Marketing in the 21st century

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 25 April 2024, 8:16 PM

Marketing in the 21st century

Introduction

Welcome to Marketing in the 21st century. This course briefly introduces you to the concept of marketing, how to assess if your organisation is marketing orientated and the role of ethics in marketing. You will then be introduced to the principles of branding before considering internal marketing in turbulent times. First let’s start by considering a quote from British entrepreneur Emma Harrison published in the British newspaper the Daily Mail (2004):

There are three things that you should spend your time doing: marketing, marketing, marketing. If you are not prepared to do that, then everything else is irrelevant.

As we shall see throughout this course, marketing encompasses a wide range of interrelated activities and at its heart, drives the organisation forward.

As a manager you will have had, to varying extents, some experience of marketing. This could be an involvement in making strategic decisions which have marketing implications. On the other hand, as a consumer you will have been exposed to marketing from an early age, possibly making you sceptical about what it can offer.

Marketing is concerned with satisfying customer needs but is it a positive activity for our societies?

Marketing encompasses a number of activities that are partially created by the organisation but also largely influenced by factors in the external environment such as competitors’ activities and legislation. As a management activity, marketing is constantly changing and evolving to meet the needs of the market. For many this constant change makes it an exciting profession, as summarised here by Ian Hunter, Head of Marketing at Fujitsu Services.

What excites me most about marketing?

Working in marketing means that you are in a privileged position, working across all parts of a business at all levels, for the good of the whole company. The excitement comes from many areas:

- working/influencing (challenging) executives on strategic direction

- implementing change – identifying new strategies and working with the company to implement the thinking

- intellectual challenge – thinking through complex organisational problems and developing strategies to support these

- working with smart people – because while the work is important to the company, you get to work with the smartest people (internally and externally)

- creativity – you are continually having to come up with new and innovative ways of doing things. Working in an innovative environment is fun and exciting.

What are the biggest challenges for marketing?

For the IT sector, it is how we respond to/make money from Cloud.

For marketing it is:

- being able to demonstrate the value marketing delivers

- exploiting/using social media to its full potential (to develop relationships).

What does marketing contribute?

Marketing is a process that everyone in the company is involved with (satisfying customer needs, at a profit). So everyone is in marketing!!

The marketing function must be configured to use appropriate skills and techniques to support this ambition and be able to demonstrate value. In a B2B environment this includes:

- increasing the customer’s predisposition to purchase – brand awareness, relationship events, thought leadership

- lead generation – thought leadership, direct marketing, etc.

- relationship creation – forums, social media, events

- evidence – case studies and references

- sales force training and development

- account development – account-based marketing

- market and customer insight.

This free course is an adapted extract from an Open University course BB844 Marketing in the 21st century

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

articulate whether marketing is a process or philosophy

think analytically, creatively and in an integrated manner about marketing ethics

define what a brand is and value of brands to organisations and consumers

understand how marketing practice is changing now and will change more in the future.

1 What is marketing?

Stop and reflect

How would you define marketing?

Exactly what constitutes marketing has kept academics busy for a long time, yet there is still no consensus. Why has it been so difficult? For some academics such as Halbert (1965), the reason is that marketing lacks any theoretical basis. In other words, the concepts, practices and ideas that form marketing lack any strict, coherent meaning.

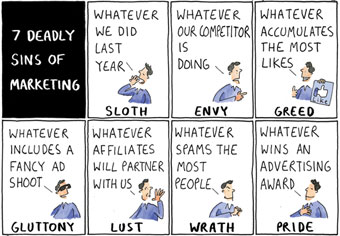

However, this has not prevented people from offering their own definitions, for example, as summarised in Figure 1.

This figure is in the form of a cartoon comprising four columns and two rows. In the top row the four columns from left to right are labelled7 Deadly Sins of Marketing, Sloth, Envy, and Greed. In the column labelled Sloth there is a drawing of a man saying ‘whatever we did last year’. In the column labelled Envy there is a drawing of a man saying ‘whatever our competitor is doing’. In the column labelled Greed there is a drawing of a man saying ‘whatever accumulates the most likes’. In the second row the four columns from left to right are labelled Gluttony, Lust, Wrath and Pride. In the column labelled Gluttony there is a drawing of a man saying ‘whatever includes a fancy ad shoot’. In the column labelled Lust there is a drawing of a man saying ‘whatever affiliates will partner with us’. In the column labelled Wrath there is a drawing of a man saying ‘whatever spams the most people’. In the column labelled Pride there is a drawing of a man saying ‘whatever wins an advertising award’.

While this cartoon, to some extent, summarises some aspects of what marketing is, we need a more comprehensive definition. Perhaps one of the most commonly used definitions belongs to the Chartered Institute of Marketing (CIM) in the UK. CIM (2012) defines marketing as:

The management process responsible for identifying, anticipating and satisfying customer requirements profitably.

The key terms in this definition, ‘identifying, anticipating and satisfying customer requirements profitably’, will feature throughout this course but they are worth reflecting on.

Marketing can be defined as satisfying customer requirements at a profit. Such a profit could be defined purely financially or in terms of social importance. For example, reducing the number of smokers could be seen as a social profit. Without a profit an organisation loses its reason for existence. Yet this existence is sustained by satisfying customer requirements. An organisation can only do this by identifying and anticipating what the customer wants.

1.1 Added value

Another definition of marketing that is worth considering is from the American Marketing Association (2007):

Marketing is the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large.

While this encapsulates many aspects of the CIM definition it introduces a new theme – value. Value in marketing refers to the benefit the customer receives from consuming a product compared to the cost of the product.

For example, purchasing a large flat screen television for £900 may represent a large financial outlay as well as the cost of time and effort spent researching and deciding on brand, product and technology. Related to this are the benefits the customer may receive from purchasing this television such as high definition, being able to watch 3D programmes, being the envy of their friends etc. If the benefits outweigh the cost, the purchase would have ‘added value’ for the customer.. In marketing, all organisations aim to deliver added value. The greater the added value, the more likely the organisation will be successful.

From a marketing perspective, added value is delivered from what is widely known as the ‘total market offering’. This means not only the benefits of the product itself but the organisation’s own brand and reputation. This will be determined by factors such as technological characteristics, distribution outlets, sales staff and other employees representing the organisation. The way all of these contrast (positively and negatively) with the organisation’s competitors will lead to the customer making a decision about their preference, for example, preferring a Bang and Olufsen television to one made by LG.

Stop and reflect

Take a few minutes to stop and reflect on what added value your organisation offers to its customers.

