Art in Renaissance Venice

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 25 April 2024, 6:41 PM

Art in Renaissance Venice

Introduction

Trade took Venetian merchants all over the Mediterranean and as far as China, a fact that affected not only the city’s economic prosperity but its cultural identity, making fifteenth-century Venice one of the most culturally diverse cities in Europe, a fact clearly depicted in many Venetian paintings. This course reviews some aspects of the social and cultural diversity of fifteenth-century Venice and how they affected the city’s art. In particular it focuses on Venice’s relations with the East and its several manifestations, the legacy of Orthodox Christian Byzantium, and the contemporary Islamic societies of the Ottomans and Mamluks. Studying Venice and its art thus offers a challenge to the conventional notion of Renaissance art as an entirely European phenomenon.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of level 3 study in Art History.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

be aware of the art and culture of fifteenth-century Venice

be aware of the nature of cultural exchange in Renaissance Europe

understand how Venetian art challenges the canonical view of Renaissance art as a purely western European phenomenon

start to develop skills in critical visual analysis based on the study of selected images of Renaissance art

understand the geographical, political and commercial forces that set Venice at the centre of a broad network of trade and power relations and the complex ways these were reflected in Venetian art and architecture.

Renaissance Art Reconsidered

This course explores the relationship between Venetian art and the art of both Byzantium and other geographical areas to the East. Venice looked eastward as the result of its unique position as a maritime trading centre facing not only inwards, towards the Italian peninsula, but also outwards, towards Asia and the Middle East. All this was in addition to Venice’s trade and cultural exchange with northern Europe. These are two of the ‘axes’ of intersection with other cultures noted in the chapter. The third axis is a chronological rather than a geographical one: that of Venice’s relations with the past of antiquity. As you will learn, this was a very different one from other Italian cities, which had been part of the Roman Empire, and therefore bore architectural and sculptural reminders of the classical past.

A great deal of the course is devoted to the representation of ‘the East’, a term that is problematised both in the chapter Introduction and in the chapter itself. It is very important for you to be aware of the distinctions made in the chapter, because such a broad term cannot be properly understood in a simple generic sense. Whenever you come across this term, make sure you understand in what sense it is being used, especially if you encounter it in older literature, where it may be used quite differently.

At the beginning of the course, Paul Wood presents the concept of ‘the collage, the montage or … the palimpsest’ as a metaphor for Venetian culture during this period, and emphasises the diversity of peoples who co-inhabited the islands of the lagoon.

Foreword

Trade in spices and sugar took Venetian merchants all over the Mediterranean and as far as China.1 Alum, an important chemical in the dying of fabrics, and therefore an important ingredient in the cloth industry on which so many urban centres relied, was imported from Muslim territories and, with sugar, was by far the largest import to the European mainland until the 1460s, when it was discovered in the Papal States at Tolfa. By the fifteenth century the Venetians had established an efficient merchant navy of state-owned galleys, which made regular journeys in convoy throughout the Mediterranean, the Baltic and to Flanders and England. By the 1440s the state convoys left Venice twice a year to Syria and once a year to Tunis, Barbary, the Black Sea, the south of France, Spain, Beirut and Alexandria. Only one of these convoys left the Mediterranean for Flanders and England. In addition, a few pilgrim galleys also went from Venice to the Holy Land every year. The number of sailings does not seem high by modern standards but the size of the Venetian craft and their organisation in convoys meant that they were relatively secure against pirates and other perils. A disadvantage was that the large number of people they had to carry meant that they had to put into port regularly to pick up supplies, another important role for their colonies such as Crete, ideally placed en route for the eastern shores of the Mediterranean.

Venice’s trading partners affected not only the city’s economic prosperity but also its cultural identity, making it, as Paul Wood explains in this chapter, one of the most culturally diverse cities in Europe, a fact clearly depicted in many of its paintings. Cardinal Bessarion, who was from Trebizond on the Black Sea and called himself a ‘Greek’, wrote in the document giving his library to the city of Venice that

no place is more suitable, or more appropriate for my fellow countrymen in particular. The peoples of almost the whole world come together in great numbers in your city, but especially the Greeks, whose first port of call as they sail from their own lands is Venice. They have besides a familiar relationship with you; when they put ashore at your city it seems that they are entering another Byzantium. 2

But as this course shows, the use of the term ‘the East’ to describe all cultures east of western Europe can be misleading, simply because it carries with it connotations of the ‘exotic other’ and ignores the fact that Byzantine/Orthodox Christian culture was very different from that of Islamic/Muslim culture.

In this course written by Paul Wood, the influence of the unique cultures of Orthodox Christians, Ottoman Turks and the Mamluk kingdom on Venetian art are discussed in turn. Non-Christian culture was nevertheless kept at arms-length. While Orthodox art demonstrably had fundamental effects on Venetian painting as it was influenced by the intense spirituality of Byzantine and post-Byzantine icons, contact with the Ottoman and Mamluk territories resulted in the more superficial appropriation of motifs, costumes or even the exotic animals the Venetian merchants, diplomats and artists saw on their travels and which are common features of Venetian art.

Carol M. Richardson

1 Art in fifteenth-century Venice: ‘an aesthetic of diversity’

A distinctive place

The Venice Biennale is the longest-running of the major international exhibitions that have come to play such an important part in the contemporary practice of art. Inaugurated as long ago as 1895, the Biennale is organised on national lines. For the fiftieth exhibition in 2003, under the overall rubric of ‘Dreams and conflicts’, the United States pavilion showed work by the African-American artist Fred Wilson. Wilson’s display consisted of a collection of objects and installations addressing the multicultural, multiethnic makeup of Venice itself, from the Renaissance to the twentieth century. The installations included an opulent Murano glass chandelier, in black glass, numerous figures of the ‘blackamoor’ types used to advertise Venetian consumer products from the seventeenth century to the present day and images of Renaissance paintings depicting non-European figures. In the Biennale catalogue the point is made clear: ‘As the world of today struggles again with issues of immigration, ethnicity and race, the topic of diversity in historical Venice is particularly resonant.’ 1

Much of the interest in looking at the Renaissance at the beginning of the twenty-first century lies in this sense of ‘looking again’. At a point when the boundaries of the western canon are coming under greater scrutiny than at any time in its history, it follows that the vaunted ‘rebirth’ of that tradition is itself going to be a suggestive site of encounter for received meanings and interpretations. In historical representation, consciously or otherwise, the horizon of the present is always drawn around the continent of the past. Arguably, a period gets the Renaissance it deserves – or needs. For its early historian Jacob Burckhardt, writing in 1860, the impetus to research the Renaissance was a conviction of its status as ‘a civilisation which is the mother of our own’. 2 Contemporary historians, by contrast, are inclined to explore differences between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and our own times. 3 Not only is the map of the societies and cultures that produced Renaissance art substantially redrawn, but our sense of what counts as ‘art’ itself is subject to redescription. In a way that echoes the decentring of painting and sculpture from the contemporary practice of the arts (exemplified by, among others, Wilson’s Venice installation), our sense of Renaissance cultural practice is now moving to re-embed painting and sculpture in a matrix of ritual and building, mechanical reproduction, design and consumption, from which the modern system of the arts detached it. 4 The hierarchical distinctions of the canon have come to seem out of tune with our own cultural hybridity in an epoch of globalisation. That said, no one could sensibly argue with claims for the relevance of an understanding of Renaissance art to the subsequent western tradition. 5 What stands at issue are the terms of that understanding. As new historical enquiry begins to shed light on the diversity of Renaissance experience, the consequences for a sense of western individual identity, as historically grounded in the Renaissance, are considerable. 6

Recurring figures in recent studies of Venetian culture are the collage, the montage or, in another variant, the palimpsest. In all these cases, however, the intention is clear: the figure is meant to bring out the layering of Venetian culture, of Venice as a place of marked juxtapositions. 7 Neither is this a wholly retrospective construct. At the end of the fifteenth century, the French ambassador Philippe de Commynes remarked that ‘most of the people are foreigners’. And this perception of a society in which northerners (Flemish and Germans), Dalmatians, Greeks, Muslims, Jews and mainland Italians mingled with indigenous Venetians was sharpened in the sixteenth century by the Venetian writer Francesco Sansovino: ‘Peoples from the most distant parts of the world gather here to trade and conduct business’, people who ‘differ among themselves in appearance, in customs and in languages’. 8 This characteristic is frequently attributed to Venice’s particular geographical and historical situation: a series of offshore islands in the far north-east of Italy, at the head of the Adriatic, which conferred on Venice a distinctive relation to some of the core values associated with the Renaissance. When one thinks of the term ‘Renaissance’, its governing sense is of a rebirth of the art, architecture, literature, science and philosophy of antiquity. Alone among major Italian cities, Venice had no antiquity. There are no significant classical ruins or inscriptions in the Venetian lagoon. The city having been the creation of refugees during the period of the barbarian invasions in the fifth century, after the collapse of the Roman Empire, the Venetian Renaissance of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries had to import its sense of antiquity. This happens both in the form of a delayed response to the innovations of the Tuscan Renaissance, spreading out through centres like Padua in the 1440s, and later as Venice expanded into mainland Italian territories towards the end of the century, in the form of a predominantly literary interest in Roman pastoral. 9 However, the negative impact of this historical absence on Venetian Renaissance culture was balanced by a positive factor. Venice’s geographical location made it the single most important trading centre between Western Europe and the East. It is thus the nature of Venice’s relations along three ‘axes’ – with the past of antiquity, with northern Europe, and particularly with the East – that produces the diversity so remarkable to contemporaries and historians alike.

In Renaissance studies, the concept of the ‘East’ has conventionally been taken to refer to the territories of the Eastern Orthodox Church, that is to the Byzantine Empire centred on Constantinople (as distinct from the legacy of the Western empire, the domain of the Catholic Church centred on Rome).10 More recently, following wider contemporary usage, the ‘East’ has been understood to refer to a complex of Asian societies stretching from Turkey to China, with a particular emphasis on Islam. 11 In the present chapter, I discuss the influence on selected examples of the art of fifteenth-century Venice of three ‘Eastern’ cultures: Christian Byzantium, the Islamic society of the Ottoman Turks and that of the Mamluks, who at that time ruled the territories of present-day Egypt and Syria.12

For several hundred years, particularly from the beginning of the thirteenth to the end of the fifteenth centuries, Venice was a maritime power. Its naval dockyard, the Arsenal, was the biggest industrial complex in late medieval Europe. This was a time before Columbus’s voyages to America, before the Portuguese opened a sea route to Asia, when the eastern Mediterranean remained one of the most active centres of world economic and cultural development. Venice more than anywhere else was the gateway through which the manufactured goods of Europe spread out to the East and a vast range of stuff from the East – spices and carpets, metalwork and perfumes, colours, shapes and ideas – entered the European consciousness. 13 Because of this, fifteenth-century Venice even looked different. With its power based on the stato da mar (the ‘empire of the sea’), the city was literally built on the water. The palaces of the wealthy merchants that stood aside the Grand Canal and other waterways were highly distinctive. For most of the fifteenth century the dominant elements were a characteristic admixture of the Gothic and the Islamic. Architecture remains largely beyond the scope of this course, but it is nonetheless worth pausing to note the appearance of these buildings. The façade of the Ca’ d’Oro (Figure 2), begun in 1421, presents a diverse collection of Gothic arches and tracery, topped by Islamic-inspired cresting along the roofline. The pointed ‘ogee’ arch is itself a hybrid. Found in English Gothic, though less usual in continental Europe, it also occurs in Asian architecture. Deborah Howard has argued that ‘the intention behind the introduction of the ogee arch and its adoption as a trademark by the Venetian merchant class was to allude to a mental image of the Orient’14 – a ‘mental image’ composed out of myriad individual memories of trade in the East, characteristic Islamic forms in mosques and markets, ornaments and furniture, descriptions in travellers’ tales, even the doublecurves found in the hulls of the galleys themselves. By the later fifteenth century, the palace of the diplomat Giovanni Dario does adopt features of a more typical ‘Renaissance’ façade, drawing on developments elsewhere in mainland Italy (Figure 3). But even here, the classical columns and the rounded arches are mixed in with expensive imported coloured marbles, and set in circular mounts which may have been observed by Dario on diplomatic missions to the Mamluk court in Cairo.

This layered architectural heritage is to be seen most vividly on the two great buildings which stand adjacent to each other on the Piazza San Marco, the central ceremonial space of Venice (Figure 4). The basilica of San Marco and the Palazzo Ducale marry Gothic tracery and arches with, respectively, Byzantine domes and mosaics, and coloured tiles in an Islamic lozenge pattern. Traces of centuries of interaction with the East abound throughout the city, forming a marked contrast to the rational composition of the façades of the classically influenced renovatio movement which emerged in the early sixteenth century. 15 The specific character of Venice as a physical space is thus inscribed by the sedimented experience of cultural otherness, manifest in both form and colour: ogee arches, gothic pinnacles, asymmetrical façades, overhanging balconies, narrow twisting streets, coloured marble and painted plaster. 16

Apart from the physical, built environment of the city, something else contributes to making Venice different: the organisation of Venetian society. Renaissance Venice was a corporate society, long thought to be structurally hierarchical. At the top were the patricians, the nobile, amounting to no more than about 4–5 per cent of the total population, with a legally enshrined monopoly on political power. From them a Doge was elected, almost always a senior figure. He was head of state for life but was prevented from accumulating wealth and power on the model of, say, the Medici in Florence. Below the patricians was a larger, but still numerically small, layer of citizens, the cittadini, comprising approximately 5–8 per cent of the population. And below them was the vast majority, almost 90 per cent, of the popolani (the people). These distinctions have now been shown to be more fluid than was once thought. 17 Nevertheless, in an age of great social upheaval and almost continuous wars, the city-state, according to its own officially sanctioned ‘Myth of Venice’, remained stable and survived for 1,000 years, from the end of the Roman Empire to Napoleon.

Underlying this stability was economic power. Controlling a trading empire based in the eastern Mediterranean, but stretching into northern Europe and Asia, Venice enjoyed great wealth. This wealth encouraged innovation as well as cultural diversity, and information was no less important to the accumulation of wealth than the trade in spices and exotic goods. In the late fifteenth century, Venice became a centre for the new technology of printing. The area of the visual arts was broadened by the publication of prints by artists from both Italy and the north, the German master Albrecht Dürer prominent among them. Venetian printers were also engaged in map-making, not least nautical maps of the main sea-routes and ports around which Venetian trade was organised. And it has been established that ‘in the course of the fifteenth century more books were printed in Venice than in any other city in Europe’. 18 The diversity which marked contemporary Venetian life was mirrored in the printing industry, which produced considerable numbers of Ancient Greek texts, books of Jewish history and translations of Arabic works. Peter Burke notes that Venice was ‘a centre of printed information about the East linked to travels of merchants and others’, concluding that the ‘information structure was related to, if not a simple expression of, the economic, social and political system’. 19 Within the overall framework of prosperity, the secret of continuing stability can be found in critical points of flexibility within the hierarchy. Of particular significance for the arts is the fact that, despite political power as such being reserved for the hereditary patrician class, the citizens played an extremely powerful role as a kind of permanent civil service. Among the institutions for which they were responsible were the scuole: lay – albeit deeply religious – confraternities, in the larger cases extremely wealthy, which were responsible for a wide range of activities approximating to what we would think of as social services. There were five of the important scuole grandi, and some hundreds of smaller scuole piccole of varying size and influence. Several of these were linked either to trades (including the painters), or to foreign groups in the city. The largest such group consisted of merchants from Germany, and it was to their Fondaco dei Tedeschi that Dürer was attached during his two stays in Venice in 1494–5, and a decade later in 1505–7. 20 As well as providing many commissions for artists, the scuole played an important role in maintaining the social cohesion which, allied to naval supremacy, underwrote Venetian power and prosperity.

