Schubert's Lieder: Settings of Goethe's poems

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 19 April 2024, 8:45 PM

Schubert's Lieder: Settings of Goethe's poems

Introduction

This course looks at a selection of short poems in German that were set to music by Franz Schubert (1797–1828) for a single voice with piano, a genre known as ‘Lieder’ (the German for ‘songs’). Once they became widely known, Schubert's Lieder influenced generations of songwriters up to the present day. This course discusses a choice of Schubert's settings of Goethe's poems, and using recordings, the poems (in German with parallel translations into English) and the some music scores. You are not expected to be able to read the music, but even if you are not very familiar with musical notation, you may well find the scores useful in identifying what is happening in the songs.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 2 study in Arts and Humanities.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand Schubert's place as a composer in early nineteenth-century Vienna

understand the place of Schubert in the history of German song and the development of Romanticism

follow the words of songs by Schubert while listening to a recording, using parallel German and English texts

comment on the relationship between words and music in Schubert's song settings.

1 Schubert: introduction

This course focuses on a selection of short poems in German that were set to music by Franz Schubert (1797–1828) for a single voice with piano, a genre known as ‘Lieder’ (the German for ‘songs’). These are miniatures, but in Schubert's hands they become miniatures of an exceptionally concentrated kind. Their characteristic distillation of the emotional essence of a poem illustrates Romanticism at its most intimate. Schubert's Lieder, once they became widely known, influenced succeeding generations of songwriters through to the present day.

A selection of Schubert's settings of Goethe's poems is discussed in this course, with recordings provided for you to listen to. The poems, in German with parallel translations into English and the music scores of four of the song settings are also included. You are not expected to be able to read the music, but even if you are not very familiar with musical notation, you may well find the scores useful in identifying what is happening in the songs.

Exercise 1

Before you read on, play the audio clips below, containing the first two songs, following the parallel text provided. The important thing is to get an initial impression of what sort of material this is.

Click below to listen to 'Heidenröslein'.

Click below to listen to 'Wanderers Nachtlied'.

Click to read these two songs in English and German

Click to view the musical score for Heidenröslein

2 Schubert and Vienna

2.1 Introduction

If Goethe is regarded as the greatest German poet of his time, Franz Schubert (see Figure 1) is generally accepted as the greatest songwriter of the period. But their careers and experience could not have been more different. Unlike Goethe, who lived into his 80s, Schubert died at the age of 31. Goethe's writing career extended from the 1770s, when Enlightenment writing was at its height, to his death in 1832, by which time Romanticism was in full flood. Schubert's important work was concentrated into a period of 15 years at most. Goethe for many years enjoyed esteem and status beyond that of any literary figure in Europe. Schubert was, until long after his death, virtually unknown except to a circle of friends and connoisseurs in and around Vienna. The dominant musical figure in Vienna during Schubert's lifetime was Beethoven, who died in 1827, just one year before Schubert. Schubert greatly admired Beethoven, but probably never even met him, and was merely one of many young composers struggling to earn a living in his shadow. Many of Schubert's large-scale works – symphonies, piano sonatas, string quartets and other chamber works – remained unplayed and unpublished until half a century after his death. The only field in which he did achieve limited success was as a songwriter. A handful of his songs achieved local fame in Vienna during his lifetime, and some of them were modestly successful when published, selling five or six hundred copies while he was alive. But this hardly amounts to ‘success’ for a composer who has since come to be regarded as one of the major musical figures of the nineteenth century. And the songs published in Schubert's lifetime were only a small fraction of the more than 600 which are now to be found in the complete edition of his works.

Figure 1

Schubert's father was a schoolteacher, and Schubert earned a living as a young adult by working as an assistant teacher in his father's school. From 1818, when he was 21, until his death ten years later, he led a precarious existence as a professional composer, depending for income on friends and patrons, and the small amount he earned from publications of his works.

The Vienna in which Schubert lived in the early nineteenth century was full of domestic music-making. But the centre of musical activity had shifted somewhat since the late eighteenth century. Then it was the aristocracy who had supported Mozart and, at the turn of the century, the young Beethoven. By the time Schubert was active as a composer, the middle classes were taking over as the main musical patrons. This change is summed up by the Schubert scholar, Maurice Brown:

Secular music was no longer the product and solace of the aristocratic patron; the prince and priest of the eighteenth century, whose establishments contained bands of musical servants hired to perform chamber and orchestral music, with a composer-servant at their head to provide that music – they were passing. Instead, the wealthy middle-classes were paying the piper, and they called the tune. The publishing-houses were pouring out the songs and dance-music and pianoforte pieces which they loved and asked for. The piano was the centre of this music-making, and in the large and comfortable houses of the merchants and lawyers and civil servants were held these musical evenings, often weekly, to which numbers of guests were invited, and at which part-songs and cantatas, songs, chamber-music, pianoforte duets and so forth were performed.

(1966, p.11)

It was at such gatherings, though occasionally at more public concerts, that Schubert's songs and small-scale instrumental pieces became known in well-to-do middle-class circles in Vienna. Some of his first contacts with these circles were made when he was still a teenager. In 1816 Schubert was asked by a group of law students to write a cantata for the name-day of their professor. The cantata was called ‘Prometheus’, and was reported to be a fine work, though it was lost after Schubert's death. One of the students who sang in the chorus, and whom Schubert met for the first time on this occasion, was Leopold von Sonnleithner, the son of a distinguished barrister, Ignaz von Sonnleithner. The Sonnleithners were one of those prominent families in Vienna who held weekly concerts in their house to a large audience of invited guests. They became Schubert's friends and supporters, his music was often played and sung at their concerts, and they helped to raise money to publish some of his songs. By the 1820s, several households, including the Sonnleithners, were devoting whole evenings to Schubert's works, and these gatherings came to be known as Schubertiads. The first report of such a gathering was made in January 1821:

Franz [von Schober] invited Schubert in the evening and fourteen of his close acquaintances. So a lot of splendid songs by Schubert were sung and played by himself, which lasted until after 10 o'clock in the evening. After that punch was drunk, offered by one of the party, and as it was very good and plentiful the party, in a happy mood anyhow, became even merrier; so it was 3 o'clock in the morning before we parted.

(Quoted in Deutsch, 1946, p. 162)

2.2 Schubert and Johann Michael Vogl

By 1825 Schubert's painter friend Moritz von Schwind was reporting, ‘There is a Schubertiad at Enderes's each week – that is to say, Vogl sings’ (quoted in Deutsch, 1946, p. 401). Schwind names seven regular male members of the group, so even allowing for wives and other unnamed friends it was quite a small gathering. Another report of a Schubertiad at Enderes's the following year mentions that ‘more than 20 people have been asked’ (quoted in Deutsch, 1946, p. 531), and several other gatherings were of similar size. The musical part of the evening was always followed by food and drink, and sometimes dancing, for which Schubert often played the piano. Afterwards some of the group would go on to an inn.

Johann Michael Vogl (1768–1840), mentioned above by Schwind, was a key figure in the success of Schubert's songs on such occasions. Vogl was a celebrated baritone at the Vienna Court Opera who met Schubert for the first time in 1817. He was aged 49, and reaching the end of a successful operatic career. He was renowned for his performances in both Italian and German opera, and three years earlier he had taken part in the premiere of Beethoven's Fidelio. Through the intervention of a friend, Vogl was persuaded to come to Schubert's lodgings to try some of his songs. Vogl sang three songs, including ‘Ganymed’, which Schubert had only just completed. His manner was haughty, and Schubert, as an unknown composer, was somewhat in awe of him. But Vogl was impressed, and soon became a great advocate of Schubert's Lieder, frequently performing them at private and public concerts, often accompanied by Schubert himself – though, since Schubert was not a pianist of the first rank, also by professional pianists on the more public occasions. Despite Vogl's grand manner, he and Schubert became friends. Several times they travelled together during the summer, and Schubert stayed with Vogl on visits to the singer's birthplace, Steyr in Upper Austria. On one trip in 1825, they travelled back via Salzburg, staying at a number of houses on the way and performing to private gatherings.

