Voice-leading analysis of music 3: the background

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 26 April 2024, 2:30 PM

Voice-leading analysis of music 3: the background

Introduction

This course analyses the ‘voice leading’ of the harmony. The method of going about this kind of analysis is applicable to any piece of tonal music. Just as Mozart's piano sonatas are an excellent source of examples for studying the voice leading at the foreground and middleground of the harmony, so Beethoven's Eighth Symphony is also an ideal work in which to start to consider the largest-scale stage of voice-leading analysis.

This course requires you to switch between several different formats of material. This reflects the particular nature of analysis, where you are constantly comparing what you write out, or see in the score or analytical graph, with what you can hear – a difficult job! So make every effort to work through these materials in the manner and order suggested.

Please note that you should have studied OpenLearn courses AA314_1 Voice-leading analysis of music 1: the foreground and AA314_2 Voice-leading analysis of music 2: the middleground before attempting this course.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 3 study in Arts and Humanities.

The materials upon which this course is based have been authored by Robert Samuels.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

describe the nature of the background structure of a piece of tonal music

understand the difference between analysis which is definitely right or wrong and that which is dependent on individual judgement

relate the notes of a background graph and the indications of bar numbers to specific events in the musical score

understand the sorts of decisions and observations that go towards analysing the background structure of a piece of music

recognise the analytical statements about the various parts of a piece of music that are contained in a background graph.

1 Voice-leading analysis of form

1.1 Identifying the background level of the harmony

If you have studied OpenLearn course AA314_2 Harmonic analysis: the middleground you will already have been introduced to the general topic of the background, after the foreground and the middleground levels that you studied in your analysis of Mozart (OpenLearn course AA314_1). This is what one might equally call analysis of ‘form’. The present course, though, will focus on the way that musical form is created from the harmony of the music.

For the time being, I don't want you to think about how to divide up each movement into sections such as ‘exposition’, ‘development’, and so forth. These sorts of labels are important in studying a piece of music, and I will discuss how they relate to harmonic structure at the end of this free course. But first, I want to look at harmony on its own.

In the earlier courses, you saw that the rules that govern how one chord leads to another at the foreground of the music can also be seen to work over longer spans. These voice-leading rules prolong main harmonies as middleground structures. In this course I am going to consider how certain harmonies – that is, certain chords and melodic lines – similarly become the main harmonies for much longer spans of time, ultimately covering the whole of a movement.

I'll begin with the passage of music that was analysed more often than any other in OpenLearn course AA314_1.

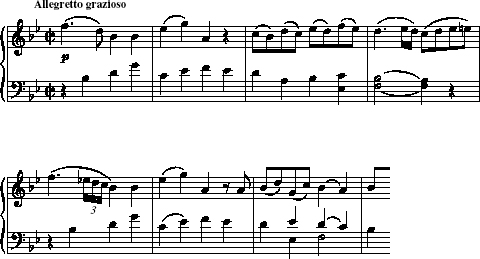

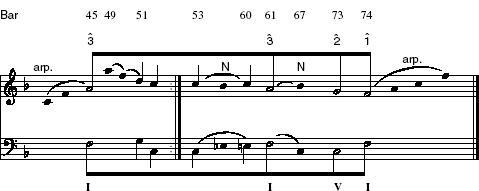

OpenLearn course AA314_1 began by comparing the first eight bars of the last movement of Mozart's Sonata K333 (Example 1) with a pastiche of this style which was musically similar, but artistically awful. Already, it was clear that Mozart's beautifully balanced theme is made up of repeating patterns of notes in an overall downwards shape. This melodic feature – conjunct linear motion in the voice leading – became more prominent in the analysis of these bars in OpenLearn course AA314_2. Examples 2 and 3 reproduce two of the analytical graphs of the first four bars of this theme from OpenLearn courses AA314_1 and AA314_2 respectively.

Activity 1

Look again at the analyses of bars 1–4 of Mozart's theme (Examples 2 and 3). How do these two analyses show features of the foreground and middleground of the music respectively?

Answer

Discussion

Example 2 shows musical processes at the foreground of the music, because it shows the sequence of consonant harmonies in the score. It omits dissonant notes such as neighbour notes, but preserves the outline of all the ‘vertical’ harmonies between the top line and the bass. This is shown as a simple rhythmic reduction.

Example 3 shows some middleground features of these bars, because it shows that some consonant harmonies are subordinate to others. For instance, the second consonant chord of Example 2, the G minor harmony in bar 1, with B♭as the upper note and G in the bass, is shown to be subordinate to the preceding B♭major harmony. In other words, the B♭ chord is prolonged throughout bar 1, subordinating the G minor harmony. The analytical notation represents this hierarchical observation by giving a stem to the B♭ in the bass, but keeping the G as an unstemmed notehead, and indicating that these notes are related to each other with a slur. This process of prolonging one harmony per bar continues throughout the extract.

Other middleground features of the harmony shown in Example 3 are unfoldings in the top line of bars 1 and 2, and a voice exchange in bar 3. These indicate that the melody derives from a two-part structure at this level.

If you are unsure of the meaning of any of the symbols used in Example 3, or of any of the terms used in the discussion above, check them again in the text of OpenLearn courses AA314_1 and AA314_2, or in the Glossary at the end of this free course.

Now look at the final analysis of this section extending the analysis to bar 8.

Activity 2

Look again at the final analysis of Mozart's theme (Example 4 below). Write down answers to the following questions.

-

What additional feature of the music is analysed in this graph, compared to the previous one (Example 3)?

-

What notes in the top and bottom lines would you keep in a graph of the next, deeper, level of the harmony?

