Roaring Twenties? Europe in the interwar period

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 19 April 2024, 11:07 PM

Roaring Twenties? Europe in the interwar period

Introduction

It’s rather sad, to belong as we do, to a lost generation. I’m sure in history the two wars will count as one war, and that we shall be squashed out of it altogether, and people will forget we ever existed.

So said Linda, chief protagonist in Nancy Mitford’s bestselling and semi-autobiographical novel The Pursuit of Love, published at the end of the Second World War in 1945. It is likely that Linda’s reflections, made while taking shelter from the war on her family’s estate, matched the ponderings of the author. Like Linda, Mitford and her five sisters were Bright Young Things of the 1920s (men and women of the upper and upper-middle classes who came of age during or just after the First World War and enjoyed a bohemian and carefree lifestyle), who subsequently became deeply embroiled in the political polarisations of the 1930s. One sister, Diana, eloped with and married Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists, at the home of Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, while another, Jessica, eloped with the socialist journalist Esmond Romilly, and together they travelled to Spain to assist in the war against General Franco. Of course the Mitford sisters and other Bright Young Things did not become a lost generation – instead they rose to prominence in the popular memory of the ‘Roaring Twenties’.

However, the Mitford quote captures a second, important element in our understanding of the interwar years in Europe: the way in which war has hung so heavily over the period, as even the term, ‘interwar’, so commonly used by historians, implies. And because of this, in the literature on interwar society, we are often presented with two competing narratives: one of hedonism and frivolity, as a new generation, having been exposed to the horrors of modern war, threw off the shackles of tradition to embrace new pleasures in an almost apocalyptic manner; and one of pessimism, in which European civilisation was perceived to be in crisis, as society was plagued by discontent and political extremism, and war seemed perpetually on the horizon. The long hold of these narratives is demonstrated by the publication only eighteen months apart of two books on British society in the interwar period: Martin Pugh’s We Danced All Night (first published in 2008) and Richard Overy’s The Morbid Age (first published in 2009).

At the heart of both of these narratives is an attempt to explain the experience of modernity in Europe during the interwar years. You will recognise some features of modernity in this course – for example, the increasing visibility of, and new rights granted to, women, and the promotion of emerging technologies – as well as some of the tensions which modern life spawned.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course A327 Europe 1914-1989: war, peace, modernity.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand ‘modernisation’, ‘modernity’ and ‘modernism’ and how they relate to each other

understand modernity in interwar Europe

understand the main historical debates about society and culture in interwar Europe, in particular a sense of the patterns of change and continuity, and the extent to which any change can be attributed to the First World War

interpret visual sources, use data in tables to construct arguments, and summarise historiographical review articles.

1 Modernism

It is worth spending a moment now to untangle some of the terms that will be used explicitly in this course and that you will regularly encounter in readings on interwar society.

First, ‘modernisation’, which is a process of evolution, by which early modern and pre-industrial societies are transformed into modern societies through industrialisation, urbanisation, rationalisation, secularisation and the widening of the political community. Most historians suggest that modernisation began in Europe during the eighteenth century (Cocks, 2007, pp. 27–8), continued throughout the nineteenth and reached maturity in the twentieth.

Second, ‘modernity’, which is the experience of modernisation, an articulation of feeling modern or a sense that a break with the past has occurred, which is expressed in either positive or negative terms (or even both simultaneously). Historians have argued that there is no one moment of modernity in the 200-year period from c.1750 to c.1950; instead, there are multiple moments of modernity, which often occur in particular sites. However, a number of historians have highlighted the period 1880–1940 as a particularly important moment of modernity across Europe (Rieger and Daunton, 2001, pp. 1–4).

Third, ‘modernism’, an artistic movement that flourished in Europe from the late nineteenth century through to the interwar years. Many historians have argued that, as a narrative of change produced by an artistic elite or avant-garde, modernism had little to do with wider social change. However, modernism permeated European society more generally through the modernist architecture of new social housing projects, and the use of modern art and design by a range of political movements on the right and left (including the Republican government in Spain and the Fascists in Italy). If ordinary people were not conversant with modernism, many, especially in urban environments, were aware of it. We will not look at modernist art in any great depth in this course; however, we will touch upon it as part of the broader experience of modernity.

We will look at a number of specific features that suggest that the interwar period was a distinctive and important moment of modernity: shifts in demographics; the character of modern urban life; new forms of mass media; changing lifestyles of women; and the increasingly interventionist approaches to managing the health and welfare of modern populations. The way in which we have separated these features is artificial. For example, shifts in demographics and changes in the lives of women shaped health and welfare policies; the mass media was a vehicle through which to debate change, but also a tool to promote it; and the experience of all these features of modern life was arguably most intense within the urban environment. Two issues, derived from the historiography, will shape our assessment of these features:

- The role of the First World War in the experience of modernity – was war an agent of social change? Or did it represent an interruption to a set of inevitable developments?

- The tensions inherent in the experience of modernity – were these felt more keenly in some sites as opposed to others? How did pro- and anti-modern discourses relate to each other?

2 Modern populations

Rosalind Crone

Not everyone in Europe would have experienced the interwar period as a time of great social change, or ‘modernity’. This is particularly evident when we look at some broad demographic data from across the continent.

| State | 1900/01 | 1910/11 | 1920/21 | 1930/31 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | n/a | 6648 Footnotes 1 | 6426 | 6672 |

| % in major cities | n/a | n/a | 29 | 28.1 |

| Belgium | 6694 | 7424 | 7406 | 8092 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 13.8 | 13.8 | 17.5 |

| Bulgaria | 4338 | 4338 Footnotes 2 | 4847 | 6305 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 2.4 | 3.2 | 4.6 |

| Czechoslovakia | n/a | 13599 | 13612 | 14730 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 1.6 | 5 | 5.8 |

| Denmark | 2450 | 2757 | 3104 Footnotes 3 | 3551 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 20.3 | 18.1 | 21.7 |

| Estonia | n/a | n/a | 1105 | 1122 |

| % in major cities | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Finland | 2656 | 2943 | 3148 | 3463 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| France | 38451 | 39192 | 38798 | 41228 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 12.2 | 12.6 | 11.9 |

| Germany | 56367 | 64926 Footnotes 4 | 63181 | 66030 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 14.3 | 18.3 | 21.4 |

| Greece | 2434 | 2632 | 5017 | 7201 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 12.3 | 9.4 | 9.6 |

| Hungary Footnotes 5 | n/a | 7615 | 7990 | 8688 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 11.6 | 14.8 | 11.6 |

| Ireland | 4459 | 4390 | 2972 Footnotes 6 | 2963 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 6.9 | 13.4 | 14.1 |

| Italy | 32475 | 34671 | 36406 Footnotes 7 | 41177 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 10 | 11.3 | 12.7 |

| Latvia | n/a | n/a | 1596 | 1951 |

| % in major cities | n/a | n/a | 17.9 | 19.4 |

| Lithuania | n/a | n/a | 2116 | 2597 |

| % in major cities | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Luxembourg | 236 | 260 | 261 | 300 |

| % in major cities | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Netherlands | 5104 | 5858 | 6865 | 7936 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 21.9 | 21.9 | 22.3 |

| Norway | 2240 | 2392 | 2650 | 2814 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 10.2 | 9.7 | 9 |

| Poland | n/a | n/a | 27177 | 32107 |

| % in major cities | n/a | n/a | 5.8 | 6.2 |

| Portugal | 5423 | 5958 | 6087 | 6826 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 7.3 | 8 | 8.7 |

| Romania Footnotes 8 | 5957 | 7235 | 15635 | 18057 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 4.7 | 2 | 3.5 |

| Russia/USSR | 126367 Footnotes 9 | n/a | 136900 | 170467 |

| % in major cities | n/a | n/a | 3.5 | 4.5 |

| Spain | 18594 | 19927 | 21303 | 23564 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 7.9 | 9 | 9 |

| Sweden | 5,137 | 5522 | 5905 | 6142 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 9.2 | 10.5 | 12.1 |

| Switzerland | 2315 | 3753 | 3880 | 4006 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 6.6 | 6.8 | 9.3 |

| Great Britain (excl. Ireland) | 37000 | 40831 | 42769 | 44795 |

| % in major cities | n/a | 30.7 | 30.4 | 31.4 |

| Yugoslavia | n/a | n/a | 11985 | 13934 |

| % in major cities | n/a | n/a | 1.8 | 3.3 |

Footnotes

Note: Not all countries held a census in 1900 or 1901, and in this case data is taken from the closest census to these years. Also, in the case of Russia, there was no census taken at or near 1910/11. Back to main textFootnotes

Footnotes 1 This is the population of the geographical area which would be the Austrian Republic after the First World War. Back to main textFootnotes

Footnotes 2 Between 1910 and 1920, there were several boundary changes, including the loss of Southern Dobrudja to Romania and the gain of rather larger territories from Turkey. Back to main textFootnotes

Footnotes 3 In 1921, part of Schleswig was acquired from Germany. This is not counted in the data for 1920/21 but is counted in the data for 1930/31. Back to main textFootnotes

Footnotes 4 Territory ceded after the First World War is included in the data for 1910/11 but not for 1920/21. Back to main textFootnotes

Footnotes 5 Only population in territory that constituted the post-Trianon state (that is, after territorial adjustments made in the Paris Peace Settlement) is counted. Back to main textFootnotes

Footnotes 6 Post-partition population, so not including Northern Ireland. Back to main textFootnotes

Footnotes 7 Not including territory gained as a result of the First World War. Figure for 1930/31 does include this territory. Back to main textFootnotes

Footnotes 8 Romania acquired territory as a result of the Balkan wars and the First World War, which is counted in the relevant figures. Back to main textFootnotes

Footnotes 9 The population of the areas of the former empire excluded from the USSR was 21,734 in 1897 (excluding Finland).Activity 1

Look at Table 1 and answer the following questions:

- Can you see any broad trends in the data on the populations of individual countries across Europe?

- What impact might the First World War have had on the presence or absence of any trends?

Specimen answer

- It is apparent that not every country has population data from the period before the First World War. Mostly this is because these countries only came into existence as separate states as a result of the Paris Peace Settlement. In all those countries for which data is available (with the exception of Ireland, whose population fell in the 1920s and 1930s as a result of partition and high emigration), the population grew over the period 1900–30.

- The impact of the First World War is noticeable in some cases. For example, the populations of Austria, Germany and France all experienced a slight decline (in the case of Austria, this is a real decline as the pre-1920/21 population is only that of regions that formed the postwar, or Trianon state; also, it is important to note that Germany lost territory at the end of the war, which is not allowed for here). However, all three countries had recovered and exceeded prewar population levels by the 1930s.

Discussion

Even though the population of Europe continued to increase after the First World War, you might have noticed that the rate of growth was much higher in some countries and regions than in others. Generally speaking, populations of countries in the east and south of Europe tended to grow at a faster rate than those of the north-west. The slow growth of the latter is indicative of a decline in the birth rate in those countries, due in large part to the active limitation of family size. Starting with the upper classes and moving slowly down the social scale, parents chose to limit the numbers of their children. Whereas large families with four or more children were common across Europe at the turn of the century, in the interwar years the presence of such families declined in western Europe (for example, the average number of children born per marriage in Germany dropped from 4.7 before 1905 to 2 in 1925–29), a trend that both intensified and spread to southern and eastern Europe after 1945 (Ambrosius and Hubbard, 1989, p. 23; Usborne, 1992, p. 33). Anxieties about population growth before 1914 were exacerbated by losses of the First World War – around 1.3 million French, 2 million German and 750,000 British soldiers died in the conflict. Not only was there a sharp decline in the birth rate during the war, but recovering birth rates in the interwar years never again reached levels seen in the nineteenth century. However, some historians have argued that images of a postwar cohort of spinsters in western European countries were often the products of population panics and did not necessarily reflect reality (Pugh, 2009, pp. 124–7).

| State | City | 1910/11 | 1920/21 | 1930/31 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Vienna | 2031 | 1866 | 1874 |

| Czechoslovakia | Prague | 224 | 677 | 849 |

| Germany | Berlin | 2071 | 3801 | 4243 |

| Belgium | Brussels | 720 | 685 | 840 |

| Bulgaria | Sofia | 103 | 154 | 287 |

| Greece | Athens | 167 | 301 | 453 |

| Russia | Moscow | 1533 | 1050 | 2029 |

| Yugoslavia | Belgrade | 91 | 112 | 267 |

| Poland | Warsaw | 872 | 931 | 1179 |

| Italy | Rome | 542 | 692 | 1008 |

| Netherlands | Amsterdam | 574 | 642 | 752 |

| Hungary | Budapest | 880 | 1185 | 1006 |

| France | Paris | 2888 | 2907 | 2891 |

| Great Britain | London | 7256 | 7488 | 8216 |

| Denmark | Copenhagen | 559 | 561 | 771 |

Footnotes

Note: Warsaw was part of the Russian empire before the 1920s, and Belgrade was part of Serbia before the 1920s.Activity 2

Look at Tables 1 and 2 and answer the following questions:

- Looking at the populations of the major European cities, can you see any notable trends? Did the First World War have any impact on these cities?

- From the data in the tables, do any countries stand out as being more urbanised than others? Are there any notable trends to discuss?

Specimen answer

- In almost every city listed in Table 2, the population increased over the period 1910–30. However, Paris, Budapest and Vienna are the exceptions to this trend: in Paris the population declined each decade, but the small extent of that decrease suggests a fairly stable population; Budapest grew between 1910 and 1920, but then experienced a small decrease by 1930. These figures also suggest that the greatest increases in population happened during the 1920s. For the most part, the impact of the First World War was marginal: some cities in countries with a direct experience of combat found their populations decreasing slightly, but this was more than made up for after the war. However, Vienna’s population decline could be said to have been directly related to the war, as the city suffered in the 1920s because it lost its status as the capital of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

- Even if the general trend was towards urban expansion in the interwar period, urbanisation was not the dominant experience in all European countries. The data in Table 1 on the populations of the major cities for each country show that European states with larger urban populations tended to be located in north-west Europe.

It is important not to equate the process of urbanisation with industrialisation. A large number of those states in eastern Europe had expanding urban populations in the interwar years yet were not industrialising at any significant pace. In the 1930s, when the agricultural labour force in Britain had shrunk to 5 per cent of the population, and in Germany, France and much of Scandinavia to around 20 to 30 per cent, in eastern Europe, and particularly in the Balkans, agriculture continued to dominate, employing between 50 and 75 per cent of the populations (Wasserstein, 2009, p. 213). Derek Aldcroft has described the periphery of states stretching from eastern Europe around the rim of the Mediterranean (for example, Greece, Spain and Portugal) as Europe’s ‘third world’ during the interwar years. These states tended to be dominated by an antiquated and inefficient agrarian sector based on peasant self-sufficiency, smallholdings, overpopulation on the land, primitive farming techniques, lack of capital investment and poor education. The general poverty of the countryside meant that the market for industrial goods was small and growth discouraged. For example, 40 per cent of Hungarians were poor peasants who lived at a minimum level of subsistence and considered the most basic items such as shoes and clothes a luxury (Aldcroft, 2006, pp. 175–7). R.J. Crampton adds that often any surplus money was spent on family, religious or community festivals, and not reinvested in agriculture or used to purchase modern industrial goods (1994, p. 35). Thus it would seem that we could hardly describe society in these countries as ‘modern’ (see Figure 1).

This photograph shows four people, two men and two women, harvesting wheat in a field in Hungary. All four people have their backs to the camera, the wheat stands tall in front of them, and harvested wheat lies behind them. Their arrangement is as follows, from left to right: woman, man, woman, man. Both men, standing tall, are using scythes to cut the wheat, while both women, bent over, are collecting the cut wheat. There are no other agricultural tools or machinery in the photograph. The people are all dressed in peasant attire. In particular, the women wear long, ankle-length skirts and long head scarves.

