Employee engagement

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 26 April 2024, 6:33 PM

Employee engagement

Introduction

Engagement is one of the key buzzwords in 21st century management. The strategic human resources management (SHRM) approach is founded on the belief that people are the key differentiators in achieving competitive advantage. Employees need to be managed skilfully and seen as assets to be developed rather than costs to be controlled.

Employee engagement is therefore central to the ideology and practice of SHRM. But what does it mean to be engaged in work? How can engagement be encouraged? How does the reality of working conditions affect these attempts? To what extent does the structure of management and ownership in organisations affect the prospects of employee engagement?

In this free course we explore these questions though three key themes:

- the concept of employee engagement

- employee involvement and participation

- collective aspects of employee relations.

We shall also examine how the wider context of employment relationship affects how engagement is understood and the methods used to encourage it.

In this free course, we define engagement as ‘a set of positive attitudes and behaviours enabling high job performance of a kind which is in tune with the organisation’s mission’.

Employee engagement is therefore vital to the success of organisations. Engaged employees are likely to be more satisfied, committed and productive in their work. In economies increasingly dominated by service industries, good customer relations – built by engaged employees – are central to success.

This free course works by building on your own experiences as employees and managers of different kinds of organisations. The organisation for which you work and those with whom you come into contact all make choices as to how they engage with their workforce. These choices raise all kinds of dilemmas and this free course aims to make you aware of these. It will also equip you with knowledge if you have to make these choices for yourself.

We shall see in this free course that strategies for and experiences of employee engagement differ. These differences are strongly influenced by contextual factors like organisational and industry norms and the wider environment of employee relations.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course BB845 Strategic human resource management.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

identify and describe the meaning of employee engagement and its different components

appreciate the strategic issues associated with employee engagement

describe the changes in systems of employee relations

appreciate the impact of structures of management and ownership on employee engagement

reflect on the current state of employee engagement in an organisation.

1 Experiencing engagement

Most people who have worked in different jobs in different sectors will have different experiences of employee engagement. Moreover, as we progress in our career and our lives change, we often find our own expectations about how we want to engage in our work also change. It is certainly not possible to identify a single set of assumptions and practices about employee engagement that is universally applicable.

We want to begin therefore with a set of activities that encourages you to reflect on your own experience of employee engagement.

Activity 1.1 Experiencing engagement

Activity 1

Introduction

Purpose: to reflect on your own working experiences.

Before we unpick different aspects of employee engagement as it is understood and practised within SHRM we want to begin by identifying your own experiences at work which might be relevant to these ideas.

Task A

We would like you to think about the different jobs you have had in your career so far. Think about the following questions with reference to one of those jobs.

- Which aspects of the job did you like and dislike and how did these change during your time of employment?

- Which aspects of the job kept you engaged? Think of the different factors which were relevant to your level of engagement. Did you enjoy the work itself? Were you more motivated by the rewards you received for the work? Were you committed to the organisation?

- Did your engagement with the work change over your period of employment? If so, what caused these changes?

- If you are no longer in this job, what was it that influenced your decision to leave the organisation? You might think about the respective importance of ‘push’ (related to the job you are leaving) and ‘pull’ (related to the new job) factors in this decision.

In answering these questions, begin by contextualising the nature of the organisation and type of work. Explain what (if anything) kept you engaged with the work, whether and how this changed through the course of your employment and what influenced your decision to leave. Was there anything the organisation could have done differently to change your experience of the job?

It is important that for this and all other activities in this free course you make notes and prepare a short statement capturing these issues.

Task B

Now read the article ‘The time of your life’ which presents some recent research on the dynamics of employee engagement in the working population of the UK. It suggests that engagement is strongly influenced by such factors as the life stage and size of companies. While reading, make some notes and consider the question: to what extent does this reflect your experience?

The time of your life

Brown, A., Roddan, M., Jordan S. and Nilsson, L. (2007) ‘The time of your life’ People Management, vol. 13, no. 15, pp. 40–3.

Are your staff young and promiscuous, steady and driven or content and loyal? Finding out could reveal the best way to keep them motivated.

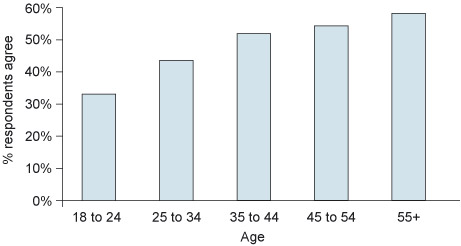

Older workers may be more expensive, but engagement and motivation increase with age and employees aged 55 and over tend to be happier with their work and more likely to stay with their employers.

Findings from the 2007 YouGov PeopleIndex employee engagement study reveal three distinct stages of the work-life cycle: “young and promiscuous”, “steady and driven” and “content and loyal”. These different phases have important implications for UK companies and suggest employers should consider approaching employee engagement in a segmented way, according to life phase.

Turnover, for instance, is likely to be high among younger staff, which makes it all the more important to engage them right from the start and offer great career development so they are committed and motivated to perform for however long they stay.

The survey of 40,000 employees from a broad range of industries across the UK, conducted earlier this year, shows that, in general, only 52 per cent of employees are engaged in their organisation, less than three-fifths (57 per cent) would speak highly about their company as an employer, and only two-thirds (67 per cent) are motivated to perform well in their job.

Loyalty is also a key challenge for today’s companies. Gone are the days when young people joined a firm and stayed for the long term. Employees with 10, 20 or even 30 years of service in the same company tend to be the exception rather than the rule.