Schubert wrote a long letter to his brother Ferdinand describing this trip. At Salzburg:

Through Herr Pauernfeind, a merchant well known to Herr von Vogl, we were introduced to Count von Platz, president of the assizes, by whose family we were most kindly received, our names being already known to them. Vogl sang some of my songs, whereupon we were invited for the following evening and requested to produce our odds and ends before a select circle; and indeed they touched them all very much, special preference being given to the ‘Ave Maria’ already mentioned in my first letter. The manner in which Vogl sings and the way I accompany, as though we were one at such a moment, is something quite new and unheard-of for these people.

(Quoted in Deutsch, 1946, pp. 457–8)

This was a partnership important to both of them: it did a great deal to spread Schubert's name as a song composer, and it gave Vogl a second career when he was too old to continue on the opera stage. Ironically, Vogl, already famous in his own lifetime, is now remembered only because of this later association with Schubert.

As Schubert's letter shows, he was delighted with the way Vogl performed his songs. Other writers confirm that he sang with mastery, but sometimes suggest a somewhat conceited and affected manner, as in the following two descriptions:

On 11th November [1823] we had a Schubertiad at home, at which Vogl took over the singing … V was much pleased with himself, and sang gloriously; we others were merry and bright at table …

(Quoted in Deutsch, 1946, p. 302)

Vogl sang Schubert's songs with mastery, but not without dandyism.

(Quoted in Deutsch, 1946, p. 573)

Vogl had a habit of elaborating Schubert's vocal lines, as his surviving copies of the songs confirm. Nowadays, this would be considered shocking, though there is no report that Schubert objected to such liberties, and it is quite possible that this was a general habit among singers of the day. And he had a somewhat mannered habit of playing with his glasses while singing. But he was undoubtedly an important agent in getting Schubert's songs known, and he devoted much of his time to them once he had retired from the operatic stage. In 1823 (two years after Vogl's retirement), Schubert wrote in a letter: ‘He is taken up with my songs almost exclusively. He writes out the voice-part himself and, so to speak, lives on it’ (quoted in Deutsch, 1946, p. 301).

Exercise 2

Click to open Plate 1: Moritz von Schwind, “An Evening at Josef von Spaun’s: Schubert at the Piano with the Operatic Baritone Johann Michael Vogl”, 1868, sepia drawing, Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien. Photo: Bridgeman Art Library

Plate 1 (above) is a famous sepia drawing by Moritz von Schwind, a painter who was a close friend of Schubert. It shows a Schubertiad at the house of Josef von Spaun. It was inspired by a particular evening on 15 December 1826, at which Schubert and Vogl performed more than 30 of Schubert's songs, but was not drawn until 1868. It shows Schubert at the piano, with Vogl sitting beside him performing one of his songs. Figure 2 is a sketch of Vogl and Schubert also by Schwind, one of several preliminary studies for the complete drawing. Figure 3 is a caricature drawing of Vogl and Schubert, with the description, ‘Michael Vogl and Franz Schubert setting out to fight and to conquer’. It was drawn in about 1825, possibly by Franz von Schober, the friend who first introduced Vogl and Schubert in 1817.

Study these three illustrations, and read the following contemporary description of the same gathering, written by Franz von Hartmann, one of those who attended. What do these different pieces of evidence suggest to you about the relationship between Vogl and Schubert, their audience, and the character of a Schubertiad compared with a modern concert?

15th December 1826: I went to Spaun's, where there was a big, big, Schubertiad. On entering I was received rudely by Fritz and very saucily by Haas. There was a huge gathering. The Arneth, Witteczek, Kurzrock and Pompe couples, the mother-in-law of the Court and State Chancellery probationer Witteczek: Dr. Watteroth's widow, Betty Wanderer, and the painter Kupelwieser with his wife, Grillparzer, Schober, Schwind, Mayrhofer and his landlord Huber, tall Huber, Derffel, Bauernfeld, Gahy (who played gloriously d quatre mains [i.e. piano duets] with Schubert) and Vogl, who sang almost 30 splendid songs. Baron Schlechta and the other Court probationers and secretaries were also there. I was moved almost to tears, being in a particularly excited state of mind to-day, by the trio of the fifth March [Op.40 No.5, a funeral march for piano duet], which always reminds me of my dear, good mother. When the music was done, there was grand feeding and then dancing. But I was not at all in a courting mood. I danced twice with Betty and once with each of the Witteczek, Kurzrock and Pompe ladies. At 12.30, after a cordial parting with the Spauns and Enderes, we saw Betty home and went to the “Anchor”, ‘,where we still found Schober, Schubert, Schwind, Derffel and Bauernfeld. Merry. Then home. To bed at 1 o'clock.

(Quoted in Deutsch, 1946, pp. 571–2)

Figure 2

Figure 3

Discussion

The main differences between this Schubertiad and a modern concert performance are obvious enough from the sepia drawing: the audience is small and crammed together very close to the performers. Most of the women are sitting in the front (there are three peering through the doorway on the left), and most of the men are standing behind them. It was an intimate, social occasion compared with most modern performances of Schubert's songs. It is important to remember, however, that the drawing was not done until 42 years after the event. It has a rather stylised appearance, with many of the figures drawn with exaggeratedly emotional poses. Vogl himself gazes at the ceiling, with his chest puffed out, and one hand extended towards the music on the piano, the other holding his glasses. The sketch is much more lively and down-to-earth, as sketches often are. Vogl sits in a more natural way, looking straight ahead, not at the ceiling. In one hand he holds his glasses, as in the finished drawing, but in the other he holds a single sheet of music, rather than extending his arm towards the music on the piano. Since Schubert, in the letter quoted earlier, describes Vogl as writing out the voice-parts of the songs, this is presumably the voice-part of the song he is singing.

In both the finished drawing and the sketch, Vogl is seated to sing, not standing as in the modern concert hall. This suggests not only a less formal relationship between performer and audience than we are used to, but also a more intimate style of performance than that of the modern Lieder singer. There is good evidence that the big, dramatic voices that modern singers are trained to produce are far larger in volume than the voices of the early nineteenth century were. Modern voices have been trained to carry in large opera houses and concert halls, and to be heard over the modern orchestra. In Schubert's day, orchestras were smaller, instruments (including the piano) were quieter than their modern counterparts, and voices had less to compete against. Vogl's singing was probably on a much smaller scale than most of the singing of Lieder to be heard today.

However, Figure 3 certainly suggests that Vogl was a character with a grand manner, as also do some of the descriptions of him. It caricatures the contrast between Vogl, the operatic star, and Schubert, the somewhat shy, diminutive and chubby composer. (His height was 157cm, less than 5ft 2ins, and he was known to his friends as ‘Schwammerl’, a kind of small mushroom.)

Hartmann's description of this Schubertiad makes it clear that the invited guests consisted of a mixture of musicians and artists together with prominent members of the middle classes and a smattering of minor nobility: lawyers, senior civil servants, and a baron. These were the people whose interest had to be aroused, and whose financial help had to be gained, if a composer was to succeed in Vienna in the early years of the nineteenth century.

Plate 2 (below) shows a smaller gathering at the castle owned by Franz von Schober's family at Atzenbrugg, 40 kilometres from Vienna. Schober was a lawyer, and an important member of Schubert's group of friends. It was at Schober's home in Vienna that the first reported Schubertiad (described earlier) took place. Schubert stayed at the Schober family castle three summers in succession (1820–2) and this watercolour by another friend, Leopold Kupelwieser, dates from that period. It was Schober who introduced Vogl to Schubert, and he was himself described as rather a theatrical character. Kupelwieser's painting shows a game of charades being played. Schubert is seated at the piano, a dog by his side. He is reported to have improvised music for his friend's entertainments and dancing on such occasions.

Clickto open plate 2: Leopold Kupelwieser, “The Family of Franz von Schober playing Charades”, 1821, watercolour, Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien. Photo: Bridgeman Art Library

3 Schubert and the Lied

Schubert set to music the words of a wide range of poets, from those who were internationally famous to others who were known only locally and were among his group of friends. Schubert was capable of making a first-rate song out of a mediocre poem, and often did so. But of all the writers he set, Goethe was the one who most consistently inspired him to write songs of startling power and originality. The first of his songs to be widely acclaimed as a masterpiece was his famous setting of Gretchen's song at the spinning-wheel from Faust, composed in 1814 when he was just 17 years old. ‘Erlkönig’ (‘The Erl-king’), which rivals ‘Gretchen’ for the position of Schubert's most famous song, followed in 1815. ‘Ganymed’, one of the songs that so impressed Vogl in 1817, is also a setting of Goethe. In all, Schubert wrote more than 70 songs to words by Goethe – more than one in ten of his output.

