Wilberforce

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 20 April 2024, 5:36 PM

Wilberforce

Introduction

William Wilberforce, the politician and religious writer, was instrumental in the abolition of slavery in Britain. This course explores Wilberforce’s career and writings and assesses their historical significance. In particular it examines the contribution that Evangelicalism, the religious tradition to which Wilberforce belonged, made in the transitions between the Enlightenment and Romanticism. Throughout it relates Wilberforce’s career and writings to wider social and cultural developments in Britain, with special regard for British reaction to the French Revolution.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 2 study in Arts and Humanities.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand the key aspects of William Wilberforce’s political career and writings, and have an appreciation of their historical and religious significance

demonstrate an awareness of the relationship of Evangelicalism to cultural transitions between the Enlightenment and Romanticism

understand the contribution of religion to cultural, social and political change in Britain in the years after the French Revolution.

1 Wilberforce’s early career

1.1 Early influences

In the early summer of 1771, the clergyman and writer John Newton (1725–1807) was visited at Olney by two of his admirers, William and Hannah Wilberforce, a wealthy childless couple, and their 11-year-old nephew and heir, also named William. Newton made a profound impression on the boy. In 1785 it was to Newton that the younger William Wilberforce (1759–1833), now Member of Parliament for Yorkshire and a close friend of Prime Minister William Pitt (the Younger), turned for counsel in the midst of a period of spiritual crisis. Wilberforce’s commitment to Evangelicalism was to be a defining feature of a remarkable political career, the most notable feature of which was his long campaign for British abolition of the slave trade. Wilberforce was also concerned with spiritual and moral conditions at home, expressed in his book A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians… Contrasted with Real Christianity (1797) which was very popular and influential at the time. Reading and understanding parts of this text and some of his writings on slavery form the substance of this course. The study of Wilberforce provides insights not only into the interactions between the Evangelical movement and its wider social and political environment, but also into the impact of the French Revolution on Britain and into British relations with the non-European world, as focused by the campaign against slavery.

1.2 Upbringing; MP for Yorkshire

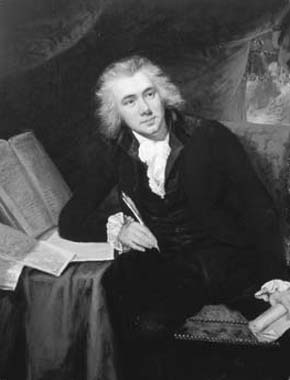

William Wilberforce (Figure 1) was born in Hull, the son and grandson of substantial merchants who had made their fortune in trade between Yorkshire and the Baltic. His father died in 1768 and he subsequently went to live for a period with his uncle and aunt. Through them he was exposed not only to the influence of John Newton, but also to that of George Whitefield (1714–70), one of the major leaders of early Evangelicalism and of the Methodist movement. His mother sought to steer him towards a more conventional Christianity, and appeared successful in the short term. William graduated from Cambridge in 1780 as a sociable and ambitious young man, morally upright by the standards of the day, but without any signs of intense religious commitment. He had already decided that his future lay in politics rather than in the family business, and almost as soon as he was of age he was elected MP for Hull, in September 1780. In 1784 he became MP for the county of Yorkshire, an immense and populous constituency, which gave him an important power base.

Figure 1

Wilberforce came into Parliament at a time of considerable political turmoil. Eighteenth-century affiliations were fluid in comparison to the modern party system. The labels ‘Whig’ and ‘Tory’ had first emerged in the religious and constitutional conflicts of the late seventeenth century, but had changed their meaning during the course of the following century. Since the accession of George III in 1760 the Tories, who had been in the political wilderness for decades, had enjoyed a recovery, being favoured by the king, who saw them as a means to assert his own influence against the aristocratic Whig cliques who had previously dominated Parliament. In the early 1780s, however, the Whigs regained ground, benefiting politically from concern about a perceived growth in royal influence and military defeat in the War of American Independence (1775–83) for which the Tory government of Lord North was held responsible. The Whigs were, though, seriously weakened by their own factionalism, which made it impossible for them to form a stable administration after North's government fell in March 1782. Following two turbulent years the king appointed as prime minister the 24-year-old William Pitt, hitherto identified with the Whigs and supportive of reforms that would remove obvious corruptions and abuses, but willing to uphold the continued constitutional influence of the monarchy. Hence he came to be perceived as a Tory. Pitt was to remain prime minister until his death in 1806, apart from a short gap between 1801 and 1804. Wilberforce was a close friend of Pitt’s and his political position was a similarly broadly conservative one, committed to the essentials of the existing social order and constitutional structure, but keen to promote moderate reforms.

1.3 Wilberforce’s ‘Conversion’ to Evangelicalism

Wilberforce’s religious ‘conversion’ in 1785 was profound but not instantaneous. Through the influence of Isaac Milner, an Evangelical clergyman who was his companion on extended journeys on the Continent, he first became intellectually convinced of the truth of Christian doctrines that he had doubted in the early 1780s. This process of rational argument, study and consideration was characteristic of an Enlightenment way of thinking, even if the conclusion was diametrically opposed to that of sceptical Enlightenment philosophers such as David Hume (1711–70). Then, in November 1785, Wilberforce had an intense spiritual experience, making him feel that his own past life was futile, that he was utterly dependent on the infinite love of Christ, and that his future life must be committed to the service of God. It was in trying to come to terms with these new convictions that he recalled his boyhood acquaintance with Newton, now rector of St Mary Woolnoth in the City of London, and turned to him for advice. Newton, evidently perceiving in Wilberforce a recruit to Evangelicalism of great potential influence, counteracted his impulse to withdraw into primarily spiritual concerns, and strongly counselled him to remain in politics. This advice was heeded. Moreover, although Wilberforce’s new-found convictions gave him a strong strain of zealous earnestness that ran through his writings and speeches, he remained on the surface an easy-going, extrovert and likeable person, who could inspire considerable affection even from those who disagreed with him. He also remained a shrewd ‘political animal’ whose strong commitment to long-term visions and objectives did not prevent considerable flexibility in short-term tactics. Herein lay key reasons for his success in pursuing sometimes unpopular causes.

Wilberforce’s conversion confirmed an inclination to follow an independent parliamentary career rather than to accept the constraints that would have come from seeking and holding government office. He was assisted in this respect by considerable personal wealth that freed him from any financial necessity for holding a salaried post. During 1787 the two pre-eminent concerns of the rest of his career became clear. First, he emerged as the parliamentary leader of the growing campaign for the abolition of the slave trade, complementing the activities of those who sought to stir up popular sentiment against slavery, including Thomas Clarkson (1760–1846), who became the driving force behind the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade and published a classic account of the movement in 1808. Second, he began purposefully to promote moral and spiritual reform at home, initially through obtaining the issue of a royal proclamation ‘for the Encouragement of Piety and Virtue’.

1.4 Wilberforce in Parliament

When Wilberforce made his first major speech against the slave trade in the House of Commons in April 1789, few could have anticipated that it was the start of a campaign that he would have doggedly to maintain for 18 years. During most of the period between 1789 and 1807 Wilberforce brought forward at least one anti-slave trade motion or measure every year, to be met often with defeat, sometimes with partial successes that could not be translated into effective legislation. His initial timing was unfortunate because the outbreak of the French Revolution only a few months later stirred over the next few years a growing sense of insecurity in the British political elite. War with France followed in 1793. This meant that the abolition of the slave trade was liable to be regarded with enhanced suspicion because of the potential for unforeseeable consequences, notably in relation to the economics of overseas trade and British strategic interests in the West Indies.

It was in the early years of the Revolutionary Wars that Wilberforce, currently stalemated in his campaign against the slave trade and increasingly concerned about the condition of society at home, began work on the Practical View. Before looking more closely at this text, however, we set the scene with reference to the state of British religion, politics and society in the aftermath of the French Revolution.

2 Britain and the French Revolution

In Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) Edmund Burke (1729–97) made clear his hostile reaction to the Revolution, which he perceived as a dangerous destruction of tradition and continuity in favour of abstract Enlightenment principles. On the other hand, there was a substantial cross-section of British opinion that initially warmly welcomed the Revolution, including Wilberforce himself, as well as much more radical individuals, such as Thomas Paine (1737–1809).

Initially, the revolutionaries in France did not appear hostile to religion in general, although from an early stage the rationalist and Enlightenment ethos of the Revolution was reflected in quite radical reform of the Roman Catholic Church. From July 1790 the imposition of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy gave rise to a growing divide between the revolutionary government and the Church. Then in 1793 and 1794 there was an outright assault on traditional Catholic belief and the attempt to establish the cult of the Supreme Being in its place. This proved to be a temporary phase, but the enduring legacy of the Revolution in France was freedom of religion, in which non-Catholics enjoyed civil equality, and the ending of the privileged status of the Roman Catholic Church as an ‘estate’ of the realm.

From the point of view of the established churches in Britain the spectacle of the growing revolutionary onslaught on the French Roman Catholic Church was a double-sided one. For Protestants there were initially few regrets at the prospect of reforming what they believed to be false religion, but as it became clear that the preferred revolutionary alternative to Catholicism was not Protestantism but deism (the view that true religion is natural, not a matter of revelation), they became much more uneasy. At the same time the constitutional adoption of the principle of freedom in religion in France gave a boost to Dissenters from the Church of England, while heightening the insecurities of the supporters of the existing Church establishment.

The initial British perception of the Revolution was of a moderate move away from corrupt absolute monarchy towards the kind of ‘balanced’ constitution on which the British elite prided itself. It was therefore welcomed by all but the most conservative. As, however, in the early 1790s more radical and violent elements gained ground in Paris, erstwhile British sympathisers tended to become much more uneasy. Their fears were confirmed by the execution of Louis XVI in January 1793, and after the outbreak of war in the following month the French and above all the supporters of the Revolution tended to be demonised as enemies. Thereafter too the minority in Britain who continued to identify enthusiastically with the Revolution were liable to be labelled as subversives and traitors.

3 Britain in the 1790s

A problem that has exercised historians for many years is, put in its most concise form: why was there no revolution in Britain in the 1790s? The question is a significant one here, because religious factors have formed an important strand in the answers that have been given. The intellectual trend was set by the publication in 1913 of England in 1815, in which the French historian Elie Halévy (1870–1937) argued that the growth of Methodism in this period was a key factor in the British avoidance of revolution. Later scholars gave their attention not only to Methodism but also to the role of the wider Evangelical movement, including Wilberforce and Evangelicals within the Church of England (e.g. V. Kiernan, 1952, ‘Evangelicalism and the French Revolution’, Past and Present, pp. 44–56). In 1984 the view was again advanced that ‘evangelicalism… may, at least for some, have averted a potentially dangerous build-up of frustration and political discontent’ (I.R. Christie, 1984, Stress and Stability in Late Eighteenth-Century Britain: Reflections on the British Avoidance of Revolution, Oxford, Clarendon Press, pp. 213–14). The scholarly debate here is too complex and protracted to develop here. Nevertheless, some points are worth highlighting with respect to the discussion of Wilberforce’s writings.

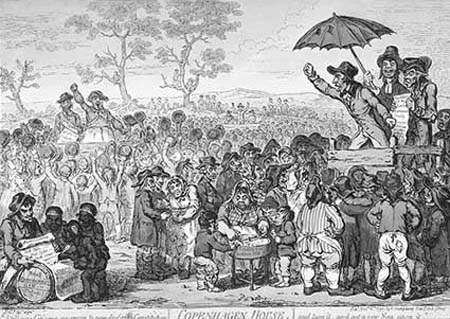

The 1790s were indeed a period of substantial social and political stress. At just the time the French Revolution broke out, the so-called ‘Industrial Revolution’ was gathering momentum, with associated rapid population growth, over-crowded and squalid living conditions, and reorganisation of traditional patterns of work and daily life. Supplies of food were sometimes erratic, giving rise to riots in 1795–6 and again in 1800–1. The outbreak of war led to substantial depression and unemployment because of the loss of export markets. Those in traditional industries such as handloom weaving, whose livelihoods were being threatened by the growth of new and more efficient technologies, experienced particular hardship. There were also significant ideological and organisational rallying points for those discontented with the existing order. Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man (1791) advocated the foundation of society on an Enlightenment conception of ‘natural rights’ rather than on the basis of historical patterns and precedents. Paine believed that such a vision was currently being realised in France. Radical Dissenters campaigned for civil equality with Anglicans. During the early 1790s there was a substantial movement of popular radical societies campaigning for political reform, centred on the London Corresponding Society (Figure 2) and, at its peak, having a presence in more than 80 English towns and cities. North of the border a General Convention of the Friends of the People in Scotland met in 1792. Apart from an extreme fringe, this was a movement for peaceful constitutional change rather than violent revolution.

It was also strongly and effectively opposed at a popular level by loyalist’ organisations that upheld the existing social and political structure. Nevertheless, conservatives were alarmed by the mere existence of popular radicalism, given the backdrop of revolution and war on the Continent and occasional instances of riot and unrest at home. Pitt’s government responded vigorously, prosecuting some radical leaders and in 1794 suspending habeas corpus, enabling them to hold suspected agitators without trial. In late 1795 it rushed through legislation extending the definition of treason to include any attempts to intimidate the government or Parliament, and banning ‘seditious’ meetings of more than 50 people. Wilberforce himself made a dramatic dash to York at the beginning of December 1795 to speak at a Yorkshire county meeting in defence of the government’s policy, arguing that it was not repression but a necessary safeguard of true balanced liberty.

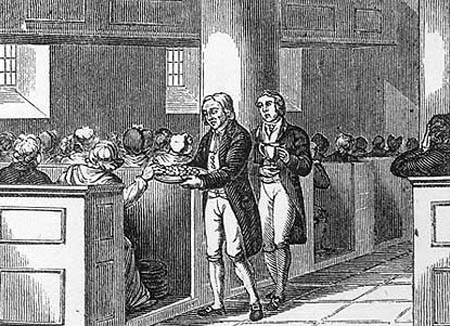

The 1790s also saw a rapid growth in Evangelicalism. Methodist membership increased from 56,605 in 1791 to 91,825 only a decade later. These figures almost certainly substantially understate the numbers of those influenced by Methodism by attending meetings, worship and preaching but not formally becoming members. Although there were some radical leanings within Methodism, as reflected in a split leading to the formation of the Methodist New Connexion in 1797, the great majority of the movement was conservative or at least apolitical (Figure 3). In his Making of the English Working Class (1963) E.P. Thompson emphasised the role of Methodism both in reconciling the poor to industrial work discipline and in deflecting them from revolution by turning their hopes for a better world towards the next life rather than this one.

A meeting of the radical London Corresponding Society in October 1795 is here vividly portrayed by the well-known caricaturist, James Gillray. Despite the movement’s wish to reshape the constitution, the impression given is more of good-natured protest than of revolutionary subversion.

Evangelicalism was also expanding elsewhere. The numbers of Baptists and Congregationalists (two of the main groups of Protestant Dissenters whose forbears left the Church of England in the seventeenth century), many of whom were influenced by the movement, grew by more than a third between 1790 and 1800. Although Evangelicals remained a small minority within the Church of England, they were nevertheless gaining ground. Wilberforce was one of a small but influential circle of prominent lay converts, who provided respectability and substantial financial resources. Moreover, even before the publication of A Practical View, a substantial Evangelical literary contribution was coming from the pen of Hannah More (1745–1833), a Bristol-based writer and teacher (Figure 4). Her Thoughts on the Importance of the Manners of the Great (1788) anticipated Wilberforce by criticising the elite for their failures of morality and social responsibility. In a series of tracts directed at the lower classes beginning with Village Politics (1792), she diffused an anti-revolutionary message extolling the virtues of a well-ordered society. These publications were very widely distributed during the 1790s.

By the early nineteenth century, Methodists – at least the more respectable and conservative Wesleyan Methodists – had generally moved away from the revivalist outdoor preaching of their early years and had built permanent chapels, which became a focus for community and social order. This engraving by an unknown artist depicts a Love Feast, or Holy Communion service, around 1820.

Figure 4

4 Wilberforce’s A Practical View

4.1 The impact of A Practical View

A Practical View is significant both as a kind of ‘manifesto’ by a prominent figure in a religious movement of rapidly expanding influence, and as part of an ongoing process of reflection on the state of British politics and society in the aftermath of the French Revolution. Wilberforce had been working on it intermittently for four years before its eventual publication on 12 April 1797. As a busy politician he struggled to find the time for sustained writing. He had initially had a pamphlet in mind, but the project grew in the making, and the book when it appeared was a substantial one of 491 pages. It has a somewhat rambling style: Wilberforce was prone to write as he talked, offering much eloquent rhetoric and lively insight, but he had neither the time nor the inclination for systematic and tightly structured thinking. Wilberforce’s underlying concern was to communicate what he believed to be the essential features of biblical Christianity to his contemporaries, first inspiring a commitment to ‘real Christianity’ in them, and thereby transforming the moral, political and social state of the nation. The work was an immediate success, selling 7,500 copies and being reprinted five times within six months of its publication. It went through nine English editions by 1811 and 18 by 1830. It was published in the United States in 1798, and translated into French in 1821 and Spanish in 1827.

In the opinion of Daniel Wilson, a prominent Evangelical clergyman in the next generation, ‘Never, perhaps, did any volume by a layman on a religious subject, produce a deeper or more sudden effect’ (‘Introduction to Wilberforce’s Practical View 1829, p. xvii). Its appeal was attributable in part to the prominence of its author, both as politician and as Evangelical leader, and in part to its offering of a vision for personal and national salvation at a time of considerable insecurity. In the spring of 1797 Britain found itself completely isolated in the war against France. Then, within a few days of the publication of A Practical View, a series of naval mutinies broke out in the fleets stationed in Spithead off Portsmouth and in the Thames estuary. In 1798 there was a rebellion in Ireland. These years were perceived by some at the time and since as a moment of real danger of revolution. In this context any book that offered a diagnosis of underlying national difficulties and a possible solution to them was likely to attract considerable interest.

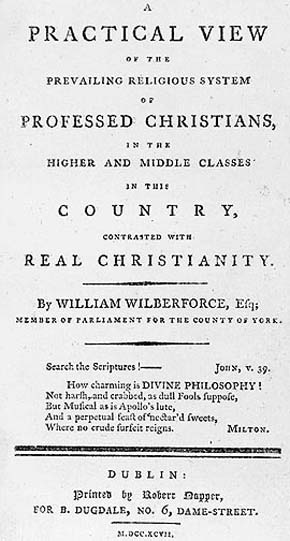

Title page of the 1797 Dublin first edition of William Wilberforce’s Practical View. The book was published almost simultaneously in both London and Dublin.

Click to view The Introduction to A Practical View

Exercise 1

Look at the illustration of the frontispiece, including the full cumbersome title (Figure 5), and read the Introduction to A Practical View in the attached pdf (above), then write answers to the following questions:

-

What image of himself do you think Wilberforce wanted to project through the book?

-

What further insights do you gain into his motives for writing it?

Discussion

-

Wilberforce is consciously trying to portray himself as both seriously concerned about religion and as an active public figure. His name and his position as ‘Member of Parliament for the County of York’ boldly appear on the title page. He is not sheltering behind the anonymity common among authors at this period, but deliberately using his own name, status and reputation as a means to arouse interest in the book. He is apologetic that ‘busyness’ deprives him of the opportunity for ‘undistracted and mature reflection’, but makes a virtue out of his lay status, which means that he cannot be accused of having a professional interest in promoting religion. His ‘view’ of the state of religion in the country is to be that of a ‘practical’ man, distinguished from the abstract theology written by the clergy.

-

The title immediately establishes Wilberforce’s central – and characteristically Evangelical – preoccupation with the dichotomy between ‘real’ and nominal Christianity. It also identifies his target as the ‘higher and middle classes’: while Wilberforce was worried about the spiritual and social state of the lower classes as well, he is not primarily concerned with them in this book. His overriding motivation is a spiritual one, calling his contemporaries to respond to the call of ‘real Christianity’ in this life before they have to face the judgement of Christ in the next. At the same time, though, he also believes religion to be ‘intimately connected with the temporal interests of society’, and accordingly that his work has an immediate relevance to the current political situation.

4.2 The ‘inadequate consciousness of the real teachings of Christianity’

Following the Introduction, Wilberforce describes what he regards as an inadequate consciousness of the real teachings of Christianity among those who profess to adhere to it. This ignorance is grounded in a widespread failure to study the Bible in any depth and detail. He then expounds the Evangelical view of human nature as fundamentally corrupt, evil and depraved, as against the ‘professed Christian’ view that it is ‘naturally pure and inclined to all virtue’. In this darkly pessimistic view of human nature, Wilberforce was also at variance with the relatively optimistic perception of humanity held by secular or deist Enlightenment writers. For him, such an insufficient awareness of sin leads to a failure to appreciate the central importance of the self-sacrifice of Jesus Christ in reconciling human beings to God and delivering them ‘from eternal misery’.

In an interesting digression Wilberforce comments on the role of emotions in religion, a passage that indicates the transitional nature of this text between Enlightenment and Romantic attitudes; that is, between the view that human nature is a constant: social, rational and progressive, and the view that it is driven by feelings, subjectivity and a strong sense of self. He observes that the ‘idea of our feelings being out of place in religion is an opinion which is very prevalent’, a view that he holds to be ‘pernicious’. Warm feelings, he argues, are very much expressed and advocated in the Bible, and, moreover, at a human level need to be cultivated and encouraged as a basis for worthwhile achievement. ‘Mere knowledge on its own’, Wilberforce maintains, ‘is not enough’. He therefore seems very much to be reflecting and encouraging one of the main cultural shifts of his time, that ‘from reason to sentiment and passion’. But in the very same passage he also shows his ties to the Enlightenment state of mind: he feels the need to justify his appeal to feelings as ‘reasonable’, on the grounds that it is supported by the authoritative text of Scripture and by the commonsense experience of life. And while the emotions need to be encouraged, they must also be controlled and tested in the objective examination of one’s daily life and achievements. Although it might at first seem difficult to cultivate warm feelings towards an invisible deity, in fact such emotions are ‘reasonable’ because they are encouraged by Scripture and apparent in the experience of Christians in past ages.

In the following lengthy chapter Wilberforce expands his comparison of a perceived widespread ‘inadequate’ understanding and practice of Christianity with his conception of ‘real’ Christianity. He addresses specific issues such as Sunday observance, advocating that the day should be ‘spent cheerfully’ on spiritual pursuits, helping others and spending uplifting time with family and friends. He denounces the contemporary practice of duelling as ‘the disgrace of a Christian society’. He criticises a tendency to equate Christianity merely with being considerate to others and leading a useful life. Such specific spiritual exhortations and moral critique of his contemporaries build up to his reiteration of what he believes to be the ‘grand radical defect in the practical system of these nominal Christians’ in the section entitled ‘Grand defect – neglect of the peculiar doctrines of Christianity’).

Click to view ‘Grand defect – neglect of the peculiar doctrines of Christianity’ from A Practical View

Exercise 2

Read ‘Grand defect – neglect of the peculiar doctrines of Christianity’ from A Practical View in the attached pdf (above) with the associated commentary, which will help you to understand this central pivot of Wilberforce’s argument and to appreciate its significance.

Discussion

Page 272

After the extensive preceding discussion of moral and lifestyle issues, Wilberforce now asserts the fundamental underlying importance of doctrinal issues. The three points he emphasises are the corruption of human nature, the atonement of the Saviour (Jesus) and the ‘sanctifying influence of the Holy Spirit’. First, Wilberforce claims, human nature is fundamentally flawed or, in theological terms, sinful. Sin comes not only from specific wrongdoing but from selfishness, neglect of doing good, and from a state of mind in rebellion against God. Sin is inherent to humanity (the doctrine of ‘original sin’), and dates back to Adam’s and Eve’s eating of the fruit of the forbidden tree in the Garden of Eden. This pessimistic view of human nature is clearly at variance with the more optimistic visions of human potential inherent in much Enlightenment thought, and nowhere more so than in the visionary schemes of the revolutionaries in France to create an ideal society. Second, ‘the atonement of the Saviour’ is shorthand for that sense of being ‘Wash’d in the Redeemer’s blood’ to be found in William Cowper’s (1731–1800) and John Newton’s Olney Hymns (1779) such as ‘Glorious things of thee are spoken’ (1:60) and ‘There is a fountain fill’d with blood’ (1:79). God’s justice means that he has to punish sinful humanity, but by dying on the Cross Jesus satisfies the need for judicial retribution. The ‘sanctifying influence of the Holy Spirit’ is not so much a feature of the Olney Hymns, but is nevertheless apparent in lines such as Cowper’s ‘Return, O holy Dove, return’ (1:3, verse 4). In traditional Christian teaching, following the resurrection of Jesus and his ascension into heaven, the Holy Spirit was a supernatural force poured out by God on his followers at Pentecost. It empowered them to continue to follow Jesus now that he was no longer physically present on earth, and to proclaim the Christian Gospel to others. For Wilberforce it is crucial to recognise the Holy Spirit's continuing presence today as a source of strength and power for holy and obedient Christian living, which is what he means by ‘sanctifying influence’. Here too, in emphasising the supernatural dimension of religion, Wilberforce is reflecting a wider cultural shift towards Romanticism.

Page 273

Before developing the assertions of the first two paragraphs directly, Wilberforce digresses to consider two kinds of religious resolution that he considers inadequate. First, bereavement or illness induces an awareness of mortality and leads someone to feel they have offended God. Hence they resolve to lead a more moral life in future. However, either they give up the attempt, or they set themselves too low a standard and become offensively complacent.

Pages 273–4

Second, there are those who really try hard, but become depressed by their own failures, being either driven to despair or to give up Christian belief altogether (‘infidelity’). Note Wilberforce’s implication that unbelief is a result of misconception and spiritual difficulty rather than an outcome of rational reflection.

Pages 274–6

The advice of conventional religious teachers that such strugglers should merely do their best and trust that all will be well is misleading comfort. Rather the Bible and, Wilberforce significantly adds, the official teaching of the Church of England itself require a much more radical approach. There needs to be heartfelt recognition of the goodness of Christ, leading to deep penitence and dependence on the grace of God for forgiveness. Holiness cannot be achieved by unaided human exertion, but requires first reconciliation to God through repentance and then the enabling power of the Holy Spirit.

Page 276

Failure to appreciate the above is the fundamental error of most nominal Christians. They need a much more profound sense of the depth of their own sinfulness, of the worth of the soul and of the costliness of Jesus’ self-sacrifice. Such recognition is the essential basis for true Christian morality.

4.3 Religion and political stability

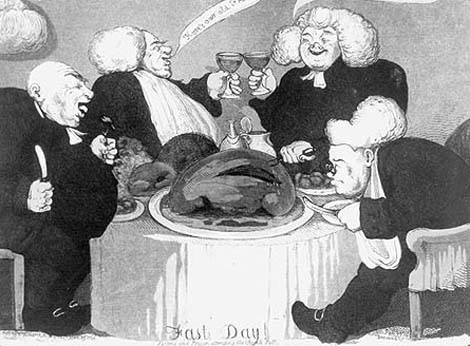

Wilberforce’s whole approach is strong indirect testimony to the predominance among his contemporaries of the kinds of religious outlook he is criticising, although objective evaluation requires a detachment from his own Evangelical zeal. Certainly his portrayal of the dominant tone of late eighteenth-century Christianity as one of undemanding endorsement of social harmony, decency and good neighbourliness rings true. A leading theological influence was that of William Paley (1743–1805) who, in his View of the Evidences of Christianity (1794), argued that the initial revelation of Christianity in the New Testament was associated with exceptional miraculous divine interventions in the natural order. These, however, did not recur in later ages or at the present time. It followed that contemporary Christianity would be orderly and predictable. Paley was also in tune with Enlightenment thought in emphasising the benevolence of God rather than divine judgement, and his scheme of belief had little place for the original sin that was fundamental to that of Wilberforce and the Evangelicals. Such theology gave rise to the approach of the ‘modern Religionists’ whom Wilberforce disliked. It was reflected in the easygoing religion evoked, for example, in the novels of Jane Austen, where clergy are portrayed as endorsing and conforming to the mores of the secular gentry (Figure 6). Nevertheless, Wilberforce was unduly dismissive of the piety of some of his Anglican contemporaries: there were indications of devotion and commitment in the late eighteenth-century Church of England that owed little to the Evangelical movement. Also, Methodism was growing strongly, although primarily among the lower classes who were outside the immediate scope of Wilberforce’s book.

This 1793 engraving by Richard Newton parodies the self-indulgence of the Church of England clergy, who are portrayed tucking into a lavish dinner when they are supposed to be fasting. Obviously a caricature, it points up the worldliness that Wilberforce was striving to counteract.

The cultural and political climate of the 1790s provided receptive soil for Wilberforce’s message. By 1797 even erstwhile enthusiasts for revolution would have had ample opportunity in the light of unfolding events in France to reflect on the extent of human ‘corruption’. While Wilberforce’s emphasis was thus a reiteration of a longstanding strand in Christian tradition, it also reflected the mood of the times, and a growing Romantic consciousness of the anarchic and violent potentialities of humanity. There was an increasing number of religious thinkers who took a more radical approach than Wilberforce did, believing that the current disordered state of the world presaged the apocalypse and the Second Coming of Christ. Such ideas were apparent in the visionary poetry and paintings of William Blake and in the preaching of popular prophets such as Joanna Southcott, who claimed prophetic revelations from God and believed herself to be pregnant with a child destined to be the new Messiah. By the 1820s such an outlook was gaining ground among Evangelicals. Here religion both reflected and reinforced the trend to Romanticism.

4.4 Political implications

In chapter VI of A Practical View Wilberforce broadens his perspective from the primarily spiritual emphasis of the earlier chapters to a consideration of the political implications of his analysis. In so doing he contributed to the ongoing debate on the French Revolution and the changing nature of British society and politics.

A Practical View can usefully be compared here with another work that gave considerable prominence to religion in the aftermath of 1789, Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790). To Burke the revolutionary attack on the Roman Catholic Church was one of the most disturbing features of events across the Channel, because he saw the Church as a key upholder of the continuity and tradition that he believed essential to duly regulated liberty and a safeguard against anarchy. What was important was not so much what the Church taught, but that it should remain as a source of institutional stability. The extent of Burke’s alarm on this score in 1790 might seem exaggerated, because the anti-Christian phase of the Revolution was still in the future. However, to Burke, even the Civil Constitution of the Clergy went much too far because it subverted the traditional nature of the alliance between Church and State by making the former clearly subordinate to the latter. A reformed, slimmed-down and government-controlled Church would be in no position to serve as the institutional brake on ill-considered change that Burke passionately believed to be necessary.

Click to view A Practical View, chapter VI

Exercise 3

Now read the extract from A Practical View, chapter VI, up to '... take up with superficial appearances' (pp. 277–8). On the basis of the summary of Burke’s views, in what respects do you think Wilberforce (1) agrees with Burke and (2) disagrees with him?

Discussion

-

Wilberforce strongly agrees with Burke in respect of the crucial importance of religion in general, and Christianity in particular, for political stability. You will probably have been struck by the way in which he just asserts this position, while saying ‘there can be no necessity for entering into a formal proof of its truth’, an indication of the extent to which it reflected a consensus among his contemporaries.

-

Unlike Burke, Wilberforce does not feel that the mere maintenance of traditional religious institutions is sufficient. He is worried that a decline in committed Christianity will lead to adverse political consequences and hence that Christian revival is essential for political security. (It is interesting to note that Burke, who died in 1797, read A Practical View on his deathbed, found it comforting, and wanted to thank Wilberforce for writing it; an indication that he had become receptive to Wilberforce’s perspective.)

4.5 The interaction of religion and society

Exercise 4

Now read the previous extract again with the associated commentary which draws out the key points and their significance, particularly in helping to understand the interaction of religion and society at this time. Wilberforce’s style, although long-winded, is not difficult to follow, but it is important not to become bogged down in the detail.

Discussion

Pages 278–82

Reasons are given as to why Christianity (or, rather, Wilberforce’s ‘real Christianity’) is in decline. Persecution, he suggests, is a stimulus to faith, but the current position of the Church is too comfortable. It has considerable civil privileges and links to ‘almost every family in the community’. (By ‘community’ here Wilberforce again appears to be thinking only of the ‘higher and middle classes’.) Commercial prosperity and general cultural progress give rise to greater materialism and a more relaxed morality, with the looser standards characteristic of the higher classes tending to diffuse downwards in the social scale. Although explicit disavowal of Christianity remains rare, it is losing its practical influence on society and morality, and outright rejection is likely to follow. Wilberforce then acknowledges that he is arguing from probabilities rather than actual observation, but claims that the reality fits the model he has presented.

In this passage Wilberforce unwittingly anticipated a key strand in the arguments of those historians and sociologists who have maintained that during the era of the Enlightenment there began an ongoing ‘secularisation’ of the western world, with the enforced retreat of religion from the centre to the margins of daily life. The ideological critique of traditional Christianity by Enlightenment thinkers is seen as important in this process, but greater emphasis is placed on the social changes associated with the Industrial Revolution. The difficulty for religion here was not, as Wilberforce thought, increased material prosperity as such so much as its consequences in terms of what has been called the ‘disenchantment’ of the world. This means that industrial and urban patterns of life became increasingly mechanized and predictable, leaving less room for supernatural belief. On the other hand, the short-term consequences of industrialisation for religion were often much more positive. Churches and, especially, Dissenting chapels had an important place in the social fabric of expanding towns, providing a source of meaning and community in contexts that could otherwise be very anonymous. Moreover, Christianity came to play an important role in shaping the values of the expanding middle class. Arguably, Wilberforce’s own writing and influence were a significant factor in ensuring that in Britain at least religion responded actively to the challenge presented by industrialisation rather than being overwhelmed by it.

Pages 282–3

Wilberforce briefly mentions the presence of explicit unbelief among the literary elite, encouraged by those who in his opinion should know better, but he sees this as a symptom rather than a cause of the wider trend. He sees recent events in France – clearly he has in mind the outright de-Christianisation of 1793–4 – as showing where such tolerance of ‘infidelity’ can lead. Significantly, though, his horror is not (unlike Burke’s) directed at the Revolution as such, but rather at this particular phase in its development. Indeed, in the footnote he implies that he does not see the Revolution itself as either a consequence or a cause of moral and spiritual decline.

Pages 283–5

Wilberforce now addresses the objection that the level of religious commitment he is advocating would produce a society so preoccupied with spiritual matters that it would neglect the practical necessities of daily life. In response he first affirms the priority of following God’s commands in order to prepare for heaven, but then proceeds to argue that the general prevalence of Christianity would in fact be socially useful. According to Wilberforce, who cites the authority of St Paul in his support, it is a ‘gross… error’ for Christians to withdraw from their secular duties. Granted that Christianity is opposed to excessive acquisitiveness or ambition, obedience to God and trust in his overruling providence actually encourages Christians to be diligent and constructive members of society. Moreover, a nation of such true Christians would be a peaceful and respected presence in international affairs, and would only fight wars in self-defence.

Again, we can relate Wilberforce’s comments here to a recurrent issue in the practice and study of religion: the tension between what are called ‘world-affirming’ and ‘world-denying’ perspectives. Throughout the history of Christianity there have been individuals and groups who have felt that obedience to God requires withdrawal from normal everyday life. These have included desert hermits in the early Church, monks and nuns in the Middle Ages and thereafter, and small groups on the more radical fringes of Protestantism. Calvinist views, such as those of Cowper and Newton, could tend to encourage a state of mind in which believers, seeing themselves as a chosen (‘elect’) minority, separated themselves from society. Wilberforce, however, despite his admiration for the authors of the Olney Hymns, was not a Calvinist. He emphatically aligned himself with those who stressed rather the obligation of Christians to be actively and constructively involved in mainstream society. His was an influential voice in setting the predominant direction of Evangelicalism (which certainly had some world-denying tendencies), and in contributing to the shaping of a nineteenth-century British culture in which secular and Christian outlooks were by no means wholly polarised.

Exercise 5

Now read the rest of the extract from A Practical View As you read consider the following questions and make note of the answers.

-

Why, according to Wilberforce, is religion in general, and Christianity in particular, important for the well-being of society?

-

What does Wilberforce mean by ‘real Christianity’ (refer back if necessary to the earlier passages of the Practical View), and why is it a social necessity?

-

What does he think would be the consequences of a disappearance of religion, and how can these dangers be averted?

Discussion

-

Even ‘false Religion’ (by which Wilberforce means religions other than Christianity) can safeguard good order and morality in society by providing perceived supernatural sanctions to support human law (‘jurisprudence’). Christianity, however, is much more effective, primarily because its teaching checks inherent human selfishness. Note that Wilberforce takes social inequality for granted. The rich are criticised not for possessing wealth but for using it in excessive showiness or frivolousness rather than in benevolence towards others. While the poor have understandable cause for resentment when the rich flaunt their wealth or the powerful behave oppressively, they are otherwise expected to accept their situation in a ‘diligent, humble, patient’ frame of mind, because it has been assigned to them by the providence of God. Their life in this world (‘the present state of things’) is merely a period of preparation for eternal life in heaven in which rich and poor will share alike.

-

For Wilberforce, ‘real Christianity’ requires assent to central Evangelical doctrines of inherent human sinfulness and deliverance from divine condemnation by the atoning death of Jesus Christ on the Cross. He is insistent that the social benefits of Christianity will only be realised if adherence to it is sincere. Mere traditional respect for an Established Church will be insufficient (another contrast between Wilberforce’s position and Burke’s). If the rich themselves no longer think Christianity true, they cannot expect to delude the poor into accepting it either. A rational and ethical view of life may appeal to the higher classes, but in order to win over the ‘lower orders’ religion needs to capture their emotions. (Although Wilberforce does not explicitly refer to Methodism, he must have been aware of its rapid growth in his own Yorkshire constituency at this very period and here he hints at a key reason for its appeal. More broadly he combines significant elements of a developing Romantic mindset by linking a consciousness of the presence of the ‘lower orders’ (an awareness of a ‘working class’ as such is not part of his vocabulary) to a recognition of the emotional and irrational aspects of human nature.)

-

The disappearance of religion would lead to the collapse of civil society. Given recent developments in France there can be no complacency about the dangers. These can be averted by a recognition that the root problems are moral (and spiritual) rather than political, and need to be addressed by people of status and influence setting a firm example of determined and uncompromising commitment to Evangelical Christianity. Wilberforce regards this as a matter of patriotism as well as of religion if the perceived moral poison arising in France is to be contained. The advance of true religion would bring substantial moral and political benefits quite apart from the providential blessing of God.

4.6 Contemporary reactions

Wilberforce’s underlying conservative inclinations and his vested interest in the existing social order led him to emphasise those aspects of Christianity that are conducive to stability rather than the more radical strands of Jesus’ teaching. Nevertheless, there is no doubt of Wilberforce’s absolute conviction of the reality of an afterlife and, consequently, of the spiritual perspective in which life as we know it has to be viewed. Herein was an outlook fundamentally different from that of David Hume, whose emphasis on empirical knowledge and scientific method made him sceptical of the claims of religion. Wilberforce’s perspective though was probably much more representative than Hume’s of the consensus of contemporaries. It shows why for social and political reasons, as well as for philosophical and theological ones, any questioning of the immortality of the soul seemed so dangerous and shocking.

The Practical View stirred extensive comment and debate among contemporaries. According to Daniel Wilson it was:

at the same moment, read by all the leading persons of the nation. An electric shock could not be felt more vividly and instantaneously. Every one talked of it, every one was attracted by its eloquence, every one admitted the benevolence and sincerity of the writer.

(Wilson, 1829, op. cit., p. xviii)

The Gentleman’s Magazine (vol.67, part 1, p. 411), which might be regarded as representative of the polite society of ‘professed Christians’ to which Wilberforce addressed himself, ‘sincerely’ wished him success in his labours. The reviewer felt his picture both of contemporary religious practice and of true Christianity was a fair one. The Anglican British Critic (vol.10, pp. 294–303) hailed the Practical View as ‘one of the most impressive books on the subject of religion, that appeared within our memory’. It noted that many people were censuring the book as too severe, but they were merely trying to excuse their own indifference and in doing so confirmed the truth of Wilberforce’s central contentions. It found the Practical View overly sympathetic to Methodism, but readily pardoned this fault as only a slight blemish on an otherwise excellent work. At the same time Dissenters influenced by Evangelicalism warmly welcomed the book’s advocacy of religious convictions and practice with which they identified. The Protestant Dissenters’ Magazine (vol. 4, pp. 196–8) praised the work, trusting that it would ‘meet with more than common attention’, although it was critical of Wilberforce’s diffuse style which was thought to detract from the clarity of the argument, a frustration shared by many later readers.

Individual reactions could be profound. Arthur Young, an eminent pioneer of new methods in agriculture, bought the book and read it ‘coldly at first’. He initially failed to understand the doctrinal points, but read it again and again ‘and it made so much impression on me that I scarcely knew how to lay it aside’. After reading the book for a fourth time within a few months, Young was ready to dismiss criticism of Wilberforce as ‘arrant nonsense’ and wrote that ‘my mind goes with him in every word’ (quoted in M. Betham-Edwards, 1898, The Autobiography of Arthur Young with Selections from his Correspondence, London, Smith, Elder and Co., pp. 287–8, 297). Similarly, when Thomas Chalmers (1780–1847), the future social reformer and leader of the Free Church of Scotland, read the book in the winter of 1810–11 it placed him ‘on the eve of a great revolution in all my opinions about Christianity’.

Other commentators, however, thought the book ‘fanatical’ (J. Pollock, 1977, Wilberforce, London, Constable. p. 153). This perspective showed the continued prominence of a strain of Enlightenment thought in which everything must be viewed in the cool light of reason. The Gentleman’s Magazine qualified its positive review by expressing unease lest Wilberforce’s advocacy of emotion in religion should ‘transport warm tempers beyond due bounds, and expose them to temptation and to censure’. The Monthly Review (vol. 23, pp. 241–8) professed itself as much a friend to religion as Wilberforce was, but firmly maintained that ‘in the present day, if its authority be preserved at all, it must not be done by addressing the passions, but by appealing to reason’. The success of Wesley and Whitefield in ‘reforming and civilising’ the poor depended on stirring the ‘passions of the vulgar’ and was no proof of the truth of their teaching. Religious practice was more important than assent to abstract doctrines, which were likely soon to be perceived as erroneous and so to lose their authority. Criticism of this kind, however, had the unintended effect of enhancing the appeal of the Practical View among more orthodox Christians. Meanwhile, Wilberforce was denounced in pamphlets by a couple of Unitarian writers. (Unitarians were Dissenters who professed a strongly Enlightened and rational view of religion, tending to discount the supernatural and to emphasise the unity of God rather than the divinity of Jesus Christ.) One held that his fundamental principles were absolutely incompatible with those of Christ himself (G. Wakefield, 1797, A Letter to William Wilberforce, Esq. On the Subject of his Late Publication, London, p. 4), and the other attacked his doctrine as ‘inconsistent with reason, unfounded in Scripture, and injurious to morality’ (T. Belsham, 1798, A Review of Mr Wilberforce’s Treatise, London, J. Johnson, pp. 2–3). Nevertheless, the Duke of Grafton, a former prime minister who was sympathetic to Unitarianism, although thinking that Wilberforce laboured under ‘great but involuntary errors’, praised him as ‘an upright, sincerely pious and beneficent character’ (quoted in Betham-Edwards, 1898, op. cit., pp. 325–6). Such reactions revealed something of the range of contemporary perceptions of what it meant to be genuinely religious amidst the interplay of Enlightenment and Romantic cultural and social expectations.

Exercise 6

Now that you have read through some extracts from Wilberforce’s A Practical View, pause for a moment to review your own reactions to the text, and summarise your thoughts on the following questions.

-

What is distinctive and interesting about the text?

-

How does it fit into the processes of transition from Enlightenment to Romanticism?

Discussion

-

Perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of the text is the evident centrality and sincerity of Wilberforce’s religious mindset and motivation, and his specific commitment to Evangelical Christianity. Moreover, he does not advocate a spiritual withdrawal from the world of mainstream politics and society, but insists that Christians should be fully engaged with it. Despite his evident unease about the current moral and political state of Britain, his religious language is too earnest to be merely a cover for some other underlying motive, such as a conservative political agenda. A text such as this is therefore an important corrective to the impression that this was an era in which religion was generally in retreat in the face of Enlightenment rationality. We need to recognise that the overall picture was a complex and variegated one.

Of course the question is an open-ended one, and other lines of thought could be developed, focusing perhaps on the nature of Wilberforce’s response to the French Revolution, or on his perception of the structure and workings of British society. Such issues are also well worth reflecting on, but it remains important to recognise the pivotal role of religion in A Practical View.

-

In summary this is very much a text that combines an Enlightenment appeal to structured rationality with a Romantic one to emotion and the supernatural, although the reactions of the contemporary reviewers suggest it was perceived as emphasising the latter more than the former. The ease with which Wilberforce moves from one mindset to another is a useful caution to us against simplistic pigeonholing of people as either ‘Enlightenment’ or ‘Romantic’ thinkers. The Practical View also raises for us the question of how important religion itself was as a force that promoted cultural change as well as reflecting it. There are no easy answers to such complex questions, and they are worthy of further reflection.

5 Wilberforce and slavery

5.1 Leading the fight against slavery

Wilberforce’s name has been most famously associated with the issue of slavery. His success as a leader of the cause against slavery stemmed from his capacity to marshal a formidable range of argumentation, including secular as well as spiritual factors, and practical considerations as well as statements of principle. This section will examine extracts from two of Wilberforce’s writings on slavery, A Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade (1807) and An Appeal to the Religion, Justice and Humanity of the Inhabitants of the British Empire, in Behalf of the Negro Slaves in the West Indies (1823). This will also lead to an examination of interactions between Britain and the non-European world. The focus here will be on Wilberforce’s religious arguments against slavery. As might be expected from the arguments in A Practical View, Wilberforce’s religion was a fundamental feature of his anti-slavery motivation.

In his commitment to the campaign against the slave trade Wilberforce both represented and encouraged a growing identification of the Evangelical movement as a whole with the anti-slavery cause. In 1774 John Wesley had published a powerful denunciation of the trade, ending with a direct appeal to ships’ captains, merchants and slave-owners to repent of their sinful involvement in it or risk incurring the wrath of God. Both the authors of the Olney Hymns contributed their eloquence to the campaign. In 1788 John Newton published his Thoughts on the African Slave Trade, in which he began by confessing his own past involvement. Although he had found it ‘disagreeable’ he had not had moral scruples at the time. He saw his own subsequent change of heart as perhaps representative of the nation at large. He now saw the slave trade as a wickedness that would lead to ruin and, vividly drawing on his first-hand knowledge, exposed the cruelties and degradation to which the Africans were subjected. In the same year Cowper wrote ‘The Negro’s complaint’, in which the poet perceived natural disasters as divine punishment for oppression and exploitation:

Hark – He [God] answers. Wild tornadoes

Strewing yonder flood with wrecks,

Wasting Towns, Plantations, Meadows,

Are the voice with which he speaks.

In April 1792 he addressed a sonnet to Wilberforce, encouraging him to persist in his labours:

Thy Country, Wilberforce, with just disdain

Hears thee by cruel men and impious call’d

Fanatic, for thy zeal to loose th’enthrall’d

From exile, public sale, and Slav’ry’s chain.

Friend of the Poor, the wrong’d, the fetter-gall’d,

Fear not lest labour such as thine be vain.

Thou hast atchiev’d a part; hast gain’d the ear

Of Britain’s Senate to thy glorious cause;

Hope smiles, Joy springs, and though cold Caution pause

And weave delay, the better hour is near

That shall remunerate thy toils severe

By Peace for Afric, fenced with British laws.

Enjoy what thou hast won, esteem and love

From all the Just on earth and all the Blest above.

In the 1790s the campaign against the slave trade nevertheless languished in the face of a sense of national crisis due to the war with France, rebellion in Ireland and unrest at home. There was a temporary peace with France in 1801, but war resumed in 1803 and was to continue until the battle of Waterloo in 1815. It was in 1804, however, that the political tide began to turn decisively in Wilberforce’s favour, and in 1806 he seemed at last to be on the verge of victory. In this context early in 1807 he published his Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade Addressed to the Freeholders and Other Inhabitants of Yorkshire. Despite its title this was no short pamphlet, but a 350-page book intended to restate the abolitionist arguments used during the previous two decades in time for the parliamentary session in which, Wilberforce hoped, the measure would eventually be passed. It was formally addressed to his Yorkshire constituents, but the real target audience was the members of the House of Lords and the House of Commons on whose votes the outcome now depended.

Wilberforce began the book by affirming that his dominant motive for writing was concern for ‘the present state and prospects’ of Britain. He continued:

That the Almighty Creator of the universe governs the world which he has made; that the sufferings of nations are to be regarded as the punishment of national crimes; and their decline and fall, as the execution of this sentence; are truths which I trust are still generally believed among us … If these truths be admitted, and if it be also true, that fraud, oppression and cruelty, are crimes of the blackest dye, and that guilt is aggravated in proportion as the criminal acts in defiance of clearer light, and of stronger motives to virtue… have we not abundant cause for serious apprehension?… If… the Slave Trade be a national crime… to which we cling in defiance of the clearest light, not only in opposition to our own acknowledgements of its guilt, but even of our own declared resolutions to abandon it, is not this, then a time at which all who are not perfectly sure that the Providence of God is but a fable, should be strenuous in their endeavours to lighten the vessel of the state, of such a load of guilt and infamy?

(Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade, 1807, pp. 4–6)

In the body of the book Wilberforce concentrated on a systematic overview of the sufferings and hardships of the slaves. He began by looking at the situation in Africa, during which analysis he referred extensively to the evidence provided by Mungo Park’s Travels. He then turned to the horrors of the voyage across the Atlantic, and finally and most extensively to conditions in the West Indies themselves. He argued that these would be improved by the abolition of the slave trade because the plantation owners, no longer able to obtain fresh supplies of labour, would be obliged to treat their existing slaves better. Repeatedly however, amidst the accumulation of factual evidence and carefully reasoned argument, Wilberforce’s religious zeal resurfaced. Thus for him exploitation of Africa was especially reprehensible because it was a barrier against ‘religious and moral light and social improvement’ and was a persistent depraving and darkening of ‘the Creation of God’. The material sufferings of the slaves in the West Indies were bad enough, but worst of all was the denial to them of ‘moral improvement, and the light of religious truth, and the hope full of immortality’.

Click to view Extracts from Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade

Exercise 7

Click the pdf (above) to read short extracts from the Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade which come from part of Wilberforce’s discussion of conditions in the West Indies, and then from the concluding section of the book. They enable you to get something of the flavour of the style and argument, particularly in illustrating the religious motivation for Wilberforce’s campaign. As you read, consider the following questions and note your answers.

-

What arguments for abolition does Wilberforce put forward here?

-

How do you think his arguments were received by Parliament in 1807?

Discussion

-

First, no serious attempt is made to convert the slaves to Christianity, the only thing in Wilberforce’s eyes that would represent some recompense, if not justification, for their bondage. Second, whereas Christianity was instrumental in bringing about the abolition of slavery in the ancient world, Protestants are now conniving in a particularly unpleasant form of contemporary slavery, being shamed by the superior humanitarianism of Roman Catholics, Muslims (‘Mahometanism’) and even pagans. Third, unless the trade is abolished, the ‘heaviest judgements of the Almighty’ will ensue, an argument to which Wilberforce gives particular weight and with which he concludes the Letter. Note that when Wilberforce writes of divine judgement he is not envisaging dramatic and unexpected fire and brimstone, but rather the ongoing ‘operation of natural causes’ by which ‘Providence governs the world’. His conception of God in this passage is thus of a rational and consistent deity who controls the world in an orderly and predictable fashion through the normal processes of nature and human society, an essentially Enlightenment rather than Romantic understanding of the cosmos.

-

Britain was at war in early 1807 (Nelson’s victory and death at Trafalgar had occurred little more than a year before in October 1805). In this context of insecurity, therefore, arguments presenting the slave trade as a blot on national moral righteousness, and suggesting that decline and disaster might be the price to be paid for continuing it, were likely to fall on receptive ears. Wilberforce turned on its head the widespread perception in the more immediate aftermath of the French Revolution that significant change was too risky to contemplate: his stance now was that it was too dangerous not to change.

5.2 Wilberforce’s anti-slavery campaign in context

Certainly the outcome was a positive one from Wilberforce’s point of view in that abolition of the slave trade in British ships and colonial possessions passed rapidly through both Houses of Parliament, and became law in March 1807. This result in part implied an increased receptivity to Wilberforce’s religious arguments against slavery, but there were also other factors at work. These included the advance of liberal ideas of justice and toleration, themselves reflecting the influence of the Enlightenment, which increasingly made the oppression of Africans seem less acceptable. Crucial too in 1807 was government support for abolition, which had been lacking at earlier stages of Wilberforce’s campaign.

Wilberforce’s campaign against slavery needs to be seen in the context of growing interest in the world outside Europe, a reflection of expanding colonial involvements, notably in India, and increasing cultural interchange. In the specifically Evangelical context this interest was reflected in the foundation of various missionary societies during the 1790s, including in 1799 the Church Missionary Society, in which Wilberforce took an active part. An earlier significant initiative had been the creation in 1791 of the Sierra Leone Company, which Wilberforce and others hoped would provide a basis for legitimate commerce and the spread of Christianity in West Africa. To twenty-first-century secular eyes there might appear something surprising in Wilberforce’s simultaneous involvement in the campaign against slavery, which is still viewed as courageous progressive humanitarianism, and his advocacy of foreign missions, now often perceived as a feature of offensive western cultural imperialism. In Wilberforce’s mind, however, anti-slavery and missions were not only linked but two sides of the same coin. We have already seen this outlook reflected in his concern for the Christianisation of the slaves. It was evident again in 1813 when he vigorously and successfully advocated that missionaries should be allowed to operate in British India. Hindus, he thought, were ‘fast bound in the lowest depths of moral and social ignorance and degradation’. He saw both missions and the campaign against slavery as opening the way to ‘Christian light and moral improvement’ (1813, pp. 48, 106).

In 1814 the initial defeat of Napoleon seemed to Wilberforce and others to provide an opportunity to put pressure on continental European countries to join Britain in abolishing the slave trade. Wilberforce lobbied hard for the peace settlement with the new French government under the restored Louis XVIII to include immediate French abolition in exchange for the return of colonies seized by Britain during the war. He was bitterly disappointed when France only agreed to abolish in five years’ time, a commitment that he feared would be unenforceable. He drew comfort, however, from the strong support for his position expressed not only by British public and parliamentary opinion, but also by Tsar Alexander I of Russia. Moreover, in March 1815 Napoleon, following his return from Elba, reversed his previous policy and decreed the total abolition of the French slave trade. The subsequent Bourbon government stood by this decision, although, as it did not actively enforce it, evasion was widespread. Meanwhile, later in 1815 the Congress of Vienna issued a declaration against the slave trade, which caused Spain and Portugal also gradually to edge towards abolition. Although slavery in the Americas was to continue for many decades and was only to end in the United States in the 1860s after a violent civil war, pressure for abolition was now gathering momentum and becoming internationalised.

