3.4 Bears (continued)

3.4.1 Fasting in polar bears

Polar bears (U. maritimus) are almost entirely carnivorous and are the only living species of bear to obtain almost all their food from the sea. Their main prey is ringed seals (Phoca hispida), both adults and suckling pups; they catch the adults when they come up to breathe through holes in the ice, though detailed observations show that as few as one in five attempts results in a kill. The seals are born in holes in the snow, and their mothers leave them hidden there while they go to feed, returning to suckle them at least once a day. The young seals fatten and grow very rapidly on their mothers’ exceptionally rich milk. Until their fluffy white fur is replaced by the sleek, more waterproof adult coat, the young seals cannot enter the water even if it is accessible because they quickly get too cold. The seal breeding season in spring and early summer thus provides polar bears with plentiful prey.

SAQ 17

What features of the arctic environment enable the seals to maintain their population in spite of predation from bears?

Answer

The seals travel long distances and ice conditions suitable for breeding are not necessarily in the same place each year, so the bears may not find many of the seal breeding colonies.

How often are polar bears successful in finding food? Do they fast when out on the ice, as well as when in dens? Polar bears range over such a wide area of inhospitable terrain that such questions, though vital to the management of the species in the wild, are not easily answered by direct observation. The study of nitrogen metabolism in black bears suggests an indirect way of investigating such topics.

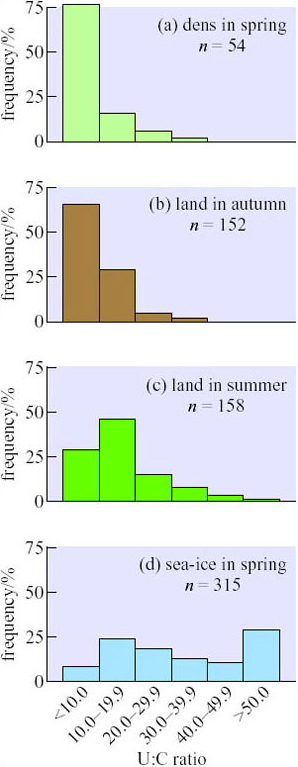

Figure 15 shows some measurement of the ratio of urea to creatinine in blood samples collected from polar bears in northern Canada that were temporarily sedated with drugs injected from a dart gun.

SAQ 18

What do these data suggest about food sources and hunting success in bears?

Answer

More than 75% of bears in dens (Figure 15a) had U:C ratios of 10 or less so they were obviously not eating, but the U:C ratios were 19.9 or lower in 70% of those caught on land in summer and autumn, showing that they were also fasting (Figures 15b and c). Out on the sea-ice in spring (Figure 15d), more than half the bears sampled had U:C ratios of 30 or more, indicating that they were feeding frequently. At least 10% of the bears in this sample were fasting: either they were inexperienced, inefficient or unlucky hunters of seals or (as quite frequently happens) they were forced to give up their kills to larger bears that threatened them. Alternatively, they may be ‘voluntarily’ anorexic while mating: during the spring, large males attend oestrous females closely and may fight with rivals, leaving little time for hunting.

Ice conditions that favour catching adult seals are strongly dependent upon weather and water currents, and so are widely scattered in space and time. Food supply is probably erratic even for the most proficient bears. Seal hunting is almost impossible for several months in the summer and autumn when the sea is unfrozen, and the only food available to polar bears is the odd bit of carrion and a very small quantity of plant food. The data in Figure 15 show that nearly all polar bears fast for long periods in the summer and that, for many, the food supply is unreliable even in winter and spring. Thus polar bears seem to adopt many of the metabolic features of winter dormancy in the omnivorous brown and black bears, while remaining active enough to be able to travel long distances between seal-hunting grounds. They become lethargic and remain inactive for long periods when weather conditions or terrain make hunting impossible, suggesting that they have become ‘dormant’ without actually being asleep in a den.

This theory is confirmed by observations on polar bears held temporarily in captivity. Bears caught in autumn were starved for 5–7 weeks, fed for 3 days, and then fasted again. Blood samples were taken just before and for several days after feeding, and the concentration of urea and creatinine measured. During the imposed fast, the U:C ratios averaged only 11.0, but rose abruptly to 32.0 after feeding and then declined to 22.8.

Polar bears are a relatively new species, almost certainly evolving from brown bears during the last 100 000 years. They must have inherited the capacity for dormancy from their omnivorous ancestors that fed mainly in the summer and autumn. In males and non-breeding females, dormancy takes the form of inactivity during the summer months and in winter, intermittent fasting between widely scattered and irregular feeding opportunities.

Breeding females undergo periods of fasting more closely tied to the seasons. Shortly before giving birth in December or January, the pregnant females migrate to areas where deep snow drifts suitable for making dens have formed against river banks or similar obstacles. Around Alaska, polar bears find denning places on the sea-ice but those around Svalbard and Hudson Bay in Canada travel inland, sometimes substantial distances. The mothers give birth in the snow den and suckle their cubs there for up to 5 months, during which time they remain inactive and do not feed at all, but they are alert and, so far as we know, the body temperature is normal.

Lactation is metabolically very demanding, especially during fasting. The mobilization of lipids, proteins and minerals from storage tissues and the skeleton and the synthesis of milk would produce more than enough heat as a by-product of metabolism to maintain normal body temperature. For obvious practical reasons, there are few physiological data on breeding polar bears. However, indigenous people who traditionally hunted the animals for their meat and skins report that bears in maternity dens are no soft target, and the adult females are quick to put up a fight.

Polar bear cubs are weaned over many months, and while food is scarce, mothers sometimes suckle offspring that are almost as large as themselves. Females never breed more frequently than every other year, and in some areas, the interbirth interval may average more than four years. Although polar bears mate in the late winter, the early embryo undergoes delayed implantation (a phenomenon that seems to be widespread among mammals, especially in carnivores whose food supply is irregular) and gestation does not start until the autumn.

SAQ 19

How could delayed implantation enable female polar bears to adjust reproduction to food supply? How is this adaptation similar to that of reindeer?

Answer

Like the reindeer, female polar bears can adjust their reproduction to the food supply for the particular year and location: fortunate bears may find large, fecund colonies of breeding seals and be able to fatten rapidly by eating several pups a day. Such animals may lay down reserves of nutrients sufficient to raise triplets. Others may produce only one cub, or, if food is really scarce, the pregnancy may be terminated, and the female becomes receptive in the following mating season.