Young girls line up at a feeding centre in Mogadishu, Somalia, on March 9, 2017.

Young girls line up at a feeding centre in Mogadishu, Somalia, on March 9, 2017.

A severe drought threatens millions of people in East Africa. Crop harvests are well below normal and the price of food has doubled across much of Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia and nearby countries. ![]()

The last major drought in the region, in 2011, caused hundreds of thousands of deaths. They are becoming more frequent and more intense – and each has a disastrous impact on the economies of nations and livelihoods of people.

So what is causing these droughts? And why are they becoming more common?

At least part of the explanation lies with a climate phenomenon known as the “Indian Ocean Dipole”. The dipole, often called the Indian Niño due to its similarity with El Niño, is not as well known as its Pacific equivalent. Indeed, it was only properly identified by a team of Japanese researchers in the late 1990s.

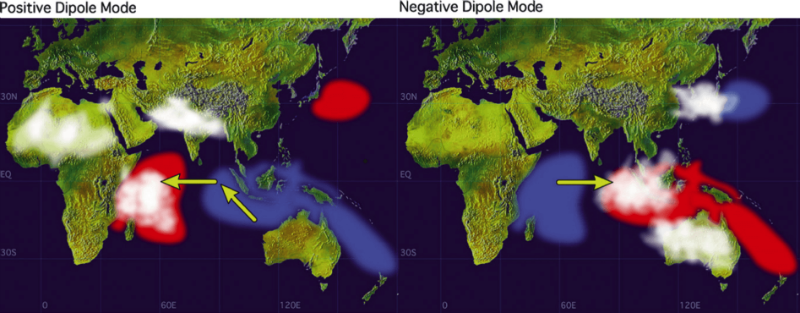

Sea surface temperature anomalies during Indian Ocean Dipoles. Arrows indicate wind direction, white patches are areas with more clouds and rain.

Sea surface temperature anomalies during Indian Ocean Dipoles. Arrows indicate wind direction, white patches are areas with more clouds and rain.

The dipole refers to the sea’s surface temperatures in the eastern Indian Ocean off Indonesia, cycling between cold and warm compared to the western part of the ocean. Some years the temperature difference is far greater than others.

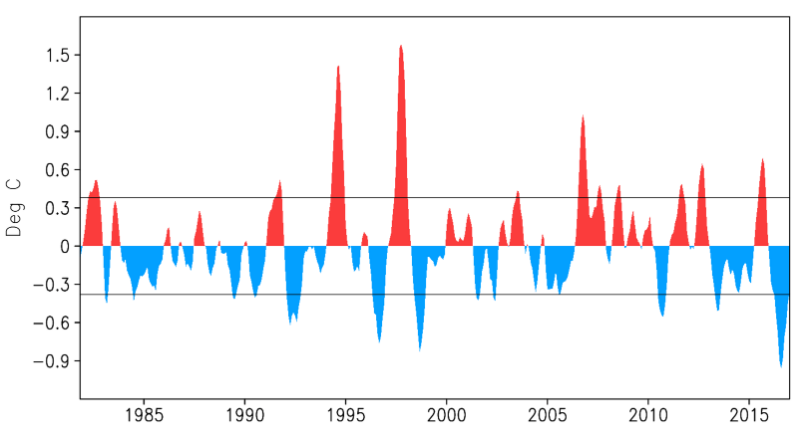

We are currently coming out of a particularly strong dipole. At its peak, in summer 2016, the sea off the Indonesian coast was 1℃ or so warmer than waters a few thousand kilometres to the west.

Temperature differences between east and west Indian Ocean.

Temperature differences between east and west Indian Ocean.

Warmer seas evaporate more water and, on this sort of vast scale, a relatively small temperature difference can have a big effect. In this case it meant there was a lot more moisture in the atmosphere above the eastern Indian Ocean.

As moist air is cooler than dry air, this in turn affected the prevailing winds. Wind is simply the atmosphere trying to equalise differences in temperature, density and pressure. Therefore, to “even out” the unusually cool air, a warm, dry wind began to blow eastwards from Africa across the ocean.

This is disastrous for farmers in the Horn of Africa who rely on moisture from the Indian Ocean to generate the “short rains” that run from October to December and the “long rains” from March to June. With winds blowing out to sea, the air was even drier than usual. The 2016 short rains were a month late and in some places failed entirely. Aid agencies warned the failure of these rains could trigger mass famine across northern Kenya, South Sudan, Somalia and eastern Ethiopia.

Things will not improve any time soon. As with El Niño, global warming means the Indian Ocean Dipole has become more extreme in recent years. In East Africa, these severe droughts will become the norm.

What can be done?

There are no easy answers. However, while we cannot control the Indian Ocean, we can change the way humans interact with the East African environment, making communities more resilient to climate change.

Past land use offers us some important clues. For example, a number of sites across East Africa demonstrate the impact of switching to more drought-sensitive New World crops such as maize. Maize was introduced in 1608 and since then it has largely replaced more traditional and drought-resistant crops such as cassava or sorghum.

Maize provides excellent calorific returns in good years, but it often fails and has challenges around infestation and storage during drought years.

Further lessons from history show us that pastoral communities have become less mobile. Livestock farmers are settling down and becoming increasingly reliant on irrigation and crop growing, which makes them more sensitive to drought. Competing demands to conserve land for wildlife add to the problems.

There are a few things East Africans can do to ease the impact of climate change, especially droughts. Livestock farmers could share large communal “grazing banks” to act as an insurance scheme and spread the risk of pasture failure. Pastoral movements could be better managed to ensure areas do not become overgrazed and conflicts with conservation areas are minimised. Mountain forests could be valued more and managed better to capture useful water without the need for costly and vulnerable irrigation systems. And finally farmers could switch to varieties of crops that are better at coping with climate variability.

The “Indian Niño” isn’t going anywhere, along with the regular and severe droughts it causes. People in East Africa must prepare.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews