The Enlightenment

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 18 April 2024, 9:08 AM

The Enlightenment

Introduction

The course will examine the Enlightenment. To help understand the nature and scale of the cultural changes of the time, we offer a 'map' of the conceptual territory and the intellectual and cultural climate. We will examine the impact of Enlightenment on a variety of areas including science, religion, the classics, art and nature. Finally, we will examine the forces of change which led from Enlightenment to Romanticism.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 2 study in Arts and Humanities.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand the cultural climate that existed as the Enlightenment began

understand the main characteristics of the Enlightenment

demonstrate an awareness of the cultural shifts and trends leading from Enlightenment to Romanticism.

1 'The Enlightenment'

What a change there was between 1785 and 1824! There has probably never been such an abrupt revolution in habits, ideas and beliefs in the two thousand years since we have known the history of the world.

(Stendhal, Racine and Shakespeare, 1825; 1962 edn, p. 144)

This course looks at a period of 50 years or so during which European culture underwent one of the most profound and far-reaching changes in its history. This occurred against a background of political and social turmoil and transformation equally unprecedented, marked by revolution, war and the beginnings of industrialisation. The period saw the interface of two fundamental cultural movements: Enlightenment and Romanticism. The transition from the first to the second has been described as ‘the greatest single shift in the consciousness of the West that has occurred’ (Berlin, 1999, p. 1), one that ‘cracked the backbone of European thought’ (Isaiah Berlin, quoted in Furst, 1979, p. 27), and it continues to impact on our ways of thinking in the twenty-first century.

In order to help you get to grips with the nature and scale of the cultural changes that took place, we intend to offer a ‘map’ of the conceptual territory, the intellectual and cultural climate. As we proceed, we shall point to some of the key texts of the period, but we shall continue to concentrate largely on the Enlightenment, drawing your attention to the major figures and works characteristic of this movement. We shall ask you to watch video clips in which some important aspects of the Enlightenment are discussed further, and to attempt the corresponding exercises set in the Audio-Visual Notes. We shall also outline briefly some of the main changes that began from about 1780, principally with regard to the shift towards Romanticism.

As you work through this course please bear in mind the learning objectives specified above. At this stage you are asked simply (1) to gain a basic understanding of the cultural climate that existed as the historical period we shall be studying began; (2) to grasp the main characteristics of the Enlightenment; and (3) to be aware of some of the cultural developments leading from Enlightenment to Romanticism. You will encounter in this course a great deal of supporting detail that you will not be expected to memorise.

In order to help you to work smoothly through the course, we have highlighted in bold the summary points that we expect you to absorb. We have also highlighted in bold at their first mention the names of the institutions, historical phenomena and authors of texts that featured prominently at that time.

2 The Enlightenment and its mission

2.1 Definitions

‘The Enlightenment’ is used to refer:

to a chronological period (roughly, the middle and late decades of the eighteenth century between around 1740 and 1780), often also called ‘The Age of Reason’; and

to the unprecedented focus on a particular set of values, attitudes and beliefs shared by prominent writers, artists and thinkers of that period.

There were changes of emphasis depending on date: it is common to distinguish, for example, between early and late Enlightenment attitudes, while the half-century beginning around 1680 is often thought of as the pre-Enlightenment. There were also different ‘varieties’ of Enlightenment depending on national, social and political contexts. The sweep of the Enlightenment was enormous: from Lisbon to Saint Petersburg and from Edinburgh to Naples. Enlightenment culture spread from one nation to another, defining a pan-European consciousness of tremendous force. Each nation added its own dimension. In France, for example, there was a much greater sense of opposition to the (Catholic) Church than in England, where the religious establishment was perceived to be far less oppressive. It is agreed that the Enlightenment was at the height of its influence in the 1760s and early 1770s. Of its most representative figures in France, Voltaire died in 1778 and Diderot in 1784 (see Figures 1 and 2). There is also a consensus that certain key attitudes characterise what we may describe as an Enlightenment outlook.

The Enlightenment consisted, in essence, of the belief that the expansion of knowledge, the application of reason, and dedication to scientific method would result in the greater progress and happiness of humankind. The Enlightenment outlook was buoyant, reformist and humanitarian. The archetypal Enlightenment thinker was confident that the world is ultimately both rational and beneficent, that nature, including humanity, is essentially good or at least not innately depraved, and that people have the potential to improve themselves and their environment and to make the world a better place.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Among the factors that gave particular credibility to this belief one ranks high: the epoch-making discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727) at the end of the seventeenth century regarding the motion of the planets and gravitational force. Newton's achievements had a profound and lasting impact that spread far beyond the sphere of physics. They suggested that the natural world could be explored and understood, and that nature and everything in it was governed by underlying ‘laws’; that there were rational, universally valid answers to the questions asked by an enquiring mind; that for every effect there was an identifiable cause, for every natural phenomenon an explanation, a category and a definition, if only we try hard enough to find it. This confidence in reason or intellect lies at the heart of the Enlightenment.

2.2 The Encyclopédie

The text that best exemplifies and embodies this outlook is the French Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonne des sciences, des arts et des metiers (Encyclopédia, or an Analytical Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts and Trades), published in Paris between 1751 and 1772 in 28 volumes and accompanied by 11 volumes of illustrative plates. (Further supplementary volumes were published almost up to the French Revolution in 1789.) The main editor of the work was Denis Diderot (1713–84, pronounced Dee-der-oh), assisted in the early stages by Jean d'Alembert (1717–83). The Encyclopédie certainly took seriously its remit of collating and communicating all available knowledge in the interests of progress. The following statement from one of Diderot's many articles in the Encyclopédie, the one entitled ‘Encyclopaedia’, sets out the basic manifesto of the Enlightenment:

The aim of an Encyclopédia is to bring together the knowledge scattered over the surface of the earth, to present its overall structure to our contemporaries and to hand it on to those who will come after us, so that our children, by becoming more knowledgeable, will become more virtuous and happier; and so that we shall not die without earning the gratitude of the human race.

(Diderot, 1755, p. 635; trans. S. Clennell)

In that one brief statement we find the essence of the Enlightenment credo: that increase of knowledge will produce happier, more virtuous people. The message is one of universal application, appropriate to the entire human race. It was self-evidently better to be right than to be wrong: that is, to have a correct understanding of things, the relationship between them, and the ‘laws’ that governed those relationships. To be informed was manifestly better, more virtuous, than to be ignorant or prejudiced. Hence, as Diderot continued, all knowledge was good in itself; the discovery of truth in any field of human activity was a contribution to the advancement of human knowledge, and therefore to the advantage and ultimate happiness of humanity; the Encyclopédie, whose purpose was to spread that knowledge, was a worthy instrument of the Enlightenment. ‘Enlightenment’ itself (and its variants in other languages) signified the emergence of light and the dispersion of the clouds, particularly the clouds of ignorance, superstition, prejudice, oppression, dogma or myth. As Diderot insists later in the same article:

All things must be examined, debated, investigated, without exception and without regard for anyone's feelings … We must ride roughshod over all these ancient puerilities, overturn the barriers that reason never erected.

