Approaching literature: Reading Great Expectations

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 24 April 2024, 9:34 PM

Approaching literature: Reading Great Expectations

Introduction

In this coursewefocus upon a specific novel, and consider some of the different ways in which it can be read. We do this by identifying its genre, or the kind of writing it belongs to.

The novel as a kind of writing continuously involved in offering representations of the everyday, of the past and present world, is inevitably bound up with the different ways in which we have come to think about ourselves in relation to that world. Insofar as novels typically have a specific location in time and place, they are characteristically involved in the major upheavals of their societies, directly or indirectly: we are viewing the novel as a genre capable of registering in satisfyingly complex ways what we think we know about how the world we live in has come about. This goes beyond what used to be the dominant way of thinking about novels in this country —that they were basically moral, English and liberal, although of course many of the greatest novels can usefully be thought of in that way.

If a novel like Charles Dickens's Great Expectations (1860–1) may be thought of as a ‘classic’ example of the genre, then we would expect to find that the nature of its realism is more than simply a matter of the presentation of the moral growth of a single character. Depending upon how we choose to read it, it may also be about many other things, more or less apparent. In what follows, I want to suggest a range of approaches to this novel, each of which builds on its predecessor. To begin with, I consider how contemporary readers and critics viewed the novel — what sort of expectations they had — as a way of thinking about our expectations, and to question assumptions based upon the familiar, almost mythical, Dickens that we all think we know. Next, approaching the text as an ‘autobiographical’ type of novel, I look at how it takes us beyond the actuality of first person narrative — with which we so easily identify as readers — towards the realm of the gothic or ‘grotesque’. This enables me to proceed to a ‘hallucinatory reading’, derived from critics who explain the novel in terms of the fantasies of desire and revenge expressed through hidden psychic patterns linking the different characters. Finally, further questioning the idea that we should read Dickens's novel as realist in any simple sense, I take up the possibility that we should think of it as playing a part in the broader history of Britain, including its colonial history. It has been held that the mainstream realist novel did much to ‘normalise’ imperialist attitudes. I do not think things are quite so straightforward: apart from anything else, this presumes a very limited idea of the genre. Nevertheless, it takes us beyond the familiar, towards a reading that raises yet more possibilities for what we may find in the novel. My aim is to increase your sense of the genre's potential, not just to advocate any one reading, or place Great Expectations within a particular category.

Great Expectations has been published in many editions over time. In order to reference sections of the novel, we have chosen to use the 1994 edition (Oxford University Press, ed. M. Cardwell with an introduction by K. Flint). You may be reading a different version of the book, so the references will not be the same. However, they will give you an idea as to where to find the sections mentioned.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 2 study in Arts and Humanities.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

read and understand the classic novel Great Expectations, based on the genre of the book

study literature at a higher level.

1 Openings and ogres

1.1 The novel's opening

One important way of approaching the novel as a genre is to think about what expectations this kind of text would have aroused in its first readers. This is a way of reminding us of the gap between then and now, of the fact that readers of the original novel had certain assumptions, which would have been different from our own. It is a way of remembering the changing cultural-historical context, which will help us to make sense of a text, but also of reading with more awareness of what the process of reading involves. In order to help us to think about how our reading may be influenced by our conventions and assumptions, I would like briefly to consider a modern novel, which raises these issues quite sharply.

Activity 1

Here is the opening paragraph of a novel published nearly a century-after Great Expectations. How does it capture the reader's interest? What literary tradition or sub-genre is being referred to and why? What features, if any, does it have in common with the opening pages of Great Expectations?

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you'll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don't feel like going into it. In the first place, that stuff bores me, and in the second place, my parents would have about two haemorrhages apiece if I told anything pretty personal about them. They're quite touchy about anything like that, especially my father. They're nice and all – I'm not saying that – but they're also touchy as hell. Besides, I'm not going to tell you my whole goddam autobiography or anything. I'll just tell you about this madman stuff that happened to me around Christmas before I got pretty run-down and had to come out here and take it easy. I mean that's all I told D.B. about, and he's my brother and all. He's in Hollywood. That isn't too far from this crumby place, and he comes over and visits me practically every week-end. He's going to drive me home when I go home next month maybe. He just got a Jaguar. One of those little English jobs that can do around two hundred miles an hour. It cost him damn near four thousand bucks. He's got a lot of dough now. He didn't use to. He used to be just a regular writer, when he was home …

Discussion

This is the opening paragraph of The Catcher in the Rye (1951) by J.D. Salinger, and, like Great Expectations, it aims to capture our interest by immediately plunging us into the experience of an individual character, who tells us his story. As in Dickens's novel, that character is a young boy somewhat at odds with the world around him, in a way both funny and pathetic. The narrator in the modern novel explicitly recalls Dickens's David Copperfield (1849–50), but mentions the hero of that book only to deny that he is going to write the ‘kind of crap’ Dickens wrote and going on to assert that he will not tell us his ‘whole goddam autobiography or anything’ either.

The tendency towards exaggeration in the Salinger passage reflects a characteristic of young people's speech, but the form and content of the opening also establish a number of points about the text. First, the modern author is consciously participating in a tradition of first person, autobiographical narrative fiction, which Dickens helped to establish. This form of writing conventionally begins with an account of the narrator-hero's origins, childhood and parentage. Secondly, we are being reminded of that tradition or sub-genre in order to enjoy a consciously rude reaction against it. Thirdly, for all the naïvety of the narrator of the modern text, the author behind him is hardly naïve. Are we not, for instance, meant to feel more critical towards the boy narrator's family than he does? You might also have noticed that the specific allusion to David Copperfield clarifies the child narrator's gender, which is reinforced by the ‘pretend-tough’ tone. In Great Expectations, Philip Pirrip's name signals the gender of its autobiographical narrator, who is not going to tell us much about his parents either, not because they are touchy, but because they are dead. He, too, ignores or omits a lot of the ‘David Copperfield kind of crap’, although not in a self-aware, modern way.

Comparison of the two openings enables us to notice rather forcibly Dickens's manner of appealing to his readers. His narrative is first person, but, unlike the Salinger text, it involves an adult narrator looking back over a considerable time and so able to exercise adult judgements about himself. For example, he says that it was a ‘childish conclusion’ of his young self to imagine his dead mother ‘freckled and sickly’ on the basis of the gravestone inscription ‘Also Georgiana Wife of the Above’ (Dickens, Great Expectations, 1994 edn, p.3). We may also notice that what the narrator calls childish, in perhaps the negative sense, may be thought of more positively, in terms of a child's unconsciously acute perception of his mother's likely condition, at that time and with all those young and presumably sickly children. (I am not suggesting that any reader would think about all this on a first reading, by the way.)

This distancing effect, pulling us back to the adult narrator's perspective, and then further, to our own reading of that narrator's views, is reinforced by Dickens's way of handling time. Salinger uses the present tense, and his child narrator looks back just less than a year. Dickens uses the past tense, and has his narrator moving swiftly from a succinctly generalised past to ‘a memorable raw afternoon towards evening’, when the boy Pip realised ‘the identity of things’, and recalled himself as what the narrator goes on to call a ‘small bundle of shivers growing afraid of it all and beginning to cry’ (pp.3–4). The shift to the continuous tense brings the experience of feeling like a fragmented individual at the mercy of the elements right up into the present of its telling.

1.2 Perspective

Perhaps the most striking thing about the opening of Great Expectations is the way it combines the rhetorical immediacy of the speaking voice, and the closeness to the reader that invites, with this flexibility between different perspectives in time. Dickens thereby combines the ancient storyteller's art with more recent developments in narrative technique.

By ‘recent’, I have in mind the development of first person written narrative in the nineteenth century. There was a growing interest in the idea of a narrative retrospectively discovering a pattern of development in the young mind from within. (This was usually male, although Jane Eyre (1847) is the notable exception.) This type of autobiographical fiction is sometimes given the label Bildungsroman or apprenticeship novel (from Johann von Goethe's influential narrative of this type, Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship (1795–6)). However, a ‘confessional’ element, derived from religious (especially puritan) tradition, was equally important in the formation of the sub-genre.

In this kind of narrative, the moral focus on the individual, which, as we have seen, was central to the formation of realist fiction, became mapped onto stories of the thoughts and adventures of childhood. Most of the earlier authors working within the autobiographical sub-genre chose to tell their story from the perspective of the adult, rather than as if it were spoken by the child or adolescent. The latter could not be expected to express feelings or analyse situations except within a limited range and remain credible, and so could only offer the most indirect or attenuated sense of moral or spiritual values. The characteristic modern version of this type of narration was established by James Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916). The Catcher in the Rye shows the continuity of the modern way of representing the inner workings of the mind, in terms of an inner monologue or ‘stream of consciousness’, which aims at authenticity rather than morality.

As novelists themselves have long recognised, the choice of what ‘point of view’ to adopt is one of the most important decisions they have to make. Theorists have gone on to isolate many different aspects of this decision, perhaps the most important being the distinction between ‘who speaks’ and ‘who sees’. In the opening of Great Expectations, the speaker is the adult Pip, but the child Pip is the one who sees. This gap is vital for the exploration of memory as well as morality in the novel, and as it proceeds the adult narrator's voice and comments play an increasingly important part in the way the narrative is mediated.

The dual role or perspective is established from the first words, if only by implication:

My father's family name being Pirrip, and my Christian name Philip, my infant tongue could make of both names nothing longer or more explicit than Pip. So, I called myself Pip, and came to be called Pip.

This is the voice, not of the boy himself, but of the man, who can refer with light-hearted irony to the inadequacies of the ‘infant tongue’. In an act of self-identification explained by the next paragraph, the child gives himself a name associating him with his dead father, even as it registers his isolation from his unknown family. (Father-figures are especially important in what follows, as we shall see.) The second paragraph of the novel reinforces the suggestion of the creative power of the boy ‘fancies’ or imagination, at the same time as it offers a critical perspective upon that power: reading the grave inscriptions leads to unreasonable or childish images, which nonetheless sway us with their sympathetic or comic force.

The defining moment of Pip's life which follows is rendered with a touching melancholy, ‘a memorable raw afternoon towards evening’ (p.3), when childish fantasy is dissolved by the reality of the overgrown churchyard, his dead family and its gloomy environment. His sense of isolation and fear is suddenly dramatised by the appearance of the gruff stranger who threatens to murder and even eat him. The eruption of direct speech (‘Hold your noise!’), as a man ‘started up from among the graves’, takes us directly into the frightening present again: ‘A fearful man, all in coarse grey, with a great iron on his leg’ (p.4). Did you notice how this paragraph presents the man as the boy first sees him, with the minimum of narrative interference, by omitting the verbs from the first two sentences?

Activity 2

The first shocking appearance of the convict (well caught in David Lean's memorable film version of the novel, see Figure 1) brings into play another set of associations, which are critically important for our sense of the kind of novel we are dealing with here. How are we to respond to the convict's first appearance? By what means does the narrator mediate the ‘reality’ of this character to us?

Discussion

The convict's opening words (‘Hold your noise! … Keep still, you little devil, or I'll cut your throat!’, p.4) have just the exaggerated unreality we would expect of a stage or fairy-tale monster. Yet I think we accept his ‘reality’ because of the way Dickens presents the character: by making him not only something threatening as seen by the shivering child, but also something comic, as he becomes when mediated to us by the narrating adult. The humorous, ironic effect emerges, for instance, when the convict himself momentarily takes fright as Pip indicates that his mother is ‘There, sir!’ in the graveyard (p.5). The effect is confirmed when the convict tells Pip that if he does not do as he is told, there is a young man who will ‘get’ him even when he thinks he is safe in bed (‘in comparison with which young man I am a Angel’, p.6). Pip is terrified, but we are not – nor, clearly, are we meant to be. The distance between who sees and who speaks in this situation is explicitly indicated by the narrator's words when he describes the impression made upon young Pip as the convict leaves: ‘he looked in my young eyes as if he were eluding the hands of the dead people, stretching up cautiously out of their graves, to get a twist upon his ankle and pull him in’ (p.7).

With superbly grotesque precision – ‘cautiously’ seems particularly apt – Dickens suggests the fearful closeness of living and dead to the young Pip. At the same time, the boy's fancy anticipates something of importance for the novel as a whole, which may well work upon us unconsciously in a first reading. This is the power of the dead, the forgotten or unseen, unexpectedly to influence our lives. The manner of narration invites sympathy and understanding for the child Pip, but by reminding us of the adult narrator it offers a more detached perspective as well, making possible the ironic humour that plays about the entire narrative. The initial conception of the convict suggests gothic melodrama, but it is melodrama incorporated within a subtle artistic medium to produce complex effects within the reader.

Why does the term ‘gothic’ seem appropriate? Well, surely, the figure that ‘started up’ into Pip's view with such suddenness ‘from among the graves’, with his frightful glaring and growling, reminds us of that other creature from the dead who, as you may recall, caused a frightened young boy to cry out as he struggled: ‘Let me go … monster! ugly wretch! you wish to eat me, and tear me to pieces – You are an ogre’? Of course, Frankenstein's creature goes on to kill his victim (Shelley, Frankenstein, 1994 edn, p.117), whereas, for all his ogreish aspect, the convict in Great Expectations does not and, as we soon realise, would not. Shelley's creature tells his own story, distanced by being told to another narrator, whereas Dickens's ‘monster’ is seen from his potential victim's point of view. This makes his presentation in terms of what we might read as ‘gothic’ excess in fact rather plausible, since it can also be understood as the product of a young imagination replete with the monsters and ogres of folk and fairy-tale tradition. Moreover, this is a young imagination already sensitised by long infant meditation upon the family gravestones, amid the dreary winter marshes.

1.3 The serialised novel

That Dickens knew of Shelley's creature and may well have had him in mind is indicated by an explicit association very much later, after Pip finally learns the identity of his mysterious benefactor. He thinks of himself in the role of the ‘imaginary student pursued by the misshapen creature he had impiously made, [who] was not more wretched than I, pursued by the creature who had made me, and recoiling from him with a stronger repulsion, the more he admired me and the fonder he was of me’ (p.335). Curiously, Pip sees himself as in different ways comparable to both Frankenstein and the creature, a typically gothic doubling which yet arises plausibly enough in his consciousness.

In other words, the first person narrative provides a realist perspective upon happenings inherently gothic, melodramatic or non-realist in implication. Insofar as we are brought to share the boy Pip's viewpoint, we share his sense of the world as arbitrary and frightening; insofar as we are brought back from it by the adult narrator's viewpoint, we are invited to adopt a more ‘mature’ position, noting the plausibility of the child's and then the young man's experience.

I have used the word ‘grotesque’ to indicate the effect upon Pip's childish imaginings of the convict's appearance as it is conveyed to us, but also because this is the word Dickens himself thought of when the first inklings of this narrative came to him. The idea for the story began as an idea for a short essay by a semi-fictional adult narrator he had created for his magazine All The Year Round in January 1860, to recount recent experiences in town and country, and to delve into memories of his own childhood in Kent and London. As Dickens began to compose the essay, there came to him ‘a very fine, new, and grotesque idea’, he told his friend and biographer John Forster. ‘I begin to doubt’, he continued, ‘whether I had not better cancel the little paper, and reserve the notion for a new book … I can see the whole of a serial revolving on it, in a most singular and comic manner’ (Forster, Life of Charles Dickens, 1928 edn, p.733). By early October Dickens's hand was forced by the need to boost the circulation of All The Year Round, then falling as the result of a tedious serial by another writer. The new serial was to concern the adventures of ‘a boy-child, like David [Copperfield]’ and, to avoid any unconscious repetition, Dickens reread David Copperfield and was ‘affected by it to a degree you would hardly believe’. His approach to the new serial was to be more detached:

I have made the opening, I hope, in its general effect exceedingly droll. I have put a child and a good-natured foolish man, in relations that seem to me very funny. Of course I have got in the pivot on which the story will turn too – and which indeed, as you remember, was the grotesque tragicomic conception that first encouraged me.

The ‘very funny’ relationship between the child and the ‘good-natured foolish man’ is that between Pip and his sister's husband, Joe Gargery the blacksmith. The ‘grotesque tragi-comic conception’ upon which the whole mystery plot turns is, of course, the connection between Pip and the convict. The terms Dickens uses suggest popular theatrical or romance conventions, according to which distant or long-lost relations turn up when they can cause most surprise. Dickens had already published Hard Times as a serial to revive the fortunes of All The Year Round's predecessor, Household Words, a twopenny weekly begun in 1850 with the aim of casting ‘something of romantic fancy’ over ‘familiar things’ (ibid., p.512). When he hastily decided to put his new idea into All The Year Round, which had already seen the heartening effect upon sales of his historical romance, A Tale of Two Cities (1859), he planned a weekly serial of about the same length. It was to be much shorter than his other novels, normally published in twenty monthly parts, but would still be read over a lengthy period of time (Figure 2).

Activity 3

Like all Dickens's serializations, Great Expectations was also published in book form (in three volumes) shortly after its completion in the magazine. When speaking of serialization, he told an aspiring author: ‘There must be a special design to overcome that specially trying mode of production’ (Paroissien, Selected Letters of Charles Dickens, 1985, p.318, 20 February 1866). What do you think the fact of this magazine serial mode of production implies in terms of the author's relationship with his readers and with the characters and plot of the novel?

Discussion

The most obvious effect is that it helps the author-narrator, that is, the adult narrator not the boy Pip, seem close to his readers. We are likely to identify with him, to share his vision and judgements, and it may be difficult to realise that he is, after all, a fictional construct as much as the boy Pip. The serial mode of publishing fiction is bound to build up a powerful illusion of reality. However fanciful the treatment, we are likely to identify closely with a character or voice met repeatedly over an extended period of time, as in a television ‘soap opera’. In first person narrative, that character is the narrator.

If we are likely to identify sympathetically with characters we feel we come to know over time, we also need certain memorable features established and repeated to hold a long and complicated narrative in our minds. Dickens famously created a profusion of characters for his big novels, characters vividly defined so that they needed no reintroduction. Although there are fewer characters in Great Expectations, they exhibit distinctive verbal and/or physical mannerisms to keep them in the reader's mind. One of the most notable among the convict's mannerisms in the early chapters is a ‘click’ in the throat when his more sympathetic feelings are aroused (p.19), a little detail that recurs very much later (pp.316, 442). Another example of a memorable feature might be Mrs Joe's reputation for bringing her younger brother up ‘by hand’ (p.8), repeated whenever she appears in the earlier part of the book.

The relative brevity of Great Expectations meant that it required very tight control over the narrative plotting, including a note of suspense at the end of each weekly episode of one or two chapters, whereas for his other novels Dickens could afford a more leisurely pace.(The serialization plan for Great Expectations is given as Appendix C on page 487 of the 1994 edition of the novel cited throughout this chapter.) The three volumes of the book coincide with the three distinct and roughly equal parts of the plot. The first deals with Pip's childhood in Kent and the dissatisfactions set up by Satis House; the second with his life as a young ‘gentleman’ in and around Little Britain in London; and the third with the arrival of the convict, and Pip's attempts to save him, to forgive Miss Havisham and to be forgiven by Joe.

1.4 Summary

The abrupt and striking beginning of the novel, rich with anticipatory hints (not to mention the ‘pivot’ upon which the plot will turn), is obviously a good way to start a new serial as well as a new book. The evidence is that contemporary readers were very pleased. They were absorbed, they thought it a return to Dickens's comic vein, and sales soared. As modern readers, with a willingness to read more actively and seek meanings at a deeper level if so prompted, we nevertheless accept the illusion of reality that is, after all, vital to our involvement in the whole narrative. This is created at the very start by a range of familiar realist strategies, from the rendering of the boy's thoughts and impressions when he encounters the escaped convict, to the precise number of gravestones in the churchyard setting on the windswept marshes. The dating of the start of the story to one Christmas Eve in the early 1800s is suggested parenthetically on the first page, where we learn that Pip's parents ‘lived long before the days of photographs’ (p.3) (so he has to imagine what they looked like). It is made more explicit as we read on, by the preparations for Christmas dinner (p.13), by the appearance of the King's soldiers, and by many other clues (see p.77 and the editor's note on p.493).

At a time when the novel as a predominantly realist genre appeared to have stabilised, Great Expectations occupied a fairly recently established sub-genre, autobiographical fiction, but it also incorporated other generic possibilities, in particular those of Gothic fiction and popular melodrama. For example, when the convict first comes into Pip's view, he is like an emanation from the graves in the churchyard. He is marked all over his body by the landscape and he tells the boy he wishes he were a frog or an eel. He finally limps off towards the black and deathly gibbet on the river's edge, which had once held a pirate, looking as if he were that pirate ‘come to life, and come down, and going back to hook himself up again’ (p.7). The word ‘grotesque’ can be used to describe the surprising mixture of forms, characteristic of Dickens's writing, in which human, animal and vegetable seem to intermingle, but which is nonetheless designed to win our belief. Without winning that belief, Dickens cannot hope to engage us with the moral patterning of his text.

2 Grotesque expectations

2.1 Writing style

If, as I have been suggesting, the opening chapter of Great Expectations demonstrates a novel that employs melodramatic and Gothic techniques while maintaining its actuality as a first person narrative, how does this relate to our expectations as modern readers of Dickens? The trouble is, Dickens is too familiar. Most readers will have heard of the author, if not the novel, and many will have come across some other version of it, as a film, a television serial, a tape recording, a school text, a children's book – or, as Virginia Woolf said, as one of those stories like Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe or Grimms' Fairy Tales, communicated by word of mouth ‘in those tender years when fact and fiction merge, and thus belong to the memories and myths of life, and not to its aesthetic experience’ (‘David Copperfield’, 1925, quoted in Wall, Charles Dickens, 1970, p.273). This may seem to reflect something many of us feel about Dickens, but it also reveals a certain condescending assumption that Dickens's novels are less than art because they belong to the realm of childhood experience, the realm of ‘memories and myths’. Yet, as Woolf went on to acknowledge, Dickens's extraordinary powers have

a strange effect. They make creators of us, and not merely readers and spectators … Subtlety and complexity are all there if we know where to look for them, if we can get over the surprise of finding them – as it seems to us, who have another convention in these matters – in the wrong places.

Woolf was reviewing Dickens when his reputation was suffering from a general reaction against Victorianism, as evidenced, for example, in her friend Lytton Strachey's wittily irreverent Eminent Victorians (1918). She was, moreover, expressing the views of someone engaged in redefining the novel by means of her own more internalised, subjective kind of writing. However, her point is crucial. To read Dickens with full understanding, we have to become ‘creators’. This means that if, as modern readers, we do not expect to find subtlety and complexity in Dickens, this is not because it is not there, but because it is not where we expect to find it. We must search it out – we who have other ‘conventions in these matters’. What are our conventions in these matters? It is difficult to say, partly because these are to a large extent made up of habits of acceptance that are unconscious. For instance, we accept the artificial dialogue of a novel as ‘real’ although it is a construct, quite different from a recording of actual speech. In addition, what we accept in practice is so varied. Among the texts of our own time, for example, this might range from an experimental novel by John Fowles to a social realist novel by Margaret Drabble, from an historical romance by Georgette Heyer to a thriller by Patricia D. Cornwell, each written according to a different set of rules.

