Managing and managing people

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 19 April 2024, 5:04 AM

Managing and managing people

Introduction

You probably have a variety of reasons for wanting to learn about management. The main one is almost certainly that you want to improve your effectiveness as a manager. If so, it helps to have a clear idea of what managers do and what is meant by managerial ‘effectiveness’. To do this, you need to be able to identify your roles as a manager and those factors which influence your effectiveness – and these lie not only within yourself but also in your working environment. They include your job, your organisation, and the people you work with. Then you will need to diagnose what you might do to improve your own managerial performance, and take a first step to improve it.

This free course, Managing and managing people, is an adapted extract from the Open University course B628 Managing 1: organisations and people.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand what is meant by management and managerial effectiveness

identify the roles which are fulfilled while working as a manager

identify managerial activities that contribute to managerial effectiveness

identify a cause of stress in managerial life from a range covering mismatches between capabilites and role, player-manager tension and everyday stressors

understand time pressures and the need for time management.

1 What do managers actually do?

In this course we provide a number of views on the nature of management and what managers actually do. Then we look at the kinds of problems and issues that you deal with in your management role: we hope you will see that they have a common thread, whatever your particular sector of work. We offer you a variety of ways of looking at your job to help you to view your work more systematically and analytically. We consider some of the factors that can influence your effectiveness as a manager. Finally, we look at some of the problems that can arise when you move into management and how you might deal with them.

No two organisations are the same. No two management jobs are identical. No two situations are ever precisely the same. This explains why there is no one ‘best way’ of managing. What is appropriate in one organisation, at one time, in one situation and for one manager may not be appropriate in another. Understanding how your organisation, situation and practices are different from others provides you with valuable insights and learning that few textbooks can provide.

What do we mean by management? Most writers on management in this part of the twenty-first century would agree that it is the planning, organising, leading and controlling of human and other resources to achieve organisational goals efficiently and effectively. If you can relate your activities to this description then you are a manager – even if the word manager is not part of your job title. You may have only one or two people for whom you are responsible, but if you work through them to achieve organisational goals, you are managing them together with the other resources you use. To manage requires certain aptitudes and skills. Often, however, the task of managing – especially if you are new to the role – may leave you with little opportunity to consider or analyse what you are doing. You may feel that you are responding to a range of demands without being in as much control of your work as you would like. Many new managers feel like this. At some stage, most managers feel ill-prepared for their role and wonder whether they are doing the ‘right’ things. Consider the following example.

Box 1 The world of management

Carly had to admit that being promoted to Section Manager wasn’t quite what she thought it would be. For her first review meeting with her line manager she had been asked to prepare an outline of her views on the job. Over the last three days, Carly had been making quick notes in her diary. As she read her list to her line manager she found it depressing:

- Constant interruptions! I can never spend enough time on a task.

- I always seem to be reacting to events and requests rather than initiating them.

- Most of my time is spent on day-to-day matters.

- I always have to argue about work responsibilities and resources.

- I never have time to think – and decisions always need to be made immediately.

- I seem to spend all my time talking to people and never actually doing anything.

When Carly finished speaking, she apologised. Her line manager laughed and said: ‘Welcome to the world of management!’

This confusing world has been the subject of much analysis by management writers who have tried to make sense of the contradictions and time pressures that characterise most management jobs. One of the most well-known definitions of what management is and what managers do was given by Henri Fayol, a French mining engineer who, in 1916, published a book on management. In it he defined management as a process involving

- forecasting and planning

- organising

- commanding

- coordinating

- controlling.

The simple division of a manager’s job into these separate elements remains a powerful idea, although now we would refer to ‘commanding’ as leading.

2 What is managerial effectiveness?

There are no absolute measures of managerial effectiveness. Organisations have aims and objectives, and managers are effective when they help their organisation to achieve these aims and objectives. Thus, it is important that every manager (and employee) knows the purpose of their organisation, the purpose of their job and the work-specific objectives they must meet.

There are various ways of explaining the purpose of a job, and we consider two approaches here.

The most common term is key performance indicators, or KPIs. Setting KPIs is often an organisation-wide process. One version of this process is Management by Objectives. Variations of this are found in all types of organisations, although the process is often no longer referred to as Management by Objectives.

Management by Objectives aims to identify key areas in a person’s work and to set targets against which his or her performance (or effectiveness) may be measured.

Management by Objectives is a simple idea which often proves to be very difficult to apply. Peter Drucker, a well-known writer on management, suggests that effective managers follow the same eight practices. They:

- ask ‘what needs to be done’

- ask ‘what is right for the enterprise’

- develop action plans

- take responsibility for decisions

- take responsibility for communicating

- focus on opportunities

- run productive meetings

- think and say ‘we’ rather than ‘I’.

The first two practices give managers the knowledge they need. The next four help them convert this knowledge into effective action. The last two ensure that the whole team or organisation feels responsible and accountable. Most of the practices are applicable at all levels of management.

3 What does your effectiveness depend on?

At least four sets of factors influence your effectiveness as a manager, and not all of them are under your direct control.

- You. In the first place, there is you. You bring a unique blend of knowledge, skills, attitudes, values and experience to your job, and these will influence your effectiveness. If you have been a manager for some time, you will remember some of the mistakes you made as a new manager, and can see how your greater skills now help you to be more effective.

- Your job. Then there is the job that you do. It is likely to have many features in common with other managerial jobs, but just as you are unique, so is your job in its detailed features and some of its demands on you. There may be a good or bad match between your skills and the demands of the job, and this affects your potential effectiveness.

- The people you work with. The people you work with exert a major influence on how effective you can be as a manager. Descriptions of a manager include ‘a person who gets work done through other people’, ‘someone with so much work to do that he must get other people to do it’, and ‘the person who decides what needs doing, and gets someone else to do it’. Perhaps surprisingly they get close to the truth with their emphasis on the importance of people for the achievement of a manager’s work. One measure of managerial effectiveness is the extent to which a manager can motivate people and coordinate their efforts to achieve optimum performance. However, in most settings managers do not control people in the way that they can control the other resources that they need to get their work done. Rather, managers are dependent on people. Managers’ effectiveness is limited by the qualities, abilities and willingness of these people.

