Image credit: Speedpropertybuyers

The Irish are great storytellers, illuminated through the centuries by Beckett, Yeats, O’Brien, Shaw, Wilde, Binchy, Enright and Joyce to name a few. The great English lexicographer, Samuel Johnson, said that narrative is the superior form of knowledge, whilst the German philosopher, Hegel, stated that knowledge proceeds through conversation. Yet in the face of the impact of Brexit on the whole of Ireland as the only story in town, does economics lack these two basic elements to create knowledge?

Part of the answer lies in the academic discipline’s desperate attempt to be viewed as a science by reducing its methods to that of physics. In combination with ‘bad’ mathematics, this physics envy has produced a desiccated form of investigation in which a contextual narrative of society, polity and culture is almost absent. As George Shackle, the Cambridge economist observed: to be an economist one has to be an anthropologist; political scientist; mathematician; philosopher; and sociologist with an interest in economics. It is these characteristics that are vital in creating a narrative and conversation about Brexit.

Brexit's impact on Ireland

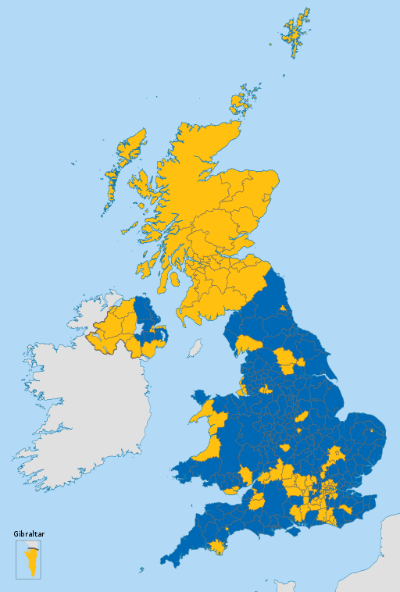

Map of the United Kingdom showing the voting areas for the European Union membership referendum, 2016. Blue = Leave Yellow = Remain

Map of the United Kingdom showing the voting areas for the European Union membership referendum, 2016. Blue = Leave Yellow = Remain

The treatment of Brexit as an event that follows on from the EU Referendum vote in June 2016 rather than a process has generated opposing views. One is that the UK will regain an imagined Arcadian Imperium past (one that never existed) outside the EU. The other is, that without EU membership, the UK’s economy will go to hell in a handcart. Neither encompasses a consistent narrative and it could be argued that the current state of negotiations between the Westminster government and the EU is equivalent to the Game of Thrones. This medieval storytelling epic has metaphorical utility for Northern Ireland. It has become a global production system, with filming and production activities across various European locales, including Northern Ireland. Underpinning this regionally distributed system is a set of Global Value Chains (GVCs): the basis of trade in modern economies. These include associated activities such as culture, leisure and tourism as well as related business and financial services. It follows that a thorough underlying narrative is an imperative in trying to understand the economic implications of this global brand possibly retreating from Ireland following Brexit.

A similar argument can be made for the crucial Agri-food sector, whose production crisscrosses the Irish border and the rest of the UK. Brexit appears to be a de-globalising project. Graham Brownlow (OUB) and I examined the question Can the Economy be Irish? at the ESRC Festival of Social Science in Belfast in November this year. In order to explore the complexities of the GVCs that underpin this sector, we need to go beyond its contribution to output, investment and employment. An economic narrative that includes the importance of this cross-border sector to the sense of rural culture and the very notion of Irishness is missing in assessing the impact of Brexit on the island of Ireland. Moreover, such a narrative enables greater insight into the thorny issue of the border question. As a senior rural affairs spokesperson quipped, “Irish cows don’t respect borders”, but this seemingly trivial remark is actually relevant in seeking more imaginative solutions to the border question that conventional economic analysis cannot contribute to.

Economic implications

Ireland is a unique case in respect of Brexit and future relations with the EU. The Good Friday Agreement, that ended the internecine conflict, incorporates socio-economic rights for all citizens in the island of Ireland that are not available to citizens in the rest of the UK. These are fundamental resources in any system that promotes economic citizenship for all. This is part of the story that needs to be told in any economic appraisal of the impact of Brexit as an ongoing process in the longer term. The combination of a Shackle-type framework, within a storytelling practice that the Irish have made famous, seems to be an absolute necessity in addressing the greatest challenge Europe has faced in nearly seventy years. It would also contribute to sense-making within conventional economics that it currently appears to lack.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews