The range of work with young people

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 19 April 2024, 10:21 AM

The range of work with young people

Introduction

In this course we will be looking at the range of settings within which practitioners work with young people. Some people reading it will have experience of working with young people in at least one setting. Others may have a more general interest in young people and may have begun to think about the ‘spaces’ within which they spend their time, and the different ways that they might be supported. Settings are diverse and include schools, youth or community centres, voluntary movements such as Girlguiding, faith-based projects, education or training related projects, those linked with arts or sport, and, importantly, the street. You might be aware of organisations that work with people of all ages but wish to acknowledge the particular contribution of young people. Alternatively, you may have experience of spending time with young people in a residential setting – with looked after children, a youth offending institution, summer camps or within your own family home as a parent or foster parent. This course highlights the importance and variety of the ‘spaces’ that young people frequent and the nature of their relationship with the adults that they meet. As we progress through the course you will have the opportunity to focus on settings with which you are familiar, as well as The Factory Project – just one example of the range of work with young people.

The first part of the course outlines some features that we might use to describe the settings where work with young people takes place. This encourages us to notice and reflect on the similarities and differences between settings.

We follow this with various perspectives that can help us to reflect on these settings and thus understand more about the experience for young people and workers. We then move on to look at a number of examples of different settings for such work, aiming to relate the theoretical ideas to the realities of practice. We conclude the course with an activity that invites you to analyse a setting of your choice.

Fundamental to the course, and to thinking about work with young people, are the ideas of description and reflection. We begin, then, with a brief explanation of these ideas.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of level 1 study in Education.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand the distinction between description and reflection

describe the range of work with young people and the variety of organisations, settings and working practices that this encompasses

compare and contrast work in a range of settings, using a set of parameters such as: location, type of organisation, aims, funding, worker roles

illustrate examples based on personal experience or that of friends or family.

1 Describing and reflecting

One of the central ideas in work with young people is that of reflective practice. We try to reflect on our practice as teachers, and we want you to reflect on the practice of workers with young people – both your own practice (if this applies to you) and that of others.

In practical terms, you will often be asked in your assignments to describe and to reflect. The most important point to make about this is that ‘describe’ and ‘reflect’ are actually ordinary, everyday words referring to familiar and straightforward processes – they are not specialist or technical terms. Neither is very precise, but they do not need to be. Their basic meanings are captured succinctly by ordinary dictionary definitions (in this case from The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary):

- describe: to set forth in words by reference to characteristics … to represent, picture, portray

- reflect: to turn one’s thoughts (back) on … to ponder, meditate on.

Thus, description answers straightforward factual questions, such as:

- What is it?

- What happens?

- Where and when does it happen?

- How big is it?

- Who is involved?

As an example, here is part of a description of a youth centre in Glamorgan, South Wales:

Cowbridge Youth Centre is a statutory full-time youth provision operated by the local education authority. It is situated in a prosperous medieval market town …

The youth centre is situated off the main street behind the police station in a former magistrates’ court. It is a single-storey building with several rooms for different activities, including a hall for discotheques, band practice, pool, table tennis, etc.

Opposite the centre are public playing fields; the town also has a small leisure centre but it is in a rural location with little public transport at night connecting the outlying villages. Young people rely heavily on transport from parents to attend the youth centre.

The youth centre offers provision for young people aged 11–25 years, but the majority of users are 14–16 year olds.

Reflection is required in response to questions that are less straightforward, involving thinking about reasons, motives, values and judgements, such as:

- What is the purpose of this activity?

- What values and principles are being followed?

- How and why do young people get involved?

- What do they (and the workers) get out of it?

- What seems successful, and less successful, in what is done – and how should we judge?

- What might be done differently?

As an example, here are some reflections on work with young people by Jack Provan, an RAF engineer who works with young people on a voluntary basis, who is also an Open University student. He is reflecting on how different conceptions of rights and responsibilities influence this work.

While studying E131 and E118 over the last few years I have read about and met people who work for a number of projects and organisations who ensure Young People are aware of the rights that they have. These include things like housing and rights to benefits. I was wondering how many projects out there that assist Young People with understanding these rights also help them understand their responsibilities as members of society, and how those responsibilities are defined? …

For instance I was working with a group of young men who were playing football in the park during a break in the day’s programme. The language was pretty bad and we as the workers couldn’t get them to tone it down. There was a gentleman nearby who was playing with his toddler who was fairly disturbed by our group and ended up leaving the area.

On discussion with my Line Manager I put the point across that the group had a right to use the park but also a responsibility to cause as little distress to others when using public spaces. … My Line Manager on the other hand suggested that our group were present first and the gentleman with the toddler chose to stop beside us. The rest of the park was empty so should our group have to modify legal behaviour because of the choice of this one man?

It made me realise just how much my values impact on my practice, which brought me to thinking about how we define responsibilities when we talk to Young People. I obviously feel that the Young People have different responsibilities than my Line Manager does and it made wonder how in the future I can define my practice.

Jack’s reflections arise out of a specific incident in his work with young people. Among other things, it leads him to reflect on the purposes of this work. He recognises that the work is widely seen as being about (informal) education of young people in their rights, and wonders whether it neglects their responsibilities.

It also leads him to reflect on values, thinking about the relationship between values and practice, and about possible tensions between his personal values (concerning how to behave in public and how to treat other people) and the values of the organisation for which he is working. These are personal issues for Jack in his particular work situation, but they have wider relevance and application too.

The example above shows Jack reflecting mainly on his own work but, of course, we can reflect on other people’s work too, as you will be doing in this course.

2 Describing practice

We start our description of practice by highlighting three issues that provide a background to our discussion. These issues demonstrate that work with young people is not a fixed concept which looks the same everywhere that it takes place.

- First, you may already be aware that what we call ‘work with young people’ takes place in a wide range of different settings. This can be exciting as it might alert you to possible opportunities that you have not previously come across. It can also be confusing as you may start to wonder what these different ‘settings’ have in common and whether any general conclusions can be drawn.

- Secondly, there are differences in the work between different localities, for example, differences between urban and rural work. In particular you may notice differences of approach between different countries, such as the UK and the Republic of Ireland, and between the nations of the UK – England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Governments within the UK have become increasingly devolved, with local decisions being made about issues such as education or health provision, and this means that work with young people sometimes varies in emphasis within these different nations.

- Thirdly, work with young people changes over time. This might be due to different expectations of young people within society or changing understandings of their needs and interests. Work with young people can be seen at different times as a way of managing their behaviour, providing a safe environment within which they can prepare for their role in adult life, or offering a means of support into or through faith. As we write this course, the context for work with young people continues to change. A change of government can bring new priorities, but so too can other events. For example, funding for work with young people is being reduced at the time of writing due to austerity measures, and increasingly being concentrated on targeted work with young people.

These three issues suggest that work with young people is always ‘contextual’. The practice in detail relies on the particular setting, location and time within which it takes place. However, despite these differences, all of the settings that you are likely to encounter share a concern for the welfare and well-being of young people and, because of this, it is possible to draw out some principles that you can apply to situations with which you are familiar.

The first activity in this course aims to help you to build on your current awareness of this diversity by searching the internet to see what is available in your local area and comparing it with the range of facilities in another area of your choice.

Activity 1: Finding out about youth settings through the internet

The aim of this activity is for you to use the internet to find out what kinds of settings might be available for young people in your local authority area. First of all, find the website for the local authority that provides services for young people in your area. This is often a unitary, city or county authority rather than a very local district authority. You can usually find the website quite simply by typing the name of the authority into a search engine. Once you have the front page of the website for your local authority, type ‘youth’ into the search box (you can also try ‘young people’ if using ‘youth’ does not seem to reveal much) and see what links it comes up with. When we did this we found links such as youth offending, youth and connexions service, youth centres, and voluntary youth work. Click on any links that look interesting or useful and see what information you can find about the kinds of settings that are promoted on this site. If you have time we would also recommend that you try two more activities:

- Repeat the exercise with a neighbouring local authority so that you can compare and contrast the settings within the two areas.

- Try the exercise again with a search that uses words such as ‘young people’, ‘adolescent’ or ‘teenage’.

There is a great deal of variety among local authorities both in the availability of services for young people and in the design of their websites. If you do not find very much information from your own local authority website, it might be useful to compare it with that of a neighbouring authority, or some other authority known to you.

Make a note of your findings.

Discussion

When we carried out this exercise towards the end of 2012, we searched on the website for Ealing Council in West London. The following link takes you to the results of our search for the word ‘youth’.

Our search provided links to the youth and connexions service, youth offending, youth centres and voluntary youth work (among others). When we explored youth centres further we found descriptions of different centres with a wide range of activities. Here are two examples that we found at the time of writing. These may have changed – they may even have ceased to exist – by the time you read this, but they illustrate the kind of information that you can obtain from an internet search.

Bollo Brook Youth and Connexions Centre

This is a statutory youth centre in the South Acton estate that specialises in arts-based youth activities. Boasting extensive recording studio facilities and quality film-making and photo-editing equipment, it is used for a wide variety of projects with young people. This specialist work is complemented by an extensive programme of socially educative, recreational, and advice and guidance-based activities. The centre is also used for daytime programmes with young people who are not in mainstream education, delivered in partnership with other voluntary and statutory sector organisations.

W13 Youth and Connexions Centre

The centre focuses on inclusion work, providing a varied weekly programme including a session for young women and a music production and dance session. It also offers fashion and textiles for aspiring fashion designers. It is the base for the service’s disability project; the project develops opportunities for young people with disabilities and provides support to individuals and groups.

We also explored the ‘Youth and connexions’ link and found a page on youth projects. We found these for example:

Duke of Edinburgh’s Award (DofE)

DofE offers young people a challenging adventure that is rewarding, fun and exciting. They will be able to meet new people, learn new skills, develop physical fitness and make a difference to their community. They can undertake programmes at three levels: accredited bronze, silver and gold awards. Gaining the DofE’s award can benefit young people’s employment prospects and assist applications to college and university.

Horizons Education and Achievement Centre

Horizons is part of Ealing social services’ Leaving Care programme in partnership with Ealing Youth and Connexions Service. The centre offers young people in care, and those who have recently left care, a ‘safe space’ where they can get support whilst in the process of leaving care. In an informal and relaxed environment young people can share experiences, and seek information, help and advice in order to plan and prepare for independent living.

Participation project

The Participation project leads in developing the service’s work in young engagement – where young people can influence decisions made about future services – by involving them in the democratic processes. It has worked with and supported young people to develop Ealing Youth Action, the borough’s youth forum, representing the voice of young people. Young people can also champion the views of their peers by becoming the Youth Mayor and national representatives at the UK Youth Parliament.

Your Zone

Your Zone provides a safe space for young people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or unsure of their gender or sexual identity to meet and socialise. It runs programmes to enable young people to develop the skills to make informed decisions and choices, and offers one-to-one information, advice and support.

At the time of writing there appears to be plenty going on in Ealing – there seems to be a lot of provision and the council organises their site in a user-friendly way. We looked on a number of different council sites and they were all very different, so don’t be disheartened if your chosen site appears to bring up less information. We suggest that you try looking at a variety so that you get a clearer idea of what is on offer in different places. Sometimes we felt the activities on offer reflected a ‘local’ flavour. For example, Bristol links youth and play while in Edinburgh youth activities are linked with ‘Community Learning and Development’ and Cardiff has a link to ‘Welsh youth work’.

This activity, of course, tends to show mainly the facilities and services provided by the local authority. For example, the Ealing site’s ‘voluntary youth work’ link simply directs us to information on how to become a voluntary youth worker – it does not tell us anything about young people’s activities that are provided voluntarily. If we could see the whole range of settings and facilities in more depth it is likely that there would be even more variety as it would include private youth organisations, those within the voluntary sector and those linked with faith-based organisations. If you are interested you may like to try searching for some of these but we suspect that this will be a more complex activity because of the range and diversity of such organisations.

In the second part of the activity we suggested searching using different words to represent ‘young people’. If your experience is similar to ours you will find that a new set of links appears when words such as teenage or adolescent are typed into the search box. This activity gives a practical example of the different ways in which words can be used to shape understanding. We suggested initially searching using the word ‘youth’ because on most sites that seems to produce a wider range of activities for young people. When we tried searching using the words ‘young people’ some of the sites directed us to sites for ‘children and young people’ apparently as a generic grouping – and much of this information was about policies rather than activities. ‘Adolescent’ and ‘teenage’ produced a further group of links. The first of these often directed us to mental health sites – this seeming to be the preferred terminology in health and psychology as it suggests a ‘developmental phase’ of human life. The second seems to be primarily used in relation to ‘teenage parents’ – possibly to emphasise the relative youth of this group.

‘Family resemblances’ between practices

As the previous activity illustrates, there are a lot of widely different activities and services available for young people. Might they be too diverse to be considered under one umbrella term of ‘working with young people’? How would we recognise ‘work with young people’ when we see it? And what assumptions, if any, can we make about it when we do see it?

This is a difficult and much debated question. One way of looking at it (discussed in Banks, 2010) is to think of work with young people as a ‘family of practices’. This is a development of an idea from the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein argued that many ordinary, everyday words are difficult to define, but that does not mean we do not understand them. He took as his example the word ‘game’.

Consider for example the proceedings that we call ‘games’. I mean board-games, card-games, ball-games, Olympic games, and so on. What is common to them all? – Don’t say: ‘There must be something common, or they would not be called “games”’ – but look and see whether there is anything common to all. – For if you look at them you will not see something that is common to all, but similarities, relationships, and a whole series of them at that. To repeat: don’t think, but look! – Look for example at board-games, with their multifarious relationships. Now pass to card-games; here you find many correspondences with the first group, but many common features drop out, and others appear. When we pass next to ball-games, much that is common is retained, but much is lost. – Are they all ‘amusing’? Compare chess with noughts and crosses. Or is there always winning and losing, or competition between players? Think of patience. In ball games there is winning and losing; but when a child throws his ball at the wall and catches it again, this feature has disappeared. Look at the parts played by skill and luck; and at the difference between skill in chess and skill in tennis. Think now of games like ring-a-ring-a-roses; here is the element of amusement, but how many other characteristic features have disappeared! And we can go through the many, many other groups of games in the same way; can see how similarities crop up and disappear.

And the result of this examination is: we see a complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing: sometimes overall similarities, sometimes similarities of detail.

I can think of no better expression to characterize these similarities than ‘family resemblances’; for the various resemblances between members of a family: build, features, colour of eyes, gait, temperament, etc. etc. overlap and criss-cross in the same way. – And I shall say: ‘games’ form a family.

Similarly, Sarah Banks argues that even if there is no one feature or set of features that is common to all the practices that we might call youth work, these practices have a ‘family resemblance’ (2010, p. 6) of the kind Wittgenstein described. In this course, we will be looking at a ‘family’ of types of work with young people. These will have a variety of names and at times we may find it difficult to define characteristics that they all have in common. However, we will readily find the kinds of overlapping and criss-crossing similarities about which Wittgenstein and Banks write.

The next section starts to look more closely at the range of settings where work with young people takes place and to suggest ways in which we might describe these settings – taking into account the similarities and differences that will arise within a ‘family of practices’. In this way, we will continue to develop our ability to recognise and discriminate between the different kinds of provision on offer to young people.

Examining diversity

By now you will be aware that work with young people uses a variety of locations. However, you will also recognise that the diversity of settings is not simply about the building or other facility within which the work takes place. The difference between ‘settings’ might be represented in terms of a number of features that we can use to describe them:

- the location of the work

- the organisation that is responsible for the work

- the type of work that takes place there and its aim

- whether provision is part time or full time

- the role of the person/people doing the work

- employment arrangements – whether work is paid or unpaid, for example

- whether the setting receives funding and/or charges fees

- whether the setting needs to report to anyone else about what it does.

The next activity asks you to look at The Factory Project in the light of the features we have just listed.

Activity 2: Analysing a practice setting

To carry out this activity, you will look at two audiovisual ‘clips’ illustrating the work of ‘The Factory Project’, a youth work project in Loughborough, Leicestershire.

It is a detached youth work project for Asian young men who live locally. It aims to work with those aged 11–25 years of age, but with 80% of time and resources going to work with 13–19 year olds. The project was established in 2000 and aims to increase the active participation of Asian young men in the work of the Youth Service. It was founded by two detached youth workers and a small group of young people who met at a derelict warehouse, which gave the group its name.

The Factory Project seeks to:

- create space for young people

- provide opportunities

- establish challenges

- develop potential

- unleash creativity

- broaden horizons.

To do this the young people have taken part in lots of activities including discussions, debates, campaigning, health education workshops, outdoor pursuits, camping, visits to museums and places of interest, film-making and so on.

The first clip shows one evening’s work and in the second, Andrew, who manages the project, explains how he views it. In these clips, as well as Andrew, we see two part-time workers on the project, Akkas and Kasem. They were both originally participants in the project as young people.

As you watch, note down how you would describe the setting in terms of the features listed earlier in this course. You might find it helpful to use a table like the one below. (We have filled in our thoughts about the first feature to show you what we mean.)

(The content within Activity 2 including the videos is not subject to Creative Commons licensing.)

Transcript: The Factory Project clip 1: An evening with The Factory Project

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

[JAHANGIR RAPS]

Transcript: The Factory Project clip 6: Andrew’s perspective

[SIDE CONVERSATION]

[SIDE CONVERSATION]

| Feature | The Factory Project |

| The location of the work | The Factory Project takes place mainly in the street environment. |

| The organisation that is responsible for the work | |

| The type of work that takes place there and its aim | |

| Whether provision is part time or full time | |

| The role of the person/people doing the work | |

| Employment arrangements – whether work is paid or unpaid, for example | |

| Whether the setting receives funding and/or charges fees | |

| Whether the setting needs to report to anyone else about what it does |

Discussion

When we did this activity we filled our table in as follows:

| Feature | The Factory Project |

| The location of the work | The Factory Project takes place mainly in the street environment. |

| The organisation that is responsible for the work | The Factory Project is a project funded by the local authority. |

| The type of work that takes place there and its aim | The Factory Project aims to offer opportunities to, and raise the aspirations of, a group who make less use of youth provision than some others. |

| Whether provision is part time or full time | The project works at different times of the day and week to fit in with the lives and routines of the young people. |

| The role of the person/people doing the work | Andrew and his team are trained as youth workers. |

| Employment arrangements – whether work is paid or unpaid, for example | There appear to be paid and unpaid opportunities within this setting. It aims to ‘grow its own’ workers and train young people who participate. |

| Whether the setting receives funding and/or charges fees | The Factory Project started with a tiny budget but has succeeded in obtaining a large grant for a building. |

| Whether the setting needs to report to anyone else about what it does | The project carries out evaluation and it also needs to report to those who give funding. |

You and other readers of this course may have experience of different types of settings where there are different expectations. For example, some of you may spend time with young people primarily on a one-to-one basis, whereas others will work in group settings. Some of you may work with particular young people ‘targeted’ because of their perceived needs or problems, others will work in settings where young people can come and make use of the facilities during their leisure time. Some may work in youth clubs or centres, while others might engage in ‘detached’ work with young people on the streets.

An important distinction between settings concerns how much money they have to pay for activities and where it comes from. For example, funding may come predominantly from fees contributed by participants; alternatively, the setting may receive money from external sources such as the government, a charitable trust, donations from the public, or some mixture of all of these.

Often when a setting receives funding from an external source this means that those within the setting are required to work in a specified way (with particular young people, for example) and report to their funder on how successfully they have achieved this.

Readers of this course will also reflect the diversity of the sector through different patterns of engagement with young people. For example, if we consider employment patterns, there are many possibilities:

- you may be working with young people on a voluntary basis, with an organisation such as The Scout Association or St. John’s Ambulance. If so, you are likely to have other activities (such as work or domestic responsibilities) that occupy you for the rest of your time

- you may be working young people as a part of a different role – such as being a police officer or a firefighter

- you may be in the early stages of a career with young people

- you may not be working directly with young people at all but meeting them as part of the family or the local community.

Such differences in personal interest and outlook will affect your expectation of a setting and the setting’s expectations of you.

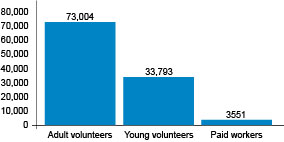

Interestingly, there is limited recorded evidence about the numbers of practitioners (paid and unpaid) who work with young people or the nature of what they do. Statistics that are available tend to measure certain parts of the sector. For example, YouthLink has measured the contribution made by different categories of worker to voluntary youth organisations in Scotland. These volunteers and paid staff work with a total of 386,795 young people, though the age range is wider than the 13–19 group that we are concentrating on in this course (37 per cent are under 10, 31 per cent are aged 10–14, 24 per cent are aged 15–17 and 8 per cent are aged 18–24.)

This is a histogram showing the numbers of people in the different categories of worker in voluntary youth organisations in Scotland (2012 data): Adult volunteers (aged 25 or over) = 73,004; Young volunteers (aged 16–24) = 33,793; Paid workers = 3,551.

‘Adult’ volunteers are defined by YouthLink as those over 18 and ‘young’ volunteers as those under 25 who have helped on a short-term basis. What emerges clearly is the importance of voluntary workers to these organisations.

A similar picture emerges in other parts of the United Kingdom. In Northern Ireland:

there are at least 27,703 individuals involved in delivering and supporting youth work in Northern Ireland. This is more than the number involved in either the energy & water, or agriculture, forestry and fishing, sectors, in [Northern Ireland].

Within this workforce, 90 per cent are volunteers, most of whom are engaged in uniformed or church-based youth work; 8 per cent are part-time paid staff and 3 per cent are full-time paid staff.

In England:

The most recent figures suggest that there are around 5,500 [full time equivalent] youth workers employed by churches and Christian agencies, more than the statutory youth service … . There are also said to be around 100,000 volunteers. Churches have become the largest employer of youth workers in the country.

Overall, these statistics demonstrate that there are a large number of people who spend at least part of their time working with young people. However, the statistics are still incomplete. The next section concerns an attempt to audit a wider range of activity with young people in England.

The CWDC audit of work with young people

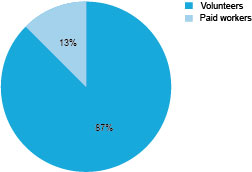

In 2009, a survey of those who work with young people was carried out in England by the Children’s Workforce Development Council (CWDC, 2009) – an organisation whose work has now been taken over by the Department for Education and the Children’s Improvement Board. The 2009 audit identified over 6 million workers working with young people, divided between volunteers and paid workers (as shown in Figure 2).

This is a pie chart showing the percentages of volunteers and paid workers

who worked with young people in England in 2009: 13% were paid workers and 87% were volunteers.

Once again, the audit shows the scale of the work that takes place with young people on a paid and unpaid basis.

The largest sectors of paid workers were in sport and recreation, health, play work and youth work. Of these, around two-thirds of youth and community workers, two-fifths of sport and recreation/outdoors workers and one-third of play-work staff work full time (CWDC, 2009), reflecting the potential of work with young people as a possible career option. However, as in Scotland and Northern Ireland, the great majority of workers were volunteers, reflecting a long tradition of this kind of work.

The next activity uses the framework developed as a result of the CWDC audit to help you to start to locate yourself within the bigger picture of those who work with young people. The CWDC framework is just one way of ‘cutting the cake’ and dividing work with young people into categories, but we hope it is one you find illuminating.

Activity 3: Locating your work in the bigger picture

Look at Figure 3, which was produced by the CWDC audit. You will see that it is divided into different segments and also different shades. The darker sections describe front-line practitioners with young people – that is, people who usually work face to face with young people and who are described by the CWDC as the ‘core young people’s workforce’. The lighter sections illustrate those people who spend some of their time working with young people and some (perhaps more) with other people – described by CWDC as the ‘wider young people’s workforce’. For example, a community musician might spend some of her time working with older people, families or younger children and some of her time working with young people.

This diagram is described in the unit text as showing one way of ‘cutting the cake’ and dividing work with young people into categories. It is a circle, divided into 12 segments or ‘slices’, with each segment representing a different area of work with young people.

Each segment is divided into an inner section (darker in shade) representing the ‘core’ young people’s workforce, i.e. those who usually work directly with young people, and an outer section (lighter in shade) representing the ’wider’ young people’s workforce, i.e. those who may spend some time working directly with young people, but who also spend much or perhaps most of it working with other adults.

The segments are as follows, with examples of ‘core’ and ‘wider’ workers for each.

Education and schools

Core: Connexions, education welfare and attendance, learning mentors, extended schools staff, school library staff

Wider: Family support advisers

Housing

Core: Housing and accommodation support workers

Wider: Housing advice workers

Playwork

Core: Assistant playworker, playworker, play ranger

Wider: Play work manager, play development worker

Social care

Core: Community workers, leaving care workers

Wider: None

Youth justice

Core: Youth justice, youth offending teams, staff working in secure estates

Wider: Police in school liaison and child protection roles

Youth work

Core: Youth workers; youth support workers; information, advice and guidance workers; youth workers in voluntary, community or faith sectors

Wider: Administrative staff in youth centres

Substance misuse

Core: Substance misuse, outreach worker, young people’s drug health worker

Wider: Young people’s substance misuse strategy co-ordinator

Sport and recreation

Core: Coaches, fitness and other instructors, activity leaders, lifeguards

Wider: Spectator control, studio/duty managers, sport and club development officers

Volunteers

Core: Scout leaders, Guide leaders, sports and activity leaders

Wider: Management committee member, board trustee

Outdoors

Core: Activity leader, instructor, tutor, trainer, programme leader, practitioner, facilitator, expedition leader

Wider: Residential sites – facility manager, head of centre

Health

Core: Psychotherapists, psychiatrists, school nursing teams, community paediatricians, teenage pregnancy workers, CAMHS (Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services)

Wider: Nutritional therapists, art therapists

Creative and cultural

Core: Arts, cultural heritage workers, choreographers, dance teachers, music teachers

Wider: Community musicians, entertainers

Identify where you and your work might fit within this wheel.

- If you work with young people, see if you can identify the sector within which your work might be placed – such as health, youth work or youth justice.

- If you have identified a sector, now think about whether you would place yourself within the darker blue section of core practitioner or the lighter blue section of ‘occasional’ worker with young people.

- If you don’t currently work with young people, consider roles that you have had in the past or places that you went to and services that you used as a young person. Are you able to place those on the wheel?

- If you work with young people or would like to, think about where you might like to be on this wheel. You might be happy where you are or you might aspire to a different role.

Make a note of your answers in the box below.

Discussion

You may be surprised at this range of work with young people – or you may be experienced in this field and feel that you are familiar with at least some of the different sectors. You may already be thinking about the similarities and differences between the work in different parts of the wheel. We will continue our discussion looking at different ways of understanding these. Note that some people who ‘work with young people’ have been omitted from this wheel and were not included within the audit. This includes, for example, people providing formal compulsory education, or post-16 education or training, and social workers. This is because our primary consideration here is work with young people and ‘informal education’ which we will examine more closely in the next section.

3 Reflecting on practice

So far, we have been describing the range of work with young people; now we are going to reflect on it. You may wish to remind yourself of the distinction between description and reflection set out in Section 1. As you will recall, a description tells us what something is like, answering straightforward factual questions. We have just been looking at such factual questions as, ‘How many people are involved in work with young people?’, ‘Which sectors do they work in and which organisations have they worked for?’, and ‘Were they volunteers or paid staff?’ – and so on.

Reflection was defined (following the dictionary) as ‘to turn one’s thoughts (back) on … to ponder, meditate on’. It answers more complex questions, concerning reasons, motives, values purposes and judgements.

So far, then, we have looked principally at ways in which we might identify and describe practice settings. The next, more reflective, part of our discussion begins by attempting to discover some patterns within these settings.

Informal education

We start our reflections on practice by considering some of the similarities that tend to occur within settings where work with young people takes place. So far in this course we have identified some of the places where young people spend time. We have also differentiated the settings that we are concerned with – such as youth centres – from those whose principal aim is to provide formal education – such as the classroom. The places and spaces that we are concerned with in this course are often places and spaces where young people choose to attend or where they have some time that is relatively free of ‘obligations’. A great deal of learning can happen within these environments, and this type of practice is often known as ‘informal education’. Informal education has been characterised by Tony Jeffs and Mark Smith as ‘the learning that flows from the conversations and activities involved in being members of youth and community groups and the like’ (Jeffs and Smith, 2005, p. 5).

Janet Batsleer describes it more fully as follows:

‘Informal Education’ is an educational practice which can occur in a number of settings, both institutional and non-institutional. It is a practice undertaken by committed practitioners. It may also be engaged in – at the margins of their activities – by other professionals, such as teachers, nurses and social workers. Most professional informal educators are not described in this way in job titles or job descriptions. Instead, job titles are associated with a particular client group. Common terms include: community education; community learning; lifelong learning; mentoring; social pedagogy; popular education; youth and community work; project work and youth engagement.

The idea of ‘informal’ education as a practice is not meant to imply that ‘anything goes’ – it can be equally as purposeful as formal education. However, formal education (such as in school) is usually linked clearly with a ‘curriculum’ – a set of material that students are expected to cover in order to meet certain ‘learning outcomes’. This course is itself an example of such an approach with learning outcomes explicitly set out at the start.

All in all, it is how workers spend their time with young people that is important – having conversations, organising activities, celebrating achievements, listening to problems, sharing disappointments and offering supported challenges. Jean Spence suggests that a ‘particular type of commitment, and a personal ethic of service motivates many practitioners in their work with young people’ (Spence, 2007, p. 300). So whilst ‘doing things’ is important, there is a sense in which ‘being with’ young people is just as or more significant – the practitioner using their personality, interests, skills and moral sensibilities to engage with young people in meaningful relationships.

Through participation in such processes and activities, young people (and adults) learn about themselves, each other and the wider world. Here we note that these approaches emphasise learning within the context of a positive relationship and suggest that genuine relationships in which people are valued can, in themselves, support personal development and emotional discovery. This is not necessarily bound by setting; it does not need to take place in a particular type of organisation or building and is appropriate within a wide variety of contexts where practitioners or other adults spend time with young people. Whether informal education is the prime purpose of a job role or takes place, as Batsleer says, ‘at the margins of … activities’, it is always an important element of the time that is spent with young people.

Other aspects of work with young people

Informal education is central to work with young people, then, but it is not the only important feature. Other aspects of the work – such as social contact among young people and between young people and adults, and recreation and enjoyment – are surely worthwhile and valuable in themselves quite apart from any educational benefits that young people may derive from them.

There is one more important element that we would add to this. According to a youth policy document from the European Commission, work with young people also has a political dimension.

Youth work has an impact on young people’s life and helps them to reach their full potential. It contributes to their personal development, but also facilitates social and educational development. It enables them to develop their voice, influence and place in society.

In the following activity, we introduce two case studies and use them to apply the ideas that we have been examining.

Activity 4: Applying ideas to practice

We can summarise the main features of work with young people as four ideas (European Commission, 2012; Verschelden et al., 2009):

- informal education – personal development and learning from the everyday

- social contact with other young people and the wider society

- recreation and enjoyment

- development of voice and influence.

Read through the two case studies below and look for examples within each of the four ideas summarised above. Try to explain briefly how each point is illustrated within each case study example.

As you will see, the case studies are written in rather different styles – the first is more ‘academic’, the second is more ‘journalistic’. This reflects their origins in an academic publication and a broadsheet newspaper respectively.

Note that both examples include children and young people of different ages. However, both describe work with young people within a particular community – one in a hospital and the other in a large city.

Please make a note of your answers in the box below.

Case Study 1 – Hospital youth work

Research undertaken in a city hospital showed that many young people arrived at Accident and Emergency with symptoms of self-harm or overdose but, after the admissions procedure, did not wait to be treated. This was seen as a ‘cry for help’ which was going unheard. Feedback from young people was that they were being treated as ‘cases’ rather than as individuals. The report argued for a young person’s advocate to provide them with information and support during clinical encounters so that they were able to take responsibility for their health. Discussion led to the recognition that the hospital was too heavily focussed on medical intervention, failing to take account of the other issues in young people’s lives: their family situation, housing, emotional stability – and therefore, their ability or readiness to engage with medical professionals.

Three youth workers now form the Hospital Youth Work Team and, after initial cynicism about what was an untried approach, this has now become an integral part of the hospital’s service to young people. All young patients aged 11 upwards are contacted by youth workers. They offer support, information and activities, including taking young people out for a break, to the shops, or for a game of pool. Frequently they are involved intensively with young people who are distressed and fearful. Alongside such casework support, a central concern is to be advocates on behalf of young people, to ‘de-mystify’ medical language so that they can understand and be more actively involved in their own health care. The team runs training sessions with medical staff about communicating with young people, and about young people’s issues and perspectives.

Youth workers have made a significant difference within the hospital:

I can see the transition of the young people. They are healthier; they are taking responsibility for themselves; they are empowered; they are able to vocalise their views; elements of contentment/satisfaction in their lives – you can see that in the way they engage with professionals (Member of Hospital Staff).

Case Study 2 – Youth clubs: from boxercise to building

It’s 4:45pm and the Hunslet Club in south Leeds is so busy that I have to queue for quite some time to get in. Toddlers are racing around, parents drink coffee and kids in, variously, ballet outfits, gym kits and disco gear jostle to get past me.

It’s a typical Tuesday evening at the club, which has been running since 1940 in various guises, though never quite as actively as this. As enthusiastic chief executive Dennis Robbins, who has been with the club since 1970 when he was [a] 10-year-old, explains, ‘we now have a membership of 2,200, up from 200 when I joined’. …

The Hunslet Club is just one member of youth club charity Ambition, which has just changed its name from Clubs For Young People in a rebrand and refocus. Helen Marshall, Ambition’s chief executive, says the rebrand was important to raise the profile of clubs such as Hunslet: ‘The youth sector is a crowded sector but we are the UK’s leading youth club charity and we need to better advocate on behalf of our members.’

It’s doing this with a new three-year strategic plan … It’s also, thanks to a recent conference, Say Something, in which its young members helped shape the three-year plan, suggesting more business enterprise schemes, something the organisation now plans to promote.