1.2 The marketing concept

What these two definitions have in common, along with others, is what is commonly referred to as the marketing concept. This is widely considered to consist of three components (McGee and Spiro, 1988):

- Marketing is customer orientated – it aims to satisfy customers’ needs and wants.

- Marketing is an organisation wide, coordinated activity which aims to deliver customer satisfaction. (We will explore this when we discuss marketing orientation.)

- Marketing is profit orientated rather than motivated by sales volume. (Note here that the concept of profit does not have to be financial but may represent a social outcome. For example, an anti-smoking advertisement that reduces the number of people smoking would be considered to have achieved a profit.)

1.3 Process and philosophy

A study by Crossier (1988) into providing a comprehensive definition of marketing analysed over 50 definitions and identified two broad themes:

- Marketing as a process

Marketing represents a process where an organisation ‘markets’ its products. This process consists of a number of activities which encourage the analysis of marketing opportunities, researching the market, deciding which segments to focus on and so on. From this perspective, marketing represents a structured and standardised approach to marketing management.

- Marketing as a philosophy

Marketing as a philosophy does not necessarily view marketing as a process but as a collection of underlying theories or principles. These place an emphasis on customer satisfaction etc. with perhaps the most important principle being marketing orientation. This refers to how an organisation reflects on, responds to and views its customers as being important to its existence. Viewing marketing as a philosophy encourages an organisation to view all its activities as a collection of principles or values that motivate it to satisfy its customers’ needs.

1.4 Exchange

We can also consider marketing as a process of exchange. In its simplest form, exchange in marketing represents the transfer of goods and money between two or more groups (these can be organisations purchasing supplies or customers such as a mother buying food for her baby).

However, Bagozzi (1975) adds that exchange within marketing is more complex and often more indirect than simply a customer exchanging money for a product from a supplier. He argues that it represents the interaction of a variety of intangible and symbolic meanings. For example, the symbolism attached to a brand such as Diesel clothing is likely to affect the marketing exchange between the customer and the supplier. How? A customer may value the status that owning Diesel clothing will be positively recognised and reinforced by their friends. A number of factors contribute to these intangible and symbolic meanings and these will form the basis for the remaining sections in this course.

1.5 Marketing orientation: trains, cars and bankruptcy

What happens to an organisation if it is not marketing orientated? Certainly history provides plenty of examples and one of these is the demise of the independent British car industry.

In the 1950s Britain was the world’s second biggest car producer. By 2005, MG Rover, Britain’s last independent car manufacturer, was declared bankrupt.

Critics pointed out that Britain’s car industry had produced the wrong cars, for the wrong markets and at the wrong price. Quite simply, the market found competitors’ product offerings more satisfying.

Another example of the importance of an entire industry being marketing orientated is the decline of train travel in the USA. In a classic marketing paper, Levitt (1960) argued that the decline of the American railways came about not necessarily because people did not want to travel by train, but because of the fundamental failure of the train companies to recognise their customers’ needs, i.e. convenience and comfort.

Levitt provides an example of how marketing orientation can work to great success: Henry Ford and his Model T car. When Henry Ford established the Ford Motor Company he recognised there was a massive, unmet demand for a cheap car.

This marketing opportunity was widely recognised by other manufacturers but they were unable to produce a car cheap enough to sell in large quantities. Hence no organisation was able to meet this demand.

Henry Ford, however, did not see the problem, only the marketing opportunity! He realised that if he could produce a car that sold for US$500 and make a profit from each one, he would be able to sell millions of cars.

By identifying the marketing opportunity, Henry Ford worked out a solution to meet this demand. The solution? Henry Ford invented the moving production line, ensuring he could produce his Ford Model T cheaply, en masse and sell it for US$500 at a profit.

1.6 Internal marketing

As well as ensuring marketing orientation, an organisation should also undertake internal marketing. Internal marketing views an organisation’s employees and their positions as customers and internal products. For example, a receptionist who represents the organisation when people call offers a product based on connecting the caller to the correct person (this is the receptionist’s internal product offering). As a customer the receptionist will expect to be provided with the correct contact information for everyone in the organisation so they can perform their product offering (their job) to the best of their ability.

Stop and reflect

Take a few minutes to reflect on how internal marketing affects you in your current job.

- Who are your customers?

- Are they external or internal?

Once you have identified who your customers are, think about how you deliver added value when you attempt to satisfy their needs. You should also ask yourself whether what you deliver is really of value to your customers.

How does internal marketing fit within marketing orientation? Marketing orientation argues that all employees of an organisation should undertake their job roles with the specific intention of maximising customer satisfaction. In the example of the receptionist, they are contributing towards the potential customer’s positive perception of the organisation and its product offering by handling their call effectively and efficiently.

Internal marketing aims to satisfy the needs of employees in their ability to undertake their job roles. Satisfied employees will be more able to offer a satisfactory service to existing and potential customers. Internal marketing, and consequently its contribution to achieving marketing orientation, consists of three objectives (Gronroos, 1981, 1985):

- overall – to have employees who are customer conscious, motivated and care orientated

- strategic – to create an organisational environment that supports customer awareness

- tactical – to sell the reasons for marketing efforts to all employees via staff training programmes as employees represent the face of the organisation.

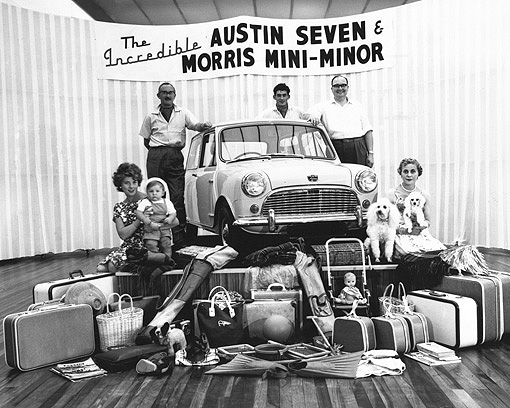

1.7 The Austin Seven

What happens if an organisation does not have internal marketing? A good example involves Austin Morris, the predecessor to MGRover, a British car manufacturer. This example is based on stories that have emerged from people involved in the car industry in the 1950s.

Like Henry Ford, Austin Morris identified an unmet customer demand in the market – the need for a compact, cheap, family car. The result was the launch of the Austin Seven (later called the Austin Mini) in 1959, which sold at a relatively low price of £537 (including taxes of £158). Although not an immediate success, it went on to become a mass selling car for Austin Morris.

The launch of the Austin Seven caught the attention of the competition, in particular the Ford Motor Company who also produced and sold cars in the UK. A story arising at the time of the launch involved a discussion between the President of Ford Britain and the Chair of Austin Morris in which the Ford President declared his disbelief that Austin Morris could be earning a profit from every Austin Seven it sold.

From Ford’s perspective, the car was simply priced too low to be financially viable. The Chair of Austin Morris protested strongly, arguing that its unique body structure and quick assembly process enabled Austin Morris to produce a profit. When asked what that profit margin was, he was unable to answer.

Fearing that Austin Morris had found a new way of producing low cost cars, the Ford President demanded that Ford engineers buy an Austin Seven car and calculate how much profit was being made per car. The Ford engineering team dismantled an Austin Seven, calculated the price of every individual component and reassembled it to calculate the cost of construction. The result? Ford calculated that the cost of producing each Austin Seven was far greater than the selling price. In other words, Austin Morris was making a loss on every Austin Seven it produced.

Why did Austin Morris allow this? The answer lies in the lack of internal marketing within Austin Morris. Apparently, the finance department had not worked out the financial cost of producing the car, believing the sales department’s assumption that it would produce a profit.

This assumption was based on what it thought the market would pay; if the price was wrong, surely the finance department would challenge it?

Internal marketing would have ensured that the departments involved worked to produce a car that not only satisfied customer needs but created a profit.

Needless to say, Ford’s President never raised the issue again.

Activity 1 Measuring marketing orientation

The purpose of this activity is to assess the extent to which your organisation is marketing orientated. It uses a questionnaire devised by Kohli et al. (1993) to measure marketing orientation levels in various organisations.

This activity gives you an opportunity to compare your organisation’s marketing orientation to the sample group used in Kohli et al.’s study. You will also be able to consider areas where your organisation may need to increase its marketing orientation.

In the first part of the activity you are asked to respond to 20 statements and indicate your level of agreement by using a Likert rating scale where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. For each statement click on the appropriate circle to move the orange line to the number that indicates your level of agreement.

This questionnaire was constructed using sound design principles. It uses a reverse technique so you cannot simply agree with all the statements. For this reason you may correctly disagree with some statements.

When you have responded to each statement, click on the Show Mean button. This will superimpose the scores for Kohli et al.’s sample group.

You should think about how your scores differ from those of the sample group. In some instances your scores may be very different – why? What is your organisation doing better and worse than those used in the study?

You can view help by clicking on the Help button or pressing the H key within the activity.

Now click on this thumbnail or View to access the questionnaire.

This interactive diagram consists of a range of questions, sequentially numbered. To the right of these questions are five circles. The far left circle is titled ‘Strongly disagree.’ The far right circle is titled ‘Strong agree.’ Running down the middle column of circles is a line. The activity asks you to click on the circle that indicates your agreement with the question. By clicking on the circle that indicates your agreement with the question, the line moves to that circle. Eventually be answering all the questions, the original straight line will move in various vertical ways across the screen, indicating the complete range of responses to the questions asked. A button then informs you that it should be pressed to show how your results compare to the original questionnaires sample group results. The diagram now shows a continuously running through line running down through the circles, representing the original sample group. You are now presented with two sets of lines. Your own line, representing your score to the questions. The line representing the original participants scores to the questions. The diagram allows you then to observe how your organisation scores against the original participant group in terms of marketing orientation. The questions asked in the diagram are as follows:

SECTION TITLE: Intelligence Generation

In this section, we meet with customers at least once a year to find out what products or services they will need in the future. In this business unit, we do a lot of in-house market research. We are slow to detect changes in our customers' product preferences. We poll end users at least once a year to assess the quality of our products and services. We are slow to detect fundamental shifts in our industry (e.g., competition, technology, regulation).We periodically review the likely effect of changes in our business envi-ronment (e.g., regulation) on customers.

SECTION TITLE: Intelligence Dissemination

We have interdepartmental meetings at least once a quarter to discuss market trends and developments. Marketing personnel in our business unit spend time discussing customers' future needs with other functional departments. When something important happens to a major customer of market, the whole business unit knows about it within a short period. Data on customer satisfaction are disseminated at all levels in this business unit on a regular basis. When one department finds out something important about competitors, it is slow to alert other departments.

SECTION TITLE: Responsiveness

It takes us forever to decide how to respond to our competitor's price changes. For one reason or another we tend to ignore changes in our customer's product or service needs. We periodically review our product development efforts to ensure that they are in line with what customers want. Several departments get together periodically to plan a response to changes taking place in our business environment. If a major competitor were to launch an intensive campaign targeted at our customers, we would implement a response immediately. The activities of the different departments in this business unit are well coordinated. Customer complaints fall on deaf ears in this business unit. Even if we came up with a great marketing plan, we probably would not be able to implement it in a timely fashion. When we find that customers would like us to modify a product of service, the departments involved make concerted efforts to do so.

Answer

This exercise should have shown you how your own organisation’s level of marketing orientation compares to a larger sample. You may have found that your organisation exceeds the sample average (congratulations) or that for some questions your organisation scored lower than the average. In this instance you should ask yourself what your organisation could do to address this problem.

2 Marketing and ethics

As a manager you may have to make decisions that raise ethical issues. Ethics is an important and growing consideration within marketing, from the perspective of both marketers and consumers.

The growth of fair trade and organic produce reflect customers’ willingness to spend more money for the same product if they perceive ethics have been applied to product sourcing.

Marketing ethics question whether particular marketing activities can be considered morally right or wrong. As you progress through this course, you should question your ethical position regarding the examples, concepts and activities you undertake.

Stop and reflect

Consider these marketing examples that raise ethical issues. To what extent are they acceptable to you and why?

- A manager gives an extra discount to a customer who is a personal friend.

- An organisation charges a higher price to less wealthy customers on the basis that they buy less from the organisation.

- A hospital or health insurance provider refuses to provide a drug to cancer patients on grounds of cost while neighbouring authorities provide it.

While some of these examples may be quite common, fairness is an issue because people are being treated differently purely on the basis of their power in relation to an organisation or its managers, or where they live. Fairness or justice is one of the key issues raised by ethics. Developing this perspective further, Marsden (2007) suggests that a consideration of marketing ethics should involve:

- recognising and describing moral issues that arise from marketing activities

- using ethical theories and frameworks to critically assess these moral issues

- establishing a set of codes, rules and standards for assessing what is right or wrong regarding the marketing activity being undertaken.

2.1 Ethics in practice

What does this mean in practice? Let us consider this case study.

Case study: BAE Systems and the sale of radar systems to the Tanzanian Government

[In 2010 BAE Systems, a military equipment producer, was taken to court regarding] a relatively small accounting offence admitted by BAE in relation to one contract in one country – a £28m radar deal in Tanzania in 2002.

