Introduction to bookkeeping and accounting

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 23 April 2024, 3:55 PM

Introduction to bookkeeping and accounting

Introduction

In this free course, Introduction to bookkeeping and accounting, we introduce you to the essential skills and concepts of bookkeeping and accounting. To start with you will gain some practical skills in numeracy including learning about rearranging simple equations as well as some important calculator skills. Afterwards, you will gain knowledge and understanding of the fundamental principles that underpin bookkeeping and accounting. You will learn the time-honoured rules of double-entry bookkeeping and also how to prepare a trial balance and the two principal financial statements: the balance sheet (also known as the statement of financial position) and the profit and loss account (also known as the income statement).

Please note that this is an untutored course and direct feedback on any incorrect answers given in activities is not provided.

Tell us what you think! We’d love to hear from you to help us improve our free learning offering through OpenLearn by filling out this short survey.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of level 1 study in Business & Management.

You might be interested in a more recent Open University course, B124 Fundamentals of accounting

Get careers guidance

This course has been included in the National Careers Service to help you develop new skills.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand and apply the essential numerical skills required for bookkeeping and accounting

understand and explain the relationship between the accounting equation and double-entry bookkeeping

record transactions in the appropriate ledger accounts using the double-entry bookkeeping system

balance off ledger accounts at the end of an accounting period

prepare a trial balance, balance sheet and a profit and loss account.

1 Essential numerical skills required for bookkeeping and accounting

Expertise in mathematics is not required to succeed as a bookkeeper or an accountant. What is needed, however, is the confidence and ability to be able to add, subtract, multiply, divide as well as use decimals, fractions and percentages. Competent bookkeepers and accountants should be able to use mental calculations as well as a calculator to perform these numerical skills. The ability to use a calculator effectively is as important- as the ability to use a spreadsheet program.

The material in this section covers the essential numerical skills of addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, through to decimals, percentages, fractions and negative numbers. You are expected to use a calculator for most of the activities but you are also encouraged to use mental calculations. In the modern world, the assumption is that we use calculators to avoid the tedious process of working out calculations by hand or mentally. The danger, of course, is that you may use a calculator without understanding what an answer means or how it relates to the numbers that have been used. For example, if you calculate that 10% of £90 is £900 (which can easily happen if either you forget to press the per-cent key or it is not pressed hard enough), you should immediately notice that something is very wrong.

Using a calculator requires an understanding of what functions the buttons perform and in which order to carry out the calculations. Your need to study this material is dependent on your mathematical background. If you feel weak or rusty on basic arithmetic or maths, you should find this material helpful. The directions and symbols used will be those found on most standard calculators. (If you find that any of the instructions contained in this material do not produce the answer you expected, please follow the instructions of your calculator.)

There are four basic operations between numbers, each of which has its own notation:

- Addition 7 + 34 = 41

- Subtraction 34 – 7 = 27

- Multiplication 21 x 3 = 63, or 21 * 3 = 63

- Division 21 ÷ 3 = 7, or 21 / 3 = 7

The next section will examine the application of these operations and the correct presentation of the results arising from them.

1.1 Use of BODMAS and brackets

When several operations are combined, the order in which they are performed is important. For example, 12 + 21 x 3 might be interpreted in two different ways:

Activity 1

(a) add 12 to 21 and then multiply the result by 3

Answer

The first way gives a result of 99.

(b) multiply 21 by 3 and then add the result to 12

Answer

and the second a result of 75.

Discussion

We need some way of ensuring that only one possible interpretation can be placed upon the formula presented. For this we use BODMAS. BODMAS give us the correct sequence of operations to follow so that we always get the right answer:

- (B)rackets

- (O)rder

- (D)ivision

- (M)ultiplication

- (A)ddition

- (S)ubtraction

According to BODMAS, multiplication should always be done before addition, therefore 75 is actually the correct answer according to BODMAS.

(‘Order’ may be an unfamiliar term to you in this context but it is merely an alternative for the more common term, ‘power’ which means a number is multiplied by itself one or more times. The ‘power’ of one means that a number is multiplied by itself once, i.e., 2 x 1, 3 x 1, etc., the ‘power’ of two means that a number is multiplied by itself twice, i.e., 2 x 2, 3 x 3, etc. In mathematics, however, instead of writing 3 x 3 we write 3 2 and express this as three to the ‘power’ or ‘order’ of 2.)

Brackets are the first term used in BODMAS and should always be used to avoid any possibility of ambiguity or misunderstanding. A better way of writing 12 + 21 x 3 is thus 12 + (21 x 3). This makes it clear which operation should be done first.

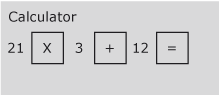

12 + (21 x 3) is thus done on the calculator by keying in 21 x 3 first in the sequence:

Activity 2

Complete the following calculations.:

Part (a)

(a) (13 x 3) + 17

Answer

(a) 56

Part (b)

(b) (15 / 5) – 2

Answer

(b) 1

Part (c)

(c) (12 x 3) /2

Answer

(c) 18

Part (d)

(d) 17 – (3 x (2 + 3))

Answer

(d) 2 (Hint: did you enter the expression in the inner brackets i.e. (2 +3) first?)

Part (e)

(e) ((13 + 2) / 3) –4

Answer

(e) 1

Part (f)

(f) 13 x (3 + 17)

Answer

(f) 260

1.2 Use of calculator memory

A portable calculator is an extremely useful tool for a bookkeeper or an accountant. Although PCs normally have electronic calculators, there is no substitute for the convenience of a small, portable calculator or its equivalent in a mobile phone or personal organiser.

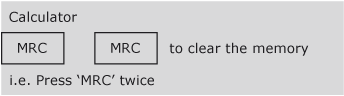

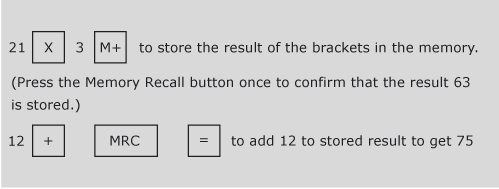

When using the calculator, it is safer to use the calculator memory (M+ on most calculators) whenever possible, especially if you need to do more than one calculation in brackets. The memory calculation will save the results of any bracket calculation and then allow that value to be recalled at the appropriate time. It is always good practice to clear the memory before starting any new calculations involving its use. You do so by pressing the MRC key, representing Memory Recall or its equivalent, twice. (Note: this key is often labelled R.MC or R.CM. The first time the key is pressed memory is recalled and the second time it is cleared. If in doubt about your calculator, consult its manual.)

Taking the previous example we can recalculate it using the memory function.

12 + (21 x 3) = 75

Activity 3

Use the memory on your calculator to calculate each of the following:

Part (a)

(a) 6 + (7 – 3)

Answer

(a) 10

Part (b)

(b) 14.7 / (0.3 + 4.6)

Answer

(b) 3

Part (c)

(c) 7 + (2 x 6)

Answer

(c) 19

Part (d)

(d) 0.12 + (0.001 x 14.6)

Answer

(d) 0.1346

1.3 Rounding

For most business and commercial purposes the degree of precision necessary when calculating is quite limited. While engineering can require accuracy to thousandths of a centimetre, for most other purposes tenths will do. When dealing with cash, the minimum legal tender in the UK is one penny, or £00.01, so unless there is a very special reason for doing otherwise, it is sufficient to calculate pounds to the second decimal place only.

However, if we use the calculator to divide £10 by 3, we obtain £3.3333333. Because it is usually only the first two decimal places we are concerned about, we forget the rest and write the result to the nearest penny of £3.33.

This is a typical example of rounding, where we only look at the parts of the calculation significant for the purposes in hand.

Consider the following examples of rounding to two decimal places:

- 1.344 rounds to 1.34

- 2.546 rounds to 2.55

- 3.208 rounds to 3.21

- 4.722 rounds to 4.72

- 5.5555 rounds to 5.56

- 6.9966 rounds to 7.00

- 7.7754 rounds to 7.78

Rule of rounding

If the digit to round is below 5, round down. If the digit to round is 5 or above, round up.

Activity 4

Round the following numbers to two decimal places:

Part (a)

(a) 0.5678

Answer

(a) 0.57

Part (b)

(b) 3.9953

Answer

(b) 4.00

Part (c)

(c) 107.356427

Answer

(c) 107.36

Activity 5

Round the same numbers as above to three decimal places:

Part (a)

(a) 0.5678

Answer

(a) 0.568

Part (b)

(b) 3.9953

Answer

(b) 3.995

Part (c)

(c) 107.356427

Answer

(c) 107.356

1.4 Fractions

So far we have thought of numbers in terms of their decimal form, e.g., 4.567, but this is not the only way of thinking of, or representing, numbers. A fraction represents a part of something. If you decide to share out something equally between two people, then each receives a half of the total and this is represented by the symbol ½.

A fraction is just the ratio of two numbers: 1/2, 3/5, 12/8, etc. We get the corresponding decimal form 0.5, 0.6, 1.5 respectively by performing division. The top half of a fraction is called the numerator and the bottom half the denominator, i.e., in 4/16, 4 is the numerator and 16 is the denominator. We divide the numerator (the top figure) by the denominator (the bottom figure) to get the decimal form. If, for instance, you use your calculator to divide 4 by 16 you will get 0.25.

A fraction can have many different representations. For example, 4/16, 2/8, and 1/4 all represent the same fraction, one quarter or 0.25. It is customary to write a fraction in the lowest possible terms. That is, to reduce the numerator and denominator as far as possible so that, for example, one quarter is shown as 1/4 rather than 2/8 or 4/16.

If we have a fraction such as 26/39 we need to recognise that the fraction can be reduced by dividing both the denominator and the numerator by the largest number that goes into both exactly. In 26/39 this number is 13 so (26/13) / (39/13) equates to 2/3.

We can perform the basic numerical operations on fractions directly. For example, if we wish to multiply 3/4 by 2/9 then what we are trying to do is to take 3/4 of 2/9, so we form the new fraction: 3/4 x 2/9 = (3 x 2) / (4 x 9) = 6/36 or 1/6 in its simplest form.

In general, we multiply two fractions by forming a new fraction where the new numerator is the result of multiplying together the two numerators, and the new denominator is the result of multiplying together the two denominators.

Addition of fractions is more complicated than multiplication. This can be seen if we try to calculate the sum of 3/5 plus 2/7. The first step is to represent each fraction as the ratio of a pair of numbers with the same denominator. For this example, we multiply the top and bottom of 3/5 by 7, and the top and bottom of 2/7 by 5. The fractions now look like 21/35 and 10/35 and both have the same denominator, which is 35. In this new form we just add the two numerators.

(3/5) + (2/7) = (21/35) + (10/35)

= (21 + 10) / 35

= 31/35

Activity 6

Part (a - i)

(a) Convert the following fractions to decimal form (rounded to three decimal places) by dividing the numerator by the denominator on your calculator:

(i) 125/1000

Answer

(i) 0.125

Part (a - ii)

(ii) 8/24

Answer

(ii) 0.333

Part (a - iii)

(iii) 32/36

Answer

(iii) 0.889

Part (b - i)

(b) Perform the following operations between the fractions given:

(i) 1/2 x 2/3

Answer

(i) 1/3

Part (b - ii)

(ii) 11/34 x 17/19

Answer

(ii) 187/646 = 11/38 (if top and bottom both divided by 17)

Part (b - iii)

(iii) 2/5 x 7/11

Answer

(iii) 14/55

Part (b - iv)

(iv) 1/2 + 2/3

Answer

(iv) 7/6 or 1 1/6

Part (b - v)

(v) 3/4 x 4/5

Answer

(v) 12/20 simplified to 3/5

1.5 Ratios

Ratios give exactly the same information as fractions. Accountants make extensive use of ratios in assessing the financial performance of an organisation.

A supervisor’s time is spent in the ratio of 3:1 (pronounced ‘three to one’) between Departments A and B. (This may also be described as being ‘in the proportion of 3 to 1.’) Her time is therefore divided 3 parts in Department A and 1 part in Department B.

