Imagination: the missing mystery of philosophy

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 25 April 2024, 9:25 PM

Imagination: the missing mystery of philosophy

Introduction

This course investigates certain philosophical issues concerning imagination, creativity and the relationships between them, and considers the conceptions and varieties of imaginative experience.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 3 study in Arts and Humanities.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

discuss basic philosophical questions concerning the imagination

understand problems concerning the imagination and discuss them in a philosophical way.

1 Imagination

Imagination, a licentious and vagrant faculty, unsusceptible of limitations and impatient of restraint, has always endeavoured to baffle the logician, to perplex the confines of distinction, and burst the enclosures of regularity.

(Samuel Johnson, Rambler, no. 125, 28 May 1751)

In much of western thought, the imagination has an ambiguous status, seemingly poised between spirit and nature, mediating between mind and body – the mental and the physical – and interceding between one soul and another. For Aristotle, the imagination – or phantasia – was a kind of bridge between sensation and thought, supplying the images or ‘phantasms’ without which thought could not occur. Descartes argued that the imagination was not an essential part of the mind, since it dealt with images in the brain whose existence – unlike that of the mind – could be doubted. Kant, on the other hand, held that the imagination was fundamental to the human mind, not only bringing together our sensory and intellectual faculties but also acting in creative ways, a conception that was to blossom in Romanticism and find poetic expression in the works of Coleridge and Wordsworth. More recently, the role of the imagination in empathy has been stressed: the ability to identify with our fellow human beings and with fictional characters being regarded as crucial in accessing other minds, enriching our own experience and developing our moral sense. In fact, in the history of western thought, the imagination has been seen as performing such a wide range of different functions that it is problematic whether it can be understood as a single faculty at all. In imagination we are able to think of what is absent, unreal or even absurd, and so it appears to grant us almost unlimited conceptual powers. Yet it also seems to inform our perception of what is present and real and everyday, and so permeates the most basic levels of our daily lives. In this course, we will be concerned with some of the different ways in which the imagination is talked of and conceived, exploring just what the imagination might be and what philosophical issues it raises.

The course is divided into two main sections. In the first, we will look at the range of conceptions of imagination, address the question of whether ‘imagining’ can be defined in any useful way, and consider the implications of this for a philosophical understanding of imagination. Despite the important role that is often accorded to the imagination in our mental activities, the topic has been somewhat marginalised in the philosophical literature, particularly (and perhaps surprisingly) in contemporary philosophy of mind. This has led one writer to call imagination the ‘missing mystery’ of philosophy, and in this course I will say something about what this mystery is meant to be, and how one might go about ‘demystifying’ the imagination. In the second main section, we will examine the relationship that imagination has to imagery and supposition, both of which have been seen as closely connected to, and sometimes even identified with, imagination. I will end with a review of the discussion.

2 The varieties of imaginative experience

What would life be like without imagination? Perhaps, in this very first question, we have found something that is impossible to imagine. Imagination infuses so much of what we do, and so deeply, that to imagine its absence is to imagine not being human. Some people, I am told, think about sex every five minutes. For them, I presume, a sudden loss of imaginative powers would be devastating. Some people (not necessarily the same ones), at certain points in their lives, think about getting married or having a child. They might imagine the sanctity of a white wedding or the horrors of having all their relatives in one place at one time, the patter of tiny feet or the exhaustion of sleepless nights. As they play, children imagine all sorts of things, and their ideas of what they want to be and do when they grow up are fundamental in their development. Most people have ambitions of one kind or another. Imagining being promoted, or seeing something you have done recognised publicly, plays an essential role in motivation. In our idle moments too, or in diverting ourselves amidst tedious tasks, we might imagine winning the lottery or our hero scoring the winning goal in a match or, more sinfully, an obnoxious colleague falling under a bus. When we meet or talk to anyone, whether we are assessing them as potential friends or enemies, lovers or colleagues, for either ourselves or others, we are imagining what they would be like in certain circumstances.

But the imagination is not just involved in thinking of ourselves or other people. When I look at a painting, or read a novel, or hear a piece of music, or taste a wine, I bring my imagination to bear in its appreciation. I imagine other things to compare it with, or simply allow my imagination free flight, making no effort to control the images that spring to mind. Or in creating something myself, I may conjure up an image or images of what I want to realise. Imagination is also involved in the most ordinary experiences. When I go for a walk, I might imagine what it is like to live in a particular house I see, or if it is dark, I might suddenly imagine that there is something following me. In thinking what to cook for dinner, I imagine what I can do with the ingredients I have. In choosing clothes, I imagine what they would go with and the occasions on which I might wear them. In perceiving anything, I might imagine it transformed in some way, coloured differently, radically restructured, or simply moved to another location. And even if I do not deliberately transform it in my mind, previous or anticipated experiences may influence how I perceive it.

Clearly, we talk of imagination across the full range of human experience. Indeed, it may be hard to find an experience in which the imagination is not somehow involved. But if this is so, then does ‘imagination’ really have a single sense or refer to a single faculty? Can any order at all be brought into the varieties of imaginative experience? What conceptions of imagination might be distinguished? And what philosophical issues arise, or are reflected, in our attempts to do so? We will explore these questions, in a preliminary way, in the first part of this course.

2.1 Meanings of ‘imagination’

A natural starting point is to consider the ways in which ‘imagination’ and related terms such as ‘imagine’ and ‘image’ are used in everyday contexts.

Activity 1

Imagine someone asking you to define ‘imagination’. What would you say?

Can you think of any cases where we would talk of ‘imagining’ but not of ‘images’?

Consider the connotations of the term ‘imaginary’. What do they suggest as to how the imagination is sometimes regarded?

What is it for someone to be ‘imaginative’? How do the connotations of ‘imaginative’ compare with those of ‘imaginary’, and what does this suggest as to our talk of imagination?

How would you explain the difference between ‘imagination’ and ‘fantasy’ (or ‘fancy’), as those terms are used today?

Discussion

You may have suggested one or more of various possible definitions. Perhaps you characterised ‘imagination’ as ‘the power to form images’. Alternatively, or additionally, you might have mentioned the capacity to conceive of what is non-existent or to conjure up something new. The definition of ‘imagination’ in the Concise Oxford Dictionary (6th edn) runs as follows: ‘Imagining; mental faculty forming images or concepts of external objects not present to the senses; fancy; creative faculty of the mind.’ This covers most of what might be thought of in an initial specification, although there is no indication here of the relationship between the various meanings.

One such case occurred in posing the first question: ‘Imagine someone asking you to define “imagination”.’ In answering this question, you do not need to conjure up any image in your mind. Perhaps an image of a particular person did go through your mind, but it is not essential. It is certainly not essential in the way in which an image might seem required if you were asked to imagine a hairy monster with six legs. In imagining that I have perfect pitch, or that everyone speaks Gaelic, or that there are parallel universes, what I am doing is conceiving of a possibility. There is a difference, then, between ‘imagining’ and ‘imaging’: imagining may involve imaging, but there is a broad sense of ‘imagining’ in which conjuring up images is not a necessary condition for imagining to occur. This is well brought out in the definition of ‘imagination’ that Simon Blackburn provides in The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy (1994, 187): ‘Most directly, the faculty of reviving or especially creating images in the mind's eye. But more generally, the ability to create and rehearse possible situations, to combine knowledge in unusual ways, or to invent thought experiments.’ As we shall see, however, even this more general characterisation does not do justice to the full range of meanings of ‘imagination’ in the philosophical literature.

‘Imaginary’ is contrasted with ‘real’. More specifically, what is ‘imaginary’ may be said to be ‘fanciful’ or ‘illusory’. It is with these senses in mind that we might talk of ‘merely imagining’ something, or of something existing ‘only in the imagination’. ‘Did you really see the knife in the bedroom, or did you only imagine it?’ ‘Her happiness was just a figment of his imagination.’ What these uses suggest is a connection between imagination and fancy or delusion, a connection that we can certainly find in the literature (both philosophical and non-philosophical). When we talk of someone having an ‘active imagination’, for example, we may well be using the phrase in a derogatory sense. But while important, these uses are only one strand in our complex talk of imagination. Imagining can occur without what is imagined being ‘imaginary’. I can imagine something that really happened or that genuinely could happen, and if images are indeed involved, then these may well have been acquired from previous actual experience.

If imagining always involved imaging, then someone who is ‘imaginative’ would be someone who is good at conjuring up images. If what is imagined is always ‘imaginary’, then someone who is ‘imaginative’ would be someone who is frequently deluded. But what we normally have in mind in calling someone ‘imaginative’ is the more general sense of ‘imagination’ that Blackburn specified. Someone who is imaginative is someone who can think up new possibilities, offer fresh perspectives on what is familiar, make fruitful connections between apparently disparate ideas, elaborate original ways of seeing or doing things, project themselves into unusual situations, and so on. In short, someone who is imaginative is someone who is creative. As far as the connotations of ‘imaginative’ are concerned, they suggest a more positive view of ‘imagination’ than do the connotations of ‘imaginary’. But taken together, it might be argued, the two sets of connotations indicate the two poles between which our talk of imagination takes place.

Nowadays, ‘fantasy’ has more connotations of unreality or delusion than ‘imagination’ does, although, as suggested in answer to the third question, ‘imagination’ can also be used with these connotations. In the Concise Oxford Dictionary (6th edn), ‘fantasy’ is defined as follows: ‘Image-inventing faculty, esp. when extravagant or visionary; mental image, daydream; fantastic invention or composition, fantasia; whimsical speculation.’ The noun ‘fancy’ is defined in a similar way. Compare this with the definition of ‘imagination’ cited above. ‘Fancy’ is given as one of the meanings of ‘imagination’, but there is no talk in the latter case of anything ‘extravagant’, ‘whimsical’ or ‘fantastic’. (The Concise Oxford Dictionary treats ‘fantasy’ and ‘phantasy’ as mere variants, but it is sometimes suggested in literary contexts that ‘phantasy’ indicates a more elevated or visionary power; see Brann 1991, 21.)

Etymologically, ‘imagination’ derives from the Latin word imaginatio, while ‘fantasy’ and ‘fancy’ derive from the ancient Greek term phantasia. In the works of Plato and Aristotle, phantasia meant the power of apprehending or experiencing phantasmata (‘phantasms’). Arguably, what phantasma originally meant was an ‘appearance’ – an occurrence of something appearing to be such-and-such, as when the sun looks to us as being only a foot across. But even in Aristotle's work, it was also used to mean ‘mental image’, which is how it was subsequently understood. Phantasia came to be translated by imaginatio and phantasma by imago in Latin, preserving the etymological and conceptual connection here, although the original Greek terms were also used in their transliterated form (i.e. employing the Latin rather than Greek alphabet, as I have done here) alongside their Latin correlates. In the seventeenth century, as Latin lost its place as the official language of philosophy, the terms that replaced phantasia and imaginatio in English were ‘fantasy’ – or ‘fancy’ or ‘phantasy’ – and ‘imagination’. In this initial period of English usage, there seems to have been no established distinction between the two terms. In his Leviathan of 1651, for example, Hobbes claimed that what ‘the Latins call imagination … the Greeks call … fancy’ (I, ii). By the end of the eighteenth century, however, the distinction between fantasy and imagination had more or less settled down into its current sense. In his Dissertations Moral and Critical of 1783, James Beattie wrote: ‘According to the common use of words, Imagination and Fancy are not perfectly synonymous. They are, indeed, names for the same faculty; but the former seems to be applied to the more solemn, and the latter to the more trivial, exertions of it. A witty author is a man of lively Fancy; but a sublime poet is said to possess a vast imagination’ (quoted in Engell 1981, 172).

This brief consideration of some of the uses of ‘imagination’ and related terms illustrates the range of the meanings involved here, and hints at some of the philosophical issues that will concern us in what follows. Does it make sense to talk of a single faculty of imagination? Can ‘imagining’ be defined? What role do images play in imagination? How does imagining differ from perceiving? What contribution does the imagination make to our thought processes? To what extent does the imagination involve distortion or illusion? What is the relationship between imagination and creativity?

2.2 Twelve conceptions of imagination

Can we say anything more systematic about the different ways in which we talk of imagination? In a paper entitled ‘Twelve conceptions of imagination’ (2003), Leslie Stevenson distinguishes the following meanings of imagination, which I list here (in italics) as he formulates them, together with my own examples to illustrate each one:

The ability to think of something that is not presently perceived, but is, was or will be spatio-temporally real. In this sense I might imagine how my daughter looks as I speak to her on the phone, how she used to look when she was a baby, or how she will look when I give her the present I have bought her.

The ability to think of whatever one acknowledges as possible in the spatio-temporal world. In this sense I might imagine how my room will look painted in a different colour.

The liability to think of something which the subject believes to be real, but which is not real. Stevenson talks of ‘liability’ rather than ‘ability’ here to indicate that there is some kind of failure in the cognitive process. In this sense I might imagine that there is someone out to get me, or Macbeth imagines that there is a dagger in front of him.

The ability to think of things one conceives of as fictional, as opposed to what one believes to be real, or conceives of as possibly real. In this sense I might imagine what the characters in a book are like, or imagine the actors in a film or play as the characters they portray, aware that the characters are only fictional.

The ability to entertain mental images. Here I might conjure up an image of a large, black spider or a five-sided geometrical figure.

The ability to think of (conceive of, or represent) anything at all. Here I might imagine anything from an object before me being transformed in some way to an evil demon systematically deceiving me.

The non-rational operations of the mind, that is, those kinds of mental functioning which are explicable in terms of causes rather than reasons. Here I might imagine that smoking is good for me since I associate it with the cool behaviour of those I see smoking in films. It may not be rational, but there is a causal explanation in terms of the association of ideas, upon which advertisers rely so much.

The ability to form beliefs, on the basis of perception, about public objects in three-dimensional space which can exist unperceived, with spatial parts and temporal duration. Here I might imagine that the whole of something exists when I can only see part of it, or that it continues to exist when I look away.

The sensuous component in the appreciation of works of art or objects of natural beauty without classifying them under concepts or thinking of them as practically useful. In looking at a painting or hearing a piece of music, for example, I may be stimulated into imagining all sorts of things without conceptualising it as a representation of anything definite, or seeing it as serving any particular purpose.

The ability to create works of art that encourage such sensuous appreciation. In composing a piece of music, the composer too may imagine all sorts of things without conceptualising it in any definite way in the sense, say, of having a message that they want to get across.

The ability to appreciate things that are expressive or revelatory of the meaning of human life. In contemplating a craggy mountain range at dusk, for example, or a painting by Caspar David Friedrich depicting such a scene, I may imagine how much we are subject to the awesome power of the natural world, and yet ourselves have the conceptual and imaginative power to transcend it all in thought.

The ability to create works of art that express something deep about the meaning of human life, as opposed to the products of mere fantasy. Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel, Shakespeare's Hamlet, Goethe's Faust, Beethoven's late string quartets or Wagner's Ring cycle might all be offered as examples of this final conception of imagination.

Any attempt at bringing order into discussions of the imagination runs the risk of arbitrariness and distortion, and many alternative divisions are possible. Indeed, Stevenson subdivides some of these conceptions and offers various illustrations, which might be taken to warrant adding to the main list. As a subdivision of the first conception, for example, he identifies ‘the ability to think about a particular mental state of another person, whose existence one infers from perceived evidence’ (2003, 241), which might be thought to deserve separate recognition. Nor are the conceptions he distinguishes either exhaustive or exclusive, as he admits himself, and there are many interrelationships that are, at best, only implicitly indicated. But the twelve conceptions he distinguishes provide a useful initial framework for locating the philosophical issues.

Activity 2

With any division – and particularly with a division into as many as twelve things – there is always the question, ‘Why this many?’ Why not, in this case, thirteen, or just two with further subdivisions? Looking down the list of the twelve conceptions, are there any ways of simplifying or bringing further order into the division, or any obvious omissions?

Discussion

It seems to me that the twelve conceptions fall naturally into three groups of four. The first four articulate ways in which the imagination is seen as differing from ordinary sense perception. The second four reflect more general conceptions of imagination, in which its relation to thought is stressed more than its relation to sense perception. The final four are concerned with the role of the imagination in aesthetic appreciation and creation. It is hard to think of any omissions, given the generality of the second group of conceptions, and in particular the sixth, ‘the ability to think of anything at all’. But you might feel that more specific conceptions deserve to be brought out from under the cover of the ones listed here. For example, the ability to see or make connections, to link what might initially seem disparate things or fields, is also an important conception in both the arts and the sciences – and not least in philosophy.

As far as the first four conceptions are concerned, the contrast with sense perception is fundamental to imagination. In sense perception we have some kind of conscious awareness of something that is actually before us in the spatio-temporal world. Where we are aware of something that is not actually before us in the spatio-temporal world, we speak of ‘imagining’ it. But this can take several forms. What we imagine can be real (but just not present at the time), merely possible, or even impossible; and where possible or impossible, we can believe it to be such or not. (There is argument over what kind of impossibility is allowed, however. Can you imagine a round square, for example? Or imagine that a banana is a gun? Or imagine being an insect?) This gives us Stevenson's first four conceptions. One or more of these conceptions is involved in every (more complex) conception of imagination that can be found.

Taken together, the first four conceptions already suggest a certain generality to imagination. Imagination may be said to be involved whenever we think of something not actually present to us. Even when we think of something present to us, i.e. perceive something, that (perceptual) thought may be informed – rationally or non-rationally – by thoughts of other things; so it is a natural move to see the imagination at work in all thought. This gives us the second group of conceptions, numbered 5 to 8 in Stevenson's list. If thinking of something involves having a mental image of it (a view which we will examine shortly), then we have the fifth conception. The sixth is the most general of these conceptions, and the seventh restricts the imagination to the non-rational operations of thought. The eighth makes specific the supposed role of the imagination in perception. Stevenson identifies a source of the fifth conception in Aristotle's work, as already noted above (section 2.1), and mentions Descartes too in this regard. All four conceptions he finds illustrated in Hume's philosophy, and the eighth in particular is also characteristic of Kant's philosophy.

The final four conceptions, numbered 9 to 12, concern the role of the imagination in aesthetic experience, and highlight the creative aspects of imagination. In the eighteenth century, when aesthetics as a discipline itself emerged, a distinction was drawn between the beautiful and the sublime. Flowers and birds were often given as examples of what is beautiful, while towering waterfalls in a thunderstorm and the starry firmament above provide good illustrations of what was seen as sublime. The beautiful gives rise to a kind of calm and comforting pleasure, while the sublime generates a more exhilarating pleasure, but one tinged with pain or fear. If we make use of this distinction, then we could say the following. Imagination is required in both the aesthetic appreciation and artistic creation of what is beautiful, which gives us the ninth and tenth conceptions, and also in both the aesthetic appreciation and artistic creation of what is sublime, which gives us the eleventh and twelfth conceptions.

2.3 A first attempt at defining ‘imagining’

So far I have made some preliminary remarks on the meanings of ‘imagination’ and related terms, and considered one attempt at distinguishing different conceptions of imagination. In a broad sense, ‘imagining’ means thinking in some way of what is not present to the senses. Imagining may involve, but is not the same as, imaging. In a derogatory sense, ‘imagining’ may mean ‘fantasising’, as suggested by their etymological roots in Latin and Greek, and our use of the term ‘imaginary’; in a more appreciative sense, it may mean ‘creating’, as suggested by our use of the term ‘imaginative’. In considering the twelve conceptions of imagination that Stevenson distinguishes, I divided them into three groups of four. The first group, numbered 1 to 4, highlight the point that, in imagining, I am aware of something that is not actually present to the senses. The third conception captures the sense of ‘imagining’ as ‘fantasising’. In the second group of conceptions, numbered 5 to 8, we have both the conception that imagining is imaging (the fifth conception) as well as further recognition that there may be an element of ‘fantasy’ or ‘delusion’ in imagination (the seventh conception). The creative aspects of imagination are explicitly reflected in the third group of conceptions, numbered 9 to 12.

What emerges from this is the possibility of defining ‘imagining’, in its most basic or core sense, as ‘thinking of something that is not present to the senses’. As I have noted, this sense certainly underlies Stevenson's first group of conceptions, which are divided according to whether what is thought is real (but just not present), possible or impossible, and if possible or impossible, whether it is believed to be such or not. We also saw how we might move from the first to the second group of conceptions. One way to think of what is not present to the senses is to conjure up an image of it, which gives the fifth conception. The sixth conception might seem even more general than the core sense. But if it is possible to think of anything regardless of whether it is present to the senses or not, then we might be tempted to identify the heart of any thinking with ‘imagining’. (We will return to this shortly.) As far as the example illustrating the seventh conception is concerned, it can certainly be claimed that what I ‘imagine’ – the goodness of smoking – is unreal, and hence cannot be present to the senses. So too, in my example illustrating the eighth conception, when I imagine that the whole of something exists when I can only see part of it, the part I do not see is not, of course, present to the senses. It is possible to argue, then, that the core sense of ‘imagining’ just suggested underlies Stevenson's second group of conceptions of imagination as well.

How might this core sense be seen as involved in the third group of conceptions, concerning aesthetic appreciation and creation? In all four conceptions, we have the idea of imagining all sorts of things without fixing on any single definitive conceptualisation or representation. So here too we have thinking of things that are not directly present to the senses, things which go beyond what is strictly or literally perceived or created, although the thought of those things may well be triggered by what lies before the senses.

What Stevenson's conceptions suggest, then, is this. If it is possible to identify a core sense of ‘imagining’, then an obvious candidate is ‘thinking of something that is not present to the senses’. Admittedly, this is rather vague and general. But any sense that might be offered as underlying all twelve of Stevenson's conceptions is bound to be vague and general. And there may be virtue in its vagueness. For bearing it in mind may make us less likely to restrict our attention to just a few kinds of case, and more willing to consider the complex relationships that ‘imagining’ has both to other mental acts and to the wider context in which it occurs. Vague and general though it may be, it is also a sense that has often been articulated and, as we will see, has had a role to play in talking of imagination.

Activity 3

Consider the following case. You look out of the window and see a small tree with two branches sticking out from its sides that look like arms and a clump of leaves on top that looks like a head. You know very well that it is a tree, but you ‘imagine’ it as a person. Is this a counter-example to the claim that imagining is thinking of something that is not present to the senses?

Discussion

In one way, it might seem obviously not. For are you not imagining something – namely, a person – that is not present to the senses? On the other hand, there is certainly something present to the senses that provides a kind of sensory basis for what you imagine. Merely talking of ‘thinking of something that is not present to the senses’ arguably does not do justice to what is going on here. What you are imagining is that something that is present to your senses is something else. So one might feel that some kind of qualification is needed.

What we have here is a case of what is called ‘seeing-as’. We see the tree as a person, and in this case at least it also seems reasonable to describe what is going on as ‘imagining’ the tree as a person. Wittgenstein remarks on the topic of seeing-as. Wittgenstein does not talk of ‘imagining’ in all cases of seeing-as, which we might take to indicate – if we agree with him – that what we have here is a special kind of case. We could still claim, in other words, that the definition of ‘imagining’ as ‘thinking of something that is not present to the senses’ captures its core sense, while allowing qualifications or even departures from it in certain cases, which might then be counted as ‘non-standard’. But we should keep in mind that such qualifications or departures may be necessary.

Any adequate definition of a term should lay down both necessary and sufficient conditions for its applicability (in all the main kinds of case). If we can handle such cases as imagining a tree as a person, then we might take ‘thinking of something that is not present to the senses’ as a necessary condition of imagining. If I imagine something, then I am thinking of something that is not present to my senses. Without such thinking, there could be no imagining. But is it a sufficient condition? If I am thinking of something that is not present to the senses, then am I imagining it? The core sense suggested by Stevenson's twelve conceptions is admittedly vague and general. But is it too general?

Activity 4

Can you think of (imagine?) any examples of ‘thinking of something that is not present to the senses’ that you would not describe as imagining?

Discussion

There are various possible counter-examples that might be suggested. Here is one important kind of case. What is involved when you remember something? Are you not thinking of something that is not present to the senses (at that time)? Yet remembering something is not the same as imagining it. What we have, then, is a case of ‘thinking of something that is not present to the senses’ that would not be described as imagining. Thinking of something that is not present to the senses is not a sufficient condition for imagining.

What is the difference between remembering and imagining something? When we talk of remembering something, we imply that what is remembered actually happened or is true. (We need the clause ‘or is true’ to cover cases such as remembering a mathematical equation or remembering that I have an appointment tomorrow.) There is no such implication in talk of imagining something. But did I not admit, in illustrating Stevenson's first conception, that I can imagine something that actually happened or is true? We can indeed imagine what actually happened or is true, but when we talk of imagining it, there is nevertheless a recognition that we could be wrong (even if we are not). That what we are imagining actually happened or is true is a merely accidental or contingent feature of our imagining, in the following sense. If it had not happened or were not true, then we would still talk of imagining it; whereas if something that we claim to remember had not actually happened or were not true, then we would regard talk of ‘remembering’ here as illegitimate.

What this suggests, then, is that the definition of ‘imagining’ as ‘thinking of something that is not present to the senses’ is inadequate as it stands. While it arguably lays down a necessary condition for imagining, it does not lay down a sufficient condition. The definition is too general, since it includes things – such as remembering – that we would not count as imagining. If what we have said in distinguishing imagining from remembering is right, then in imagining something we are not just thinking of something that is not present to the senses, but also thinking of something that need not have actually happened or that need not be true. But can more be said about this additional requirement? Or are there alternative or better specifications? One attempt to offer a more restricted definition has been made by Berys Gaut in a paper entitled ‘Creativity and imagination’ (2003), an extract from which is included as a reading in section 2.4.

2.4 Gaut's analysis of imagination

Berys Gaut's main concern in his paper is to provide an account of the relationship between imagination and creativity. But in section 2 of his paper he offers an analysis of the notion of imagination, which we will look at here.

Activity 5

Read the introduction to Gaut's paper and then section 2, entitled ‘Imagination’. You should read the whole section at least once through first, and then consider each paragraph more carefully as you answer the following questions, which are partly intended to guide you through a more detailed reading. The penultimate paragraph, in particular, packs in a number of different issues. You should concentrate, at least initially, on picking out the main point or points.

Click on the 'View document' link below to read Berys Gaut on 'Creativity and imagination'.

In the first three paragraphs of section 2, Gaut distinguishes four uses of the term ‘imagination’. What are these four uses, and how do they relate to what I have already said, and to Stevenson's conceptions?

In the fourth and fifth paragraphs, Gaut argues against identifying imagining with imaging. What is his argument? Do you find it convincing?

In the sixth paragraph, Gaut presents his basic conception of what he calls (at the beginning of the seventh paragraph) ‘propositional imagining’. How does he articulate this conception? Gaut offers several formulations, which he claims are equivalent. Are they equivalent? (There are a number of technical terms used here. You should focus on Gaut's basic conception.)

In the seventh paragraph, Gaut explains what he calls ‘objectual imagining’. What is this further kind of imagining, and how does Gaut see his account of propositional imagining being extended smoothly to cover it? Is he right that ‘imagining some object x is a matter of entertaining the concept of x’?

The eighth paragraph is the most difficult of all. Gaut distinguishes a third kind of imagining, which he calls ‘experiential imagining’, covering both ‘sensory imagining’ and ‘phenomenal imagining’. What are these? Experiential imagining, he says, involves imagery. But since not all imagery implies imagining, what does Gaut suggest is the difference between imagery that is, and imagery that is not, a form of imagining? How does he see the relation between experiential and propositional imagining?

In the final paragraph, Gaut considers a final kind of imagining, ‘dramatic imagining’. What does he mean by this, and how is it related to the other kinds?

Discussion

In the first use that Gaut distinguishes, ‘imagining’ means ‘falsely believing’ or ‘misperceiving’. This (derogatory) use is related to the sense of ‘imagining’ as ‘fantasising’ mentioned above, reflecting the connotations of ‘imaginary’, and to Stevenson's third and seventh conceptions. In the second use that Gaut distinguishes, ‘imagining’ is more or less synonymous with ‘creating’. This is the more appreciative sense of ‘imagining’, reflected in the connotations of ‘imaginative’, and in the third group of Stevenson's conceptions (numbered 9 to 12). In Gaut's third use, ‘imagining’ means ‘imaging’, which is Stevenson's fifth conception. In the first three paragraphs, Gaut does not say exactly what the fourth use is. He merely says what it is not: ‘imagining’ is here to be distinguished from ‘imaging’. The first paragraph also suggests that he sees this as the core sense.

Gaut argues that there are cases of imaging – such as we find in memory, dreams and perception – that are not cases of imagining; and conversely, that there are cases of imagining – such as imagining an infinite row of numerals – that are not cases of imaging. We will return to the relationship between imagination and imagery later in this course. But with regard to this last example, you might have wanted to object that while no one can form an accurate mental image of an infinite row of numerals, they might well have some image in mind, such as a row of numerals going off into the distance. So even if having mental images cannot be all there is to imagining, the possibility has not yet been ruled out that imagery may be a necessary condition of imagination.

‘Propositional imagining’ is imagining that something is the case – imagining that p, or ‘entertaining the proposition that p’, as Gaut puts it. What is meant by ‘entertaining’ a proposition is thinking of it without commitment to its truth or falsity. Gaut offers two other formulations – thinking of the state of affairs that p, without commitment to the existence of that state of affairs, and thinking of p without ‘asserting’ that p. Gaut raises a doubt about the latter himself, and one might have doubts also about the appeal to ‘states of affairs’. Could there be a ‘state of affairs’ involving an infinite row of numerals, for example? It is not clear what this might mean. Yet Gaut would presumably admit that we can entertain propositions about infinite rows of numerals. So ‘entertaining propositions’ is arguably not the same as ‘thinking of states of affairs’. (Involved here, again, are questions about whether – or how – we can imagine ‘impossible’ things. There can be no state of affairs involving round squares, but can we imagine them? Have we not, at least, just entertained a proposition about them? More controversially, it might be argued that there can be no state of affairs in which a human is an insect, since humans and insects are essentially different. But did Kafka not write a story about this? Could we appeal to fictional states of affairs to get round the difficulty? Or does this just cover up the difficulty?) However, Gaut's main point is clear: as he conceives it, imagining that p is thinking of p without commitment to its truth or falsity (without ‘alethic’ commitment, as he puts it in more technical language).