A judge has declared he was “astonished” at claims that BAE Systems, Britain’s biggest arms firm, had not acted corruptly when its executives made illicit payments to land an export contract.

Mr Justice Bean said it was “naive in the extreme” to believe that a “shady” middleman who handed out the covert payments was simply a well-paid lobbyist.

The judge concluded that BAE had concealed the payments so that the middleman had free rein to give them “to such people as he thought fit” to secure the contract for the company. BAE did not want to know the details, he added.

Corruption allegations have swirled around the overpriced radar deal since it was signed in 2001, with former Labour [government] minister Clare Short saying: “It was always obvious that this useless project was corrupt.”

(Source: Adapted from Evans and Leigh, 2010)

Further information on the ethics of bribery can be found in the Guardian article ‘Bribery and disruption: British companies fuel corruption in Africa’ and the newspaper’s investigations into BAE Systems and bribery, The BAE files.

The first step identified by Marsden (2007), recognising and describing moral issues, can be applied to this example which raises a number of moral issues.

First, is BAE Systems right in paying the bribe or should it refuse to engage in purchasing negotiations on the basis that bribes are illegal and wrong? However, if not paying the bribe means that BAE Systems loses the contract, this may have wider implications for the organisation such as redundancies.

Another issue may be what its competitors are doing. If they are all willing to pay a bribe to get a contract, why should BAE Systems disadvantage itself by not paying it?

2.2 Ethical theories

The next step is to use ethical theories to understand these moral issues. An ethical theory is a systematic way of approaching ethical questions from a particular philosophical perspective. Western moral philosophy has developed a number of ethical approaches.

Three ethical theories are commonly used in the consideration of marketing ethics: utilitarianism, deontology and virtue ethics. Each may lead to a different conclusion when applied to the same ethical dilemma.

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism is concerned with the consequences of the decision. The quality of a marketing decision or action is assessed by looking at the consequences of implementing that decision. In deciding whether it is unethical the decision-maker will need to:

- assess the likely costs and benefits for each stakeholder

- make a decision based on what action produces the greatest benefit for all concerned.

This approach to ethical decision making is often used in public policy decisions where policy makers have to take the course of action that is likely to produce the greatest overall benefit for the greatest number of stakeholders (for example, all inhabitants of a region).

In our example, BAE Systems is faced with a dilemma. If it pays the bribe it wins the contract, ensuring the growth and survival of the organisation. However, paying it may be illegal and by doing so, BAE Systems perpetuates corruption in an African state that ultimately ensures its citizens suffer from misappropriation of their money. Yet not paying the bribe may result in redundancies and how would these affect employees’ families?

Deontology

Deontology is concerned not so much with the consequences of action but whether the underlying principles of a decision are right. According to this view ethically good decisions are made by adhering to key ethical principles such as honesty, truthfulness, respecting the rights of others, justice and so on.

Applying this theory to BAE Systems raises a number of issues. Bribery tends to be illegal so by paying a bribe BAE Systems makes everyone in the organisation indirectly implicit in an illegal act. Also if a bribe is paid, where does the money go? Does it reinforce the status of a corrupt section of the wealthy and avoid payment of taxes? In this example, a few people would benefit from the bribe to the detriment of the wider majority of Tanzanian citizens.

Virtue ethics

Virtue ethics views marketing ethics from the perspective of the moral integrity of the individual(s) involved in making the decision. A morally good decision is one that is based on the virtuous character of whoever is making the decision. Moral virtues include honesty, courage, friendship, mercy, loyalty and patience.

In our example, BAE Systems’ payment of the bribe lacks any virtue (effectively reinforcing corruption in Tanzania) and little courage (paying bribes may appear to be unofficial organisation policy).

It should be clear that making ethical judgements rarely involves clear decisions. Depending on the viewpoint, different ethical principles may well lead to different decisions. Often it is appropriate to look at an ethical question using different theories before making a decision.

Managers in public sector organisations will often have to make difficult decisions about which stakeholder needs to satisfy when limited budgets mean not all needs and expectations can be met fully. In many public sector and internal marketing contexts the customer or stakeholder has relatively little say over the kind of service they receive. Thus, questions of an unequal distribution of power are more acute in not-for-profit and internal marketing where one or both parties to an exchange are often locked into existing arrangements and cannot walk away if they are dissatisfied with what they are receiving.

Further information

Finally, if you feel that BAE Systems is in a difficult situation consider this news clip from Aljazeera. The outcome described in this clip raises serious ethical issues about the extent to which organisations can use their external environment to protect themselves.

If you are reading this course as an ebook, you can access this video here: Aljazeera on Britain's dropping of BAE Systems fraud inquiry

Having reached the end of this section you should be able to provide a good overview of what marketing offers an organisation and be able to indentify if your organisation is marketing focused.

By engaging with the market, organisations are exposed to situations and decisions that raise ethical issues. Often the correct ethical decision is not always apparent.

In conclusion marketing is about satisfying customer needs whilst making a profit.

A good example of an organisation that has consistently delivered added value to its products and customers and epitomises what marketing is, is Apple Inc. Watch this short video clip of Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple, introducing the first iPod. What is interesting is how he carefully describes the logic for his product and the added value it offers customers while eliminating direct competition. This is an example of a true marketing genius.

One factor that has contributed to Apple’s success is understanding exactly what its customers want. But how do we define a customer and how does it differ from a client or consumer? These questions are addressed in the next section.

When you are ready, please move on to Section 3 Brand Basics

3 Brand basics

Marketing requires an organisation to understand who is buying its products (customers, consumers or clients) and this is achieved through understanding customer motivations. Once customer needs are understood, the organisation will segment, target and position its products and itself in the market accordingly. Complementing this is the organisation’s need to achieve a competitive advantage and understand, predict and respond to environmental changes.

Once the organisation has achieved this, it then needs to consider how it applies its marketing strategy. One aspect of this is through branding.

The role and use of brands have been expanding over time. Initially brands were used to show ownership or the source of the product, as a guarantee of good quality and as a way to communicate with the marketplace. Today, brand development and management is a challenging and complex endeavour in a dynamic business world with increasingly sophisticated media.

In this section we will address briefly the origins of brands, define what a brand is and refer to the relevance and value of brands to organisations and consumers.

3.1 The origin of brands

Brands have a long history, with their origins traced back to marks or seals that were used to specify the ownership or origin of a product. For example, in 5000 BC men drew animals in caves, giving them symbols to identify their owners (McKinny Engineering Library, 2012).