- If we had been writing 50 years ago, we would have mentioned that there are organisations where commands are frequently given, for example, the military services, the fire service and the police service. In the twenty-first century there will still be situations where a manager in such organisations gives an order and expects immediate compliance. However, many of the processes in organisations such as these now involve softer methods of managing staff.

- Your organisation. Finally, the organisation you work in determines how effective you can be. How the organisation is structured and your position in it affect your authority and your responsibilities, and impose constraints on what you are able to achieve. Similarly, the culture of the organisation, with its unwritten norms and ways of working, also influences your ability to be effective as a manager.

Effectiveness, then, does not come from just learning a few management techniques. Some techniques are important and necessary, but managerial effectiveness is more complex. It is influenced by a range of factors – you, the job you do, the people you work with, and the organisation you work in.

4 Your job

Did you find your management job hard to describe? This section should provide you with some of the reasons why this might be. Many managers find it is something of a relief to discover that they are not alone in struggling to make sense of what we call management. As you read this section consider the following questions:

- Do you feel that you are responding to demands instead of being in control?

- Do you follow any of Drucker’s eight practices of effective managers?

- How much do you think your effectiveness depends on you, your role, the people you work with and your organisation?

- How important is each of these four elements in the effectiveness equation?

When you read with questions in mind about you and your own organisation, it helps you to process the meaning of what you are reading. Reading becomes active rather than passive, and helps you to remember what you have read.

This section explores in a different way what managers do. It considers managerial tasks and roles. As you read, consider the main day-to-day tasks in which you are engaged. Then take note of how Mintzberg categorises managerial activities into roles. Which roles are dominant in your job, or do you perform them equally? Are there any roles that you don’t perform? Make notes as you read, as these will help you with Activity 2.

4.1 The nature of the job

The pressures of managerial life and the generally fast pace of managerial work mean that few managers have any real opportunity to reflect on the nature of their job. Even if they do, it is not easy to make sense of the work that a lot of managers do. Research in the USA found that the manager’s day included a series of short, unconnected activities. At first sight, a lot of the things that managers spend their time doing don’t seem clearly connected to the achievement of their goals.

In an article in the Harvard Business Review, ‘What effective general managers really do’, John P. Kotter examined the seemingly inefficient ways in which many managers appear to work. He kept records of what they did and he found that their activities are brief, fragmented and frequently unplanned. They spend 70% or more of their time in the company of other people, sometimes with outsiders who seem to be unimportant. They hold lots of very brief conversations on seemingly inconsequential matters, often unconnected with work, and they do a lot of joking. They ask many questions but rarely seem to make any ‘big’ decisions during their conversations. They seldom tell people what to do. Instead, they ask, request, persuade and sometimes even intimidate. Do these descriptions fit anyone you know (perhaps you, or your boss, or the head of your organisation)?

Kotter says this behaviour is ‘less systematic, more informal, less reflective, more reactive, less well-organised, and more frivolous’ than a student of management would ever expect. However, he says the behaviour can be explained. He suggests that the two main dilemmas in most senior managers’ jobs are:

- working out what to do despite uncertainty, great diversity, and an enormous amount of potentially relevant information

- getting things done through a large and diverse set of people despite having little direct control over most of them.

Thus, the seemingly pointless and inefficient behaviour is, in fact, an efficient and effective way of:

- gathering up-to-the-minute information on which to base decisions

- building networks of human relationships (networks that are often very different from the formal organisation structure) to enable them to get their decisions implemented.

Kotter’s explanation is just one way of making sense of the seeming chaos of what managers do. Various other ways have been suggested. We will next consider two which we see as very useful.

4.2 The ‘job description’ approach

One way of gaining a clearer picture of what you do as a manager would be to list all your activities in a giant job description. An example is set out below. The list does not describe the job of an actual manager but sets out typical managerial activities.

| The manager’s job | |

| Makes forecasts | Monitors progress |

| Makes analyses | Exercises control |

| Thinks creatively/logically | Determines information needs |

| Calculates and weighs risks | Establishes/uses management information systems |

| Makes sound decisions | Manages his or her time |

| Determines goals | Copes with stress |

| Sets priorities | Adjusts to change |

| Prepares plans | Develops his or her skills and knowledge |

| Schedules activities | |

| Establishes control systems | |

| Sets/agrees budgets | |

| The manager and his or her team | |

| Builds and maintains his or her team | Makes presentations |

| Selects staff | Conducts meetings |

| Sets performance standards | Writes reports and correspondence |

| Raises productivity | Interviews |

| Motivates people | Counsels and advises |

| Arranges incentives | Identifies organisational problems |

| Designs jobs | Creates conditions for change |

| Improves the quality of working life | Implements/manages/copes with change |

| Monitors and appraises performance | Designs new organisation/team structures |

| Harmonises conflicting objectives | Establishes reporting lines |

| Handles conflict | Develops internal communication systems |

| Leads | Takes account of environmental factors affecting the organisation (economic, environmental, technological, social, political) |

| Adopts appropriate management styles | |

| Communicates effectively | |

| Negotiates/persuades/influences |

Listing and grouping a manager’s activities goes a little way towards making some sense out of the complexities of managerial work, but it does not offer any explanations. Another difficulty is that many other jobs have many of these components. Nurses, sales staff, engineers, chefs and cooks, and office workers, for example, often carry out some of these activities.

4.3 The roles of a manager

One of the best-known attempts to make some sense out of the seeming chaos of what managers actually do was made by Henry Mintzberg in 1971. He studied a number of chief executives and kept records of all their activities, all their correspondence and all their contacts during the period of the study. His analysis of the data concluded that managerial work had the following six characteristics.

- The manager performs a great quantity of work at an unrelenting pace.

- Managerial activity is characterised by variety, fragmentation and brevity.

- Managers prefer issues that are current, specific and ad hoc.

- The manager sits between his organisation and a network of contacts.

- The manager shows a strong preference for verbal communication.

- Despite his heavy obligations, the manager appears to be able to control his own affairs.

Note that the study related to chief executives. Mintzberg’s main question was ‘Why did the managers do what they did?’ His answer was that they were fulfilling certain roles. He identified 10 different roles into which he was able to fit all the activities he observed. He grouped the 10 roles under three broader headings on the grounds that, whatever they were doing, they were invariably doing one of three things: making decisions, processing information, or engaging in interpersonal contact.

4.3.1 Interpersonal roles

These cover the relationships that a manager has to have with others. The three roles within this category are figurehead, leader and liaison. Managers must act as figureheads because of their formal authority and symbolic position representing the organisation. As leaders, managers have to consider the needs of an organisation and those of the individuals they manage and work with. The third interpersonal role, that of liaison, deals with the ‘horizontal’ relationships which studies of work activity have been shown to be important for a manager. A manager usually maintains a network of relationships, both inside and outside the organisation. Dealing with people, formally and informally, up and down the hierarchy and sideways within it, is thus a major element of the manager’s role. A manager is often most visible when performing these interpersonal roles.

4.3.2 Informational roles

Managers must collect, disseminate and transmit information and these activities have three corresponding informational roles: monitor, disseminator and spokesperson.

In monitoring what goes on in the organisation, a manager will seek and receive information about both internal and external events and transmit it to others. This process of transmission is the dissemination role, passing on information. A manager has to give information concerning the organisation to staff and to outsiders, taking on the role of spokesperson to both the general public and those in positions of authority. Managers need not collect or disseminate every item themselves, but must retain authority and integrity by ensuring the information they handle is correct.

4.3.3 Decisional roles

Mintzberg argues that making decisions is the most crucial part of any managerial activity. He identifies four roles which are based on different types of decisions; namely, entrepreneur, disturbance handler, resource allocator and negotiator.

As entrepreneurs, managers make decisions about changing what is happening in an organisation. They may have to initiate change and take an active part in deciding exactly what is done – they are proactive. This is very different from their role as disturbance handlers, which requires them to make decisions arising from events that are beyond their control and which are unpredictable. The ability to react to events as well as to plan activities is an important aspect of management. The resource allocation role of a manager is central to much organisational analysis. A manager has to make decisions about the allocation of money, equipment, people, time and other resources. In so doing a manager is actually scheduling time, programming work and authorising actions. The negotiation role is important as a manager has to negotiate with others and in the process be able to make decisions about the commitment of organisational resources.

Mintzberg found that managers don’t perform equally – or with equal frequency – all the roles he described. There may be a dominant role that will vary from job to job, and from time to time.

It is important to note that many non-managers in organisations seem to have these sorts of interpersonal, informational and decisional roles. For example, a hotel receptionist is fulfilling an interpersonal role when she meets the hotel guests’ needs by communicating with the room attendants and restaurant staff. A car park attendant who monitors how full the car park is and, when necessary, displays the sign ‘car park full’ is disseminating information. When the same attendant sends the larger cars to the areas of the car park where there is more space, he is acting as a resource allocator. But in each case routine situations are being handled in routine ways. In contrast, the situations managers deal with differ in the degree of routine, the size and scope and complexity of the activities in which they are involved, and the responsibilities associated with these activities.

Activity 1 The Mintzberg roles

In this activity you will identify the Mintzberg roles you have performed in the last week.

First, consider Mintzberg’s 10 roles (figurehead, leader, liaison, monitor, disseminator, spokesperson, entrepreneur, disturbance handler, resource allocator, negotiator). Look back over the previous few pages if you need reminding of the three categories, or any details. Then, think about the main managerial tasks you carried out last week.

Identify THREE different tasks that occupied you most and match them to three of Mintzberg’s 10 roles. Record the activities below in the appropriate dialogue boxes. The boxes will help you to structure your response to the activity. Next, think about any of Mintzberg’s roles that you don’t perform.

Finally, note what changes you would like to make in your roles to increase your contribution to the success of your organisation, or your part of the organisation. When considering changes it is always good practice to identify who might be affected by the changes, a timescale and whether consultation with other people is needed. Record your responses below.

The purpose of this activity is to help you to be more aware of the management roles you perform in your job and to consider changes or improvements.

The Mintzberg roles

Task 1:

Task 2:

Task 3:

Mintzberg roles I don’t carry out:

Changes I could make:

The timescale of the potential changes:

Who I should consult:

Comment

Comment

It would be unusual if you carried out every one of Mintzberg’s 10 roles, either in one week of work or in your management job overall. But it would also be unusual if you did not undertake several of the roles. The type and range depend on the context in which you work. It would also be unusual for all your managerial activities to have equal importance in your job. The learning point to be gained is that while many people are engaged in something called management, they are not engaged in exactly the same thing, as you will see when you compare your results with those of other students. The important difference is context. This determines your management roles in any given situation, including what type of organisation you work for.

The following section takes you more deeply into the context of management – the particular situation that you work in. The text sets out different types of demands on you – things you must do; different types of constraints – factors that limit what you can do; and choices that you may have. As you read, consider your job in terms of each type of demand, constraint and choice. This will prepare you for Activity 2.

5 The demands, constraints and choices of your job

How much freedom do you have to do your job as a manager? What factors place limits on your effectiveness? More importantly, what can you do about such limitations? Rosemary Stewart developed a concept which enables jobs to be examined in three very important ways: the demands of the job, which are what the job-holder must do; the constraints, which limit what the job-holder can do; and the choices, which indicate how much freedom the job-holder has to do the work in the way she or he chooses. Her purpose was to show how dealing appropriately with demands and constraints, and exercising choices, can improve managers’ effectiveness. Consider the following two examples.