However, some historians have argued that the backwardness of life in these states has been overplayed. For instance, Robert Bideleux and Ian Jeffries caution us not to paint too bleak a picture of interwar eastern Europe, quoting the observations of Hubert Hessell Tiltman in his Peasant Europe, published in 1934:

The Bulgarian people have been ‘lifted off the floor’ … The poorest Bulgarian peasant today generally has his land, his house, some pieces of furniture and his self-respect … And with this psychological transformation the health of the people has improved. The death rate, though still high, is falling … The peasantry live in modern two-roomed dwellings, often built of designs supplied by the state, and their animals are housed separately. The earth floors have been replaced by brick and wood. There are windows that open … Many … now sleep on beds and eat sitting at tables. Separate plates for each person have replaced the old communal bowl. Electric light, even, has come to some of the villages.

This source is a helpful reminder that the process of modernisation or experience of modernity was uneven, that we cannot necessarily divide Europe into those countries which were modern and those which were ‘backward’. Prague and Krakow became vibrant hubs of modernist culture during the 1920s, attracting intellectuals from the east and exporting new ideas in photography to the west (Fischer, 2010, p. 193). Conversely, Martin Pugh states that life in rural Britain demonstrated greater continuity than change in the interwar years (2009, pp. 260–1).

3 The interwar city as a site of modernity

Rosalind Crone

In the previous section I established that while the majority of Europeans in the interwar period were not urban dwellers (though in some countries, especially in the north-west, the majority were), the process of urbanisation, already underway in most countries before the First World War, gathered pace during the 1920s. This was in part linked to economics: as Paul Lawrence has written, ‘unlike the factory industrialization of the nineteenth century [...] which had concentrated people near coalfields and water sources, the capitalism of the twentieth century favored large capital cities and commercial centers’ (Lawrence, 2005). Thus, the first half of the twentieth century witnessed the rise of the ‘metropolis’.

Many features of the modern metropolis were visible before the First World War. Electricity, urban transport networks including underground railways, large department stores and mass entertainment venues such as music halls were all visible in cities such as London, Paris and Berlin. However, after the war, electricity supply was expanded (including into the domestic environment) and rationalised (for instance, through initiatives such as the National Grid in England and Wales); music halls were joined and subsequently replaced by cinemas, dance halls and jazz clubs; existing urban transport networks were extended and new ones built to service growing numbers of commuters living in emerging suburbs; new forms of transport, notably cars, raised the tempo of city life; and the increase of white-collar employment, for women as well as men, swelled the ranks of the middle class and fuelled new levels and forms of consumerism. While municipal authorities began to focus on ‘town planning’, urbanisation and changing demographics collided with the artistic movement of modernism, generating new designs for urban living that promoted functionalism and hygiene. Finally, the city began to acquire a new dominance over rural life in many countries: it sucked in immigrants from the countryside who were in search of new employment opportunities; and new communications networks, often emanating from the city, promoted urban life and culture.

Despite the pleasures and conveniences offered by the metropolis, modern urban life was not always viewed in a positive light. In the first place this was because change was uneven – for instance, in all cities overcrowded slum neighbourhoods persisted alongside new social housing. But it was also because the experience of modernity could produce a longing for the stability associated with tradition and a lost rural idyll. As Bernhard Rieger and Martin Daunton have argued, this negativity was most strongly articulated in those cities in which the break with the past had been rapid and intense (2001, pp. 9–11). For example, cities in Germany, Italy and Russia were not only subject to rapid expansion and modernisation after 1918, but also became sites for political extremism and violence (Jerram, 2011, p. 33).

Exploring interwar Berlin

In order to get a sense of the change and continuity present in the modern metropolis, as well as the tensions created by the sense of modernity, let’s take a look at one city in more detail: Berlin.

Although Berlin was not necessarily representative of other European cities, contemporaries often wrote that that the city was representative of the experience of modernity. In the early twentieth century, Berlin had only recently emerged as a major European city. Prussian power in the process of unification had ensured that Berlin became the new German capital after 1871, and this, combined with rapid industrialisation, meant that the city already had a modern look and feel before the outbreak of the First World War. Its population had also begun to grow: it more than doubled between 1910 and 1930. Moreover, the Greater Berlin Act of 1920 recognised the sheer physical expansion of the city as a number of outlying ‘towns’ and other communities now surrounded by the urban spread were officially incorporated into the city. However, it was during the interwar years, under the shadow of defeat and the instability of the democratic experiment that Berliners experienced modernity most intensely. This modernity was viewed both positively and negatively by different groups, within and outside Germany: for some the new attractions of the city were exciting and liberating, but for others the city’s modernity was horrific, and Berlin became a symbol of modern decay.

In the following activity you will explore a map of the U-bahn system as it operated in Berlin in 1930. The ‘Untergrundbahn’ or ‘U-bahn’ was in fact an invention of the period before the First World War. Its construction began in 1897, some three decades after the London Underground but around the same time as the Parisian Métro. By the outbreak of war two lines had already opened: U1, connecting the east of the city with the west, and U2, connecting the north with the west. However the interwar years witnessed the great expansion of this network, as both U1 and U2 were extended and new lines were constructed, making journeys within the city easier, and providing more transport options for those commuting from the suburbs. (If you are particularly interested in the development of the U-Bahn network, and its relationship to other transit systems in Berlin, such as the Stadt-bahn, or S-bahn, you can take a look at the historic maps on this German transport website.)

The U-bahn map gives you the opportunity to take a short tour of the main attractions of Weimar Berlin. I have selected three stations for you to visit in order to give you a sense of the experience of modernity in the city. At some stations, you will be ‘free to roam’, by watching footage of the city from the period (namely, from Walter Ruttman’s film, Berlin: Die Sinphonie der Grosstadt, 1927); at other stations, you will be joined by Matt Frei who will offer a guided tour. Your visit to each station will also be accompanied by a short activity – you might be asked questions on the film you have just watched, or you may be asked to read a primary source document.

Your first stop will be Potsdamer Platz.

Station 1: Potsdamer Platz

Click on the link below to view the U-Bahn map. You will find a hotspot for Potsdamer Platz station. Click on the hotspot and watch the film that is in the pop-up window (please note that this film is mute). When you have watched the film, click back on your browser to return to this page.

Potsdamer Platz, the meeting point of five major roads making it one of Europe’s busiest traffic intersections, has often been held up as iconic of 1920s Berlin; though many of its physical indicators of ‘modernity’ in fact predated the First World War. For example, the most famous buildings associated with the Platz had been constructed in the late nineteenth century, including the magnificent Wertheim department store (1897), Café Josty (1880), and the food emporium, Haus Vaterland (1912). However, during the 1920s the use of these buildings came to be representative of Weimar social life and culture. Café Josty (which you saw at the end of the film) became an important meeting place for artists and intellectuals. Haus Vaterland underwent substantial renovations in 1928, and was transformed into a palace of entertainments, complete with illuminated dome. And in the early 1930s, a symbol of the modernist age, Erich Mendelsohn’s Columbus House, was added to complete the set.

Activity 3

The footage you have just seen includes scenes of not just Potsdamer Platz, but also some of the surrounding main thoroughfares.

Can you identify any indicators of modernity in these scenes that are particular to the interwar years?

Specimen answer

Ruttman’s Sinphonie is a celebration of the modern city, and it can be difficult to untangle those features in the film which are particular to the interwar years. However, I picked out two primary indicators. First, transport; specifically the appearance of cars on the city streets, and the problems that these new vehicles created for urban order. You might have noticed the policeman on the streets directing the traffic. Also, you might have noticed the continued presence of more traditional modes of transport, especially the large number of horses with carts attached. The second indicator I identified was the presence of women in the public sphere – not just the fact that there are quite a lot of women in the film walking the city streets, but that they do so unchaperoned and often with a sense of purpose. This perhaps suggests that they are on their way to work. I also took note of the fashions that many of these women were wearing, a contrast to images of women in the prewar period.

I hope you enjoyed exploring the city centre. Next, you will go to the station Onkel Toms Hütte. On arrival there, you will be joined by your tour guide, Matt Frei.

Station 2: Onkel Toms Hütte

Click on the link below to view the U-Bahn map. You will find a hotspot for Onkel Toms Hütte station. Click on the hotspot and watch the film that is in the pop-up window. When you have watched the film, click back on your browser to return to this page.