Less than two-thirds (64 per cent) say they feel loyal towards their company. Only three-fifths (61 per cent) would want to be with their firm in a year’s time, and this falls to less than half (48 per cent) in three years and less than a third (31 per cent) in 10 years’ time.

Moreover, when comparing strongly engaged employees with strongly disengaged employees in the UK, the strongly engaged are almost 25 times more likely to have strong loyalty towards their organisation, more than five times more likely to feel motivated to perform, almost four times more likely to speak highly of a company’s products, services or brands, and almost three times as likely to believe the company is customer-focused.

However, these statistics vary markedly between the three stages of the engagement life cycle. The young and promiscuous (aged 18-24) demonstrate the lowest levels of engagement (48 per cent), motivation (65 per cent), job satisfaction (59 per cent) and commitment (60 per cent). This is not surprising when you consider that this group has grown up in a period where it is not unusual to move between jogs in quick succession, and, indeed, it can be the quickest way to get ahead.

This group can be daunted by the prospect of commitment to an organisation, even in the short-to mid-term, and three years – a relatively short period of time within a person’s entire career – is seen as considerably longer in their eyes. Only half (52 per cent) say they want to be with their organisation in a years time, and a third (33 per cent) in three years’ time.

UK organisations need to ask themselves: is high turnover among this age group inevitable, or can something be done?

Note, however, that the young and promiscuous have the highest satisfaction rating in terms of training opportunities (52 per cent) and are the most satisfied group in terms of career development (45 per cent), although these career opportunities could be perceived as external by making a move elsewhere, rather than internal within the current organisation.

It therefore becomes important for organisations to marry training with the perception of internal opportunities. To maximise long-term loyalty and engagement, young employees should be given the opportunity to apply their new skills and take on more responsibility. Internal promotion opportunities need to be communicated effectively and recognised and rewarded accordingly.

At the next stage – the steady and driven period, which covers the 30 years between the ages of 25 and 54 – the study suggests people tend to have found their main career interest and are striving to get ahead. Engagement tends to remain steady during this period, scoring around 51 per cent. Similar patterns are seen in satisfaction, motivation, commitment and loyalty.

Just over three-fifths of the steady and driven report that they feel loyal towards their organisation, but there are differences between the younger and older members of this group when it comes to actual loyal behaviour. For the younger members, moving jobs after a reasonably sort period is de rigueur, whereas staying with a company for over three years becomes more acceptable with age.

As employees hit the content and loyal period (55 plus), they are at their happiest in terms of working life. People have progressed to a level they are content with, or are resigned to the fact they may not go further, and so are less focused on getting ahead. The highest levels of engagement can be seen during this stage, at 59 per cent (compared with a UK average of 52 per cent), and this group tends to be the most satisfied in terms of reward and recognition. Not surprisingly, they are the most loyal, with 58 per cent of this age group saying they want to be with their organisation in three years’ time.

There are also big differences in engagement between large and small companies. It is easier to feel part of the team and that you are making a real difference if you are an employee in a small company of less than 100 people. You are closer to senior management and hence the strategic vision of the organisation.

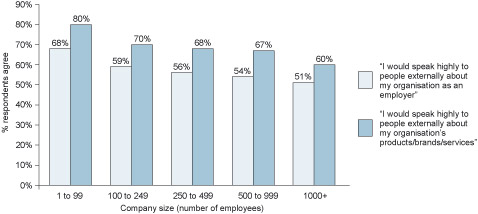

High levels of pride in the organisation (70 per cent against a UK average of 64 per cent) are seen among employees in small firms, who are much more likely to recommend their organisation as a good employer (68 per cent compared with a 57 per cent average) and the products and services they offer (80 per cent against 67 per cent). These ratings all drop off as company size increases.

In fact, a comparison with larger companies, small firms are rated highly by their employees for communication, line management, reward, recognition, senior leadership and training.

Three-quarters (75 per cent) of staff in small firms say they feel loyal to their organisation, and almost two-thirds (65 per cent) say the organisation deserves their loyalty. Compare this with companies with 1,000 and more employees, where loyalty falls to only 59 per cent and less than half (44 per cent) say their loyalty is deserved.

The result is that employees in small companies are more engaged. This presents a big challenge to both large organisations and those that are taking the next steps in growing from small – to medium-sized and beyond.

For large companies, the task of engaging employees in the organisation is inherently more difficult. It therefore becomes more important to identify and monitor the factors that specifically drive engagement for their employees. It is too easy to feel like a ‘small cog in a big wheel’, but we find that the large organisations that manage to make their staff feel like they are part of the fold and that they are making a real difference reap the rewards in terms of individual and team productivity.

Expanding companies should take stock of how they can continue to drive engagement by maintaining the factors that have helped them to be so successful as a small company. Maintaining a small, family atmosphere for as long as possible and continuous, effective communication is vital to making employees feel they are valued and recognised. This can be encouraged through smaller teamworking models and strong two-way communication mechanisms. It is also important to ensure that good quality processes are in place for the next stage of the company’s life.

What drives engagement?

Employee engagement is an individual’s connectivity to an organisation. It is made up of both their emotional and rational attachment to the company, its work and its performance. Employee satisfaction is, as the HR community recognises, no longer enough, it is engagement that is critical to aligning people with our strategy.

Research has shown there is a strong link between employee engagement, and harder organisational metrics such as customer service, productivity and financial performance. The best organisations understand these links and are focused on identifying the factors that will drive stronger engagement levels among their employees.

The 2007 YouGov PeopleIndex employee engagement study suggests that there are a number of core factors driving employee engagement. These hold true across organisations in different sectors, large and smaller companies and at various stages of the employee life cycle.

1 Recognition: do managers and the company as a whole make people feel valued by telling them when they have done a great job and celebrating their successes?