Job A

Simon manages a team of health and safety training officers in a large chemicals company. Although he has a general responsibility for ensuring that staff receive appropriate training, he has little influence on the content of training sessions as a result of health and safety legislation laid down by country laws and when training takes place, but he can influence how the training is provided and other aspects of it.

Job B

Arshia manages a drop-in advice centre for homeless teenagers. She has relative freedom in deciding what, when and how assistance is offered within the range of organisational capability. The management committee has just set out a new strategic direction for the organisation which Arshia believes can be improved on, and which she can influence.

Note the differences between the demands and constraints imposed in each case, and how these demands and constraints will place limitations on the respective choices that Simon and Arshia can make.

Demands of the job

Demands are what anyone in the job must do. They can be ‘performance demands’ requiring the achievement of a certain minimum standard of performance, or they can be ‘behavioural demands’ requiring that you undertake some activity such as attending certain meetings or preparing a budget. Stewart lists the sources of such demands as being:

- Manager-imposed demands – work that your own line manager expects and that you cannot disregard without penalty.

- Peer-imposed demands – requests for services, information or help from others at similar levels in the organisation. Failure to respond personally would produce penalties.

- Externally-imposed demands – requests for information or action from people outside the organisation that cannot be delegated and where there would be penalties for non-response.

- System-imposed demands – reports and budgets that cannot be ignored nor wholly delegated, meetings that must be attended, social functions that cannot be avoided.

- Staff-imposed demands – minimum time that must be spent with your direct reports (for example, guiding or appraising) to avoid penalties.

- Self-imposed demands – these are the expectations that you choose to create in others about what you will do; from the work that you feel you must do because of your personal standards or habits.

Constraints

Constraints are the factors, within the organisation and outside it, that limit what the job-holder can do. Examples include:

- Resource limitations – the amounts and kinds of resources available.

- Legal regulations.

- Trade union agreements.

- Technological limitations – limitations imposed by the processes and equipment with which the manager has to work.

- Physical location of the manager and his or her unit.

- Organisational policies and procedures.

- People’s attitudes and expectations – their willingness to accept, or tolerate, what the manager wants to do.

To this list for today’s world we would add factors which will impose constraints such as:

- ethics – your own and those to which your organisation adheres

- the environment – climate change and remediation.

Choices

Many managerial jobs offer opportunities for choices both in what is done and how it is done, though the amount and nature of choice vary. Managers can also exercise choice by emphasising some aspects of the job and neglecting others. Often they will do so partly unconsciously. The main choices are usually in:

- what work is done

- how the work is done

- when the work is done.

Analysis of your job using these concepts of demands, constraints and choices can be revealing, particularly if it leads to the recognition that one or other aspect needs changing.

Note that demands and constraints also apply to many employees who work in the organisation. Choices, however, often do not apply to employees doing routine jobs.

Activity 2 Demands and constraints

Consider the demands made on you when you carry out your job. Rate each type of demand from 1 (low) to 10 (high), and provide an example in cases where a demand is high. Then consider the factors that place constraints on what you can do. Rate these in the same way and record them. Provide an example in cases where a constraint is high.

Demands

Manager-imposed:

Peer-imposed:

Externally-imposed:

System-imposed:

Staff-imposed:

Self-imposed:

Constraints

Resource limitations:

Legal regulations:

Union agreements:

Technological limitations:

Physical location:

Policies and procedures:

Attitudes and expectations:

Ethical considerations:

Environmental concerns:

Comment

Activity 2 should provide you with a picture of the demands and constraints you are subject to. The choices you have in your job will be greater when you have few demands and few constraints, although not many managers find themselves in that position. Most managers face substantial demands, but often from only two or three sources. Similarly, most managers have a number of constraints but not in all the areas shown. Activity 4 demonstrates how your context shapes what, how and when your work, and that of your work group, is done. It also has an important purpose in this course too. When you are resolving workplace issues you will always need to consider demands, constraints and choices. You will also need to consider the extent to which you have an influence over some demands and constraints. As you carried out Activity 2, you may have begun thinking about this!

The last four sections of this course all deal with pressure on managers and the stress that can result. They covers the following topics around managing pressure, stress and time:

Your management skills: This section sets out some recognised skills that managers need in order to be effective. Note that if your capabilities don’t match what your job requires, then the result is likely to be frustration and stress. However, the reason you are studying this course is likely to be to improve your skills and capabilities. In this case, you are taking active steps to remedy this situation.

Transition into management: This section deals with a particular situation – that of the new manager moving from ‘operating’ to managing. Any transition has the potential to cause stress. However, the understanding that the transition is a process and that there are actions a person can take to become an effective manager is likely to be stress-reducing. You may have already experienced this particular transition. If you are experiencing it now, however, or made the transition some time ago but not entirely successfully, consider what kinds of adjustments you could make.

Recognising pressure and avoiding stress: This section considers common causes of stress with the emphasis on management and managers. This reading will be useful however long you have been a manager. What particular pressures are you under this week? What methods of reducing stress are open to you?

Managing your time: This section takes you through the main points of time management. As you read, make a note of the ways in which your time is used and what you might do to save time.

6 Your management skills

Imagine always having to work at a level above your capabilities. Alternatively, imagine doing a job that frustrates you because it demands few of your skills. Both situations are likely to be stressful. Thus, matching your own capabilities to the requirements of your management job is important for a variety of reasons.