Dürer’s time in Venice seems to have been a mixture of frustration and excitement, crowned eventually in triumph. The excitement derived from the variegated life he encountered there, exotic sights and a social whirl in which men of ‘noble sentiment and honest virtue’ mingled with ‘false, lying thievish rascals’. 21 In his final letter before leaving he tells of spending 100 ducats on colours he was able to buy there, and also of managing to purchase two expensive oriental carpets for his friend and patron, the Nuremburg humanist Willibald Pirckheimer. The downside consisted of falling foul of the protectionist Venetian guild system. As a German visitor resident in the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, Dürer provoked jealousy among Venetian artists, even to the extent of being warned to take precautions against being poisoned. Indeed, he was summoned three times before the Venetian magistrates and fined, in effect for illegal trading by practising as an artist while not being a member of the scuola dei pittori. The ups and downs turned to triumph, however, with the reception of the major painting he produced in Venice, during 1506, for the church of the German fondaco, the Madonna of the Rose Garlands, now in Prague. The picture is large, though by no means enormous at just under two metres wide. Its effect does not depend on its size, but on the extraordinary synthesis of Venetian and northern elements that it embodies. Dürer’s technical mastery of Venetian colour and perspective is combined with a vivid northern naturalism that extends from the grasses in the foreground, through dozens of individuated figures set against framing trees, to a distant city and, beyond that, high mountains. Dürer’s achievement was to render an entirely artificial, symmetrically arranged, symbolic scene of the Virgin surrounded by flying angels, bestowing garlands on the pope and the Holy Roman Emperor as both spatially and colouristically unified and even credibly naturalistic. Its success was sealed when no lesser figures than the doge and the Patriarch, the head of the church in Venice, visited him to see it. As Dürer wrote, it ‘stopped the mouths of all the painters who used to say that I was good at engraving but, as to painting, I did not know how to handle my colours’. 22 The status of the individual may have been different in corporate Venice from what it was in other Renaissance Italian city-states, notably Florence. But its richness and diversity, and the high cultural level those factors brought in their train, led Dürer, the artist, to reflect as he prepared to leave Venice for Germany in late 1506, ‘How I shall freeze after this sun! Here I am a gentleman, at home only a parasite.’ 23

2 Two devotional paintings

In his correspondence of 1506 with Pirckheimer, Dürer had singled out for special mention among the Venetian artists that he had encountered the senior figure of Giovanni Bellini. Giovanni appreciated Dürer’s skill, publicly praised him and even asked to buy a picture from him. In turn, Dürer included a quotation from Giovanni’s San Giobbe altarpiece of c.1480 in his Madonna of the Rose Garlands, in the shape of the lute-playing angel in the centre foreground. Dürer commented to Pirckheimer that, in his judgement, though of advancing years, Giovanni was ‘still the best painter of them all’. 24 Giovanni Bellini, born before 1440 and generally regarded by art historians as the foremost fifteenth-century Venetian painter, was a member of a family of artists: a workshop headed by his father Jacopo (c.1400–70/1), and including his elder brother Gentile. 25 In this section I shall consider two devotional paintings by Giovanni Bellini – the Madonna Greca of c.1470 and the San Giobbe altarpiece as a way of bringing into focus certain broader features of art in Venice. It is a standard claim within the discourse of Renaissance art history that Venetian art is distinctive. The contrast most frequently drawn is with Florence, and it focuses on the particular range of effects associated with Venetian painting, especially the relative priority accorded to colour over form and design, and a resulting appeal to the senses rather than the mind. Emotionally expressive effects produced by colour and painterly brushwork are identified as the key characteristics of Venetian Renaissance art. Fully evident in the sixteenth-century work of figures such as Titian and Tintoretto, these features emerge in the late fifteenth century with Giovanni Bellini. The reasons are partly technical (to do with the use of oil paint), partly historical (to do with the dual legacy of Venice’s relations with its eastern trading partners and with the northern Gothic tradition) and partly geographical (to do with Venice’s location).

It is claimed of Venice’s location, for example, that the misty quality of the Venetian atmosphere is not conducive to an interest in sharply defined forms, or that the constant flickering of light on water makes for a fascination with the more evanescent effects of painting, an interest in the painting as an affective surface rather than as a window onto some depicted scene. These questions of sensibility are largely unresolvable, but certain aspects of Venetian art are undeniably attributable to the environment. One of the central forms of Italian Renaissance art is the public mural decoration, painted in fresco on plaster, But Venice is built in the sea; in its damp climate, fresco does not survive. However, it was the city’s maritime situation that meant Venetian art was open to cultural influences from the East – and one of the most important of these influences came from Byzantium. Two of the central categories of Byzantine art, both of which bear on the Bellini pictures, are mosaics and icons. 26

From its earliest days until the twelfth century, Venice had stood at the western limit of the Eastern Christian Empire, centred on Byzantium. 27 The first permanent Venetian trading post was established in Byzantium in 1082, though commercial links had existed long before that. However, as the Byzantine Empire declined and that of Venice expanded, the balance of power and influence gradually changed, until crisis point was reached in 1204. In that year the Venetian Doge succeeded in diverting the Fourth Crusade from its destination in the Holy Land to Constantinople. After a siege, the city was ruthlessly sacked. As a consequence, huge amounts of booty made their way to Venice, ranging from jewels, metalwork, and both bronze and marble sculptures to porphyry columns and sheets of marble for use in the decoration of buildings.

The basilica of San Marco is the single most important transmitter of Byzantine influence into Venetian culture. It was first established in the ninth century to house the relics of Venice’s patron saint, Saint Mark, which were transferred to the city from Alexandria in 829. Both in its external architectural form and its interior, San Marco is distinct from the conventions of Italian and northern churches alike, with their characteristic decorative schemes either of fresco or stained glass. San Marco began to assume its present form in the late eleventh century, based directly on the plan of the church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, that is, a Greek cross with five domes marking each arm and the central crossing point. Thereafter, it was in a continuous process of expansion and embellishment until the fifteenth century and beyond. Mosaic decoration had started in the late eleventh or early twelfth centuries, but a surge of work followed in the wake of the capture of Constantinople. In addition to the four life-size bronze horses of classical antiquity, shipped over and set above the main entrance, the domes, arches and vaults of the interior were decorated with mosaics by artists called from Constantinople, often working with glass tesserae actually brought back for the purpose (Figure 5). The effect is to suffuse the dimly lit interior with an atmospheric golden glow, as if the biblical scenes occupy a different realm elevated above the mundane world of the human spectator. Mosaics depict episodes from both the Old and New Testaments, including many related to Egypt, where Saint Mark preached. Outside, more mosaics above the portals told the story of the transportation of the saint’s relics from Alexandria to Venice (today, only one remains). A further important example of the spoils from Constantinople, and the single most venerated image in the church, is the tenth-century icon of the Madonna Nikopoia, the ‘bringer of victory’ (Figure 6). This image of the Virgin and Child in the hodegetria pose was not only displayed on the high altar on important feast days but was also used as a talisman to ward off the enemies of Venice during times of crisis, just as it had previously been used in Byzantium. 28 In addition to the pictorial mosaics and the icon, Byzantine effects were present throughout San Marco in the many columns in marble and porphyry, as well as sheets of coloured, patterned marble, stripped from Constantinople and used to decorate the walls and the elaborately patterned floor.

Constantinople was retaken by the Greeks from Venetian domination after less than 60 years, and a new dynasty secured: the Palaiologans. By the time of Bellini’s paintings, however, two centuries later, not just Italy but the whole of Christendom was convulsed by news of the final collapse of the Byzantine Empire. Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks, under the leadership of Mehmet II, in 1453. Despite calls for a new crusade to repel the infidel, there was in fact no collective response. One of the immediate effects for Venice, however, was an increase in the numbers of the Greek community there, as Christian refugees fled from Muslim expansion. The result of the influx of scholars, coupled with a rapid expansion of the printing industry, was that in the second half of the fifteenth century Venice became the main centre of Greek learning in the West.

For the Florentine Giorgio Vasari, writing in the sixteenth century, his sense of a ‘rebirth’ of the arts was defined explicitly against ‘the ancient manner … of these Greeks’. First Cimabue and then Giotto ‘banished completely that rude Greek manner’ – that is, with ‘the outlines that wholly enclosed the figures, and those staring eyes, and the feet stretched on tiptoe, and the pointed hands, with the absence of shadow and the other monstrous qualities of those Greeks’. The grip of illusionism has been powerful in the post-medieval western tradition. Influenced by contemporary humanism and its commitment to a truthful description of nature, Vasari seems never to have entertained the idea that there was a reason for the exaggerated eyes and the outlines of Byzantine art. The sense that a complex and evolved history informs Byzantine painting, concerning the role of art in relation to the overarching dictates of the Greek Orthodox Church, is swamped by a creative misreading which regards its formal characteristics simply as failed verisimilitude. For Vasari, the achievement of the Florentine Renaissance consisted precisely in the fact that ‘the Greek manner … was wholly extinguished’. 29