You might have noticed the peculiar name of this U-bahn station, Onkel Toms Hütte, which, directly translated, means Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In the late nineteenth century, a pub landlord named Thomas constructed small huts or cabins in his beer garden for customers to shelter in when it rained. This, combined with the popularity of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, made the play on the name irresistible. Between 1925 and 1932, the site was redeveloped, allowing for the construction of a large housing estate designed by GEHAG, a team of architects led by the famous modernist architect, Bruno Taut. Taut and GEHAG were also responsible for some of the other large housing estates you saw in the film – for example, the famous Horseshoe Estate (Hufeisensiedlung) in Britz, on the southern edge of the city.

Activity 4

To get an idea of what it was like inside these new, modern, living quarters, read Source 1, Otto Steinicke’s ‘Visit to a new apartment’, and answer the accompanying questions.

- What is the general tone of the article?

- Can you identify some of the features of ‘modern living’ which Steinicke draws to the reader’s attention?

- Given the layout of the new apartment he describes, who was expected to occupy it?

Specimen answer

- The tone of Steinicke’s article is overwhelmingly positive. He emphasises all the attractions of modern apartments compared with former city housing.

- Steinicke lists a number of features of modern urban living. Electricity and central heating are perhaps the most obvious. He also places great emphasis on improvements in hygiene. Similarly, he stresses the tidiness of the new apartments – although some residents had brought some of their old furniture with them, many had dispensed with items that tended to clutter their former living quarters, for example, knick-knacks and other superfluous and cheap ornaments.

- Steinicke describes a two-and-a-half room modern apartment. In practice, this consists of a main room (including a kitchen), a bedroom, a child’s bedroom, and a bathroom. Steinicke also tells us that there is a double bed and two small children’s beds in the apartment. It is clear that the designers intended these apartments to be occupied by a nuclear family, ideally two adults and two children. These expectations fit with what we know about demographic patterns in Europe during the interwar years.

Discussion

Also of note in this article is Steinicke’s description of the tortuous process by which the Müller family obtained their modern apartment. Although around 2.5 million modern apartments such as these were constructed during the Weimar period, the majority were occupied by the middle classes, despite the great need for housing for the lower classes identified by the Weimar government. Moreover, the 1925 census revealed that more than 117,000 people were homeless in Berlin (Wasserstein, 2009, p. 214). Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, famous districts such as Wedding, to the north east, and Hallesches Tor, within a short walk of the glittering Potsdamer Platz, remained representative of the slum-like conditions that many of the unskilled and semi-skilled urban labourers continued to live in: families were often crowded into damp and unhygienic tenements that had been rapidly put up in the late-nineteenth century to house a growing industrial workforce. The persistence of similar slums in most European cities has led historian Leif Jerram to question the apparent ‘liberty’ that urban life offered to former agricultural labourers, especially women (Jerram, 2011, p. 103). For an alternative description of living quarters in interwar Berlin, you might like to read Source 2, Christopher Isherwood’s description of the Nowaks’ house in Wassertorstrasse.

When you are ready, we will continue on our tour. Before we head back into the centre of Berlin, we will make one brief stop further down the line at Krumme Lanke, another housing estate constructed in the 1930s, which will expose you to some of the tensions of modernity.

Station 3: Krumme Lanke

Click on the link below to view the U-Bahn map. You will find a hotspot for Krumme Lanke. Click on the hotspot and watch the film that is in the pop-up window. When you have watched the film, click back on your browser to return to this page.

You will explore the competing versions of modernity offered by authoritarian right-wing regimes in more depth later in this course. However, you might like bear in mind some of the comments made about the ‘idyll’ that the Nazis were attempting to create with this housing estate as we move on to our final stop on this tour, Nollendorfplatz. Matt Frei will make some comments about the character of Berlin’s west end in the late 1920s, after which you will be shown some footage of Berlin nightlife from Ruttman’s Sinphonie.

Station 4: Nollendorfplatz

Click on the link below to view the U-Bahn map. You will find a hotspot for Nollendorfplatz. Click on the hotspot and watch the film that is in the pop-up window. When you have watched the film, click back on your browser to return to this page.

Activity 5

- Make a list of the key features of urban leisure in 1920s Berlin.

- What theme links Frei’s commentary with Ruttman’s film?

Specimen answer

- Cinema; illuminated shop windows and flashing neon lights; cabaret-style entertainment (or variety theatre) including dancing girls, acrobatic tricks, music, and other circus acts; cocktail bars; night clubs with dancing, live bands and casino entertainments; sexual freedom (including homosexuality).

- Hedonism. This is first apparent in Frei’s description of the deliberate ignorance of street violence in favour of drinking and partying. Ruttman’s pleasure-seekers also seem oblivious to all but enjoyment – most obviously, the couple getting into the cab: the sexual frisson between the two is evident by the way the man places his hand on the woman’s arm, and both ignore the plight of the poor begging boy.

Discussion

Dance halls pushing popular music, nightclubs with resident jazz bands and cinemas could be found in cities across Europe in the 1920s, but it is worth noting that in Berlin transformations in popular culture seemed to be much more extreme than elsewhere, the result of a combination of political freedom (ie, the absence of censorship legislation) and a deep sense of instability. At the same time though, those extremes were often experienced by a small minority – elements of the intelligentsia, or even tourists to the city intent on seeking out pleasures for which Berlin had acquired a reputation. As the British diplomat Harold Nicholson later wrote, ‘it was not the Berliners themselves who most frequented these palaces of delight; it was the tourists and the businessmen from Dortmund or Breslau’. Yet the perception of cultural extremity can be just as important as the reality.

Activity 6

Read the Source 3.

- Can you identify the author of this article?

- What are the problems of modernity that concern the author?

Specimen answer

- The author is Joseph Goebbels. You might already be familiar with the name, and know him as the propaganda minister under the Nazi government from 1933. In 1926, Goebbels had become the Gauleiter (regional head) of the Nazi Party in Berlin-Brandenburg.

- For Goebbels, several features of modernity – cosmopolitanism, cultural openness and the rise of the political left – have led to great moral decay.

Activity 7

For now, I want to end this tour with a hint of what was to happen next, through a little case study of the famous erotic dancer of 1920s Berlin. Watch the following film:

Transcript: Berlin nightlife

[MUSIC]

[MUSIC]

[MUSIC]

[MUSIC]

4 Mass media and the transformation of popular culture

Rosalind Crone

Those living in the city, and increasingly those living outside the city, were exposed to new forms of mass media in the interwar period, which sparked a transformation in popular culture. Given that cinema and radio were regarded by many as forms of entertainment, you might well ask why I have applied the label ‘popular culture’ rather than ‘leisure’. First, this is because the term ‘leisure’, and its use by historians, suggests that people in the past neatly divided their time into periods spent in work and in relaxation. Work hours became shorter and more regulated for many (for example, those in industrial and white-collar employment) across Europe in the first decades of the twentieth century, but there were several groups for whom the segregation of work and leisure time did not apply, including women and the unemployed. Second, the term ‘popular culture’ highlights the relationship between these phenomena and the way in which its consumers saw the world around them. Third, it is necessary to distinguish between these popular entertainments, which were available and often patronised by all, and the cultural products of the intelligentsia, often referred to as ‘high culture’ and typically inaccessible to many ordinary people because of their price or their form. (For instance, we could group a substantial amount of the output from the artistic movement of modernism, referred to earlier in this course, in this category.) However, we would do well to remember too that the participation of ‘cultural elites’ in popular culture meant that these entertainments and the themes or messages that they promoted had some impact on the creativity of the avant-garde.