As I mentioned in Section 1, the songs that Schubert wrote for one voice and piano are known as Lieder, the plural of Lied. Lied is simply the German word for ‘song’, but it has come to be used specifically to refer to songs in German for voice and piano. Even in England, a concert of such songs is usually referred to as a ‘Lieder recital’. These Lieder became increasingly popular in German-speaking countries in the second half of the eighteenth century. A number of factors encouraged this trend: the growth of the middle classes with an appetite for domestic music-making, the rise of the piano as an instrument in the home, and a growing fashion for songs in a direct and simple style, which developed partly as a reaction to the complexity and artifice of the Italian opera aria with its elements of display and its international star singers.

One important factor in this development was the influence of folk-song, an influence which was also important in Goethe's writing. One of Goethe's mentors as a student was Johann Gottfried Herder, who published two important volumes of folk-songs in 1778, and who encouraged Goethe to collect folk-songs himself. It was Herder who coined the term Volkslied (folk-song) – a word which, in English as in German, has become so commonplace that one hardly ever thinks about the assumptions and meanings that lie behind it. A number of other collections followed, which included examples from across Europe, English and Scottish examples being particularly valued. One of these collections, Brentano and von Arnim's Des Knaben Wunderhorn (Youth's Magic Horn, 1806–8), was dedicated to Goethe, and was described by him as an essential volume for any household. Something of the impulse underlying this interest in folk-song is shown by the preface to a collection by J.G. Naumann (1784):

The times in which dazzling and forced styles found approval are past. Men who had a deeper feeling for the simple tones of nature quickly recognized those errors and took care to avoid the rocks of false taste.

(Quoted in Smeed, 1987, p. 29)

Folk-song was not the only element encouraging writers towards simplicity. In ‘Lieder c.1740–c.1800’, James Parsons points out that German poets and composers throughout most of the eighteenth century emphasised the need for simplicity and naturalness in the writing of songs. The origins of this approach, Parsons argues, go back to a time before Herder's interest in ‘folk-song’, to the Neoclassicism of the 1730s. J.C. Gottsched, professor of poetry at the University of Leipzig in the 1730s, begins his treatise on the art of poetry (1730) with a quote from the Latin poet Horace's Ars Poetica: ‘In short, everything you write must be modest and simple.’ Gottsched instructs the song composer to strive for ‘nothing more than an agreeable and clear reading of a verse, which consequently must match the nature and content of the words.’ Later in the century, writers praised song that was devoted to ‘the noble simplicity of unadorned expressions’ (Johann Peter Uz, 1749) and ‘the touching joy of unadorned nature’ (Christoph Martin Wieland, 1766–7). This emphasis on classical simplicity, Parsons writes, is a counterpoint to the better-known promotion of classical virtues in the visual arts, exemplified by Johann Joachim Winckelmann's praise for the ‘noble simplicity and quiet grandeur’ of Greco-Roman sculpture (1755) (all quotations in this paragraph in Parsons, 2001, p. 669).

But it is important not to be simplistic in our thinking about these calls for ‘simplicity’. In what way is the simplicity of a folk-song like the simplicity of ancient Greek sculpture? Could one really describe the subtle and complex Latin odes of Horace as ‘simple’? It does not take too much thought to realise that such appeals to old or rustic models were more to do with modern writers’ perceptions than with the actual qualities of the models themselves. Writers and musicians of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries sought inspiration in what they saw as the purity of the ancient past and of the unaffectedly rural.

From our perspective, it is easy to see that the ideas of ‘classical’ simplicity, the interest in folk-song, the emphasis on ‘nature’ and the direct expression of feelings, came together in an extraordinary way in the writings of Goethe and Schubert. But this was exceptional: the overwhelming majority of German songs were not the work of great composers, but pleasing and quickly composed settings turned out at high speed for the domestic market, by hundreds of largely forgotten composers, both professional and semi-professional. The sheer quantity of songs published in German-speaking countries reached an extraordinary climax in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. ‘Has there ever been an age more prolific in song than ours’?, wrote the editor of the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung in 1826 (quoted in Parsons, 2001, p. 671). By that date, more than a hundred song collections per month were being published. It was a huge and successful market.

Schubert himself wrote over 600 Lieder. This is often cited as remarkable, and it is indeed a large number to have been written by a composer who lived only to the age of 31. But the sheer number is not the point. There were plenty of composers around 1800 who wrote many hundreds of songs, among them Reichardt and Zelter, both of whom were closely associated with Goethe (as Schubert was not). What is remarkable about Schubert's output is the range and quality of his writing, and the creative imagination which he brought to the musical setting of poetry. These qualities made his songs extremely influential on later composers. A succession of German composers wrote Lieder through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, Hugo Wolf and Richard Strauss, and they all acknowledged Schubert as the pioneering master of the genre.

Ironically, the very quality of his talent limited his success during his lifetime. He composed songs with a great range of mood and complexity, from simple settings much like those of most other composers to highly dramatic and emotionally intense works, often very difficult to sing and to play. These were not suitable for the average amateur performer who regularly bought the latest monthly offerings of the publishing companies. While certain of Schubert's songs quickly became well known and were published soon after he wrote them, the great bulk of his work lay virtually unknown until after his death. This applies not only to songs, but also to his major instrumental works. The ‘Great’ C major Symphony, for example, now acknowledged as one of the most important works of the period, sat with most of Schubert's instrumental compositions in a trunk in the house of Schubert's brother Ferdinand, until the composer Robert Schumann visited him in 1839. Following this discovery, Mendelssohn conducted a performance of the work, in an abbreviated version, later that year in Leipzig. But when he attempted to rehearse it in London with the Philharmonic Society in 1844, they refused to play it. The same had happened two years earlier in Paris under the conductor Francois Habaneck. Many of Schubert's major works similarly suffered from decades of neglect and misunderstanding.

One particularly poignant fact is that Goethe knew nothing of Schubert's talent until it was too late to help him. In 1816 Schubert's friend Josef von Spaun gathered together two volumes of Schubert's Lieder to send to Goethe, hoping that the great man would help in promoting the publication of the young composer's works. The collection included three settings of Goethe's words, which are now among Schubert's most famous songs: ‘Heidenröslein’, ‘Gretchen am Spinnrade’, and ‘Erlkönig’ (all of which we shall be studying in this course). The first volume was sent to Goethe, but he never opened it and it was returned to von Spaun. By this stage of his career, no doubt Goethe was inundated by requests from hopeful composers and writers, as famous authors always are. But it is a sad thought that, if Goethe had realised what the package contained, Schubert's career could have been quite different from that of a struggling, provincial composer with little recognition outside his immediate circle.

4 The songs

4.1 A note on the translations and scores

The German text and a parallel English translation of each of the songs we shall study in this course will be available as attached pdf documents. The styles of translation vary, depending on the style of the original poem. For poems without a regular metre and without a rhyming-scheme, a literal translation of the German is given so that you can follow the original word by word. For poems with regular metre and a strong rhyming-scheme, the translation follows the rhythm and rhyming as closely as possible, in an attempt to convey the impact of the original poem. Inevitably, there are some minor freedoms in these translations. The ‘strict’ translations are ‘The Harper's Songs I’, ‘Prometheus’ and ‘Ganymede’. Freer versions are ‘Wild Rose’, ‘Wanderer's Night Song II’, ‘Gretchen at the Spinning-Wheel’ and ‘The Erl-king’.

At the end of ‘Gretchen’ and ‘Ganymede’, Schubert repeats some of Goethe's lines. In ‘Gretchen’ these are indicated in brackets. In ‘Ganymede’, where the repetition is straightforward, the lines are not repeated in the printed text.

4.1.1 ‘Heidenröslein’ (‘Wild Rose’, 1815) and ‘Wandrers Nachtlied’ (‘Wanderer's Night Song II’, 1822)

The selection in this course begins with songs composed to two of Goethe's best-known poems (several composers other than Schubert wrote settings of them). Schubert's versions are both very short and simple. But they are simple in quite different ways.

Exercise 3

Click the links below to listen to these two songs and look at the musical score of Heidenröslein . First read through the poem in English (click the link below), and then follow the words in the parallel text as you listen to each song. You should find that, even if you have little or no knowledge of German, you will, with a little practice, be able to follow the German words as they are sung, and to keep an eye on the meaning through reference to the English translation. Without attempting any detailed analysis, consider in general terms the main differences in character between the two poems and the two songs.

Click below to listen to Heidenröslein.

Click below to listen to Wanderers Nachtlied II.

Click to read these two songs in English and German

Click to view the musical score for Heidenröslein

Discussion

In the following and subsequent discussions I will offer you my analysis of the question I have posed. If you have not had much experience of trying to analyse music, I realise that you are unlikely to think of everything I suggest. But don't be disheartened by this. If you find it more helpful, you could read through my discussion before attempting the exercise, and then set yourself the task of recognising and understanding my comments. Or you could work through the exercise on your own before seeing what I have made of it.

There are a number of features of the poem ‘Heidenröslein’ which make it very like a folk-song: the simple rhyme-scheme (AB-AAB-CB) which is repeated in each verse, the repeated refrain of the last two lines, and the mock-innocent story of the boy plucking the rose, which is obviously not just about roses.

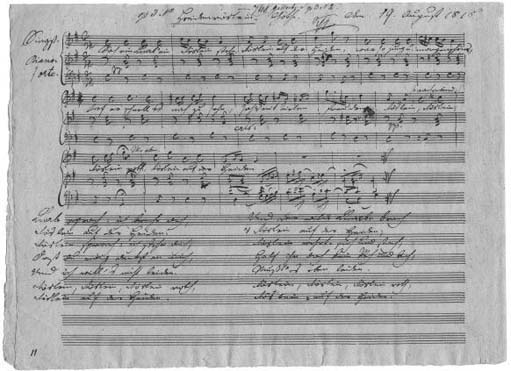

Schubert's setting is also simple, and does not distract from the folk-song style of Goethe's poem. He adheres to the pattern of three verses, repeating the same music for each verse (the musical term for this method of setting is ‘strophic’). In the manuscript (see Figure 4) he just writes the music out once, with the words of the first verse placed underneath the voice-part, and verses 2 and 3 given at the bottom of the page (as in a modern hymn-book). In the published edition, the words of the three verses are all fitted under the voice-part, making it easier to follow words and music together. The piano part consists of a regular pattern of chords, continuing until the singer has finished each verse, and then rounding off the verse with a slightly varied repetition of the singer's last phrase. There are subtleties in Schubert's choice of chords, the most noticeable effect of which is that lines 3–5 of each verse seem to ‘run through ‘without any sense of coming to rest until the end of line 5 (‘Freuden’ in verse 1). This helps to emphasise Goethe's verse structure, in which lines 2 and 5 rhyme.

Figure 4

‘Wandrers Nachtlied’ is simple, but not in the way that ‘Heidenröslein’ is. The poem has none of the feel of a folk-poem. It does rhyme, but the rhyming pattern is not as regular as in a folk-poem: it goes AB-AB-CD-DC (the rhymes in the German are full rhymes; the translation has resorted to half-rhymes for some lines – ‘still/feel, breeze/peace’). There is no division into verses. The relationship between rhyming and rhythm is subtle: the first four lines rhyme AB-AB, but Goethe undermines any sense of regularity by varying the lengths of the lines and by running the sense over from line 4 to line 5.

I think you'll agree that Schubert's setting of ‘Wandrers Nachtlied’ does not sound in the least like a folk-song. It is very slow, with long vocal lines that need the resources of a trained singer to sustain them. The piano part is quiet and deep throughout, with low bass notes emphasising the profound calm and darkness of the poem. It sounds almost like a hymn, but one of great solemnity.

One fundamental difference between these two songs is that ‘Heidenröslein’ is a narrative about a boy, though incorporating some dialogue. ‘Wandrers Nachtlied’ is not a narrative: it is sung by the wanderer himself. When he sings that peace will come soon, he is comforting himself. So the contrast is between, in the first song, a simple story, simply set like a folk-song and, in the second, a song which encapsulates a single moment of reflection, evoking a particular emotional state for its own sake, not as part of a story. We can imagine that there might have been a story, but we have to make it up for ourselves. ‘Wandrers Nachtlied’ is in that sense more Romantic in spirit than ‘Heidenröslein’. It is an example of art directly expressing emotional experience.

The idea of a wanderer expressing his or her own thoughts became a very popular theme in early nineteenth-century poetry and Lieder. A number of composers wrote ‘song-cycles’ using this idea – sequences of songs to be performed continuously, meditating on a journey. These were, in the more subtle examples of the genre, to be understood as analogous to the journey through life, and a meditation on the human condition. The most famous is Schubert's Winterreise (Winter's Journey), written in the last year of his life – a cycle of songs with a predominantly melancholy, and increasingly bleak, character, which can have an overwhelming impact in a good performance.

4.2 Simplicity and complexity

As we have already discovered, the concept of ‘simplicity’ is not a simple matter. We saw earlier in the course that the simplicity of folk-song is not the same as classical simplicity, though both influenced the taste of Lieder writers. ‘Heidenröslein’ and ‘Wandrers Nachtlied’ are simple in quite different ways, both in their poetry and in their music. Many other songs by Schubert are much longer, much more complex, and treat the poetry with much greater freedom. This aspect of Schubert's style, which is now so much appreciated, did not always please his contemporaries.

Goethe himself preferred composers to take a direct approach to setting his poems – direct in the sense that he wanted them to stay close to the structure of his text, and not to indulge in free fantasy and repetition, nor to overlay it with too heavy a piano accompaniment. Poetry and song were closely linked in Goethe's mind – he envisaged the songs in his plays and novels actually being sung, not just spoken, and some were originally published with simple musical settings – and he had clearly stated views on how such songs should be set to music. The composers with whom Goethe worked, and of whom he approved (notably Reichardt and Zelter), took a direct and simple approach to his poems, leaving their structures more or less unchanged, and restricting the piano part to a fairly straightforward accompaniment. This straightforward approach to what German Lieder should be like was shared by many writers of Schubert's time, and for that reason the more subtle and complex of Schubert's settings were not always appreciated by contemporary commentators. Even in the last year of his life, 1828, the publication of a new collection of his songs provoked a reviewer to sum up Schubert's strengths and weaknesses in the following way:

Herr S. knows how to choose poems which are really good (in themselves and for musical treatment) and have not yet been used up either; he is capable and usually succeeds in discovering in each what predominates emotionally and therefore for music, and above all he places that into his generally simple melody, while he allows his accompaniment, which however is very rarely mere accompaniment, to paint this further, and for that purpose he is fond of using images, parables or scenic features in the poems. In both he often shows originality of invention and execution, sound knowledge of harmony and honest industry: on the other hand he often, and sometimes very greatly, oversteps the species in hand, or else that which should by rights have been developed in such and such a piece; he likes to labour at the harmonies for the sake of being new and piquant; and he is inordinately addicted to giving too many notes to the pianoforte part, either at once or in succession.

(Review in the Leipzig Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, 23 January 1828, quoted in Deutsch, 1946, p. 718)

The essence of this rather verbose exposition is an oft-repeated view in the period of Schubert, as it was through the second half of the eighteenth century: that the German Lied requires straightforwardness and simplicity, and that introducing too much complexity, as Schubert was said to do, goes against the spirit of the genre. But, having said that, Schubert's approach varied considerably throughout his career, and depended on the character of the text that he was setting.

4.3 Voice and accompaniment

One thing that is clear from the Lieder we have already considered is that Schubert's writing for the piano is a crucial element of his skill as a songwriter. Sometimes, and throughout his career, he wrote very simple accompaniments, as in ‘Heidenröslein’ – the approach favoured by Goethe and many other writers of the time, who considered that the German Lied should not overload the poem with too much elaboration. Schubert's later version of the ‘Harper's Song’ is more complex, with an introduction and a postlude in the piano, and a more varied style of accompaniment throughout the song.

In many of his Lieder, Schubert uses a device which, though not new, he made particularly his own. This consists of taking a rhythm, or a little melodic phrase (motif), and repeating it in the piano part throughout the song to give it a strong and coherent character. Schubert's particular gift was to find rhythms and motifs which seem to encapsulate some essence of the poem and its mood. His two most famous songs do this: ‘Gretchen am Spinnrade’ (‘Gretchen at the Spinning-Wheel’), and ‘Erlkönig’ (‘The Erl-king’).