There are 4 parts altogether and:

- 3/4 time is in Department A

- 1/4 time is in Department B

If her annual salary is £24,000 then this could be divided between the two departments as follows:

- Department A 3/4 x £24,000 = £18,000

- Department B 1/4 x £24,000 = £6,000

Activity 7

A company has three departments who use the canteen. Running the canteen costs £45,000 per year and these costs need to be shared out among the three departments on the basis of the number of employees in each department.

| Department | Number of employees |

|---|---|

| Production | 125 |

| Assembly | 50 |

| Distribution | 25 |

How much should each department be charged for using the canteen?

Answer

Production

(125 / (125 + 50 + 25) x £45,000 = £28,125)

Assembly

(50 / (125 + 50 + 25) x £45,000 = £11,250)

Distribution

(25 / (125 + 50 + 25) x £45,000 = £5,625)

1.6 Percentages

Percentages also indicate proportions. They can be expressed either as fractions or as decimals:

45% = 45/100 = 0.45

7% = 7/100 = 0.07

Their unique feature is that they always relate to a denominator of 100. Percentage means simply ‘out of 100’ so 45% is ‘45 out of 100’, 7% is ‘7 out of 100’, etc.

A company is offered a loan to a maximum of 80% of the value of its premises. If the premises are valued at £120,000 then the company can borrow the following:

£120,000 x 80% = £120,000 x 0.80 = £96,000

Fractions and decimals can also be converted to percentages. To change a decimal to a percentage you need to multiply by 100:

0.8 = 80%

0.75 = 75%

To change a percentage to a decimal you need to divide by 100:

60% = 0.6

3% = 0.03

To convert a fraction to a percentage it is necessary to first change the fraction to a decimal:

4/5 = 0.8 = 80%

3/4 = 0.75 = 75%

If a machine is sold for £120 plus VAT (Value Added Tax – a sales tax in the UK) at 17.5% then the actual cost to the customer is:

£120 + (17.5% of 120) = £120 + (0.175 x 120) = £141

Alternatively, the amount can be calculated as:

£120 x (100% + 17.5%) = £120 x (1.00 + 0.175) = £120 x 1.175 = £141

If the machine were quoted at the price that included VAT (the gross price), and we wanted to calculate the price before VAT, then we would need to divide the amount by (100% + 17.5%) = 117.5% or 1.175. The gross price of £141 divided by 1.175 would thus give the net price of £120. This principle can be applied to any amount which has a percentage added to it.

For example, a restaurant bill is a total of £50.40 including a 12% service charge. The bill before the service charge was added would be:

£50.40 / 1.12 = £45.00

Activity 8

Part (a - i)

(a) Convert the following to percentages

Part (a - i)

(i) 0.9

Answer

(i) 90%

Part (a - ii)

(ii) 1.2

Answer

(ii) 120%

Part (a - iii)

(iii) 1/3

Answer

(iii) 33.33%

Part (a - iv)

(iv) 0.03

Answer

(iv) 3%

Part (a - v)

(v) 1/10

Answer

(v) 10%

Part (a - vi)

(vi) 1 1/4

Answer

(vi) 125%

(b) A company sells its product for £65 per unit. How much will it sell for if the customer negotiates a 20% discount?

Answer

£65 x (1 – 0.2) = £52

(c) If a second product is sold for £65.80 including 17.5% value added tax, what is the net price before tax?

Answer

£65.8 / 1.175 = £56

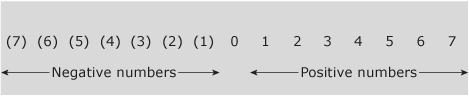

1.7 Negative numbers and the use of brackets

Numbers smaller than zero (shown to the left of zero on the number line in the figure below) are called negative numbers. We indicate they are negative by putting them in brackets as shown in the figure below.