(Gendzier, 1967, p. 93)

Many of the authors who contributed to the work – the encyclopedists – were known as philosophes. These were not philosophers in our modern sense of the word, but a loose-knit group of like-minded intellectuals and cultivated, sociable and lively writers. Sharing a common view of the Encyclopédie and its mission, they were immensely knowledgeable in an age when it was still possible to have a good grasp of most branches of learning. Of all the encyclopedists, it was perhaps Francois Arouet de Voltaire (1694–1778) who best personified the French Enlightenment: not only in his enormous and varied literary oeuvre, ranging from neoclassical tragedy to modern history and from Newtonian science to literary criticism, but also in his passionate, energetic, highly charged and publicised commitment to Enlightenment values, a commitment which seemed to intensify as he grew older. As ‘the patriarch of Ferney’ in the 1760s and 1770s, he settled in semi-exile at Ferney, near the Swiss border; he also kept a house in Geneva as a bolt-hole in case of trouble from the French authorities. Voltaire was known throughout Europe for his active intervention in humanitarian causes and his incessant attacks on abuses of every kind, particularly abuse of power by the Catholic Church and associated miscarriages of justice. All this was given sensational coverage by his flair for publicity, his Europe-wide contacts among influential people, including crowned heads – notably Frederick the Great of Prussia and Empress Catherine the Great of Russia – and above all by his inimitable style, pointedly ironic, forceful, mischievous, malicious and funny. Voltaire never missed his target. He made the authorities, the ecclesiastical perpetrators of superstition and cruelty, smart. He made them look not merely wrongheaded, wicked and unjust, but more – he made them look ridiculous. Voltaire's style also reflects another Enlightenment characteristic: its even, moderate temper, urbane, measured and witty. Passionately as Voltaire felt about fanaticism, cruelty and injustice, his strength of feeling was the more effective for its control, the rippling, amusing surface elegance beneath which a biting wit and irony fizzed, flashed and exploded. Voltaire's best-known work, which best reflects his character and style, is his ‘philosophical tale’ Candide (1759). Here, for example, is a statement by one of its main characters, a part-Spanish valet Cacambo, about the colonial impact of the Jesuit Fathers in Paraguay (the Jesuits were a body of Catholic missionaries):

I know how the reverend fathers govern as well as I know the streets of Cadiz. It's a wonderful thing, their system of government. The kingdom is more than three hundred leagues across; it is divided into thirty provinces. The reverend fathers own everything, and the natives nothing. It is a masterpiece of reason and justice.

(Voltaire, 1981, p. 88; trans. Lentin)

This French Enlightenment tone and temper – detached, ironic and at times wickedly or darkly humorous – should be remembered when we come to discuss the very different Romantic temperament.

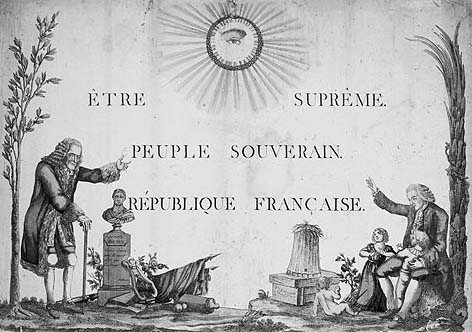

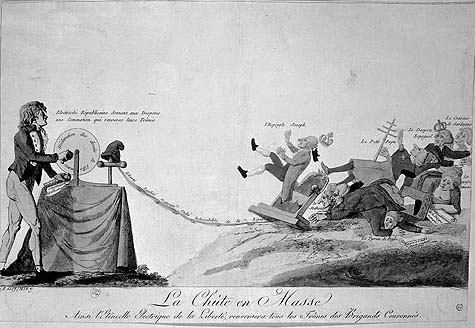

Although the term philosophe was French and applied mainly to thinkers from that country, it was also applied to intellectuals of any country who were sympathetic to an Enlightenment approach. Of the encyclopedists themselves, Baron d'Holbach (Paul Henri Dietrich) was a German expatriate and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–78) was Swiss. ‘My dear Davy,’ Diderot wrote to the Scots philosopher David Hume (1711–76), ‘you belong to all nations … I flatter myself that I am, like you, [a] citizen of the great city of the world’ (quoted in Gay, 1968, p.13). Diderot spoke for the thoroughly cosmopolitan spirit of the Enlightenment. French was the common language of the Enlightenment, as the Berlin Academy of Arts and Sciences acknowledged in 1783 when it set an essay competition on ‘the universality of the French language’. The publications of the French philosophes were followed by an eager, albeit elite, readership across Europe. ‘I see with pleasure’, Voltaire wrote to a Russian in 1767, ‘that an immense republic of cultivated minds is being formed in Europe’ (quoted in Sorel, 1912, p. 166; trans. Lentin). There were varieties of the Enlightenment in Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria and Russia; there was a distinct and distinguished Scottish Enlightenment (of which Hume was a leading figure), and in England there were even a Midlands Enlightenment and a Manchester Enlightenment. But it was in France that the rational, reformist agenda of the Enlightenment found its most forceful expression (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

The philosophes saw themselves as engaged in a battle for minds; they appealed to something which they saw and cultivated as a new factor in European society: public opinion. It was with public opinion in mind that they criticised existing institutions in France and what they saw as a corrupt and ineffective absolute monarchy in alliance with a corrupt and repressive Catholic Church. While they had friends in high places who assisted the project, the Encydopédie had a stormy publication history, since its content and tone went far beyond the conventional remit of summarising and categorising knowledge. Its social and political polemic often operated through a subversive system of cross-referencing and ironic word play in an attempt to circumvent strict censorship laws, but this did not prevent several serious delays to publication of the work and determined opposition from powerful quarters.

Exercise 1

So far in this section you have been introduced to the main mission of the Enlightenment. Try now to stand back from the detail of the section, and summarise in about 50 words what you see as the main characteristics of that mission.

Discussion

The main characteristics of the Enlightenment's mission were:

- a confidence in reason or intellectual enquiry to bring greater happiness and progress to humanity;

- a belief that all aspects of the human and natural worlds are susceptible of rational explanation; and

- the desire to battle against ignorance, dogma, superstition, injustice and oppression.

How did you fare in this exercise? Did you write much more than the summary discussion set out in the discussion above? If so, it may be that you need further practice in the skill of extracting key points and summing them up concisely. You have encountered so far in this section a general exposition of the main characteristics of the Enlightenment mission, followed by some more detailed discussion of historical examples: the Encydopédie and the writings of Voltaire. This combination of main points interwoven with or succeeded by illustrative detail is commonplace in academic writing. Detail has a useful function and is essential in academic study. It both illustrates and validates general claims. But its overuse can bring the risk of obscuring the main points of an analysis: ‘not seeing the wood for the trees’. The required balance between analysis (the ordering and identification of a number of interrelated points relevant to a set question) and illustrative detail or textual evidence will vary.

Try to keep in your mind this distinction between detail and argument as you read the rest of this course. Often the main point being made will be highlighted in some way – perhaps by being stated at the opening of the section or at the beginning or climax of a paragraph, although some paragraphs (such as the paragraph above on Voltaire) will be devoted almost exclusively to the exploration or discussion of particular cases. Try to read the course so that you track the main points carefully and read through the examples more quickly. In order to help you develop this skill of prioritising your attention as you read, we have highlighted summary points in bold in each section of this course. We have also followed a procedure of including in each section the following elements, which appear in different combinations, proportions and sequences:

- a brief statement on one or more main points relating to the Enlightenment;

- some specific historical examples (including some on the introductory video); and

- some indication of the ways in which the main texts of period are located in the general ‘landscape’ of the Enlightenment.

Exercise 2

Open the Audio-Visual (AV) Notes by clicking on the 'View document' link below. After you have viewed the video (‘The Encyclopédie) and attempted the exercise relating to it in the notes, return to this course.

Video 1 'The Encyclopédie' Click within the blank screen to play video

Transcript: The Encyclopédie

Click on 'The Encyclope´die' to read the notes and exercise for video 1

Discussion

Summary point: the main mission of the Enlightenment was to increase human happiness and progress by the application of reason. Enlightenment thinkers used reason or intellect to fight against dogma, superstition, injustice, prejudice and oppression. They saw all areas of human enquiry as susceptible to reasoned understanding of cause and effect, ultimately expressible in terms of universal laws or principles.

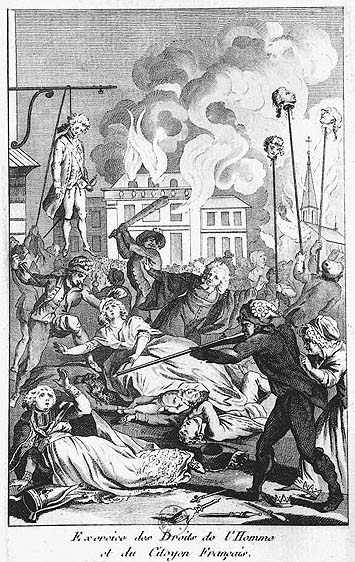

2.3 The pervasive influence of Enlightenment

You will find in this course in one form or another the pervasive influence of the Enlightenment. Sometimes this influence is buried in deeply ambiguous texts such as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's (1756–91) opera Don Giovanni (1787), which includes a famous toast to ‘liberty’. The opera is seen by some as an attempt to subject to critical scrutiny the behaviour of at least one member of a corrupt eighteenth-century aristocracy and the social or class structure that facilitated his egoism. The French Revolution also unleashed a tremendous blast of energy which inspired its leaders with a sense of missionary zeal. Those involved in the Revolution believed, initially at least, that the Enlightenment had pointed the way towards political reform and the kind of system in which its principles could be put into practice. Many across Europe shared this enthusiastic belief. The German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) hailed the opening stages of the Revolution as ‘the enthronement of reason in public affairs’ (quoted in Barzun, 2000, p. 430).

Many aspects of Napoleon's (1769–1821) regime – and certainly the image he sought to project of it – exemplify the intellectual and moral appeal of the Enlightenment. During the Revolution and on an even greater scale under Napoleon, the French not only prided themselves on being what they called la grande nation (the great nation) but also spilled across their frontiers and expanded France by force of arms. In the process they introduced across most of Europe systems of rational administration and modern laws and institutions owing much to the Enlightenment. The French saw themselves as bringing freedom, light, reason and modernity to Europe, and it is significant that their belief was long shared by many who came under French rule. This was perhaps an intense magnification of the general self-perception of enlightened Europe as a whole as the cultural centre of the world. Not that Europe was inward-looking: when Napoleon was sent to conquer Egypt from the Turks in 1798, he took with him 167 scholars, scientists, archaeologists and artists to map, survey, explore and describe the country; to investigate the antiquities of the land of the Pharaohs; and to publish their findings in 20 massive volumes. They were as fascinated by the civilisation of ancient Egypt as they were contemptuous of the backwardness of modern Egypt, and Napoleon briefly ruled the country with a rod of iron. The whole enterprise was an example of ‘the Enlightenment in action’ (Barzun, 2000, p. 445). Of course, this willingness to look beyond Europe was often motivated by commercial colonial interest. The East India Company, founded in London in 1600 and extremely active in the eighteenth century, was a classic example of a commercial enterprise established by the British to maximise profits.

The Enlightenment mission is evident in Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa (1799) by the Scot Mungo Park (1771–c.1805); the author, sponsored by the African Association on a voyage of exploration, built on the tradition of the knowledge-extending expeditions to the Pacific of Captain Cook. He wrote about his travels in order to increase his readers’ knowledge of African geography and societies. To stereotypical European perceptions of Africans as ‘barbaric’, Park brought corrective insights based on his own first-hand observation and experience. This was one of many examples of reason correcting prejudice. Even as Romanticism was gaining pace in literature and art, the Enlightenment's concern for accurate facts and sound reasoning persisted in many areas of intellectual enquiry. The Evangelical Christian and anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce (1759–1833), in his thoughts on religion and slavery, adopted the archetypal Enlightenment procedure of structured, rational ‘enquiry’, seeking out the relationship of cause and effect in society's responses to these burning issues. Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil of Slavery (1787) by Quobna Ottobah Cugoano (1757–c.1800) followed the Encyclopédie in applying rational, critical understanding to the practice of slavery in order to support the abolitionist cause, while other Enlightenment thinkers were using reasoned argument to support its retention.

Robert Owen (1771–1858) applied the critical reformist spirit of the Enlightenment in A New View of Society (1813–16), in which he set out his views on the management of industry and its workers based on his experience at the mill in New Lanark. He shared the Enlightenment's faith in the improvement, through the application of reasoned principle, of the individual and of society at large, and he used these beliefs to shape the work and the domestic environment of the mill-workers. Among the progressive Enlightenment thinkers of Manchester who debated topics as diverse as population growth, poverty, health, education, commerce and philosophy, Owen had gained knowledge which he saw as ‘useful’ in educating and reforming the character of these workers, thus ensuring their productivity and, he believed, their happiness. For Owen, as for most Enlightenment thinkers, the creation of happiness was a rational business, with identifiable causes and effects that could be formulated as universally applicable principles. The world did not have to be a vale of tears or a preparation for other states of existence. The very object of government, indeed, was held to be the maximisation of pleasure, the greatest happiness of the greatest number, or – in the words of the Declaration of Independence with which the American revolutionaries set Europe the example of deliberate, purposeful, rational political change – ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’. Owen identified himself explicitly with the Enlightenment cause by taking a stance against the ‘ignorance and consequent prejudices that have accumulated through all preceding ages’ (Owen, 1991, p. 70), and was representative of that branch of the Enlightenment concerned with practical reform.

The application of reason and knowledge to practical reform was also the concern of the British Royal Institution, founded in 1799, which promoted the study and popularisation of science in the interests of practical improvements in, for example, agriculture, industries such as leather tanning, and, more broadly, the condition of the poor and the prosperity of society in general. The scientist Humphry Davy (1778–1829) expressed his commitment to the discovery of universal principles or laws in chemistry. Napoleon drew up his Civil Code and introduced it across much of Europe, inspired by the Enlightenment idea of laws and principles of universal application. Beneath all of these spheres of enquiry covered in the course, there lay a terrific confidence in all-embracing explanations.

This desire to extend and increase knowledge was evident in concerns of a less overtly practical nature. Edmund Burke (1729–97), in his A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful (1757), set out to define, categorise and explain the nature and causes of the responses to art experienced and discussed by his contemporaries. Burke sought, in relation to aesthetics, to identify the properties of ‘the beautiful’, to distinguish the merely beautiful from ‘the sublime’, and to pinpoint their effects on the beholder. Sir John Soane's (1753–1837) museum, given to the nation in 1833, can also be seen as an example of this classificatory and educational impulse, this time in relation to physical artefacts. This desire to classify, demystify and explain aesthetic experience had a profound effect on theorists, writers and painters, who felt that art itself was susceptible of rational explanation and control. In every art, craft and field of learning, knowledge was power and the key to progress. The Enlightenment mission penetrated all aspects of human thought and activity.

3 Enlightenment, science and empiricism

The Enlightenment's dedication to reason and knowledge did not come out of the blue. After all, scholars had for centuries been adding to humanity's stock of knowledge. The new emphasis, however, was on empirical knowledge: that is, knowledge or opinion grounded in experience. This experience might include scientific experiments or firsthand observation or experience of people, behaviour, politics, society or anything else touching the natural and the human. For any proposition to be accepted as true, it must be verifiable, capable of practical demonstration. If it was not so verifiable, then it was an error, a fable, an outright lie or simply a hypothesis. Although Enlightenment thinkers retained a role for theoretical or speculative thought (in mathematics, for example, or in the formulation of scientific hypotheses), they took their lead from seventeenth-century thinkers and scientists, notably Francis Bacon (1561–1626), Sir Isaac Newton and John Locke (1632–1704), in prioritising claims about the truth that were backed by demonstration and evidence. In his ‘Preliminary discourse’ to the Encyclopédie, d'Alembert hailed Bacon, Newton and Locke as the forefathers and guiding spirits of empiricism and the scientific method. To any claim, proposition or theory unsubstantiated by evidence, the automatic Enlightenment response was: ‘Prove it!’ That is, provide the evidence, show that what you allege is true, or otherwise suspend judgement.

It would be difficult to exaggerate the prestige which Newton's discoveries gave to the method whereby he arrived at them. Empiricism worked and was seen to work. It was verifiable; the experiments could be repeated time and again, always with the same result and revealing the same connection between cause and effect, the same immutable underlying ‘laws’ of nature in operation. In the well-known epigram of Alexander Pope, Newton's elevated status is clear:

Nature, and Nature's Laws lay hid in Night,

God said, Let Newton be! and All was Light.

Both the philosophical and practical advantages of Newtonianism and the scientific method were further and vividly brought out in the second half of the eighteenth century with startling advances in industrial technology. The Encyclopédie was explicitly inclusive of ‘the arts’, and in the eighteenth century these included technology and the mechanical arts. In his article ‘Stocking-machine’ in the Encyclopédie, lavishly illustrated in one of the supplements, Diderot showed how mechanisation ingeniously multiplied human efforts and thus facilitated human comfort and convenience. In Britain, improving on James Hargreaves's spinning-jenny (1764), Richard Arkwright with his water-frame (1768) and Samuel Crompton with his mule (1779) applied technology to the mass production of cloth by steam-driven machines. Such labour-saving devices, so manifestly advantageous, illustrated the triumph of scientific method and Enlightenment rationalism. Empiricism was thus central to the Enlightenment's desire to establish knowledge on firm foundations rather than blindly following authority, convention, tradition and prejudice. Where such foundations were lacking, where the speaker or writer could not satisfactorily respond to the challenge to ‘prove it’, it was clear that their claims should be met with a strong measure of scepticism.

Exercise 3

Try to formulate in roughly one sentence the summary point for the argument starting with the subheading ‘Enlightenment, science and empiricism’.

Discussion

Summary point: Enlightenment thinkers placed particular emphasis on empirical knowledge and what they described as scientific method: that is, knowledge verifiable by reference to experiment, experience or first-hand observation.

Empiricism was applied to every aspect of human thought and activity. The Scottish philosopher David Hume's approach to the issues of suicide and the immortality of the soul is suffused by a respect for the demands of empirical reasoning and the related question, ‘Is such-and-such a factual claim probable in the light of common human experience?’ Hume dismissed with evident relish all speculative reasoning not based on verifiable fact. By speculative reasoning he meant, above all, that based on religious revelation, private intuition, theological dogma and the authority of the churches. The explorer Mungo Park and his close associate, the scientist and botanist Joseph Banks (1743–1820), shared this concern with close observation as the basis of our knowledge of the world, though Park was a believing and practising Christian. The scientific method was happily applied in the eighteenth century by many believers and men of the cloth, who, unlike Hume, felt that science reinforced rather than undermined the reasonableness of religious belief. Cugoano's arguments against slavery were also based on appeals to observation and experience, inviting the reader to judge for himself. Landscape artists and theorists both amateur and professional, such as William Gilpin (1724–1804) and John Constable (1776–1837), paid greater attention to direct observation and sketching of their subject rather than simply the careful imitation of revered masterpieces of the past. This practice was not an eighteenth-century invention, but firsthand studies of the landscape assumed greater importance in relation to studio work as the century progressed. Seeing and thinking for yourself and drawing on the evidence of the five senses were central to the Enlightenment mindset.

Specialisation of knowledge was less common in the eighteenth century than it is today, and the boundaries of what we now call ‘science’ were defined relatively late in the nineteenth century. For the philosophes and Enlightenment men and women generally, an interest in botany or chemistry might sit happily alongside intellectual enquiry into politics, art, literature and economics. As well as being an explorer, Mungo Park, who had qualified as a surgeon, had a keen interest in natural history and in the system of the Swedish naturalist Carl von Linnaeus (1707–78) for the classification of plants. It was common to speculate on connections between science and other subjects such as human nature, religion and morality. There were many debates, for example, on the workings of the nervous system in relation to the question of how far we are responsible for our actions, or on the physical laws of the natural world in relation to the nature or indeed the existence of God.

The Royal Institution in London played a large part in making science a fashionable concern of the educated elite. In the Midlands the Unitarian minister, radical thinker, chemist and inventor of soda water Joseph Priestley (1733–1804) conducted experiments that spread knowledge of experimental science throughout society. A supporter of the French Revolution, he saw the potential of science to contribute to political and religious change. The French scientist Antoine Lavoisier (1743–94) set in motion a development known as the ‘chemical revolution’, which changed the way in which chemical elements were classified, as well as recognising the key role of oxygen in chemical processes. Both the French Revolution and Napoleon's regime perpetuated the Enlightenment emphasis on science as a means of acquiring mastery over the natural world: intellectual power was harnessed in the service of the state. By affording access to the general laws governing the physical universe, science was the strong arm, as well as the foundation, of reason. As Romanticism gained ground in the wider culture, science was sometimes perceived as an antidote (or a salutary, sobering, cold shower) to the feverish ravings of feeling or the imagination. To Enlightenment thinkers, science was much more than a set of topics to be studied. It represented the unshakeable triumph of the empirical method, the crucial testing of hypotheses against evidence, that could be applicable to all aspects of human enquiry, including questions of morality and religion.

Exercise 4

Now read the AV Notes (click 'View document' below), focusing on the section on science, which will direct you to watch ‘Advances in medicine’ and attempt the exercise in the notes.

Click on 'View document' to read the AV notes and exercise for video 2 Advances in medicine'

Click on the blank screen below to start playing video 2 'Advances in medicine'

Transcript: Advances in medicine

4 Enlightenment, religion and morality

4.1 Constant human nature

Just as with other natural phenomena, Enlightenment thinkers came to the conclusion as a result of observation that human nature itself was a basic constant. In other words, it possessed common characteristics and was subject to universal, verifiable laws of cause and effect. As Hume put it:

Mankind are so much the same, in all times and places, that history informs us of nothing new or strange in this particular. Its chief use is only to discover the constant and universal principles of human nature …

(Hume, 1975, p. 83)

Hume was not consistent on this point, and his later writings suggest an essential difference between western and ‘other’ varieties of human nature. Nor did he view female nature in the same light as male. It was also widely accepted that human behaviour and the human condition were susceptible to environmental and educational influence. The desire for moral reform was supported by a belief in universally valid moral standards. The philosophes were confident that it was possible to identify virtue and vice, right and wrong, in a way that may seem alien to us today. If it was possible to discover universal laws that governed the physical workings of the universe, the same, they concluded, applied to the world of morality. In his Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals (1751), Hume confidently declared:

The end of all moral speculation is to teach us our duty; and, by proper representations of the deformity of vice and beauty of virtue, beget corresponding habits, and engage us to avoid the one, and embrace the other.

(Hume, n.d., p. 409)

Summary point: Enlightenment thinkers believed that the basic principles underlying human nature were constant; they also believed that the human condition was susceptible of improvement. They felt it possible to formulate clear moral absolutes or universal standards.

This is one of the main sources of distinction between the Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment eras: later thinkers would be less confident about identifying a uniform human nature or clear moral absolutes. Mungo Park followed Hume in demonstrating, on the basis of his own experience as an explorer, that Africans conformed to a universal human nature rather than being fundamentally different from Europeans, as was contended by many of those engaged in the highly lucrative slave trade. Park's exploration of ‘the dark continent’ achieved much in changing attitudes on this subject. In general, there was a pervasive faith in the potential to discover the laws governing human behaviour and morality. It is possible to see the Enlightenment mindset at work even in works such as Mozart's Don Giovanni, which is open to several interpretations. This opera was influenced by a high art tradition of serious opera or opera seria in which characters overcome their flaws and achieve moral greatness. Commonly in tragedy the theme was the triumph of duty over love or passion. The chief character in Don Giovanni (Don Giovanni himself) does not even attempt this exercise, and is finally punished in a way that suggests the existence of moral absolutes. The opera's alternative title is The Rake Punished.

4.2 Materialism

Increasingly, particularly in late Enlightenment texts, this confidence in our ability to discover and apply clear moral distinctions came into conflict with an alternative view of human nature and morality derived from philosophical materialism, which was particularly influential in France. To a materialist everything, from our nervous system and reflex actions to our innermost thoughts and most ‘mystical’ beliefs, was susceptible to examination by the physical sciences; our thoughts and actions were explicable in purely physical terms. If the universe was a kind of great machine in which everything was subject to unalterable laws, might not the same be true of human beings? Building on the foundations laid by ancient philosophers such as the Roman poet Lucretius (c.98–55 BCE) and bolstered by the Enlightenment's commitment to the physical sciences, many eighteenth-century thinkers, including Diderot, pursued the consequences of this philosophy. Materialism was based on the belief that everything we can know or experience has causes and explanations rooted in physical matter. Such ideas were seen as a threat to traditional religion with its belief in an immaterial or non-corporeal, spiritual soul able to survive the body after death, and also to the concept of free will and the capacity to choose between good and evil.