In what ways was popular culture transformed during the interwar years? First, and most obviously, it was transformed by technology, so that it is possible to refer to a process of modernisation at work in the entertainments enjoyed by the people. Radio was a new invention; film had existed before the First World War but took off dramatically after 1918, and the introduction of sound further increased its appeal in many countries during the 1930s. Popular culture was thus experienced in new ways. But be aware that the new media did not always replace older entertainments that survived from the nineteenth century. Second, the growth of the middle class, combined with an increase in the spending power of many urban workers and changing methods of production and dissemination, which drove down prices and increased the ability to cater for large audiences, led to the emergence of ‘mass’ audiences for many phenomena. The 1920s and 1930s formed a key moment in the development of mass culture – entertainment made for the people but not by the people. However, as you will see below, you should be wary of the term ‘mass culture’ because audiences often continued to be fragmented in various ways by age, class and gender, and audiences, as paying consumers, continued to have some role in the creation of popular culture. The authenticity of popular culture was challenged but not eradicated. Similarly, it is worth noting the impact of the rise of modern totalitarian regimes, especially those that publicly decried modern forms of leisure and promoted traditional lifestyles. As was evident in the material on modern Berlin that you explored in Activity 3, there was no clear anti-modern rhetoric: instead, regimes such as Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Soviet Russia recognised the possibilities offered by mass media in their pursuit of mass politics, particularly for propaganda purposes.

The politics of production

The medium of film came into existence in the late nineteenth century and by 1914 had developed from a fairground attraction into a popular, if often low-brow, entertainment housed in purpose-built cinemas. But it had found commercial success, becoming a huge international undertaking. Before the outbreak of hostilities in 1914, international production and distribution were dominated by the French, British and Italian film companies (Chapman, 2001, p. 174). Although war disrupted trade across Europe, its effects on each local film industry varied greatly. In Britain and France, film production declined rapidly during the war years, and those cinemas that remained open to the public filled their programmes with Hollywood imports. In contrast, the isolation of Germany and Russia encouraged growth in local film production. In Russia, the vibrancy of local production was relatively short-lived, as it was interrupted by revolution in 1917 and failed to attract the necessary audiences during the 1920s. However, during the 1920s, Germany became the largest European film producer: in terms of its local market, German film companies produced at least as many films as were imported (Laqueur, 1974, p. 230). During the interwar years, as the dominance of Hollywood productions in Europe increased, some governments attempted to promote their national film industry: while the British government introduced a quota forcing cinemas to show a set number of local films, in Germany and France the importation of foreign films was limited in 1925 and 1931 respectively, and in the Soviet Union film imports were stopped altogether in 1929.

While film production was conducted by private companies on an international scale, radio broadcasting, by contrast, was typically national and controlled by the government. Wireless telegraphy and telephony had advanced significantly during the two decades before the outbreak of war; during the war, radio-telephony was used as a method of communication on the battlefield and amateur wireless activities were, as far as possible, brought under state control (Briggs, 1961, p. 39). Even if war had helped to develop wireless technology and increase the power of the state, broadcasting was predominantly a new feature of interwar society in Europe. With their established monopoly over the airwaves through licensing systems governments across the continent had the power to determine who broadcast signals as well as who received them. By 1938, ‘of the thirty European national broadcasting systems in existence, thirteen were state owned and run, nine were government monopolies, four were directly operated by governments, and only three were privately-owned’ (Aldgate, 2001, p. 167).

Content

The politics of production shaped the content of the new mass media. The rise of American imports across Europe, facilitated in the 1920s by the fact that film was ‘silent’ (that is, in terms of dialogue, but music was typically added at viewing venues), did much to determine popular taste. The popularity of American films in Poland soared during the 1920s – by 1926 they constituted 70.6 per cent of all films shown. However, the introduction of sound led to a 30 per cent decrease in cinema attendance – Polish audiences wanted films in their own language but local production remained limited (Haltof, 2002, pp. 10, 24). Glamorous Hollywood feature films offered escapism, which many viewers desired but which many local production companies eschewed, especially those employed by the state to peddle propaganda. Thus, in France, where the Ministry of Agriculture attempted to use film to educate French farmers on progressive farming techniques, the only way to attract audiences to the village halls, bars and cafes where film projectors had been installed to deliver these messages was to include in the package of reels purely entertaining material such as comedies donated by commercial companies (Levine, 2004). Anti-censorship laws in Weimar Germany encouraged a healthy degree of experimentalism in the production of local films, though much of this proved to be apolitical, perhaps because producers were aware of the need to make money (Laqueur, 1974, p. 181). In Britain, where large picture palaces owned by three companies – Odeon, Gaumont-British and Associated British Cinemas – dominated the market by the 1930s and treated viewers to a near-exclusive diet of American blockbusters, concerns were raised by cultural elites that these films engendered apathy among the working classes while corrupting English speech and promoting gangster life (Beaven, 2005, pp. 187–90).

Perhaps it is little wonder then that when governments had the ability to control mass media they took to the task with great energy, as was the case with radio broadcasting. In Germany, radio broadcasting was ‘to be above party politics – unlike so many of Germany’s great and influential newspapers and other printed periodicals – and it was not to be subject to the kind of international influence that challenged the independence of the German motion picture industry throughout the 1920s’ (Führer, 1997, p. 724). In Britain, Germany and even Russia the radio was regarded as a tool for the education and enculturation of the masses. During the late 1920s, Soviet radio experimented with the establishment of a ‘university of the air’, transmitting educational broadcasts to around 80,000 pupils (Stites, 1992, p. 83). However, in Britain the insistence of John Reith, director general of the BBC, on a schedule dominated by discussion programmes, lectures, plays and classical concerts encouraged many, and especially working-class, listeners to tune in to the new commercial stations broadcast from the continent in the early 1930s – Radio Normandie (1931) and Radio Luxembourg (1933) – which satisfied the desire for popular music. The BBC’s attempt at compromise, scheduling ‘hot music’ every night from 10.30 pm until midnight, did not please everyone, as this letter from Beryl Heitland to the editor of the Musical Times in September 1933, demonstrates:

As things are, it is surely time that the official B.B.C. heard a Neighbour’s Radio Concert in a big block of modern flats on a warm evening, or in a reasonably crowded street of suburban gardens. Now, are we all to be content to be plagued till midnight, night after night, by the thrum-thrum, and unutterably dreary whine and moan of the jazz band through walls and windows – because it pleases the proletariat? Who will invent for us some device which will keep us sacrosanct from other people’s choices in radio? Please tell us that, Messrs. B.B.C., and till then, marvel not that lovers of music and of a modicum of plain silence lift up their standard against the arch-fiend, noise.

Reception

Activity 8

Compare Beryl Heitland’s letter to the Musical Times in 1933 (quoted at the end of the previous section) with the extract below, from an autobiography written by two sisters describing their childhood in a working-class district of Lincoln. What are the major differences in the experience of listening to the radio which each source describes?

It is not easy now to remember what life was like before radio and television and, certainly, the coming of the wireless made a great deal of difference to us. It was not just the listening that mattered it was also the talking about it afterwards.

[…]

Mother looked down her nose at those ‘who had it on all day’ and we were encouraged to choose our programmes and none was allowed to be switched on while homework was in progress. Mother always listened to the Morning Service and we all kept quiet during Children’s Hour and the News. We sometimes listened to plays and nearly always to Variety programmes of the Music Hall kind.

[…]

We listened of course to all the outside broadcasts of the great events and Mother loved listening to Howard Marshall’s cricket commentaries; a taste she never lost. We were never much interested in racing apart from the commentaries on the Grand National and the Derby but we did listen to Wimbledon in the heady days of Fred Perry and Bunny Austin and Dorothy Round. And sometimes we listened to football and rugby on the radio. These last were best done with a Radio Times picture of the pitch divided into numbered squares to help the listeners to know just where the action was taking place. Over the hubbub of the cheers and shouting and the excited account of the commentator would come a calm and clinical voice saying ‘Square One’ or ‘Square Four’ and you knew just where you were!

Specimen answer

The first major difference that I could spot was the family- and home-centred experience of listening in the autobiography, compared with the (unwanted) communal experience in Heitland’s letter. For Heitland the radio was background music, but for the Skinners radio programmes captured the household’s full attention, and were events to be talked about or even sometimes part of a multi-media experience involving the Radio Times. Heitland was implying that the dance music was put on solely to appeal to working-class people (‘the proletariat’): the Skinner family enjoyed the ‘improving’ elements of radio output as well as the ‘Music Hall’. Mrs Skinner did seem to share some of Heitland’s snobbery though – feeling superior to ‘those who had it on all day’.