‘Objectual imagining’ is imagining an object. Gaut suggests that, just as propositional imagining is a matter of entertaining a proposition, so objectual imagining is a matter of entertaining a concept. But what exactly is the relevant concept? Take Gaut's example of a wet cat. Can I not ‘entertain’ the concept of a wet cat without thinking of any particular cat (real or imagined)? Of course, Gaut defines ‘entertaining the concept of x’ as ‘thinking of x without commitment to the existence (or non-existence) of x’, so that by ‘concept of x’ he means ‘concept of a particular x’. Nevertheless, we should still distinguish between imagining a particular wet cat and thinking (without existential commitment) of wet cats in general. And perhaps we might want to go further, and draw a distinction too between imagining a particular wet cat and ‘merely’ entertaining the concept of that particular wet cat. Imagining, it might be objected, has more of a sensory quality than talk of entertaining concepts does justice to. (In effect, this objection is recognised in what Gaut goes on to say about ‘experiential imagining’.)

‘Experiential imagining’ is a richer kind of imagining, imagining with a ‘distinctive experiential aspect’, as Gaut describes it tautologically. More specifically, he suggests, it covers both sensory imagining and phenomenal imagining. As an example of the former, he gives visually imagining something, and as an example of the latter, imagining what it is like to feel something. In both cases, he says, imagery is involved. But as he argued in the fourth paragraph, imagery does not in itself imply imagining, since imagery can occur in remembering, dreaming and perceiving. So what distinguishes imagery that is, and imagery that is not, a form of imagining? According to Gaut, to have an image is to think of something, and the content of that thought can either be ‘asserted’ or ‘unasserted’. Having an image is a kind of imagining, he says, when the thought-content is unasserted. (Talking of a thought-content having ‘intentional inexistence’ is just a technical way of saying that what we think of on a given occasion exists in thought, even if not in reality.) So experiential imagining is like propositional imagining in having an unasserted thought-content. The difference between experiential and propositional imagining, according to Gaut, lies in the way in which the thought-content is presented. In propositional imagining, that content is merely ‘entertained’; in experiential imagining, it is visualised or otherwise represented with imagery. In visually imagining a wet cat, for example, I conjure up an image of a wet cat: this is experiential (sensory) imagining. Experiential imagining may well involve propositional and objectual imagining, but imagery is what gives it its experiential character.

‘Dramatic imagining’ is imagining what it is like to be someone else or to be in someone else's position. Gaut sees it as even richer than experiential imagining, but as ultimately reducible to the first three kinds of imagining.

Central to Gaut's account is the idea that mental acts have a ‘thought-content’ that can be thought of in different ways. The idea is often expressed by saying that mental acts involve the adoption of a certain attitude to a proposition – a ‘propositional attitude’ – or, in the case of objects, involve thinking of an object under a certain ‘mode of presentation’. Take the thought or proposition that Immanuel (my cat) is wet. I can adopt various propositional attitudes to this. I can believe it, I can desire it, I can fear it, or I can imagine it, to mention just four. On Gaut's conception, to imagine it is to think of it without commitment to its truth or falsity. To believe it, on the other hand, as Gaut himself notes, is to think of it with commitment to its truth. But in both cases, the ‘thought-content’ of the propositional attitude is the same – the proposition that Immanuel is wet. The basic idea suggests, too, that there is a kind of bare thinking of this proposition lying at the core of the mental acts, which one might even be tempted to identify as ‘imagining’ in the most general sense possible. (This would give us Stevenson's sixth conception.) Certainly, imagining comes out as a form of thinking, for it involves thinking of a proposition or object (but without alethic or existential commitment, i.e. without commitment to its truth or falsity, or its existence or non-existence, respectively).

The appeal to ‘propositions’, however, is more controversial than Gaut's account implies. What are ‘propositions’? I have already raised doubts as to whether they can be construed as ‘states of affairs’. Even understanding them simply as ‘thought-contents’ is problematic. For it has proved notoriously difficult to provide criteria of identity for such contents. Can one really identify one and the same ‘thought-content’ across the various mental acts? If there is at least some sense in which imagination plays a role in perception itself, then specifying a ‘thought-content’ independent of the act of imagining may be more difficult than one might assume. However, let us leave this can of worms for the moment. Let us just accept the tautological point that, when I imagine or think of something, there is something that I am imagining or thinking of. And let us take Gaut's example of a wet cat. There is a whole range of imaginings that might, in some sense, have a particular wet cat, say Immanuel – or the ‘state of affairs’ in which Immanuel is wet – as their ‘thought-content’. I can imagine that Immanuel is wet, I can imagine a wet Immanuel, I can conjure up an image of a wet Immanuel, I can visually imagine Immanuel as wet, I can imagine Immanuel (who is standing dry before me) as wet, I can imagine what it is like to be as wet as Immanuel, I can imagine (perhaps) what it is like to be wet Immanuel, I can imagine (perhaps) what it is like to be in wet Immanuel's paws, and so on. Obviously, I have set it up this way, but there is clearly something that relates these various imaginings, and the natural thing to say is that they all concern a wet Immanuel, and furthermore involve thinking of a wet Immanuel in some way, a way that does not commit me to taking Immanuel as actually wet. It seems plausible to regard imagining, then, in a wide variety of cases, as thinking of something without alethic or existential commitment. At any rate, this is what Gaut offers as the core sense of ‘imagining’, and which we can take as constituting his main definition.

Activity 6

How does Gaut's definition compare with the general definition suggested by Stevenson's twelve conceptions? Are they equivalent? Does one follow from the other?

Do any of the examples I gave to illustrate Stevenson's twelve conceptions provide counter-examples to Gaut's definition? If so, how might Gaut respond?

I considered possible counter-examples to the general definition in the last section (Section 2.3). Are they also counter-examples to Gaut's definition?

Is Gaut's definition an improvement on the general definition?

Discussion

In both cases, imagining is defined as a form of thinking. But while on the general definition imagining is thinking of something that is not present to the senses, on Gaut's definition imagining is thinking of something without commitment to its truth or falsity, existence or non-existence. The two are not equivalent, since Gaut's definition does not follow from the general definition. To take the case of objects, if I am thinking of something that is not present to the senses, then it does not follow that I am not committed to its existence or non-existence. (Nor does it follow that I am committed.) However, the general definition does follow from Gaut's definition. For if I am thinking of an object without commitment to its existence or non-existence, then it follows that it cannot be present to the senses, since otherwise, presumably, I would be committed to its existence. Being acknowledged to exist is part of what is meant by being ‘present to the senses’, as that phrase is intended to be understood here.

Stevenson's very first conception provides a counter-example to Gaut's definition. For in imagining how my daughter looks as I speak to her on the phone, I am certainly committed to her existence. Gaut might reply that I am not committed to the particular way I imagine she looks. Might I not be wrong? But perhaps I do know how she looks, and can imagine it precisely. Stevenson's third conception provides a further counter-example. For when Macbeth imagines that there is a dagger in front of him and reaches out towards it, he is committed (at least at that point) to its existence (even if he is wrong). Gaut might reply here that he has admitted that imagining can sometimes mean ‘believing falsely’ or ‘misperceiving’ (this was the first use he distinguished, in the first paragraph of section 2 of the reading), but that this is not its core sense. But why should we not try to reflect it in our main definition, if we can? Stevenson's fourth, seventh and eighth conceptions provide further counter-examples. In ‘imagining’ fictional characters, I may be well aware that they are not real. In ‘imagining’ that smoking is good for me, I may actually believe it. And in ‘imagining’ that the whole of something exists when I can only see a part of it, I am certainly committed to its existence. Perhaps Gaut would see these too as derivative or non-standard senses, but the counter-examples seem to be extensive.

The example from Activity 3 only adds to the counter-examples to Gaut's definition that I have already mentioned. For in imagining a tree as a person, I may be perfectly aware that no such person exists, i.e. I may well be committed to the non-existence of what I imagine. However, Gaut's definition does suggest an answer to the problem raised in the discussion of Activity 3. On Gaut's conception, in imagining something I am not committed to the truth or existence of what I imagine, whereas in remembering something, he would presumably argue, I am so committed. So the requisite distinction between imagining and remembering can be drawn.

The definition suggested by Stevenson's twelve conceptions was too general in including things that do not count as imagining, such as remembering. In indicating the relevance of issues of truth and existence, Gaut's definition is an improvement. However, the requirement that, in imagining something, I am not alethically or existentially committed seems too strong. It rules out too many cases in which it seems perfectly legitimate to talk of ‘imagining’. In all these cases, I can imagine something while being firmly committed to either its existence or non-existence, truth or falsity. There are too many counter-examples, in other words, for Gaut's definition to be acceptable as it stands, at least if we are trying to capture a basic sense that underlies all the main uses of ‘imagine’.

Can a definition be offered that is better than both the general definition and Gaut's definition? What seems to be needed is a definition that is more specific than the general definition, yet less specific than Gaut's definition. Gaut is right that issues of truth and existence are relevant, but they are relevant, I think, in a different way to the one he supposes. At the end of the last section, it was suggested that, in imagining something, I am thinking of something that need not be true or existent (in either the past, present or future) in the sense that, were it not true or existent, it would still be legitimate to talk of my ‘imagining’ it. I may well be alethically or existentially committed myself, but my thinking would still count as imagining even if I were wrong in my alethic or existential commitment. The actual truth or existence of what I am imagining, in other words, is not essential to the imagining itself in the way that it is essential to perceiving or remembering by contrast.

If a definition of ‘imagining’ can be offered at all, then it is something along these lines that I think is needed. But the suggestion will not do as it stands. For we now seem to have lost the distinction between imagining and believing. In believing something, am I not also thinking of something that need not be true or existent, in the sense indicated? So what is the difference between imagining and believing? Gaut characterised this as the difference between thinking of something without alethic or existential commitment and thinking of something with such commitment. But if what I have said is right, then imagining too can occur with alethic or existential commitment. An obvious response is to say that while in the case of believing, I cannot believe something without commitment to its truth or existence, in the case of imagining, I can imagine something without such commitment, or indeed with commitment to its falsity or non-existence. This is true, of course. But it does not enable us to distinguish cases of believing something with commitment to its truth or existence from cases of imagining something with commitment to its truth or existence. How can we draw this distinction? Perhaps all we need is a minor refinement to my current suggestion, on the basis of which we can then draw the following contrast. In the case of imagining, if what I imagine were not true or existent, and I were to realise this, then it would still be legitimate for me to talk of ‘imagining’. But in the case of believing, if what I believe were not true or existent, and I were to realise this, then I could no longer talk of ‘believing’ it.

This is correct as far as it goes, but it obscures what I think is the crucial point here. Consider the case of Macbeth's imagining that there is a dagger before him, as he feverishly prepares to kill Duncan at the start of Act II of Shakespeare's play. Does he not also, as he reaches out to take it, believe that there is a dagger before him? And is this believing not part of his imagining? In the core sense of ‘imagine’ as Gaut defines it, the answer to this latter question would have to be ‘No’. But as we have seen, Gaut does allow that ‘imagine’ can sometimes mean ‘believe falsely’. So his considered answer would presumably be: ‘Yes, but not in the core sense of “imagine”’. However, a different response is possible that does not force us to distinguish two incompatible senses of ‘imagine’. The crucial point, I think, is this. To say that Macbeth ‘believes’ there is a dagger before him implies that he is committed to the existence of a dagger before him. But to say that he ‘imagines’ that there is a dagger before him implies not that he is not committed to the existence of a dagger before him (though he may be), but that we are not committed to its existence in describing him as ‘imagining’ it. The lack of commitment to the truth or existence of something, in other words, lies not so much on the side of the person who is being described as ‘imagining’ something, as on the side of the person who is doing the describing. In talking of ‘imagining’, it is we who are indicating that lack of commitment. Of course, someone can themselves talk of ‘imagining’ something, as Macbeth in effect goes on to do (after he fails to take hold of the dagger he initially believes to be before him), but this would indicate their own lack of commitment to the truth or existence of what they are thinking of. On this alternative account, then, Gaut is right about the relevance of considerations of truth and existence, but he has brought them in at the wrong place.

2.5 The problematic status of the imagination

Let us review the position we have reached. Stevenson's twelve conceptions of imagination suggest that ‘imagining’ might be defined as ‘thinking of something that is not present to the senses’. This definition succeeds in distinguishing imagining from perceiving, but is too general in including such things as remembering. Gaut defines ‘imagining’, in its core sense, as ‘thinking of something without commitment to its truth or falsity, existence or non-existence’. This succeeds in distinguishing imagining from both perceiving and remembering, but is arguably too specific in excluding too many standard cases of imagining (i.e. cases that ought really to be captured in any core sense we specify). Can a better definition be offered? My alternative account might suggest the following possibility. ‘Imagining’ means thinking of something that is not present to the senses and that may or may not be true or existent, thinking which, in being called ‘imagining’, indicates a lack of commitment to the truth or existence of what is thought of by the person calling it such.

But in what sense is this a definition, and what are the implications of the suggested alternative account? If talk of ‘imagining’ says something about the person using the term (namely, that they are not committed to the truth or existence of what is being thought of) and not just about the person doing the thinking, then ‘imagining’ cannot be taken to denote a specific kind of mental activity or state. The definition, then, does not provide necessary and sufficient conditions for something to be imagining, but rather, to the extent that it is correct, explains our use of the term ‘imagining’. In describing someone as ‘imagining’ something, we are indeed describing them as thinking of something, something that is not present to the senses. But at the same time we are evaluating that thinking, in refraining from committing ourselves to the truth or existence of what is being thought of. On some occasions, we may be implying something stronger, that we are committed to the falsity or non-existence of what is being thought of, as when we say that someone is ‘merely imagining’ something. On other occasions, there may be other implications too. But we might see the definition as capturing what is minimally involved in all the basic uses of the term ‘imagining’. However, the key point is that, in using a term such as ‘imagining’, we are not just referring to some mental activity, but also evaluating that activity in some way. The general idea here – that we must reject the assumption that terms such as ‘imagining’ get their meaning by simply denoting mental states or processes – is particularly associated with the work of Wittgenstein. Indeed, it is not too much of an exaggeration to say that this is the governing idea of Wittgenstein's philosophy of mind. Although Wittgenstein does not say as much about ‘imagining’ and its cognates as he does about other mental terms, and does not himself offer the suggested alternative account, which reflects merely the spirit of his thought, the case of ‘imagining’ provides a good way to illustrate Wittgenstein's philosophy.

Without saddling Wittgenstein with the suggested alternative account, then, what are the implications of what might nevertheless be called a Wittgensteinian view of imagining? If ‘imagining’ does not denote a specific kind of mental activity, categorically distinct from forms of thinking such as believing, then talk of ‘imagination’ – as the faculty responsible for ‘imagining’ – may be misleading. This might seem disconcerting, but it does offer the beginnings of an explanation of the problematic status that the imagination has had throughout the history of western philosophy. From ancient Greek thought onwards, the imagination has been invoked in describing and explaining certain kinds of unusual or puzzling experiences or phenomena, but it has proved enormously difficult to say just what the imagination is. But if ‘imagining’ does not denote a specific kind of mental activity, then it is not surprising that it has been hard to say exactly what it is; and if our use of ‘imagining’ partly expresses an evaluation on our part of a mental activity, then it is not surprising that it should be invoked in trying to account for these experiences or phenomena where we may well be unsure about matters of truth or existence.