By the end of the 19th century, the industrial revolution had brought an abundance and variety of organisations and products. With the emergence of competition it became increasingly important for producers to differentiate their products in the market. Consequently producers started attributing brand names to their goods to increase their consumer appeal (British Brand Group, 2012). For example, William Lever (founder of Lever Bros) made soap an attractive product for general consumption by naming it ‘Sunlight’ and packaging it in small pieces.

Brands became a way to communicate with consumers in the marketplace. The proliferation of self-service in the 1950s intensified the communicating role of the brand. It was important to have an appealing and distinct product that would stand out on the shop shelves. Complementing this, growing television ownership combined with increasing consumer sophistication resulted in the need for brand communications to become more pervasive and more complex.

For example, consider these three television advertisements for Coca-Cola from 1955, the 1980s and 2012:

Notice how the first advertisement focuses on the product and its characteristics as a refreshing and energising beverage, great for a break. In the 1980s advertisement, although the product is still important, the focus is more on youth pop culture, dance and happiness. You see much less about the product’s characteristics. The final advertisement shows Coca-Cola as a global brand, highlighting its presence in worldwide events such as the Olympics.

Today’s brands exist in all forms and shapes. They include product brands (e.g. Coca-Cola, Avon and Adidas), services brands (e.g. Pizza Hut and Allianz), company brands (e.g. SAP and IBM) and even virtual brands (e.g. eBay, Google).

This expansion took brands from a sign of ownership and guarantee of good quality to a way of communicating with the marketplace, making the role and use of brands core to the organisation’s marketing efforts.

3.2 Defining what a brand is

The word ‘brand’ originates from the old Norse word brandr meaning ‘to burn’. It referred to the mark that cowboys would burn into their livestock’s skin to identify the owner (Keller, 2008).

The term ‘brand’ was transferred and applied to business brands and is now widely used in business jargon. The American Marketing Association (AMA, 2012) defines a brand as a:

Name, term, design, symbol, or any other feature that identifies one seller's good or service as distinct from those of other sellers. The legal term for brand is trademark. A brand may identify one item, a family of items or all items of that seller. If used for the organisation as a whole, the preferred term is trade name.

The AMA brand definition highlights the idea of identifying the product and making it distinctive. It also suggests the different levels of application of brands: single items, family of items or even the organisation. We will consider this idea later in the course when we address brand hierarchy.

In principle, a brand is created when a marketer attaches a name or symbol to a product (Keller, 2008). Yet, in practice, and from a managerial point of view, brand management is much broader.

Brand management entails forming core bridges with the marketplace around awareness, image and reputation. Consequently, the term ‘brand’ also considers aspects related to the marketplace and customers’ perception of the brand. To capture this idea, the AMA (2012) considers the term ‘brand’ with a capital ‘B’ to define Brand and Branding:

A brand is a customer experience represented by a collection of images and ideas; often, it refers to a symbol such as a name, logo, slogan, and design scheme. Brand recognition and other reactions are created by the accumulation of experiences with the specific product or service, both directly relating to its use, and through the influence of advertising, design, and media commentary. A brand often includes an explicit logo, fonts, color schemes, symbols, sound which may be developed to represent implicit values, ideas, and even personality.

The AMA brand descriptions are evident in virtually all the brands to which we are exposed. Yet some brands are more appealing to us than others. Why?

The answer is complex, as we will discover throughout this course. For example, the car manufacturer BMW has its own YouTube channel showing its executives discussing how they translate the BMW brand into car designs and marketing communications to create an emotional link between the brand and consumer.

We can understand this brand relationship further through this video clip that discusses how emotions and experience are connected to the BMW brand features of efficiency and reliability.

We can illustrate how BMW communicates its brand offering in this BMW 3 series advertisement.

You may notice that the brand facets of innovativeness, reliability and consumer experience are reflected in the advertisement. The underlying idea behind the BMW 3 series is to convey sportiness and passion coupled with efficiency and impressive design.

In this example, the BMW brand helps managers to define their business and product offering, allowing them to connect with the market. Brands are not only relevant to organisations but they also help consumers make product choices. By looking at the BMW 3 Series advertisement the consumer expects a reliable and sporty car.

Stop and reflect

- Why do brands exist?

- Why are they important?

Think about your organisation and the brand(s) it sells. You may think that its brand(s) allow(s) your organisation to focus on higher quality standards and differentiate from cheaper offers in the market. You may also consider the extent to which the brand(s) is(are) relevant to conveying an image of quality to customers.

Alternatively, think of yourself as a brand consumer. Reflect on what makes you choose one brand instead of another. You may drive a particular car brand or wear certain branded clothes because they make you feel secure and important. You may also consider how often you tend to buy the same brand. Such brand repetition shows your loyalty towards a particular brand.

In the next three sections you will learn more about the benefits of brands to organisations and consumers. This will allow you to understand better the different roles that brands may have for businesses and customers.

3.3 The relevance of brands to organisations

Organisations may benefit from brands in different ways. Brands may be seen as important tools for connecting with the market but they are also a relevant managerial instrument. Using the example of Disney, the benefits of brands (Keller, 2008; Ellwood, 2002) for organisations can be summarised as:

- Connecting the organisation to the marketplace

Brands are a singular and unique differentiator of the organisation’s offering and constitute a powerful way to communicate with the marketplace. The unique meaning associated with a brand may instil certain customer responses such as loyalty and positive associations such as high quality or high performance. For example, the Disney brand instils customer loyalty and excitement.

- Driving the business

The brand and its purpose help to define the business. Many managers use brands to define their business and shape their activities. Ultimately the brand is a key strategic tool and asset through which the organisation can differentiate itself from competitors, resulting in increased competitive advantage and generating financial value. For example, quality, creativity and great storytelling are core drivers of the Disney brand.

- Shaping the internal culture

Deriving from the previous benefits, brands may help to shape the organisation’s culture and, ultimately, employees’ behaviours. Clearly specifying what the brand stands for and its proposition in the marketplace helps managers and employees undertake work that contributes to supporting the brand and the organisation. Working at Disney stands for excitement and creativeness.

- Attracting the best employees

Brands stimulate employee attraction and retention. Strong brands allow organisations to attract the best employees and retain them. People are proud to work in organisations associated with strong brands such as Disney.

- Leveraging business performance

Brands drive business performance since satisfied and loyal customers are more willing to pay a premium price for a trusted brand. Loyal customers also need less marketing expenditure and give positive word of mouth. Indeed, positive brand associations and customer loyalty are known to contribute to better levels of business performance. Ultimately customer loyalty impacts on sales and, consequently, on business survival. Disney benefits from a solid base of loyal consumers who continuously buy its products.