In the case of Hunslet it’s not hard to see why the trumpet doesn’t get blown often. There’s simply no time. The energetic Robbins is far too busy teaching boxercise, ruffling small people’s hair and joining in with a hip-hop dance class to worry about proving the club’s worth. Nonetheless, its worth is evident. There’s an eye-watering timetable of clubs and classes, ranging from toddler ballet to City & Guilds courses in construction.

Serving the whole of south Leeds, the club is funded by Education Leeds to train local Neets (those not in education, employment, or training) and it works with 220 referred kids across the region. However, at the other end of the scale some of the provision is so good that kids travel from as far as York to use its boxing facilities. …

Clubs at Hunslet cost just £1.50 a pop, hardly a route to riches. So the facilities, 40 staff members and training are funded in an ingenious way. On weekends, the club doubles as a fully-licenced wedding venue and it also hires rooms out to private clubs through a private company, Hunslet Leisure Limited, which then gifts the profits back to the club.

Ambition works with clubs like Hunslet to provide training and support as well as funding (which in turn comes from business funding, charitable donations and smaller private donations). And the work it does is vital, says Marshall.

‘As much as 40% of voluntary youth clubs are in the most deprived areas of the UK,’ she says. ‘Attendance is voluntary and there’s a much more different dynamic than that in formal education. However, the relationship between a youth club and a school means that they can help each other.’

Discussion

Here are some of our thoughts about the two case studies.

Case Study 1 – Hospital youth work

Informal education – personal development and learning from the everyday

This takes place where the young person and the youth worker engage together in everyday learning related to the young person’s sense of well-being. Understanding what is happening to them now and what may happen in the future is of the utmost significance for the young person. The setting contributes to personal, social and emotional development as it helps young people come to terms with a difficult time in their life.

Social contact with other young people and the wider society

We can see that the presence of the youth workers gives opportunity for social contact and activity, and develops confidence in the young people – an attribute that will help them to form relationships and associate with others now and in the future. Young people will have a shared project of, sadly, being unwell in a strange institution and possibly hoping to ‘get better’. With support of the youth workers there may be opportunities to be ‘young together’ with other young people.

Recreation and enjoyment

This setting offers opportunities for recreational activities such as shopping and pool.

Development of voice and influence

The demystification of medical language helps the young people to understand and be more actively involved in their own medical care. There is evidence that they are able to express their views more readily.

Case Study 2 – Youth clubs: from boxercise to building

Informal education – personal development and learning from the everyday

It is difficult to be specific but it would seem that young people are encouraged to feel part of something bigger in this setting. Their needs and interests are being taken seriously as they are involved in planning, as well as taking part in activities and developing relationships with adults. This will help them to develop confidence and belief in themselves.

There are also opportunities for more formal learning where appropriate, sometimes in association with schools. The young people who are NEET (Not in Education, Employment or Training) attend the centre for training, and City and Guilds courses in construction are on offer. This is another example of informal and formal learning taking place alongside each other.

Social contact with other young people and the wider society

There seem to be plenty of opportunities in this setting for young people to meet others and for them to feel part of their local or wider community.

Recreation and enjoyment

Plenty of recreational examples are cited in the case study, with emphasis on boxing and different kinds of dance.

Development of voice and influence

Young people were involved in preparing the business plan for the club and suggested more enterprise activities. This gives them an opportunity to have a say in how the club runs.

In this section we have considered similarities between settings with young people to help us recognise these when we encounter them. In the next section we will look at some further ideas that will help us to consider the differences and contrasts between practice settings.

Different traditions and their influence today

One of the ways that we might differentiate between different types of work with young people is through consideration of the different traditions within the field. Bernard Davies describes a rich tradition of the development of work with young people throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. For example, he says of much early work with young people:

the emergent voluntary youth organisations could … be seen as pioneering an important new expression of the true philanthropic spirit. By self-consciously requiring their ‘workers’ to engage directly and personally with young people, they set out to bind giver and receiver very closely together. Indeed these highly personalised interactions were clearly seen as perhaps the carriers of the moral education to be achieved through youth work. From the very start therefore, and on the grounds that this was how its charitable mission was best conducted, ‘youth leadership’ placed ‘relationships’ at the very heart of its practice and provision.

However, Davies also describes how these ideals were usually driven by a variety of (sometimes competing) contemporary desires to reduce law breaking, increase femininity or manliness, civilise the working classes, develop faith or increase fitness for the military. Over the years provision and modes of working with young people have, as a consequence, developed differently depending on these different aims.

To help us see how different traditions of work with young people still exert an influence today, will be using a number of models. By a model, we mean a simplified, abstract representation of a complex reality, which attempts to concentrate on its essential features and show how they fit together.

The CWDC wheel that we looked at earlier is one such model. Let us note a few important things about it.

- It is a simplification of reality. Any of the categories it uses (‘outdoors’, ‘health’, ‘creative and cultural’ … ) cover a wide range of organisations and activities, but this model stresses what they have in common by putting them together.

- So, creating the model has involved making judgements and choices. For example, ‘outdoors’ could have been treated as part of ‘sport and recreation’ or ‘substance misuse’ could have been part of ‘health’ – but the CWDC decided to make them separate categories.

- Because of this, there are many different models that could be – and have been – made to help us to understand the range of settings that work with young people.

You may find, then, as the course progresses that each model has something different to say about settings for young people, and we need to know how we might make sense of that. It may help if we explain why we are using them. It is not because we feel that any one provides a correct or complete picture of how to visualise the work; it is because we believe that each of them in its own way helps us to think about working with young people.

It is also worth noting that no model is perfect, or beyond criticism – they may omit things that we find important or explain things in a way that we might dispute. You may already have found this with the CWDC wheel. However, they are there to be used and we can adapt them to suit our purposes and to make them more applicable to our own settings and ideas.

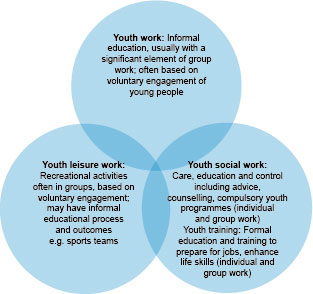

The next model that we will look at derives from the work of Sarah Banks, who suggests that, linked with the different traditions, there are three related ‘families’ of work with young people. We have adapted her diagram of these families in Figure 4.

This is a Venn diagram, with three circles that overlap a little, each representing a category (or ‘family’) of work with young people. The three categories, with descriptions of what they involve, are:

Youth work: Informal education, usually with a significant element of group work; often based on voluntary engagement of young people

Youth social work: Care, education and control including advice, counselling, compulsory youth programmes (individual and group work); Youth training: formal education and training to prepare for jobs and enhance life skills (individual and group work)

Youth leisure work: Recreational activities often in groups, based on voluntary engagement; may have informal educational process and outcomes e.g. sports teams

The circle on the bottom-left incorporates settings primarily associated with leisure activities, while the upper circle includes settings such as clubs that have an informal educational focus. Settings within both these circles tend to be open to all young people who choose to attend and are usually organised around group activity. However, whereas youth leisure often prioritises the activity and can treat young people as ‘consumers’, youth work is more likely to offer an activity as a ‘vehicle’ for building relationships. The bottom-right circle differs again as it represents settings for particular ‘targeted’ young people (those who are seen as more ‘in need’ perhaps), many of whom will not have chosen to participate. Work in this circle may concern a particular issue (such as health) and often takes place on a one-to-one basis.

