What is heritage?

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 19 April 2024, 6:33 PM

What is heritage?

Introduction

This course introduces the concept of heritage and examines its various uses in contemporary society. It then provides a background to the development of critical heritage studies as an area of academic interest, and in particular the way in which heritage studies has developed in response to various critiques of contemporary politics and culture in the context of deindustrialisation, globalisation and transnationalism. Drawing on a case study in the official documentation surrounding the Harry S. Truman Historic Site in Missouri, USA, it describes the concept of authorised heritage discourses (AHD) in so far as they are seen to operate in official, state-sanctioned heritage initiatives.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 2 study in Arts and Humanities.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand the global scope of heritage

understand the ‘material’ and ‘non-material’ aspects of heritage

recognise heritage as a ‘process’ as well as a ‘product’ of certain activities in the present

recognise heritage studies as a specific field of study

understand the idea of the authorised heritage discourse (AHD).

1 Introducing heritage

This course introduces the concept of heritage and examines its various uses in contemporary society. It then provides a background to the development of critical heritage studies as an area of academic interest, and in particular the way in which heritage studies has developed in response to various critiques of contemporary politics and culture in the context of deindustrialisation, globalisation and transnationalism. Drawing on a case study in the official documentation surrounding the Harry S. Truman Historic Site in Missouri, USA, it describes the concept of authorised heritage discourses (AHD) in so far as they are seen to operate in official, state-sanctioned heritage initiatives. Where the other chapters in the book contain substantial case studies as part of the discussion of the different aspects of the politics of heritage, this course focuses instead on key concepts, definitions and ideas central to understanding what heritage is, and on heritage studies as a field of inquiry. The chapter suggests that critical heritage studies should be concerned with these officially sanctioned heritage discourses and the relationships of power they facilitate on the one hand, and the ways in which heritage operates at the local level in community and identity building on the other.

We will be introducing you to the meaning of ‘heritage’ in global societies. But first, I would like you to think about what the word heritage means to you.

Activity 1

Using a notebook or a tablet, write down some key words that spring to mind when you think of the term ‘heritage’. Now try to write down some of the sorts of things that you think could be described as heritage. Save this list so that you can refer to it later on.

Discussion

Summing up what you think heritage is may not have been as easy as you thought it might be. Perhaps you wrote down something about ‘the past’ and ‘old buildings’, or something about places, objects or buildings that have some form of protection. You may have written down the word ‘history’. It is impossible to capture the diverse range of meanings of heritage in such a short space of time.

Activity 2

Now let’s look at the ways in which a dictionary defines heritage.

Using a dictionary, physical or online, search for the word ‘heritage’ and make a note of the definition provided.

Discussion

One of the meanings of ‘heritage’ offered by the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is ‘characterized by or pertaining to the preservation or exploitation of local and national features of historical, cultural, or scenic interest, esp. as tourist attractions’, but there are several other meanings of the word, including ‘inheritance’ and ‘lineage’.

2 Explaining heritage

This course begins with two photographs: a picture of the Great Barrier Reef in Australia (Figure 1) and a picture of the Mir Castle complex in Belarus (Figure 2).

The photographs appear to show very different types of place, in locations that are widely geographically spaced. One of these is a ‘natural’ place, the other is humanly made (a building, albeit a very grand one). In what ways might we characterise the similarities between the two places? What qualities can we find that link them?

Although they are very different, both of these places are considered to be ‘heritage’, indeed ‘World’ heritage, and both are listed on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage List. This course concentrates on the ways in which these two very different entities, in two very different places, can both be understood as ‘heritage’.

A bird’s-eye view of the line of the reef stretching diagonally upwards from the lower left corner of the photograph. Above is a vista of pools and sandbanks, with a channel crossing it right to left, stretching into the distance. There is a small cluster of pleasure boats moored by the edge of the reef, and another boat a little further away.

The Great Barrier Reef is the world’s most extensive stretch of coral reef. The reef system, extending from just south of the Tropic of Capricorn to the coastal waters of Papua New Guinea, comprises some 3400 individual reefs, including 760 fringing reefs, which range in size from under 1 ha to over 10,000 ha and extend for more than 2000 km off the east coast of Australia. The Great Barrier Reef includes a range of marine environments and formations, including approximately 300 coral cays and 618 continental islands which were once part of the mainland. The reef is home to a number of rare and endangered animal and plant species and contains over 1500 species of fish, 400 species of coral, 4000 species of mollusc and 242 species of birds plus a large number of different sponges, anemones, marine worms and crustaceans and other marine invertebrates. The reef includes feeding grounds for dugongs, several species of whales and dolphins, and nesting grounds of green and loggerhead turtles (United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre, 2008).

A summer day – people are in shirtsleeves – with large crowds around the massive complex of Mir Castle. The castle appears to be residential rather than defensive, built round a square enclosed courtyard, with chunky square bastions at the corners surmounted by octagonal towers topped by squat spires. In the foreground, on the edge of the grass and beside the path, vendors offer pictures and souvenirs for sale.

The Mir Castle complex is situated on the bank of a small lake at the confluence of the river Miryanka and a small tributary in the Grodno Region of what is now known as the Republic of Belarus. The castle was built in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century in a style that architects familiar with the form it took in central Europe would recognise as ‘Gothic’. It was subsequently extended and reconstructed, first in ‘Renaissance’ and then in ‘Baroque’ styles. The castle sustained severe damage during Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812 and was abandoned as a ruin. It was subsequently restored at the end of the nineteenth century, at which time the surrounding parkland received extensive landscaping. Mir Castle is considered to be an exceptional example of a central European castle, reflecting in its design and layout successive cultural influences (Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque) as well as the political and cultural conflicts that characterise the history of the region (UNESCO, 2008).

What makes these places ‘heritage’? And what makes them part of the world’s heritage? The process of nominating a place for inclusion on the World Heritage List involves an assessment of the ways in which a place meets a particular set of criteria for inclusion. This argument is developed by a body representing the sovereign state of the territory in which the site exists and is submitted to a committee in charge of assessing the nominations. Although it would be possible to look in detail at the criteria for inclusion, and at the values implicit in the criteria, it is clear that these sites are defined as heritage by the sheer fact that they have been classified as such through inclusion on a heritage register. This process by which an object, place or practice receives formal recognition as heritage and is placed on a heritage register can be termed an ‘official’ heritage process. Once places become statutory entities and are recognised as belonging to heritage by their inclusion on an official heritage list, they are ‘created’ as ‘official heritage’ and subject to a series of assumptions about how they must be treated differently from other places. For example, official heritage places must be actively managed and conserved, and there is an expectation that funding must be allocated to them so that this can occur.

Although both of these places are recognised through their listing as belonging to the world’s heritage, they have a range of different meanings for the local people who interact with them on an everyday basis. For example, the Barrier Reef, which is understood to be World Heritage on the basis of its biodiversity and recreational values, is a source of sustenance, livelihood and spiritual inspiration for the many different groups of Indigenous Australians who live along the Queensland coastline. They would traditionally understand their relationship with the reef as one of custodianship and the right to control access, hunt, fish and gather in its environs. Clearly the reef’s promotion as a World Heritage site implies that it is ‘owned’ (at least culturally) not only by local people but also by the world community. So there is the potential for a range of different ways of relating to, understanding the significance of, and giving meaning to heritage objects, sites and practices. This range of values of heritage may not be well catered for within traditional western models of heritage and official definitions of heritage. In this case, such differences may give rise to conflict over who has the right to determine access and management of different parts of the reef. Indeed, in most cases the official and the local would be thought of as competing forms of heritage. Heritage itself is a dynamic process which involves competition over whose version of the past, and the associated moral and legal rights which flow from this version of the past, will find official representation in the present.