2 Reward: are people fairly rewarded for their efforts and do they see the effort-reward balance as a two-way street?

3 Change management: how well do companies communicate about change (and the rationale for it) and how well do they engage employees throughout the company in the change process?

4 Performance management: how well do organisations deal with poor performance and how good are they at rewarding great performance differentially?

5 Leadership: how well do senior executives in the organisation outline the vision and strategy for the company, communicate and engage their people with it and lead by example in terms of the behaviour and values needed to deliver the vision?

‘The best firms are focused on identifying the factors that drive engagement’

The study suggests that it is many of the softer, people-based skills that are lacking in UK organisations: the factors about are all ones that the data shows have a high impact on employee engagement levels but that, at present, are given low ratings by the typical employee. The challenges of effective leadership, effective management and getting the balance of reward and recognition right remain the key issues for companies wishing to raise their engagement levels.

Andy Brown is managing director, Matt Roddan associate director, Sarah Jordan senior analyst and Louise Nilsson analyst in the organisational consulting group at YouGov, an online research and consultancy agency.

Task C

Finally, watch this short video. We shall see in later sections of this free course that employee engagement is big business for management consultants. In this video we see one such consultant, Will Marre, outline his reasons for its contemporary importance. He summarises what he considers the different levels of employee engagement and proposes what he believes to be the most important factor in contemporary work affecting these levels. While watching, consider the following and make some notes:

- To what extent does this reflect your experience?

- What is his central argument?

- Do you share his view?

If you are reading this course as an ebook, you can access this video here: The future of work and employee engagement - Will Marre

Discussion

Most people find that their level of engagement with their work is far from consistent. There are many factors that can affect this. It is not simply moving to a different job that creates change. Changes to personal circumstances can also affect our attitudes. Management and organisational practices are extremely influential too and often dictate how work is carried out and experienced. External factors are very important and shape the context for work. What is nominally the same job will actually change from year to year.

All of these factors will influence how we engage with our work. Intrinsic and extrinsic influences are also important. For example, we might engage with a job which is intrinsically unstimulating because of the rewards that it provides. Some work is valued because of the wider social contribution that it makes. This, according to Will Marre, is an increasingly important explanation for engagement.

2 Finding meaning and engagement in work

You will no doubt have found from the previous section that most people who have worked in different jobs in different sectors will have different experiences of employee engagement. Moreover, as we progress in our career and our lives change, we often find our own expectations about how we want to engage in our work also change. It is certainly not possible to identify a single set of assumptions and practices about employee engagement that are universally applicable.

No doubt there are a number of issues which keep you engaged in your job. It is likely that financial reward is an important factor. The nature of the work itself is significant, as are social factors derived from the people with whom you are working. You might identify with the organisation that you are working for and wish to contribute to its objectives. You might have professional attachments that are more important than organisational identifications or, conversely, you may work in an area for particular personal or family reasons. There is a strong diversity of reasons why people engage with their jobs.

People bring meaning to and take meaning from their work. We might consider how our individual identities are influenced by our work. For example, we often ask, when introduced to someone for the first time, ‘What do you do?’ Why do we ask this? What conclusions do we draw from the answer?

Clearly for many work is more than a means of simply paying the bills, it takes a major role in making them who they are. On the other hand, we must also recognise that for some people work offers only toil and drudgery and can produce both physical and mental pain.

It is because of this diversity of purpose that building employee engagement is problematic. Managers must make strategic choices about how to engage employees in the hope of winning their commitment and encouraging them to expend discretionary effort in their work. But it is important to recognise that any such interventions will depend on an understanding of the meanings that people bring to, and derive from, their work. These meanings are unlikely to be fixed but they represent the reasons why and how people work, and the consequences of their work for their sense of self-identity. The relationship that individuals have with their work is likely to change as their circumstances change.

It is naïve to consider engagement independently from this context. We must recognise that the nature of employment and the different relationships that individuals have with their work are central to understanding, and influencing, their engagement with this work.

In the following set of activities we consider the different meanings that individuals can derive from work.

Activity 1.2 The meaning of work

Activity 2

Introduction

Purpose: to consider the different meanings that individuals can derive from work.

Task A

Read the following short extract from Alain de Botton’s book, The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work.

The pleasures and sorrows of work

De Botton, A. in Henley, J (2009) ‘The new work order’ The Guardian, 24 March.

[ … ]

Nowadays workers have to be ‘motivated’, meaning they have – more or less – to like their work. So long as workers had only to retrieve stray ears of corn from the threshing-room floor or heave quarried stones up a slope, they could be struck hard and often, with impunity and benefit. But the rules had to be rewritten with the emergence of tasks whose adequate performance required their protagonists to be, to a significant degree, content, rather than simply terrified or resigned. Once it became evident that someone who was expected to draw up legal documents or sell insurance with convincing energy could not be sullen or resentful, the mental wellbeing of employees began to be a supreme object of managerial concern.

The new figures of authority must involve themselves with childcare centres and, at monthly get-togethers, animatedly ask their subordinates how they are enjoying their jobs so far. Responsible for wrapping the iron fist of authority in a velvet glove is, of course, the human resources department. Thanks to these unusual bodies, many offices now have in place a zero-tolerance policy towards bullying, a hotline for distressed employees, forums in which complaints may be lodged against colleagues and (I know of one office) tactful procedures by which managers can let a team member know his breath smells.

Contrived as these rituals may seem, it is the very artificiality that guarantees their success, for the laboured tone of group exercises and away-day seminars allows workers to protest that they have nothing whatsoever to learn from submitting to such disciplines. Then, like guests at a house party who at first mock their host’s suggestion of a round of Pictionary, they may be surprised to find themselves, as the game gets under way, able to channel their hostilities, identify their affections and escape the agony of insincere chatter. Power has not disappeared entirely in modern offices; it has merely been reconfigured. It has become ‘matey’. It is by posing as regular employees that executives stand their best chances of preserving their seniority.

[ … ]

Though we think of the point of work as being primarily about money, these dark economic times only emphasise the extent to which generating money is an excuse to do other things, to rise from bed in the morning, to talk authoritatively in front of overhead projectors, to plug in laptops in hotel rooms and to chat in the office kitchen. Long before we ever earned any money, we were aware of the necessity of keeping busy: we knew the satisfaction of stacking bricks, pouring water into and out of containers and moving sand from one pit to another, untroubled by the greater purpose of our actions. To view our upcoming meetings as being of overwhelming significance, to make our way through conference agendas marked ‘11 a.m. to 11.15 a.m.: coffee break’ and not think too much about the wider purpose – maybe all of this, in the end, is the particular wisdom of the office.

Office work distracts us, it focuses our immeasurable anxieties on a few relatively small-scale and achievable goals, it gives us a sense of mastery, it makes us respectably tired, it puts food on the table. It keeps us out of greater trouble.

Task B

Now watch the following video where de Botton expands on his ideas about the role of work in society.

If you are reading this course as an ebook, you can access this video here: Why do we have HR departments?: Alain de Botton

Having watched the clip, reflect on the following questions:

- What are de Botton’s key points about changes in societal attitudes to work over time?

- Do you agree with his suggestions about the importance of work today?

- What do you think about his argument that work provides a necessary distraction from the rest of life?

Task C

As we have seen, de Botton provides a wryly cynical account of the modern workplace. However, it is worth reminding ourselves that for many work remains hard physical labour suffered through economic necessity as we see in the following documentary.

Watch the next film, where workers in France account for their experiences in the car, food, fishery and electronics industries. What do you think it means to be ‘engaged’ with work in these environments? Note that this clip is in French with English subtitles.

Transcript: Part 1

(All in French with subtitles)

It’s hard to talk about a job that you can’t stand anymore.

I can assure you.

It gets really cold, really damp.

The boxes just get heavier to carry. The pace is unbearable.

We work because we need food on our plates to survive

So I think this kind of work should be exposed to the world

Because it’s really no joke

Christophe, 51 Fishing Port since 1978

I don’t think people know much about the fish industry. We often talk about the meat industry. But to talk about the fish industry seems a bit taboo.

Our bosses have always forbidden us to talk about it. Because our working conditions are so hard.

We have to cut the fish, process it, put it through different machines.

It’s really like an anthill, people rushing all over the place.

You process fish as fast as you can because of the lorries

The lorries have deadlines. We send our fish across Europe.

So sometimes we work non-stop for five or six hours . . . sometimes six and a half.

And if we don’t go fast enough they tell us to go faster because of the lorries.

Before there was a good atmosphere in the fishing port. Despite the work.

But the atmosphere, as in other sectors, has changed completely.

Now you really have to speed up. There’s much more pressure.

Vincent, 42 Meat industry since 1989

My particular job is preparing ham.

I cut off the fat and take out the bone for 7 or 8 hours every day.

It takes about a minute to de-bone the primary part of the ham.

We have a break every 2 hours.

That means we work non-stop for 2 full hours.

Over a day this leaves us with very little time to rest our muscles.

The production rate is really beyond human capacity.

A quality ham product normally requires 2 minutes work.

But it has come to a point where we have to do it in under a minute.

Francoise, 42 car industry since 1989

I work in the car industry

My job is to fit in dashboards near the gearbox and other interior furnishings.

After that I put in the back seats.

And all of this has to be done in under a minute.

And that’s really hard to manage.

You hardly have time to finish one car before the next one comes along.

Production rate is all that matters. Here is an example.

I remember being on the assembly line and never having time to raise my head.

I would spend the entire day with my head in the boot of a car.

Not a second to rest or even look around me.

Not even the time to grab your water bottle to drink.

They say we’re wasting time. You can’t imagine how bad it is.

Monique, 62 electronics industry from 1968 to 2004

To assemble a television you have the box and of course the circuit board.

So my job was to place components on the board.

This was all done on an assembly line.

We worked one after the next in a line.

And what we did was to take one component after the other. All day long like this.

We’d place about sixty components a minute.

This would vary according to the size of the component and its manipulation

And that’s how televisions are made.

When I started in the factory in ’68 there were almost 3000 workers.

When I retired in 2004 there were about 1050 workers left

But with an increasing production rate.

Because when I started it took several hours to produce a television.

When I finished, the production rate was down to 15 minutes.

Of course the meantime machines had been introduced.

But all the same the workers had to follow the faster pace.

So with 3 times less workers we now produce over 3 times more televisions.

So each component is places in less than a second.

You can't imagine how fast it goes.

Francoise, 42 car industry since 1989

We start at precisely 5.39 am.

Our first break is at 7:39 and it ends at 7:50.

Our second break is from 9:45 to 9:50. The third is from 11:30 to 11:35

Our main lunch break lasts 11 minutes plus 2 5-minute breaks later.

With such little time you can forget about eating a big sandwich.

Because that’s the only time you can go to the toilet

Then you wash your hands, run back to swallow the rest of your sandwich.

There’s hardly any time to eat properly.

This means you can't really chew your food.

Consequently a lot of colleagues take digestive tablets for gastric problems.

I often hear about people with ulcers, which develop into cancers sometimes.

For some it’s fatal.

