it illegally.’

Stik: ‘Its like being part of the biggest gallery in the world [...] because you are part of the street that is open 24 hours a day and 7 days a week and it is uncensored.’