Discussion

It’s easy to find evidence of class-based prejudices like Heitland’s about the social impact of ‘working-class’ culture – but we mustn’t forget that within social classes, people like Mrs Skinner also had opinions about what was the proper way to live. Notions of respectability and appropriateness could cut across class boundaries, and they were often linked to opinions about which forms of popular culture were the most acceptable.

Let’s tease these issues out a little more to gain a full appreciation of the experience of the radio during the interwar years. Patterns and practices of listening varied between and within social classes and they varied over time. Broadcasts at the start of the 1920s were most often received on crystal sets through a single pair of headphones when the listener was within a relatively short distance – i.e. about 15 kilometres – from the transmission tower. Over the next few years, valve sets (such as that in the photograph), which could be plugged in to the mains supply of electricity, emerged and eventually, by the end of the decade, these came with loudspeakers. As these valve sets were more sensitive, the geographical reach of broadcasting was extended. They were also expensive, at least in the early years, and those who wanted to listen were also required to purchase an annual licence.

But these financial considerations did not prevent the working classes, or those based in more rural locations, from tuning in. The licensing statistics tend to obscure the sheer numbers of those with access to radio. Although in both Russia and Italy private ownership rates were low, many people listened to broadcasts in public spaces: in Russia programmes were broadcast over loudspeakers, while in Italy radios were commonplace in cafes and factories (Wasserstein, 2009, p. 235). In contrast, Britain and Germany boasted higher rates of private ownership – in 1932, 4.3 million licences were issued in Germany and 5.2 million in the United Kingdom – but especially in the 1920s, when costs were still significant, these figures failed to capture a large number of people listening in ‘illegally’ (Führer, 1997, p. 731; Pegg, 1983, p. 7). Crystal sets, for example, could be bought as kits and constructed at home. One woman from Warrington in north-west England, interviewed as part of a local history project, remembered that she used to buy radio parts for her husband:

When it was his birthday, or when Christmas came, I used to give him parts for his wireless, d’you see. I’d put fourpence away every week to save up to get him the bits he was after. All the family – not just me – bought him these different parts for it and he built it up himself.

As suggested by the interviewee, men and women could experience radio differently. One British social commentator remarked that ‘it seems to women that the last thing men want to do with their wireless set is to listen in. They want to play with it, fiddle with it incessantly’ (quoted in Beaven, 2005, p. 203). Especially with the addition of loudspeakers on receivers, listening was the primary experience of women, many of whom tuned in while completing household tasks, challenging the boundaries between work and leisure time. Some have argued that this use of the radio, as background noise, was also distinctively working class; in contrast, the middle-class family would tune in at specific times and listen attentively.

Age, gender, class and geographical location similarly fragmented the superficially homogenous cinema audiences. In many countries across Europe, cinema-going reached its heyday during the interwar period. Yet the statistics often bear this out in an unexpected way. If we take Britain as our example, which was said to have the highest rate of cinema attendance, there were approximately 1,600 cinemas in 1910, around 4,000 in 1921 and just under 5,000 in 1939 (Jancovich et al., 2003, p. 85; Pugh, 2009, p. 229). On the surface, these statistics suggest that, if anything, the cinema craze slowed down during the interwar years. But what they don’t tell us is that cinema construction had changed: in 1912 the average cinema had 600 seats; by the late 1920s and 1930s, new cinemas with 2–3,000 seats were being built. We might expect that patronage by the majority of the large cinemas that were under the management of three companies would have homogenised the cinema-going experience, but historians have shown that this was not the case. At least three different types of cinema, which attracted different clienteles, existed in British cities: prestigious city-centre cinemas, which showed first-run films and were expensive; new, luxurious suburban cinemas, attracting the local middle-class and skilled working-class families; and cheap, inner-city cinemas, located in older working-class neighbourhoods and often referred to as ‘fleapits’ (Jancovich et al., 2003, p. 87). Moreover, even in those cinemas that boasted a socially mixed clientele, ticket-pricing strategies ensured that audiences were segregated by class (Richards, 1984, p. 15).

Corey Ross has argued that similar distinctions existed in the cinema audiences of interwar Germany. Middle- and working-class Germans not only patronised different cinemas, but their behaviour within these establishments represented a great contrast: working-class patrons ‘came and went at any time during the screening, frequently ate, smoked and drank as if they were at home’, and shouted, laughed and roared through the films (Ross, 2006, p. 170). The cinema also offered different experiences for the young and more mature: while many youths found in the cinema a convenient location to pursue courtship, for many married women the cinema expanded available leisure opportunities as, unlike the public house, this was a venue she could respectably attend with her husband or even alone (Beaven, 2005, p. 193). Finally, the location of cinemas, primarily in urban centres, did limit the extent of the experience of modern cinema-going. Levine (2004) has shown how cinema could be exported to the countryside of France. In contrast, Ross has argued that, as only 1,462 of the 63,507 towns with populations under 10,000, in which over half of all Germans lived, had any cinema at all, this medium could in fact widen the cultural gap that existed between urban and rural populations (2006, p. 162).

5 The ‘New Woman’ – myth or reality?

Rosalind Crone

For contemporaries, both the experience and challenge of modernity was prominently encapsulated in the motif of the ‘New Woman’. By the 1920s, women in many countries had not only won the right to vote, but were also moving into new occupations and choosing to wear ‘rational’, or at least much less restricted, garments. These developments seemed to pose a challenge to the traditional role of women as homemakers in the private sphere, especially at a time when anxiety about population growth and birth rates was rife. For historians writing since the rise of women’s history in the 1960s, debate has focused on whether or not the New Woman actually existed. In their discussions, the First World War has acquired a central place. Discussions have referred to the range of occupations that women entered during the war, as well as the challenges that war presented to traditional conceptions of both masculinity and femininity. However, the extent to which war generated lasting change has been disputed by successive generations of historians.

Activity 9

Read Source 4, Adrian Bingham’s article ‘“An era of domesticity?” Histories of women and gender in interwar Britain’. Try to summarise the main trends in the historiography on the New Woman, or, in other words, to isolate the main groups of historians and identify their primary contribution to the debate about the New Woman.

Specimen answer

When I read this article I identified three main trends in the literature on the New Woman since the 1960s:

- During the 1960s and 1970s, a group of historians (including Arthur Marwick and David Mitchell) championed the notion that the First World War had ushered in significant changes to the lives of women, predominantly in the form of enfranchisement and widening employment prospects.

- However, during the 1980s another group of historians – Gail Braybon, Dierdre Beddoe, Harold Smith and Susan Kent – challenged this by presenting evidence of a backlash against women. Even if women had enjoyed limited freedoms in work and social life during wartime, these were quickly removed once war had ended, under a ‘prevailing atmosphere of domesticity’.

- By the late 1990s, a third group of historians had emerged (e.g. Cheryl Law, Caitriona Beaumont, Claire Langhamer and Birgitte Søland) whose research into other aspects of social activity revealed substantial limits to the backlash thesis of the 1980s. These historians argued that the 1920s formed an important moment of modernity, marked by changing expectations and greater opportunities for young women (note that they introduce an important differential here, which I will refer to again below). Moreover, they placed great weight on the importance of cultural representations of femininity, or the proliferation of images of the New Woman, which, even if not a strict reflection of reality, had significance as a way of asserting change.

Discussion

Although it is not made explicit in this article, it is important to note that the last group of historians that Bingham identified (and of which he is a member) have largely shifted their focus away from debating the impact of the First World War on the lives of women. Let’s take a moment to consider this further. It could be argued that the second group of historians saw the First World War as a blip, an interruption to patterns of continuity in women’s lives as wives and mothers; after the war, things went back to normal. By sidelining the First World War, the third group of historians also suggest that the event might have been a blip, but one that interrupted a series of gradual changes present in the decades leading up to war and gathering pace in the early 1920s. This is especially noticeable in the use of the term ‘New Woman’. It is a useful shorthand to describe a process occurring across Europe in the interwar period. However, in France and Britain the term ‘New Woman’ has a much longer pedigree. It was used from the late nineteenth century to describe a small minority of mostly wealthy women who were able to live with some independence, dabble in careers that shocked their families, and experiment with some new fashions of rational dress. These ‘New Women’ were both related to and distinct from the ‘flapper’ and ‘garçonne’, or ‘Femme Moderne’ of 1920s’ Britain and France, as well as the ‘Neue Frau’ of interwar Germany. In other words, it is important to try to untangle changes that occurred as a result of war from developments that had begun before it.