All these publications fall within broadly realist parameters, parameters that stubbornly persist long after realist strategies have lost their status as a ‘high’ art form, although they continue to be important in popular culture. As we have seen, historically the conventions of realism were accompanied, if not on occasion overturned, by alternative forms of representation. These included romance and Gothic fiction, which appealed to sufficient readers (if not always critics) to sustain them, and which continue in popular forms of writing. What is especially interesting about Dickens's writings is the degree to which they anticipate the continuing hybridity of genre expectations, although to his early readers his work simply confirmed the growing importance of realist assumptions. When Dickens published his first book – a collection of periodical essays and stories called Sketches by Boz (1836) – it was welcomed for its

fidelity of description, combined with a humour which, though pushed occasionally to the verge of caricature, is, on the whole, full of promise. But their principal merit is their matter-of-factness, and the strict, literal way in which they adhere to nature.

2.2 Dickens and his critics

With rare exceptions (generally from critics in other countries, such as Edgar Allan Poe or Ludwig Tieck), the published response to Dickens during his lifetime stressed the realist and ignored or disparaged the non-realist element in his work. However, as his use of caricature and fantasy became more apparent (for example, in A Christmas Carol, 1843), and as his popularity increased, some reviewers felt an obligation at least to try to come to terms with his kind of writing. Thus, G.H. Lewes hailed the early Dickens for his descriptive observation and truthful perception of character. Lewes subscribed to a simple but comprehensive definition of realism, according to which all art was a representation of reality, and the best art, like that of his partner George Eliot, was an accurate representation of reality. However, he could not define ‘by what peculiar talent Boz is characterised’, because the novelist mixed in so many other qualities, including such ‘absurdities’ against ‘nature’ as exaggerated characters, and incredible coincidences of plot (‘Sketches, Pickwick and Oliver Twist’, 1837, in Collins, Dickens, 1971, pp.64–8).

When Dickens responded to such criticism, which was rarely, he pointed out that ‘what is exaggeration to one class of minds and perceptions, is plain truth to another’ (preface to Martin Chuzzlewit (1867): 1951 edn, p.xv). Furthermore, as he argued in a letter to Forster:

It does not seem to me to be enough to say of any description that it is the exact truth. The exact truth must be there; but the merit or art in the narrator, is the manner of stating the truth. As to which thing in literature, it always seems to me that there is a world to be done. And in these times, when the tendency is to be frightfully literal and catalogue-like – to make the thing, in short, a sort of sum in reduction that any miserable creature can do in that way – I have an idea that the very holding of popular literature through a kind of popular dark age, may depend on such fanciful treatment.

Despite having been praised for it, Dickens opposed the ‘literal and catalogue-like’ tendency of the literature of his time, preferring a ‘fanciful treatment’ of his subject, by which he meant incorporating popular or subliterary genres like melodrama, fairy stories, Gothic tales and romances. Since this was at a time when writers such as Eliot and critics such as Lewes were trying to establish the novel as a serious, ‘high’ art form, increasingly realist in orientation, his approach was easily misunderstood.

The critic David Masson, in comparing Thackeray as a novelist ‘of the Real school’ with Dickens as a novelist ‘of the Ideal, or Romantic’, sensibly argued that ‘each writer is to be tried within his own kind [of writing] by the success he has attained within it’ (‘British novelists since Scott’, 1859, in Eigner and Worth, Victorian Criticism of the Novel, 1985, p.150). However, the distinction is too absolute, although Dickens would have agreed with Masson that his writing was ‘romantic’ in the sense that, as he said in the preface to Bleak House (1853), he ‘dwelt upon the romantic side of familiar things’ (1951 edn, p.xiv). This did not mean that he excluded everyday reality, or a certain level of representational accuracy. When he was criticised for the fact that a character in Bleak House was portrayed as dying by ‘spontaneous combustion’ (a widespread idea that the human body could burn up through internally generated chemical reactions), he referred to the ‘scientific’ evidence to support its plausibility. It was Lewes who attacked him for going beyond the bounds of the plausible, just as it was Lewes who, after the novelist's death, summed up Dickens's achievement by repeating all the standard charges against him, in particular his ‘susceptibility to the grotesque’, suggesting unreality to the point of madness (‘Dickens in relation to criticism’, 1872, in Collins, Dickens, 1971, p.573).

Views such as these typified the ‘cultivated’ or upper-middle-class response to Dickens for many years, with the result that, although his works have always been read in vast numbers, it has only been comparatively recently that they have been thought to deserve serious attention. The views of the critic F.R. Leavis were mentioned in Chapter Four, but Dickens's reputation as worthy of study at the highest level rests upon three pieces of criticism that preceded Leavis's The Great Tradition (1948) by several years. These are George Orwell's ‘Charles Dickens’ (Inside the Whale, 1940), Humphry House's The Dickens World (1941) and Edmund Wilson's ‘Dickens: the Two Scrooges’ (The Wound and the Bow, 1941). When Leavis argued that ‘Dickens is a great genius and is permanently among the classics’, he added to the growing weight of critical attention Dickens was receiving, only to undermine it at the same time by excluding all except one of Dickens's novels from the ‘great tradition’ of the English novel.

Leavis's argument, like Lewes's before him, turned on the legitimacy of Dickens's mixed kind of writing, in particular his use of melodrama. This, for Leavis, was a ‘low’ art form, making Dickens's art by association equally low, or at least just that of ‘a great entertainer’. For Leavis, the ‘adult mind doesn't as a rule find in Dickens a challenge to an unusual and sustained seriousness’ (The Great Tradition, 1960, p.19). Hard Times, escaped this damning judgement, despite the melodrama that most of us might find in it, because of its status as a ‘fable’, capturing the ‘key characteristics of Victorian civilization’ (ibid., p.20). Leavis's viewpoint, for all its narrow cultural élitism, was sympathetic to Dickens, but it was over twenty years before he and his wife Q.D. Leavis published Dickens the Novelist (1970), extending the ‘great tradition’ to all Dickens's ‘mature’ novels, of which Great Expectations was the last. According to Q.D. Leavis (whose broader knowledge of nineteenth-century fiction may have contributed to this revision): ‘The sense in which Great Expectations is a novel at all is certainly not to be arrived at by applying to it the ordinary conventions and assumptions derived from Victorian novels in general’ (Dickens the Novelist, 1970, p.288). In a chapter rather alarmingly called ‘How We Must Read Great Expectations’, she argued that Dickens found in this novel a ‘freer form of dealing with experience’ than the realist inheritance provided or than his readers expected, enabling readers to move ‘without protest, or uneasiness even, from the “real” world of everyday experience into the non-rational life of the guilty conscience or spiritual experience, outside time and place and with its own logic’ (ibid., p.289).

2.3 Surface realism – and beyond

Whether we are ever taken quite so far beyond the everyday is a moot point, but it is easy to see what she means in relation to Pip's guilty conscience, for example. Pip had always been treated ‘as if I had insisted on being born, in opposition to the dictates of reason, religion, and morality, and against the dissuading arguments of my best friends’ (p.23). This is a comical expression of the unpleasant contemporary emphasis upon children as little sinners who need to be bullied into virtue. The Christmas dinner at which all the adults except Joe attack Pip, morally speaking, seems to confirm this judgement. It represents the ‘real’ world of everyday experience, easily confirmed by historical evidence as well as our own awareness of how children can be terrorised by the righteous. However, there is also the child's way of seeing things – powerfully present to us as well – producing a sense of guilt so pervasive that it feels as if it is in the nature of things. Even the cattle look ‘clerical’ and accusing (p.17) and ‘when I and my conscience showed ourselves’ (p.21) we feel the boy's alienation as a non-rational state quite beyond what we might expect from someone brought up as he has been. Where does this come from?

The answer is revealed by Dickens's wonderfully sympathetic exploration of the inner dilemma of a boy caught between the demands of the terrifying, starving convict on the one hand and his inadequate surrogate parents on the other – the bullying sister with the ‘impregnable bib’ (p.8) and her submissive, child-like husband. We are told that his upbringing has made the child sensitive, and the adult narrator is quite severe about the inability of his young self to confess his ‘pilfering’ on the convict's behalf to Joe (pp.40–1). However, it is precisely this sensitivity that has led Pip to align himself with the outcast, against even Joe, leading to an irrational excess of guilt. He suffers a continual fear that his ‘criminal’ association will be discovered by the respectable citizens around him. For instance, when the man with the file arrives at the Jolly Bargemen with ‘two fat sweltering one-pound notes’ for him, he thinks of himself as on ‘secret terms of conspiracy with convicts’ (p.77).

By this stage in the novel the ‘freer form’ Dickens has adopted enables him to expand his narrative beyond surface realism, as shown in the first encounter with Miss Havisham and Satis House. This is where the second major thread of the plot begins, which is made explicit for us by the adult narrator's comment: ‘Pause you who read this, and think for a moment of the long chain of iron or gold, of thorns or flowers, that would never have bound you, but for the formation of the first link on one memorable day’ (p.71).

Activity 4

How does Dickens establish the first link in this second thread of the plot? How do you interpret the presentation of the wealthy woman and her surroundings in chapter VIII? Re-read especially pages 56–9. What elements in the ‘manner of narration’ direct us heyond surface realism?

Discussion

The link is established by the impact upon Pip of Miss Havisham and Estella. The meeting with the convict on the marshes will prove the source of his actual expectations, whereas this encounter will prove the origin of his false expectations. The ‘logic’ is not rational, the event is arbitrary, but it feels convincing, because of how it is handled. The narrative presents Miss Havisham as a grotesque creature, who appears at first as ‘dressed in rich materials’, ‘bright’ and ‘sparkling’, a ‘fine lady’, but who in the next paragraph becomes like ‘some ghastly wax-work at the Fair’, or ‘a skeleton in the ashes of a rich dress’ in one of the old marsh churches. The hidden association with the convict and the opening scene is hinted at when she lays her hands on her side as she says, ‘Do you know what I touch here?’ Pip is reminded ‘of the young man’, that is, the convict's threat of an imaginary young man who would ‘get’ him.

Miss Havisham's speech is patently unreal, the diction and rhetoric of melodrama, but we accept it because we are viewing her through the frightened boy's eyes, and we have been prepared for his fanciful yet suggestive vision of things. The stopped clock, the wedding garments and the closed room seem similarly melodramatic rather than realistic, but they provide by association an indirect expression of Miss Havisham's mental condition, confirmed later by what we learn of her history. Miss Havisham's gothic surroundings alert us to an understanding of her position beyond anything the young boy could see, although as the adult narrator informs us he ‘saw more’ in the first moments ‘than might be supposed’. Her corrupting potential is conveyed to the reader, even though the boy Pip remains unaware of the implications of what he sees.

Further, we can be brought to realise, by searching out significance in the places were we may not expect to find it, that this departure from realism serves to highlight the hidden and unexpected ways in which the narrative will articulate its meaning. There are hints, for example, of Miss Havisham's ambivalence, as witch or fairy godmother (both roles are referred to, see pp.83,154), which will eventually connect with the parallel ambivalence of the convict's role as benevolent uncle or vengeful father.

2.4 Summary

We do not have to share Q.D. Leavis's perception of the spiritual dimension of the novel to admit the mixed nature of Dickens's writing, its grounding in different fictional modes, which opens it up to many equally relevant and convincing readings.

However, to begin to develop a deeper insight into Great Expectations, we need to think more about how we approach this kind of writing. Like Pip, we may discover that our expectations have been based on some false or at least misleading premises. This is particularly so if we forget that the novel was published not only after familiar realist fictions of moral purpose such as Pride and Prejudice, but also after Gothic works such as Frankenstein, whose tales shadow Austen's orderly, coherent and humane world. This shadowing accompanies conventional views of the novel genre as one of realist formation, suggesting ways of writing that connect with the inner history of the psyche and the wider history of Britain in the world. The fact that today we are more aware both of the unexpected ways of the mind and of Britain's colonial history should encourage us to read Great Expectations, in a more challenging light than we expect of the familiar, mythical Dickens of childhood.

3 Hallucinatory reading

3.1 Details

Dickens employs popular sub-genres in a way that tries to persuade his readers to accept that there is another manner of stating the truth or, indeed, as we may see it now, that there are other kinds of truth, at a time when the trend was to be ‘frightfully literal and catalogue-like’. In practice, he does provide the kind of ‘superfluous’, ‘useless’ or ‘concrete’ detail crucial for what the critic Roland Barthes has usefully identified as ‘the reality effect’, an effect at the basis of narrative from the nineteenth century onwards. Without this element of depicting detail, the illusion of the real cannot be sustained. It is easy to find examples in Great Expectations. Almost at random (the randomness confirms the point), I might mention the sack of peas the narrator informs us is present in Pumblechook's front office, and on which his shopman takes his ‘mug of tea and hunch of bread-and-butter’ at eight o'clock on the morning that Pip and the pompous corn-chandler have breakfast, before Pumblechook delivers him to Satis House (p.53). Despite the gothic overtones of her first appearance, the illusion of everyday reality is sustained even in Miss Havisham's odd environment by, for example, added details of her jewels and trinkets, her ‘handkerchief, and gloves, and some flowers, and a prayer-book, all confusedly heaped about’ before her looking-glass (p.56).

Of course, such details are functional in other ways, adding something to the significance of each scene and character. Pumblechook is always associated with food and Miss Havisham is at least as confused as her ornaments, which here also signify the halted preparations for a wedding. Other novelists of the time similarly attempt to create the effect of reality with, at its best, a realism of detailed description that seduces the reader precisely through its detail. For example, we are told that a ‘necklace of purple amethysts set in exquisite gold-work, and a pearl cross with five brilliants in it’ (1994 edn, p.12) attracts the eye of Dorothea Brooke, who is introduced to the reader in the opening chapter of Eliot's Middlemarch (1871–2). In this case the detail also serves to confirm and develop the idea of a character whose psychology and background has just been given to the reader at some considerable length, over four pages.

Pumblechook's shopman has no further role in the novel by Dickens, and although Pumblechook's association with seedcorn continues – towards the end of the book his mouth is stuffed full of flowering annuals by the journeyman Dolge Orlick (p.461) – his inner life is never analysed. What about Miss Havisham, whose role is more central? Is her inner life offered to us? I think it should be clear that, despite the shared ground of realist detail, what Dickens intends to convey with details such as the trinkets and other paraphernalia with which he surrounds Miss Havisham is rather different from the use of detail by a novelist like Eliot. Dickens prefers not to analyse Miss Havisham's mind or feelings or personal history; instead, he presents us with a complex, highly suggestive image of what she is, and may become.

3.2 Moral development

I want to stress this aspect of Dickens's kind of fiction, because he is so often thought of as the novelist of the stereotypically obvious, with his tyrannical men, dried up women and pathetic children. Although there may be nothing wrong with being obvious, the point about Great Expectations is that it is most persuasive when it is not obvious. Various critics have tried to point out what is obvious about the novel (see, for example, Q.D. Leavis's ‘How We Must Read Great Expectations’) but the struggle to do so makes it seem less and less obvious. From the title, with its ambivalent overtones, to the two endings, neither of which is unambiguous, this is surely a novel that resists tying down to any simple message or summary?

It could be argued that one of the things it is about is precisely the inadequacy of the obvious. This is a function of its multi-genre status. If, for example, the novel seems obviously a classic story of self-education, of the rise of a young man from his rural roots towards metropolitan sophistication, then it also appears to undermine this very familiar Victorian tale. As Kate Flint says in the introduction (p.xvii), Pip's Bildungsroman is the ‘antithesis’ of those well-known and widely read contemporary chronicles of humble perseverance, such as Samuel Smiles's Self-Help (1859), which it calls to mind. Flint also relates Great Expectations to the contemporary vogue for sensation novels exemplified by Dickens's friend Wilkie Collins's The Woman in White (1860), with its ‘combination of crime, violence, a self-sequestrated woman, and the revelation of her ward's parentage’ (p.viii), although Dickens's book is also more than a novel of mystery and suspense. Flint proposes that Great Expectations is best seen in terms of the broad form of fictional autobiography. This is in line with her overall emphasis upon the novel's dramatization of ‘the issue of identity’, by means of which it participates in mid-Victorian attempts to show that work, loyalty and compassion are their own reward, while leaving ‘uncertain how Pip may prosper in the busy society of modern, urban Britain’ (p.xxi).