Rules of negative numbers

The rules for using negative numbers can be summarised as follows:

Addition and subtraction

- Adding a negative number is the same as subtracting a positive 50 + (-30) = 50 – 30 = 20

- Subtracting a negative number is the same as adding a positive 50 – (-30) = 50 + 30 = 80

Multiplication and division

- A positive number multiplied by a negative gives a negative 20 x -4 = -80

- A positive number divided by a negative gives a negative 20 / -4 = -5

- A negative number multiplied by a negative gives a positive -20 x -4 = 80

- A negative number divided by a negative gives a positive -20 / -4 = 5

Try to confirm the above rules for yourself by carrying out the following exercise either manually or by means of a calculator.

Activity 9

Calculate each of the following. (In this activity we will assume the convention that if a number is in brackets it means it is negative).

Part (a)

(a) (2) x (3)

Answer

(a) 6

Part (b)

(b) 6 – (8)

Answer

(b) 14

Part (c)

(c) 6 + (8)

Answer

(c) (2)

Part (d)

(d) 2 x (3)

Answer

(d) (6)

Part (e)

(e) (8) / 4

Answer

(e) (2)

Part (f)

(f) (8) / (4)

Answer

(f) 2

Important note

Always remember that while a single number in brackets means that it is negative, the rule of BODMAS means that brackets around an ‘operation’ between two numbers, positive or negative, means that this is the first operation that should be done. The answer for a series of operations in an example such as 12 + (-8 – 2).would thus be 2 according to the rules of BODMAS and negative numbers. Note: if 12 + (-8 – 2) was given as 12 + ((8) – 2) the answer would still be 2 as (8) is just another way of showing -8.

1.8 The test of reasonableness

Applying a test of reasonableness to an answer means making sure the answer makes sense. This is especially important when using a calculator as it is surprisingly easy to press the wrong key.

An example of a test of reasonableness is if you use a calculator to add 36 to 44 and arrive at 110 as an answer. You should know immediately that there is a mistake somewhere as two numbers under 50 can never total more than 100.

When using a calculator it is always a good idea to perform a quick estimate of the answer you expect. One way of doing this is to round off numbers. For instance if you are adding 1,873 to 3,982 you could round these numbers to 2,000 and 4,000 so the answer you should expect from your calculator should be in the region of 6,000.

Test your ability to perform the test of reasonableness by completing the following short multiple choice quiz. Do not calculate the answer, either mentally or by using an electronic calculator, but try to develop a rough estimate for what the answer should be. Then determine from the choices presented to you which makes the most sense, i.e., the choices that are most reasonable.

Activity 10

Choose the correct answer purely on what appears to be most reasonable.

| (1) 126 / 7= | (2) 17 x 26 = | (3) 6,460 / 760 = |

|---|---|---|

| a. 180 | a. 44.2 | a. 850 |

| b. 0.18 | b. 442 | b. 0.85 |

| c. 18 | c. 4,420 | c. 8.5 |

| d. 1.8 | d. 44,420 | d. 85 |

| (4) 330 x 8.4= | (5) 269 + 378= | (6) 562 – 268 = |

| a. 277.2 | a. 547 | a. 194 |

| b. 2,772 | b. 747 | b. 294 |

| c. 27,772 | c. 647 | c. 394 |

Answer

(1) c. 18

(2) b. 442

(3) c. 8.5

(4) b. 2,772

(5) c. 647

(6) b. 294

1.9 Table of equivalencies

The next activity in developing your numerical skills required for bookkeeping and accounting is to give you practice in converting between percentages, decimals and fractions. It is a very useful numerical skill to be able to know or to work out quickly the equivalent between a number given in percentage form and in other forms.

Activity 11

Use the box below to record your answers for the gaps in the table. The first one is done for you. Answers required in decimals should be rounded off to two decimal points. Answers required in fractions should be written in the lowest possible terms.

| Percentage | Decimal | Fraction |

|---|---|---|

| 1% | 0.01 | 1/100 |

| 2% |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

0.05 |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

1/10 |

| 20% |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

0.25 |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

| 33 1/3% |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

0.5 |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

2/3 |

| 75% |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

1.0 |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

2/1 |

Answer

| Percentage | Decimal | Fraction |

|---|---|---|

| 1% | 0.01 | 1/100 |

| 2% | 0.02 | 1/50 |

| 5% | 0.05 | 1/20 |

| 10% | 0.1 | 1/10 |

| 20% | 0.2 | 1/5 |

| 25% | 0.25 | 1/4 |

| 33 1/3% | 0.33 | 1/3 |

| 50% | 0.5 | 1/2 |

| 66 2/3% | 0.67 | 2/3 |

| 75% | 0.75 | 3/4 |

| 100% | 1.0 | 1/1 |

| 200% | 2.0 | 2/1 |

1.10 Manipulation of equations and formulae

The final activity in developing your numerical skills is to revise the manipulation of simple equations.