This brief example embodies the two inter-related understandings of heritage that form the central focus of this book: the largely ‘top-down’ approach to the classification and promotion of particular places by the state as an embodiment of regional, national or international values which creates ‘official’ heritage; and the ‘bottom-up’ relationship between people, objects, places and memories which forms the basis for the creation of unofficial forms of heritage (usually) at the local level. Critical heritage studies, in its most basic sense, involves the investigation of these two processes and the relationship between them. Heritage studies is an exciting new interdisciplinary field of inquiry which draws on a range of academic disciplines and skills including history, archaeology, anthropology, sociology, art history, biology, geography, textual analysis and visual discrimination, to name but a few. The aim of this book is to form an introduction to heritage as a global concept, and critical heritage studies as a field of inquiry.

2.1 What is heritage?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines ‘heritage’ as ‘property that is or may be inherited; an inheritance’, ‘valued things such as historic buildings that have been passed down from previous generations’, and ‘relating to things of historic or cultural value that are worthy of preservation’. The emphasis on inheritance and conservation is important here, as is the focus on ‘property’, ‘things’ or ‘buildings’. So (according to the Oxford English Dictionary, anyway), heritage is something that can be passed from one generation to the next, something that can be conserved or inherited, and something that has historic or cultural value. Heritage might be understood to be a physical ‘object’: a piece of property, a building or a place that is able to be ‘owned’ and ‘passed on’ to someone else.

In addition to these physical objects and places of heritage there are also various practices of heritage that are conserved or handed down from one generation to the next. Language is an important aspect of who we understand ourselves to be, and it is learned and passed from adult to child, from generation to generation. These invisible or ‘intangible’ practices of heritage, such as language, culture, popular song, literature or dress, are as important in helping us to understand who we are as the physical objects and buildings that we are more used to thinking of as ‘heritage’. Another aspect of these practices of heritage is the ways in which we go about conserving things – the choices we make about what to conserve from the past and what to discard: which memories to keep, and which to forget; which memorials to maintain, and which to allow to be demolished; which buildings to save, and which ones to allow to be built over. Practices of heritage are customs and habits which, although intangible, inform who we are as collectives, and help to create our collective social memory. We use objects of heritage (artefacts, buildings, sites, landscapes) alongside practices of heritage (languages, music, community commemorations, conservation and preservation of objects or memories from the past) to shape our ideas about our past, present and future.

Another way of thinking about this distinction between objects of heritage and practices of heritage is to consider the different perspectives through which heritage is perceived. For every object of heritage there are also heritage practices. However one group of people (say, professional heritage managers) respond to heritage, other people may respond differently. Thus, around an object of heritage, there may be value judgements based on ‘inherent’ qualities (which may indeed play a determining role in designating the object and conserving it), but there may well be other values which drive the use of the object (associations of personal or national identity, associations with history, leisure etc., as in the example of designation of Harry S. Truman’s otherwise humble dwelling as a National Historic Site discussed later in this course). For every object of tangible heritage there is also an intangible heritage that ‘wraps’ around it – the language we use to describe it, for example, or its place in social practice or religion. Objects of heritage are embedded in an experience created by various kinds of users and the people who attempt to manage this experience. An analogous situation exists in the art world in understanding aesthetics. There is no art without the spectator, and what the spectator (and critic) makes of the art work sits alongside what the artist intended and what official culture designates in a discursive and often contested relationship. So in addition to the objects and practices of heritage themselves, we also need to be mindful of varying ‘perspectives’, or subject positions on heritage.

The historian and geographer David Lowenthal has written extensively on the important distinction between heritage and history. For many people, the word ‘heritage’ is probably synonymous with ‘history’. However, historians have criticised the many instances of recreation of the past in the image of the present which occur in museums, historic houses and heritage sites throughout the world, and have sought to distance themselves from what they might characterise as ‘bad’ history. As Lowenthal points out in The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History, heritage is not history at all: ‘it is not an inquiry into the past, but a celebration of it ... a profession of faith in a past tailored to present-day purposes’ (Lowenthal, 1997, p. x). Heritage must be seen as separate from the pursuit of history, as it is concerned with the re-packaging of the past for some purpose in the present. These purposes may be nationalistic ones, or operate at the local level.

‘Heritage’ also has a series of specific and clearly defined technical and legal meanings. For example, the two places discussed earlier in this course are delineated as ‘heritage’ by their inclusion on the World Heritage List. As John Carman (2002, p. 22) notes, heritage is created in a process of categorising. These places have an official position that has a series of obligations, both legal and ‘moral’, arising from their inclusion on this register. As places on the World Heritage List they must be actively conserved, they should have formal documents and policies in place to determine their management, and there is an assumption that they will be able to be visited so that their values to conservation and the world’s heritage can be appreciated.

There are many other forms of official categorisation that can be applied to heritage sites at the national or state level throughout the world. Indeed, heritage as a field of practice seems to be full of lists. The impulse within heritage to categorise is an important aspect of its character. The moment a place receives official recognition as a heritage ‘site’, its relationship with the landscape in which it exists and with the people who use it immediately changes. It somehow becomes a place, object or practice ‘outside’ the everyday. It is special, and set apart from the realm of daily life. Even where places are not officially recognised as heritage, the way in which they are set apart and used in the production of collective memory serves to define them as heritage. For example, although it might not belong on any heritage register, a local sports arena might be the focus for collective understandings of a local community and its past, and a materialisation of local memories, hopes and dreams. At the same time, the process of listing a site as heritage involves a series of value judgements about what is important, and hence worth conserving, and what is not. There is a dialectical relationship between the effect of listing something as heritage, and its perceived significance and importance to society.

Some authors would define heritage (or at least ‘official’ heritage) as those objects, places and practices that can be formally protected using heritage laws and charters. The kinds of heritage we are most accustomed to thinking about in this category are particular kinds of objects, buildings, towns and landscapes. One common way of classifying heritage is to distinguish between ‘cultural’ heritage (those things manufactured by humans), and ‘natural’ heritage (those which have not been manufactured by humans). While this seems like a fairly clear-cut distinction, it immediately throws up a series of problems in distinguishing the ‘social’ values of the natural world. Returning to the example of the Great Barrier Reef discussed earlier in this course, for the Indigenous Australians whose traditional country encompasses the reef and islands, the natural world is created and maintained by ‘cultural’ activities and ceremonies involving some aspects of intangible action such as song and dance, and other more practical activities such as controlled burning of the landscape and sustainable hunting and fishing practices. It would obviously be extremely difficult to characterise these values of the natural landscapes to Indigenous Australians using a system that divides ‘cultural’ and ‘natural’ heritage and sees the values of natural landscapes as being primarily ecological.

Heritage is in fact a very difficult concept to define. Most people will have an idea of what heritage ‘is’, and what kinds of thing could be described using the term heritage. Most people, too, would recognise the existence of an official heritage that could be opposed to their own personal or collective one. For example, many would have visited a national museum in the country in which they live but would recognise that the artefacts contained within it do not describe entirely what they would understand as their own history and heritage. Clearly, any attempt to create an official heritage is necessarily both partial and selective. This gap between, on one hand, what an individual understands to be their heritage and, on the other hand, the official heritage promoted and managed by the state introduces the possibility of multiple ‘heritages’. It has been suggested earlier that heritage could be understood to encompass objects, places and practices that have some significance in the present which relates to the past.

In 2002 during the United Nations year for cultural heritage, UNESCO produced a list of ‘types’ of cultural heritage (UNESCO, n.d.). This is one way of dividing and categorising the many types of object, place and practice to which people attribute heritage value. It should not be considered an exhaustive list, but it gives a sense of the diversity of ‘things’ that might be considered to be official heritage:

- cultural heritage sites (including archaeological sites, ruins, historic buildings)

- historic cities (urban landscapes and their constituent parts as well as ruined cities)

- cultural landscapes (including parks, gardens and other ‘modified’ landscapes such as pastoral lands and farms)

- natural sacred sites (places that people revere or hold important but that have no evidence of human modification, for example sacred mountains)

- underwater cultural heritage (for example shipwrecks)

- museums (including cultural museums, art galleries and house museums)

- movable cultural heritage (objects as diverse as paintings, tractors, stone tools and cameras – this category covers any form of object that is movable and that is outside of an archaeological context)

- handicrafts

- documentary and digital heritage (the archives and objects deposited in libraries, including digital archives)

- cinematographic heritage (movies and the ideas they convey)

- oral traditions (stories, histories and traditions that are not written but passed from generation to generation)

- languages

- festive events (festivals and carnivals and the traditions they embody)

- rites and beliefs (rituals, traditions and religious beliefs)

- music and song

- the performing arts (theatre, drama, dance and music)

- traditional medicine

- literature

- culinary traditions

- traditional sports and games.

Some of the types of heritage are objects and places (‘physical’ or ‘material’ heritage) while others are practices (‘intangible’ heritage). However, many of these categories cross both types of heritage. For example, ritual practices might involve incantations (intangible) as well as ritual objects (physical). So we should be careful of thinking of these categories as clear cut or distinct. In addition, this list only includes ‘cultural’ heritage. Natural heritage is most often thought about in terms of landscapes and ecological systems, but it is comprised of features such as plants, animals, natural landscapes and landforms, oceans and water bodies. Natural heritage is valued for its aesthetic qualities, its contribution to ecological, biological and geological processes and its provision of natural habitats for the conservation of biodiversity. In the same way that we perceive both tangible and intangible aspects of cultural heritage, we could also speak of the tangible aspects of natural heritage (the plants, animals and landforms) alongside the intangible (its aesthetic qualities and its contribution to biodiversity).

Another aspect of heritage is the idea that things tend to be classified as ‘heritage’ only in the light of some risk of losing them. The element of potential or real threat to heritage – of destruction, loss or decay – links heritage historically and politically with the conservation movement. Even where a building or object is under no immediate threat of destruction, its listing on a heritage register is an action which assumes a potential threat at some time in the future, from which it is being protected by legislation or listing. The connection between heritage and threat will become more important in the later part of this course.

Heritage is a term that is also quite often used to describe a set of values, or principles, which relate to the past. So, for example, it is possible for a firm of estate agents to use the term in its name not only to mean that it markets and sells ‘heritage’ properties, but also simultaneously to invoke a series of meanings about traditional values which are seen as desirable in buying and selling properties. We can also think here about the values which are implicit in making decisions about what to conserve and what not to conserve, in the choices we make about what we decide to label ‘heritage’ and what view as simply ‘old’ or ‘outdated’. These values are implicit in cultural heritage management.

2.2 Governments, heritage registers and the ‘canon’

One aspect of understanding heritage is appreciating the enormous influence of governments in managing and selectively promoting as heritage certain aspects of the physical environment and particular intangible practices associated with culture. One way in which governments are involved in heritage is through the maintenance, funding and promotion of certain places as tourist destinations. We are also reminded here, for example, of the many ways in which governments and nations are involved in the preservation of language as a way of preserving heritage and culture. Language is promoted and controlled by governments through official language policies which determine the state language and which often specify certain controls on the use of languages other than the state language. For example, in France, the ‘Toubon’ Law (Law 94-665, which came into force in 1994 and is named for the minister of culture, Jacques Toubon who suggested and passed the law through the French parliament) specifies the use of the French language in all government publications, print advertisements, billboards, workplaces, newspapers, state-funded schools and commercial contracts. We might also think of the suggestion by French president Nicolas Sarkozy (president 2007–) in 2008 that the correct methods for preparing classic items of French cuisine might be considered for protection as part of the UNESCO World Heritage List. At the time of writing, the nomination is still in preparation for presentation to the UNESCO World Heritage Committee.

In addition to such policies which ensure the preservation of intangible aspects of cultural heritage, governments play a major role in the maintenance and promotion of lists or databases of heritage. Most countries have a ‘national’ heritage list of physical places and objects which are thought to embody the values, spirit and history of the nation. In addition, governments may have multi-layered systems of heritage which recognise a hierarchy of heritage places and objects of national, regional and local significance. These lists (and indeed, the World Heritage List discussed earlier) might be thought of as offshoots of the concept of ‘the canon’. The word ‘canon’ derives from the Greek word for a rule or measure, and the term came to mean the standard by which something could be assessed. The idea of a canon of works of art developed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to describe a body of artistic works that represent the height of aesthetic and artistic merit – works of art judged by those who are qualified in matters of taste and aesthetics to be ‘great’ works of art. Similarly, a literary canon describes those writers and their works that are deemed to be ‘great literature’. The canon is a slippery concept, as it is not defined specifically, but through a process of positioning – the canon is represented by those works of art that are held in art galleries and museums and discussed in art books, and those works of literature that are cited in literary anthologies.

When we start to think of a list of heritage as a sort of canon it raises a number of questions. Who are the people who determine what is on the list and what is not? What values underlie the judgements that specify which places and objects should be represented? How do we assess which are the great heritage objects and places and which are not? How does creating such a list include and exclude different members of society? It is now widely recognised that the idea of a canon is linked closely with that of nation (Mitchell, 2005), and that canons might be understood to represent ideological tools that circulate the values on which particular visions of nationhood are established. Creation of a class of ‘things’ that are seen to be the greatest expressions of culture promotes, in turn, narratives about the set of values that are seen to be the most worthy in the preservation of a particular form of state society. The heritage list, like the literary or artistic canon, is controlled by putting the power to establish the canon into the hands of experts who are sanctioned by the state.

It is important to point out that heritage is a rather strange kind of canon. It is unlike the canon of modern art as it is usually understood, for example, since the criteria that constitute it are diverse rather than unified. Modern art is defined by current canons of taste and these create separate ‘canons’ for different ideologies, such as a feminist canon, or a social history of art canon. These can co-exist, but each maintains its own consistent identity. The heritage canon, if measured by the World Heritage List (or a national heritage list) finishes up as a single list, but one which is determined by a wide range of considerations.

It is also important to make the point that heritage is fundamentally an economic activity. This is easily overlooked in critical approaches that focus on the role of heritage in the production of state ideologies (Ashworth et al., 2007, p. 40). Much of what motivates the involvement of the state and other organisations in heritage is related to the economic potential of heritage and its connections with tourism. The relationship between heritage and tourism is examined later in this course, but it would be remiss to neglect a mention here of the economic imperative of heritage for governments.

