Goya

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 19 April 2024, 3:25 AM

Goya

Introduction

What influenced Goya? Did Napoleon's invasion of Spain alter the course of Goya's career? This course will guide you through the works of Goya and the influences of the times in which he lived. Anyone with a desire to look for the influences behind the work of art will benefit from studying this course.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 2 study in Arts and Humanities.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

recognise what influenced Goya

understand the relationship between Napolean and Goya

feel more confident as an independent learner.

1 Background information

1.1 Introduction

An interesting analysis of Napoleon's involvement in Spain is provided by Stendhal in A Life of Napoleon, chapters 36 to 43. Stendhal argues that Napoleon's basic error was to see Spain as susceptible to the imposition by the French of the kind of enlightened reforms which had been welcomed elsewhere in Europe. Stendhal particularises, in a way characteristic of Romantic writers, on what he considers a highly distinctive Spanish national character, which in his view explains the hostile reaction to Napoleon's intervention. ‘Cowardly despotism’, ‘rogues’, ‘idiots’, ‘stupid’ ministers, a people not yet ready to enjoy liberty – these are among the forces Stendhal names as resistant to the (beneficial) government reforms Napoleon sought to introduce.

Figure 1

1.2 Napoleon and the Spanish imbroglio

Napoleon later admitted that his intervention in Spain in 1807 was among his worst mistakes. He referred to it as ‘the Spanish wasps’ nest’ or ‘the Spanish ulcer’, which divided and exhausted his military strength. While Napoleon probably intended to annex the Iberian peninsula to his French empire in any event, his immediate involvement arose from his decision in November 1806 to impose the Continental Blockade or European boycott of British goods, in the hope of defeating Britain by means of an economic stranglehold. (After Nelson's victory at Trafalgar in 1805, Napoleon accepted that he could not defeat Britain at sea.) In 1807 he sent French troops through Portugal with the co-operation of the corrupt Spanish minister, Manuel Godoy (‘the Prince of Peace’), in order to close Lisbon to British trade, enforce the Continental Blockade and break Britain's links with her ‘oldest ally’.

Spain was France's ally against England and Portugal, but much of Spanish opinion in this impoverished and profoundly Catholic country was hostile to the French Revolution and to the Enlightenment as well as to the burdens of the French alliance. (The Spanish as well as the French fleet was destroyed at Trafalgar.) Napoleon was contemptuous of the Spanish royal house of Bourbon (descendants of Louis XIV): the feeble and decadent King Charles (Carlos) IV, his wife Maria Luisa (whose lover was Godoy) and their son Ferdinand (Prince of Asturias), who conspired against his father. Charles got wind of this and placed Ferdinand under arrest in October 1807, but in March 1808 a revolt of Ferdinand's supporters at Aranjuez ousted Charles, Luisa and Godoy from power. Ferdinand acceded as King Ferdinand VII.

Taking advantage of the presence of French troops in the heart of Spain and of these dissensions within the reigning house, Napoleon lured the Spanish royal family to France, ostensibly to mediate between Ferdinand and his parents. At a meeting at Bayonne, however, Napoleon placed them all under house arrest and browbeat both Charles and Ferdinand into renouncing the Spanish throne in favour of Napoleon's elder brother, Joseph Bonaparte. Charles, Ferdinand and Godoy went into exile in France.

Napoleon's insult to Spanish pride provoked a violent popular reaction which spread across the country. Anti-French riots at Madrid on 2 May 1808 (dos de mayo) were suppressed on 3 May (tres de mayo) by Napoleon's brother-in law, Joachim Murat, commander-in-chief of the French army in Spain. Resistance to the French by regular Spanish forces under General Castanos and by irregular guerilla forces sprang up across Spain, and a French army under General Dupont was forced to surrender to Castanos at Bailen in July 1808. This capitulation was a significant blow to France's reputation for invincibility. Meanwhile a British army under Sir Arthur Wellesley landed in Portugal, and forced the French to evacuate that country (August 1808).

Napoleon rushed part of the Grande Armée to Spain, took personal command (November 1808), restored the ousted Joseph to the throne, defeated the Spanish forces and drove the British out of Portugal. Wellesley's successor, Sir John Moore, was killed at La Coruna, but his army was safely evacuated by sea, while Portugal and southern Spain remained unsubdued. Napoleon returned to Paris to deal with the threat from Austria, leaving the Spanish question unresolved.

By January 1809 France's casualties in the Peninsular War exceeded her losses in all of Napoleon's campaigns in Europe hitherto. British forces returned to the peninsula in 1809. 50,000 British troops and their Portuguese and Spanish allies under Wellesley (now Duke of Wellington) ultimately tied down between 200,000 and 300,000 French troops. French depredations, guerilla reprisals and French counter-reprisals made the occupation of Spain a uniquely long drawn out, sanguinary and costly ordeal marked by atrocities on both sides. By 1814 the French forces had suffered in battle and through guerilla attrition losses totalling 240,000 men, as well as huge financial strains. The French were gradually driven out of Spain in the campaigns of 1812–1814, which culminated in Wellington's invasion of southwest France. The ‘Spanish ulcer’ and Peninsular War were a major contribution to Napoleon's defeat.

In 1814 the Bourbon monarchy in Spain was restored to power in the person of Ferdinand VII, who ruled until 1833. During Ferdinand's exile in France an attempt had been made in 1812, by the exiled Spanish parliament, to formulate a liberal constitution for Spain. Ferdinand suppressed such measures in order to reinstate a particularly autocratic form of absolutism. Viewed by many as Spain's saviour from the Antichrist Napoleon, he was quick to purge his country of supporters both of the liberal constitution and of the French regime. In 1814 he reinstated the powers of the Inquisition, previously abolished by Joseph Bonaparte. Although the Inquisition's use of torture and the death penalty had declined in the eighteenth century and its main focus had become issues of censorship, it retained in the minds of liberals the kind of cruel and repressive associations present in popular images, including those of Goya. To supporters of the Bourbon restoration, however, the Inquisition functioned as a symbol of Spain's attempt to cleanse itself of foreign, libertine and Francophile influence.

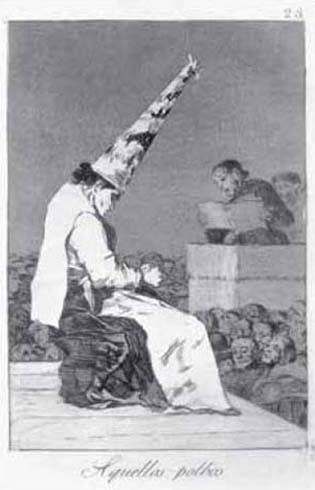

Figure 2

Figure 3

2 The work of Goya

Goya developed from a decorator of churches to a court artist, accomplished portraitist, satirical graphic artist and a painter of dark, nightmare visions. His work at court, for Carlos III and Carlos IV, involved both decorative work and a series of portraits of key figures who moved in court circles. As his official, public work became more sought after, however, he developed a parallel career as a graphic artist that seemed to express more freely a private view of the injustices, vices, follies and inhumanity of contemporary society. This shift coincided with his own increasing deafness. It also intensified as Spain was wracked by the grief and suffering of war provoked by the Napoleonic invasion. Some of the art that emerged from the Peninsular War and its aftermath suggested a shift of interest away from Enlightenment reform and towards more troubled, private fantasies and preoccupations. And yet the public at large perhaps was not ready for this. Although Goya's first major engraved series, Los Caprichos, went briefly on sale before being withdrawn, his later series, Disasters of War, was not published during his lifetime.

Exercise 1

Click on the links below and view the video. The video is supplied in three sections, and you should watch them in the order they appear below. As you do so, think about the following questions. Don't read the discussion until you have finished.

How is the influence of the Enlightenment evident in Goya's early career?

How were the effects of the Napoleonic invasion reflected in his art?

In what ways did Goya's art move towards a Romantic concern with the darker forces of unreason, mystery and suffering?

Click below to view part 1 of the video.

Transcript: Part 1

Click below to view part 2 of the video.

Transcript: Part 2

Click below to view part 3 of the video.

Transcript: Part 3

Discussion

After beginning to work at the Spanish court Goya painted the portraits of many of Spain's leading Enlightenment figures. Madrid was at the time a centre of enlightened developments in science, astronomy and the arts. Although we cannot infer from this any clear allegiance by Goya to the ideals of the Enlightenment, he did frequent a milieu receptive to Enlightenment ideas, even if these ideas were not yet widespread in Spain as a whole. You may have noticed that they were largely restricted to court circles and to the ruling intelligentsia. His advertisement for the print series, Los Caprichos, also betrayed some sharing of the Enlightenment's aim to correct folly, injustice and vice. (You may also be interested to know that Godoy commissioned from Goya a series of allegorical paintings on the Enlightenment themes of science, industry, agriculture and commerce, thus suggesting his own Enlightenment credentials.)