Banks does not regard the three circles as representing straightforward exclusive categories but suggests that they incorporate overlaps. For example, sports teams (bottom-left circle) may be linked with a youth work setting (upper circle) or a youth work setting may on occasion work with an individual who is referred through the courts or social services (2010, p. 7), suggesting a link with the more targeted area of youth social work in the bottom-right circle. Similarly, a youth social care setting may take a group of young people on a residential trip that involves outward bound activity – an activity that appears to link more with youth leisure. Despite the presence of overlaps, a model of this nature can help us to understand the ‘family’ of practices termed ‘work with young people’.

Activity 5: Applying the three-circle model

Look back at your notes on Activity 1: Finding out about youth settings through the internet, and try to group the different settings that you found on your internet search within the three circles of the model in Figure 4. For example, participation within a local youth forum would fit in the top circle, whereas a swimming club would probably fit into the bottom-left circle and mentoring within a school into the bottom-right circle. Where the provision seems to fit in between categories make a note of this – perhaps this activity falls into an overlapping space. The aim of the activity is to start you thinking about different sorts of work with young people, with different aims and, perhaps, differing approaches and purposes.

As usual, make a note of your results in the box below.

Discussion

Using the three-circle model derived from Banks can help us to analyse the field of practice by dividing the different types of activity into groups which have some similarities. It helps us to identify sub-families within the ‘family of practices’. Inevitably, you will find that some might not fit or might fit into more than one circle. This can be useful to think about in itself, as it reminds us that things are rarely as simple as they appear at first sight – and we will see later on how the practice that takes place within the overlaps, and that recognises more than one tradition of work with young people, can be the most interesting and creative.

When you were looking on the internet at different settings and types of work with young people you may have noticed that it is not unusual for activities from each of the three circles in Banks’s model to take place in the same setting. They may even be happening at the same time. A practitioner may apparently move seamlessly from one to another while a young person involved might find it hard to distinguish between them.

Earlier, in Activity 4: Applying ideas to practice, we read an extract from an article (Davis, 2012) in the Guardian Professional, which described the work of the Hunslet Club, part of the national youth club charity Ambition. Now we can read some more of the article, as it goes on to describe some of Ambition’s other activities around England. It follows on from the claim by Helen Marshall, the chief executive of Ambition, that ‘the relationship between a youth club and a school means that they can help each other’.

To that end, some of Ambition’s clubs go into schools and provide programmes as part of the curriculum. It’s also working with the Department of Education for ways to help youth clubs to get disengaged children re-engaged and a pilot mental health project with Young Devon to prevent mental health issues from escalating.

Steve Crawley, youth programme development manager for Youth Action Wiltshire, agrees that youth clubs play a vital role that schools can’t always provide. Youth Action Wiltshire has 75 affiliated youth clubs and Crawley’s team, which works closely with the county’s integrated youth service, has recently been overseeing a project, Sowing Seeds, to turn scrubland into youth club allotments.

Conservation projects like this are a great way to involve young people, says Crawley, ‘They can see a difference in the work they do. They learn a lot of transferable skills and they learn how to work with each other. And also they’re using basic English and maths to measure out and mark.’

He mentions a kid he’s been working with who didn’t finish year 11 at school but through a project like this went on to complete an outward bound course at college: ‘Sometimes we lose the idea that youth clubs can be a great avenue for learning.’

In this excerpt we can see how settings within this organisation, which runs youth clubs, engage with mental health issues and schools. We also know from earlier activities that they provide leisure-based activities such as dance and some formal training in construction. This, then, is a demonstration of how different aims can be combined within the one setting.

However, by highlighting different approaches within the three circles we are encouraged to consider more closely the varying histories and traditions of these different ways of working with young people. These traditions can be strong and can be supported by many years of developing shared expertise in a particular way of working – what Etienne Wenger has called a ‘community of practice’ (Wenger, 1998). Examples of this include cooperative approaches in the Woodcraft Folk movement, working on the street in a ‘detached’ capacity or coaching within football clubs. Services or activities can be offered for different reasons and practice within the different traditions can encourage varying ‘images’ of the young people involved, different levels and types of funding, and different expectations of practitioners. These expectations will include training, knowledge and ways of approaching practice.

A young person who takes part in a boxing club, for example, may be seen as someone who will benefit from having an interest and taking part in energetic and perhaps diversionary activity. The adults within such a club are likely to be skilled boxers who may have attended the same club whilst young and have now trained as coaches. They may see their primary task as ‘instruction’, passing on what they have learned, alongside the development of self-esteem and confidence via achievement within the sport. In contrast, young people who receive services within youth social work may be seen as vulnerable or a threat – either to themselves or to those around them. The practitioners within such a service are likely to have two competing philosophies underpinning their approach – that of ‘care’, where the young person is seen as in need of ‘looking after’, and that of ‘control’ where the young person is seen as in need of ‘correction’.

Although it is not explicitly mentioned within the Banks model, many activities that involve young people will have a significant element of ‘playing’ attached to them – youth leisure and youth work both give opportunities for trying things out, for creativity and safe risk-taking. Meanwhile, youth training in the bottom-right circle and youth work in the upper circle (and to some extent youth leisure in the bottom-left circle) both share a tradition of education. However, as explained earlier, youth work emphasises informal education with its interest in personal development, self-identity and political awareness, whereas youth training tends to emphasise formal education, with instruction and an external curriculum.

A spectrum of youth work practice

Another model – or way of thinking about practice settings – to which Banks draws our attention is a spectrum of youth work practice.

This diagram shows the spectrum of youth work practice. At one end of the spectrum is ‘Universal (open access)’ youth work and at the other there is ‘Targeted’ youth work.

At one end of the spectrum there is open-access provision – open to all young people, who choose whether they will participate or not.

At the other end there is practice that is provided for specific young people – sometimes known as ‘targeted’ provision. Targeted work may be provided for named individuals who are seen as in need of particular support or intervention, such as youth offenders. Often, these young people have not chosen to participate.

The term ‘targeted’ is also sometimes used to describe services that are open to all but that are aimed at young people with particular interests or needs. These young people are likely to have made some choice to take part and we would therefore put these settings nearer the middle of the spectrum. Targeted work is often specialist in nature – for example it might involve specialist expertise in areas such as giving advice or counselling.

In the following section we consider how work with young people may be changing over time. Here, again, the spectrum model will be useful.

Changing understandings of work with young people

Within the UK, the 1990s and 2000s have seen considerable changes in work with young people. These changes have had varying emphasis within the different nations of the UK but many of the prevailing themes remain constant. Jason Wood and Jean Hine have related the development of changing practices to changing ideas about young people (Wood and Hine, 2013). Wood and Hine argue that under the Labour government between 1997 and 2010, government policy defining services for young people reflected two dominant understandings of young people.

