4.2 Aggression

What of the possible disadvantages of living in a group? Think back to the type of interactions between individuals within the groups you saw in the TV programme.

Perhaps the most obvious disadvantage is the increased likelihood of aggression and resulting injury in members of the group. There's also the increased likelihood of spreading disease - parasites or microbial infection spread between the group members. Groups of animals are likely to be easier to spot by predators and I've already touched on the notion of whether group living might decrease the amount of food accessed by some individuals. DA suggests that one of the 'prices to pay' for the disciplined social life of the grey wolf is the restriction on reproduction; recall [p. 134] that only the alpha (i.e. dominant) male and his mate reproduce. Whether such a scheme is disadvantageous to the species as a whole is debatable. Rank positions are not permanent and, as DA explains, young individuals break away to found their own packs. Restricting breeding to prime males and females may in evolutionary terms have been a price for sociability well worth paying.

You'll know from LoM and the programme that serious aggression within groups is generally limited. Lions are often killed by conspecifics, but the victims are not eaten, and violence nearly always stems from the take-over of a group of females by a new male (or coalition of males), or from territorial rivalry between groups. Much of the social behaviour and communication evident in the TV programme is geared towards reducing significant conflict and maintaining social bonds. The development of hierarchies within groups is one such tactic. As you might have surmised from this section, scent-marking helps maintain the hierarchy (recall what was said about social marking). Scent from urine conveys information on social status in the grey wolf; in the African hunting dog, it seems that only the top-ranking individuals scent-mark frequently, so that the 'top dogs' constantly advertise their status to those that are subordinate.

The programme provides examples too of the postures and facial expressions used by social carnivores for communication and to minimise aggression.

Activity 6

Watch the TV programme again from 23.13-28.26, which shows something of the social and hunting strategies of the grey wolf. What signals and body language are used for communication by this carnivore?

Discussion

Howling is essentially a means of establishing claim to and defending a territory. (Despite DA's success on camera (see 23.30) wolves most often howl in chorus, to communicate to a neighbouring rival pack, who are said to respond in similar voice only if they are a match for their neighbours. Scent-marking is also important in territorial defence.) The social rituals before the hunt begins are rich in body language, just as are the greetings as the group reunites. You are likely to have spotted mounting - though not particularly purposive. As DA points out [p. 133], the high tail is an assertive gesture; a lower tail, typically with the ears held back, is displayed by a subordinate when greeting a dominant member of the pack. It's difficult to make out all the communication going on in the playful huddle of pack members in the TV sequence, but mock biting and the occasional lowered head is evident.

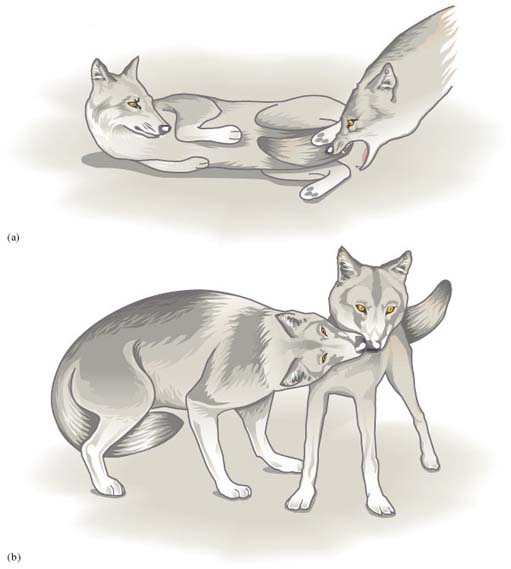

Figure 7 shows two submissive postures in wolves. In (a), the subordinate lies down and exposes the belly, with the tail forward between its legs. Note too that the ears are pulled back. (b) illustrates the 'tail down, ears held back posture' just described. Tail-wagging is evident here; the action may not simply be an expression of canine delight as we might be tempted to believe. Note the crouched posture adopted by the subordinate, with attempts to nuzzle and lick the more dominant pack member.

SAQ 16

Question: What is striking about the origins of these two postures of submission? If you need to, reread LoM pp. 131-134, paying attention to the photographs.

Answer

Both resemble infantile gestures mentioned in LoM. The first is close to what DA describes on p. 132, which promotes the mother's licking (Figure 7b). The second very closely resembles infantile food-begging, as shown in the photograph on p. 134.

An appeasement gesture based on infantile behaviour makes sense, given the likelihood of its evoking parental rather than aggressive responses.

I've spent some time in this section exploring the issue of communication within groups, and looked at the reasons for the development of group living in carnivores. You'll have noticed that there are no simple answers, especially since my approach here has been to do no more than introduce these topics.

Trying to work out functional explanations of what we observe about the lifestyle and behaviour of carnivores is difficult, in part because of the enormous variety on show. The simplest questions - such as 'Why do lions usually live in groups?' - prove difficult to tackle; LoM pp. 151-153 outlines some of the issues. Devising sensible hypotheses is the easier step. What is more difficult is setting up manageable field experiments or observations that offer unequivocal data. In the case of lions, a leading researcher in the field, perplexed by untidy data and the conflicting conjecture currently to hand, draws attention to what he considers a classic paradox of science - 'the more information we have, the less we seem to know'.