Answer

Discussion

-

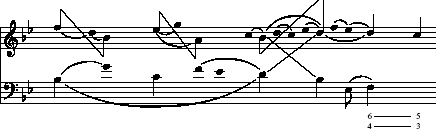

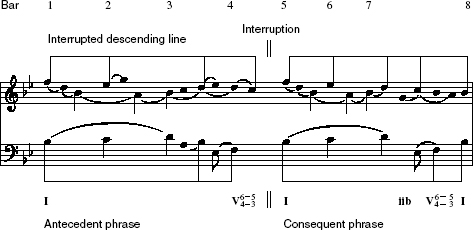

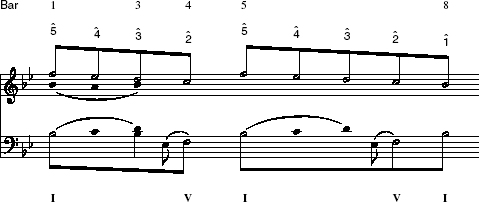

The additional feature of the harmony shown in this graph is the striking linear descent in the melody from the opening F down to the final B♭. This feature controls the harmonic movement of the whole eight-bar phrase, making it a complete course, and a miniature example of interrupted form.

-

In addition to the notes of this linear descent, I hope that you decided that the most important feature of the harmony in the whole section is that it ends where it began, resting on the tonic chord. In other words, the most important notes in the harmony are the initial tonic chord established at bar 11, and the final tonic chord, reached at bar 81 and approached via the dominant chord of bar 72−4 (which is decorated by a subordinate chord and a 6/4–5/3 suspension).

This example looks forward a little to the sort of analysis that you are going to perform with Beethoven's Eighth Symphony. The complete eight-bar phrase derives its beauty and elegance from the simple and logical structure that underlies the exquisite foreground harmony. This structure makes up the form of the section, and can be called the ‘background’ of the harmony.

In order to analyse the form of sections of movements much longer than these eight bars (or the form of whole movements), a few new analytical notation symbols are needed, to distinguish the deepest level of the harmony from the other levels. These symbols can be used to convert the graph of Example 4 to that in Example 5.

Activity 3

Compare Example 5 with Example 4. What alterations have been made regarding the notes included in the graph? What new analytical symbols have been introduced?

Answer

Discussion

In Example 5, the unfoldings and voice exchange are aligned vertically, to show how the melody is based on two independent harmonic voices. This means that the unstemmed notes which unfold each interval have now been omitted.

The new elements of analytical notation are as follows.

-

The linear descent from F down to the final B♭, and the bass movement from tonic to dominant and back to tonic, are each shown using unfilled stemmed noteheads (which look like minims).

-

This overall structure is shown by adding beams to connect these stems (the beams in Example 4 connect filled stemmed noteheads in this way).

-

The notes of the interrupted descending line have been numbered, according to their degree of the scale. These numbers are identified with carets (which look like circumflex accents:

).

).

Example 5 shows just the same analysis of structure as Example 4; but the new notation will be very useful later, when we look at graphs of much longer spans of music: ultimately, whole movements are based on the same harmonic structures as short musical phrases.

This section has revised the concepts of foreground and middleground, and the notation that goes with them, in order to emphasise again how tonal harmony works hierarchically, and can be reduced to simpler and simpler underlying shapes. Whenever you are writing or reading an analytical graph, keep firmly in mind the fact that the symbols we use do not have the same meaning as they do in a score. A hierarchy based on rhythmic notation in a score is used to show harmonic importance in an analytical graph. So unfilled noteheads (which look like minims) identify the harmonically most important notes, filled noteheads (which look like crotchets) the next most important, and unstemmed noteheads show the notes which are inessential to the level of harmony that the graph is analysing.

1.2 Form in Beethoven's symphonic writing

Now let's look at an example from Beethoven's Eighth Symphony. We will start our analysis of the work with the shortest self-contained formal section, which is the trio from the Minuet and Trio that make up the third movement. The minuet occupies bars 1–44 of the movement, and the trio bars 45–78.

Activity 4

Listen twice to Beethoven's Eighth Symphony, third movement, bars 45–78. First, follow the music in the full score attached below. Then listen to it again whilst following the piano score (also attached below). Place a cross in the piano score underneath the first main tonic chord, and underneath the dominant and tonic chords that make up the final main cadence (remember that this movement is in F major). What similarities can you find between the opening and the close of the section?

Click to listen to the extract from Beethoven's Eighth Symphony, third movement, bars 45–78. (2 minutes)

Click to open the full score of Beethoven's Eighth Symphony, third movement.

Click to open the piano score.

Answer

Discussion

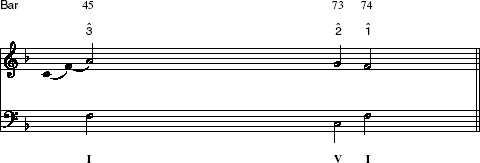

You should have placed a cross underneath the F major chord in the first bar (bar 45), beneath the C major chord in bar 73, and the F major chord in bar 74 (which is prolonged to the end of the section). You probably noticed that the accompaniment in the lower strings is almost identical at the beginning and end of the section (and indeed this texture is maintained throughout), and you may have noted the three-note motive, C–D–E, which acts as an upbeat to bar 45 and to bars 72 and 74 (it is in the horn line; it is also found in bars 73 and 75, but turned upside down).

The task is to analyse how the music is structured between these opening and closing gestures, which look so similar on paper and yet have such different effects in performance. This analytical method is presented on video.

Activity 5

Watch the video clips below.

Click to view first video, part 1.

The first part of the video has built up a preliminary graph of the trio (Example 6). You should now add to this graph by printing it out using the link below the example, following the instructions below.

-

Identify two or three moments in the trio which you think are structurally important; in other words, moments which cannot be missed out of an analysis of the form of the section.

-

Indicate these moments by adding a note to the top line of the graph. Select the note which you think is most prominent, structurally, in the music at that point.

-

Add the note (or notes, if the harmony changes) in the bass which you think will indicate the harmonisation of these notes in the top line.

-

Identify these moments by putting the bar number over each note you have added.

Click to open graph (Example 6).

You may wish to listen through to the trio a couple of times before you do this activity.

Click to listen to the extract from Beethoven's Eighth Symphony, third movement, bars 45-78. (2 minutes)

Activity 6

When you have enlarged the graph in Example 6, watch the video below and follow my discussion of this activity.

Click to view first video, part 2.

The above video clips build up a complete background graph of the trio. This shows the fundamental structure, and some additional detail.

Example 7 gives the final graph of the trio.

1.3 The different elements of a background graph

Now I am going to introduce some technical terms which describe different components of the background graph. The new terms introduced in Example 5 become more important when we analyse a more complicated piece of music, and they will enable you to follow the discussions below of other sections of Beethoven's Eighth Symphony.

The techniques of voice-leading analysis were first developed in German-speaking scholarship. One result is that technical terms exist in both German and English. This course uses the English translations of terms.

As you saw just now, the form of a tonal piece of music is based on one particular note of the tonic triad, which is prolonged (normally through the bulk of the piece) in the top voice of the harmony. This note is called the primary tone (or the head-note). In Example 5, A (the third of the tonic chord F major) is the primary tone.

The primary tone is made to descend, step by step, down to the tonic in order to close the form. This step-wise descending shape is called the fundamental line. The notes of the fundamental line are shown in a graph as unfilled noteheads with stems, and their number in the tonic scale is indicated above them with a caret (in Example 5, as a ![]() descent).

descent).

The fundamental line and the bass voice that harmonises it together make a piece of simple two-part counterpoint. The second-to-last note of the fundamental line is always harmonised by the dominant in the bass (so that in a ![]() descent such as Example 5, the bass always moves tonic-dominant-tonic). The two-part counterpoint which underpins the form of the music is called the fundamental structure.

descent such as Example 5, the bass always moves tonic-dominant-tonic). The two-part counterpoint which underpins the form of the music is called the fundamental structure.

In a voice-leading analysis of form, the background graph can be divided into several phases. At first, the music establishes the primary tone of the form. Sometimes, the primary tone is the first note of the piece; but often, the top voice of the music moves up to it gradually. This initial part of the graph is called the initial ascent.

Then, the primary tone remains the point of reference for the middle part of the graph (which is often the bulk of the piece) until it descends to the tonic note. We call this central part of the graph the prolongation of the primary tone, followed by the structural descent. The descent of the fundamental line to the tonic note is often a short, decisive move, though it may be more spread out; but the final move from 2 to 1 is termed the structural cadence or structural close of the form.

Sometimes, the cadence that completes the fundamental structure is the final cadence of the piece; but often (especially in longer pieces) the final tonic degree is prolonged for some time. We can call this last section the structural coda, and it serves to establish the finality of the close of the piece. It is not, of course, the same as the ‘coda’ in a traditional account of form: it may be the same section of music, but it may be much longer or shorter.

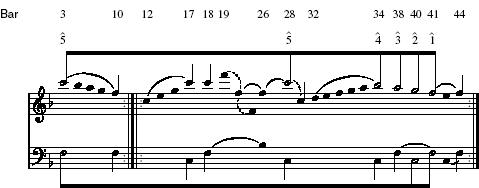

You can see that Example 7, although it describes only a short section of music, contains all the elements identified above. A short initial ascent is followed by a prolongation of the primary tone which covers most of the section, with the last two notes of the fundamental line coming close together in bars 73 and 74, and a brief structural coda, with hunting-horn type arpeggios on the horns and clarinets, emphasises the tonic F major triad at the end.

This trio is structured around a ![]() descent in the fundamental line, as we have seen. In other pieces, however, the fundamental structure can be organised around a descent from either of the other two notes of the tonic chord, as a

descent in the fundamental line, as we have seen. In other pieces, however, the fundamental structure can be organised around a descent from either of the other two notes of the tonic chord, as a ![]() or even an

or even an ![]() structure. In these cases, the structural cadence still takes place at the end of the fundamental line, elaborating the

structure. In these cases, the structural cadence still takes place at the end of the fundamental line, elaborating the ![]() descent. The three possible forms of the fundamental structure are shown as Example 8.

descent. The three possible forms of the fundamental structure are shown as Example 8.

There are two important points which are worth bearing in mind at the conclusion of this initial look at background structure.

First, whilst almost any piece of tonal music can be reduced to one of these three fundamental structures, the point of doing this can only be to show how the composer connects this very abstract background structure with the detail at the foreground that makes the piece sound unique. This means that the real value of an analysis of this sort lies in the elements of the graph or graphs which fill in the details of how the fundamental structure holds the piece together. So in Example 5, the harmonic detail that is extra to that contained in Example 8a, strictly speaking the middleground detail, is what begins to explore Beethoven's approach to the form of this short section. On its own, after all, Example 8a could refer to any of thousands of different pieces.

Secondly, the analysis involved in drawing a background graph is rather different from that involved in drawing a foreground graph. At the foreground, there really is very little room for doubt about what is right and what is wrong. Which notes are consonant and which are dissonant, and the difference between main and subsidiary harmonies, are things which only rarely turn out to be ambiguous (even if they can be difficult to track down). This is less true at middleground levels, as you found out in the discussion of three different ways of analysing the structure of the opening theme of Mozart's Sonata in A major K331 (Examples 28, 29 and 30 in OpenLearn course AA314_2). At the background, even very experienced musicians may have quite different opinions about where the structural cadence of a piece occurs, and which musical events are structurally the most important. But this does not mean that such analysis is pointless. On the contrary, comparing different analyses of the same piece often reveals subtleties and depths to a composer's way of writing music.

With these points in mind, it is now time to look at other parts of Beethoven's Eighth Symphony. We won't be building up background graphs in the sort of detail that we applied to the trio of the third movement. But you should by now be able to follow a background graph alongside listening to the music or reading the score, and understand the description of the form that the graph represents.

2 Analysing the form of the Minuet and Trio

I now want to expand the graph of the trio section of the Minuet and Trio by looking at the form of the whole movement.

Activity 7

Listen twice to the whole of the Minuet and Trio (by clicking the player below), the first time with the full score and the second time with the piano score.

Click to open the full score of Beethoven's Eighth Symphony, third movement.

Click to open the piano score.

Click to listen to the extract (5 minutes).

Print out the piano score and at the minuet section, mark the following:

-

the most prominent note of the tonic triad in the melody line at the opening of the section;

-

the secondary keys to which the music modulates;

-

the most decisive cadence at the end of the section.

Answer

Discussion

-

Since the minuet begins with an arpeggio in the melody line through the whole tonic triad (bars 1–3), you might have chosen any of the three possibilities as the primary tone! But the A and the C seem the most likely, since the A arrives at the note at the top of the first tonic chord (bars 1–2), and the C is the note that begins the melody proper in bar 3. In fact, it is the C which is most prominent melodically, as the melody winds down from C in bar 3 to C an octave lower in bar 6, and then from the high C in bar 7 down to the tonic F at the double bar line in bar 10.

-

After the double bar, there are two modulations, first to C major (bars 11–16) and then B♭major (bars 17–26) before the return to F major from bar 27 onwards. There is a memorable harmonic progression through both C major and B♭major at bars 32–5.

-

The most decisive cadence is harder to identify; from bar 36, there is a constant alternation between dominant and tonic chords. You may have picked either the first cadence (bar 36), or the last one (bar 44), or the point where the horns stop emphasising the cadences in bars 40–1. Clearly we need to look at these bars in more detail.

In order to take account of the features you have just been thinking about, we need to develop a view of how the whole movement fits together. My view of this is again presented using video.

Activity 8

Watch the video below which builds up a complete background graph of the minuet section of the Minuet and Trio. Because the minuet is almost twice as long as the trio, this is not done in quite such painstaking, step-by-step detail as in the last video. Instead, I shall ask you to look at my analysis of the section, and see what you think of it when it is compared with the music.

Click to view second video, part 1.

Click to view second video, part 2.

Activity 9

Listen to the minuet again and follow the analysis in my final graph from the video band you have just watched (Example 9below).

Answer

Discussion

You should by now understand the sorts of decisions I made in order to analyse the form of this movement. Whether or not you agree with my decisions (which are my musical opinion), I hope you can see how I have tried to explain the sense of coherence and logic that Beethoven's music gives me when I listen.

3 Analysing the form of the first movement

3.1 Points to understand

You are now ready to follow an analysis of a much longer and more complex piece of music. We don't have space in a single course to look in any detail at the actual procedure of analysing the harmony of the whole of the rest of the Eighth Symphony, so I will discuss the analysis of only one other movement, the first movement. Here I will present you with my own completed analysis, rather than lead you through the steps that went towards creating it.

Activity 10

Listen again to the first movement of the Eighth Symphony. Follow it in thescore. Then make notes on the following questions.

Click to open the full score of Beethoven's Eighth Symphony, third movement.

Click to listen to the extract, Beethoven's Eighth Symphony, first movement. (8 minutes)

-

Which points seem harmonically most puzzling in terms of their place in the form? Try to identify three or four specific points that need to be explained by any analysis of the movement.

-

Which note of the tonic chord is most prominent early in the movement (in other words, which note would you choose as the primary tone)?

-

Where is the decisive closure of the tonic key (in other words, where would you place the structural cadence of the movement)?

Answer

Discussion

-

You have already done a lot of work with this piece of music, and your list of points will reflect what you view as particularly important. My list of particular moments which an analysis of the form of the movement has to take into account is as follows.

-

The entry of the second subject, which appears to be in the ‘wrong’ key, D major (bar 37).

-

The beginning of the recapitulation. The start of this section can be placed at bar 190 or at bar 198. The former has impressive texture and dynamics, but the latter has more conclusive harmony.

-

The transposition of the second subject in the recapitulation, where it is presented first in B♭(bar 234) and then in F major (bar 242).

-

The place of the coda (bars 301 onwards) in the form of the movement. This more than anything else will affect your answer as to where the main structural cadence is located. The recapitulation ends with an emphatic cadence in the tonic and repeated octave Fs (bars 293–301), but the coda still follows a fair amount of chromatic modulation before the final cadence.

-

-

It is difficult to avoid choosing C, the fifth of the scale, as the most prominent note of the tonic triad in the melody, and therefore the primary tone. Two moments which encourage this are the opening of the melodic line in the very first bar, and the thunderously repeated Cs at the end of the exposition (bars 100–104).

-

There are several places towards the end of the movement where Beethoven re-establishes F major with great insistence. Perhaps you chose the end of the recapitulation, where, after dominant and tonic chords are repeated several times to establish the cadence, the tonic chord thunders out fortissimo in arpeggios through almost three octaves in the violins (bars 293–7). This would make the structural coda of the voice leading coincide with the coda section of the sonata form. Or again, perhaps you chose the moment where the tonic reasserts itself (again fortissimo) for the last full statement of the first subject in the coda (bars 323ff.). Or perhaps you chose the final cadence in bars 358–64, where the tonic chord arrives with self-effacing quietness to close the movement. All three passages have competing claims to be the point of true closure of the form, and clearly this is something that requires a deeper analysis.

This is anything but an exhaustive list even of the interesting features to do with form in this movement. I have left out lots of wonderful aspects of Beethoven's harmony which do still feature in my analytical graph; the above list is more a selection of some moments that simply cannot be avoided whatever the method of analysis. Now it is time, though, to consider my thoughts about the movement in the light of all the work you have already done with it.