Materialism, then, had disturbing implications for Christianity and for morality conceived of as obedience to a set of divine injunctions. First, it seemed to leave little scope for God, except as a possible prime mover or great architect of the universe who, having set the universe in motion, thereafter sat back without intervening further, leaving it – and humanity – to operate like automata in accordance with the unalterable laws of nature. From this perspective divine providence, after its initial intervention, was redundant. Second, if everything is reducible to physical phenomena and processes, then physical sensations assume great importance in moral matters. Building on the well-established premise that the seeking of pleasure and the avoidance of pain are central to human happiness and well-being, eighteenth-century materialists rejected the fundamental Christian concept of original sin (humankind's innate depravity) and other guilt-inducing moral dictates in order to focus on human sensations and the relationship between physical and moral health. One consequence of this was a new legitimisation of hedonism, or the conscious pursuit of pleasure.

Summary point: in Enlightenment France philosophical materialism, the belief that everything (including the apparently spiritual) can be explained in terms of physical matter and the laws governing it, became increasingly influential. It encouraged in some thinkers a tendency to argue that all moral matters might be reduced to the maximising of physical pleasure.

The Marquis de Sade (1740–1814) twisted such ideas into perversity by rejecting as a moral criterion everything except that which conduces to the gratification of our physical desires and by defining human nature in terms of the ‘natural’ influences of physiology, environment and climate. This is an approach conducive to amoralism rather than to moral guidelines. Sade's Dialogue between a Priest and a Dying Man (1782) dramatises the encounter of such a credo with the priest's conventional but ultimately assailable Catholic beliefs. The dying man's self-seeking hedonism conflicts with the Enlightenment requirement for a clearly defined, socially controlled moral code.

Materialism was one of many threats to the status of religion. Enlightenment thinkers analysed and criticised religious beliefs in the same way as they subjected to rational scrutiny secular topics such as geological or economic theories. By refusing to treat religion as sacrosanct or the source of its own authority, they threw down a challenge to ecclesiastical institutions, especially in France, where there was a strong alliance of church and state, and the former was seen both as a support and as a beneficiary (for example, through tax exemptions) of an inherently despotic system of government. The perceived corruption and grip on privilege of the Catholic Church, as well as its role in state censorship and its overall hostility to Enlightenment ideas, provoked in the French philosophes much anti-religious and anti-clerical criticism as well as the kind of sparkling irony and provocative wit that characterised Voltaire's Candide or his Philosophical Dictionary (1764). In Candide, James Boswell noted, ‘Voltaire, I am afraid, meant only by wanton profaneness to obtain a sportive victory over religion, and to discredit our belief of a superintending Providence’ (Boswell, 1951, p. 210). In 1762 the Archbishop of Paris similarly complained about both the Enlightenment message and its tone:

Disbelief has in our time adopted a light, pleasant, frivolous style, with the aim of diverting the imagination, seducing the mind, and corrupting the heart. It puts on an air of profundity and sublimity and professes to rise to the first principles of knowledge so as to throw off a yoke it considers shameful to mankind and to the Deity itself. Now it declaims with fury against religious zeal yet preaches toleration for all; now it offers a brew of seditious ideas with badinage, of pure moral advice with obscenities, of great truths with great errors, of faith with blasphemy.

(Barzun, 2000, p. 368)

The archbishop was right: the philosophes were implying that while the morality preached by Jesus was unexceptionable, educated people would be better off if they jettisoned the age-old lumber of theology, metaphysics, rituals, priests and monks. One of the alternatives frequently recommended to the enlightened was the natural, universal religion of deism, a pure and rational system of ethics uncluttered by dubious miracles, dubious science and dubious history. The authorities took action. In 1766 two young French nobles were sentenced to death for failing to remove their hats and singing ribald songs in the presence of a religious procession honouring the Virgin Mary. Sentence was confirmed by the Supreme Court in Paris, which noted that irreligion was rife and blamed Voltaire's Philosophical Dictionary. One of the young men escaped, and obtained a commission in the Prussian army through Voltaire's intervention with Frederick the Great. The other, the Chevalier de la Barre, was put to death, his tongue excised and his body burned at the stake together with a copy of the Philosophical Dictionary.

Summary point: the French Enlightenment subjected religion and its institutions to rational, secular analysis and was often disrespectful, sceptical and subversive in its attitude to the Catholic Church.

Even Rousseau, a fervent though unorthodox believer, did not escape censure. Both the Catholic Church in France and the Calvinist Church in Geneva were outraged by his suggestion that people were naturally good and that an emotional communion with nature was as sound a basis for faith as the formal teachings of the Church. Rousseau's Emile (1762), in which he advanced these views in a section called the ‘Profession of faith of a Savoyard vicar’, was formally condemned by the authorities at Geneva and publicly burned together with his political tract Du contrat social (Of the Social Contract, 1762). The Archbishop of Paris, the Sorbonne and the high court in Paris likewise condemned Entile to be burned. Rousseau fled to asylum in Prussian territory.

4.3 Responses to religion

Reasoned responses to religion could take many forms. It was rare for writers to profess outright atheism; even in those cases where we may suspect authors of holding this view, censorship laws made their public expression unlawful. These laws were particularly stringent in France. In many cases reasoned critique was applied to the practices of institutional religion, such as the corruption of the clergy or the rituals of worship, rather than to more fundamental matters of doctrine or faith. Wilberforce, a devout Christian, argued that Sunday might be spent more cheerfully than was customary in England, and Robert Owen's attacks on Scottish sectarianism also included complaints about the dour Calvinist sabbath. It was extremely common for those with specific church allegiances to adopt the rationalising approaches popularised in more secular contexts. Mungo Park's Scottish Nonconformity (Park was a ‘Secessionist’, a sect of Protestant Calvinism) was coloured by the deist argument from design, discussed below. In England the Protestantism of the relatively tolerant Anglican Church accommodated a wide range and variety of approach to matters of belief. In both France and Britain there was a wealth of parsons, priests and lay preachers engaged in studying all the topics of interest to the average philosophe. Gilbert White, a country parson, was a naturalist, author of the still popular Natural History of Selborne (1789). One of the most prominent figures of the British Enlightenment, Samuel Johnson (1709–84), was a devout Anglican. In our period, Christianity itself was often orientated towards Enlightenment and reform (Aston, 1990, pp. 81–99). In 1790, when the fiercely controversial reform of the French Church was introduced in revolutionary France, it had supporters as well as opponents among the clergy.

Natural religion was a form of religious belief founded on the observation of nature rather than on revelation or scriptural authority. Often associated with this approach was deism, a particular religious belief which holds that God designed and created the world, but so effectively that there would be no further need for his intervention. Deist views were expressed by those who questioned conventional Christianity and who believed in a universal rather than a sectarian God. They often used reason and argument together with their observation of nature: the existence of a benevolent, intelligent creator or Supreme Being was inferred from observation of the complex but well-ordered and indeed marvellous universe explored, revealed and explained by Newton. (This was called the ‘argument from design’.) The notion of God as a necessary creator, first cause, supreme architect, or a kind of celestial clockmaker who devised and set the universe in motion, was well expressed by writers such as Voltaire. In 1774, at the age of 80 and moved by the spectacle of a magnificent sunrise, he prostrated himself on the ground, exclaiming: ‘I believe! I believe in you! Powerful God, I believe!’ Clambering to his feet, he added dryly: ‘As for Monsieur the son and Madame his mother, that's a different story’ (quoted in Gay, 1968, p. 122). While philosophers such as David Hume questioned the logic behind such professions of faith, others were keen to embrace a belief in God apparently grounded in empiricism. The Catholic Church in France tended to regard deism as located on the slippery slope leading to atheism, while sections of the Anglican Church tolerated and even encouraged deist sentiments as a support to religion. Many Anglicans cited natural religion or deism alongside arguments drawn from the Bible. Cugoano was among those who adopted this eclectic approach in his views on slavery, and Rousseau saw God in nature as well as in the morality of the Gospels. William Gilpin, English parson and writer of travel guides, likewise saw God's presence in the beauty of the landscape while remaining attached to broad-church Anglicanism.

Summary point: deism, a reasoned form of belief in God based on the methods of natural religion – that is, observation of the natural world – often deployed the argument from design. This was the view that the intelligence and goodness of God, as designer of the world, could be inferred from the workings and beauties of nature. Deist arguments were used by those who embraced more traditional forms of worship, as well as by those who wished to challenge them.