In fact, the imagination has been invoked not just in describing and explaining unusual or obviously puzzling experiences or phenomena. In the work of Hume and Kant, for example, the imagination is seen as involved in all forms of perceptual judgement; and in Romanticism, which was heavily influenced by Hume and Kant, we find the imagination glorified as the most important cognitive power. In his essay ‘On the imagination’ (1817), Coleridge declared: ‘The primary IMAGINATION I hold to be the living Power and prime Agent of all human Perception, and as a representation in the finite mind of the eternal act of creation in the infinite I AM’ (1983, 304). Wordsworth described the imagination, in Book XIII of The Prelude, as ‘but another name for absolute strength/And clearest insight, amplitude of mind/And reason in her most exalted mood’ (quoted in Wu 1998, 405). But despite the virtually unlimited powers accorded to the imagination, or perhaps because of it, one is hard pressed to find clarification of the nature of the imagination in Romantic writings, and one must look to Hume and Kant for the source of this conception.

Partly in reaction to the excesses of Romanticism, discussion of imagination has been relatively absent in recent philosophy of mind. Sensation and perception, thought and language, content and representation, consciousness and intentionality are all topics that are standardly covered in textbooks, but not imagination. However, there are a few notable exceptions. Eva Brann, for example, in The World of the Imagination (1991), makes the most substantial effort to date to explore the imagination in all its relations and ramifications. The imagination, she remarks in her preface, ‘appears to pose a problem too deep for proper acknowledgment. It is, so to speak, the missing mystery of philosophy’ (1991, 3). In referring to this ‘missing mystery’ later on, with Kant specifically in mind, she writes:

the imagination emerges as an unacknowledged question mark, always the crux yet rarely the theme of inquiry. It is the osmotic membrane between matter and mind, the antechamber between outside and inside, the free zone between the laws of nature and the requirements of reason. It is, in sum, the pivotal power in which are centered those mediating, elevating, transforming functions that are so indispensable to the cognitive process that philosophers are reluctant to press them very closely.

(1991,32)

In The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and Reason (1987), Mark Johnson has also argued against the marginalisation of the imagination in contemporary philosophy and cognitive science. His book opens with similarly grandiose claims:

Without imagination, nothing in the world could be meaningful. Without imagination, we could never make sense of our experience. Without imagination, we could never reason toward knowledge of reality … It is a shocking fact that none of the theories of meaning and rationality dominant today offer any serious treatment of imagination.

(1987, ix)

In the sixth chapter of his book, Johnson outlines the theory of imagination that he thinks is required, developing Kant's account. It is significant that both Brann and Johnson appeal to Kant in arguing for the importance of the imagination. For the imagination is indeed accorded a central role in Kant's philosophy, and it is natural to see Kant's conception of imagination as the model here.

Despite its importance, however, even Kant described the imagination as a ‘hidden art in the depths of the human soul, whose true operations we can divine from nature and lay unveiled before our eyes only with difficulty’ (1997, A141–2/B180–1). [Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason was first published in 1781, and a second, revised edition appeared in 1787. In a number of places there are significant differences, and most modern editions, while based on the second edition, note the original formulations and, where an entire section has been changed, give the whole of the first version as well. Standard references to the Critique are given in the form ‘Ax/By’, where ‘A’ and ‘B’ indicate the first and second editions, respectively, and ‘x’ and ‘y’ give the relevant page numbers of the original editions, which are also given in the margins of modern editions.] So Brann might seem right in calling the imagination a ‘missing mystery’. But is there really a ‘missing mystery’ here, in the sense she has in mind? There may be a great deal of philosophical work to do in clarifying our talk of imagination, in understanding the complex ways in which the imagination is invoked, and in explaining the intricate relations between our concepts of perception, imagination, thought, and so on. But if the Wittgensteinian view suggested above is right and ‘imagining’ does not denote a specific kind of mental activity, then there is nothing that has the astonishing powers attributed to ‘imagination’, and so, as far as this goes, nothing to explain. There is no problem here that is ‘too deep for proper acknowledgment’. Nor is it ‘shocking’ that current theories of meaning and rationality do not offer any ‘serious treatment’ of imagination, at least in the sense that Johnson has in mind. It may be regrettable, but it is not clear that the imagination must be accorded pride of place in any such theory. In any case, to use a distinction that Wittgenstein draws, what may be needed is not so much a theory of imagination that ‘solves’ the mystery of imagination as a conceptual clarification that ‘dissolves’ it – that demystifies the imagination.

3 Imagery and supposition

Whatever view one takes of whether or how ‘imagining’ can be defined and whether there is a deep mystery here or not, it remains the case that there are many different conceptions of imagination, which are combined in different ways, sometimes in harmony, sometimes in tension, in the work of individual thinkers (the work of Descartes, Hume, Kant and Wittgenstein together give a good sense of the range of different conceptions, the ways in which the imagination is invoked, and the philosophical issues that arise). However, if there is a single issue that lies at the heart of debates about the imagination, then it is the tension between what might be described broadly as sensory and intellectual conceptions of the imagination. In the rest of this course, we will look at two questions that highlight this tension: whether imagery is a form of imagination, and whether supposition is a form of imagination. On the one hand, as reflected in Stevenson's first four conceptions, imagination is conceived in relation to sense perception, the only difference being the presence of the relevant object. In perception, we are aware of something that is present to the senses; in imagination, we are aware of something that is not present to the senses. What relates imagination to perception, it is often thought, is the presence in both of some kind of ‘image’ of what we are aware of. So imagery is regarded as essential to imagination (see Stevenson's fifth conception). But is this right? We will examine this issue in the next section. On the other hand, imagining is conceived as a kind of thinking. Since, more specifically, it is conceived as thinking of something whose truth or existence is somehow in question (whether on our part or on the part of the person doing the thinking), it has seemed natural to call this type of thinking ‘supposing’. So supposition has been seen as a form of imagination. We will look at this issue in the final section of this course.

3.1 Imagination and imagery

From the very origins of concern with the imagination in the work of the ancient Greeks, the imagination has been associated with imagery. But what is the relationship between imagination and imagery? In chapter 12 of his book, The Language of Imagination (1990), Alan White addresses this question and argues that imagination neither implies nor is implied by imagery.

Activity 7

Read the extract from White's book.

Click on the 'View document' link below to read Alan R. White on 'Imagination and imagery'.

What is White's claim in the first paragraph of the extract? How does he argue for this claim, and how convincing is his argument?

What further argument for this claim does he provide in the second paragraph? How convincing is this further argument?

What is White's claim in the third paragraph? How does he argue for it, and how convincing is his argument?

In the fourth paragraph, White goes on to consider a ‘more debatable problem’. What is this problem, and what is White's ‘short answer’?

In the last three paragraphs, White suggests a number of differences between imagination and imagery. We will look at these in more detail in a moment. But to what specifically is imagining being contrasted?

Discussion

White's claim is that imagination does not imply imagery, for which he argues by offering counter-examples. One might have doubts about some of them. In imagining what the neighbours will think, for example, might I not have an image of the neighbours? Having such an image may not constitute the imagining, but might someone not object that some such image is necessary? But in cases such as imagining an objection (as I have just done), although images may be involved, here too it seems implausible to argue that they must be. So it seems right to conclude that imagination does not imply imagery, even if it may involve it in particular cases.

White's further argument might be formulated as an (attempted) reductio ad absurdum of the claim that imagination implies imagery:

Imagination implies imagery.

Imagery implies images.

Images must resemble ‘in some copyable way’ what they are images of.

Therefore, we can only imagine what can be ‘copied’ as an image.