Activity 11

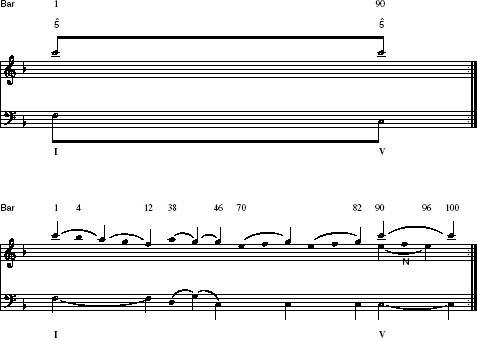

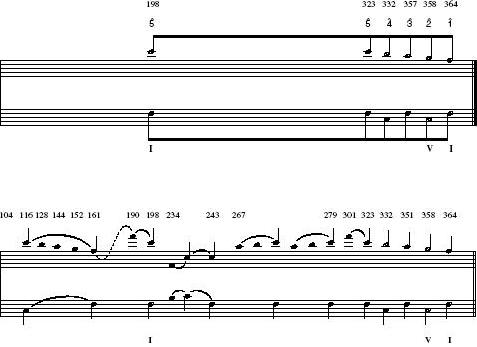

First, look at my analytical graph of the movement (Example 10). I have arranged it on two levels for greater clarity, so that Example 10a presents only the fundamental structure of the movement, whereas Example 10b, aligned underneath it,gives a little more detail, still at the background level.

Compare Example 10 with the score (at link below), using the bar numbers to identify the events in the music represented by each point of my background reduction.

Click to open the full score of Beethoven's Eighth Symphony, third movement.

Then, try listening through to the movement again, but this time follow the music with the graph rather than the score.

What does the graph claim about the way Beethoven has structured the movement? Refer especially to the moments listed in the discussion of the previous activity. Do you find this analysis convincing?

Click to listen to the extract Beethoven's Eighth Symphony, first movement. (8 minutes)

Answer

Discussion

First, I'll summarise what the graph indicates about the four passages identified in the first question of Activity 10.

-

The harmonic importance of the second subject in the exposition is analysed as its eventual establishment of the dominant, C major, at bar 46. The apparently ‘wrong’ key of D major (bar 37) is seen as part of the approach to C major, since at a background level it moves to a G major harmony which is the dominant of the dominant (this happens in bars 44–5).

-

I have analysed the harmonic importance at the beginning of the recapitulation as being located in bar 198. This is shown in both Example 10a and Example 10b, because this is a crucial moment in the voice leading of the movement, where the prolonged tonic harmony supporting the

of the fundamental line is re-established.

of the fundamental line is re-established.

-

The transposition of the second subject in the recapitulation (bars 234–43) is analysed in Example 10bsimilarly to the appearance of this theme in the exposition, so that the key of B♭is seen as part of the progression to the tonic, F major. The way that Beethoven handles the transposition here emphasises the C in the top voice, which is part of the prolongation of the fundamental structure.

-

The coda's principal function in the movement in terms of voice leading is analysed in both Example 10a and 10b as being the descent of the fundamental line. This means that the beginning of the coda proper (bar 301) is analysed, at this very deep level, as merely a subsidiary stage of the prolongation of the primary tone, C, in the top voice. This is a good example of a place where an event that is very striking at first hearing (the top F in bars 297–301) is of lesser importance to the structure of the whole movement, in my view, than one might at first think. Even after the recapitulation closes, the C is still to be resolved (glance at bar 323 in the score to see its prominence), and this happens over quite a long section from bar 332 to bar 364. The coda is therefore seen as the decisive closure of the form of the movement.

Let's look at this analysis in a little more detail. The structure of the development sectionis summarised here as another descent from C down to F, and a lengthy register transfer of this F up an octave between bar 161 and bar 190. The way that a descent from C to F repeatedly forms the unifying structure of a whole section at a very deep level makes it what we might call a ‘structural motive’ in the work.

Another issue which should be considered is where the recapitulation begins.

Using the voice-leading graph it is possible to see that the thematic recapitulation and the harmonic recapitulation happen out of synchronisation with each other. This is similar to the way that when the second subject enters, both in the exposition and the recapitulation, it is before the harmony has reached its destination key. In other words, this deliberate lack of synchronisation between theme and tonality is a structural feature shared by the return of the first subject and the entry of the second subject – what we could call another sort of structural motive. Indeed, this ‘correction’ of the key of the second subject is very typical of Beethoven – as opposed to Schubert, who often avoids the dominant key for the whole of the second subject area in an exposition.

Before we consider the fundamental structure analysed in Example 10, notice that I have been deliberately inconsistent regarding the amount and level of middleground detail I have included in Example 10b. At some points I have included quite local features (such as the harmonic movement in bars 37–46 and 234–43); at others I have taken a much broader sweep of music (as with the descent in bars 116–60); other sections I have more or less omitted altogether (such as the marvellous harmonic detail in bars 160–90). This is always the case with a graph of the background structure of a long and complex piece of music. I have included details which I think are particularly relevant to my personal interpretation of Beethoven's formal thinking, and another analyst might have chosen other details to emphasise. Whilst this analysis is personal, it is not arbitrary. The analysis always aims to interpret and explain the notes in Beethoven's score. Now let's see what other insights into the form can be obtained from this attempt to analyse a fundamental structure.

3.2 The fundamental structure and the form

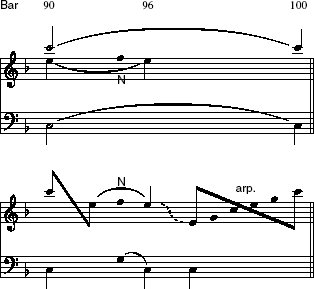

Although Example 10a contains no more than the notes of the fundamental structure with an indication of the bar numbers where I think they occur, it nevertheless identifies some important aspects of the form. The whole of the exposition is seen as a journey from tonic to dominant, with the C maintained as the focus of interest in the melodic lines throughout. Let's look for a moment at the end of the exposition. The structural C is established in bar 90: in the score you can see this note arrive in the violin and flute parts, after a long prolongation of the dominant chord in bars 83–9. The last section of the exposition, from bar 90 onwards, focuses in its melodic line first on E, alternating with its neighbour note F, with alternating C major and G major seventh chords; until this E climbs through the arpeggio in bars 96 to 100 to reach the C again.

Activity 12

Example 11 above shows an analysis on two levels of the bars just discussed (90–103). Compare Example 11 with the score, and listen to these bars whilst following the graphs. How do these graphs analyse the structure of this final section of the exposition?

Click to open the full score of Beethoven's Eighth Symphony, third movement.