In Venice, however, the situation was less clear-cut. Giovanni Bellini’s half-length Madonnas, painted for private devotion, are a constant of his long career, stretching from c.1460 to the second decade of the sixteenth century. As a form, they are consciously archaic, evoking the spirituality of Byzantine models – none more so than the Madonna Greca (Figure 7). The darkness of the colouring and the sobriety of the forms coupled with the overall stasis of the composition are immediately suggestive of the icon – an effect heightened in this case by the Greek lettering naming the Mother of God. An important compositional device reinforces the mood suggested by the facial expressions of mother and child. In many early Renaissance paintings, the Virgin is positioned in front of a rich cloth of honour, often suspended on cords. Here, the red cords are merely suggested, and the cloth falls in a dark monochrome – so dark, in fact, that a spatial ambiguity is set up. Instead of a dark plane set against a deep spatial volume (for example of sky), the black rectangle can be read as a void, an effect heightened if the Greek letters are seen as being inscribed on a flat surface (for example, a frame around a window). Taken together, the subdued colours, the Virgin’s sad, withdrawn expression and the dark ground, be it plane or space, contribute to an overall mood of reflective melancholy. The purpose of these half-length Madonnas is to inspire solitary meditation, lifting it out of a particular time and place, devoid of secular or narrative distractions. The Madonna Greca perhaps retains something of the Byzantine hodegetria pose, the Child being not so much the subject of a maternal embrace as seeming to be presented to the viewer. The aim is to bring to mind an anticipation of Christ’s eventual sacrifice. The image of the Child is meant to evoke pietàs, in which the dead Christ is supported by the Virgin and saints. Rona Goffen writes: ‘Bellini’s conception is essentially iconic: simple, emotionally restrained, psychologically distant.’ Most important, she concludes, ‘the austerity of mood, as of image, associates his works with the Byzantine tradition’, in effect rendering them ‘the Western equivalent of the icons of the East’. 30

Early fifteenth-century Venetian painting had been defined by a mix of Byzantine and the International Gothic style: an art that, although distinct from the Byzantine, was nonetheless an art of surface rather than depth, of linearity, and of emphatic, even luxurious, decorative effects. Gothic began to enter Venetian art in the fourteenth century through the church-building programme associated with the religious orders of the Franciscans and Dominicans. It offered a new dynamism, a contemporary inflection on the more static and timeless values of the prevailing Byzantinism that seems to have chimed with the vigorous mercantile capitalism that was beginning to emerge.

Jacobello del Fiore’s depiction of an allegorical figure of Venice as Justice, painted for the civil penal court of the Palazzo Ducale in 1421, is a case in point (Figure 8). The two flanking figures of the Archangels Michael and Gabriel are simply not intended to be spatially or volumetrically credible representations of the human body in action, as the dual Tuscan revolution of humanism and perspective was beginning to demand. Jacobello’s picture space is barely defined – a blue void in which the figure of the Virgin/Venice/Justice, with her sword and scales, perches on a throne flanked by two lions, the whole ensemble having a rather ‘tilted’ effect on a low plinth. The central space of Justice’s throne has only the most rudimentary relationship to the scenes depicted on either side, with Michael arching balletically above a writhing dragon, a somewhat plumper Gabriel hovering to the right, coherence established only by a common low horizon line. In both ‘wings’, the values of surface effect and vividness take precedence over spatial verisimilitude. The great twist of Michael’s figure in particular enlivens the left-hand panel, echoing the sinuous curls of the scroll. His extravagant armour is further embellished with golden embossing; a red and green cloak is tied nonchalantly around his neck, as Justice is dispensed. Invisible in illustration, the gold parts of the picture are raised in relief, or in the case of the tripartite arch placed over the painted image, to establish a lateral, linear animation to the composition as a whole. Although the sophisticated tension of these Gothic effects in the work of artists such as Jacobello and his eminent contemporary Gentile da Fabriano (who spent time in Venice around 1410 contributing decorations to the Doge’s Palace) needs to be distinguished from the hieratic immobility of the Byzantine, the art historian Peter Humfrey points out that such Gothic richness struck a chord with the Venetians, ‘whose aesthetic tastes would have been formed by their experience of the gilded splendour of San Marco, and also of travel to the Levant’. 31

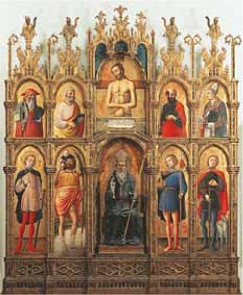

The family workshop was the organisational basis of Venetian art, and in the fifteenth century, the main rival to the Bellini was the Vivarini studio, comprising Antonio, his brother Bartolomeo, his brother-in-law Giovanni d’Alemagna and his son Alvise. However, whereas the Bellini seem to have been open to the new approaches concerning the representation of space and volume coming from Tuscany, a more ambiguous response characterises the Vivarini. Towards the end of the century, Alvise developed an interest in spatial coherence and solid form, but overall the Vivarini workshop continued to embody a traditional Gothic-influenced approach for much longer (Figure 9); in the case of Bartolomeo this persisted until his death in the 1490s. The polyptych format, the lack of concern with coherent spatial illusion, and the copious use of gold on both the Gothic frame and the backgrounds to the figures would all have contributed to the highly traditional effect of such painting – something which in all probability points not merely to relatively conservative attitudes on the part of the artists, but to a continuing taste for the older established forms on the part of their patrons and audiences in the Veneto.

This Gothic-Byzantine use of gold was one of the key signifiers against which the Tuscan Renaissance was defined. 32 No less a figure than Leon Battista Alberti writes in the 1430s: ‘There are some who use much gold in their istoria. They think it gives majesty. I do not praise it.’ He goes on to make the point that even in the case of a subject involving copious amounts of gold – in his example, Dido of Carthage – the artist should renounce its use, ‘for there is more admiration and praise for the painter who imitates the rays of gold with colours’. 33 As Michael Baxandall pointed out, Florentine quattrocento art shifted the criterion of artistic value from ‘the value of precious material on the one hand’ to ‘the value of skilful working of materials on the other’. This, moreover, was no small matter, but ‘the centre … the most consistently and prominently recurring motif in everybody’s discussion of painting and sculpture’. 34

Jacopo Bellini seems to have encountered these new ideas in Ferrara, around 1440. In 1438–9 Ferrara was the initial site of the great conference on the unification of the Orthodox and Catholic Churches intended to provide a united front against the inexorable rise of Islam. Alberti was a member of the papal delegation, and manuscript copies of his book came into the possession of humanist intellectuals at the Ferrarese court, where in 1441 Bellini was involved in a competition to paint the portrait of the duke, Lionello d’Este. Most of Jacopo Bellini’s painted oeuvre has been lost. Surviving examples indicate a transitional mix of Gothic elements – a relative flatness of both figures and space, and inconsistencies of scale – combined in the landscape backgrounds with a naturalism derived from northern painting (Figure 10). However, in two large albums of drawings which he made between the 1440s and 1460s, Jacopo experimented more thoroughly than any Venetian contemporary with Florentine perspective, and with the achievement of consistent spatial illusion (Figure 11). 35 These interests must have permeated the Bellini workshop, and affected the development of his sons Gentile and Giovanni.

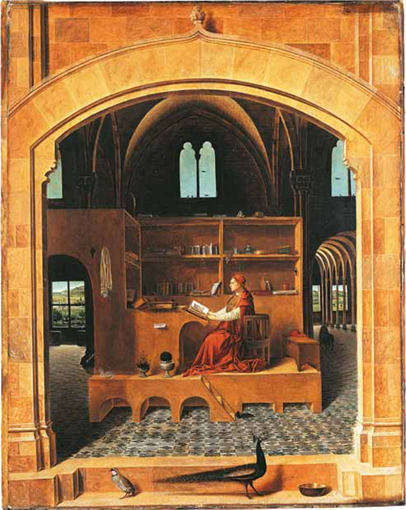

The increasingly naturalistic effects that were being sought were further enhanced by a new medium, oil paint. This underscores a further element in the ‘collage’ of Venetian art, namely influences deriving from northern art. Both Jacopo Bellini’s Virgin and Child with Lionello d’Este of c.1440 and Giovanni’s Madonna Greca of c.1470 were painted in egg tempera. The rather dry effect of this medium was surpassed for effects of depth and luminosity by the oil medium, which had been developed in the north by Jan van Eyck and others from the 1430s onwards. Such paintings quickly had an impact in Venice when they began to arrive in the late fifteenth century as a by-product of increased levels of trade between Venice and the north. 36 Although there is evidence that Giovanni Bellini was experimenting with oil around 1474–5, the most important stimulus to its widespread adoption was the appearance in Venice in 1475–6 of the Sicilian painter Antonello da Messina. Sicily also had trading links with the north, and Antonello had already mastered the Flemish technique of oil painting in works such as Saint Jerome in his Study of c.1474 (Figure 12). It seems to have been the first-hand experience of Antonello’s work that facilitated the full-scale breakthrough into the use of oil paint as an expressive medium that came to characterise Venetian painting from Giovanni Bellini on into the sixteenth century.

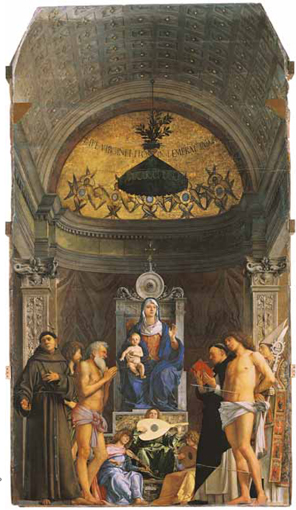

The painted panel of the San Giobbe altarpiece is almost five metres high, and two and a half metres wide (Figure 13). Originally it would have been raised quite high off the ground, above and behind the altar, within an imposing architectural frame. The visual match between the physical pilasters of this setting and the painted ones behind the Virgin and saints enhances the lifelikeness of the scene, as if it is taking place in a space just beyond that occupied by the viewer. Bellini’s use of the oil medium in combination with perspective and anatomy derived from his father (as well as the example of Andrea Mantegna, who had married into the Bellini family while working in nearby Padua in 1453) results in a spatial illusion more comprehensive than anything yet achieved in Venetian art. This illusion, moreover, is of a physical continuity from the mundane to divine, which is quite at odds with Byzantine views. This combination of the Florentine perspectival armature and the Flemish oil medium is the key to the painting’s effects – effects which came to be seen as paradigmatically Venetian. Bellini does not reproduce the sculptural effects (in the sense of static, or ‘carved’) nor the intellectual effects (in the sense of rationally conceived) of Florentine painting of the period. By mastering the oil medium to reproduce the effects of light on different surface textures, Bellini is able to satisfy the traditional Venetian taste for sensuous effects and rich materials without, as in the preceding Gothic style, allowing surface patterning to dominate over a convincing sense of three-dimensional depth.

The single, flexible medium of oil paint produces effects of candlelight on gilded surfaces (as in the almost impressionistic dabs of white and light yellow in the golden half-dome), an illusion of the presentness of flesh, of matt textile and shiny marble. Bellini is using his up-to-date techniques to represent a setting which simultaneously depicts contemporary Renaissance architecture – the pilasters, capitals, architrave and coffered barrel vault – and conveys strong echoes of the antique. The Madonna’s pose is hieratic and Byzantine, while the represented half-dome evokes the basilica of San Marco. In effect heeding Alberti’s admonishment to use painterly skill to reproduce the effects of light on gold, Bellini uses modern oil paint to represent light glinting on the gold tesserae of Byzantine mosaic. Even the flat Byzantine cherubim which surround the mosaic depicting the story of Genesis in the atrium of San Marco are reproduced in Bellini’s coherent evocation of spatial depth. The result is that the archaic is shifted away from its negative connotation in Vasari – where it signifies the static, the old-fashioned, the inept – towards a positive connotation of depth and continuity. The painting is made in Venice, understood as the modern, cosmopolitan, entrepôt for goods and ideas in equal measure; it is made of Venice, conceived as ancient and rooted, in unbroken spiritual continuum with the archetypal Christian city of Constantinople.

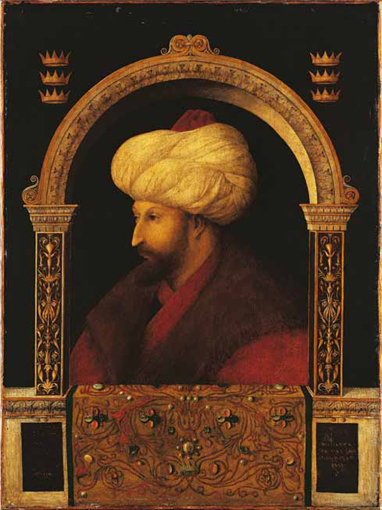

3 A portrait

One of the most intriguing portraits of the Renaissance period is of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II, the conqueror of Constantinople. Painted from life in 1480, its author is the Venetian painter Gentile Bellini (c.1429–1507) (Figure 14). These are curious conjunctions. What was an Italian painter doing in a Turkish court? Why did an Islamic monarch want to have his portrait painted by a western, Christian artist? In a sense, this modest picture figures not just a man, but the relationship between two cultures.

Gentile Bellini was the elder brother of Giovanni, and by the common consent of later generations, the lesser artist. What Gentile lacked in talent, however, he made up for in terms of organisational skill. It was he who took over the family workshop after the death of Jacopo in c.1470, and he who became the most powerful artist in late fifteenth-century Venice. One historian calls him ‘the principal impresario’37: he gained the most important commissions for the decoration of the Grand Council Chamber in the Palazzo Ducale in 1474 as well as others for the scuole grandi, received a knighthood from the Holy Roman Emperor and became the focal point of the diplomatic mission to the Ottoman court that issued in his portrait of Mehmet II. Furthermore, this was not just any court. In the second half of the fifteenth century, after 1453, the Ottomans emerged as not only the one serious imperial rival to Venice in the eastern Mediterranean, but for the next 100 years a real challenge to the hegemony of western Christendom as such.

Mehmet ascended to the Ottoman throne for the second time in 1451, aged 19. 38 His original tenure as an adolescent had been unsuccessful and his father had needed to come out of retirement and reassume power. After his father’s death, Mehmet did not fail for a second time. He immediately began building his military power, and a policy of expansion rapidly led him to the siege of Constantinople. The city was by then almost all that remained of the former Byzantine Empire. The large Ottoman army and navy, estimated at 80–100,000 men, faced a defending force of only about 7,000. Despite the imbalance of forces, the siege lasted 55 days, but on 29 May 1453, a date perceived as one of European history’s turning points, Constantinople fell to the Turks.

News of the fall of Constantinople, which reached Venice a month after it happened, and Rome a week later in July 1453, set off a panic in Christian Europe. Nonetheless, the immediate reaction, to unite in a crusade to retake Constantinople from Islam, foundered on the reefs of internecine squabbling and self-interest on the part of individual states. Before the end of the year, Venice had concluded a treaty which established a permanent embassy in Turkish Constantinople, and secured the continuing domination of Venetian trade in the eastern Mediterranean (something for which collective excommunication by the papacy for betraying Christendom was deemed a fair price to pay). 39 The peace lasted a decade, but was then followed by a draining 15-year war between Venice and the Ottomans which broke out in 1464. This history has a bearing on Bellini’s portrait. By 1478 Venetian wealth and trade had become so adversely affected as a result of the war that peace negotiations were opened. The experienced diplomat Giovanni Dario travelled to Constantinople charged with acceding to as many demands as were necessary to preserve Venetian trade in the region. The terms of the treaty concluded on 25 January 1479 were harsh for Venice, including financial reparations for the costs of the war and the payment of an annual rent for trading within the Ottoman Empire.

On the positive side, the permanent ambassador, or bailo, in Constantinople was re-secured. Mehmet, meanwhile, had built up the city from the impoverished and depopulated shell it had been after the conquest a quarter of a century earlier into a new capital of 60–70,000 inhabitants. A relevant notion to consider at this point is the western image of the barbaric oriental despot. Recent research has shown that, rather than being a constant figure of relations between the Christian West and Islam, this notion crystallised only in the late sixteenth century. 40 For well over 100 years, from the fall of Constantinople until the last quarter of the sixteenth century, fear of the Turks was mixed with admiration for their social system, which seemed to grant them in equal measure irresistible military power and enviable cultural riches. The same Mehmet who was responsible for thousands of executions and was in one report described as ‘feared and dreaded, ruthless and cruel … a second Nero and far worse’41 also reputedly spoke several languages, wrote poetry and possessed considerable knowledge of the literature and philosophy of antiquity. An eye-witness, subsequently quoted in a contemporary Venetian chronicle, reported that before the siege of Constantinople, Mehmet enjoyed daily readings from ‘ancient historians such as Laertius, Herodotus, Livy and Quintus Curtius and from chronicles of the popes and Lombard kings’. 42 Kritovoulos of Imbros, a Greek scholar, recounted how he ‘used to read philosophical works translated into Arabic from Persian and Greek and discuss the subjects which they treated with the scholars of his court’. 43 What matters here is less a question of the objective truth or otherwise of the claim, than of how Mehmet’s identity was being fashioned. At about the same time Vespasiano da Bisticci wrote of Federigo da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, that ‘He was ever careful to keep intellect and virtue to the front, and to learn something new every day’, going on to catalogue his patronage of the arts, architecture and music, as well as his deep knowledge of both classical authors and the scriptures. 44 Half a century later, no less ambiguous a figure than Henry VIII was recorded as frequently receiving Sir Thomas More into his private apartments, ‘and there sometime in matters of astronomy, geometry, divinity, and other such faculties, and sometimes of his worldly affairs, to sit and confer with him’. 45 The point is not, therefore, that Mehmet’s learning (nor indeed Henry VIII’s) was incompatible with brutality, but that Mehmet’s identity was being constructed not as an alien despot, but as a characteristically Renaissance prince. 46