In the Second of May 1808, the Third of May 1808 and the engraved series, Disasters of War, the Napoleonic invasion is seen as an act of violent oppression that acted as a spur to patriotic fervour, heroism and courage. War is seen primarily as a crime against humanity.

The Disasters of War and the so-called Black Paintings are among the later works of Goya that suggest indefinable, mysterious or irrational subjects and a unique, original artistic vision. War is seen mainly as an indiscriminate creator of victims and suffering. Goya's view on the Academy rebels against the tyranny of rules, and it might be argued that there is a parallel between the unleashing of the irrational forces of war and developments in his artistic outlook. There had, of course, been signs of the grotesque and the irrational in earlier works such as Los Caprichos. But there the grotesque, the superstitious and the unjust had been contained within an essentially moralising and satirical framework. In the later works the reforming powers of reason seem absent or irrelevant, and the balance between empirical observation and fantasy seems to shift towards the latter. The light of reason gives way to the dark recesses of the imagination.

In his 1792 address to the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Goya had stressed the importance to artists of studying nature, as opposed to the uninformed, servile copying of Greek statues or the following of rules proposed by those who have written about art:

It is impossible to express the pain that it causes me to see the flow of the perhaps licentious or eloquent pen (that so attracts the uninitiated) and fall into the weakness of not knowing in depth the material of which he writes; What a scandal to hear nature deprecated in comparison to Greek statues by one who knows neither the one, nor the other, without acknowledging that the smallest part of Nature confounds and amazes those who know most! What statue, or cast of it might there be, that is not copied from Divine Nature? As excellent as the artist may be who copied it, can he not but proclaim that placed at its side, one is the work of God, the other of our miserable hands? He who wishes to distance himself, to correct it [nature] without seeking the best of it, can he help but fall into a reprehensible and monotonous manner, of paintings, of plaster models, as has happened to all who have done this exactly?

(Quoted in Tomlinson, 1994, p. 306)

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Observation of nature, in the form of his contemporaries and their lives, certainly nourished Goya's own art. Increasingly, however, he engaged in a liberated form of artistry in which imitation became subservient to creativity: this was one of the key shifts inherent in the move from Enlightenment to Romanticism. His etching from the Los Caprichos series, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (Plate V2.1) encapsulates this shift as a contest of truth and imagination. When first drawn and etched in 1797, this was envisaged as a frontispiece and was accompanied by the caption: ‘The Author Dreaming. His only intention is to banish those prejudicial vulgarities and to perpetuate with this work of caprichos the sound testimony of truth.’ Creatures of the night represent those ‘prejudices’. We see owls and bats (which then represented ignorance and the forces of darkness) and a lynx, emblem of the power of sight. It is an ‘ignorant’ owl that prompts the artist into action. The total effect is one of ambiguity. Will darkness predominate in the artist's mind, or will his vigilance and alertness help to expose and banish these creatures of the night, as befitted the satirical intention of the series?

Click to view Plate V2.1 The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.

3 Chronology

| Timeline | Event |

|---|---|

| 1746 | (30 March) Goya born in Fuendetodos, in the province of Aragon. |

| 1759 | Carlos III of Spain ascends the throne. |

| 1760 | Goya apprenticed to the painter José Luzán. |

| 1770–1 | Travels in Italy. |

| 1771 | First important commission, The Adoration of the Name of God, for the basilica of Santa Maria del Pilar, Saragossa. |

| 1774 | Summoned to Madrid to work at the royal tapestry factory at Santa Bárbara. |

| 1778 | (July) Publishes prints after paintings by Velázquez. (13 October) Pablo de Olavide trial. This land reformer was banished by the Inquisition to a monastery for eight years. One of his ‘crimes’ was a correspondence with Voltaire and Rousseau. |

| 1780 | (5 July) Goya elected to the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Madrid. His reception piece is Christ on the Cross. |

| 1782 | Carries out portrait commissions for important patrons associated with the Bank of San Carlos. Many other important commissions follow in the 1790s and through the turn of the century. |

| 1785 | Becomes assistant director of painting at the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts. |

| 1786–7 | Along with Ramón Bayeu is named painter to King Carlos III and continues to produce tapestries for royal palaces. |