4.3.1 ‘Gretchen am Spinnrade’ (‘Gretchen at the Spinning-Wheel’, 1814)

This celebrated song was Schubert's first setting of a poem by Goethe. Written when he was only 17, it was one of the few songs to be sold in quite large numbers during Schubert's lifetime – though he made little money out of it. Robert David MacDonald's translation, taken from his version of Faust, conveys not only the meaning of Goethe's words, with a few liberties, but also the rhythm and something close to the rhyming-scheme of the original. The six concluding lines are in brackets because they are repeated in Schubert's song but not in Goethe's original poem.

The poem and its translation appear below as does the music score of this song.

Exercise 5

Listen to ‘Gretchen am Spinnrade’ by clicking the link below, follow the translation (available by clicking the link below), and consider what Schubert has done to Goethe's poem. In what ways has he remained faithful to the rhythm and structure of the poem, and in what ways has he changed or adapted them?

Click to read the poem

Click to view the score

Click below to listen to Gretchen am Spinnrade.

Discussion

The poem is short and simple. The lines are short, and Gretchen conveys her feelings directly and forcefully.

Is Schubert similarly direct and simple? Yes and no. In one essential way Schubert does remain faithful to the rhythm of the poem. Each line of the poem is very short; it is partly the constant repetition of this rhythm in the poem itself that conveys Gretchen's sense of obsession, of being taken over by her feelings for Faust, of knowing that she cannot escape. Schubert's phrases are also short. Each line of the poem is set to a separate phrase, and even at the climax of the song those phrases are short. In this way Schubert has preserved the detailed structure of each verse of the poem; the short phrases of music, rising twice to a climax, add to the impression of breathlessness which is already in Goethe's poem.

However, Schubert's extra repetition of some of the words alters the broader structure of the poem in fundamental ways. Goethe repeats the opening verse twice, to form a recurring refrain, but he does not return to it at the end. Goethe's original ends with ‘Vergehen sollt'!’ (‘sink and die’). Schubert repeats Goethe's final verse, so extending the climax of the song, and then, after the piano part has quietened, repeats Goethe's refrain one last time. This final repetition of the refrain is made especially poignant by the fact that Gretchen does not complete it: she sings only the first two lines. This has the wonderful effect of making the song sound unfinished – it does come to an end, but the feelings hang in the air, heightening the impression that Gretchen can never escape from them.

Schubert intensifies the effect of this refrain with an internal repetition which is not so obvious. In line 3 of the first verse, he repeats ‘Ich finde’, and he does this each time the refrain occurs. This might seem a small point, but it has the effect of creating a longer phrase than at any other time in the song. Every other phrase in the song is two bars long. Those phrases often form pairs, four bars long, like a pair of lines in the poem. But lines 3 and 4 of the first verse are moulded into one continuous, longer phrase, five bars long (or six, if you count the bar that the piano plays at the end of it). It is not important to know how many bars long the phrases are, though you may like to check my analysis on the score. What is important is the yearning emphasis this continuous, longer phrase throws on those lines: ‘I'll find it never, nevermore’. Because Gretchen comes back to it twice, it seems like the heart of the song. And then at the end, when she fails to reach it, this intensifies the feeling of something unfinished and ongoing.

The other striking feature of Schubert’s song is the piano part. Goethe's stage instruction specifies that Gretchen is at her spinning-wheel. Schubert's accompaniment does not literally sound like a spinning-wheel: the rhythm is quite different. But he has created a musical analogy, with a whirling pattern of rapid notes which repeats constantly, changing pitch and key as the song progresses, but never changing its basic pattern and rhythm. If you look at the piano part in the score, you can see that, in the right hand, the pattern of six notes is repeated throughout the song, only very occasionally being varied. There is also a regular pattern through most of the left hand. This generates not only an effect suggestive of a spinningwheel, but also a sense of something that cannot be escaped. Indeed, as often in Schubert’s songs, it almost seems wrong to talk of the piano part as an ‘accompaniment’. You could equally well say that it is the piano which determines the mood and the structure of the piece, and the voice sings an ‘accompaniment’.

There is one obvious, basic difference between the song and the poem. The song has an enormous emotional range, beginning softly and rising twice to great climaxes. At the first climax, at ‘Und ach, sein Kuss!’, the music stops abruptly after the high note on ‘Kuss’ (‘kiss’), and then restarts quietly and hesitantly. This gives the impression that Gretchen is getting the spinning-wheel going again; but it also conveys a sense of hopelessness, as she realises that her overwhelming passion has doomed her to a sense of loss. The final climax is even higher and more sustained, with the climactic phrase repeated to the words ‘Vergehen sollt’!’ (‘sink and die’), and then the climax dying away as the spinning-wheel slows down, and Gretchen sadly reiterating her half-finished refrain. But is it right to say that the song has a greater emotional range than the poem? Certainly the singer of the song is asked by Schubert to encompass a massive range of volume, from pianissimo at the beginning to fortissimo at the climax, and from low notes at the start to high notes at the climax. Readers of the poem, whether in the context of the play or not, would never do that. It is easy to imagine how ridiculous it would sound if the actor playing Gretchen were to speak or sing it with massive climaxes, as in Schubert's song. But does that mean that the poem is less emotional than the song? Music certainly has its own emotional structures and dynamics, and one of the hallmarks of Romantic music is the use of greater freedom and more extreme contrasts than were used in the time of Mozart.

‘Gretchen’ is a song sung by a female character in Goethe's Faust. Although nineteenth-century singers often sang Lieder which seem intended for the opposite sex, only women are reported to have sung this song in Schubert's lifetime. There is no record, as far as I know, of Vogl singing it. A number of women singers were important in promoting Schubert's songs specifically for women. Among them were the much-loved actress Sophie Miiller, who sang his songs ‘most touchingly’, sometimes with Schubert himself accompanying (Deutsch, 1946, p. 403), and a pupil of Vogl, Anna Milder, for whom Schubert wrote the lovely song with piano and clarinet, ‘The Shepherd on the Rock’.

4.4 ‘Erlkönig’ (‘The Erl-king’, 1815)

Exercise 6

Before continuing with the course, read the English translation of ‘Erlkönig’ by clicking on the link below. The translation attempts to stay close to the rhythm and rhyming-scheme of Goethe's poem, and should therefore give you a fairly good idea of the character of this famous ballad.

Click to open the words to ‘Erlkönig’

Schubert wrote ‘Erlkönig’ only a year after ‘Gretchen’. Schubert's friend Josef von Spaun left a description of how he wrote ‘Erlkönig’ on 16 November 1815, after reading Goethe's poem:

We [von Spaun and Johann Mayrhofer] found Schubert all aglow reading the ‘Erlkönig’ aloud from a book. He walked to and fro several times with the book in his hand; suddenly he sat down, and in no time at all the wonderful ballad was on paper. We ran to the Konvikt [the school where they had both been pupils] as Schubert had no piano and there, the same evening, the ‘Erlkönig’ was sung and wildly acclaimed. Old Ruzicka [Schubert's music teacher at the school] then played through all the parts himself carefully, without a singer, and was deeply moved by the composition. When one or two of the company questioned a recurring dissonant note [at the boy's cries of ‘Mein Vater'], Ruzicka played it on the piano and showed them how it matched the text exactly, how beautiful it really was and how happily it was resolved.

(Quoted in Fischer-Dieskau, 1976, pp. 48–9)

The Schubert scholar Maurice Brown argues convincingly that this story must contain some elements of myth. It is well established that Schubert did have a piano, so there would have been no need to rush to the school (nearly an hour's walk away). And even if the song had completely formed itself in Schubert's mind, it would have taken him a long time to write it all down sufficiently clearly for his teacher to examine it in detail (a slightly longer song, composed in the same year, has a note on the manuscript that it took Schubert five hours to write). Brown suggests that the story is probably constructed from separate events which have been brought together – finding Schubert pacing up and down with Goethe's text, the completion of the song, and the showing of it to Ruzicka (1966, pp. 46–7).