Activity 5

This impression of variety and uncertainty about the novel's status brings us back to the approach I am putting forward here: that we think about reading it as a text which draws on a mixture of artistic conventions, offering a multiplicity of meanings, depending upon which genre-frame or set of strategies we emphasise as readers. This is not to deny that to read the book only as an education novel is revealing, and makes sense of the story as a tale of personal moral development. To prove this point, first try and summarise the novel as a tale of individual moral development, and then consider what such a summary leaves out.

Discussion

This is the story of an orphan, Pip, who is brought up by his sister and her husband, the village blacksmith. Pip encounters and helps an escaped convict, and is later sent to call upon an eccentric heiress, whose ward, Estella, makes him despise his lowly origins, and with whom he falls in love. When Pip is of age, the heiress pays for him to be apprenticed as a blacksmith, but four years later he is told he has expectations of great wealth from a secret benefactor, whom he assumes to be the heiress. He departs to enjoy his good fortune in London, where he neglects his family and old friends and lives a life of dissipation and idleness. Pip's benefactor turns out to be the convict he met as a child who is recaptured and sentenced to death, with the loss of the wealth he made when he was deported to Australia. Meanwhile, Estella marries a boorish young man. Pip is left penniless and ill, but is nursed by his foster-father the blacksmith, who pays his debts, and from whom he learns humility and compassion. He finds work through a friend whose career he aided in secret during his time in London. Finally, he discovers that Estella has been mistreated by her husband and is humbled and a widow. However, the story does not make clear whether or not they eventually marry.

This is accurate as far as it goes, although even such a bald summary suggests the romance contours of the book's structure, its fanciful pattern of ironic revelation and its odd mixture of realistic and gothic or melodramatic associations. It is the latter two associations that take it beyond the plain articulation of a Bildungsroman. What such a summary most obviously leaves out is Pip's inner life.

3.3 Dickens' characterisation

I have suggested that Miss Havisham's psyche is indirectly revealed through the associations implied when Pip first sees her and her surroundings, but how do we learn about Pip himself? We need to consider this in the light of what I have been saying about Dickens's largely external way of reporting his story, from the distanced perspective of Pip as an adult. The answer to the question takes us back to Lewes's insinuation that Dickens's vision as a writer was grotesque and unreal almost to the point of insanity. What Lewes said was that Dickens's imaginative power was comparable to the hallucinations of the insane, except that in his case the hallucinations had the ‘coercive force of realities’. Unreal and impossible as creations like Miss Havisham are, ‘speaking a language never heard in life, moving like pieces of simple mechanism always in one way’ (‘Dickens in relation to criticism’, 1872, in Collins, Dickens, 1971, p.572), they nonetheless persuade us uncritical readers to believe in them, and not simply by means of descriptive detail. Lewes thereby implied something very important about the novelist's work that I would like to explore. The suggestion is that Dickens touches on submerged or repressed areas of the personality, which can only find expression indirectly or through unexpected, even disturbing, yet persuasively vivid associations.

It was not until Wilson's 1941 essay, ‘Dickens: the Two Scrooges’, that this suggestion was developed (under the twin influences of Jung and Freud) as a serious critical viewpoint. According to Wilson, Dickens's brilliant public persona as a successful comic novelist and energetic social reformer was a cover for the deep pain he always felt as a result of his own sense of shame and rejection as a child – when he had to work in a boot-blacking factory at the age of ten, and his family were imprisoned for debt. This pain, said Wilson, emerged in his fascination for outcasts, criminals and murderers, often coupled with a sympathetic portrayal of neglected children such as Oliver Twist – or Pip. Pip can thus be understood as like his creator in being both inside and outside the society of mid-Victorian Britain. This is revealed in his relationships with Joe and the convict Abel Magwitch, Estella and Miss Havisham, and the curious parallels and similarities they imply.

This sort of approach tends to underplay the art of the writer, even as it supports rich readings of the unsettling insights claimed for the writings. However, it offers a new kind of challenge: to read Dickens as if, consciously or not, he laid bare the tensions within himself in such a way as to reach the deep and typical anxieties of his own age – and ours, shaped as it is by its predecessors. This challenge was taken up by an influential American critic, Dorothy van Ghent, who found in the complex, non-realist development of character and plot in Dickens a vision linking inner and outer worlds which explains the strange, hallucinatory surface of his narrative. Her account of Great Expectations as the type of this approach towards Dickens has hardly been improved upon.

Activity 6

Read the extract ‘On Great Expectations’', from van Ghent's The English Novel: Form and function, in Part Two. This is a densely argued and detailed text, but I suggest that you focus on the following questions to enable you to identify the main points made. How does Dickens depart from the conventions of characterization and plot familiar from other novelists? In what way, then, does Pip's inner life become available to us? (Look at van Ghent's examples.) How does this explain his relationships with the main characters around him? Van Ghent goes on to assert that there are two main themes in Dickens's writing, which are also two related kinds of crime. How, if at all, are these themes resolved in this novel?

Discussion

Van Ghent claims that Dickens's writing is characterised by a ‘general principle of reciprocal changes, by which things have become as it were daemonically animated and people have been reduced to thing-like characteristics’ (Part Two, pp.247–8). Thus, Estella, ‘the star and jewel of Pip's great expectations … wears jewels in her hair and on her breast’, and says ‘I and the jewels … as if they were interchangeable’ (ibid., p.248). This is a device frequently used in fiction to illustrate symbolically a person's qualities, but in Dickens it becomes something more, since the objects seem to ‘devour and take over’ the person whose attributes they represent. Miss Havisham has used two children, Pip and Estella, as ‘inanimate instruments of revenge for her broken heart … and she is being changed retributively into a fungus’ (ibid.). She anticipates her end by referring to her relatives feeding off her when she is laid out on the same table as her decaying wedding-cake.

In addition to the reciprocal transformation of human and non-human in the Dickens world as a means of representing the inner life of his characters, the momentum of his plots is driven by moral imperatives rather than realistic events. They ‘obey a‘causal order – not of physical mechanics but of moral dynamics’ (ibid., p.249). What brings Magwitch across the oceans to Pip again is their long-standing guilt, ‘as binding as the convict's leg iron which is its recurrent symbol’ (ibid.), rather than any inherently logical plotting. Again unlike realist or (as van Ghent calls it) ‘naturalistic’ fiction, another strategy is to make the ‘opposed extremes’ of good and evil become part of a ‘spiritual continuum’ (ibid., p.250). They become aspects of each other and even of a single character – in this case, Pip. Pip's inner life is displayed by means of his fantasies, projected onto those around him. All the characters are, in some sense, aspects of Pip himself.

This means that what van Ghent identifies as the two kinds of crime in Dickens – ‘the crime of parent against child, and the calculated social crime’ – are ‘analogous’, or like each other (ibid.). Both involve treating persons as things: the crime of dehumanization. They are also ‘inherent in each other’ (ibid.), in that the corrupt will of the parent or parent-figure towards the child becomes part and parcel of the corruption of social authority: the good authority figure has become (was always potentially?) evil. The brutality exercised towards Magwitch in childhood by ‘society’ (see pp.342–3) is therefore to be understood as the same as that meted out to the young Pip. The permutations of this vision are so far-reaching that they go beyond any rational explanation. Van Ghent suggests that we are prompted to think of a solution beyond the logical, such as ‘original sin’, which indicates the need for ‘an act of redemption’ (Part Two, p.251). In Great Expectations this does take place, although it ‘could scarcely be anything but grotesque’. The redemption is anticipated by Mrs Joe's ‘humble propitiation of the beast Orlick’ (ibid., p.252), a moment that reappears as ‘Pip “bows down,” not to Joe Gargery, toward whom he has been privately and literally guilty, but to the wounded, hunted, shackled man, Magwitch, who has been guilty toward himself’ (ibid.).

3.4 Fantasies and desires

Whether or not you agree with this complex account, these ideas are worth thinking about. Following van Ghent, we could go on to read the novel in terms of Pip's fantasies of desire and revenge. For example, when his sister has been smashed down with a convict's leg-iron, he is ‘at first disposed to believe that I must have had some hand in the attack’. Although we know he has not (p.117), this can easily be read as a reflection of Pip's real, but unconscious because aggressive, feelings towards the one who brought him up ‘by hand’, and regularly applied ‘the Tickler’ to his frame. There is so much suppressed (and indeed actual) violence in the novel, hovering on the edge of everything that happens, that this kind of reading is surely persuasive? If at first it seems improbable, consider the point at which, many pages later, when Orlick tries to murder Pip in revenge for what he (rightly) gathers have been all Pip's attempts to have him sent away, the gloating brute tells him ‘It was you as did for your shrew sister … You done it; now you pays for it’ (p.421). The rational explanation offered is that it was Orlick's resentment and jealousy at Pip's preferment, and his beating by Joe, itself provoked at least in part by Mrs Joe (chapter XV), that led Orlick into trying to murder her. However, the non-rational, deep association of Pip with Orlick (and Orlick with the primeval ooze, see p.129) remains. This is confirmed by many little details, such as the suggestion that Orlick also desires Biddy, expressed by his ‘dancing’ (ibid.) at her which so annoys Pip, surely because it is also an expression of his feelings on a level he can only convey indirectly, if at all.

When it came to describing feelings of desire, Dickens was, of course, inhibited by contemporary prudery. This was especially strong in the case of cheap and accessible serial fiction, which could enter every home. He was obliged to be indirect, but this has its advantages. Estella is far from being one of Dickens's notoriously ‘legless’ angels, like Agnes in David Copperfield, although to begin with Estella's body is absent, or substituted by a star, confirming the cold distance implied by her name. When Pip first sees her at the ironically named Satis House, ‘her light came along the long dark passage like a star’ (p.58). Her disdain is reflected in remarks about Pip's commonness, and his ‘coarse’ hands – remarks that linger in his mind, since he keeps repeating them, and which to us evidently provoke in him both class and sexual yearning at once. That his deeper desires are not confined to himself is clarified by another of his visits to Satis House, when, after he has beaten the ‘pale young gentleman’ in the hidden garden, he finds Estella

waiting with the keys. But, she neither asked where I had been, nor why I had kept her waiting; and there was a bright flush upon her face, as though something had happened to delight her. Instead of going straight to the gate, too, she stepped back into the passage, and beckoned me.

‘Come here! You may kiss me, if you like.’

I kissed her cheek as she turned it to me. I think I would have gone through a great deal to kiss her cheek. But, I felt that the kiss was given to the coarse common boy as a piece of money might have been, and that it was worth nothing.

This is skilfully done, and it is developed as an undercurrent of implication by another fight, that between Joe and Orlick. This was provoked, as I have suggested, by Mrs Joe's interfering. ‘You'd be everybody's master, if you durst’ (p.112), says the journeyman, which leads to a ‘Ram-page’ on her part, and Mrs Joe dropping ‘insensible at the window’, but not without having ‘seen the fight first, I think’ (p.113). On one level, Mrs Joe is depicted as a virago whose bullying of her young brother and husband in some sense is supposed to make her ‘deserve’ being flattened by Orlick. On another level her behaviour is presented as the implied product of frustrated desire: her ‘square impregnable bib’ (p.8) may well have something to do with Joe's inability to come ‘to a stand’ (p.48). In other words, both of them are subject to barely understood inhibitions and maltreatment in the past (which in Joe's case is given in detail, see pp.45–6).

Perhaps too we eventually understand the frigidly self-consuming Miss Havisham as the product of her past, and Pip as deeply connected with both Joe and Miss Havisham in his secret sado-masochistic urges – secret in the sense that they are never openly acknowledged, while being present through implication. Miss Havisham and Orlick are both linked with Estella, the main object of Pip's desire, and also with his class guilt. It is fitting that he should be nearly killed by both of them towards the end, duly expressing the satisfaction of his need for self-punishment through the twin ordeals. All this may produce a feeling of inevitability, rather than surprise, when we learn that Estella marries the brutal Bentley Drummle, and that this leads to violence against her, too, before she can – in an analogous progression to Pip's – return to the main narrative, humbled and contrite.

Such hidden patternings begin to show what can be teased out of the richly ambiguous surface so well described by van Ghent, taking us beyond what appears at first sight to be merely another reflection of conventional mid-Victorian attitudes towards its restlessly aspiring heroes and its wayward women. Freudian readings like Wilson's and van Ghent's have multiplied, although today they are less common than they used to be. Their main message is that desire is interwoven with guilt along classic psychoanalytic lines, which propose that since desire is repressed it can only appear indirectly.

Let us take an example to illustrate this theory and its implications more fully. Until reading critics of this persuasion, I had been puzzled to know how to explain the fantasy Pip experiences at Satis House of Miss Havisham hanging by the neck from a great wooden beam, which he thought ‘a strange thing then, and I thought it a stranger thing long afterwards’ (p.63), and which recurs very much later (p.397). No explanation is offered. The only obvious connecting link seems to be the presence of Estella, whose appearance also comes to call up ‘strange’, hallucinatory feelings in Pip (p.235). It all feels too specific to be merely part of the deathly atmosphere surrounding Miss Havisham. An explanation is finally offered for the uncanny associations surrounding Estella when it is revealed that she has been reminding Pip of her mother, Molly, Jaggers's strong-wristed (and murderously violent) servant woman. This provides one last link of association, ‘wanting before’, and ‘riveted for me now, when I had passed by a chance, swift from Estella's name to the fingers with their knitting action, and the attentive eyes’ (p.386).

Does this help to explain the image of Miss Havisham hanging? Might there be a connection with Pip's early memory of Magwitch resembling a hanged man come to life and then going to hook himself up again? After all, it turns out that all these people are related, in one way or another, in the complicated unravelling of the plot. There are various possibilities here and I do not want to tie things down too much, since we are talking about hints and suggestions rather than anything very clear. However, if we think in terms of van Ghent's view that everything in Dickens's ‘nervous’ universe has in some way to do with child-parent relations, it seems possible to read things as follows. Pip's fancy of Miss Havisham hanging from the beam recalls his similar fancy of the escaped convict, because it thereby suggests the boy's unconscious wish to kill both his imagined parent–benefactors. This is a repressed desire that produces excessive feelings of guilt, fear and anger towards them, feelings that retrospectively become justified to the degree that both Magwitch and Miss Havisham are revealed as manipulators of their ‘adopted children’. These children inadvertently, that is unconsciously, contrive to punish them, and could even be said to bring about their deaths. When Pip imagines Miss Havisham hanging the second time – ‘A childish association revived with wonderful force’ (p.397) – he has just learned that Estella has married, and that Miss Havisham regrets what she has done. She asks for his forgiveness and, although according to the Christian moral scheme he must comply, there is a repressed desire to punish her, which is realised the next moment when she bursts into flames in his presence. Whether this is accidental or not is left unclear. Similarly, when the returned convict reveals his identity and his relationship as ‘second father’ (p.315) to Pip, the first impulse of revulsion becomes a much more extended attempt to rescue and forgive, but in vain, leaving Pip in the end safely alone.

I say ‘safely’ because Pip now refuses any kind of patronage, financial or familial, despite the advice of both Wemmick and Jaggers. Although at first this leaves him ill and alone, Joe comes to look after him ‘in the old unassertive protecting way’. ‘I fancied I was little Pip again’, he says, becoming ‘like a child in his hands’ (p.461). The new, patrilineal bonding enables Joe, the father who never was, to become father to another little Pip: ‘– I again!’ as Pip expresses it (p.475). All Pip's guilty fears and visions of murder can disappear at last in this recreation of himself, through his final acceptance of Joe and Biddy.