| 1788 | Carlos IV ascends the throne. |

| 1789 | Goya promoted to Court Painter of the royal palace of Aranjuez. |

| 1792 | Godoy is appointed prime (first) minister and is instructed to resume relations with France disrupted by the Revolution. |

| 1792 | (14 October) Goya sends letter to the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts on the teaching of painting. Later that year he contracts an infection that will lead to deafness. |

| 1793 | France declares war on Spain. |

| 1793–4 | Goya produces a series of cabinet pictures (a small picture open to close, leisurely scrutiny and often displayed in private spaces as a valuable personal possession) for Bernardo de Iriarte, vice-protector of the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts. He says, ‘I have realized observations that are usually not permitted by commissioned works, and in which caprice and invention have no greater extension’ (from a letter to Iriarte, quoted in Tomlinson, 1994, p. 94). These paintings include his Courtyard with Lunatics and Strolling Players. |

| 1795 | Godoy signs peace treaty with France and Carlos IV names him ‘the Prince of Peace’. |

| 1795 | (September) Goya named director of painting at the Academy. |

| 1796 | (August) France and Spain sign offensive and defensive alliance against Britain, and Spain declares war on Britain. |

| 1797 | Goya resigns directorship at the Academy due to ill health. |

| 1797 | (November) Godoy forms new government including reformists such as Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos and Meléndez Valdés. |

| 1798 | Goya is now dependent on sign language as a means of communication. |

| 1799 | Goya's Los Caprichos, based on drawings made in the preceding two years, are published. They are placed on sale in a perfume shop but quickly withdrawn. This has given rise to subsequent speculation about the commercial viability of the prints in a market more accustomed to portraits, religious prints and prints showing recent events, but some of the subjects it treated (for example, witchcraft) were certainly fashionable (Tomlinson, 1994, p. 143). |

| 1799 | (31 October) Goya appointed Primer Pintor de Cámara (First Court Painter). |

| 1800–1 | Portrait of Family of Carlos IV (Plate V2.2) completed and Goya paints Godoy to celebrate his recent victory over Portugal (Plate V2.3). |

| 1802 | In a bid for peace with Britain Napoleon cedes Spanish territory of Trinidad to the British without telling Spain. |

| 1803 | Napoleon involves Spain in war with Britain. |

| 1804 | Napoleon declares himself Emperor of France. |

| 1805 | (21 October) French and Spanish fleets defeated at Trafalgar. |

| 1806 | Napoleon declares Continental Blockade against Britain. |

| 1807 | French troops enter Spain. Godoy discovers that Ferdinand, son of Carlos IV, has entered into secret talks with Napoleon's entourage. He denounces Ferdinand, who is arrested and later pardoned. |

| 1808 | (March) Carlos IV abdicates in favour of Ferdinand after rumours that Godoy is poised to capitulate to the French. The following month Napoleon lures the Spanish royal family to Bayonne and induces them to abdicate in favour of Joseph Bonaparte. |

| 1808 | (2 May) Beginning of War of Independence (Peninsular War) in Spain and of massive revolt against Napoleonic occupation. |

| 1808 | (3 May) French troops take reprisals against uprisings in executions at the Príncipe Pío, Madrid. |

| 1808 | (June) Napoleon places his brother Joseph on Spanish throne. Carlos IV and Maria Luísa are exiled and Ferdinand is placed under house arrest at Valencay. He is later declared by provincial juntas to have legitimate claim to the throne. Goya completes an equestrian portrait of him. Later that year Cádiz becomes the centre of liberal opposition to the French. |

| 1809 | Fall of Saragossa, which had been under siege by French troops for several months. |

| 1810–14 | Goya works on first plates in the Disasters of War series. |

| 1810 | Goya produces for the city of Madrid an allegorical painting of the city gesturing towards King Joseph I of Spain. He later alters this painting as the political situation changes. |

| 1810 | (December) The Inquisition is suppressed and work begins by the parliament or Cortés based in Cádiz on a new, liberal constitution for Spain. |

| 1811 | Joseph confers royal honours on Goya which the artist subsequently plays down. |

| 1812 | Constitution of Cádiz is adopted by the Cortés, limiting royal powers and those of the feudal nobility. |

| 1812 | (August) Arthur Wellesley enters Madrid after defeating the French. Goya draws his portrait. The French subsequently regain Madrid. |