Whatever the truth of Schubert's writing of ‘Erlkönig’, it scored an immediate success, and is one of the few of his songs that became well known during his lifetime. It was already one of Goethe's best-known poems, and several composers had set it to music, including Goethe's associates Reichardt and Zelter. Goethe took an old German legend about an evil goblin that abducts children, and wrote it in the style of a Scottish ballad. Ballads were one of the forms of folk poetry that Goethe's mentor, Gottfried Herder, helped to make popular in Germany. One of the inspirations for this fashion was Bishop Percy's Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765), which included one of the most famous old Scottish ballads, ‘Edward’ (of uncertain origin). Herder had translated ‘Edward’, and Schubert set that translation as a song too.

Goethe's ‘Erlkönig’ was always intended to be sung, and it occurs in his play Die Fischerin (The Fisherwoman, 1782). The stage direction reads:

Scattered under tall alder trees at the edge of the river are several fishermen's huts. It is a quiet night. Round a small fire are pots, nets and fishing-tackle. Dortchen sings at her work: ‘Wer reitet so spat … ‘

(Quoted in Fischer-Dieskau, 1976, pp. 48–9)

The actress who played the part of Dortchen at the premiere wrote her own simple eight-bar melody, which she repeated for each verse. The effect must have been somewhat like that of Patti Clare, who plays Gretchen in the recording of Faust on Audio 6 (track 6), humming ‘A king of a Northern fastness’ as she undresses. Goethe stated his own view on the realisation of such songs where they occur in his dramas:

The singer has learned it somewhat by heart and recalls it from time to time. Therefore these songs can and must have their own, definite, well-rounded melodies which are attractive and easily remembered.

(Quoted in Fischer-Dieskau, 1976, pp. 48–9)

Schubert has lifted the song completely out of this original dramatic context, setting the drama of the ballad itself with extraordinary power.

Exercise 7

Listen to ‘Erlkönig’ in the two recordings, one sung by a man, the other by a woman. Follow the poem and its translation as you listen. Then consider the following questions:

-

How does Schubert use the piano part to conjure up the scene?

-

How does Schubert distinguish between the three speakers – the father, the child, and the Erl-king? Consider, in particular, the lengths of the phrases that they sing, and the pitch at which they sing them.

Click below to listen to Erlkönig (male version).

Click below to listen to Erlkönig (female version).

Click to open the words to ‘Erlkönig’

Discussion

1. As in ‘Gretchen’, it is the piano that sets and maintains the scene vividly. The right hand hammers away relentlessly at repeated notes, and continues to do so through most of the song. (From the second bar onward, diagonal strokes through the stems of the notes indicate that the pattern of bar 1 is to be repeated – a conventional abbreviation.) A little rushing figure in the bass is also repeated again and again. Even before the mention of horse-riding in the first line of the poem, a feeling of urgency, perhaps even fear, has already been established. This is typical of Schubert's way of establishing tone and atmosphere: he takes an element of the poem, in this case the rhythm of a horse galloping, and uses it to create a motif which vividly establishes the mood of the poem, and provides a sense of unity through the whole of the song.

2. This is more difficult to answer, because of the way that singers add characterisation of their own to what Schubert has written. Naturally a singer will tend to sing the father's passages in a solid, manly way, the child's part in a lighter, more childish tone, and the Erl-king in a wheedling and spooky manner. It also makes a difference whether it is a man or a woman singing it. Since all the characters in the song are male, a male singer tends to give more sense of actually impersonating the characters, particularly the father. A woman singer inevitably tends to give more the impression of telling the narrative, with less sense of actually being the different characters. Nowadays it is more often sung by a man than by a woman, though both male and female singers performed the song in Schubert's lifetime, and of course Goethe originally intended the ballad to be sung by an actress on the stage. And it was a woman, Wilhelmine Schroder, who sang it to Goethe after Schubert's death and persuaded him that it was a great song (too late to benefit Schubert, alas). There is even a report of Schubert taking part in a performance with three singers while he and Vogl were staying with a musical family on a visit to Steyr: Schubert sang the part of the father, Vogl that of the Erl-king, and the 18-year-old daughter of the family that of the boy.

After that preamble, how does Schubert's music distinguish between the father, the boy, and the Erl-king, quite apart from how the singers characterise them? The most striking difference between them is that the Erl-king is the only one of the three who gets a real, continuous melody. And, until the very end of his part, where he threatens force, his melodies stay in major keys. By contrast with the Erl-king, the boy and the father have only short, disjointed phrases, almost always in minor keys. The Erl-king's smooth melodies sound sweet and agreeable, and in the context of the song, that is what makes them sinister. He sounds at ease, and his very fluency suggests that he is the one in control of the situation. The Erl-king's lines are also the only parts of the song where the hammering of the piano part relents, switching to a more easy-going rhythm. You can see this in the score: at ‘Du liebes Kind’, in the right hand of the piano, Schubert leaves out the first of each group of three notes, and has the bass playing a short note on each beat, as if the horse has settled into a comfortable rhythm. At the Erl-king's next entry, ‘Willst, feiner Knabe’, the right hand of the piano stops its hammering altogether, and plays easy-going arpeggios, up and down, giving almost the lulling effect of a cradle-song. And the third time the Erl-king sings, the bass of the piano remains static, playing long notes, while the right hand continues its hammering, but pianissimo. This gives a great sense of tension, which then bursts out at the boy's final cries of ‘Mein Vater’, where Schubert gives the marking fff (even louder than fortissimo).

It was the Erl-king's lines that most struck contemporary listeners to the song:

The cradle-spell that speaks from the melody, and yet at the same time the sinister note, which repels while the former entices, dramatises the poet's picture.

(Deutsch, 1946, p. 254)

The German novelist Jean Paul Friedrich Richter (known as Jean Paul) was reported to be particularly moved by the Erl-king's passages in the song: ‘the premonition of secret bliss, suggestively promised by the voice and the accompaniment, drew him, like everyone else, with magic power towards a transfigured, fairer existence’ (quoted in Deutsch, 1946, p. 511).

The father's short phrases are pitched quite low in the singer's voice, and that adds to the impression of a man who is at least trying to remain calm, and cannot see what his son can see. If he is alarmed, he is certainly not going to show it. The boy's phrases are also short, but they are higher in pitch, and they get higher as the tension mounts. His cries of ‘Mein Vater, mein Vater’ are pitched a step higher each time: up to E flat the first time, F the second time, and G flat the third and last time, the highest note in the whole song. Each time this phrase occurs, it clashes discordantly against the relentlessly hammered-out notes in the right hand of the piano part (the touch that Schubert's teacher Ruzicka is said to have admired). And each time the phrase is exactly the same. This, together with the rising pitch, the dissonance and the sudden return to the hammering of the piano, gives a vivid sense of increasing desperation.

The ending of the song is dramatic in a subtle way. After the climactic cries of the terrified child, and then the father's accelerating gallop, they finally reach home. The climax of the story is delivered quietly and simply: the boy was dead. The extremely ‘undramatic’ setting of this line is extraordinarily effective. Goethe has already given the clue to it, by switching for the first and only time in the poem to the past tense. If he had written ‘the child is dead’, it would have had quite a different effect. By writing ‘the child was dead’, the narrator steps out of the story, as if closing the book and saying, ‘I don't have to tell you the rest. Of course the boy was dead.’ Schubert's underplayed setting of this ending enhances that effect.

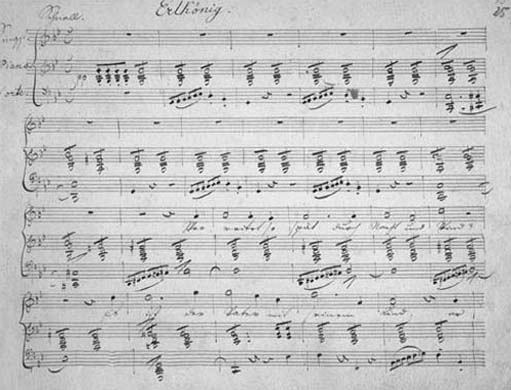

Schubert wrote several drafts of this song before arriving at the version which is now always performed. (This in itself counts against von Spaun's story of Schubert dashing the perfected song down at one sitting.) Most of the others are different in fairly small ways. In all of them, the beginning is marked pianissimo, whereas in the final version it is forte from the start so that the song begins straight away with the emphatic pounding of the horse's hooves. One version has a more fundamental difference, and the first page of Schubert's manuscript of it is shown in Figure 5. As well as having the soft opening, it simplifies the ferociously difficult piano part, giving the right hand only two notes per beat instead of three. This easier version is never played nowadays. But it is in this form that Schubert himself used to play it (he was not a great virtuoso pianist, unlike Beethoven), and it was this version that was sent to Goethe in the package that the poet never looked at. The opening bars of this simplified version of the piano part are played on audio link below.