- Providing legal protection

Brands also offer an organisation legal protection over what it produces, through registered trademarks, patents and copyrights, and so contribute to the organisation’s competitive advantage. In product packages the trademark and the symbol ® are often seen. Some examples of Disney trademarks are Walt Disney World® Resort in Florida, Disneyland® Resort in California and Disney Cruise Line®.

3.4 Embracing brand benefits

Next we explore in more detail how Disney embraces the brand benefits. You will see how the Disney brand is an asset, serving as a source of business guidance, shaping internal culture and instilling customer loyalty by delivering an unforgettable customer experience. Such practices distinguish the brand from competing brands, giving it a solid position in the market.

Case study: the Disney brand

The Walt Disney Company, together with its subsidiaries and affiliates, is a leading diversified international family entertainment and media enterprise with five business segments:

- media networks

- parks and resorts

- studio entertainment

- consumer products

- interactive media.

The Disney brand stands for consistently delivering ‘quality, creativity and great storytelling’ (Interbrand, 2012).

The Disney brand as business guidance

The Disney brand is central to the business. The brand and what it stands for provide important business guidance and focus. The definition of the Disney brand is a compass for managers to make decisions aligned with the company’s strategic priorities:

Creating high-quality family content, making experiences more memorable and accessible through innovative technology, and growing internationally.

(Source: The Walt Disney Company, 2011, p. 1)

Attracting the right employees and shaping internal culture

As a consumer brand the word Disney is invaluable in attracting the right kind of employees who love the brand and want to contribute to its legacy. Therefore the brand is reflected in recruitment practices which try to match the potential employee, the brand and the experience it provides. For example, in a recruitment advertisement for cast members (employees) for Disneyland Paris you may read:

Could you imagine being able to wear the beautiful costumes from the wonderful world of Disney or even be part of the magic of our parades and shows? We offer you an exclusive invitation to make these dreams come true and see the magical sparkle in our guests’ eyes, all this thanks to you and your talents, whatever they may be…

(Source: Disney, 2012c)

Employees receive training about the brand and its overall promise i.e. what it stands for. Employees ‘practise’ the brand and their motivation is key to the brand performance. They are compelled to consider the effect that their actions and decisions may have on the brand.

The company culture is aligned with the brand promise. That is, it is aligned with the unique aspects that differentiate the brand. The company characterises its culture as entailing:

- Innovation

Commitment to a tradition of innovation and technology

- Quality

Striving to set a high standard of excellence and maintaining high-quality standards across all product categories

- Storytelling

Timeless and engaging stories to delight and inspire

Connecting to the market through customer experience and loyalty

Disney works hard to sustain lifelong relationships with customers, continually expanding product and service offerings and maintaining its brand consistency. In particular, Disney aims to build a strong base of loyal customers.

The key to brand loyalty is to understand the emotional connection that customers have with the brands and products they love and then respecting and cultivating that connection. One way to achieve customer loyalty is through the employees at Disney’s theme parks where the company offers unique destinations built around storytelling and immersive experiences for family entertainment. These theme parks are located around the world (e.g. in the USA, Europe and Asia). Walt Disney (the founder of Disney Inc.) determined from the start that, in the theme park, people would be treated not just as paying customers but as ‘guests in our own home’.

Walt Disney understood that if guests knew and believed that everyone in the organisation cared about them and their business, they would be loyal to Disney forever. Consequently, Disney theme park employees are empowered to create spontaneous magical moments for guests. Some of these are orchestrated and executed on a daily basis. The magical moments are supported by different programmes/actions such as guest of the day, honorary badges and titles.

For Disney employees the guest experience is most important. Positive interactions delivered consistently and sincerely (to show authenticity) on a personal level result in lasting memories and an emotional connection to the brand.

Stop and reflect

Often organisations assimilate the brand benefits in different ways, sometimes underestimating the brand’s potential. For example, a small organisation may essentially consider its brand as legal protection and overlook some of the other benefits such as product and overall offering differentiation.

Consider your organisation’s brand(s).

- What type of benefits do brands have for your organisation?

- How can those and other benefits be developed?

You may have recognised that the Disney brand is not defined by its products (e.g. theme parks, television channels, etc.) but in terms of customer experiences. This connection of the brand to the market is an essential part of branding. In the next section we will look at the benefits that brands may have for consumers.

3.5 The relevance of brands to consumers

There is a strong interaction between brands and consumers. We all buy particular brands and, for some products, we have a brand preference. It is in the interests then of an organisation to enhance the relevance of their brands to consumers and the wider market. To achieve this, organisations need to understand how brands are relevant to consumers.

We can illustrate the relevance of brands to consumers and how organisations manipulate this to increase their market share through the example of the sportswear brand Reebok®. By the early 21st century Reebok® sports trainers were losing market share to Nike and levels of customer loyalty were low. Its brand image was further harmed by selling the brand’s running shoes at low prices in supermarkets.

We will now look at some insights into why consumers seek out brand relevance, using the Reebok® brand as an example.

Easier identification

Brands help consumers to identify the products/producers they like, simplifying the buying process and reducing the perception of risk in buying a new product (Berthon et al., 1999; Berry, 2000).

When buying sports shoes, you can identify easily the Reebok® brand and distinguish it from any other sports brand by its unique logo. This identification provides consumers with the quality guarantee of the product and helps them make securer purchasing choices.

Brands as individual expression

Consumers often identify themselves with the symbolic meanings of a brand and develop a bond with certain brands that express their personality, self-image and beliefs. By consuming certain types of products/brands consumers convey who they would like to be, contributing to their self-identity (Ellwood, 2002; Keller, 2003). For example, consumers may buy organic food to show they care for the environment and animal rights. Organisations underline this by clearly stating such aspects in the definition of their brands.

Reebok® tackled its problems through a branding agreement with the rap artist 50 Cent, producing a range of fashion trainers using 50 Cent’s branded clothing range – G-Unit. The rationale was to encourage 50 Cent’s teenage fans to purchase G-Unit branded trainers made by Reebok®, as shown here with 50 Cent:

This Reebok® advertisement features 50 Cent enticing teenagers to consume the G-Unit branded trainers. Note how the desired consumer identity and identification with the brand are personified in the rap artist:

If you are reading this course as an ebook, you can access this video here: 50 Cent Reebok G-Unit Advert

If consumers use brands to create their own sense of self-identity, it follows that consumers will use brands to distinguish themselves from other individuals. Part of prevalent culture is that we are all individuals and through consumption we express our individuality (Fog et al., 2010).