Activity 3

Now that you have finished reading the first few pages, which describe what heritage is, take another look at the notes you made in Activity 1. Are there any essential characteristics of heritage that you would add to your original list? I hope the reading has stimulated you to think about a number of ‘things’ that might be considered to be heritage that were not on your original list.

Discussion

One aspect of heritage that you may not have noted down in your original list is the practices of heritage, which include intangible customs and traditions, such as language, oral tradition and memory. If you compare your responses to this activity with the OED definition of heritage that you read in the discussion for Activity 2, you will notice that even the best dictionary will only include a limited definition of a topic as complex and controversial as heritage. Throughout this course, you will come to appreciate that it is the very diversity of views around what constitutes heritage which is at the heart of heritage studies as an academic discipline. This diversity is often expressed in the different values that people attribute to heritage objects, places and practices.

3 ‘There is no such thing as heritage’

The first part of this course presented a range of definitions of heritage that derive from everyday and technical uses of the term. Here a series of approaches to heritage are introduced by way of a particular academic debate about heritage. Given the focus on preservation and conservation, heritage as a professional field has more often been about ‘doing’ than ‘thinking’; it has focused more on technical practices of conservation and processes of heritage management than on critical discussion of the nature of heritage and why we think particular objects, places and practices might be considered more worthy than others of conservation and protection. But more recently scholars have begun to question the value of heritage and its role in contemporary society. Archaeologist Laurajane Smith, who has written extensively in the field of critical heritage studies, writes ‘there is, really, no such thing as heritage’ (2006, p. 11). What could she mean by this statement? How can there be legislation to protect heritage if it does not, in some way, exist!

In making this bold statement, Smith is drawing on a much older debate about heritage that began in the UK during the 1980s. This debate has been very influential in forming the field of critical heritage studies as it exists today, not only in the UK, but throughout the parts of the world in which ‘western’ forms of heritage conservation operate, and in the increasingly large numbers of ‘non-western’ countries who are engaged in a global ‘business’ of heritage through the role of the World Heritage List in promoting places of national importance as tourist destinations. The next section outlines this debate and the ideas that have both fed into and developed from it, as an introduction to critical heritage studies as a field of academic research (this characterisation of the debate is strongly influenced by Boswell, 1999).

3.1 The heritage ‘industry’

In the late 1980s English academic Robert Hewison coined the phrase ‘heritage industry’ to describe what he considered to be the sanitisation and commercialisation of the version of the past produced as heritage in the UK. He suggested that heritage was a structure largely imposed from above to capture a middle-class nostalgia for the past as a golden age in the context of a climate of decline.

Hewison believed that the rise of heritage as a form of popular entertainment distracted its patrons from developing an interest in contemporary art and critical culture, providing them instead with a view of culture that was finished and complete (and firmly in the past). He pointed to the widespread perception of cultural and economic decline that became a feature of Britain’s perception of itself as a nation in the decades following the Second World War:

In the face of apparent decline and disintegration, it is not surprising that the past seems a better place. Yet it is irrecoverable, for we are condemned to live perpetually in the present. What matters is not the past, but our relationship with it. As individuals, our security and identity depend largely on the knowledge we have of our personal and family history; the language and customs which govern our social lives rely for their meaning on a continuity between past and present. Yet at times the pace of change, and its consequences, are so radical that not only is change perceived as decline, but there is the threat of rupture with our past lives.

The context in which Hewison was writing was important in shaping his criticism of heritage as a phenomenon. His book The Heritage Industry is as much a reflection on the changes that occur within a society as a result of deindustrialisation, globalisation and transnationalism (in particular, the impact of rapid and widespread internal migration and immigration on the sense of ‘rootedness’ that people could experience in particular places in the UK in the 1980s, and the nostalgia that he saw as a response to this sense of uprootedness) as it is a criticism of heritage itself. He noted that the postwar period in the UK coincided with a period of growth in the establishment of museums and in a widespread sense of nostalgia, not for the past as it was experienced but for a sanitised version of the past that was re-imagined through the heritage industry as a Utopia, in opposition to the perceived problems of the present:

The impulse to preserve the past is part of the impulse to preserve the self. Without knowing where we have been, it is difficult to know where we are going. The past is the foundation of individual and collective identity, objects from the past are the source of significance as cultural symbols. Continuity between past and present creates a sense of sequence out of aleatory chaos and, since change is inevitable, a stable system of ordered meanings enables us to cope with both innovation and decay. The nostalgic impulse is an important agency in adjustment to crisis, it is a social emollient and reinforces national identity when confidence is weakened or threatened.

The academic Patrick Wright had published a book some two years earlier than The Heritage Industry titled On Living in an Old Country (1985). Like Hewison, Wright was concerned with the increasing ‘museumification’ of the UK, and the ways in which heritage might act as a distraction from engaging with the issues of the present. Wright argued that various pieces of heritage legislation that were put forward by the Conservative government could be read as the revival of the patriotism of the Second World War, and connected this Conservative patriotism to the events of the Falklands conflict. Like Hewison, he was also critical of the ‘timelessness’ of the presentation of the past formed as part of the interpretation of heritage sites:

National heritage involves the extraction of history – of the idea of historical significance and potential – from a denigrated everyday life and its restaging or display in certain sanctioned sites, events, images and conceptions. In this process history is redefined as ‘the historical’, and it becomes the object of a similarly transformed and generalised public attention ... Abstracted and redeployed, history seems to be purged of political tension; it becomes a unifying spectacle, the settling of all disputes. Like the guided tour as it proceeds from site to sanctioned site, the national past occurs in a dimension of its own – a dimension in which we appear to remember only in order to forget.

These critiques of heritage in the UK centred on the ways in which heritage distracted people from engaging with their present and future. Both authors employed a ‘bread and circuses’ analogy in arguing that heritage, like the popular media, was a diversion which prevented people from engaging with the problems of the present:

Heritage ... has enclosed the late twentieth century in a bell jar into which no ideas can enter, and, just as crucially, from which none can escape. The answer is not to empty the museums and sell up the National Trust, but to develop a critical culture which engages in a dialogue between past and present. We must rid ourselves of the idea that the present has nothing to contribute to the achievements of the past, rather, we must accept its best elements, and improve on them ... The definition of those values must not be left to a minority who are able through their access to the otherwise exclusive institutions of culture to articulate the only acceptable meanings of past and present. It must be a collaborative process shared by an open community which accepts both conflict and change.

We need to pause to make a distinction between two criticisms of heritage which seem bound together here. There is a criticism of false consciousness of the past – the presentation of the past in an inaccurate manner – which can be corrected or remedied by ‘better’ use of history in heritage interpretation. There is also a criticism of nostalgia and anxiety that may be produced by an accurate understanding of past historical events (world wars, loss of empire and its influence etc.) but that direct attention away from the future. It needs to be kept in mind that nostalgia is separate from false consciousness. No matter how accurately history is represented by heritage, it can always be directed towards particular ends. The problem with official forms of heritage is not so much that it is ‘bogus history’ but that it is often directed towards establishing particular national narratives in reaction to the influence of globalisation on the one hand, and the local on the other. We can see the growth of heritage in the second part of the twentieth century as, at least in part, a reaction to the way in which globalisation, migration and transnationalism had begun to erode the power of the nation-state. In this guise, heritage is primarily about establishing a set of social, religious and political norms that the nation-state requires to control its citizens, through an emphasis on the connection between its contemporary imposition of various state controls and the nation’s past.