One of Mehmet’s most important projects was the construction of a new palace complex in Constantinople – the Topkapý Palace – from which the Ottoman Empire was administered. Although many Christian churches were taken over and converted into mosques, the Orthodox Church had been re-established, and a degree of multiculturalism with Christians and Jews existed within the overall Islamic culture of the city. Mehmet continued his personal fascination with the West, partly, it would seem, for its intrinsic interest, partly for strategic ends – building up knowledge of contemporary Italy with a view to its eventual incorporation into the Empire. According to the then widespread view of world history as rooted in the Old Testament Book of the prophet Daniel, the four pagan empires of Babylon, Persia, Greece and Rome were to be followed by a fifth empire uniting the world. It was not unusual for Renaissance scholars in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century to worry that with Christendom prey to internecine warfare, this empire would be Islamic. In 1521 a report by the Venetian ambassador stated that the Sultan ‘holds in his hands the keys to all of Christendom’, and as late as 1576, it was still being lamented that ‘the fall of such an empire by the hands of men is therefore the vainest thing to think of’. 47

In discussions with the Venetian delegation during the peace negotiations of 1478–9, Mehmet’s interest in western culture, contemporary as well as classical, seems to have been a topic that arose – including his grasp of the tradition whereby rulers reinforced their power through the circulation of images of themselves on coins and medals. As an experienced Venetian diplomat, Giovanni Dario was, of course, fully conversant with the artistic situation in Venice, and one of the requests that emerged from Constantinople in the summer of 1479 was for a ‘good painter’ to make medals and to paint the Sultan’s portrait. 48 After 1453, Venice had lost a string of important colonies in the eastern Mediterranean, with consequent damage to its overseas trade. For both military and commercial reasons, Venice needed to secure its accommodation with the Turks; complying with Mehmet’s artistic desires – both in terms of palace decoration and the dissemination of his own image – was going to be a useful means to this greater end. One is reminded of Michael Baxandall’s observation that ‘in the fifteenth century, painting was still too important to be left to the painters’. 49 In short, the Venetian government would have done all it could to satisfy Mehmet’s desire to propagate his image. Within a month of receiving the request, a painter was on his way. The leading artist in Venice at the time, in charge both of the decoration of the Grand Council chamber in the Palazzo Ducale and of producing the official portrait of the doge, was Gentile Bellini.

Portraits of the doges were displayed in a frieze above the Venetian history paintings in the council chamber. In keeping with the corporate spirit of Venetian life the point of them was less to celebrate the individual and his achievements than to represent the individual as part of a collective – the head of a family, officer of a scuola or, in the ultimate case, the doge. The most renowned representation of this absorption of individual personality into that of the office-bearer is Giovanni Bellini’s portrait of Doge Leonardo Loredan of 1505, now hanging in the National Gallery in London. But before that, artists were producing more hieratic and austere bust-length images, modelled on antique coins. Gentile’s portrait of Doge Giovanni Mocenigo (Figure 15), completed just before the summons to Constantinople, shows him facing left, in profile, his elevated status conveyed by the flat gold ground, the gold collar and the characteristic horned hat, the cornu, embossed with geometric designs. Following an established formula, only the doge’s face is lightly modelled, conveying just sufficient information for the painting to qualify as a portrait rather than a stereotype. There seems little doubt that Gentile Bellini’s ability to fulfill contemporary requirements for an individuated likeness, combined with a classically legitimated sense of the gravity of office, led to his being chosen for the mission to Constantinople in 1479.

In some ways, the surprising thing about Gentile Bellini’s year and a half long sojourn in the Ottoman capital is what he did not do. Because of his prestige in Venice, Gentile was for long regarded as the father of an ‘Orientalist’ style that emerged in Venetian painting around the turn of the sixteenth century. But in fact he produced no images of Ottoman society, no paintings of contemporary Ottoman architecture or social life to equate with those on which his reputation in Venice rested. He did, however, make several studies of individual Turkish people in daily costume, which formed the basis for many subsequent depictions of Turks and other Orientals in western art (Figure 16). Gentile was the best known, but not the only, western artist involved with the Ottoman court. Slightly earlier another painter, Matteo de’ Pasti, had been arrested as a spy by the Venetians in Cyprus, en route to Constantinople, for having in his possession maps of Italy. More successful was the Venice-born Costanzo da Ferrara, sent by the King of Naples, who was there during the late 1470s, possibly 1478. 50

The principal work of Costanzo’s to have survived is his portrait medal of Mehmet of c.1480 (Figure 17a). This image of a powerful man provides an interesting instance of the way images of Orientals entered art, often built up from a single actual observation. Costanzo’s model was Pisanello’s portrait medallion of the Byzantine Emperor, John VIII Palaiologos, made at the time of the Council of Orthodox and Catholic Churches in 1438–9. 51 The portrait of Mehmet is comparable to Pisanello’s image of the Byzantine Emperor, not least through its use of exotic headgear to signify ‘otherness’. The reverse of the medal shows an equestrian image of the Sultan (Figure 17b). This has its roots in a sheet of drawings by Pisanello, apparently life studies of the Byzantine Emperor’s entourage. They show the emperor standing, clad in a full-length cloak, some details of the cloak’s embroidered hem, and another image of the emperor, mounted on horseback and wearing the characteristic Timurid hat. 52 This observed image, adapted for the circular proportions of Pisanello’s medal, was in turn used as the compositional basis for the equestrian portrait on the reverse of Costanzo’s medal of Mehmet 40 years later.

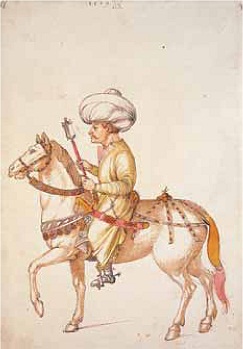

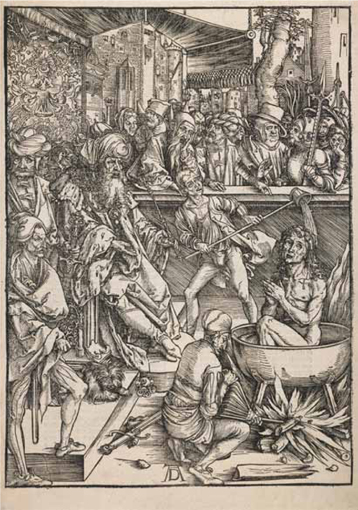

Subsequently, this image became transformed into a generic representation of an ‘Ottoman rider’ by no less a figure than Dürer during his first visit to Venice in 1495 (Figure 18). Rosamond Mack has remarked of this kind of borrowing that ‘artists tended to adapt a small repertory of authentic images to a variety of representational uses’, concluding that what they reveal, despite the level of commercial contacts between East and West, is ‘a limited vision of the Orient’. 53 Dürer seems also to have had access to Gentile Bellini’s studio in 1495 and to have seen work in progress on his monumental painting of a Procession in the Piazza San Marco (see Section 4). Dürer was interested in collecting exotic types for subsequent incorporation into his own pictures, and to this end made a copy of one of Bellini’s preparatory studies of Ottoman figures in the background of the picture, presumably sketched from life during Gentile’s earlier sojourn in Constantinople (Figure 19). Dürer went on to incorporate many of the oriental types he collected in Venice into subsequent compositions. Sometimes these could be positive, as in the Map of the Northern Sky he made in 1515. The four corners of Dürer’s print show eminent scientist-philosophers of the ancient world, including, along with Ptolemy of Egypt, ‘Azophi Arabus’ – testimony to the status of Arabic learning. More often, however, such figures function as negative signifiers of the ‘Other’ in his woodcuts and engravings of a variety of biblical scenes. The Martyrdom of Saint John the Evangelist from the Apocalypse series of 1496–8 is notable for its inclusion of a negro and a Jew as well as three turbaned Orientals variously observing and presiding over the Christian saint’s agonies (Figure 20). Western perceptions of Islam during the fifteenth century were perhaps not as one-dimensional and stereotypical as they subsequently became, but for every representation of a scholar or a Renaissance prince, an oriental despot could be found lurking in the shadows of the European imagination.