- The first is that young people are prone to ‘risky’ behaviour. The idea of ‘risky’ behaviour encompasses, for example, youth crime, use and misuse of drugs and alcohol, or young parenthood. Wood and Hine suggest that ‘this concern with risky behaviour drives a desire to predict it and stop it’ and thus much practice with young people is aimed at prevention and targeted at groups that are deemed most likely to be ‘at risk’.

This label of ‘at risk’ is often used as a way of describing a generic group of young people (such as those who have few qualifications). It is not one that is necessarily used by young people to describe themselves and may not take into account the individual situations of particular young people (Smith et al., 2007). For example, within this perspective a young mother and her child are both seen to be ‘at risk’ of poor outcomes and the dominant view is that young motherhood is something to be ‘prevented’. However, any individual young woman may, in reality, be happy to start a family and may describe herself as a parent within the context of a loving relationship (Arai, 2010).

- The second dominant understanding of young people that Wood and Hine describe is that of ‘Dealing with young people for what they might become’. This view of young people sees them as needing to be prepared for adulthood, with this taking precedence over their lives here and now. It tends to see the activity of young people as being a kind of rehearsal for the real thing. For example, romantic relationships of young people may not be seen as important or as ‘genuine’ as those of older people.

This approach suggests an emphasis on the importance of training and education for young people, and can also be associated with encouraging broader preconceived notions of adulthood. These notions often assume that young people need to develop a ‘mature’ way of behaving (such as not drinking to excess) – whether or not this reflects the reality of the lives of many adults. We would argue that work with young people can see them as both ‘being’ and ‘becoming’ – with what they feel and do today being just as important as what they might do later in their life.

Mark Smith develops these themes in a discussion of work with young people throughout Great Britain. He argues that much work with young people in England has been influenced by ‘social work framework[s]’ (Smith, 2007) and has become more concerned with individuals and a focus on outcomes or pre-defined results. Much of the recent policy documentation in Scotland reflects similar concerns, concentrating on ‘specialised targeted provision designed to meet the needs of young people who are particularly vulnerable or who have specific needs’ (Scottish Executive, 2007, p. 4). Looking at Welsh policy documents, Smith acknowledges that this trend is less evident, but suggests that once again there is a strong emphasis upon the meeting of numerous targets. He would welcome more emphasis on the traditional encouragement within Wales of activities that are initiated by and within communities (Smith, 2007).

Taken together this evidence suggests that there is a general move in activity with young people, throughout Great Britain, toward the targeted end of our spectrum, with more emphasis on targeted programmes such as youth training or youth justice.

This has two possible consequences.

- First, a predominant view of young people as vulnerable or disadvantaged can be stigmatising and suggest that they are ‘lacking’ rather than having strengths that can be built upon.

- Secondly, universal and open-access provision – such as clubs and youth groups exemplified on the left of our spectrum – tends to be seen by policymakers as of reduced importance. Consequently, there is a loss of the types of settings for young people that are more concerned with the importance of ‘being’ – having fun, doing things, developing relationships and so on.

This diagram illustrates the shift towards targeted youth work practice. There is a large arrow underneath the spectrum of youth work practice (shown previously on page 36) pointing towards the ‘Targeted’ end of the spectrum.

The shift is most clearly seen within provision provided by the local authority and funded by the state (statutory provision), but can also occur within some voluntary-sector organisations where they rely on funding that supports the shift in emphasis. However, perhaps fortunately, some other voluntary organisations such as the Scouts and Guides that use voluntary workers and raise most of their own funds will be affected only marginally by such changes in policy.

At the time of writing (late 2012) there appears to be a popular and political interest in ‘positive’ activities in the UK – the London 2012 Olympics has increased interest in sport, for example – and the role of the voluntary sector is particularly emphasised. This suggests an increase in open-access provision on the left of the spectrum. However, funding is limited due to government cuts so there is likely to be less provision overall. Many services at the right-hand end of the spectrum are hard to cut because of legal requirements such as safeguarding. Consequently, it may be that cuts are implemented in the centre of the spectrum where provision has an element of targeting but is not ‘essential’, resulting in a shift of focus away from the centre towards both the left and right in the months and years to come.

A shift from state-funded to voluntary provision is in line with the idea of the ‘Big Society’ introduced by the coalition government that came to power in the UK in 2010, and associated personally with the prime minister, David Cameron. The Big Society is described on a government website as being about:

shifting the culture – from government action to local action. This is not about encouraging volunteering for the sake of it. This is about equipping people and organisations with the power and resources they need to make a real difference in their communities.

Throughout our communities there is a great appetite for involvement in local initiatives and people do want to make a difference in their area.

Mr Cameron insists that the idea is not, as some critics claim, ‘a cover for cuts’. He argues that it is of value in itself, though of particular benefit at a time when cuts in spending are being made.

It is not a cover for anything. It is a good thing to try and build a bigger and stronger society, whatever is happening to public spending. But I would make this argument: whoever was standing here right now as Prime Minister would be having to make cuts in public spending, and isn’t it better if we are having to make cuts in public spending, to try and encourage a bigger and stronger society at the same time? If there are facilities that the state can’t afford to keep open, shouldn’t we be trying to encourage communities who want to come forward and help them and run them?

The final activity in this course invites you to introduce a setting that you are familiar with and to consider how you might locate it within this discussion.

Activity 6: Analysing practice settings

This activity encourages you to think more deeply about your own practice setting, or one with which you are familiar. It is an opportunity to analyse your chosen practice setting. In order to help you with this we will bring together the principal descriptive and reflective ideas that we have discussed throughout the course.

First, let us recall the main descriptive features that we identified in Section 1 as characterising work with young people:

- the location of the work

- the organisation that is responsible for the work

- the type of work that takes place there and its aim

- whether provision is part time or full time

- the role of the person/people doing the work

- employment arrangements – whether work is paid or unpaid, for example

- whether the setting receives funding and/or charges fees

- whether the setting needs to report to anyone else about what it does.

Then we can move on to ideas that help us to reflect on the work. In Section 2 of this course, we introduced four ideas that appear to be common to work with young people across a range of settings:

- informal education – personal development and learning from the everyday

- social contact with other young people and the wider society

- recreation and enjoyment

- development of voice and influence.

Alongside these common features, however, there are differences, which are captured in two models that we presented:

- the three circles of youth leisure, youth work and youth social work and training (see Figure 4)

- the spectrum from open access to targeted provision.

This activity is a revision exercise for the course, but one in which you are involved actively and creatively, by applying the ideas to practice. We hope that it will help you to develop your thinking a little further, and perhaps raise questions and issues that you can share with colleagues in your tutor group or on the tutor-group forum.

Think about a setting for work with young people that you are familiar with. We have provided a list of questions to help you to describe and analyse this setting in relation to ideas that we have discussed within this course.