3.2 Heritage as popular culture

Hewison’s position was criticised by a series of commentators. The British Marxist historian Raphael Samuel noted in Theatres of Memory (1994) that the scale of popular interest in the past and the role of that interest in processes of social transformation argued against Hewison’s connection of heritage with Conservative interests. He criticised Hewison’s connection of heritage with Conservative political interests, arguing cogently that heritage and ‘the past’ had been successfully lobbied as a catch-cry for a range of political positions and interests; in particular, heritage had served to make the past more democratic, through an emphasis on the lives of ‘ordinary’ people. He also saw the roots of popular interest in the past as stretching back far earlier than the political era of ‘decline’ suggested by Hewison:

The new version of the national past, notwithstanding the efforts of the National Trust to promote a country-house version of ‘Englishness’, is inconceivably more democratic than earlier ones, offering more points of access to ‘ordinary people’, and a wider form of belonging. Indeed, even in the case of the country house, a new attention is now lavished on life ‘below the stairs’ (the servants’ kitchen) while the owners themselves (or the live-in trustees) are at pains to project themselves as leading private lives – ‘ordinary’ people in ‘family’ occupation. Family history societies, practising do-it-yourself scholarship and filling the record offices and the local history library with searchers, have democratized genealogy, treating apprenticeship indentures as a symbolic equivalent of the coat of arms, baptismal certificates as that of title deeds. They encourage people to look down rather than up in reconstituting their roots, ‘not to establish links with the noble and great’...

Samuel was quick to emphasise heritage not only as a potentially democratic phenomenon, but also to see in the social practices surrounding heritage the possibility for promoting social change. An advocate of the potentially transformative power of history, and of the role of heritage in producing diversity and scaffolding multiculturalism in society, Samuel described heritage as a social process:

Conservation is not an event but a process, the start of a cycle of development rather than (or as well as) an attempt to arrest the march of time. The mere fact of preservation, even if it is intended to do no more than stabilize, necessarily involves a whole series of innovations, if only to arrest the ‘pleasing decay’. What may begin as a rescue operation, designed to preserve the relics of the past, passes by degree into a work of restoration in which a new environment has to be fabricated in order to turn fragments into a meaningful whole.

It is difficult to argue with Samuel’s point about the popular interest in heritage, as it is with the grass-roots involvement of people and communities in appeals to conserve particular forms of heritage. For example, SAVE Britain’s Heritage, an influential campaigning body which works to conserve British architectural heritage, was formed as a direct result of the public reaction to the exhibition The Destruction of the Country House held at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) of decorative arts and design in 1974. However, it is not really enough to say that it was formed in response to ‘public’ outcry – we need to think about who this public is. In this case, it is probably fair to say that the ‘public’ who attended the exhibition at the V&A were well educated, middle-class people with an interest in architecture. But this phenomenon of the movement of heritage into the public sphere as a form of popular entertainment outside of the museum and into public spaces cautions against seeing heritage as entirely something that is imposed ‘from above’.

3.3 Heritage and tourism

John Urry’s (1990) criticisms of Hewison’s The Heritage Industry took another form, providing a useful corrective to the way in which both Wright and Hewison had criticised heritage as ‘false’ history. Focusing particularly on museums, he suggested that tourists are socially differentiated, so an argument that they are lulled into blind consumption by the ‘heritage industry’, as had been suggested by Hewison, could not hold true. Urry drew an analogy with French philosopher Michel Foucault’s concept of ‘the gaze’ to develop the idea of a ‘tourist gaze’. The tourist gaze is a way of perceiving or relating to places which cuts them off from the ‘real world’ and emphasises the exotic aspects of the tourist experience. It is directed by collections of symbols and signs to fall on places that have been previously imagined as pleasurable by the media surrounding the tourist industry. Photographs, films, books and magazines allow the images of tourism and leisure to be constantly produced and reproduced. The history of the development of the tourist gaze shows that it is not ‘natural’ or to be taken for granted, but developed under specific historical circumstances, in particular the exponential growth of personal travel in the second part of the twentieth century. Nonetheless, it owes its roots to earlier configurations of travel and tourism, such as the ‘Grand Tour’ (the standard itinerary of travel undertaken by upper-class Europeans in the period from the late seventeenth century until the mid-nineteenth century which was intended to educate and act as a right of passage for those who took it), and in Britain, the love affair with the British sea-side resort which had its hey-day in the mid-twentieth century.

Tourism and heritage must be seen to be directly related as part of the fundamentally economic aspect of heritage. At various levels, whether state, regional or local, tourism is required to pay for the promotion and maintenance of heritage, while heritage is required to bring in the tourism that buys services and promotes a state’s, region’s or locality’s ‘brand’. Heritage therefore needs tourism, just as it needs political support, and it is this that creates many of the contradictions that have led to the critiques of the heritage industry relating to issues of authenticity, historical accuracy and access.

The connection between heritage and travel might be seen to have a much deeper history. The fifth-century BCE Greek historian Herodotus made a list of the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’, the great monuments of the Mediterranean Rim, which was reproduced in ancient Hellenic guidebooks. Herodotus’ original list was rediscovered during the Middle Ages when similar lists of ‘wonders’ were being produced. What is different about the World Heritage List is that, as a phenomenon of the later part of the twentieth century reflecting the influence of globalisation, migration and transnationalism, it spread a particular, western ‘ideal’ of heritage. This image of heritage, and particularly World Heritage as a canon of heritage places, began to circulate freely and to become widely available for the consumption of people throughout the world. Another important difference is the acceleration in transforming places into heritage – what Hewison and Wright referred to as ‘museumification’ – which involves the almost fetishistic creation of dozens of different lists of types of heritage. Hewison connected this growth in heritage and its commodification with the experience of postmodernity and the constant rate of change in the later part of the twentieth century.

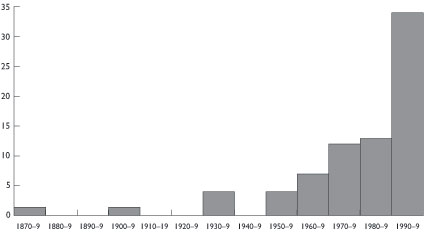

The growth in heritage as an industry can be documented at a broad level by graphing the number of cultural heritage policy documents developed by the major international organisations involved in the management of heritage in the western world. These organisations include the Council of Europe, the International Council of Museums (ICOM), the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), the International Committee on Archaeological Heritage Management (ICAHM, a committee of ICOMOS), the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA), the Organization of World Heritage Cities (OWHC), the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the World Monuments Fund (WMF). The graph of numbers of policy documents over the course of the twentieth century, as the organisations came into being, shows a major period of growth after the 1960s and 1970s (see Figure 3).

A block graph demonstrating the increasing volume of cultural heritage policy documents from the 1870s to the 1990s. One is recorded in the first decade; none in the 1880s and 1890s; one in the first decade of the twentieth century (1900–1909); no more until the 1930s when four policy documents are noted; none in the 1940s; in the fifties a return to the level of the thirties; and a steady rise to 7 in the sixties, 12 in the seventies, 13 in the eighties; then a huge rise to 34 in the nineties.