| 1813 | Office of the Inquisition abolished by the Cortés. In June Wellesley (now Duke of Wellington) defeats the French at Victoria. Joseph I flees Spain. Ferdinand VII is released by Napoleon and signs alliance with France against Britain. |

| 1814 | After a regency council is established in Madrid, Goya declares his wish to ‘perpetuate by means of the brush the most notable and heroic actions and scenes of our glorious insurrection against the tyrant of Europe’ (quoted in Tomlinson, 1994, p. 181) and paints the Second of May 1808 and the Third of May 1808 (Plates V2.5 and V2.6). |

| 1814 | (April) Napoleon abdicates. Ferdinand VII later revokes the new constitution and reinstates the Inquisition. He establishes himself as an absolute ruler by divine right. Goya retains his court salary, pension and civil rights. However, the Baroque style of Vicente López (see Plate V2.4) seems to have found greater favour with the new king than Goya's more loosely painted and informal portrait style which, while highlighting the colours and textures of the royal costume (Plate V2.7), placed less emphasis on the trappings and swaggering pose of the monarch. Goya would also find himself out of step with Ferdinand's later preference for the neoclassical. |

| 1816–17 | Goya etches the Disparates (Follies) series, not published until after his death. |

| 1816 | Goya publishes etchings on bull fighting subjects. At the same time he produces works such as the Madhouse (Plate V2.8) satirising religion and authority, symbolised by the inmates' crowns and sceptres. In ‘private’ works such as this he was free to choose his subjects and could escape the confines of public commissions. |

| 1819 | Goya moves to the Quinta del Sordo and a year later begins work on the so-called Black Paintings. |

| 1820–3 | He works on later plates from the Disasters of War series. |

| 1820 | Ferdinand VII is forced to become a constitutional monarch after a revolution. Goya later swears allegiance to the constitution and monarch. |

| 1823 | The French under Louis XVIII invade Spain and restore Ferdinand to absolute power. Ferdinand instigates a reign of terror as he punishes liberals. |

| 1824 | After going into hiding Goya witnesses an amnesty for liberals and asks leave, on grounds of health, to live in France. Ferdinand grants this. Goya visits Paris and probably the Salon, at which works by Delacroix, Ingres and Constable are exhibited. He then moves to Bordeaux where he lives for the rest of his life, although he visits Madrid in 1826 and 1827, partly to secure an annual pension from the king. |

| 1828 | (16 April) Goya dies in Bordeaux. In 1901 his remains are transferred to Madrid, but it is discovered that his head is missing. In 1929 they are transferred to their current resting place, the church of San Antonio de la Florida, Madrid. |

Figure 7

4 Illustrations shown on the video in order of their appearance

4.1 Works by Goya

Third of May, 1808, 1814, oil on canvas, 268 x 347 cm, Prado, Madrid (Plate V2.5).

Second of May, 1808, 1814, oil on canvas, 268 x 347 cm, Prado, Madrid (Plate V2.6).

The Adoration of the Name of God, 1772, fresco, 700 x 1500 cm (approx.), Basilica de Santa María del Pilar, Saragossa.

The Meadow of San Isidro, 1788, 419 x 908 cm, Prado, Madrid.

Self-Portrait, c. 1781–2 (or c.1785: date contested), oil on canvas, 42 x 28 cm, San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Madrid.

Carlos IV in Hunting Costume, 1799, 209 x 129cm, Royal Palace, Madrid.

Queen Maria Luisa in a Mantilla, 1799, 208 x 130cm, Royal Palace, Madrid.

Juan de Villanueva, c. 1800–5, 90 x 67 cm, Royal Academy of San Fernando, Madrid. (Villanueva was architect of the Prado and of the Royal Observatory, Madrid. He was made director of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and wears the uniform of this office in the portrait.)

J.A. [Juan Antonio] Meléndez Valdés, 1797, oil on canvas, 733 x 571 cm, Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle. (Valdés was a poet and Francophile. He had to go into exile in France after Ferdinand VII's return to the throne.)

Sebastián Martínez, 1792, oil on canvas, 92.9 x 67.6 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. (Martínez was a businessman and art collector. He was also general treasurer of the Finance Board of Cádiz and became a member of the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1796. Goya stayed with Martínez in 1792 prior to his illness.)

Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, 1798, oil on canvas, 205 x 133 cm, Prado, Madrid. (Jovellanos was a politician and writer who was made minister of the interior in 1797, when Godoy made attempts to liberalise the Spanish government.)