Evangelical Christianity in Britain adopted the Enlightenment's concern with empirical investigation and applied it to its thinking on both the natural world and the Scriptures, albeit within the framework of particular religious beliefs, in order to produce a more reasoned form of worship better adapted to modern times. There were many attempts such as these to challenge forms of belief based on an unthinking acceptance of tradition and authority. The intellectual refinement of faith was prevalent. William Wilberforce, in his A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians (1797), subjected the state of contemporary religion to rational scrutiny and connected the decline of faith with increased industrialisation and mechanisation. His method of analysis drew on an enlightened secular approach in order to signal the need for a more intensely experienced form of faith. His personal commitment to religion continued to embrace a non-demonstrable belief in the afterlife. Enlightened rational scrutiny could assist in religious reform without destroying faith.

Setting aside these various shades of response to religious issues, one of the major developments of the Enlightenment was an increasingly secular approach to morality. It became more common for writers of all types of religious persuasion, as well as sceptics and non-believers, to discuss virtue and vice in terms that had little to do with religion or the spiritual and more to do with notions of individual or social well-being. Sade's sensualism rejected conventional Christian morality and social norms in order to take individual self-interest to excessive lengths.

Summary point: the Enlightenment's spirit of rational enquiry was deployed even by those who adhered to an intense spirituality. However, moral debates were increasingly decoupled from matters of religious belief and doctrine.

5 Enlightenment and the classics

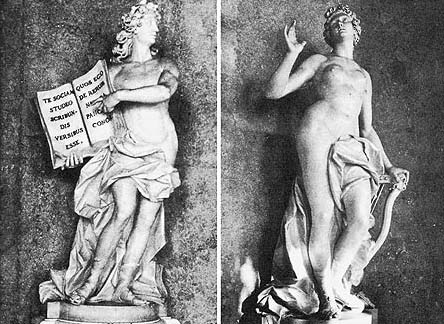

The civilisations of ancient Greece and Rome formed both a common background and a major source of inspiration to Enlightenment thinkers and artists (see Figure 4). The dominant culture of the Enlightenment was rooted in the classics, and its art was consciously imitative and neoclassical. English literature of the first half of the century was known as ‘Augustan’ – that is, comparable to the classic works of the age of the Roman emperor Augustus (27 BCE-CE 14), notably Virgil and Horace and, from the late republican period, Cicero. Augustan literature was characterised by moderation, decorum and a sense of order. The Augustan poet would use classical allusion, authority and satire to convey a deeply reasoned wisdom. The verse of Alexander Pope was quintessentially Augustan in its compressed insights into mankind, expressed in controlled, balanced verse. In his Imitations of Horace, Pope paid tribute to his admired classical model. Horace, he wrote,

Will, like a friend, familiarly convey

The truest notions in the easiest way.

Figure 4

From the grounding in Latin and Greek which formed the basis of their education, the wealthy and well connected of the eighteenth century were at home with the poetry, history and philosophy of the ancient world. In the words of Samuel Johnson, ‘classical quotation is the parole [password] of literary men all over the world’ (Boswell, 1951, vol.2, p. 386). When Johnson dined in company with the disreputable politician John Wilkes, neither thought it out of place to discuss a disputed passage in Horace. James Boswell, Johnson's companion and biographer, and son of a Scottish law lord, the Laird of Auchinleck, recalled how in his youth he had associated well-known passages from classical verse with the natural, indeed ‘romantic’ beauties of the estate:

The family seat was rich in natural romantic beauties of rock, wood, and water; and … in my ‘morn of life’ I had appropriated the finest descriptions in the ancient Classicks, to certain scenes there, which were thus associated in my mind.

(Boswell, 1951, vol.2, p. 131)

Across Europe the social elite studied antique statuary, either by viewing originals or copies close to home or by going on the ‘Grand Tour’ to Italy, to view original sculptures and buildings in Rome itself. To participate in such a tour, to be well versed in the ancient languages and to commission buildings and paintings in the antique style – a portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, a mansion by Robert Adam – signalled membership of a class that felt itself to represent the very best of western civilisation and that surrounded itself with classical statuary or neoclassical artefacts as emblems of wealth, status and power (see Figure 5).

Men and women of the Enlightenment related to, empathised and identified with the ancient world, more particularly with the world of classical Rome, believing that eighteenth-century Europe had achieved a similar peak of cultural excellence. In the words of Edward Gibbon (1737–94 – see Figure 6), author of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–88), contemporary Europe was ‘one great republic, whose various inhabitants have attained almost the same level of politeness and cultivation’ (Gibbon, 1954, p. 107). By contrast, eighteenth-century Europe tended to reject as ‘barbarous’ or ‘Gothic’ the Middle Ages, which it called the Dark Ages, the entire millennium from the fall of Rome in the fifth century CE to the Renaissance in the fifteenth.

Figure 5

Digure 6

Contrasting the perceived uncongenially of the Middle Ages with the perfection of republican and imperial Rome, Gibbon looked back as the inspiration for his Decline and Fall to the moment in his Grand Tour when he sat musing in the ruins of the Forum at Rome, ‘whilst the barefooted friars were singing vespers in the Temple of Jupiter’ (quoted in Lentin and Norman, 1998, p. viii). The contrast between the noble ruins of pagan antiquity and the ‘barefooted friars’ suggested a tension between classical values and the Christian: Gibbon blamed the forces of ‘barbarism and religion’ for their contribution to the fall of the Roman empire (Lentin and Norman, p. 1074).

The German philosopher Kant summed up the Enlightenment view of the Dark Ages as ‘an incomprehensible aberration of the human mind’ (quoted in Anderson, 1987, p. 415). In 1784, defining Enlightenment as ‘man's emergence from his self-incurred immaturity’, Kant argued that people should cease to rely unthinkingly on authority and on received wisdom; they should have the courage to think for themselves. ‘The motto of enlightenment’, he declared, ‘is therefore Sapere aude! Have the courage to use your own understanding’ (Eliot and Whitlock, 1992, p. 305). The motto was taken from Horace.

The classics, then, provided for Enlightenment thinkers not just a standard of artistic perfection for emulation but also an independent set of criteria against which to measure, compare and contrast the past and contemporary world, and a spur to thought and action. To the particular delight of the anti-clerical philosophes, the classics suggested a secular alternative to Christian modes of thought and expression. In their constant assaults on conventional religion, they found in the ancient philosophies of Stoicism and Epicureanism, or an eclectic mix of both, an attraction and a pedigree that predated Christianity and suggested rational or at least dignified alternatives for people to live by – and indeed to die by. In the deaths of Socrates and Seneca, the classics offered a noble tradition of suicide, a mortal sin in the eyes of the Church. The dying Hume, claimed with apparent equanimity and very much in the spirit of the Romans that he had neither fear of death nor belief in a future life. The classics were also used to legitimise modern ideas on society and culture in a way that suggested Enlightenment ideas had universal force and relevance, being rooted in the oldest and greatest of civilisations.

Summary point: for Enlightenment artists and thinkers, classical antiquity provided a standard of greatness, a symbol of power and a secular legitimisation of their own forward thinking.

Exercise 5

Turn now to your AV Notes (click on 'View document' below), which will direct you to watch section 3, ‘The classics’. When you have worked through this section of the video and attempted the exercise in the notes, return to this course.

Click on 'View document' to read the notes and exercise for video 3

Click on the blank screen below to start playing video 3 'The classics'

Transcript: The classics

6 The Enlightenment on art, genius and the sublime

Enlightenment ideas on art and the creative process were deeply influenced by the contemporary veneration for reason, empiricism and the classics. The business of the artist was conceived of as the imitation of nature, and as far as high art was concerned, this process of imitation should be informed by an intelligent grasp of the processes used to produce classical art. The ancients and their art were seen as models in the judicious selection of the most beautiful elements observed in nature, creating forms of ideal or ‘beautiful’ nature that were derived from a distillation of the very best and a filtering out of physical flaws. The leading art critic Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–68) held up Greek statuary for imitation as the embodiment of perfection. Transmitted to the eighteenth century via a robust Renaissance artistic tradition based on the antique, Enlightenment Neoclassicism in its broadest sense attempted not only direct borrowings from the antique (the imitation of architectural motifs, the use of classical drapes to clothe figures, idealised treatment of the human figure based on antique sculpture, reference to sculptural poses), but also an emulation of the order, unity, proportion and harmony felt to underpin all classical art. The principles of classical composition were based on the notion of a clear focus on a central motif (a hero, martyr or saint); grand, unifying (as opposed to sparkling, dappled or disjointed) effects of light and shade that wouldn't distract the eye to the detriment of mental focus on an elevating subject; noble simplicity, balance and symmetry (see Figure 7). You will find in the art of Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825) the expression of a particularly pure form of classical composition.