We regularly hear of colon, intestine and stomach cancers

Even I sometimes feel my digestion isn't working properly and get stomach aches.

You can't possibly do everything in 11 minutes.

They say it complies with the work regulations. I say it’s inhuman.

Marie, 57 Fishing port since 1971

When I started in the fishing port over 30 years ago even though the days were longer, we didn’t feel as tired as we do now.

The atmosphere was much better. The production rate wasn’t at all the same.

In those days, there was a family atmosphere.

We were all working together.

Then, there was much more mutual respect.

Now we hardly talk to each other

Now it’s all about productivity.

And the day we have to work faster, they don’t even ask us nicely.

Monique, 62 electronics industry from 1968 to 2004

It’s true that 30 years ago going to work was quite pleasant.

Despite the hard work we could still laugh and enjoy each other’s company.

During my last 10 years in the job it all became much harder.

Everything had to become more profitable

Our factory was privatised which meant shareholders.

Without wishing to go into politics, shareholders demand a maximum return.

To get a maximum return means maximum productivity.

Even if new equipment made certain jobs easier.

That wasn’t the case everywhere

So the change in atmosphere comes down to profitability and nothing else.

Vincent, 42 Meat industry since 1989

We have to stand at our work stations. We can't move.

We stamp our feet because our working space is only a meter wide

So obviously people have blood circulation problems in their legs.

And so we asked if they could buy seat supports

That is a padded seat that people could rest on while standing.

Unfortunately our request was rejected.

But that didn’t stop them buying a €3,000,000 machine to increase productivity.

Christophe, 51 Fishing Port since 1978

We don’t have the right to complain about our backaches or the cold.

In the winter it gets really cold. All we can think of is to rush home and restore our body heat

Sometimes the water freezes in the pipes

And we’ve no running water to fill the tanks.

So you can imagine our working temperature if the water has frozen.

All day long we handle fish which is surrounded by ice

Our fingers often get numb so we put them in buckets of warm water.

But the bosses don’t like that because we’re wasting time.

But when you’ve got frozen fingers you don’t have the choice. So we hide it.

Marie, 57 Fishing port since 1971

We only have plastic gloves.

And when it gets cold those with circulation problems suffer most.

The blood vessels burst, the fingers turn purple, swell up and you can't bend them.

Some get chilblains on their hands, which begin to fester.

Nowadays all this seems unbelievable.

When you go to the fishmongers and see the display it’s hard to imagine what that lies behind it all.

There’s just so much suffering.

We have to cope with so many harmful problems.

We’ve got health problems … and lots of others

Vincent, 42 Meat industry since 1989

I work in the meat-cutting sector.

For reasons of hygiene the temperature must be between 4 and 6 degrees.

But the humidity level remains around 60%

These two constraints together with the fast production rate mean that we end up sweating heavily in a cold, damp atmosphere.

So, either you get used to it because your body compensates

Or you don’t get used to it and you're ill all the time.

Under these circumstances the slightest little bug spreads around easily

Henri, 63 food industry from 1973 to 2004

Some jobs were really tough.

For example handling heavy weights.

You had to lift the pastry out when there was a machine fault.

That was tough.

In the oven room it obviously got quite hot.

Once the biscuits were cooked you had to pick out the defective ones in order to avoid any problems further up the line.

You stored them in bags to be moved when you had the time.

All this time the biscuits would be letting off heat.

Unfortunately most of this would occur during the summer.

That doubled our distress. The heat outside prevented the heat inside from escaping.

In summer the temperature in the oven room was often over 40 degrees.

Consequently we were allowed to leave the oven room for 10 minutes every hour to drink and cool down our body temperature.

That’s still 50 minutes in extreme heat.

Monique, 62 electronics industry from 1968 to 2004

It wasn’t too bad during the winter.

The temperature in the factory was around 19 degrees. It was fine.

The real problem was the summer.

I remember it going over 38 degrees.

Working so quickly in such heat is unbearable.

You can't properly handle components with sweaty fingers so you drop them.

At the end of a hot day it was impossible to finish the required quota of circuits.

Of course when it got too hot the machines were stopped and allowed to cool down.

That’s normal because electronic machines can overheat at 38 degrees.

So the machines were allowed to stop but we could only stop for 5 minutes every hour.

That was at 38 degrees.

But often the machines were stopped before that.

Good for them. This way they’ll avoid RSI!

(RSI Repetitive Strain Injury)

Francoise, 42 car industry since 1989

I have to press in the dashboard with my thumbs. There are no machines to do it for me.

I position it near to the gear stick and hand brake.

Of course our joints really hurt.

We suffer from tendonitis, shoulder pains backaches.

We’re really broken in two.

Sadly some are afraid to stop leading to permanent damage.

I remember a colleague of mine she let things get so bad she can’t use her hands anymore.

She’s now disabled with carpal tunnel syndrome.

So a big thanks to the company. She’s lost the use of her hand for good.

It’s absolutely tragic.

Monique, 62 electronics industry from 1968 to 2004

Every single person who has worked on our assembly line suffers from RSI.

Whether it’s the elbow, the shoulder or the wrist, it’s inevitable.

Those inserting components on the line sit leaning forward like this al day.

This awkward position obviously causes serious neck and back pains.

So when someone has to work and can't move their head and upper body they suffer excruciating pain. Worse than for an elbow or a shoulder joint which is already pretty bad.

Marie, 57 Fishing port since 1971

I'm involved with handling and packaging.

So according to the orders we adapt the box sizes

If it is hake it will be a small box.

We also cut up large fish, which can weigh up to 7 or 8 kilos. You should see the huge knives we use.

So it’s the shoulders and wrists that take the strain.