Click to listen to the extract Beethoven's Eighth Symphony, first movement, bars 90-103. (20 seconds)

Answer

Discussion

I have analysed these bars as a prolongation of the tonic harmony, with C at the top, and with the intervals from C to E and back again unfolded. The alternation of C major and G major triads is therefore an ‘alto-voice’ feature at this background level – these chords are not true perfect cadences here, but a reinforcement of the C major dominant harmony established at bar 90. Example 11a shows the background as it is given in Example 10b, and Example 11b shows the middleground elaboration of this structure.

Let's return now to Example 10a, and look further at what its picture of the fundamental structure means. The graph analyses the whole of the development section as leading up, harmonically speaking, to the re-establishment of the tonic F major at bar 198. This is done through a few modulations to keys not terribly distant from F major, aiming towards the long dominant pedal from bar 176 onwards; even the D flat chords around bar 168 are part of a middleground feature in the bass which forms a neighbour note to the C dominant pedal. When the tonic harmony arrives to inaugurate the recapitulation at bar 198, the ![]() of the fundamental line is re-introduced at the top of the melody. In my graph, the whole recapitulation is then analysed as keeping the

of the fundamental line is re-introduced at the top of the melody. In my graph, the whole recapitulation is then analysed as keeping the ![]() unresolved.

unresolved.

To consider what my analysis means here, look at the end of the recapitulation section, bars 280 to 300, which are parallel to the bars in the exposition that you have just listened to. You can see that this is almost a note-for-note repeat, in fact, transposed from C major to F major. My analysis claims that, despite the very emphatic arrival of the F and the tonic harmony from bar 287 onwards, there is no sense of completion for the movement as a whole here, because there has been no prominent and decisive fall from ![]() to

to ![]() in the upper voice. So we are not surprised at bar 301 when the repeated Fs continue in the bassoons, because we are still waiting for this closure.

in the upper voice. So we are not surprised at bar 301 when the repeated Fs continue in the bassoons, because we are still waiting for this closure.

Activity 13

See if you agree with the way I hear this section (bars 280–300) by listening to it again now. This time just listen, without following the score.

Click to listen to the extract Beethoven's Eighth Symphony, first movement, bars 280-300. (30 seconds)

Answer

Discussion

It is rather unfair to ask you whether you agree that something has not been heard in these bars! It is the sense of ‘unfinished business’, rather than restfulness, in the continuation of the music into the coda at bars 301 ff. which leads me to feel that we still need a structural descent to give the whole movement a satisfying closure.

The structural descent, when it occurs, seems very prominent to me. The first subject reappears ff at bar 323, where the C is emphasised in the violins, doubled by clarinets and bassoons. The melody then comes to rest in bar 332 on B♭, harmonised by a C major chord, where there is even a pause marked. This prominence of B♭has been a feature throughout the movement, and here it acquires great weight aurally. Straight away in bar 333, we hear the B♭leading to an A in the violins, as we would expect; this is no more than a passing foreground feature, though, and an exhilarating passage builds up from here, with the melody slowly rising from bar 341 until the tonic harmony is reached again at bar 351. I have based my analysis on two features of the harmony at this bar: first, there is no dominant chord in bar 350 (despite the C in the bass in the last beat), so this cannot be the final cadence of the movement even though it is the loudest arrival of the tonic anywhere at fff and secondly, although the violin line rises right up to a C at the end of bar 350, the tonic arpeggios at bars 351–3 give great prominence to A, the first note in the violin line. I have therefore analysed the whole of bars 333–51 as a prolongation of the descent B♭–A in the top voice. This makes the dominant chord at bar 354 (repeated in bar 358) the structural dominant for the whole movement. So the G at the top of the violin parts in these bars is the second-to-last note of the fundamental line, and the final note arrives at bars 364–5, alternately played as the top note in strings then woodwind. The fact that this F is approached by the leading note in bars 362–3 is typical of the close of a long movement, and does two things: it emphasises that the tonic is ready to be reached, because the structural descent has already happened, and it serves to spread out the notes of this descent evenly, making the whole section balanced and satisfying (the notes come in bars 323, 332, 351, 354/8 and 364).

Activity 14

Re-read my commentary above, and then listen to the movement's coda (bars 323-end) whilst following the relevant section of Example 10. Can you hear the notes of the structural descent, as I have analysed it, where they each occur?

Click to listen to the extract Beethoven's Eighth Symphony, first movement, bars 323–end. (1 minute)

Answer

Discussion

Although it requires very long-range listening to hear this descent spread out over more than forty bars, I hope that the selected bar numbers marked (and the CD track numbers, if you were able to see them on your player) in Example 10 helped you to follow my analysis. I think that it is this deep structure that accounts for why this final section of the movement sounds so satisfying.

Whilst this is not the only way to analyse large musical structures, there are some aspects of Beethoven's craft – such as his mastery in creating a sense of achievement and fulfilment at the conclusion of a movement – which are often noted by listeners, but which seem to escape most attempts at analysis. If you have found this section of the course at all convincing, you should feel that we have at least approached one answer to the question of how Beethoven accomplishes his artistic effect.

3.3 What is the point to voice-leading analysis of form?

This analytical discussion may have seemed very dry, and it is quite difficult to follow, simply because this is a long and complex piece of music. But the aim behind it is far from dry, nor is it an attempt to plaster a pre-existing model of how music works on to the score come what may. The voice-leading graph in Example 10 becomes meaningful only when it is compared in detail with the score. You may have noted some of the unusual aspects of the movement, especially where it differs from many other examples of sonata form. Here, these features (such as the beginning of the second subject and recapitulation sections) are seen to fit into a much more standard progress between tonic and dominant key areas, and comparing the harmonic analysis in this course with a thematic analysisshould have deepened your appreciation – and respect – for Beethoven's complete mastery of his craft in every detail from the smallest to the largest. My voice-leading graph does not try simply to reduce Beethoven's harmony to a trivial counterpoint exercise, as if that were all that it consists of; rather, it shows how the unusual aspects of the harmony are held in balance by a coherent background form, so that the tension between these perspectives produces the excitement and exhilaration which we feel ever more deeply the better we come to know the music.