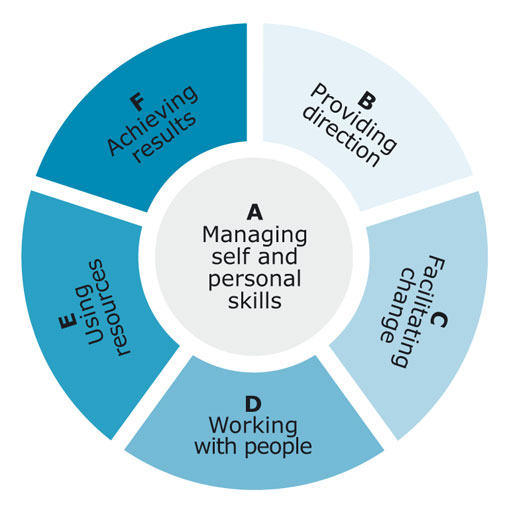

Which managerial skills and competencies are most frequently used in managerial work? Obviously, the answer to this question will vary enormously from job to job. However, there are recognised ‘sets’ of skills and competencies. One such set of occupational standards for management and leadership has been developed in the UK by the Management Standards Centre. The broad categories of skills and competencies which they cover are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Skills and competencies

The diagram shows six functional areas (A–F) with Managing self and personal skills having a central position, indicating their contribution to the other five areas of competence. Each area contains a number of ‘units’ of competence, numbering 47 in total. For example, listed under Working with people are 12 ‘units’ set out in Table 2.

| D1 | Develop productive working relationships with colleagues |

| D2 | Develop productive working relationships with colleagues and stakeholders |

| D3 | Recruit, select and keep colleagues |

| D4 | Plan the workforce |

| D5 | Allocate and check work in your team |

| D6 | Allocate and monitor the progress and quality of work in your area of responsibility |

| D7 | Provide learning opportunities for colleagues |

| D8 | Help team members address problems affecting their performance |

| D9 | Build and manage teams |

| D10 | Reduce and manage conflict in your team |

| D11 | Lead meetings |

| D12 | Participate in meetings |

These 12 competencies recognise the importance of the soft skills which managers bring to their role. Overall, the standards are designed to act as a benchmark of best practice.

A simpler scheme of management skills was suggested by Robert L. Katz (1986) in the Harvard Business Review. Katz, who was interested in the selection and training of managers, suggested that effective administration rested on three groups of basic skills, each of which could be developed.

Technical skills. These are specialist skills and knowledge related to the individual’s profession or specialisation. Examples include project management skills for engineers building bridges, aircraft and ships. Katz pointed out that training programmes tend to focus on skills in this area. These skills are easier to learn than those in the other two groups.

Human skills. Katz defines these as the ability to work effectively as a group member and to build cooperative effort in the team a person leads.

Conceptual skills. Katz saw these as being the ability to see the significant elements in any situation. Seeing the elements involves being able to:

- see the enterprise as a whole

- see the relationships between the various parts

- understand their dependence on one another

- recognise that changes in one part affect all the others.

This ability also extends to recognising the relationship of the individual organisations to the political, social and economic forces of the nation as a whole. This has since been called the ‘helicopter mind’, that is, being able to rise above a problem and see it in context. These conceptual skills are likely to be demonstrated by a manager or executive higher in the organisation. Indeed, at these higher levels of management, organisations require these skills.

One area of skill that Katz did not list, but which is becoming increasingly recognised (though often grudgingly) as a basic requirement for managerial effectiveness is a political skill in handling organisational politics. These politics cover pursuit of individual interests and self-interest, struggles for resources, personal conflicts, and the ways in which people and groups try to gain benefit or achieve goals.

6.1 Characteristics of an effective manager

Which special characteristics, if any, do effective managers possess? What makes a manager effective in one organisation, one situation, at one time, can be ineffective in another organisation, situation or time. There are few universals in management. But some researchers do claim to have identified a range of characteristics that are common to the more successful managers. Eugene Jennings (1952) studied 2,700 supervisors selected as most effective by senior managers in their organisations and by the people who worked under them. These supervisors also met effectiveness criteria in terms of department productivity, absentee rate and employee turnover. The identified traits and behaviours are set out in Box 2 in order of priority.

Box 2 Traits and behaviours

Gives clear work instructions: communicates well in general, keeps others informed.

Praises others when they deserve it: understands importance of recognition; looks for opportunities to build the esteem of others.

Willing to take time to listen: aware of value of listening both for building cooperative relationships and avoiding tension and grievances.

Cool and calm most of the time: maintains self-control, doesn’t lose her/his temper; can be counted on to behave maturely and appropriately.

Confident and self-assured.

Appropriate technical knowledge of the work being supervised: uses it to coach, teach and evaluate rather than getting involved in doing the work itself.

Understands the group’s problems: as demonstrated by attentive listening and trying to understand the group’s situation.

Gains the group’s respect, through personal honesty: doesn’t try to appear more knowledgeable than is true; not afraid to say, ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I made a mistake’.

Fair to everyone: in work assignments, consistent enforcement of policies and procedures; avoids favouritism.

Demands good work from everyone: maintains consistent standards of performance; doesn’t expect group to do the work of a low-performing worker; enforces work discipline.

Gains people’s trust: willing to represent the group to higher management, regardless of agreement or disagreement with them.

Takes a leadership role: works for the best and fair interests of the work group; loyalty to both higher management and the work group.

Humble, ‘not stuck up’: remembers that s/he is simply a person with a different job to do from the workers s/he supervises.

Easy to talk to: demonstrates a desire to understand without shutting off feedback through scolding, judging or moralising.

You are the best person to assess whether your capabilities match the requirements of your management job, as each managerial role will differ according to a variety of factors. It is not easy to make such an assessment, but it may help you if you consider the way in which you are line managed. However, managers tend to use their own line manager as a role model regardless of whether what is being modelled is appropriate and effective. Thus, it is wise to consider how, ideally, you would like to be managed and to take note of the way in which other managers manage their staff. Then you will be in a better position to assess your own capabilities. The advantage will be that you will have examples to follow – and ones to avoid!

7 Transition into management

Ironically, the same skills that helped individuals to become managers may prevent them from becoming an effective manager. One of the most common reasons for promoting someone to managerial status is that he or she has excelled as a ‘player’. Most sales managers have been very successful salespeople, most production managers have worked well on the shop-floor, most office managers have been very good secretaries or administrators. Presumably, the rationale is that if you can do it well, you can manage it equally well. While the majority of managers find the transition to a managerial position stimulating (if stressful at times), some find it more difficult. The reason is usually that they find it difficult to stop doing their previous job. They continue to ‘play’ rather than manage. They try to retain some of the roles they did well as operators, and this can reduce their effectiveness as managers.