Gentile Bellini also produced a portrait medal of Mehmet, either during his time in Constantinople or shortly after his return. It was slightly smaller than Costanzo’s, albeit very similar in format, and gave a markedly less robust image of the Sultan. The outstanding work to survive from Gentile’s mission to Constantinople, however, is his oil portrait of Mehmet, dated in its inscription at the bottom right to 25 November 1480 (Figure 14). By this time Mehmet the Conqueror – the title he had assumed on capturing Constantinople a quarter of a century before – was 50 years old and in ill health. He had retired within the confines of the palace, and was principally preoccupied with its decoration and with the cultivation of a garden. He is represented in the painting in the bust-length profile familiar from the medals, and also from the contemporary portraits of the eminent Venetians. The image, however, has a pensive, scholarly air, more marked even than Gentile’s medal, and quite dissimilar to Costanzo’s thicker-set, somewhat belligerent-looking figure. In all three, the sultan is depicted wearing the distinctive Ottoman taj, the turban in which a length of white material is wound around a stiff, ribbed cap in red felt. He also wears a similar garment, a kind of shirt with a cross-over collar, under a deep-red kaftan with a broad fur collar. In the painting, the archway in which he is framed is represented in a western perspectival style, with decoration suggestive of classical candelabra and tracery. But draped over the lintel is an opulent oriental fabric decorated with jewels. Apart from the date, the legible part of the inscription reads ‘Victor Orbis’ – conqueror of the world. The significance of the crowns, for all the prominence of their placement, is unclear. On the reverse of Bellini’s portrait medal there are three of them, usually taken to refer to the three components of the Ottoman Empire – their own original territories in Asia, Greece (including Constantinople) and Trebizond (the Black Sea port and gateway to the Silk Route into central Asia, captured by Mehmet from Venetian control within a decade of the end of Byzantium, in 1461). 54 More recently, however, it has been suggested that the six crowns in Bellini’s oil portrait represent the six previous Ottoman sultans, with Mehmet himself symbolised by the seventh crown, made of pearls, at the bottom centre of the jewelled textile right at the front of the painting. 55

Bellini left Constantinople in January 1481. Mehmet was dead within a year, and his iconoclastic successor sold or destroyed the western-style figurative art he had commissioned for the Topkapý Palace. Legend has it that the sultan’s portrait was bought for a knock-down price in the marketplace by an observant Venetian merchant, and subsequently transported home. Interestingly, however, Bellini’s portrait did leave a trace in Ottoman art. 56 There survives a portrait attributed to Shiblizade Ahmed from the same time which appears to draw on the same pose – the profile portrait, the cross-over collared shirt, the fur-collared Kaftan, the tāj – as well as to employ western shading to suggest volume in areas such as the handkerchief, turban and face, in contrast to the Ottoman convention for flat, unmodelled planes (Figure 21). Where this picture departs from Bellini’s portrait is in the inclusion of the oriental cross-legged sitting posture, and the enigmatic device of having the sultan smell a rose. This is an image which recurs in later Ottoman portraits but whose precise meaning is unclear. One possibility is that it refers to the grace of Paradise; another is simply that Mehmet was renowned for the pleasure he took in the cultivation of his garden.

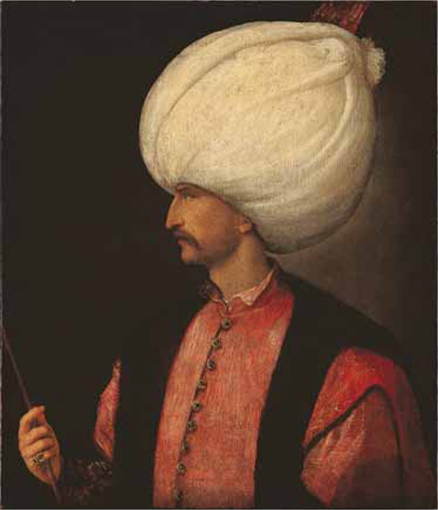

Be that as it may, this story of the image of the Ottoman sultan is inseparable from the larger story of two societies and their interaction – economic, cultural and military. A generation later, when the pressure of the Turks on Christendom reached its highest point, the studio of Titian produced another profile image of a Turkish sultan: Mehmet’s descendant Sulyeman the Magnificent (Figure 22). Probably based on studies by European envoys to the Ottoman court that were intended to be used to illustrate the many printed books on the threat of expansionist Islam, the painted portrait is an arresting image. Headgear had become the principal visual signifier of the ‘Oriental’, and here it reaches a climax. The fact of its authorship by the most eminent workshop of the day, its unstable mix of authority and otherness, of majesty and caricature, says much about the ambiguous power of ‘El Gran Turco’, as he was widely known, in the European imagination of the time. 57

4 Some history paintings

Venetian trade, together with the colonies of merchants established throughout the eastern Mediterranean, meant a constant interplay and importation of ideas and stories as well as objects, textiles and raw materials into Venice itself. The result of the merging of thousands of individual responses was a distinctively inflected society bearing witness to ‘the profound cultural impact of centuries of trade with the Islamic world’. 58 Towards the end of the fifteenth century, and in the early years of the sixteenth, an ‘oriental mode’ became prominent in Venetian pictorial art. In this section I want to look at some examples of this art, but I shall begin with two images of the heart of the city, or rather its hearts plural: the political and religious focus on Piazza San Marco, with the Palazzo Ducale and the Basilica, and the economic and commercial centre of the Venetian empire at Rialto.

I have already touched on the nature of Venetian society, and the way in which a collective ethos held sway. Although nineteenth-century claims about the emergence of a modern sense of the individual as a key to the nature of the Florentine Renaissance are now regarded with scepticism by contemporary historians, the Venetian relationship of the individual to the collective does seem to have been distinctive. The ethos of the ordered totality, enshrined in the ‘Myth of Venice’, encompassing a multiplicity of distinctions, but encompassing and subsuming them nonetheless, is what underwrites the very particular representation embodied in Gentile Bellini’s Procession in the Piazza San Marco of 1496 (Figure 23). Bellini’s piazza is dominated by the façade of the basilica of San Marco, in front of which a procession makes its way from right to left. It might be said that the top half of the picture testifies to the force of the Byzantine and the Gothic in Venice. The domes of the church and the golden mosaics of its portals speak of Byzantium. But interspersed with the Byzantine is the northern – in the form of the Gothic pinnacles at either end and between the pointed arches. The Gothic theme continues in the arches of the Doge’s Palace, visible to the right of the basilica; Islamic influence is apparent in the pink and white lozenge-shapes of its decorative tile work. This lack of fortification on its seat of government, the large windows and the pervasive decoration serve to underline Venetian pre-eminence: a city so powerful, so replete with divine grace, that it did not need walls.

Bellini’s picture was originally painted for the meeting room of the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista, whose members process across the front of the square. The organised quality of the painted representation stands unequivocally for the ordered nature of Venetian society – its diversity rendered equal in the sight of the church. The doge is one of a crowd, halfway along the right-hand side of the square. The other scuole have finished their processions and are drawn up in orderly fashion to the left. The middle of the picture offers nothing less than ‘a demographic cross-section of Venice’. 59 Along with ladies, gentlemen and citizens in recognisable costumes can be seen a group of German merchants in the middle distance to the right of the canopy, four Greek merchants in their distinctive black-brimmed hats standing in the middle of the square to the left; in the distance, in front of the basilica to the right are three turbaned Turks. In the row of first-floor windows along the far left of the square, well-dressed women, two of them apparently veiled in Islamic style, look out from balconies, over which are draped more than 30 rich oriental carpets.