There is one further advantage to a voice-leading approach in analysing form, and that is the scope that it gives for identifying large-scale features which recur within the movement – even the whole work – which serve to bind together its different parts as a single course. I have already identified two of these structural motives: the non-synchronisation of thematic and harmonic formal boundaries, and the many small ![]() descents in the movement. This gives a special importance to the note B♭. In the opening bars of the movement, the melodic line centres on B♭in bars 4–6 as part of a descent from the initial C to F, a descent completed (with another prominent B♭) in bars 9–12. B♭then recurs at several points in the movement as part of a prominent, long-range descending line, with different harmonic settings. In bars 20–32 it is repeated again and again in the violin line, before being harmonised as a neighbour note to the A in bar 34 onwards, so that the B♭is used to introduce the ‘wrong’ key of D major for the second subject. And we have just looked at the memorable pause on the B♭in bar 332 which inaugurates the close of the whole movement. If you think back for a moment to our earlier analysis of the Minuet and Trio, you will remember that there, too, there was an emphatic and memorable stopping-point on the B♭which formed part of that movement's structural descent: look again at bars 34–5 of the minuet to see the similarity. In this way, the voice leading of the different movements reveals features which bind together the whole work.

descents in the movement. This gives a special importance to the note B♭. In the opening bars of the movement, the melodic line centres on B♭in bars 4–6 as part of a descent from the initial C to F, a descent completed (with another prominent B♭) in bars 9–12. B♭then recurs at several points in the movement as part of a prominent, long-range descending line, with different harmonic settings. In bars 20–32 it is repeated again and again in the violin line, before being harmonised as a neighbour note to the A in bar 34 onwards, so that the B♭is used to introduce the ‘wrong’ key of D major for the second subject. And we have just looked at the memorable pause on the B♭in bar 332 which inaugurates the close of the whole movement. If you think back for a moment to our earlier analysis of the Minuet and Trio, you will remember that there, too, there was an emphatic and memorable stopping-point on the B♭which formed part of that movement's structural descent: look again at bars 34–5 of the minuet to see the similarity. In this way, the voice leading of the different movements reveals features which bind together the whole work.

I hope that you have enjoyed this rather intensive look at the sonata form of this first movement. To close this course, I am going to discuss one more topic, and that is how background voice-leading structure relates to the shape of sonata form as we normally describe it.

4 Voice-leading analysis and sonata form

Sonata form can be divided into sections in several different ways. One of these is to describe it as an expanded version of the binary form of the baroque (Figure 1), emphasising the contrast of key areas within the first half.

Another scheme is to label the sections as a three-part or, sometimes, a four-part sectional form, emphasising the contrast of thematic material. This sort of description was more common in nineteenth-century textbooks, and indeed is better suited to sonata-form movements from the nineteenth century.

Either way of describing sonata form can be applied to the first movement of Beethoven's Eighth Symphony.

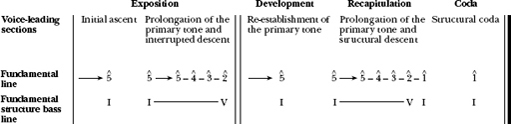

How, then, does this picture of sonata form relate to the fundamental structure of a voice-leading analysis? Are there features of a graph such as the ones we have been looking at which will always map on to sonata form in the same way? It is tempting to assume that there should be. Let's start by looking at how the graph of Beethoven's first movement (Example 10a) might compare with Figures 1 and 2. I have put all three of these together in Figure 3, and added some of the labels for the fundamental structure which we discussed earlier.

Activity 15

Look carefully at Figure 3. What does it say about the relationship between sonata form and voice-leading structure?

Answer

Discussion

Figure 3 points out several things about the connections between the voice-leading analysis and other ways of describing sonata form.

-

The divisions between sections (exposition, development, and so on) do correspond to important features in the graph.

-

The form works around structural movement in the bass from I to V to I again. This may involve an actual modulation to the dominant (as in the exposition), or it may not (as in the recapitulation).

-

the fact that sonata form is (in one respect) a two-part structure, involving a break (and normally a repeat) at the end of the exposition, means that the fundamental structure of the graph has also to be divided into two, rather like the interruptions we looked at in OpenLearn course AA314_2.

There are some features of Figure 3, however, which suggest that this cannot be the way that voice-leading works in every sonata-form movement. For one thing, thinking of the description of the fundamental structure at the beginning of this course, there is no place for an initial ascent here (the primary tone is the first note of the symphony), and no structural coda either, since the final tonic chord is simply repeated after bar 364. For another thing, the prolongation of ![]() in a

in a ![]() fundamental line could not carry on over the break in the form at the end of the exposition in a major key, because the

fundamental line could not carry on over the break in the form at the end of the exposition in a major key, because the ![]() cannot be harmonised by the dominant chord. And for a third thing, sonata form movements in a minor key, as you know, frequently end the exposition in the relative major and not the dominant, and so in these cases, the bass movement would have to be different.

cannot be harmonised by the dominant chord. And for a third thing, sonata form movements in a minor key, as you know, frequently end the exposition in the relative major and not the dominant, and so in these cases, the bass movement would have to be different.

For these reasons, we need to be aware that there are innumerable different ways in which a voice-leading background graph might fit within a sonata-form movement. And indeed, analysis of many different works shows that different ways of handling the harmonic structure of a sonata-form movement make the principle means by which composers achieve the tremendous variety of approaches to this form that we know from the thousands of different movements that share sonata form. As with Beethoven's Eighth Symphony, significant divisions of the sonata-form scheme nearly always correspond with harmonically important moments. But the exact disposition varies a lot.

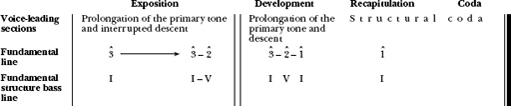

Let's look at a few examples. Figure 4 shows a typical way in which the voice leading of a sonata-form movement may work.