This problem is known as the player–manager syndrome. Understanding the syndrome may help you to change your roles, or help other managers to be more effective. In some jobs, there is a complete break when a person moves from operating to managing. For instance, not many airline managers continue to fly aeroplanes. However, in many management jobs a certain amount of operating is still needed. There may be expectations in your organisation that you should continue in some of your former operating roles. When changing to a management job it is important to consider whether time spent operating improves or damages your management role. You may want to use the opportunity to change the emphasis of your work so that it is more about your management role and fits into your available time more easily.

Some of the reasons people give for finding it hard to stop doing their old role and adjust to the new one are set out below. Solutions are also suggested on the kinds of adjustments you can make.

- It is important to keep my specialist skills up-to-date. You can maintain your skills by guiding, teaching or coaching in order to perfect someone else’s technique. This helps your team members to develop new competences.

- I believe it helps my leadership image if I show that I can perform as well as any of my staff and can do anything I ask them to do. Your leadership and ability to perform to a high standard will be better demonstrated by sharing management issues with your staff. Share with them how the objectives could be set, how to plan and organise them, how to set up a control mechanism and how to evaluate the achievement. This develops valuable project management skills in your team.

- My staff expect me to remain ‘one of them’. If you share with your staff aspects of your managerial thinking – its planning, organisation and coordination – you’ll demonstrate the particular contribution you are making to the team effort.

- I feel more secure and comfortable doing something I know I can do well. By doing tasks which are within the capabilities of your staff, you could be denying them the opportunity to gain the experience.

- I believe it is often quicker and easier to do the job myself than leave it to somebody who cannot do it so well. Helping others to learn yields benefits in the long run. Take every opportunity to develop your staff, and do this in a planned fashion.

- I need to carry out work myself because I don’t have enough people to do the job. When there are unexpected staff shortages or sudden demand, for example, you may need to respond by doing the job yourself. But who will be managing while you are performing? If a staff shortage is long-standing you will need to try to get extra resources or to reduce the levels of activity. When times are difficult your team needs you to plan work activities, to be an effective figurehead and spokesperson for your department and to influence decisions taken elsewhere.

- My manager gets very involved and expects me to do so as well. This is a difficult situation to deal with because it may involve trying to influence the attitude of the person who manages you. However, it is important to demonstrate your effectiveness as a manager if you are able to. This includes giving evidence of the value of your contributions to planning and budgeting; the effectiveness of your control systems; and your interest in, and influence on, job design, the motivation of your staff and morale in your department. By doing the job yourself you will not demonstrate your qualities as a manager unless you are able to manage the work of your team in addition to your own work.

- My job is largely functional and involves a good deal of operating as well as managing. If you are a manager who maintains a professional role or particular specialism, you must spend some time on it. But the functions of manager and professional or specialist functional leader overlap a good deal, as is suggested in Figure 1.

Figure 2 The overlap between managerial and professional or specialist functions

Many people like to spend their time and energy operating rather than managing. Operating is often easier and more rewarding than managing, and it is usually less demanding and carries fewer risks. However, you need to maintain the right balance. To do this you need to be able to separate operating and managing very clearly. New managers can find the transition difficult. Older managers may have failed to make the transition.

7.1 Making the transition

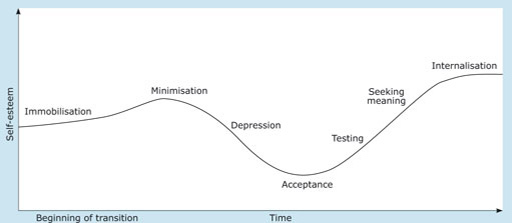

Seven stages of transition have been identified which apply to management and indeed many other life and work transitions, especially when a transition has been quite sudden (Adams et al., 1976). These are set out below.

- Immobilisation: the initial ‘frozen’ feeling when you do not know what to make of your new role.

- Minimisation: you carry on as though nothing has changed, perhaps denying inside that you really have new roles as a manager.

- Depression: when the nature and volume of the expectations upon you have sunk in and you feel you cannot cope; depression can be accompanied by feelings of panic, anger and blame.

- Acceptance: when you begin to realise there are things you are achieving and more you could achieve, and that you have moved on from what you used to do.

- Testing: when you begin to form your own views on what management is all about and even experimenting with what you can do.

- Seeking meaning: you find the inclination and energy to reflect upon and learn from your own and others’ behaviour.

- Internalising: you define yourself as a manager, not just in title but in what you think you are doing; you and your job have come to terms with each other.

The seven transition phases represent a sequence in the level of self-esteem as you experience a disruption, gradually acknowledge its reality, test yourself, understand yourself, and incorporate changes in your behaviour. Changes in level of self-esteem appear to follow a predictable path. Identifying the seven phases along such a self-esteem curve can help you to understand the transition process better. This is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3 The transition process

Although this seven-stage model describes transition as a sequence, not everyone in job transition will experience every phase. Each person’s progress is unique: one may never get beyond denial or minimisation; another may drop out during depression; and others will move smoothly and rapidly to the later phases.

8 Recognising pressure and avoiding stress

Most people would agree that a certain amount of pressure is tolerable, even enjoyable. Different people, of course, react in different ways to pressure. Some people tolerate more than others do. But we are often at our best when the adrenalin is flowing and when we are working under pressure to achieve good results within a limited time. Problems start when the pressure becomes too great or continues for long periods. It then becomes stress. It ceases to be enjoyable. In the UK, employees are absent for an average of eight days a year and stress is the fourth major cause of this absence (CIPD, 2008). The five main causes of work-related stress that CIPD identified were:

- workload

- management style

- relationships at work

- organisational change and restructuring

- lack of employee support from line managers.