It’s just so tough on the joints it wears you out

Christophe, 51 Fishing Port since 1978

In our job so many people get ill and stop before retirement.

I can tell you there aren't many retirement parties.

People often go on sick leave long before they retire.

Standing at a table with a knife in your hand for 40 years.

Many began when they were 14 or 15 and have to give up before the end.

I haven't seen many able to retire properly.

I can't see the next generation working 40 years like that. In any case a youngster starting at 20 will have serious back damage at 30. And that’s being optimistic!

Jacques, 55 electric cabling since 1971

I used to lay electrical power cables and have to climb up pylons and that’s where all my troubles started.

We had to climb up pylons between 12 and 14 metres high.

Every single day!

Sometimes we did 14 each in a day.

It’s when the first symptoms appear that you look back over the past.

Living with that in mind is unbearable.

My arthritis started simply through the repeated movements. The weights we had to carry on our backs.

Dragging electric posts across fields.

But worst of all was pulling the huge cables. Because then all the strain was on your knees and joints. It was disastrous.

I did that for years. With my colleagues of course.

This resulted in tendonitis in my elbows and wrists. And frequent finger cramps.

It’s not surprising because I always had to grip things hard.

And so it just went on and on and on

Transcript: Part 2

(All in French with subtitles)

Monique, 62 electronics industry from 1968 to 2004

Because of the damage I have suffered I can no longer open this shutter.

My shoulder and elbow hurt too much so I avoid lowering it. Though sometimes I have to just to let in the sunlight.

My shoulder injury means I have to use this ladder to reach for a glass.

Before I could raise my arm like anybody else. Now I can't.

This ladder’s never very far.

Once I'm on the first step I'm high enough to get a glass.

I don’t have to do this every day but it’s the only way to reach for a glass.

Whether a glass, a pan or anything else if it’s high up I have to use a ladder.

For example I do a lot of ironing and that’s become far too painful. Especially the elbow and the shoulder

To limit the pain in my shoulder I have to make small movements.

Ironing trousers isn't easy.

Soon I’ll have to get someone to do it because it hurts too much.

The factory management refuse to acknowledge this suffering.

Because if they do accept it they would have to adapt the factory.

Work doctors try their best but they can't do very much either.

We need jobs that take into account people’s disabilities.

Vincent, 42 Meat industry since 1989

Among my own colleagues a lot have already been operated on.

Wrists, elbows and as high as the shoulder

Recently some were even sacked because of their disability

Since our company is based on manual work as soon as a worker can’t keep up they throw him out.

That happens in 8 out of 10 cases.

As a result we find workers around 40 who are unemployed and have hardly a chance of finding a new job because of their poor physical condition.

People become like faulty products and are rejected.

To have reached this point is very sad.

Jacques, 55 electric cabling since 1971

It all began in 2005

I was laid off by the doctor for a month.

Then I went back to see him and said I was a bit better

Back at work for 3 or 4 days and “bang” it all started again.

I had to stop for a month. And stop again after 2 weeks

In the end they called me in.

They said, “We can't put up with your unpredictable moods any more.”

They told me it was better to stop than to carry on. But I really wanted to carry on.

So I made the effort. I felt I had to. I lasted almost a year.

But it damaged me even more.

And what did I get out of this? Nothing but a broken body.

Henri, 63 food industry from 1973 to 2004

Whenever we discussed working conditions it was hard to agree.

A lot of workers said: “If I lose my job how am I going to eat?”

And it’s true even today that people prefer to hide bad working conditions rather than be told by their boss to look for another job.

Let’s not forget that employment is under so much pressure these days that people say, “better keep my mouth shut today than lose my job tomorrow.”

Vincent, 42 Meat industry since 1989

In my factory very few people have been able to enjoy their retirement

In the last 5 years or so 10 or 12 people have retired. Only 3 of those people are still alive

Working conditions before were perhaps very tough

But I think today’s working conditions are more harmful physically.

Particularly the production rate.

Francoise, 42 car industry since 1989

As soon as you want to make more cars with less people, someone has to suffer.

I won't even start to count the number of worn out workers. And I've noticed when people retire their life expectancy is very poor.

I often hear some die 2 or 3 years into retirement.

I don’t know if it’s due to working conditions but they die early.

There’s no doubt our life expectancy is less. Not surprising if you look at how we work.

My work was fitting pipes at the shipyard.

I spent most of my time in the engine room.

My pipes would carry lubricants or diesel as well as water or wastage

And of course sea water to cool the engines and provide ballast.

All this goes through pipes and that was my job.

I was able to retire early under the Asbestos Agreement

There are over 2000 shipyard workers in the same case as me

In the shipyard asbestos was totally banned in 1997. Before then we worked with asbestos every day in the engine room.

All the steam pipes were covered with asbestos to keep the heat in.

These pipes were 25 or 30 mm thick.

The insulators used to come to cover the pipes and as they cut the asbestos we were right next to them.

Breathing in air full of asbestos dust

And for the big pipes we worked asbestos ourselves

The workshop sent us asbestos sheets that we cut up for joints

So we were really in close contact with asbestos

A normal asbestos joint with its protective covering isn’t dangerous

It’s got an oil-based covering that makes it safe

But as soon as you start drilling or cutting it the asbestos dust flies off.

It’s so small you can't see it

One of my best mates died from asbestos at 57

He’d only been retired for 2 years when it hit him

Sometimes it spreads very quickly and sometimes it can be quite slow

There are so many people with asbestos in their lungs

Little by little they’ll have difficulty breathing.