Figure 4

This is a very common scheme, and is perhaps the most obvious way of identifying the background of two of the three major-key first movements from Mozart's piano sonatas which you studied in OpenLearn courses AA314_1 and AA314_2 (K309 and K333). In both cases, the ![]() of the interrupted descent in the exposition corresponds to the beginning of the second subject. The third work whose first movement we looked at in detail there, K545, is also very similar in design. In this movement, though, the recapitulation has a most unusual beginning, where the first subject returns in the subdominant key (F major). At a background level, this forms part of the structural descent, so that the

of the interrupted descent in the exposition corresponds to the beginning of the second subject. The third work whose first movement we looked at in detail there, K545, is also very similar in design. In this movement, though, the recapitulation has a most unusual beginning, where the first subject returns in the subdominant key (F major). At a background level, this forms part of the structural descent, so that the ![]() of the fundamental line (F) appears at this point.

of the fundamental line (F) appears at this point.

One feature of Figure 4 which deserves comment is the way that the fundamental structure is split into two, so that the movement to the dominant at the end of the exposition corresponds to a move to ![]() in the fundamental line. The term for this sort of structure is ‘interrupted form’, since the structure is interrupted at the double bar, and so repeated in the second part of the movement. You saw some smaller examples of interruption at the end of OpenLearn course AA314_2, including the first eight bars of the rondo from K333 with which we opened this course (Example 4). As a background feature, it is frequently used on this very large scale as part of the patterning of an entire sonata-form movement.

in the fundamental line. The term for this sort of structure is ‘interrupted form’, since the structure is interrupted at the double bar, and so repeated in the second part of the movement. You saw some smaller examples of interruption at the end of OpenLearn course AA314_2, including the first eight bars of the rondo from K333 with which we opened this course (Example 4). As a background feature, it is frequently used on this very large scale as part of the patterning of an entire sonata-form movement.

Here is another possible way in which voice leading and formal sections may coincide. Let's imagine a descent from ![]() to

to ![]() this time.

this time.

Figure 5

Activity 16

Consider the three examples of background voice-leading schemes and sonata form (Figures 3, 4 and 5). What do the differences between these schemes imply about different ways of balancing the component parts of a sonata-form movement?

Answer

Discussion

The main difference between Figures 3, 4 and 5 is the weight given to the development, recapitulation and coda. In Figure 3, it is the coda that gives the balancing closure to the harmonic structure of the movement. The coda is obviously very important, and is quite substantial in length (73 bars out of 373, or 20 per cent of the movement) as is typical of Beethoven. In Figure 4, on the other hand, more weight is given to the end of the recapitulation, where the repeat of the second subject in the tonic key leads to the completion of the motion of the harmonic structure. The coda may still be an important section, but its harmonic function is slightly different. Finally, Figure 5 shows a scheme where the development section is much more important to the structure, and where it closes with a dominant chord (normally a dominant pedal) which has such weight within the form that it decisively moves it on, so that the return of the first subject at the opening of the recapitulation completes the harmonic journey of the movement.

Whilst this is, admittedly, rather an unlikely scheme for a sonata-form movement, there is a famous analysis by Schenker himself of the Finale of Beethoven's ‘Eroica’ symphony (although this particular movement follows a rather different formal plan) in which the decisive structural cadence is placed similarly early on, at bar 277 of a 473-bar movement.

Finally, let's look at one more scheme, which describes a typical minor-key movement.

Figure 6

This outline is different from that in Figures 4 and 5 in that it does not show an interrupted form, but shows instead how the modulation to the relative major (degree III of the scale) can still support a prolongation of ![]() (or

(or ![]() ) in the top voice of the background level of the form. It also shows the importance that the dominant degree, which often forms a pedal at the end of the development section, may have. Although there may not be a modulation to the dominant key area in the whole movement, the dominant degree will still be crucial to the way that the form is constructed.

) in the top voice of the background level of the form. It also shows the importance that the dominant degree, which often forms a pedal at the end of the development section, may have. Although there may not be a modulation to the dominant key area in the whole movement, the dominant degree will still be crucial to the way that the form is constructed.

These four examples, although abstract, indicate some of the huge variety of ways in which composers make the harmonic outline of sonata form work. There are countless other ways in which a voice-leading fundamental structure may correspond to the categories of sonata form. The thing to bear in mind, when you read an analysis of this kind (as of any sort), is that form in music is not a rigid set of procedures that happen the same way in every piece. Although the fundamental structure at the background of the voice leading is a very simple piece of counterpoint, and is indeed shared between almost all tonal pieces, the whole point of an analysis is to show how this simple background structure gives coherence and meaning to the complex and intriguing design at the foreground of the music. Such an investigation should only deepen our appreciation and respect for an expert such as Beethoven.

5 Conclusion

This course completes your introduction to the systematic analysis of voice leading in pieces of tonal music. You have encountered a large number of new technical words and ideas in this course. The following terms are the principal ones that have been discussed.

-

foreground, middleground and background

-

fundamental structure

-

fundamental line

-

primary tone

-

initial ascent, prolongation of the primary tone, structural descent, structural coda

-

structural cadence

-

interrupted form

This course does not expect you to be able to analyse a whole movement's background structure yourself from scratch. However, you should now understand the sorts of musical observation that go into making such an analysis, and be able to read an analytical graph in relation to the score of the music, and discuss the musical thoughts that it embodies.

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Course image: Ilmicrofono Oggiono in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Licence.

All video extracts are taken from AA314 Studies in Music 1750–2000: Intrepretation and Analysis. Produced by the BBC on behalf of the Open University © 2001 The Open University.

The full score for Beethoven's Eighth Symphony is taken from: Beethoven, L, Symphonies, no. 8, op. 93, F major, edited by Max Unger, foreword by Wilhelm Altmann, available online from the William and Gayle Cook Music Library, Indiana University School of Music at www.dlib.indiana.edu/ variations/ scores/ baj2627/ [accessed 24 April 2008].

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University