The word Brexit is now so familiar that it is easy to forget just how new it is. Brexit was officially recognised as an English word as late as December 2016 through its inclusion in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). The meaning is given as "the (proposed) withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union, and the political process associated with it". In linguistic terms, Brexit is both an English language phenomenon and a global language phenomenon. As well as its now-familiar use in English it has been adopted by just about every European language and by some Asian languages. It therefore falls into the class of international language words like hotel and taxi. It’s even become a place name as the French town of Beaucaire now has rue de Brexit, ironically a turning off rue Robert Schuman and a short distance from avenue Jean Monnet, both named in honour of EU founding figures.

The word Brexit is now so familiar that it is easy to forget just how new it is. Brexit was officially recognised as an English word as late as December 2016 through its inclusion in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). The meaning is given as "the (proposed) withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union, and the political process associated with it". In linguistic terms, Brexit is both an English language phenomenon and a global language phenomenon. As well as its now-familiar use in English it has been adopted by just about every European language and by some Asian languages. It therefore falls into the class of international language words like hotel and taxi. It’s even become a place name as the French town of Beaucaire now has rue de Brexit, ironically a turning off rue Robert Schuman and a short distance from avenue Jean Monnet, both named in honour of EU founding figures.

Such a widely used word might be expected to have been around for some time. However the earliest use seems to be as recent as May 2012, when the term was used by the financial press for a possible British exit from the EU, and mostly with the spelling Brixit. It was modelled on Grexit, the term that had been coined for a possible (and at that time far more likely) Greek exit from both the euro currency and the EU, and as such appears to have been invented by multiple journalists around the same time. It is unlikely that the first creator of the term will ever be identified. In just four years the term developed from this financial niche to become part of the core vocabulary of English.

The OED has recognised Brexit solely as a noun, though this will soon need to be revised. In popular usage it is already being used as a verb: the UK will Brexit in 2019. It can be used as an adjective too: the Brexit referendum. To date it’s not quite established itself as an adverb – it seems that something cannot be done Brexitly – though it is already part of a set adverbial phrase: despite Brexit.

Brexit has produced nouns for supporters, both Brexiter and Brexiteer. These are not synonyms. Rather Brexiter is used to describe someone who accepts Brexit with or without enthusiasm, while Brexiteer is used for someone enthused by Brexit, the term parallel with such euphemistic and even romantic forms as cavalier and chevalier. Characteristic of a well-established noun is that it has antonyms, and Brexiter has produced its opposite in Remainer, orthographically usually with an initial capital as an overt pairing with Brexiter. Brexiteers use the term Remoaner for what they see as a bad loser who wants to set aside the referendum result. Some collocations have become established: hard Brexit, soft Brexit, clean Brexit. Prime Minister Theresa May has provided the definition that Brexit means Brexit and has set out her views on hard or soft Brexit by saying her goal is a red, white and blue Brexit. The word is clearly active in English.

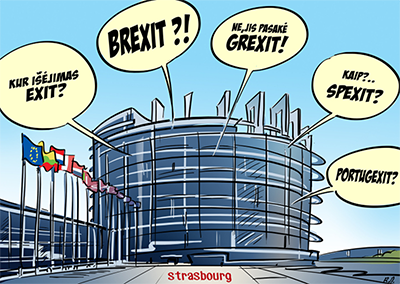

Speculation that other nations may start a process of withdrawing from the EU has led to many parallel constructions. Some seem to work well. Frexit seems to be the only possible term for a possible French exit. Others seem problematic. Would exit of the Netherlands (Holland) prompt Nexit or Hexit? Does an Italian exit prompt Italexit or Itexit? Or would the form Outaly catch on? If Spain leaves then Spexit sounds possible in English, but in the event of a German departure, Germexit surely doesn’t work.

The American press briefly had the term Califexit, to refer to possible succession of California from the USA following Donald Trump’s election victory. Humorous coinages have included Edexit (the departure of Ed Balls from Strictly Come Dancing), and in popular usage the abrupt departure of anyone from anything can prompt a comparable creation. Political thinking has produced the term Lexit (support of left-wing parties in Europe for exit from the EU) but curiously Rexit does not seem to have emerged for the more common phenomenon of support by right-wing parties.

Inventive use has created a host of comic forms. Bregret has appeared (for regret of Brexit), along with dog’s Brexit and full English Brexit as comments on the process. English speakers have coined the French phrase je ne Bregret rien! Brexit is now both an established word and a source of linguistic invention. It’s here to stay.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

Intresting article!

I am hearing the word Brexit almost everyday on the news, but It's meaning did not come across.

I will read read this article as much as I can to absorve the importance of it's meaning.

Carla Amelia Marcus - 1 August 2017 7:20pm

Intresting article!

I am hearing the word Brexit almost everyday on the news, but It's meaning did not come across.

I will read read this article as much as I can to absorve the importance of it's meaning.