3.5 Summary

Like so many earlier scenes, this return to the forge replays numerous details of Pip's preceding encounters, giving it an almost ritualised feel, as the reader is made to go through the process of repetition and return that makes up the basic rhythm of the story. These details appear at first to be purely surface realism, but an active reader can sense that more lies behind or within them, in the heightened awareness encouraged by recognition of Dickens's hallucinatory writing. When Biddy touches the new Pip's hand to her lips, ‘and then put the good matronly hand with which she had touched it, into mine’ (p.476), we can understand that she thereby replaces Mrs Joe's bringing up ‘by hand’ and the sado-masochistic feelings long associated with it, with her own form of domesticated desire. Pip's hands were burnt by the false mother, Miss Havisham, and are now recovered. Before that, Magwitch had, in the climactic recognition scene, come towards him, ‘holding out both his hands for mine’ (p.327). Pip resisted this action at first, then accepted it, as he accepted his ties to the outcast convict. On the latter's deathbed he held Magwitch's hand, who finally ‘raised my hand to his lips. Then, he gently let it sink upon his breast again, with his own hands lying on it’ (p.455). That moment is recalled by ‘the friendly touch of the once insensible hand’ (p.477) of Estella when, at the last, Pip meets the convict's daughter and thinks of Magwitch pressing his hand, a memory empowering him to take ‘her hand in mine’ (p.479), as they go out of the ruined place in the last paragraph of the novel.

Thus, the constant association of Miss Havisham's world with that of Magwitch, represented as coincidence, contains a revelatory truth about Pip and the source of his aspirations. It is also an indication of their common status as outsiders.

4 Little Britain and the Empire

4.1 A changing society

Reading Great Expectations for its insights into the ways of the psyche does not mean that we should ignore its connections with its time or ours, or with the wider history of Britain in the world. As van Ghent pointed out, the intuition expressed in terms of Dickens's creation of a universe of reciprocal change, in which human and non-human become each other, took place at a time that witnessed

a full-scale demolition of traditional values … correlatively with the uprooting and dehumanization of men, women, and children by the millions – a process brought about by industrialization, colonial imperialism, and the exploitation of the human being as a ‘thing’ or an engine or a part of an engine capable of being used for profit. This was the ‘century of progress’ which ornamented its steam engines with iron arabesques of foliage … while the human engines of its welfare grovelled and bred in the foxholes described by Marx in his Capital.

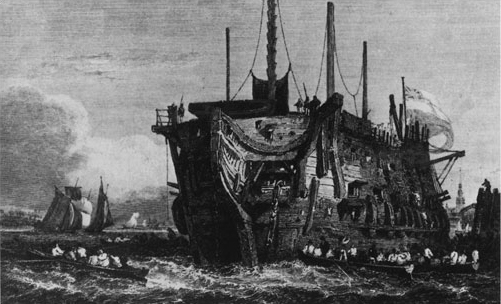

According to this view, the class system depicted in the novel, and the great expectations it feeds on, are ultimately rooted in the reality of the prison hulks (Figure 3), the decay and murder that occupy the more or less hidden underground of the narrative. The most pointed irony of Pip's story is that the woman he falls in love with, and perhaps in the end joins, turns out to be the child of that dark and hidden reality.

Reading the novel in terms of its power as social statement or critique goes back at least as far as the work of two key figures mentioned earlier, George Orwell and Humphry House. House in particular established an influential interpretation of Great Expectations based upon a profound understanding of the nature of mid-Victorian British society. ‘Many people’, he said, ‘still read Dickens for his records and criticism of social abuses, as if he were a great historian or a great reformer’ (The Dickens World, 1965 edn, p.9). He went on to question this view, since the precise connection between Dickens's writings and the times in which they appeared, between his urge for reform and some of the things he wanted reformed, was far from clear-cut. Moreover, the Dickens that emerged from House's account of the novels, the journalism, and from much contemporary comment on the social and political issues that interested the novelist – from debtors’ prisons to child labour, from prostitutes to sanitation, from schools to religion – was a relatively conservative figure. This Dickens drew attention to conditions after others had noticed them, and proposed reform rather than revolution, insofar as he proposed anything at all. In Orwell's words, Dickens's criticism of society ‘is almost exclusively moral … There is no clear sign that he wants the existing order to be overthrown, or that he believes it would make very much difference if it were overthrown’ (Inside the Whale, 1940, in Wall, Charles Dickens, 1970, pp.297–8).

Such perceptions of Dickens continue to occupy the middle ground of Dickens criticism. Whether or not we accept them, the account of Great Expectations offered by House still deserves attention for its informed judgement of the novel as an expression of the phase of society in which it was written (not the imaginary dates of its plot). House says:

In the last resort [Dickens] shared Magwitch's belief that money and education can make a ‘gentleman’, that birth and tradition count for little or nothing in the formation of style. The final wonder of Great Expectations is that in spite of all Pip's neglect of Joe and coldness towards Biddy and all the remorse and self-recrimination that they caused him, he is made to appear at the end of it all a really better person than he was at the beginning. It is a remarkable achievement to have kept the reader's sympathy throughout a snob's progress. The book is the clearest artistic triumph of the Victorian bourgeoisie on its own special ground. The expectations lose their greatness, and Pip is saved from the grosser dangers of wealth; but by the end he has gained a wider and deeper knowledge of life, he is less rough, better spoken, better read, better mannered; he has friends as various as Herbert Pocket, Jaggers, and Wemmick; he has earned in his business abroad enough to pay his debts, he has become third partner in a firm that ‘had a good name, and worked for its profits, and did very well’. Who is to say that these are not advantages? Certainly not Dickens.

Activity 7

What do you think of House's account of Great Expectations? Which elements in the book appear to confirm what he says, and which do not?

Discussion

I would suggest that House's account is plausible as far as it goes – which is not far enough. Dickens does appear to approve Pip's achievement of respectable middle-class integrity by the end of the novel, telling us that he has worked hard and paid his debts, unlike the ‘false’ gentleman, Compeyson, who resorted to crime and betrayal. Although he relies on unearned wealth, Pip is not like Miss Havisham's dubious relatives, who ‘sponge on others’. Mrs Pocket's delusions of aristocratic grandeur go hand in hand with an inability to do anything remotely resembling work. In particular, we are encouraged to approve of ‘the only good thing I had done, and the only completed thing I had done, since I was first apprised of my great expectations’ (p.411), namely, Pip's secret arrangement to help Herbert Pocket obtain a place in a commercial venture. Pip's life of wealthy idleness is certainly shown up when the transported convict reappears to claim him and his ‘genteel’ manners are fully demonstrated. When we witness the silly drunkenness and womanizing of The Finches of the Grove (p.269) and Pip's insensitive behaviour towards Joe and Biddy, it is perhaps an achievement on Dickens's part to have maintained our sympathy through ‘a snob's progress’.

Is that all it is? Pip is never merely a snob, although much of the comedy of the novel is drawn from the superficial side of his aspirations. For example, when Pip arrives to select a suit appropriate for a young gentleman with expectations, the tailor Trabb's boy knocks his broom ‘against all possible corners and obstacles, to express (as I understood it) equality with any blacksmith, alive or dead’ (p.148). He later parodies Pip's ‘distinguished’ walk through his home town, by walking alongside, airily waving his hand and exclaiming ‘Don't know yah!’ to the delight of the spectators and Pip's deep embarrassment (pp.242–3). Pip's snobbishness brings misery, however, and his own continuous commentary upon it reveals as much and more. We are never allowed to forget that at the centre of the narrative there is a narrator who does not excuse or disguise his earlier flaws. Moreover, by revealing the immense web of connections linking Pip's gentility on the one hand, and murder and deportation on the other, the narrative implies that the great achievements of mid-Victorian society were founded upon some very dark realities indeed.

4.2 Great Expectations and realism

House's reading relies upon assuming that the novel is a realist text, with a satirical edge. Yet it is a reading that can be taken further, and some critics have developed a much more complex and persuasive view of the theme of gentility.