Urry was interested in explaining the power of the consumer to transform the social role of the museum. He suggested that the consumer has a major role in selecting what ‘works’ and what does not in heritage. It is not possible to set up a museum just anywhere – consumers are interested in authenticity and in other things that dictate their choices, and they are not blindly led by a top–down ‘creation’ of heritage by the state:

Hewison ignores the enormously important popular bases of the conservation movement. For example, like Patrick Wright he sees the National Trust as one gigantic system of outdoor relief for the old upper classes to maintain their stately homes. But this is to ignore the widespread support for such conservation. Indeed Samuel points out that the National Trust with nearly 1.5 million members is the largest mass organisation in Britain ... moreover, much of the early conservation movement was plebeian in character – for example railway preservation, industrial archaeology, steam traction rallies and the like in the 1960s, well before the more obvious indicators of economic decline materialised in Britain.

The outcome of Urry’s discussion of heritage was to shift the balance of the critique of heritage away from whether or not heritage was ‘good’ history to the realisation that heritage was to a large extent co-created by its consumers.

The popular appeal of heritage can be demonstrated by ‘blockbuster’ exhibitions of artefacts and archaeological finds, such as the Treasures of Tutankhamun tour, a worldwide travelling exhibition of artefacts recovered from the tomb of the eighteenth dynasty Egyptian pharaoh which ran from 1972 to 1979. This exhibition was first shown in London at the British Museum in 1972, when it was visited by more than 1.6 million visitors. Over 8 million visited the exhibition in the USA. A follow-up touring exhibition called Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs ran during the period 2005–8. Interestingly, instead of being shown in London at the British Museum, this exhibition was displayed in a commercial entertainment space, the O2 Dome in south-east London, which contains concert venues and cinemas (see Figures 4 and 5). Such an approach to the display of archaeological artefacts shows the way in which the formal presentation of heritage has moved outside the traditional arenas in which it would be presented, to be viewed almost exclusively as a ‘popular’ form of entertainment.

The brightly lit interior of the Tutankhamun Exhibition shop. The sales counter is on the left, while visitors examine displays on the right. Replicas of objects are displayed in glass cases beside the sales point. Less costly items are to the right and against the wall, some (for example an umbrella) only marginally related to the Golden Age of the Pharaohs.

The lofty space within the Dome at the entrance to the Tutankhamun Exhibition. The shop exit occupies the lower third of the image. Above it a huge poster (the width of the shop) displays an image of Tutankhamun’s face and the dates of the exhibition. A glimpse of the structure of the Dome is visible to the right.

Ironically, it was to this same commercialisation of heritage and the past that archaeologist Kevin Walsh (1992) turned in support of the ideas put forward by Hewison in The Heritage Industry. Walsh argued in his book The Representation of the Past that the boom in heritage and museums has led to an increasing commercialisation of heritage which distances people from their own heritage. He suggested that the distancing from economic processes – a symptom of global mass markets that has been occurring since the Enlightenment – has contributed to a loss of ‘sense of place’, and that the heritage industry (and its role in producing forms of desire relating to nostalgia) feeds off this. Loss of a sense of place creates a need to develop and consume heritage products that bridge what people perceive to be an ever increasing gap between past and present. Walsh used an argument similar to one employed by David Lowenthal in The Past is a Foreign Country (1985) and later in The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History (1997). Lowenthal suggested that paradoxically the more people attempt to know the past, the further they distance themselves from it as they replace the reality of the past with an idealised version that looks more like their own reality.

3.4 Heritage is not inherent

I want to return to Smith’s contention that ‘there is no such thing as heritage’. In arguing that there are only opinions and debates about heritage and that heritage is not something that is self-defining, Smith is challenging a model that sees heritage as an intrinsic value of an object, place or practice. An intrinsic value is one that is ‘built-in’ to an object, practice or place; it belongs to the basic and essential features that make something what it is. Under such a model of heritage, heritage objects, places and practices are attributed particular values by the professionals who are involved in assessing and managing heritage, such as architects, archaeologists, anthropologists, engineers and historians. With time, these values become reasonably fixed and unquestioned. This ‘knowledge’, as well as the weight of authority given to heritage professionals, gives the impression that the process of assessing heritage value is simply one of ‘uncovering’ the heritage values that already exist in an object, place or practice. We might think of such a model of heritage as taxonomic: it assumes that there is a pre-existing ordered hierarchy of heritage objects, places and practices in the world.

The idea that heritage is inherent and that its significance is intrinsic to it leads to a focus on the physical fabric of heritage. If value is inherent, it follows that ‘heritage’ must be contained within the physical fabric of a building or object, or in the material things associated with heritage practices.

The implication of this taxonomic viewpoint which holds that heritage is intrinsic to an object, place or practice is that a definitive list of heritage can be created. This idea is closely linked to the idea of an artistic or literary canon as previously discussed. Most practitioners would now recognise that heritage value is not intrinsic; value is something that is attributed to an object, place or practice by particular people at a particular time for particular reasons. Smith is challenging a process that attaches permanent legal conditions to certain places or things. She is arguing that all ‘objects of heritage’ need to be constantly re-evaluated and tested by social practices, needs and desires. Her argument is essentially that heritage is culturally ascribed, rather than intrinsic to things. While this might at first glance appear to be a rather academic point, it is a linchpin of critical heritage studies.

Throughout the second part of the twentieth century the increased recognition of cultural diversity and the contribution of multiculturalism to western societies created a conundrum. How could the old ideas about a fixed canon of heritage, which was established to represent nations with closed borders, come to stand for increasing numbers of diasporic communities of different ethnic origin who were forced, or who elected, to relocate to areas away from their settled territories and who now made such a contribution to the character and make-up of nation-states in western societies? (See, for example, Anderson, 2006.) This challenge, coupled with a recognition that heritage values could not be seen as intrinsic, led to the development of the concept of representativeness, and a shift away from the idea of a single canon of heritage.

Representativeness in heritage recognises that those in positions of power cannot always anticipate the places that the diverse range of members of society will find important. However, through conserving a representative sample of the diverse range of places, objects and practices that could reasonably by called ‘heritage’, we safeguard the protection of a sample of places and things which may be recognised as heritage now or in the future. A representative heritage place or object derives its values from the extent to which it can act as an exemplar of a class of place or type of object. However, it needs to be understood that this was not a total shift in ideals, and that both of these ways of understanding heritage are still taxonomic in nature and still involve the production of lists of heritage.

A more fundamental challenge, which will be taken up in subsequent chapters of this book, is that of non-western cultures which emphasise the intangible aspects of heritage. This has led to a model of managing and assessing values, rather than lists of heritage items. The recognition that it is impossible to conserve an example of every ‘thing’ generates a shift towards a thresholds-based heritage system, where things must be assessed against a series of criteria to qualify for heritage status. The influences of these changing systems of heritage will become clear as you work your way through the chapters of this book.

Before continuing to the next activity

[Searching for informationSAFARI] If you do not feel confident in using the internet to search for information, or you do not know what I mean by the term ‘search engine’, you might find it useful to run through a short exercise to familiarise you with using the internet to search for information. This exercise, Searching for information: Topic 5, World Wide Web, is provided by the OU Library as part of SAFARI (Skills in Accessing, Finding And Reviewing Information).