‘The Tyrant’: Portrait of Actress María del Rosario Fernández, c.1792, 206 x 130 cm, oil on canvas, San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Madrid.

Family of the Infante Don Luis, 1784, 248 x 340 cm, oil on canvas, Magnani Foundation, Parma.

Family of the Duke and Duchess of Osuna, 1788, 255 x 174 cm, oil on canvas, Prado, Madrid.

The Kite, 1778, 269 x 285 cm, oil on canvas (tapestry cartoon), Prado, Madrid; corresponding tapestry at Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial.

The Count of Altamira, 1786–7, oil on canvas, 177 x 108 cm, Banco de Espana, Madrid. (The count was a member of the Board of the Banco de San Carlos and in 1796 a member of the Academy of San Fernando.)

The Count of Floridablanca, 1783, oil on canvas, 260 x 166 cm, Banco de Espana, Madrid. (The Count of Floridablanca was one of the driving forces behind enlightened absolutism in Spain. He instigated many enlightened projects, including botanical gardens, the Royal Observatory, the Banco de San Carlos, bridges, highways and canals.)

Godoy as Commander in the War of the Oranges, c.1801, 180 x 267 cm, oil on canvas, San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Madrid (Plate V2.3).

Strolling Players, 1793, 42.5 x 31.7 cm, oil on tinplate, Prado, Madrid.

Yard with Lunatics, 1793–4, 43.8 x 32.7 cm, oil on tinplate, Meadows Museum, Dallas, Texas.

From Los Caprichos:

Note: the etchings in the film from Los Caprichos and from Disasters of War are from the Ceán Bermúdez albums at the British Museum. These albums contain Goya's working proofs with manuscript titles in his own hand. Titles and captions were often changed in later versions of the prints. This, together with the variants produced by different translators, means that there are today a number of recorded titles for each print.

In Los Caprichos Goya experimented with the relatively recent technique of aquatint. This involved covering some parts of the metal plate used to produce the print with a porous resin, while ‘stopping out’ other parts (that is, preventing them from absorbing ink) by covering them with varnish. The stopped-out sections would finally appear white while the resin-covered section would absorb ink through tiny ‘holes’ between the grains of resin. In this way and through subsequent ‘bitings’ of the plate in an acid bath, soft, velvety and granular shaded areas would be produced. Thus, Goya was able to enhance the effects of etched lines (or drawing) through the addition of varied and expressive tonal effects. Half-tones could be created through the process of burnishing, in which a special tool is used to make flatter or smoothed-down areas of the plate which carry less ink than they would have done and hence produce lighter areas on the finished print.

They Say Yes and Give Their Hand to the First Comer, Plate 2 of Los Caprichos print series, 1797–8, etching with aquatint.

Nanny's Boy, Plate 4 of Los Caprichos print series, 1797–8, etching with aquatint.

And So Was his Grandfather, Plate 39 of Los Caprichos print series, 1797–8, etching with aquatint (also called As Far Back as his Grandfather) (Figure 7).

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, Plate 43 of Los Caprichos print series, 1797–8, etching with aquatint (Plate V2.1).

Self-Portrait, 1782, oil on canvas, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Agen, France.

Family of Carlos IV, 1800–1, 280 x 336 cm, Prado, Madrid (Plate V2.2).

From Disasters of War, 1810–1814:

Gloomy Presentiments of Things to Come.

Whether Right or Wrong.

Women Give Courage.

And They Are Like Wild Beasts.

What Courage! (Figure 5).

This is Worse.

Charity (Figure 4).

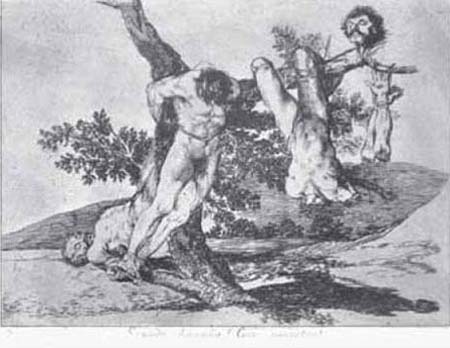

What a Feat! With Dead Men! (also called A Heroic Feat! With Dead Men!) (Figure 6).

Self-Portrait with Doctor Arrieta, 1820, 117 x 79 cm, oil on canvas, Institute of Arts, Minneapolis.