These causes should alert you to the idea that, as a manager, you are just as likely to suffer from stress as to be the cause of it! How a manager can reduce stress among direct reports is covered elsewhere in this textbook.

It is important that managers are able to distinguish between pressure and stress so that they can avoid stress while making the best use of appropriate pressure. A simple way of differentiating between pressure and stress is by the effects that they have.

Most high achievers (and a lot of managers would fall into this category) find pressure to be positively motivating. They are able to respond to it energetically. Stress, on the other hand, is debilitating. It deprives people of their strength, their vitality and their judgement. The area of concern is where pressure becomes stress. Here, one needs to be constantly looking for tell-tale signs.

8.1 Causes of stress

The most common causes of stress are:

Demand. For the manager, demand will include responsibilities such as:

- responsibility for the work of others and having to reconcile overlapping or conflicting objectives – between group and organisation, between individuals and group, and between one’s own objectives and those of other managers

- responsibility for innovative activities, especially in organisations where there is a cultural resistance to change.

When these demands are excessive, they can be regarded as role overload which occurs when a manager is expected to hold too many roles. In the recent past, many organisations in Europe and the USA have responded to demands for cost reduction by ‘delayering’. This involves reducing the number of managers, while the amount of work to be managed remains the same. Some organisations have implemented delayering by requiring that the remaining managers do all the work of managers now removed. They are also told to achieve the same quality as before. The managers affected may see this as an impossible task. Equally, role underload can be stressful if a person feels underused. Work overload and underload is different from role overload and underload. In work overload and underload, stress is created as a result of the quality and quantity of work demanded – either too much or too little.

Control. A manager’s role as coordinator can be stressful, especially where authority is unclear or resources are inadequate.

Role ambiguity, incompatibility and role conflicts.

- Ambiguity about management roles is often inevitable: they invariably combine a number of overlapping roles. Indeed, it is precisely this overlap that makes management jobs interesting and offers scope for creativity.

- Role incompatibility occurs when a manager’s expectations of role are significantly different from those of his or her staff and colleagues. Pressure to do things that do not feel appropriate or ‘right’ is stressful.

- Role conflict may occur when someone has to carry out several different roles. Although the manager may be comfortable about performing each role individually, there may be conflict when several roles are held at one time. This may include conflict between roles associated with home and family and roles associated with work.

Other major sources of stress that are not confined to managers but affect them include:

Relationship problems. People who have difficulties with their manager, their staff or their colleagues may exhibit symptoms of stress.

Support. All staff need adequate support from colleagues and superiors.

Career uncertainty. Uncertainty often occurs as a result of rapid changes in the economic situation inside and outside the organisation, in technology, in markets and in organisational structures.

8.2 Symptoms of stress

It is common for managers to seek work or responsibilities even though they know this will increase the pressure on them. The stimulus of responsibility, of achieving work or personal targets, and of working against deadlines provides much of the interest and satisfaction in their work. However, this pressure can become counter-productive if it is excessive – if you no longer feel in control and if the satisfaction of achievement fails to compensate for the stress of delivering the outcomes. At this stage you need to be able to identify the cause of the excess pressure and take measures to correct it. Your objective must be to maintain a level of pressure that you find stimulating and not threatening.

Symptoms of stress include being too busy or working longer hours, insecurity, an unwillingness to delegate, loss of motivation and indecision. Work performance may decline or become inconsistent. Other symptoms may include irritability and short temper, panic reactions, heavy reliance on tobacco, alcohol or drugs such as tranquillisers. All can be signs of other problems, but their presence should make you suspect stress.

Once you are aware of the causes of unproductive pressure, you are in a position to address the problem.

8.3 Reducing stress

Methods of reducing stress that work for the manager are also likely to be effective for the work team: less stress among direct reports will reduce demands on the manager. Possible actions include:

- Promoting collaborative working approaches. If you are careful to involve members of your team in making decisions about matters that affect them, they will be more likely to cooperate with you and with each other.

- Creating ‘stability zones’. These are areas of work over which you and members of your work group have some control, or a measure of control.

- Being alert to the actual demands being made on you and those in your work group.

- Ensuring that everyone knows their roles and the functions they are expected to fulfil.

- Setting yourself and others clear priorities and keeping an overview of everyone’s workload.

These actions will help you to monitor roles and workloads, to clarify expectations and help to provide staff with a sense of control and certainty, and to promote good relationships.

A final point is that it is common for managers to set themselves high standards in terms of both the quantity and the quality of their work. This is reinforced when the organisational culture creates an expectation of long working hours. If it is usual to hold breakfast meetings, this may create unreasonable pressures on staff who have school-age children. If these examples are familiar you should consider changing your own working practices and persuading other managers to change theirs.

We have considered mainly causes of stress which take place at work. There are many causes of stress in workers’ lives outside work. Some organisations make arrangements to help workers with their problems caused by issues outside work. Since this help can involve specialist knowledge, organisations may employ their own specialists for this. Managers need to know what the organisation’s policies are on stress with causes outside work, and what they should and should not do.

9 Managing your time

For many managers the most difficult and stressful problem they have to deal with is shortage of time: the work simply will not fit into the time available. Many courses and books are available on time management to train people in techniques for managing their time. As with so many management techniques, there is no magic solution, merely a good deal of common sense that you could work out for yourself – if you had time.

There are three principles in improving time management:

- work shedding

- time saving

- time planning.

9.1 Work shedding

By work shedding we mean:

- stopping doing some tasks

- changing the task method to one taking less time

- reducing the quality of some work

- transferring tasks to other people.

Getting rid of some of your work is an obvious solution. The problem for some managers is that they don’t know how to, or are unwilling to. They are perfectionists, worriers, interferers, individuals who cannot let go. The techniques of shedding work are simple. You need to:

- concentrate effort on your key activities

- delegate.