The real subject of the picture is, however, none of this urban spectacle. Or rather it is all of it, in balance with a single defining motif of divine intervention in the secular domain. The point of the commission as a whole, of all nine paintings in the scuola’s great albergo, or meeting room, is to commemorate the Miracles of the True Cross. Throughout Renaissance Europe, and nowhere more so than in Venice, holy relics marked the borders of the mundane and the divine – in fact the miracles they performed were the proof of the presence of the divine in the material world below. The Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista’s prize possession was a fragment of the True Cross, donated in the previous century by the Grand Chancellor of Cyprus, who had in turn received it from the Patriarch of Constantinople. The albergo itself was in effect the frame for the wooden fragment housed in its gold reliquary, which was taken out and borne in procession on key feast days – such as the one depicted here: 25 April, the feast day of Saint Mark, patron saint of Venice. The key figure is a merchant from Brescia, in Venice for the vigil, and doubtless also on business. While there, he receives notice of a near fatal accident to his son. The boy will not survive. The merchant, just visible through a gap in the procession to the right of centre, kneels and prays to God for his son’s survival as the relic of the True Cross passes by. On his return to Brescia, he finds the boy healed: a miracle. God’s presence in the world is confirmed again. This is what Bellini represents: the divine at work in the cosmopolitan life of Venice.

Something of the same holds for another picture originally part of the same cycle in the Scuola’s meeting room, painted by Vittore Carpaccio two years earlier (Figure 24). Here, Carpaccio depicts another miracle, this time in the economic and commercial heart of Venice, the Rialto, adjacent to the busy Grand Canal. Once again the key to the picture is displaced to the margins, the sacred being embedded in the flow of secular life. At the far left, in the first-floor loggia, an exorcism is taking place. A possessed man is being healed by the miracle-working fragment of the True Cross, as commercial and social life rolls on with barely a blink. Another varied cast of characters is discernible. Along the bank of the canal, immediately before the bridge, can just be seen the columns of an open loggia where the merchants met. Outside it, two white-turbanned figures in long robes, one white, one orange, can just be made out. In the foreground, at the far left, in black-brimmed hats and sumptuous brocade robes, stand figures thought to be Armenian or Greek merchants. And unmissable, right in the centre foreground and acting as a kind of counter-focus to the decentred miracle, is a working man, albeit no ordinary workman: a distinctively attired African gondolier. This gondolier was most likely a slave. 60

Venice had traded in slaves since at least the tenth century, probably earlier. 61 Most were Christians, often described as ‘Tartars’ or ‘Circassians’ from the area around the Black Sea. After the fall of Constantinople, there was a decline in this Black Sea slave trade (not that the traffic died out – they were simply used by the Ottomans), and an increase in the use of black slaves from Africa. These numbers increased further in the sixteenth century as European attitudes turned against the enslavement of fellow Christians, and increasing Ottoman power militated against the use of Muslim slaves. It has been calculated that in the late fifteenth century perhaps 1,500 negro slaves were being traded annually at Venice. 62 By 1600, however, Venetian slavery had died out – not least because of competing demand from Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, British and French colonies, as well as the Muslim states. After that time freed slaves continued to live in Venice, mostly though not exclusively working as domestic servants. Although Africans were never as numerous as other communities, such as Jews, Turks and Germans, the imagery of black people entered into Venetian popular culture and has never really left it (as the Fred Wilson installation mentioned at the start of this chapter testifies).

In the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, the fondaco of the merchants from Dalmatia, between 1502 and 1508 Carpaccio painted three scenes from the life of Saint George as part of an overall scheme of nine pictures. Whereas the two paintings from San Giovanni Evangelista represent the diversity of Venetian society itself, these pictures form part of an overtly ‘oriental mode’ in Venetian art. The narrative mode as a whole functioned to represent the ‘Myth of Venice’ back to Venetians themselves, a visual counterpart to the historical chronicles which narrated the city’s foundation and prosperity. 63 In the late fifteenth century, contemporary political developments seem to have stimulated artists to address a newly pressing theme, namely the ‘Other’ to Venice’s imperium in the shape of expansionist Islam. In these works certain Venetian artists ‘attempted to reproduce an Islamic setting, with figures dressed in Muslim garb, exotic animals – camels, monkeys and giraffes – and, on occasion, architecture of Islamic inspiration’. 64 In contrast to Bellini’s portrait of Mehmet II, or his individual costume studies, these pictures involve a conscious attempt to imagine an oriental culture and society.

The representation of the world of Islam takes, however, a specific form. One curious feature of this development is that Venetian artists seem to have shied away from representing contemporary Ottoman society as such. Whereas verbal reports on Ottoman society abounded, and although isolated Ottoman figures can be found in Venetian art, sometimes situated in the heart of Venice itself, there are no images of the lived environment of the Ottoman world. What there are, however, are plentiful images of the early Christian world of the Holy Land. And in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries the Holy Land lay not in Ottoman territory but in the empire of the Mamluks, the other eastern Mediterranean Islamic culture, based in present-day Syria and Egypt. So Venetian artists, representing the trials and victories of the early Christian Church, imagined them against a partly factual, partly made-up background of known architecture and non-Christians in Mamluk costume.

Thus, Carpaccio’s The Triumph of Saint George (Figure 25) shows a miscellaneous crowd of Mamluk figures witnessing the triumph of the Christian knight against a background of buildings based on woodcut images of the Dome of the Rock and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Traditionally, the Saint George story was set in the Eastern Christian Empire, including Palestine. The dragon motif was established in the thirteenth-century Golden Legend, wherein the killing of the dragon results in the conversion of the people to Christianity. It does not take an enormous leap of the imagination to read the dragon that is about to succumb to George’s coup de grâce as a figure for the pagan unbelief that the Church is poised to overcome. This reading is reinforced in the final painting of the series, Saint George Baptising the Pagans (Figure 26). To the left, musicians wearing the Mamluk zamt, a tufted bonnet, stand on a plinth covered in an Islamic carpet; to the right, conspicuously bare-headed figures are baptised into the Christian faith, their elaborate Mamluk headgear cast aside at the foot of the stairs they have mounted.

The meeting house of the Dalmatian confraternity of Saint George was in a building owned by the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem, themselves a crusader organisation. The Dalmatians had been in the frontline of the Venetian struggle against the Turks in the Adriatic, and their presence in Venice marked them as, essentially, refugees from Ottoman expansion. The occasion of the commission to decorate the meeting room was their receipt of an important relic of Saint George in honour of their exploits under the flag of Venice. This was a gift from the commander of the Venetian forts in Dalmatia before they fell to the Turks in 1499, who in turn had received it from no less a figure than the Patriarch of Jerusalem. It can readily be seen, therefore, how the Saint George legend of the defeat of pagan unbelief by the action of a virtuous Christian knight becomes a resonant motif at a point where Venetian Christian culture perceives itself threatened by the apparently unstoppable expansion of the Islamic Ottoman Empire.

A similar cluster of concerns underwrites the enormous painting by Gentile Bellini of Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria (Figure 27). This picture turned out to be Gentile’s last, and although the design and most of the actual work is his, some of the foreground figures and the buildings to right and left of the central square were completed after his death by his brother Giovanni. The Scuola Grande di San Marco had been rebuilding its premises after a fire in 1485, and Bellini put himself forward to decorate the albergo as early as 1492. The commission, however, was not finalised until 1504, by which time Bellini had behind him the success of his Procession in the Piazza San Marco. The new painting was intended to evoke that earlier triumph, and was indeed ‘specifically cited as the standard which he promised to surpass’. 65 The added ingredient in this commission, of course, is that Saint Mark is the patron saint of Venice itself. Preaching to the infidel (and, indeed, dying for the cause) represents a powerful ideological message in early sixteenth century Venice.

This was not the first work to dramatise Saint Mark’s attempts to win over the infidels in a plausibly Egyptian setting: precedence goes to a project of the late 1490s by Cima da Conegliano and Giovanni Mansueti for the silk-weavers guild. Indeed, Mansueti (active 1485–1526/7) went on to work on the Scuole di San Marco commission after Gentile’s death, with three further orientalising paintings on episodes from the life of Saint Mark (Figure 28). Mansueti’s rather cluttered paintings draw on what was by then an established repertoire of motifs, including a variety of eastern headgear and the Mamluk coat of arms, albeit set in unlikely classical architecture. By contrast, in the grandeur of its conception and coherence of design, Gentile’s picture of Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria represents a culmination of the orientalist mode in Venetian painting. Taken in conjunction with the Procession in the Piazza San Marco, it represents a kind of mapping of Venice onto its ‘Other’: the Piazza San Marco onto the Alexandrian plaza, the basilica onto the imaginary pagan temple. It is as if by assimilating the exotic – and threatening – to the familiar, the all-too real threat of the Islamic ‘Other’ could be negotiated and absorbed at the level of the imagination.