Then it grows into wide spread cancer leading to certain death

Jacques, 55 electric cabling since 1971

After all these years I haven't seen any progress

I've been doing the same job for 38 years and nothing’s changed

Nothing at all

Every morning we reach the site put on our harness and up we go

It’s always been like that

And today it’s got even worse because of the new cables we have to install

They're much heavier and more difficult to work with

It takes two of us to lift them. I don’t know how we manage. Pure madness!

Christophe, 51 Fishing Port since 1978

We watch the years pass and there’s still no improvement

We still don’t have any lifting equipment. It’s all done by hand

On the contrary things have got worse

Before on the port we had weight limitations on the boxes

It used to be 50 kilos. We got it down to 40 and then 30 kilo boxes

But now we receive boxes from all over Europe so we have to adapt to their standards handling boxes up to 70 kilos

Ten years ago when Europe required white factories, everything became white

That was it. Nothing changed except the colour. The working conditions certainly didn’t.

Francoise, 42 car industry since 1989

Before work was more relaxed but now that’s over

As I said we don’t have time to look up or look around or even talk. Just keep your head down inside the car

That’s how bad things have become

On top of this they’ve increased car production without adding any extra workers

Which leaves us without a second to rest

That’s what happened on the line recently. It’s a nightmare

Vincent, 42 Meat industry since 1989

We used to be 1000 employees. In the last two years we’ve lost 250

About 30% of those felt they had to quit

This certainly suited the bosses

Since with the same amount of production and less workers, productivity went up

Where there used to be 4 on a job now there’s 3

The worst case is 3 workers down to 1, producing the same amount

So he’s tripled his work rate

Until the day he drops then they’ll throw him out and start again

Sadly it’s always the workers at the bottom of the ladder who ruin their health

Francoise, 42 car industry since 1989

We often feel we’ve ended up becoming robots

We function but we’re not supposed to think or even exist

We survive without consideration. It’s awful when you think of it

There really seems to be a loss of human dignity

Workers feel their sacrifices aren't appreciated by the company

Sure at Christmas they’ll get a box of chocolates or a toy car

It’s pathetic and some workers say so

But they’ll never give us any financial reward

In France we might have the highest productivity rate but the human cost is enormous

As I'm talking about this I really feel overcome with emotion

It hurts me when I think how badly we’re treated

Marie, 57 Fishing port since 1971

The bosses often say they are the company. But I think it’s also the workers

Whatever they might say doesn’t help us in any way. There's just no progress.

And no one ever thanks us for a hard day’s work

Even when we’ve given everything they’ll never say a word or even smile

And for me that counts

So can anybody tell me what physical distress at work is?

Our job isn't classified as causing physical distress. So which ones are?

That’s why we tell youngsters to study hard or they’ll finish up in the fishing port

We don’t want our children to end up like us

Even if it’s a job that’s helped our families survive, it’s just not acceptable

Christophe, 51 Fishing Port since 1978

When I first sat down here I thought I'd tell a happy story of the fishing port

Because my family has worked in this fishing port for generations.

My great grandmother sold the fish that my great grandfather had caught

My whole life’s been here. I really wanted to talk about the good times

I remember my grandfather back from sea, my grandmother selling the fish from her cart

But those times are gone. Now we are just oppressed.

It’s hard to admit we've become exploited

The job itself is wonderful but certainly not under these conditions

Now we’re sick of it

Look at me. I'm worn out. I'm 51 but I feel 65

I don’t know what its like to be 65 but I feel I'm already there

My back’s seriously damaged and so is my mind

A lot of us suffer from depression, anxiety and stress. It’s terrible

Because the work and the effort is too hard

Of course we all know fish is good for your health

But not for our health

Jacques, 55 electric cabling since 1971

I've got to the point today where I'm a complete wreck

I've done 40 years hard labour just to end up like this.

And I can't retire yet. I'm only 55

So what does the future hold after all my pain? What’s left?

I can't run. I can't do any sports. I can still just about walk but not very far

I can't do what I used to. Now I have to see the future differently

A few years ago I had lots of plan for retirement. They’ve all fallen apart

Suddenly it’s all over. No hope. I'm in such a state I can't do anything.

And I'm not the only one

Employers must realise that manual workers will always be needed

We can always replace machines but we can never replace human beings

Even if you're tired and worn out you shouldn’t be replaced

How often have we heard people say “Pain comes with the job”

Nonsense. Pain shouldn’t have to be part of the job. But people accept it

I finished up with epicondylitis a major elbow injury and a shoulder injury, which involved cutting a tendon and repairing another

Work is fulfilling but not if it means destroying your health

It’s a shame to see that the bosses don’t care at all. And that’s unacceptable

That was true 40 years ago and it’s even more so today

Working yes. Destroying our health no. Bosses not caring, no.

This was their work: their sorrow.

“Christophe”

“Vincent”

“Francoise”

“Marie”

“Jacques”

Monique Bobeche

Henri Chevolleau

Joseph Rocher

To whom we are sincerely grateful

As well as:

Yvonne Boulic

Olga Tharaud

The Board of Directors of ISSTO

[Institut des sciences sociales du travail de l'ouest]

and

Gwenola Billon

The Regional Directorate of Brittany for Work

Employment and Career Training

The Committees of the CTGFO

CGT and CFDT for the regions of Brittany

Loire and Lower Normandy

Directed by

Oliver Dickinson

Produced by Jocelyne Barreau,

Université de Rennes 2

Assistant Director

Anthony Dickinson

Filmed and edited by

Oliver Dickinson

Sound

Claire Petit

Researcher

Marie Kerfant

Valse “Simple” and Valse “Ecossaise”

Traditional music

Performed by Joseph Rocher

Copyright LVP 2009

Discussion

De Botton suggests that the ‘problem’ of engagement is a modern phenomenon. In the past, we worked because we had to. Work was hard and hours were long. Questions of engagement in this context were almost irrelevant as the result of not working hard was severe physical deprivation.