You can see this individuality reflected in this Reebok® advertisement that uses the line ‘I am what I am’ while focusing on the individual, his personal aspirations and reality:

If you are reading this course as an ebook, you can access this video here: Reebok AD 2012 - (I Am What I Am)

Brands as social expression

Very often, to be part of a social group, consumers need to share the attitudes and beliefs of that group and, ultimately, seek allegiance by consuming brands that the group likes. The symbolic meaning of a brand is affected by the social group with which the consumer interacts (de Chernatony et al., 2011).

In this Reebok® advertisement the brand becomes the stage for social interaction. With a common interest in fitness, people get together and create a sports community that allows them to integrate in this social setting.

If you are reading this course as an ebook, you can access this video here: Reebok CrossFit: The Community

Stop and reflect

- What other benefits do you think brands may have for consumers?

You may think about aspects such as cultural expressions that come from brands. For example, brands being reflected in pop art by artists like Andy Warhol and his Campbell Soup cans.

From analysing the relevance of brands, you should now understand why it is important to manage a brand properly. In fact, as we noted in the introduction to this course, brands are valuable intangible assets. The example given earlier of how Coca-Cola outperforms its competitors in terms of brand asset values illustrates brand relevance. The underlying principle is that a branded product performs better in the market, and thus will have a positive financial impact on the organisation.

To address this idea of brands as assets and their favourable impact on business performance, marketers borrowed the notion of ‘equity’ from finance. In branding terms we refer to ‘brand equity’. In the next section we explore this concept in more detail.

3.6 Brand equity

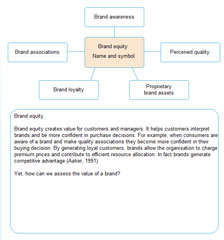

Aaker (1991, p. 15) defines brand equity as:

the set of brand assets and liabilities linked to a brand, its name and symbol, that add to or subtract from the value provided by a product or a service to a firm and/or to that firm’s customers.

A core aspect of brand equity relates to the name/symbol. In fact one of the first identification aspects of a brand is its name or symbol. The dimensions of equity revolve around the brand name and symbol, as shown in Figure 9.

This figure shows five elements Brand Awareness, Perceived Quality, Proprietary Brand Assets, Brand Loyalty and Brand Associations arranged in a loop around a central element labelled Brand Equity name and symbol. The central element is linked to the surrounding elements by lines.

Starting with the top element and going in a clockwise direction, the following text is revealed.

Brand Awareness

Brand awareness relates to the level of consumer awareness regarding the existence of a particular brand. When consumers think about soft drinks which brands do they recall? Coca-Cola and Pepsi have strong brand awareness in this market.

Perceived quality

Quality level is an association that consumers attach to a brand. When the market perceives a brand as being high quality, organisations avoid competing on the basis of price and may adopt premium pricing strategies. For example, Rolls Royce is highly regarded for its quality and reliability.

Proprietary brand assets

Proprietary brand assets, which are normally legally protected, include patents, channel relationships and trademarks that are attached to the brand. In high technology products, brand innovation may lie in protecting product/technology patents and licensing. For example, there have been legal issues between Apple and Samsung regarding aspects related to their brands.

Apple contends Samsung’s Galaxi Tab 10.1 is too similar in terms of design to its iPad and Samsung considers Apple infringed its 3G patents. Both companies have made legal complaints in various countries including Australia, Germany and The Netherlands.

Proprietary assets also include aspects such as brand symbols (e.g. logo) and the brand name. PepsiCo, Inc. has clear guidelines for the use of trademarks, names, titles, logos, images, designs, copyrights and other proprietary materials. All these objects are copyrighted and can only be used for commercial purposes with the company’s agreement.

Brand loyalty

Brand loyalty refers to consumers who repeatedly buy the same brand. Having loyal customers enhances brand visibility and allows organisations to save resources in attracting new customers.

It further pressurises retailers to make these brands available to customers. For example, online retailer Amazon has a loyalty programme (Amazon Prime) offering benefits to customers who join as a way of building customer loyalty.

Brand associations

Marketers try to attach positive and strong associations to the brand such as lifestyle and personality. For example, the Ritz Hotel in London is associated with luxury and sophistication.

End description.

Brand equity affects profitability (Stahl et al., 2012) and the organisation’s overall performance. For example, when consumers associate quality with a specific brand, they are more likely to purchase it.

In addition, by encouraging brand loyalty, organisations are able to charge premium prices and, ultimately, such brands have higher financial values and impact on overall performance.

Stop and reflect

How would you define and assess your organisation’s brand equity from the perspective of:

- brand awareness

- brand loyalty

- brand associations

- perceived quality

- proprietary brand assets?

When you are ready, please move on to the final section – International marketing in turbulent times

4 International marketing in turbulent times

In this final section we consider the challenges of international marketing and; how current economic conditions are problematic for international marketing. In particular:

- how price competition leads to lower quality, and

- indifference from the customer.

This is discussed in a podcast that introduces the topic of the challenges of international marketing. Specifically, Albrecht’s (2006) reference to the growing internationalisation of Chinese organisations and Goldsmith’s (2004) trend of increasing globalisation are reviewed.

Before you listen to the podcast it is important to provide a brief overview of some of the environmental factors that may affect organisations in a globalising market.

Specifically, an organisation should ask itself these questions:

- What are the levels and type of competition that exist in foreign markets?

- How will they respond to the market entry of a new competitor?

- To what extent can the organisation quickly and efficiently change from being a domestic orientated organisation to an international one?

Once the organisation has answered these questions, it should undertake an international PESTLE analysis. Themes that it may wish to explore in deciding which markets to enter may include:

Political

- To what extent does the political system in other countries actively encourage competition from foreign organisations?

- What international and domestic laws do other countries adhere to and are these free from political interference?

- Is the foreign market a member of any international trading groups, such as the World Trade Organisation or the European Union? If so, to what extent will this benefit the organisation?

- What are the historical connections between the countries identified and the organisation’s own? If there is a connection, is this a positive or negative one? What are the implications of these connections?

Economic

- How would foreign exchange fluctuations affect the organisation’s decision to enter a foreign market? For example, China has a relatively fixed exchange rate, unlike that of the USA, which is determined by market forces.

- What is the level of disposable incomes and how is this spread across the social strata? For example, in Japan disposable incomes are high but the Japanese have recently favoured saving their money rather than spending it on consumer goods. In the USA, high levels of disposable income appear to be biased towards higher earners, with low earners using their money to buy necessities.