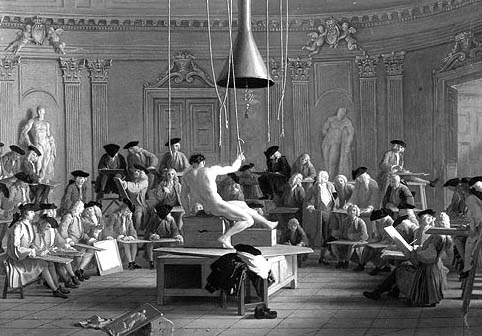

Figure 7

As the century progressed, the dangers of servile imitation, or a formulaic approach to art, were increasingly recognised as the claims for more ‘natural’ art were asserted. A significant body of opinion developed that was critical of artists who simply imitated the art of the past in a way that degenerated into artifice and mannerism. In the 1760s Diderot, who also wrote as an art critic, was among those who insisted that artists should pay more respect to nature. Study of idealised antique statuary and the principles of anatomy and proportion that had informed it remained important to artists, but it was stressed increasingly that respect for these must not exclude or diminish first-hand observation of the human body. Life drawing classes at the academies of art allowed male artists to study the nude, but the human models were normally posed in highly artificial ways that complied with the conventions of antique sculpture; their poses and the positions of their limbs were fixed in the drawing studio by a complex arrangement of ropes, pulleys and blocks (see Figure 8). Theorists called increasingly for less artificial poses and methods of observation.

Figure 8

This growing quest for the ‘natural’ extended to changing views on the status of different genres or subjects in art. While high art, inspired by classical or religious subjects, retained its position at the top of the hierarchies perpetuated by the academies of Europe, there was a growing appreciation of the lower genres of landscape, still life and scenes of everyday life, which required more direct observation of a more natural reality. In landscape art, as you will see, the idealised classical landscapes of the seventeenth-century French artist Claude Lorrain (1600–82) remained extremely influential. But there was also an increasing tendency to place more emphasis on directly observed sketches of the landscape that, while still beautifying nature, allowed for imitation of a greater variety of natural effects. Enlightenment artists and critics were emboldened to demand greater naturalism or realism in art, in both style and subject matter, as a result of the popularity of Dutch and Flemish paintings, which had generated a northern tradition increasingly seen as a real alternative to the classical. In England William Gilpin and other artists and writers interested in what they called the ‘picturesque’ advocated travel as a means of viewing real landscapes and directly observed sketches as part of the process of producing views ‘fit for a picture’. The quest for greater naturalism was seen in France as an antidote to the early eighteenth-century excesses of the Rococo, a specific adaptation or ‘debasement’ of the grand classical style characterised by serpentine curves and asymmetric forms applied mainly to portraiture and to erotic and playful mythological subjects (see Figure 9). In the second half of the eighteenth century, a greater respect for nature was seen as a moral solution to the luxury and corruption of the Rococo's aristocratic patrons.

Figure 9

Given the emphasis on imitation, it is perhaps unsurprising that the Enlightenment concept of the imagination was essentially that of producing new variations on old themes. The imagination was held to combine impressions observed in nature and previous art, but was generally not understood or required to include any great flights of fancy. The pleasure of art lay in the recognition of the familiar reprocessed in ways adapted to modern times. While the Encyclopédie article on ‘Genius’, written by Jean Francois de Saint-Lambert, defined genius as consisting of extraordinary powers of mind, intuition and inspiration transcending mere intelligence, most Enlightenment commentators on aesthetic matters saw such qualities as appropriate to a specific stage of the artistic process (the initial moment of inspiration, the preliminary sketch) rather than as qualities that should dominate or overwhelm. Genius was a quality of mind to be welcomed, but the creative process must also involve reflection, study and observation.

Indeed, many Enlightenment thinkers shared the conviction that good art was largely, though not exclusively, the product of compliance with well-established rules derived from the classics and empirical reason. As Voltaire observed in 1753, ‘I value poetry only insofar as it is the ornament of reason’ (quoted in Furst, 1969, p. 19). Voltaire's aesthetics, like those of most French writers of the eighteenth century, were based on the neoclassical canons of literature laid down in the reign of Louis XIV by such critics as Nicolas Boileau in his Art of Poetry (1674). So while Voltaire was a pioneer in introducing Shakespeare to the European public, he did so with profound reservations and, as it were, holding his nose, arguing that Shakespeare's plays included ‘gold nuggets in a dung-heap’. He presented Shakespeare as a unique genius who succeeded despite such lamentable violations of the neoclassical rules as mixing comic and tragic elements in the same play. Voltaire was in good company in defending the accepted literary canons and explaining ‘genius’ as the exception that proved the rule. Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–92), President of the Royal Academy in London, adopted the same view in relation to art:

Could we teach taste or genius by rules, they would no longer be taste and genius. But though there neither are, nor can be, any precise invariable rules for the exercise, or the acquisition, of these great qualities, yet we may truly say that they always operate in proportion to our attention in observing the works of nature, to our skill in selecting, and to our care in digesting, methodising, and comparing our observations. There are many beauties in our art, that seem, at first, to lie without [outside] the reach of precept, and yet may easily be reduced to practical principles.

(Reynolds, 1975, p. 44)

The artist, in other words, should not let his imagination run away with him. Hume, too, warned of this danger:

The imagination of man is naturally sublime, delighted with whatever is remote and extraordinary, and running without control into the most distant parts of space and time in order to avoid the objects which custom has rendered too familiar to it.

(Quoted in Hampson, 1968, p. 158)

The deeper irony for today's reader is that it was precisely this unconstrained escapism into long ago and far away, the ‘remote and extraordinary’, that was to captivate and characterise the Romantics.

Summary point: Enlightenment ideas on art and the artist were dominated by reason, moderation, classicism and control. However, there was recognition of the elusive quality of original ‘genius’.

If most aesthetic ideas of the Enlightenment emphasised reason and experience, and classified ‘genius’ as something outside the rules, there was one further concept mentioned by Hume, ‘the sublime’, that seemed to strain Enlightenment rationality to its limits. Theorised by Edmund Burke in his Philosophical Enquiry, a sublime aesthetic experience was one that inspired awe and terror in the spectator or reader. The sublime was something literally overwhelming, either because of its enormity (a high mountain, a deep chasm, a blinding light), its infinity (the spiritual or timeless) or its obscurity (a cloud-capped mountain, a floating mist, night, intense darkness) – all, significantly, the opposite of the precise, measured, penetrating ‘light’ of the Enlightenment. When faced with the sublime, the viewer, listener or reader felt a kind of paralysis of the will and of the powers of understanding and imagination. At the same time, as an aesthetic experience (grounded in art rather than reality) the sublime allowed for the thrill of danger without its real consequences. Immensely popular in this context across Europe were the ‘works’ of Ossian, ostensibly a poetic cycle by a Gaelic bard of the third century CE, but in fact the invention of James MacPherson (1736–96), who published his prose ‘translations’ in 1760. Napoleon was among the many devotees of Ossian, as much moved by the tales of legendary heroes in a wild, rugged and primitive northern setting as by Homer's more familiar Greeks and Trojans. This kind of exalted experience was increasingly sought in art and by the late Enlightenment was a dominant aesthetic mode:

It is night. I am alone, forlorn on the hill of storms. The wind is heard in the mountain. The torrent pours down the rock. No hut receives me from the rain, forlorn on the hill of winds. Rise o moon from behind the clouds. Stars of the night, arise!

