5 The primate brain

5.1 The neocortex

Throughout LoM Chapter 9 and the TV programme, DA has referred to the large brain of monkeys and to their intelligence. Humans are the most intelligent of the anthropoid species, but evidence for non-human primate intelligence is growing.

Activity 11

Watch the TV programme from 01.26-09.14 and look back at the notes you made for Activity 8. Take this opportunity to look for examples of the issues raised in the previous section on primate societies. Summarise, in about 200 words, the points made concerning the evolution of the primate brain and the cited incidences of intelligence. You may also find it helpful to reread LoM pp. 248, 251 and 271.

Answer

The evolution of the anthropoid brain is thought to be related to the development of trichromatic vision, as the monkey brain is far larger than the prosimian brain. But other researchers believe that although vision was a contributing factor, it was the complexity of social living that was the main driving force behind the developing brain. Indeed, monkeys today show complex social behaviour, forming alliances to help maintain an alpha male's rank, forming friendships to gain matings or to be accepted into a group, and practising deceit to sneak matings when the alpha male is distracted. They maintain friendships through grooming, both actual and vocal, and infant care. Additional evidence demonstrating monkey intelligence comes from several sources. Rhesus macaques in Japan bathe in hot springs when the temperature falls. Capuchins rub themselves with piper leaves (which release chemicals that act as a natural insect repellent and antiseptic) when mosquitoes and skin infections are prevalent; capuchins have also developed a method for opening clams. Baboons can hunt flamingos. The striking thing about these behaviours is that they have been started by one individual and spread through imitation or direct teaching from one individual to another until the entire population is exhibiting that particular behaviour - so-called cultural transmission, which has its counterpart in many human interactions.

This final section will explore the evidence that scientists have obtained to support the claims that brain size in primates is related to colour vision and group size, and consider why such relationships help us to understand how the subsequent increases in brain size seen in apes and humans may have arisen.

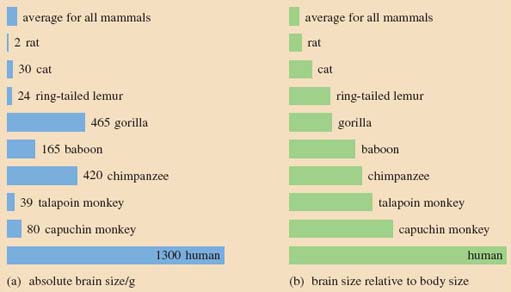

Throughout the class Mammalia (and other vertebrates, for that matter) brain size increases with increasing body size; for instance, an elephant brain weighs approximately 8000 g, whereas a rat brain weighs less than 3 g (Figure 9a).

Question 17

Question: From your previous reading can you suggest some possible reasons for this relationship between brain size and body size?

Answer

The brain maintains all the functions of the body: growth, movement, repair, digestion, breathing, etc., the so-called somatic (relating to the body) processes - as well as learning and memory. As body size increases, animals require a larger brain to support and control these processes.

When scientists take body size into account, however, by calculating the ratio of brain size to body mass for each species (termed relative brain size) some species have larger brains than would be expected from their body sizes. But strikingly, primates have much larger brains for their body size than most other mammals (Figure 9b).

This finding intrigued researchers because brain tissue is known to be metabolically costly. Basal metabolic rate (BMR) is the rate of energy expenditure by an organism at rest at a non-stressful temperature. Scientists have also calculated the cerebral (brain) metabolic rate and shown that whereas other mammals use 2-6% of their BMR on brain maintenance, most primates use 9-14%. The most advanced primates, humans, use a staggering 20%. If the primate brain has evolved to be large in spite of these costs, the increases in brain tissue must confer important advantages.

Question 18

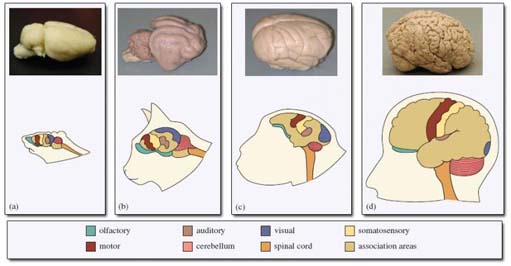

Question: What do you notice from the photographs in Figure 10 about the external appearance of the brain in primate species compared with other mammals?

Answer

The brain of primates is a more rounded shape compared with that of the other mammals. The outer layer of the brain is also more convoluted in primates.

This convoluted appearance is due to folds in a particular region of the brain, the neocortex, a thin layer of cells about 2 mm thick that covers the outer surface of the brain. (Neocortex is the term generally used for the cerebral cortex in primates.) When the ratio of the neocortex volume to the volume of the rest of the brain is compared across the primate order, it is clear that this ratio (termed relative neocortex size, or simply neocortex size) generally increases from the prosimians, through the monkeys to the great apes, and finally to humans. So why is the neocortex so important? You will already know from Section 3 that the evolution of colour vision led to an expansion in the visual cortex, the part of the brain that receives neuronal signals from the retina of each eye. The visual cortex is a region of the neocortex, so expansion in this area will contribute to increasing neocortex size. But colour vision is unlikely to be the only factor influencing the large brain size seen in primates; colour vision has evolved independently in fish, birds and amphibians, which do not have comparably large brains for their body sizes. Other regions of the neocortex receive input from other senses (Figure 10), such as an auditory (hearing) area, and a large part of the neocortex is involved in controlling movement of the body, i.e. motor control. The remaining parts of the neocortex are termed association areas, areas that are involved in higher thought processes, memory or creative thinking.

Question 19

Question: What is the most striking difference between the neocortices of the four species shown in Figure 10?

Answer

As the total size of the neocortex increases from rat to cat, through monkey to human, the association areas show a greater increase in size than the sensory and motor areas. This disproportionate change is interpreted as meaning that the major increase in primate brain size compared with other mammals is related to 'creative thinking'.