Modern fashion in the making of modern women

As you might have picked out from Bingham’s article, early feminist historians tended to seek indicators of change that they recognised from their own experiences of campaigning for women’s liberation, including employment opportunities, shrinking wage differentials, enhanced legal status and sexual freedom (Roberts, 1994, p. 6). Perhaps unsurprisingly, they were often disappointed. In few European countries did the interwar period show significant change in these categories for women. Female enfranchisement achieved in some states was often granted at the same time as universal suffrage for men and, if anything, feminist activism in the political sphere seemed to be in decline. In most states, too, the number of employed women after the First World War was roughly comparable to the number employed before the First World War; and even if general employment statistics have disguised changes in the types of work women did (e.g. an increase in white-collar and factory employment in some countries at the expense of domestic service and agricultural labour) and a growth in the employment of young women, neither of these trends had any impact on marital rates, which remained high. Also, despite provisions made in some new constitutions (e.g. in the Weimar Constitution), women continued to be paid at rates below that of men. And, finally, any new degree of sexual freedom tended to be limited to a small minority.

However, as some historians have suggested, an alternative indicator of change can be found in new fashions that emerged for women during the interwar years. Fashion could be representative of change as well as an initiator of change. Wearing new fashions could also be a way of experiencing change. Hence fashion played an important role in the making of the modern woman. At the same time, changes in women’s fashion further expose the contradictions inherent in the discourses of modernity.

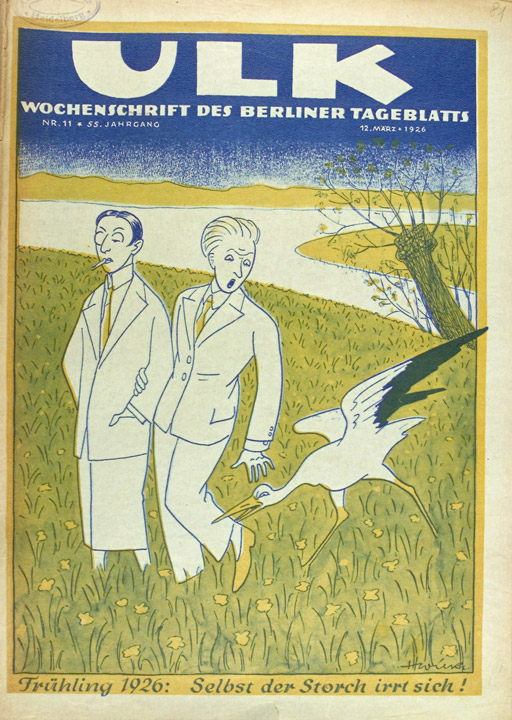

This is the front cover of the German weekly periodical, ULK. This title means ‘joke’ or ‘fun’ in German. ‘ULK’ is in capital letters across the top of the page. Directly underneath is the subtitle, also in capital letters, ‘Wochenschrift des Berliner Tageblatts’ (‘weekly magazine of the Berliner Tageblatt’ – a daily German newspaper. Underneath that is the issue number (NR. 11), 55. Jahrgang (55th year) and the date of publication (11 March 1926). Most of the cover is taken up with a drawing. It shows a man and woman walking in a green field with yellow flowers. A winding grey river is behind them. There is a short tree on the river bank on the right-hand side. New leaves are growing from its sparse branches suggesting the start of spring. In the distance, across the back of the picture, is a row of mountains, and the sky above them is a dark blue. The pose of the man and woman suggests that they are couple: the man on the right holds on to the arm of the woman on the left, who has her hand in her jacket pocket. Their dress is remarkably similar: each wears a white jacket, a yellow tie, and a white shirt. The man wears trousers, while the woman wears a long skirt or possibly three-quarter length trousers. The man has short, combed-back blonde hair. The woman has short, centrally parted dark hair. She also wears a monocle and is smoking a cigarette. To the right of the man is a large stork, who is biting his raised ankle, to which he responds with some shock. The caption below the picture, at the bottom of the cover, reads ‘Frühling 1926: Selbst der Storch irrt sich!’, which means, ‘Spring 1926: Even the stork is confused!’. This refers to the fact that in German folklore, a pregnant women is said to have been bitten by a stork. In this case, man and woman look so similar that the stork accidentally bites the wrong person.

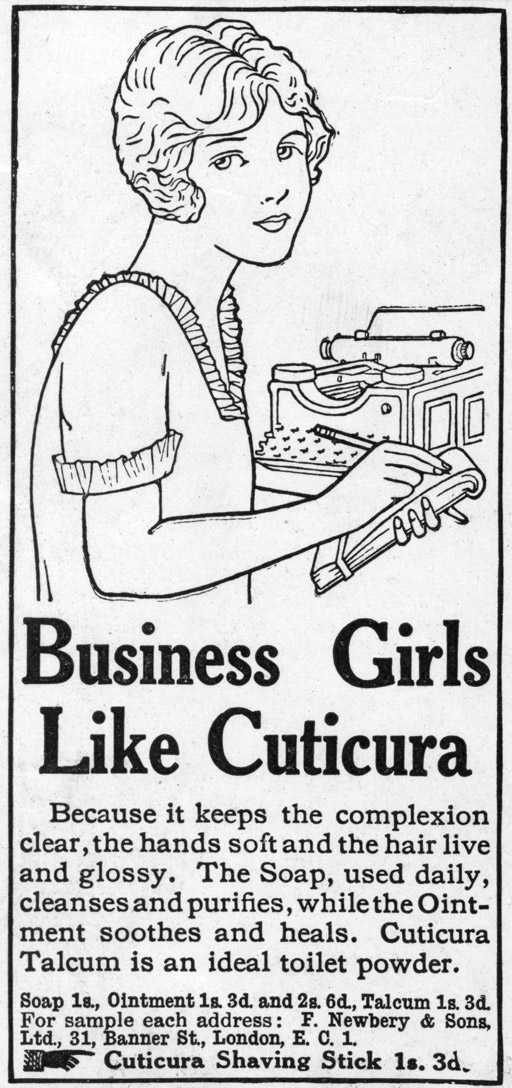

This black-and-white advertisement from the Illustrated London News shows a young woman with short hair, wearing a short-sleeved top with a ruffled v-shaped neckline, holding a pencil and notepad with her neatly manicured hands. She gazes sweetly at the reader. Behind her and slightly to her right is a typewriter which, together with her notepad, suggests that she is an administrative assistant. The caption for the advertisement reads ‘Business girls like Cuticura’, and a short blurb below explains the beauty products being advertised – soap, ointment and talcum powder – together with the current retail prices.

Activity 10

Look at the two images of women in Figures 2 and 3 and answer the following questions:

- The two images are different types of primary source – can you identify these?

- In what light is women’s fashion presented in both of these images? Can you spot the similarities and/or differences in the portrayal of women’s fashion?

Specimen answer

- Both of these images appear in contemporary newspapers. However, the first image is a satirical cartoon published in a German weekly periodical, ULK (which means ‘joke’ or ‘fun’ in German) and the second image is an advertisement published in the Illustrated London News, a weekly British newspaper. The images probably have different audiences, the first intended to amuse (at least predominantly) male readers and the second aimed at female consumers.

- Both images contain a representation of the ‘New Woman’ – that is, an (at least superficially) independent woman clothed in the new rational fashions. However, there are some important differences. In Figure 2, women’s fashion is presented in a negative light. The implication is that women’s fashion has become so masculinised that even the stork cannot tell who is the man and who is the woman. (In German folklore, if a stork bites a woman she will have a baby – in the cartoon, the stork has bitten the man by accident.) In Figure 3, fashion is presented in a positive light. The woman is wearing the current fashion and purchasing new beauty products, but here that serves to enhance her femininity, despite the fact that she is outside the domestic sphere (and the test of the advertisement implies that these products help this woman to do her job).