But we can imagine far more than what can be ‘copied’ as an image.

So imagination does not imply imagery.

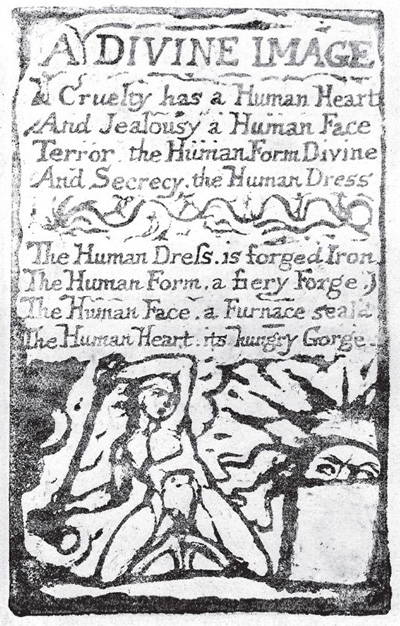

(1) is the premise that White wants to reject. (2), (3) and (5) are the additional premises, which White accepts, at least here. (In fact, later on in the chapter, White goes on to reject (2) as well, but he does not comment on the implications of this for his earlier argument.) From (1), (2) and (3) he infers (4), but since this is in conflict with (5), he concludes that (1) is false. But as the argument has been formulated, there are clearly other possibilities. Why, in particular, should we accept (3)? Why should images be restricted merely to images of what is ‘copyable’? Can we not have images of abstract things? Consider the plates that William Blake prepared for his poems in Songs of Innocence and of Experience (an example is given in Figure 1). Do these not offer images of things that are not ‘copyable’ as White seems to understand this? Or consider solving a geometrical problem. Can I not draw exactly how I imagined the problem could be solved? White's further argument seems unconvincing, then, and adds little to his first argument, although it does reveal an assumption he makes about what ‘images’ are.

Imagination, White has argued, does not imply imagery. In the third paragraph, he argues for the converse: namely, that imagery does not imply imagination. He again proceeds by offering counter-examples. We can have images in dreams and memory, for example, or after-images and hallucinations, but would not speak of ‘imagining’ here, he suggests. However, it may be open to us to regard imagination as playing some role in such experiences, although we might agree that the mere having of images does not constitute imagining.

As White formulates it, the ‘more debatable problem’ is whether, when imagery does occur in imagining, it plays an essential role, i.e. whether there are some forms of imagination in which imagery is essential. White wants to argue that there are no such forms, since there are intrinsic differences between imagination and imagery.

The contrast that White is drawing seems to be between imagining and the mere having of images. It is worth keeping this in mind in assessing the differences he alleges between imagination and imagery.

The poem in Figure 1 was originally written for Blake's Songs of Experience (1794), as the counterpart to ‘The divine image’ of his earlier Songs of Innocence (1789), but it seems not to have been used in any of the copies of the combined Songs that Blake produced in his lifetime. The plate that Blake prepared for it was never coloured, and the poem is only known from a print made after Blake's death (see Keynes 1970,13,125; Wu 1998,84). ‘The divine image’ of the Songs of Innocence has five verses, of which the third runs as follows: ‘For Mercy has a human heart/Pity, a human face:/And Love, the human form divine,/And Peace, the human dress.’ The contrast between this and the poem above is stark, a reaction perhaps to the horrors of the French Revolution. But Blake presumably then felt that it was too extreme, though the plate itself was obviously not destroyed. The poem that actually appeared as the counterpart to ‘The divine image’ was ‘The human abstract’, which is far subtler in tone.

As Keynes describes it in his facsimile edition, Blake's plate shows ‘Los, the poet and craftsman, forging the Sun, symbol of imagination, into the words of his poem with furious blows of his creative sledge-hammer on the anvil’ (1970, 125). The plate may be literally an image of someone hammering something on an anvil, but it clearly represents far more – the way in which our sensitive, imaginative nature can be beaten out of us by hatred and brutality, as revealed in the violence of the French Revolution or the oppression of industrialisation, for example. The plate is an image, in other words, of far more than what is merely ‘copyable’.

In the final three paragraphs of the extract, White seems to be making quite a strong claim: that imagery never plays an essential role in imagination. But is this right? To answer this, let us consider a response to White's arguments that is made by Gregory Currie and Ian Ravenscroft in Recreative Minds (2002). In their first chapter, Currie and Ravenscroft distinguish between recreative and creative imagination. By ‘recreative imagination’ they mean the capacity to recreate in our minds states that are in some sense ‘counterparts’ to perceptions, beliefs, desires, and so on (2002, 11). In imagining a cat, for example, my imagining is some kind of ‘counterpart’ to seeing it. The ‘creative imagination’, on the other hand, is involved in creating something valuable in art, science or practical life, but this is only mentioned in order to be put aside (2002, 9). Their concern is with recreative imagination, and mental imagery, they suggest, is one important kind. In their second chapter, they offer arguments for this view, or more specifically, respond to White's arguments against this view.

Activity 8

Read the extract from Currie and Ravenscroft (‘Is imagery a kind of imagination?’). What are the four arguments that Currie and Ravenscroft find in White's discussion, and what is their response to each one? Do they do justice to White's arguments, and provide a convincing refutation?

Click on the 'View document' link below to read Gregory Currie and Ian Ravenscroft on 'Is imagery a kind of imagination?'.

Discussion

Let us consider each of the four arguments in turn.

According to White's first argument (drawn from the third and fifth paragraphs of the reading ‘Imagination and imagery’), imagination is under voluntary control while imagery is not, or at best under only minimal control. But as Currie and Ravenscroft point out, there are cases of imagination too that are not under voluntary control. So there seems to be no basis here for claiming any essential difference between imagination and imagery.

According to the second argument (drawn from the fifth paragraph of the White extract), imagining, unlike having an image, is something that I do. White does not put it like this himself, but the message is arguably the same. White talks of having imagery, unlike imagining, being an experience. Imagery happens to one; in imagining something, one is active. But as Currie and Ravenscroft remark, imaginings ‘can come and go independently of one’ in just the way that imagery can. So again, it would seem, there is no basis here for claiming an essential difference.

According to the third argument (also drawn from the fifth paragraph of the White extract), imagery, unlike imagination, ‘has an objectivity and independence’. But again, as Currie and Ravenscroft point out, I can be just as surprised by features of what I imagine as I can by features of my images. So they again seem right to reject White's argument. According to the fourth argument (drawn from the sixth paragraph of the White extract), imagery ‘is particular and determinate, whereas imagination can be general and indeterminate’, as White puts it himself. This is controversial, as White recognises in a footnote to the paragraph. Currie and Ravenscroft claim that images can be indeterminate too, just as imagining can be particular, which seems right. So this fourth argument too seems not to establish any essential difference between imagery and imagination.

In the seventh paragraph of a second extract from White (see Activity 9), he offers a further argument, which Currie and Ravenscroft do not consider. Imagery, White writes, ‘does not express anything, whereas imagination does’. Here most of all, perhaps, we can see that what White is concerned to describe are the differences between merely having an image and imagining. Take his example of an image of a sailor on a beach. This could be interpreted as a sailor scrambling ashore, his twin brother crawling backwards into the sea, or any of a host of other things. Imagining that a sailor is scrambling ashore, then, cannot consist in having such an image. We can agree with White on this. But it does not follow that having such an image is not an essential part of the imagining, which is the issue at stake as White himself formulates it (in the fourth paragraph of the first White extract). What turns the mere having of an image into imagining is what we do with that image – the role it plays in our thinking. This is what Currie and Ravenscroft mean when they talk of imagery being a form of imagination. It is acts of producing and using images that constitute one form of imagining, and images are of course essential in this.