To concentrate on key activities requires you to identify carefully those tasks which must be done thoroughly. This does not mean that the others can be done to an unacceptable standard, but that you are better placed to allocate time and effort appropriately. The Pareto Principle, or the 80/20 law, should help you to sort out your priorities. It asserts, on quite strong evidence, that 80% of our results are generally produced by 20% of our effort – and that the remaining 80% of our effort is swallowed up in achieving that last 20% of our results. If this holds true for managers, then a lot of effort is devoted to jobs that don’t merit the effort. These jobs are candidates for shedding, or at least for receiving less attention. The trick, of course, is to identify the key 20% that means so much to your success.

Delegation is the other main device for shedding work. Delegation means giving someone the authority (and the necessary resources, including time) to do something on your behalf. We mainly use the term when transferring work to the people who work for us. When you do this you retain the responsibility for it. Responsibility has been compared with influenza – you can pass it on but you cannot get rid of it. In exercising your responsibility you must strike an appropriate balance between trust and interference. When we transfer work to another department, or to a supplier or customer, we would usually call this transferring, rather than delegating work.

9.2 Time saving and time planning

One approach to saving time is to identify the main wasters of time in your working life – and eliminate them. Some major time-wasters are:

- giving a higher priority to new email than is necessary

- accepting all telephone interruptions

- encouraging people to discuss their problems with you

- encouraging visitors

- holding meetings which are unnecessary, badly planned or badly conducted, or all of these

- reading slowly (much time spent reading documents)

- writing slowly (much time spent drafting)

- delaying starting important and urgent work, or procrastination (indecision)

- unnecessary or inefficient travelling.

To identify time-wasters such as these, try keeping a log of your time – even if only for a few days. This can help you to identify where time is being wasted. At 15-minute intervals throughout a working week, note the main tasks on which you have been working. You can save time in keeping your log by preparing a pro forma sheet with columns headed with your most likely activities. Then you can insert ticks and an occasional comment. At the end of the recording period you should analyse the entries in the columns. This will reveal the proportions of time that you are spending on each aspect of your work, and it should highlight time-wasters and jobs that could be shed.

To manage effectively you need some time every day when you can give your undivided attention to your key tasks. Interruptions to this time will damage your concentration and your ability to think clearly. You could identify an hour each day when you are simply not ‘available’. If you want to keep face-to-face conversations short, don’t sit down. When you want to end a face-to-face discussion when you are sitting, sum up and stand up. Make appointments with visitors to talk to them at a more appropriate time. Better still, if the visitor is located nearby, visit them; that way you retain control over the length of your visit. Colleagues will soon start to respect your time and privacy. It becomes a status symbol – and like all status symbols it should be visible but not ostentatious.

Meetings are one of the most notorious wasters of time. If they are your meetings, first decide if they are necessary. If they are, then plan them carefully. Set an agenda, set a time limit, and keep discussion strictly to the point.

If you are a slow reader, you can learn how to skim read. If you draft slowly, try a different method. For example, voice-recognition software can speed up your ‘writing’ because it enables you to speak your ideas rather than putting them down on paper. Time spent socialising and on visits may be important to build networks and good relationships. If it is one of your key activities, do it. If not, limit it. Procrastination is possibly the worst ‘thief’ of time for many managers. Difficult or disliked decisions and tasks are delayed in the hope, rather than the expectation, that they will resolve themselves or that new information will come to hand which will make things clearer. First, identify if there really is a difficulty with the decision or task – you could get help or advice. Second, try breaking a task into smaller, more easily achieved steps. Third, try allocating a time to the unwelcome task, preferably followed by something enjoyable, for example: ‘I will do this task between 10.30 am and 12.30 pm before lunch with Peter tomorrow’. But generally, procrastination is a habit and requires self-discipline to overcome it.

Travel is a serious waster of time if there are alternative ways of accomplishing a goal. There is little point in working evenings and weekends so that you can spend your days on the train or the motorway. However, when travel is essential, a long journey by train or plane or other form of public transport can provide uninterrupted time for you to discuss an important matter with a colleague, or to read or think. Technology can allow people to carry on with many normal activities while travelling. It can also be used to avoid unnecessary travel.

Like your other scarce and expensive resources, your time needs to be planned and budgeted to make effective use of it. Time planning is itself time-consuming and routine. But, like many routines, it can help to reduce pressure by reducing the uncertainty in your day, and thus lower the stress associated with uncertainty and lack of control.

Activity 3 Stresses and actions

This activity is designed to identify one main pressure or stress in your work as a manager and what you could do about it. Consider all the sources of pressure and stress covered in sections 6 to 9. Identify just one that currently affects you most, and one action that you can take to reduce it. Say how you could carry out this action. When you are deciding on what action you will take, remember the demands and constraints that will restrict the choices you have. If you find that you have identified a pressure or stress about which you can do nothing, or not easily, then select one that you have more influence or control over. (You might discuss with your line manager the major pressure you can do nothing about.)

The major stress factor in my work:

What I will do about it:

How I will do this:

Comment

It is likely that your responses to the activity focussed on the last two readings, and possibly the last one of all. The kinds of pressures set out in Section 6 are easier to recognise than to deal with. Time management issues, covered in Section 9, are often easier to deal with.

If you were now to review your course activities you would see that you have created a profile of your job:

the roles you perform (Activity 1)

the demands of the job and the constraints that limit your choices over how you carry out your task, when and how (Activity 2)

one important aspect of your job that creates most pressure or stress (this activity).

At the same time, you have planned an action that you can carry out to improve your effectiveness.

Conclusion

This free course, Managing and managing people, provided an introduction to studying Business & Management. It took you through a series of exercises designed to develop your approach to study and learning at a distance and helped to improve you confidence as an independent learner.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course B628 Managing 1: organisations and people.

References

Acknowledgements

Course image: Dean Hochman in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Licence.

Figure 1.1 Management Standard Centre (2008) ‘Structure of the standards’, Taking Management and Leadership to the Next Level, Management Standard Centre

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University