Once you have finished working through this exercise, return to Activity 4.

Activity 4

Carry out an internet search on the term ‘heritage’ using any internet search engine, then write down the top ten to fifteen search results. Explore a couple of the ‘hits’ by clicking on them and looking at what they contain. On your list, note down whether the hit is a commercial site that is selling something or whether it is more concerned with research or conservation. Record some brief observations about the sort of definition of heritage that your chosen sites employ, or at least about what is implied when you look at them. Why do you think sites like these wish to be associated with ‘heritage’? What sorts of values are being used?

Discussion

Depending on which search engine you used, and where you were searching, you will have come across different search results on the word ‘heritage’. My first three hits were for companies selling bathrooms, needlecraft and real estate. Another hit was for a company selling cars. What do you think this says about heritage? It is obviously a quality that some people feel sells things, such as cars, houses or bathrooms. Evidence that it might be something more comes from exploring some of the internet sites themselves, particularly those that promote museums, historic houses or other ‘official’ heritage places. [English Heritage] Because I am searching in England, one of the top links that came up was for the home page of English Heritage, the government body with legislative responsibility for the protection and promotion of the historic environment in England.

An issue that became clear to me from quickly browsing some of the sites returned by my search was the way in which heritage is linked integrally with travel and tourism. Indeed, World Heritage is very much connected with travel. I know that last time I went on holiday, the first thing I did was search for World Heritage sites in the nearby area, because I am interested in heritage and the past. Although it could be argued that I do this because I have an academic interest, I know I am not alone. Many World Heritage sites are as often featured in tourist brochures as they are in the pages of archaeology journals. Heritage tourism and site visits are seen as an appropriate recreational activity for people in many countries of the world. Many people will first ‘visit’ such places using the internet or through the pages of a guide book before visiting them in person. They might subsequently return to a site using the internet after they have visited it in person. Tourists increasingly migrate back and forth between actual and imagined heritage landscapes, which are mediated through the internet, film and other media.

If you wrote down some observations regarding the values that people seem to associate with heritage, you may have been reminded of Laurajane Smith’s suggestion that many people see the values of heritage as intrinsic to an object, place or practice. To this way of thinking, ‘great’ heritage might be seen to be intrinsically ‘important’, and the values of heritage to people in society as obvious. Using the term ‘heritage’ to describe real estate, for example, might draw on the value that heritage is seen to possess of having ‘stood the test of time’, and of being inherently superior though having done so.

4 What does heritage do?

Heritage and control: the authorised heritage discourse

Anything that an authority (such as the state) designates as worthy of conservation subsequently enters the political arena. Alongside any thought or feeling we might have as individuals about an object, place or practice there will be a powerful and influential set of judgements from this authority which impacts on us. Smith’s argument is that there is a dominant western discourse, or set of ideas about heritage, which she refers to as an authorised (or authorising) heritage discourse, or AHD. We will be returning to the concept of the AHD throughout this book. The AHD is integrally bound up in the creation of lists that represent the canon of heritage. It is a set of ideas that works to normalise a range of assumptions about the nature and meaning of heritage and to privilege particular practices, especially those of heritage professionals and the state. Conversely, the AHD can also be seen to exclude a whole range of popular ideas and practices relating to heritage. Smith draws on case studies from the UK, Australia and the USA to illustrate her arguments. This part of the chapter looks in detail at the concept of the AHD as developed by Smith to illustrate how this particular set of ideas about heritage is made manifest: the ways in which heritage conservation operates at a local or regional level through the documents, protocols, laws and charters that govern the way heritage is assessed, nominated and protected.

Smith suggests that the official representation of heritage has a variety of characteristics that serve to exclude the general public from having a role in heritage and emphasise a view of heritage that can only be engaged with passively. She sees the official discourse of heritage as focused on aesthetically pleasing or monumental things, and therefore focused largely on material objects and places, rather than on practices or the intangible attachments between people and things. She suggests that the documents and charters that govern heritage designate particular professionals as experts and hence as the legitimate spokespeople for the past; they tend to promote the experiences and values of elite social classes, and the idea that heritage is ‘bounded’ and contained within objects and sites that are able to be delineated so that they can be managed.

We can see how these discourses of heritage are made concrete in heritage practice by looking at the International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (1964) (known as the Venice Charter). The Venice Charter, adopted by the Second International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments, meeting in Venice in 1964, was a series of international principles to guide the preservation and restoration of ancient buildings. The philosophy behind the Venice Charter has had a major impact on all subsequent official definitions of heritage and the processes of cultural heritage management.

At the centre of the Venice Charter lie the concept of authenticity and an understanding of the importance of maintaining the historical and physical context of a site or building. The Charter states that monuments are to be conserved not only for their aesthetic values as works of art but also as historical evidence. It sets down the principles of preservation, which relate to the restoration of buildings with work from different periods. In its emphasis on aesthetic values and works of art, it makes implicit reference to the idea of heritage as monumental and grand, as well as to the idea of a canon of heritage.

The Charter begins with these words:

Imbued with a message from the past, the historic monuments of generations of people remain to the present day as living witnesses of their age-old traditions. People are becoming more and more conscious of the unity of human values and regard ancient monuments as a common heritage. The common responsibility to safeguard them for future generations is recognized. It is our duty to hand them on in the full richness of their authenticity.

It is possible to see the lineage of a whole series of concepts about heritage in the Venice Charter. This quote reveals a very important aspect of the AHD involving the abstraction of meaning of objects, places and practices of heritage that come to be seen as representative of something aesthetic or historic in a rather generalised way. The AHD removes heritage objects, places and practices from their historical context and encourages people to view them as symbols – of the national character, of a particular period in history, or of a particular building type. In doing so, they are stripped of their particular meanings and given a series of newly created associations.

The Charter establishes the inherent values of heritage, and the relationship between the value of heritage and its fabric through its emphasis on authenticity. In Article 7 it goes on to reinforce this notion:

ARTICLE 7. A monument is inseparable from the history to which it bears witness and from the setting in which it occurs. The moving of all or part of a monument cannot be allowed except where the safeguarding of that monument demands it or where it is justified by national or international interest of paramount importance.

Ideas about the inherent value of heritage are repeated in Article 15 through the focus on the value of heritage which can be revealed so that its meaning can be ‘read’:

every means must be taken to facilitate the understanding of the monument and to reveal it without ever distorting its meaning.

The Charter is focused almost exclusively on particular kinds of material heritage, namely buildings and monuments, and on the technical aspects of architectural conservation. Once again, we see an emphasis on specialists as the experts in heritage conservation and management:

ARTICLE 2. The conservation and restoration of monuments must have recourse to all the sciences and techniques which can contribute to the study and safeguarding of the architectural heritage.

ARTICLE 9. The process of restoration is a highly specialized operation. Its aim is to preserve and reveal the aesthetic and historic value of the monument and is based on respect for original material and authentic documents. It must stop at the point where conjecture begins, and in this case moreover any extra work which is indispensable must be distinct from the architectural composition and must bear a contemporary stamp. The restoration in any case must be preceded and followed by an archaeological and historical study of the monument.