Nobody Knows Himself, Plate 6 of the Los Caprichos print series, 1797–8.

That Certainly is Being Able to Read (or He Certainly Can Read), Plate 29 of the Los Caprichos print series, 1797–8.

There is Plenty to Suck, Plate 45 of the Los Caprichos print series, 1797–8.

The garden front of the Quinta del Sordo; woodcut from Charles Yriate's Goya book of 1867 (engraving).

The garden front of Goya's house; photograph by Asenjo. Published in La Illustración Española Americana, 1909. At the time of writing (May 2003) it has been suggested by one of Goya's biographers that the so-called Black Paintings were works not of Goya but of his son. This remains an open question for subsequent investigation.

‘Black Paintings’

Duel with Clubs, 1820–3, plate negative of Black Painting in original location made by J. Laurent, c. 1863–6. The original plate is now in the Archivo Ruiz Vernacci, Madrid, at the Centro de Informatión y Documentatión del Patrimonio Artístico, Madrid.

The Three Fates, as above.

A Procession of the Holy Office (also called Pilgrimage to San Isidro Fountain), as above.

Asmodeus (also called Witches Sabbath), as above.

The Dog, as above.

Ferdinand VII, c.1783, Prado, Madrid.

4.2 Works by other artists

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Bonaparte as First Consul, 1804, 227 x 147 cm, Musée d'Art Moderne et d'Art Contemporain de la Ville de Liège (Plate 9.12).

Michel-Ange Houasse, The Drawing Academy, c.1725, 61 x 72.5 cm, oil on canvas, Royal Palace, Madrid (Unit 1, Figure 1.8).

Diego de Velásquez, Las Meninas, 1656, 318 x 276 cm, oil on canvas, Prado, Madrid.

After José Aparicio, Glories of Spain, engraving, after a painting of 1815–18, now lost, Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid (Figure 2).

Conclusion

This free course provided an introduction to studying the arts and humanities. It took you through a series of exercises designed to develop your approach to study and learning at a distance and helped to improve your confidence as an independent learner.

References

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Dr Linda Walsh.

This free course is an adapted extract from the course A207 From Enlightenment to Romanticism c.1780-1830, which is currently out of presentation

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Licence

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Course image: Goya in Wikimedia available in the public domain.

Figure 1 Francisco de Goya, "Self Portrait", Plate 1 of "Los Caprichos" print series, 1799, etching, 22 x 15.3 cm, private collection. Photo: Bridgeman Art Library

Figure 2 After José Aparicio, "The Glories of Spain", engraving, after painting 1815-18, now lost, Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid. Photo: Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid.

Figure 3 Francisco de Goya, "Those Specks of Dust", plate 23 of "Los Caprichos" series, 1799, etching with aquatint, 21.9 x 15cm, private collection. Photo: Index/ Bridgeman Art Library

Figure 4 Francisco de Goya, "Charity", Plate 27 of "Disasters of War" series, 1810-14, etching, 16.3 x 23.6 cm, private collection. Photo: Index/Bridgeman Art Library

Figure 5 Francisco de Goya, "What Courage!", Plate 7 of "Disasters of War" series, 1810-14, etching, private collection. Photo: Inex/ Bridgeman Art Library

Figure 6 Francisco de Goya, "A Heroic Feat! With Dead Men!", Plate 39 of "Disasters of War" series, 1810-14, etching, 15.6 x 20.8 cm, private collection. Photo: Index/Bridgeman Art Library

Figure 7 Francisco de Goya, "As Far Back as his Grandfather", Plate 39 of "Los Caprichos" print series, 1799, etching with aquatint, 21.8 x 15.4 cm, private collection. Photo: Index/Bridgeman Art Library

Plate V2.1 Francisco de Goya, 'The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters', c.1798, etching with aquatint, 21.6 x 15.2 cm, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lille. Photo: © RMN/ Quecq d'Henripret

Francisco de Goya, "A Heroic Feat! With Dead Men!", Plate 39 of "Disasters of War" series, 1810-14, etching, 15.6 x 20.8 cm, private collection. Photo: Index/Bridgeman Art Library

Every effort has been made to trace all the copyright owners, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity

1. Join the 200,000 students currently studying withThe Open University.

2. Enjoyed this? Browse through our host of free course materials on LearningSpace.

3. Or browse more topics on OpenLearn.

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University