‘Management’, such as it existed, simply saw its role as ensuring that levels of output were maintained. To use the common adage, management was all stick and no carrot.

Now, according to de Botton, there is something of an inversion. Management is now so preoccupied with ‘motivation’ and ‘engagement’ through the soft rhetoric of the HR department, that work has become almost more pleasurable than the rest of our life.

Moreover, we seek meaning and self-identity through our work. We have expectations that our goals should be realised through this work and are dissatisfied if they are not.

However, de Botton’s account of the gentle ironies of modern office life does ignore the large ‘hidden’ sector of the labour market in which work exerts a real physical cost and engagement is simply the result of economic necessity.

The final video offered a testament to the experiences of a handful of workers in France. However, we should also remember the harsh working environments faced by many workers in the developing world, many of whom are making the cheap products that sustain our modern economies and enable us to enjoy more pleasant work.

3 The contemporary emphasis on employee engagement

It is perhaps in recognition of changes in people’s work and the growing emphasis on the delivery of ‘services’ that the idea that senior strategic management should pay serious attention to employee engagement is growing.

It is sometimes suggested that this is just as important – if not even more important – during times of economic recession when there is risk of workers feeling alienated and insecure.

Employee engagement also represents big business for many consultancy firms that emphasise the importance of employee engagement and market their ‘solutions’. Virtually all the larger international firms have some presence and some product ‘offer’ in the area of employee engagement. For example, Gallup Consulting (2009) claims to maintain one of the most comprehensive global databases linking employee engagement to business outcomes. These include measures of retention, productivity, profitability, customer engagement and safety. The database is updated annually and the firm suggests that this enables clients to benchmark their organisation’s employee engagement levels against data collected in 45 languages from 5.4 million employees in 504 organisations in 137 countries.

Outside the normal commercial consultancies are organisations such as the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) and the Institute for Employment Studies (IES). Reilly and Brown (2009) of the IES report that employee engagement is far more than a new fad.

Another indicator of the perceived importance of employee engagement is the way various governments have mobilised initiatives around the idea. In the UK, the Department of Business established a national commission on the theme headed by the industrialist David MacLeod. The MacLeod Commission reported in July 2009. We would like you to consider their findings in the next activity.

We must, however, exercise caution in evaluating the claims of management consultants. They are in the business of selling solutions to problems. How can we be sure that their solution is sound? Indeed, how can we be sure that the problem exists in the first place? Bear these issues in mind as you undertake Activity 1.3.

Activity 1.3 Why engagement?

Activity 3

Introduction

Purpose: to look in more detail at the claims made for employee engagement and reasons why it is considered particularly important to contemporary businesses. We shall do this by examining the objectives and findings of the MacLeod Report.

Task A

Begin by exploring the MacLeod commission report.

You will find it useful to examine it in full; although it is a lengthy document it is presented in a digestible form and there are a number of useful case studies.

Task B

Independent commentary on the report and its findings are found in the online version of HR magazine. Read the article and click through the related links.

Task C

Reflect and make notes about the following questions:

- The report offers a number of enablers for improving employee engagement in the workplace. What are these?

- Consider their relevance to your workplace. How might they be applied?

- Do you think they offer a route for increasing levels of engagement in your organisation?

- More generally, do you think these principles are universally applicable?

Discussion

The MacLeod report identifies four enablers as being particularly relevant for engagement:

- Leadership is necessary to provide a narrative about organisational purpose and how employees can contribute to this purpose.

- Engaging managers should facilitate and empower rather than control or restrain.

- Voice represents the central role of employees in providing views that are listened to and acted upon.

- Integrity describes a situation where behaviour is consistent with values which lead to trust.

As with Activity 1.1, everyone’s organisational experiences will differ. The question is whether the presence (or otherwise) of these enablers is seen as leading to high levels of engagement. Were you able to provide illustrations for each of the enablers in practice?

Conclusion

Employee engagement is attracting a great deal of interest from employers across numerous sectors. In some respects it is a very old aspiration – the desire by employers to find ways to increase employee motivation and to win more commitment to the job and the organisation. In some ways it is ‘new’ in that the context within which engagement is being sought is different. One aspect of this difference is the greater penalty to be paid if workers are less engaged than the employees of competitors, given the state of international competition and the raising of the bar on efficiency standards. A second aspect is that the whole nature of the meaning of work and the ground rules for employment relations have shifted and there is an open space concerning the character of the relationship to work and to organisation which employers sense can be filled with more sophisticated approaches.

But there is reason to worry about the lack of rigor that has, to date, often characterised much work in employee engagement. If we continue to refer to ‘engagement’ without understanding the potential negative consequences, the core requirements of success, and the processes through which it must be implemented, and if we cannot agree even to a clear definition of what people are supposed to be engaged in doing differently at work (the engaged ‘in what’ question), then engagement may just be one more ‘HR thing’ that is only here for a short time. On a positive note, there is now a wider array of measurement techniques with which to assess trends in engagement and an associated array of approaches to effect some change. Thus, aspiration can more feasibly be translated into action.

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Cover image fdecomite in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Licence.

Text

De Botton, A. (2009) 'The new work order', Henley, J. The Guardian, 24 March. Copyright © Guardian News & Media Ltd 2009.

Images

1: iStockphoto.com.

AV

Activity 1.2: ‘My work, my sorrow’ interviews on physical distress at work in France today, © LVP Limited (2009), London.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.

Copyright © 2016 The Open University