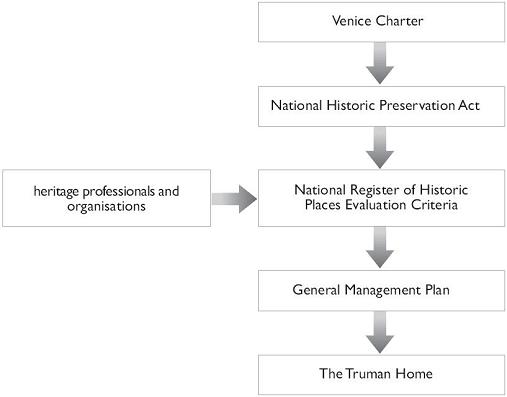

The ideas about heritage that Smith describes using the concept of the AHD circulate not only at the national or global level but filter down to impact on the way in which heritage is managed, presented and understood as a concept at the local level. The next part of the chapter shows how these abstract concepts are made operational in heritage management in North America through the case study of the Harry S. Truman National Historic Site in Missouri.

4.1 Case study: Harry S. Truman National Historic Site, Missouri, USA

Harry S. Truman National Historic Site was gazetted (listed on the register of historic properties) on 23 May 1983 and opened to the public as a house museum on 15 May 1984 after Mrs Bess Truman (nee Wallace) donated the home to the US nation in her will. Bess Truman’s grandfather, George Porterfield Gates, built the fourteen-room, two-and-a-half storey ‘Queen Anne’ style house over the period 1867–95. It was the house in which the thirty-third US president Harry S. Truman lived during the period from his marriage to Bess Wallace on 28 June 1919 until his death on 26 December 1972. The historic site originally included just the ‘Truman Home’, however a series of other properties known as the Truman Farm, the Noland Home and the two Wallace Homes associated with the life of Truman were added to the site in the years that followed (see Figures 6–8).

The heritage values of this site are expressed by the US Department of the Interior National Park Service, the owners and managers of the site, in this way:

The Harry S Truman Historic Site ... contains tangible evidence of his life at home before, during, and after his presidency – places where forces molded and nurtured him.

The significance of Harry S Truman National Historic Site is derived from the time Harry Truman served as the thirty-third president of the United States, from 1945–1953. Yet the park includes physical evidence of a period lasting from 1867 through 1982. This span of time represents nearly the entire context of Harry Truman’s life, and encompasses all major park structures: Truman home, Noland home, Wallace homes and Truman farmhouse ... Most of his ideals concerning religion, social responsibility, financial stability and politics were derived from the people who lived here, as well as from his own experiences in these surroundings. Therefore, the park’s story can be extended backwards to the 1867 date, so long as any interpretation of these times has direct bearing on, and gives the visitor insight into, Harry Truman as president of the United States.

A substantial three-storey clapboard house, irregular in plan, with verandas, a projecting bay on the right, and tall, narrow sash windows. The entrance is under the front veranda up a flight of four broad steps. The house is surrounded by lawns and shrubs, with a lamp-post in the left foreground.

This place might be understood as a class of heritage place known as a ‘house museum’– a site maintained ‘as it was’ to give the public an insight into the life of a person or persons perceived to have been historically important. And, indeed, the statement of significance reproduced in part above certainly makes it clear that the significance of the property lies entirely in its ability to ‘give the visitor insight into Harry Truman as president of the United States’. The statement of significance gives the impression that the significance of the site is embodied within the physical material of the place and its contents: it contains ‘tangible evidence’ of the president and his life, and this material evidence has the ability to provide an insight into his ideas and the events of his presidency. This focus on the tangible and material, along with the rather pleasing setting of the home and its contents, seems consistent with Smith’s contention that the dominant western discourse of heritage is focused on material things rather than intangible practices.

A large, comfortable sitting room with projecting bay windows at the far end, furnished with armchairs, a settee, smaller chairs, occasional tables and a patterned rug. A long-case clock stands in the corner of the room. The furniture is traditional in style with some antique pieces. Lighting is by wall-mounted lights and table lamps.

A two-storey clapboard house of three bays, rectangular in plan, with a veranda shading the front door and two ground-floor windows. Mrs Young is seated in a rocking chair on the grass below the veranda, with her daughter standing on her right and Harry Truman behind her and to her left.

While Truman himself did not belong to the upper classes, he can be seen as belonging to the ‘elite’ classes through his very powerful role as the president of the USA. As you will see from the photographs in Figures 6 and 7, the Truman Home is a rather humble dwelling for a president. Nonetheless, the Truman Home does demonstrate the features that Smith outlines, as even though the structure itself is reasonably humble, it gains its significance through its association with power and celebrity. It derives its status as a heritage site through its association with the ‘biggest and best’–important historical figures and great events. The home and its contents are presented in a manner that is both aesthetically pleasing and familiar to visitors as a ‘house museum’.

Another way in which the Truman Home conforms to Smith’s model is through the notion that there is some inherent virtue to this place that shaped Truman’s character and that can now be ‘read’ by the visitor. The association of the home with a ‘great historical figure’ is consistent with the concept of the AHD. But another key point which emerges from a close reading of the text is that the word ‘associated’ signifies ‘intangible’ heritage. It would be impossible to read this building as Truman’s home without the interpretive texts that tell us about the connection between Truman and the house. So there is a rather subtle interplay between the tangible and intangible aspects of heritage that are displayed in the text. The AHD balances the idea of the inherent significance of the fabric of the building against association, in this case, with Truman as president and what his relatively modest origins mean for current notions of US democracy.

The US Department of the Interior National Park Service General Management Plan (1999) specifies a series of further studies to be carried out to assist with the understanding and management of the Harry S. Truman Historic Site. These include an archaeological overview and assessment, cultural landscape reports, historic resources studies, long-term interpretive plan, and wildlife and vegetation surveys. These reports would be prepared, in this order, by an archaeologist, a cultural geographer or landscape architect, a historian, an interpretation specialist, and a zoologist and botanist. In specifying the form of planning documents required, the management plan establishes the expertise of particular professionals in assessing and documenting the heritage significance of the site. In this way, the general management plan excludes the views of the general public. It gives preference to the work of particular academic disciplines over members of the public or other (non-heritage) specialists who might form an opinion of the significance of the site; and this is despite the fact that the site is being conserved for the general public who ‘need to know as much about their leaders as possible; the type of people we elect to the presidency tells us a great deal about ourselves’ (1999, p. 7). Again, it is possible to see here the exclusion of the general public and the emphasis on heritage as the realm of professionals that Smith suggests are features of the AHD.

These ideas about heritage at the Truman Home do not exist in isolation, but flow down from various other documents which circulate particular ideas about heritage that make up what Smith refers to as the AHD. The National Historic Preservation Act 1966, as amended (NHPA), is the key piece of Federal legislation influencing the way in which heritage is managed and listed in the USA. Although the property was actually listed under the Historic Sites Act 1935, the NHPA is the legislative tool that governs the National Register of Historic Places on which the building sits alongside over 76,000 other heritage places or objects.

The NHPA defines the register as ‘composed of districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects significant in US history, architecture, archaeology, engineering, and culture’ (Section 101 (a) (1) (A)). This definition immediately defines heritage as material, and the value of heritage as inherent in a ‘district, site, building, structure’ or ‘object’. In this sense, the Act can be seen as fulfilling the first of Smith’s characteristics of the AHD, that heritage is seen as contained within material things. The first section of the NHPA, which sets out its purpose, does more to realise many of the official ideas about heritage that Smith describes as comprising the AHD:

- (b)The Congress finds and declares that –