- What is the level of new industrial growth in the desired foreign markets? For example, while China continues to experience rapid economic growth, the African and Indian sub-continents are expected to develop economically in the next decade.

Sociological

- How do cultural, ethnic, religious and societal values differ from those of the organisation’s country?

- Is the organisation able and willing to accommodate these differences in its marketing?

Technological

- To what extent will the organisation’s patents, intellectual property and copyrights be protected in international markets? For example, although China, under its membership of the World Trade Organisation, is obliged to stop the production of copied/fake products, this has not prevented numerous Western organisations from accusing Chinese organisations of blatant copying.

- Does the organisation’s technology conform to local laws? For example, electrical items that run on non-domestic currents could be dangerous.

- What is the current level of technology offered in products in international markets? For example, Renault cars of France bought the Romanian car manufacturer, Dacia to gain entry into international markets that want a low-priced car. Dacia achieves this low cost by offering cars that lack the modern technologies of mainstream cars sold in Western markets.

Legal

- Consumer laws differ between countries and international marketers need to be aware of this. For example, descriptions of products’ benefits may be affected by trade description law.

- Competition laws regarding how organisations can compete differ. For example, in the USA advertising is allowed to discredit competitor products directly, while in Europe this activity is often illegal.

Environmental

- How are climate differences likely to affect the performance of the organisation’s products? Are its products suitable for consumers in extreme examples of heat and cold?

- Are its products likely to be affected by countries that operate punitive taxes against those organisations that produce large amounts of carbon?

Perhaps two of the biggest international challenges facing the international marketer in the first part of the 21st century have been the opportunities and threats raised by China’s increasing economic power, and the financial crisis that at the time of writing (2013), continued to cripple the Eurozone countries.

Now listen to Adrian Lindridge’s podcast in which he discusses his experiences of establishing the European operations for a Chinese company and the wider marketing implications of doing business in both China and Europe.

Transcript

Stop and reflect

- To what extent has your organisation been immune to the wider international economic environment?

- Has it been able to be truly independent of economic events occurring in other countries?

Even if your organisation has no overseas markets, it is still likely to be affected by international economic problems. You should consider the extent to which your organisation can protect itself from the international economic environment, if at all.

Conclusion

In this course you have engaged in a sample of the key issues affecting marketing in the 21st Century. You considered if marketing was a process or philosophy, the role of ethics in marketing and how sometimes ethical decisions may not always be apparent.

You then considered the role of branding in marketing and personal identity and finally we briefly considered one of the influences on how marketing practice is changing.

We hope that you found this course interesting and that it has encouraged you to continue studying marketing.

Glossary

- Brand

- A name term, design, symbol or any other feature that identifies one seller's good or service as distinct from those of other sellers.

- Brand associations

- Marketers try to attach positive and strong associations to the brand, such as lifestyle and personality.

- Brand awareness

- The consumer's ability to identify a manufacturer's or retailer's brand in sufficient detail to distinguish it from other brands.

- Brand equity

- The marketing and financial value associated with a brand's strength in a market, which is a function of the goodwill and positive brand recognition built up over time, underpinning the brand's sales volumes and financial returns.

- Brand image

- The perception of a brand in the minds of persons. The brand image is a mirror reflection (though perhaps inaccurate) of the brand personality or product being. It is what people believe about a brand-their thoughts, feelings, expectations.

- Brand loyalty

- A strongly motivated and long-standing decision to purchase a particular product or service.

- Brand preference

- One of the indicators of the strength of a brand in the hearts and minds of customers, brand preference represents which brands are preferred under assumptions of equality in price and availability.

- Competitive advantage

- The achievement of superior performance vis-à-vis rivals, through differentiation to create distinctive product appeal or brand identity; through providing customer value and achieving the lowest delivered cost; or by focusing on narrowly scoped product categories or market niches so as to be viewed as a leading specialist.

- Consumer

- Traditionally, the ultimate user or consumer of goods, ideas, and services. However, the term also is used to imply the buyer or decision maker as well as the ultimate consumer. A mother buying cereal for consumption by a small child is often called the consumer although she may not be the ultimate user.

- Exchange

- The act of giving a one thing in exchange for another. In marketing this typically represents a product being exchanged for money.

- External environment

- A range of conditions, events and occurrences that are outside of the organisation, and often outside of their control. For example, a country's economic performance is likely to affect the trading conditions of the organisation.

- Internal marketing

- Internal marketing views an organisation’s employees and their positions as customers and internal products.

- Marketing opportunities

- A previously unidentified demand, need or want within the market that the organisation can exploit before its competitors do so.

- Marketing orientation

- A marketing-oriented organisation devotes resources to understanding the needs and buying behaviour of customers, competitors’ activities and strategies, and of market trends and external forces – now and as they may shape up in the future; inter functional coordination ensures that the organisation’s activities and capabilities are aligned to this marketing intelligence.

- Perceived quality

- Quality level is an association that consumers attach to a brand.

- Perceived quality

- Quality level is an association that consumers attach to a brand.

- Product

- A bundle of attributes (features, functions, benefits, and uses) capable of exchange or use; usually a mix of tangible and intangible forms. Thus a product may be an idea, a physical entity (a good), or a service, or any combination of the three. It exists for the purpose of exchange in the satisfaction of individual and organisational objectives.

- Proprietary brand assets

- Include: patents, channel relationships and trademarks that are attached to the brand, and are usually legally protected.

- Trademark

- Legal designation indicating that the owner has exclusive use of a brand.

References

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Dr Andrew Lindridge and Dr Claudia Simoes.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Cover image ChrisGampat in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Licence.

For the avoidance of doubt, all videos are viewed in YouTube (via embedded links) and subject to YouTube’s terms and conditions.

Figure 1

Fishburne, T. (2011), 7 Deadly Sins of Marketing, © Marketoonist.com

Figure 2

1919 Ford Model T Touring, © Car Culture ® Collection/Getty Image

Figure 3

Austin Seven Display, © R. Viner/Stringer, Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Figure 4

© Victor Correia/shutterstock.com

Figure 5

© BMW Group. With kind permission

Figure 6 (left)

© iStockphoto.com/@ Andrea Zanchi

Figure 6 (right)

© iStockphoto.com/GYI NSEA

Figure 8

Matt Baron/BEI/Rex Features

Activity 1 (questionnaire) Measuring marketing orientation

Kohli, A.K., Jaworski, J.B. and Kumar, A. (1993) ‘MARKOR: A measure of market orientation’, Journal of Marketing Research, November, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 467–77. American Marketing Association. Reprinted with permission from Journal of Marketing Research, published by the American Marketing Association.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University