Click below to listen to Erlkönig, opening bars of Schubert's simplified piano-part (Robert Philip, piano).

This manuscript also shows that Schubert used a shorthand to save time when writing. As in the final version of ‘Erlkönig’, the repeated notes in the right hand of the piano part are written out only at the beginning. After that, he writes a succession of minims (long notes) with a diagonal stroke through them, to indicate that each note is to be subdivided in four, as in the first bar. Does this make it more likely that Schubert's first draft could have been ready ‘in no time at all'? Perhaps.

Figure 5

‘Erlkönig’ ‘was the first song by Schubert that Vogl sang at a public concert, in a theatre in Vienna in 1821. Schubert accompanied him at the rehearsal, and was asked by Vogl to add a few bars in the accompaniment so that he had enough time to breathe. It is not clear whether these extra bars were incorporated into the published version that we now know. Vogl's performance at the concert was a great success, and was encored. A review reported that ‘[s]everal successful passages were justly acclaimed by the public’ (quoted in Deutsch, 1946, p. 166), which suggests that the audience applauded during the performance, more like a modern jazz audience than the silent audience at ‘classical’ concerts. (Many reports during the nineteenth century indicate that this was quite normal in concerts of the time.)

4.5 Two mythological songs: ‘Prometheus’ (1819) and ‘Ganymed’ (1817)

Goethe's poem ‘Heidenröslein’, with which we began, is a mock folksong; ‘Erlkönig’ is a mock ballad along the lines of Scottish models. They are, so to speak, poems in fancy dress. ‘Prometheus’ and ‘Ganymed’ are songs on subjects from ancient Greek myth, but they are in no way imitations of ancient classical models. In these two poems Goethe has taken myths and created modern meditations on them of startling, but quite distinct, kinds.

4.5.1 ‘Prometheus’

Both the poem and the song are quite different from the others considered in this course. The poem does not rhyme, and its rhythmic patterns are irregular. It is more like an extract from a drama than a conventional poem – and indeed it comes from a play that Goethe began writing in 1773 and never finished.

Prometheus was, in ancient Greek mythology, one of the Titans, who created the human race out of clay. Zeus, the king of the gods, tried to destroy humanity by denying them access to fire. Prometheus saved them by stealing the fire back. For this offence Zeus condemned him to be chained to a mountain-top, where his liver was pecked out each day by an eagle and regrew each night. The myth of Prometheus attracted a number of writers and musicians of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Shelley wrote a verse drama on the subject; Beethoven wrote music for a ballet called The Creatures of Prometheus. Schubert wrote a substantial cantata on Prometheus in 1816, which had several successful performances during his lifetime, but was lost after his death (this was the cantata written for the name-day of a law professor, and which gave him his entree to the Sonnleithners' weekly concerts).

In Goethe's drama, Prometheus delivers this speech in his smithy. Schubert's song is like a miniature cantata, or perhaps a scene from an opera. It takes the form of a short, dramatic monologue – a form which is often referred to by musicians by the Italian term scena.

Exercise 8

Click the link below to read the poem ‘Prometheus’. How would you describe the substance and tone of what Prometheus is saying? Then play the performance by clicking the audio link and follow the words. In what way is Schubert's setting like a scene from an opera? How does he characterise each section of the poem?

Click to read the poem ‘Prometheus’.

Click below to listen to Prometheus.

Discussion

The predominant tones of the poem are defiance and revolt. But Prometheus does not merely defy the king of the gods: he views him and the other gods with disdain, declaring that they survive only because credulous fools continue to believe in them. He glories in the fact that he has achieved what he has without the help of the gods, and he ends by extolling the full range of human experience, from suffering to joy.

This is a poem of defiance against the rule of gods, and in praise of human accomplishment and human emotional experience. It is very much in tune with the anti-religious sentiments of much Enlightenment writing, and it places a Romantic emphasis on the primacy of the emotions.

Schubert's setting sounds somewhat like a scene from an opera because much of it is written in recitative, the operatic style which can also be found in Mozart's Don Giovanni, in which the freedom of the vocal line comes close to the rhythms of speech. If you imagine it accompanied by orchestra rather than piano, it is close in style to the accompagnato recitative that Mozart uses from time to time.

Schubert's scena has no obvious formal structure. Though it is in sections, they do not repeat – it is through-composed. It has the character of a psychological drama, emphasising the emotional force of each part of the poem as it occurs. But the song nevertheless falls into distinct and contrasted sections. As in ‘Gretchen’ and ‘Erlkönig’, it is the piano which both sets the tone and drives the song forward. The assertive rhythm which begins the song punctuates the opening section from time to time, giving a coherent sense of defiance to a passage which would otherwise seem like nothing more than a piece of speech set to music. Schubert continues this section through to the first two lines of the second verse in the original, so shifting the break by two lines. Then, at ‘Ihr nähret kummerlich’ (‘Meagrely you nourish …’), the tone changes completely. The sliding harmonies in the piano give the passage a smooth, almost creepy character, perhaps intended to be ironic.

At ‘Da ich ein Kind war’ (‘When I was a child …’) the piano adopts a walking tread, giving a sense of narrative. The voice reaches up at the description of the young boy gazing up at the sun, and the ‘ear to listen’ and the ‘heart to pity’ are set to high, plaintive phrases. This is abruptly interrupted by fierce chords at ‘Wer half mir’ (‘Who helped me …’), returning to the mood of the opening. Then the pace increases at ‘Ich dich ehren?’ (‘I honour you?’), with an impatient-sounding, lurching rhythm in the piano. And the scene ends magnificently, with Prometheus's final shout of defiance, at ‘Hier sitz’ ich’ (‘Here I sit …’), punctuated by forceful chords, like a yet fiercer version of the rhythm with which the song began.

Unusually, the song ends in a different key from its beginning. After the opening bars, the music settles into G minor for the first entry of the voice. The final section, from ‘Hier sitz’ ich’, is in C major. This absence of any formal structure of keys adds to the impression of a song which proceeds freely from one mood to the next.

This unusual informality of structure is something that Schubert exploits to even more striking effect in the last song we shall consider, ‘Ganymed’.

4.5.2 ‘Ganymed’ (‘Ganymede’)

‘Ganymed’ is another through-composed setting of a poem inspired by ancient Greek mythology. Ganymede was a boy of exceptional beauty, and Goethe's poem describes the feelings of the young lad as he is transported up to heaven by Zeus to become cup-bearer to the gods.

Like ‘Prometheus’, this is a freely written poem, with no consistency in the length of lines nor any formal metrical scheme. There is only one rhyme (‘Nachtigall’ and ‘Nebeltal’ in lines 18–19), and there are only occasional suggestions of half-rhymes (in the first verse there are ‘Liebeswonne’, ‘Warme’ and ‘Schone’, which have enough similarity to sound associated).

Exercise 9

Click the links below to read the poem ‘Ganymed’ and its translation, and then listen to the song. What has Schubert done to Goethe's poem? Does the combination of words and music suggest further similarities with ‘Prometheus’, or with the other songs you have studied?

Click to read the poem ‘Ganymed’.

Click below to listen to Ganymed.

Discussion

Perhaps the most obvious similarity to ‘Prometheus’ is that the poem is written in the first person. The two poems/songs are expressions of personal feelings. But unlike Prometheus, who is raging against the gods because of past events, Ganymede is expressing his feelings while the most important event of his life is actually taking place. In this sense, he has more in common with Gretchen at her spinning-wheel (though even she is describing her feelings about what has already happened).

Another feature which ‘Prometheus’ and ‘Ganymed’ share is that the music, like the poems, is extremely free. About ‘Prometheus’ I wrote that Schubert's setting has no obvious formal structure and that it has the character of a psychological drama, emphasising the emotional force of each part of the poem as it occurs. The same applies to ‘Ganymed’.