(MacPherson, Colma's lament from Ossian, quoted in Barzun, 2000, p. 409)

In Mozart's Don Giovanni the sublime emerges in the infernal forces that swallow the main character at the end of the opera, and perhaps in the sublime courage of the man who defies them. The image of Prometheus, the demi-god punished for his defiance of the king of the gods, began to haunt the poetic imagination when Goethe (1749–1832) devoted to it a dramatic fragment and ode (1773). For the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, it was the possession of a non-material soul that allowed people to seize the infinity of the sublime. This sensation of phenomena straining or exceeding the limits of human understanding was later to form the basis of a fully-fledged Romantic aesthetic.

Summary point: in the Enlightenment the theorisation and popularisation of the sublime began to undermine the eighteenth century's otherwise clear emphasis on the knowable, the rational and controllable.

7 The Enlightenment and nature

The sublime was potentially subversive of the Enlightenment mindset, which focused mainly on the power of human intelligence to grasp and explain the natural world, and indeed to discover natural causes of phenomena previously considered supernatural. There were, for example, frequent attempts to demystify the ‘miracles’ narrated in the Bible, since the violation of the laws of nature which a miracle implied was a physical impossibility and a contradiction in terms. The Marquis de Sade was appealing to an established Enlightenment mentality when he declared that there was no need to look beyond the physical world of nature (including human physiological needs), to the spiritual, in order to explain human behaviour. Hume had already popularised the notion that human beings can be understood purely as creations of nature. Enlightenment science and technology sought to open up to scrutiny and harness the power of all aspects of the natural world, while landscape painters and garden designers attempted to prune, beautify and frame nature in ways that emphasised the human capacity to control it. Nature was regarded as an object of investigation rather than a force or attraction in its own right.

When Samuel Johnson visited Scotland with his companion and biographer James Boswell in 1773, he recorded his impressions in A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland.

Exercise 6

Read the following passage on the Highland mountains from Johnson's Journey. How would you describe his attitude towards mountainous regions? In answering this question, it will be helpful to identify key words that betray the emotional colour of Johnson's response.

Of the hills many may be called, with Homer's Ida, abundant in springs, but few can deserve the epithet which he bestows upon Pelion, by waving their leaves. They exhibit very little variety, being almost wholly covered with dark heath, and even that seems to be checked in its growth. What is not heath is nakedness, a little diversified by now and then a stream rushing down the steep. An eye accustomed to flowery pastures and waving harvests, is astonished and repelled by this wide extent of hopeless sterility. The appearance is that of matter incapable of form or usefulness, dismissed by Nature from her care, and disinherited of her favours, left in its original elemental state, or quickened only with one sullen power of useless vegetation.

It will very readily occur, that this uniformity of barrenness can afford very little amusement to the traveller; that it is easy to sit at home and conceive rocks, and heath, and waterfalls; and that these journeys are useless labours, which neither impregnate the imagination, nor enlarge the understanding. It is true, that of far the greater part of things, we must content ourselves with such knowledge as description may exhibit, or analogy supply; but it is true, likewise, that these ideas are always incomplete, and that, at least, till we have compared them with realities, we do not know them to be just. As we see more, we become possessed of more certainties, and consequently gain more principles of reasoning, and found a wider basis of analogy.

Regions mountainous and wild, thinly inhabited, and little cultivated, make a great part of the earth, and he that has never seen them, must live unacquainted with much of the face of nature, and with one of the great scenes of human existence.

(Greene, 1986, pp. 611–12)

Discussion

‘Hopeless sterility’, ‘repelled’, ‘disinherited’, ‘uniformity of barrenness’: these terms betray Johnson's personal aversion to mountains, particularly those stripped bare of vegetation. Although he sees them as among the ‘great scenes of human existence’ (no doubt because of their significance and scale, which as dutiful empirical reasoners we need to see and confirm for ourselves), they emerge as natural features to be shunned by those seeking ‘amusement’ (objects of interest).

Let's pause a moment to consider what Johnson is saying and his mode of delivery, his style. Johnson is the archetypal voice of the Enlightenment. Note the prose: poised, balanced, eloquent, dignified, ‘Augustan’ indeed, combining classical learning (the italicised quotations from Homer) with close observation, and drawing broad, balanced conclusions. The mountains themselves, he says, are of inherently little interest to the thinking man, and from the aesthetic point of view the Scottish mountains, far from overwhelming by their ‘sublimity’, are particularly unattractive, arid and monotonous. The Highlands, not being amenable to agriculture, also lack ‘usefulness’. Johnson's is the view of the city dweller, conscious of the interdependence of productive labour and civilised society (the word ‘civilised’ derives from ‘city’).

Summary point: to the enlightened, wild nature was often a source of discomfort rather than a stimulus to the imagination.

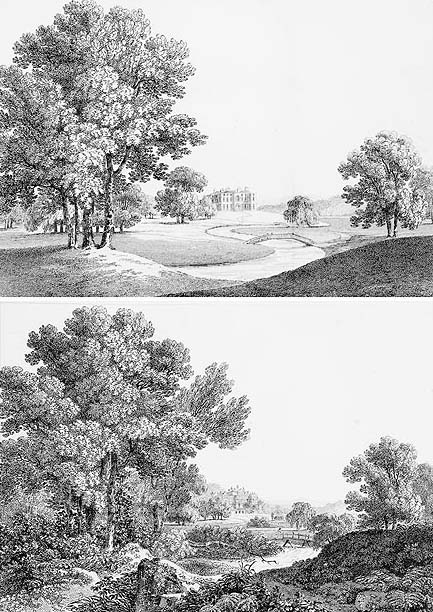

Wild nature, whether in the Highlands or the Alps (the passage of which was considered an unpleasant obstacle on the Grand Tour to Italy), was to be shunned or brought under control. (Napoleon, who crossed the Alps several times on his early campaigns, was as emperor to build mountain passes to facilitate communication with the Italian parts of his ‘French empire’.) The late eighteenth-century fashion for picturesque landscape art and sketching discussed by William Gilpin in his Observations on … the Mountains and Lakes of Cumberland and Westmoreland (1786) and Uvedale Price's (1747–1829) Essays on the Picturesque, as compared with the Sublime and the Beautiful (1794) recommended a judicious selection and arrangement of landscape motifs so that the viewer's eye would be led into the middle distance of a picture and encounter a painted scene in an ordered way. Mountains were often safely relegated to the background. Once again, the emphasis was on control of nature and on the pre-eminence of the human perspective or viewpoint.

In other respects, however, the Enlightenment placed nature in the foreground. In the last section we saw how nature or naturalism became increasingly important to artists. In the same way, nature became increasingly recognised as a guide or force in moral matters. Once thinkers were removed from contemplation of its raw or real state (in, for example, the form of wild landscapes), they elevated its virtues and often overlooked its defects. The most renowned advocate of natural simplicity was Rousseau, who in his Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts (1750) and his Discourse on the Origin of Inequality (1754), as well as in Emile (1762), promoted the idea of natural simplicity and the primitive as a corrective to corrupting wealth and sophistication. (‘Discourses’ were, like ‘Enquiries’ and ‘Dialogues’, an established type of Enlightenment rational enquiry.) Although Rousseau did not believe that human society should revert to a crude primitive state, he did attempt to promote the virtues of a simpler life close to nature, and used the idea of the ‘primitive’ to highlight the deficiencies of contemporary society and point the way to reform. Finding much contemporary culture morally corrupt, he advocated a regenerated culture very different from that of the Parisian salons frequented by the philosophes (see Figure 3). For most Enlightenment thinkers sociability was central to their mission to share ideas, extend knowledge and engage in debate. Rousseau was initially a part of these enlightened social circles, sharing a common background in salon, coffee house, club, academy or learned society, where conversation and ideas flowed freely. Later, however, and partly as the result of arguments born of his own sense of alienation, he distanced himself and began to feel that truth was more likely to emerge from solitary reflection or imaginative reverie, and from the country rather than the city. In his novels (and also in an opera which he composed called Le Devin du village – The Village Soothsayer) he highlighted the virtues of simple people in communion with nature and their own hearts.