In the meantime, the continuing background of armed conflict in the Napoleonic Wars until final victory over Napoleon at the battle of Waterloo in June 1815 tended to reinforce a trend within Evangelicalism towards conceiving God’s intervention in the world in more apocalyptic and less orderly terms. It was a particular religious manifestation of the trend to Romanticism. There was increasing interest in the study and interpretation of the prophetic books of the Bible, particularly Daniel in the Old Testament and Revelation in the New Testament, which were held to include predictions that were as yet unfulfilled. For example, in 1815, shortly before Waterloo, James Hatley Frere (1779–1866) published A Combined View of the Prophecies of Daniel, Esdras and St John [Revelation], Shewing that all the Prophetic Writings are Formed upon One Plan. A central feature of Frere’s argument was the identification of Napoleon with a ‘vile person, to whom they shall not give the honour of the Kingdom’ (Daniel, 11:21, Authorised Version), whose career was foretold in the Old Testament, and whose eventual defeat would usher in the end of the world. Expectation of cataclysmic divine judgement tended, if anything, to gain further ground after 1815, in the face of unrest and hardship in the aftermath of the war. In November 1817 the death in childbirth of Princess Charlotte, second in line to the throne, was widely regarded by preachers as retribution from the Almighty for the sins of the nation.

Wilberforce’s final substantial published statement on slavery appeared in 1823. By this time the evident failure of the abolition of the slave trade to produce a marked improvement in the conditions of those slaves already in the West Indies led him and others to begin the campaign for the freeing of slaves in British colonies. He was now ageing and in failing health and was shortly to retire from Parliament. An Appeal to the Religion, Justice and Humanity of the Inhabitants of the British Empire, in Behalf of the Negro Slaves in the West Indies was therefore something of a political testament. It was intended to motivate his supporters for a sustained further period of agitation in which he himself would be unable to be an active participant. The extracts reproduced here are particularly concerned with the religious arguments against slavery which were, if anything, even more prominent in the 1823 Appeal than in the 1807 Letter.

Exercise 8

Click the pdf to read the extracts from the Appeal and note down answers to the following questions.

-

What are the seven main arguments for freeing the slaves that Wilberforce advances?

-

What does the text reveal about Wilberforce’s attitudes to the non-European world?

Discussion

-

-

(a) Slavery is inherently immoral and unjust because it degrades human beings.

-

(b) The slaves are unable to gain religious and moral instruction.

-

(c) The moral and educational condition of Blacks is worse in the West Indies than it was in Africa before they were enslaved.

-

(d) Slavery is an enormity inconsistent with the Christian and humane professions of the British nation.

-

(e) Personal independence, human dignity, and ‘the consolations and supports’ of religion require emancipation from chattel slavery.

-

(f) Under present circumstances (with the danger of slave revolt) the protection of the colonies is a great burden on British manpower and resources. Freed slaves, on the other hand, will under Christian instruction become a ‘grateful peasantry’, a basis for social and political stability in the West Indies.

-

Above all Wilberforce is fearful of impending divine retribution if slavery continues. Significantly, he has moved away from a perception that God will operate through the predictable if inexorable workings of providence towards a consciousness of more sudden and unforeseeable judgement.

-

-

Wilberforce is profoundly unsympathetic to non-European cultures, making hostile comments about both Africa and India. It is evident, however, that this lack of sympathy stems primarily, if not entirely, from the fact that they are not Christian and are hence – inevitably in Wilberforce’s opinion – degraded by superstition and immorality. He is though no racist, as is clear from his comparison of the good qualities of Africans in their homelands with their degraded state when enslaved in the West Indies. Non-European peoples have genuine potential to improve their lot by conversion to Christianity and/or emancipation from slavery.

Wilberforce’s conviction of the central importance of Christian conversion for individuals and societies was thus a consistent theme in his writing and speaking. In 1797 in the Practical View he had presented a recovery of ‘real Christianity’ as the only effective solution to the social and political malaise that he felt afflicted Britain. In relation to slavery, while he was happy to deploy an extensive armoury of rational argument, his underlying preoccupations were that the British nation should be true to its Christian identity, and that the slaves themselves should have the opportunity to hear and respond to the Christian Gospel. Herein for him lay the path not only of religious duty but of national self-interest, because in the West Indies, as in Britain, a Christian people would also be an orderly one.

6 Conclusion

William Wilberforce died on 29 July 1833, two days after hearing that the legislation for the abolition of slavery in British dominions had successfully completed its passage through the House of Commons, a fitting conclusion to the work he had begun nearly half a century before.

The Practical View both reflected and contributed to a major shift in religious consciousness of which the continuing growth of the Evangelical movement was the most striking manifestation. Methodist numbers may again be taken as an indicator. These showed a further steep increase in membership in England from 91,825 in 1801 to 143,311 in 1811, 215,466 in 1821 and 288,182 in 1830, which amounted to 3.4 per cent of the total adult population. The upward trend continued in the 1830s and 1840s. These numbers may still seem relatively small in relation to the population as a whole, which was also rapidly increasing, but they represented only the committed core and Sunday attendances would certainly have been considerably higher. In the meantime, not least because of the enhanced respectability conferred by Wilberforce and his associates, Evangelicals within the Church of England became increasingly socially acceptable, and even fashionable, and their numbers also grew substantially. There are indeed grounds for seeing the impact of the Practical View and the wider advance of Evangelical ideology as a key strand in the process by which during the early nineteenth century an emergent middle class defined its identity against the perceived irreligion and lax morality of the aristocracy.

Such religious revival and reorientation fitted into a wider North Atlantic and European pattern. In America Evangelicalism grew even more rapidly than in Britain and was, if anything, even more influential in shaping cultural and social outlooks. On the Continent the years after 1815 saw a recovery in the fortunes of the Roman Catholic Church, notably in France where there was a strong reaction against the irreligion of the revolutionary years. Such trends had their own dynamics, but insofar as they represented a recovered sense of historic identity and a deeper awareness of emotion, the supernatural, and the sharp polarities of good and evil, sin and salvation, they are linked to the overall cultural shift to Romanticism.

Wilberforce’s career was also of pivotal significance in terms of the relationship between Europe and the wider world. The campaign against slavery was a fundamental challenge to prevalent assumptions that ‘unenlightened’ non-European peoples and resources were merely subordinate and inferior and could be ruthlessly exploited. While the Christianising impulse that drove Wilberforce and the Evangelicals carried its own assumptions of superiority over other religions and cultures, it was at the same time a powerful force for asserting the dignity and worth of every human being, of whatever race.

References

Further reading

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Professor John Wolffe.

This free course is an adapted extract from the course A207 From Enlightenment to Romanticism, c.1780–1830, which is currently out of presentation

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material within this course:

Course image: Thomas Rowlandson in Wikimedia available in the public domain.

Figure 1 John Rising, “William Wilberforce”, oil on canvas, 220 x 130 cm, Wilberforce House, Hull City Museums and Art Galleries. Photo: Bridgeman Art Library

Figure 2 James Gillray, "Copenhagen House 1795", etching on paper, Corporation of London Libraries and Guildhall Library, London. Photo: Courtesy of the Corporation of London;

Figure 3 Anonymous, “Love Feast of the Wesleyan Methodists”, 1820, engraving. Photo: Mary Evans Picture Library, London;

Figure 4 Henry William Pickersgill, “Hannah More”, exhibited 1822, oil on canvas, 125.7 x 89.5 cm, National Portrait Gallery, London. Photo: © National Portrait Gallery London. NPG website

Figure 5 Frontispiece of "A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians, in the Higher and Middle Classes in this Country, contrasted with real Christianity", 1797, British Library, London. Shelfmark 1608/3553/T/P;

Figure 6 Richard Newton, “Fast Day”, 1793, engraving, 23.5 x 33 cm, British Museum, London. Photo: © Copyright the Trustees of the British Museum

John Rising, “William Wilberforce”, oil on canvas, 220 x 130 cm, Wilberforce House, Hull City Museums and Art Galleries. Photo: Bridgeman Art Library