Discussion

These images capture the two competing narratives encapsulated in the image of the ‘New Woman’: that of ‘archetype’ and that of ‘consumer’ (Saunders, 2005). On the one hand, the archetypal ‘New Woman’ – employed (and hence independent), single and in pursuit of pleasure – was viewed by many contemporaries, especially at a time of declining birth rates, with scorn. Her modern or masculinised clothes were symbolic of the challenge she presented to traditional male roles and authority, fuelling a crisis of masculinity. As Mary Louise Roberts has written: ‘The blurring of the boundaries between “male” and “female” – a civilisation without sexes – served as a primary referent for the ruin of civilization itself’ (1994, p. 4). In Source 4, Bingham mentions several historians (in particular Beddoe and Melman) who have emphasised the role played by the interwar press in Britain in the ‘backlash’ against perceived new freedoms for women, presenting hostile images of the ‘New Woman’ while reasserting the role of women in the domestic sphere through advertising and special features.

On the other hand, the ‘New Woman’, with her disposable income, was also seen as a consumer. This happened to coincide with the expansion of the mass media. Hence new fashions and beauty products were promoted by newspapers, sometimes in advertisements boasting domestic scenes and sometimes in advertisements displaying women in the public sphere. Crucially, the vast majority emphasised the femininity of women and the importance of beauty products in enhancing female elegance, while offering little challenge to male authority (you might note that the woman in Figure 3, sitting by the typewriter, is employed in a secretarial role and hardly a challenge for the male executives she works for). At the same time, though, you should note the aspirational value of the advertisement.

Few would deny that women’s fashion changed dramatically at the end of the First World War: skirts were shortened (to above the knee, for the first time in history, by 1924) and rigidly shaped garments replaced with looser-fitting clothes, hair was shaped into bob styles, and cosmetics and other beauty products were both widely accepted and used to enhance features. As Mila Ganeva has written, ‘it was during the 1920s that women began … to dress in a way that we can identify with today’ (Ganeva, 2008, p. 3). Historians such as Martin Pugh have argued that these changes were rooted in wartime experiences: in Britain at least, as a sign of patriotism, women shortened their skirts to economise on material (Pugh, 2009, p. 171). However, others have pointed to the influence of trends in the major Parisian fashion houses on the eve of war (McElligott, 2001, p. 201; Søland, 2000, pp. 22–3), as well as state- and market-driven changes in clothes production that favoured mass-produced ready-to-wear garments over traditional artisanal creations (De Grazia, 1992, p. 221). I could also point to the impact of new employment opportunities for women in the white-collar sector as clerks and sales assistants, which sparked demand for more rational and functional clothes.

Whereas previously the affluent would have ordered clothes from a fashion house, while those at the lower end of the social hierarchy would have relied on a few garments sewn by local artisans or themselves and often passed between family members, the new simple styles allowed for the tremendous expansion of the ready-to-wear market across Europe. By the mid-1920s, Konfektion (ready-to-wear) had become an essential branch of the German economy, and by 1927 there were 800 firms located in Berlin alone employing more than one-third of the city’s workforce (Ganeva, 2008, p. 4). The industry increased the choice that was available to women seeking employment. Elizabeth Bright Jones has shown how female agricultural workers in rural Saxony actively sought alternative employment in these and other factories, and a range of surveys of German schoolgirls highlighted changing aspirations for future employment, some of which had been initiated by changes in the fashion industry (Jones, 2001; McElligott, 2001, pp. 198–200). Moreover, at least a portion of the wages that these young single women earned fed back into supporting the fashion industry, as they became important consumers not just of ready-to-wear but also of cheap cosmetics (Todd, 2005, p. 803).

Even if the common image projected across Europe was one of the urbane, fashionable New Woman, the reach of fashion, and its potential to generate change, stretched much further than this. A number of historians have pointed to the democratisation of fashion during the 1920s. The latest trends thought up in the haute couture fashion houses of Paris were now rapidly copied by the ready-to-wear factories and put on sale in the department stores for the middle classes. Moreover, those working women who could not afford the rack prices were able to sew their own as a result of a booming pattern market and the availability of cheap fabrics (Stewart, 2008). Ease of copying also helped to break down traditional urban–rural divides. Victoria De Grazia has suggested that the village girls in Italy ‘wore the same bright colors, “autarchic” silks, hiked-up skirts, and shorter hairstyles as urban working girls’ (De Grazia, 1992, p. 221). Age, however, continued at least in some areas to be an important differential, as some women of the older generations refused to adopt the new styles (Søland, 2000, p. 1). Figure 1 also suggests that peasant women of central Europe found new fashions inaccessible or impractical.

The introduction of new fashions for women was not always a smooth process. Roberts has described in detail the tensions and rifts that erupted in French families: ‘Throughout the [1920s], newspapers recorded lurid tales, including one husband in the provinces who sequestered his wife for bobbing her hair and another father who reportedly killed his daughter for the same reason’ (Roberts, 1993, pp. 657–8). You have already examined a negative portrayal of masculine fashions that appeared in print culture. However, these must be balanced against evidence that changing fashions were fairly rapidly accepted. Contemporary surveys of German men suggest that many were finding it easier to accept changes in the appearance of women than is sometimes believed (McElligott, 2001, p. 205). Finally, new fashions were central to the sense of modernity that characterised the identity of the postwar generation. Evidence from autobiographies and oral history interviews has led Birgitte Søland to argue that young Danish women used new fashions to set themselves apart from older generations. One interviewee, Charlotte Hensen, explained that: ‘Our generation was different. We were not content to just sit still and do nothing. Corsets and stays, that was not for us. We did not want to wear all those heavy clothes. They just did not fit us’ (Søland, 2000, p. 41). Yet, even if new garments, hairstyles and cosmetics made young women feel modern, they did not necessarily offer liberation, nor was it sought. New fashions demanded as much time and upkeep as previous fashions, and the majority of young women, even those fortunate enough to have some disposable income from their employment, continued to marry and enter the domestic sphere.

6 Governments and populations

Deborah Brunton

Another of the key features of modernisation in twentieth-century Europe was the changing relationship between ordinary people and the state. In the nineteenth century, the state would have impinged very little on the lives of peasant farmers or industrial workers; in the early twentieth century, local and central governments increasingly regulated their behaviour and supported them through periods of crisis. State support for the sick, the old and the young began in the 1880s in Germany, when the first old-age pensions and sickness and unemployment insurance were established. Other countries followed suit. For example, Britain introduced state pensions in 1908 and a range of benefits under the 1911 National Insurance Act, and Sweden introduced pensions in 1913. In addition, governments began to offer a range of health and welfare services.

Historians have traditionally seen the state provision of health services as a rational response to disease, initiated and shaped by medical experts and bureaucrats. However, more recently, many historians of public policy and medicine have argued that health services were fundamentally shaped by broader social, political and moral ideas. Policy was driven not only by central government but also by charities, political groups, dedicated campaigning associations and local government, many of whom were active in providing services. Putting policy into practice involved a range of experts – doctors, nurses and health visitors. As a result, welfare policies varied from country to country, reflecting particular social and political contexts.

Behind the drive to introduce new forms of welfare and of health provision in the early twentieth century was a concern about the strength of populations. As you have seen, the growth rate of populations was slowing before the First World War and remained low after 1918. In the 1930s, statisticians produced alarming projections of the size of national populations: the population of Britain would be just 28 million by 1976 and 17 million by the year 2000 (Glass, 1967, p. 84). The population of France was predicted to fall from 41 million in 1931 to 29 million in 1980. Towns would be deserted, and factories would lie idle for lack of workers. As well as worrying about the size of the populations, commentators were also concerned about the health and strength of individuals. Wartime recruitment had shown that many of the poorer classes were small or weak, or had defective teeth or eyesight. The size of population and the fitness of its men mattered: at a time of intense national rivalries, ‘population was power’ (Davin, 1978, p. 10). A small, weak population could not provide workers to support industries or manpower to supply the armed forces. As one British MP remarked: ‘The empire cannot be built on rickety or flat-chested citizens’ (Davin, 1978, p. 17). All over Europe, governments made unfavourable comparisons between their own populations and those of their competitor states. Medicine offered possible solutions: encouraging healthy parents to have more children, ensuring that infants received a good start in life and controlling diseases that weakened the adult population.

Infant welfare