As in several of the songs we have discussed, Schubert has been rather free in the pacing of ‘Ganymed’, dividing up Goethe's verses where they are continuous, and continuing where they are divided. The first eight lines are continuous, as in Goethe, and Schubert emphasises the effect of ‘Unendliche Schone’ (‘Infinite beauty’) by drawing the phrase out, giving several notes to a syllable for the first time in the song. In the poem, the next two lines (‘Dass ich dich …’) stand on their own, separated from what follows. But Schubert ignores this, carrying straight on for four lines to a gap at ‘Lieg ich, schmachte’. Then he introduces a gap after another two lines (’… an mein Herz’), another gap three lines later (after ‘… Morgenwind’), and another, coinciding with the end of Goethe's verse, at ‘… aus dem Nebeltal’. Schubert has used these gaps in the vocal line to emphasise the sense of ecstatic calm in the poem, as if Ganymede is looking around him, drinking everything in. There is a charmingly naive touch just before the mention of the nightingale, where, during the pause which Schubert has introduced in the vocal line, the piano plays trills to suggest the bird's song.

From ‘Ich komm …’ the character of the piano part changes: the rhythm becomes insistent and staccato, and Schubert gives the instruction ‘un poco accelerando’ (‘accelerating slightly’). There is a distinct sense of ‘We're off’. The song drives through, reaching two climaxes. The second climax is achieved by repeating the last seven-and-a-half lines of the poem, and then repeating again the final cry of ‘Alliebender Vater!’ (‘All-loving father!’). This repetition is certainly taking liberties with the poem, but the changing character of the music is, one could argue, simply a response to what is already in the verse, as the lines and phrases become shorter and more urgent towards the end of the poem.

As in several of the songs we have studied, it is the piano which sets the mood, the pace and the rhythm as the events unfold, with the voice, so to speak, floating on top of the piano part – almost as if the voice is the ‘accompaniment’, as in ‘Gretchen’. A big difference between ‘Ganymed’ and ‘Prometheus’ is that, whereas ‘Prometheus’ falls into distinct and contrasted sections, ‘Ganymed’ does not. It all flows smoothly on, and even when the voice pauses, the piano continues. This helps to convey the impression of events unfolding which are not within Ganymede's control – the piano, like Zeus, sweeps him away.

As in ‘Prometheus’ and ‘Gretchen’, we are not told the story in the poem. It is as if the poet and composer have thought ‘What would it be like to be Ganymede/Prometheus/Gretchen in this situation?’, and have sought to convey that directly, assuming that the audience would know the stories from which these characters come (and Goethe and Schubert could assume some knowledge of classical myths in the well-educated circles to whom their work was principally addressed). This is very different from the narrative of ‘Erlkönig’, in which the song tells the whole story, as well as conveying the feelings of the characters in it.

Schubert ends the song with six bars of the piano, rising higher and higher, pianissimo. Like the song of the nightingale earlier, this has an effect which is both powerful and naive: it conveys both a strong sense of mystery and the suggestion of Ganymede physically disappearing up into heaven.

More than in any of the other songs we have discussed, I would say that, by the end of ‘Ganymed’, we have the sense of having travelled a long way since the song began. There is one particular musical reason for this: as in ‘Prometheus’, the song ends in a different key from the beginning. It starts in A flat major and ends in F major. During the song, the music progresses through a variety of keys so gradually that the listener is not necessarily aware of how far from the original key it has travelled. But if you replay the beginning of the song immediately after listening to the ending, you will hear the contrast between the F major of the ending and the A flat major of the beginning.

5 Conclusion

Robert Wilkinson (2005) has suggested that Romanticism in the end became ‘the dominant view of art in Europe, and we are to this day its heirs’. This is nowhere truer than in song. Even if you have never encountered German Lieder before, you may have been struck by how the emotional directness of Schubert's writing seems like something familiar from much more recent times. The attempt directly to express emotional experience in poetry and in song, often without explanation or narrative, is characteristic of Romantic writers and composers. Of course, poetry and music had sought to express emotions for centuries before Goethe and Schubert. There have, for example, been love-songs and love-poetry since ancient times. But concentrating solely on the essence of the moment is a characteristically Romantic thing to do, and in the field of music it was to be one of the central features of song-writing through the nineteenth century into the twentieth. One could go so far as to say that the modern popular love-song, from American writers of the 1920s and 1930s such as Cole Porter and George Gershwin through to rock and pop songs of the twenty-first century, are later developments from this intense fusion of poetry and music that was created in the early nineteenth century.

An important element in the drive towards directness and ‘simplicity’ in song was the interest in what Goethe's mentor Herder called ‘Volkslied’ (‘folk-song’). In the Introduction to this course I said that this term is now so commonplace that we rarely consider its underlying implications. The concept of a ‘folk-song’ suggests that the words and music have come from ‘the people’ rather than from an author and composer. The anonymity of folk-song is taken to be a virtue in itself, as if it has sprung from the soil. Of course, music and poetry do not actually arise like that; someone, sometime, thought up the words and the tune (though it is characteristic of folk-songs that they are passed down through oral tradition, and different versions often result). The idea that simplicity and naturalness in music and the arts generally were to be preferred to the elaborate and artificial has connections with Enlightenment ideas about nature and the concept of the ‘noble savage’. But by the end of the eighteenth century this elevation of the simple and the natural was taking on a new dimension that can be seen as Romantic, because of its association with individual feeling and experience. In England Wordsworth was its chief exponent, especially in his Lyrical Ballads (1798). In Germany Goethe's supremacy in this field helped to fuel the association of ideas of purity, truth, nature and simplicity with German nationalism, an increasingly powerful force throughout the nineteenth century. The simpler kinds of Lieder, which Goethe preferred, remained close to the model of folk-song. Schubert sometimes wrote Lieder like that throughout his career (as in ‘Heidenröslein’), but he also stretched the concept of the Lied in highly adventurous and imaginative ways.

I used the term ‘psychological drama’ to describe Schubert's settings of ‘Prometheus’ and ‘Ganymed’ (a description that could already be applied to Goethe's poems). One particular example of this approach is ‘Erlkönig’, which is both a ballad and a horror story. Horror stories in various guises became very popular in the early nineteenth century. The fascination with the ‘Gothic novel’, often with medieval settings and evoking the supernatural, reached a peak in England in the early nineteenth century. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein was written in 1818, three years after Schubert's setting of ‘Erlkönig’. In opera, Weber's Der Freischiitz (1821), a story involving the devil and magic bullets, set a fashion for operas with a supernatural element. Of course, this idea was not entirely new: Mozart's Don Giovanni culminates in the spectacular intervention of the dead Commendatore from beyond the grave. Goethe's Faust, similarly, is a modern reworking of a medieval story of a pact with the devil.

Schubert's particular contribution to this field was to create Lieder that drew out with extraordinary intensity the emotional situation of those overtaken by supernatural forces. In another famous song, ‘Der Doppelganger’ (1828, to a poem by Heinrich Heine, one of the most important German Romantic poets), a man visits the house of his former sweetheart at night, to be confronted by his own ghost. Schubert makes of this a song of terrifying power.

Even when not dealing with the supernatural, Schubert is frequently grappling with the inner struggles and resolutions of the human mind. The defiance of Prometheus, the ecstasy of Ganymede, the anguish of Gretchen, the calm resignation of the Wanderer, all are expressed in music so subtle and expressive that one has a sense that it is not merely beautiful, but is somehow conveying insights into the human condition.

An important Romantic element of Schubert's method is his freedom with traditional musical forms and procedures. The ‘rules’ of setting verse have always been flexible in practice. Goethe's preference for adherence to the structure of the poem only went so far, as the settings of Zelter demonstrate. Composers before Schubert, notably Beethoven, stretched the conventions of word-setting. But Schubert went further than any previous composer in giving his imagination free rein, moulding the possibilities of the words in ways that sometimes take them far from their original structure as poems. It was not only in his songs that Schubert did this. His way of writing large movements in his instrumental works is extremely free. Some of his late works, such as his last String Quartet in G major and the second Piano Trio in E flat, had to wait until the second half of the twentieth century before their extraordinary qualities were fully appreciated. Before that time they were often described as ‘curate's eggs’, works with marvellous music in them, but too long and somewhat disorganised in their construction.