The Old Bull in Inkberrow, the model for The Bull in Ambridge

The Old Bull in Inkberrow, the model for The Bull in Ambridge

When it comes to who’s who in the Archers, Brian and Jennifer Aldridge are landed gentry, the Grundys are struggling farm-workers and Lynda Snell is snooty. How do we know? We trust the evidence of our ears – it’s clear from the way they speak.

Accents play a vital role in building character in radio dramas – and The Archers is no different. Unlike TV and film – which have the added visual resource of physical appearance and clothes – radio relies purely on the voice when it comes to creating that initial impression.

In real life, the way we speak is central to the way we are perceived by others. We use our voices both consciously (often strategically) and unconsciously in order to help construct the very identities that we perform and negotiate in our day-to-day interactions. This is not to say that we are all in the habit of taking on completely different personalities when we feel like it. Rather it is an acknowledgement of the fact that our identities are multiple, multifaceted and fluid. We use our voices, as well as our dress and behaviour, to subtly adjust our identities according to the context in which we find ourselves.

Voicing class distinctions

In radio, TV, and film, accent is used a great deal in the creation of character. It is well known that in American productions, a British accent is often used to signify a “villain” and “foreign” accents are also often used this way in animated films and TV programmes. By doing this, the producers are at the same time buying into – and reinforcing – social stereotypes that we have all grown up with. There is no linguistic reason for an accent to be associated with particular characteristics – we are simply loading the voice with the social baggage it has culturally acquired over generations.

What Clarrie sounds like.

The Archers is no stranger to the use of stereotypical accents in its construction of the social hierarchy of Ambridge. Distinctions of status and class are instantly defined in the contrasting voices of characters such as Brian and Jennifer Aldridge on the one hand and Eddie and Clarrie Grundy on the other. Brian and the rest of the Aldridges are given the Received Pronunciation (RP) of prestige and power, while the Grundys are given the generic “rural” accent of struggling farm-hand.

Never mind that the Grundy’s accents are hard to place regionally, the drawn-out vowels in words such as “lot”, “palm” and “goat” – and the full pronunciation of “r” in words such as “farmer”, are enough to signify “country folk” to city-dwelling listeners.

Of course, for regular listeners, the accents are just part and parcel of the characters we’ve known for years. We don’t only rely on Lynda Snell’s trademark enunciation to tell us she thinks she’s a cut above the rest of the community, we know this from her behaviour. Just as we know that Ian Craig is a kind and trustworthy friend.

Status and solidarity

In order to attempt to isolate the role of accent in the process of characterisation, I carried out a preliminary study using people who don’t listen to The Archers. I played the participants short, content-neutral clips of various characters and asked them to rate the voices on measurements of status (posh, intelligent, educated) and solidarity (friendly, kind, trustworthy).

Sure enough, the assessments followed a familiar pattern, with characters such as Brian, Jennifer, Lynda and Jim Lloyd scoring highly on measures of status, but characters such as Clarrie, Eddie, Emma and Jazzer taking their place on measures of solidarity.

What Jazzer sounds like.

This would suggest that the required cultural associations are firmly in place, allowing the producers to make use of these stereotypes. Indeed, this is usually a safe bet in traditionally class-conscious Britain, where accents have always been seen as an indication of social position.

But when those cultural associations aren’t guaranteed, the story changes. When I isolated the assessments of people who didn’t grow up in the UK – and for whom English is a second language – the neat and predictable pattern largely disappeared.

For this group, Brian did not sound so posh. In fact, Clarrie was identified by some as having a posh voice, along with Emma and even Eddie. On this and many of the measures, the results were less focused, covering a greater range, suggesting that respondents were using less consistent criteria to evaluate the voices.

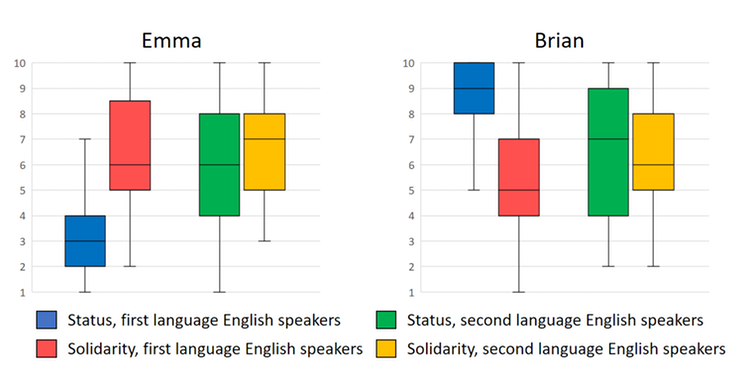

The chart below illustrates this difference. It shows the range of status and solidarity measures for Emma and Brian, for both the first language English speakers and second language English speakers. Notice how the clear differences between status and solidarity for the first language speakers disappear for the second language speakers.

Measures of status and solidarity for Emma and Brian.

Measures of status and solidarity for Emma and Brian.

How Brian sounds (with his wife Jennifer)

How Emma sounds.

![]() It would be hard to pinpoint the location of Borsetshire if we were using accent alone. The apparently local non-RP accents display a number of features from a variety of UK regions. However, the continued English preoccupation with accent and social class means that we are left in no doubt as to the pecking order of the residents of Ambridge.

It would be hard to pinpoint the location of Borsetshire if we were using accent alone. The apparently local non-RP accents display a number of features from a variety of UK regions. However, the continued English preoccupation with accent and social class means that we are left in no doubt as to the pecking order of the residents of Ambridge.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Rate and Review

Rate this audio

Review this audio

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Audio reviews