Being able to understand and express the Accounting Equation in different forms is crucial to understanding a fundamental accounting concept (the dual aspect concept) and the principal financial statements (the profit and loss account and the balance sheet). You will learn more about the Accounting Equation in sections 2 and 3.

An equation is a mathematical expression which shows the relationship between numbers through the use of the equal sign. An example of a simple equation might be 2 + 3 = 5.

A special type of equation is an algebraic equation where a letter, say ‘x’, represents a number, i.e. in x + 2 = 5, ‘x’ represents 3 in order to make the equation true.

Algebraic equations are solved by manipulating the equation so that the letter stands on its own. This is achieved in the equation x + 2 = 5 by the following two steps.

- x = 5 – 2

- x = 3

The principal rule of manipulating equations is whatever is done to one side of the equal side must also be done to the other, as was shown above.

x = 5 – 2 is achieved by subtracting 2 from both sides of the equation x + 2 = 5, i.e.:

- x + 2 – 2 = 5 – 2

- x = 5 – 2

Manipulating an equation to get the algebraic letter to stand on its own involves ‘undoing’ the equation by using the inverse or opposite of the original operation. In the example of x + 2 = 5, the operation of adding 2 must be undone by subtracting 2 from either side of the equal sign.

The following table shows a number of examples of how equations are manipulated to obtain the correct number for the algebraic letter.

| Operation | Inverse | Equation |

|---|---|---|

| add 7 | subtract 7 | a + 7 = 9 |

| a + 7 – 7 = 9 – 7 | ||

| a = 2 | ||

| subtract 5 | add 5 | b – 5 = 6 |

| b – 5 + 5 = 6 + 5 | ||

| b = 11 | ||

| multiply by 3 | divide by 3 (or multiply by 1/3) | c x 3 = 18 |

| c x 3 / 3 = 18 / 3 | ||

| c = 6 | ||

| divide by 6 | multiply by 6 | d / 6 = 2 |

| d / 6 x 6 = 2 x 6 | ||

| d = 12 |

An equation such as a x 3 = 12 can also be expressed as a3 = 12 or 3a = 12, i.e., if an algebraic letter is placed directly next to a number in an equation it means that the letter is to be multiplied by the number.

The correct number for the algebraic letter ‘a’ in the equation 3a = 12 will be obtained thus:

- 3a = 12

- 3a / 3 = 12 / 3

- a = 4

Manipulating or rearranging formulae involves the same process as manipulating or rearranging equations.

Important note

A formula is simply an equation that states a fact or rule such as S = D / T or Speed is equal to Distance divided by Time.

In the formula S = D / T, S is the subject of the formula. (This simply means that S stands on its own and is determined by the other parts of the formula. By convention the subject is always placed on the left-hand side of the equal sign, although S = D / T means the same as D / T = S)

As we learnt to rearrange or manipulate an equation, the formula S = D / T can also be manipulated to make D or T the subject.

S = D / T

D / T = S (turning the formula around)

D = S x T (multiplying both sides of the formula by T)

Or, from D = S x T

D / S = T (dividing both sides of the formula by S)

T = D / S (turning the formula around)

Activity 12

Solve the following algebraic equations below.

Part (i)

(i) c + 9 = 11

Answer

(i) c =2

Part (ii)

(ii) a – 15 = 21

Answer

(ii) a = 36

Part (iii)

(iii) d x 7 = 63

Answer

(iii) d =9

Part (iv)

(iv) b / 13 = 13

Answer

(iv) b = 169

Activity 13

Rearrange the formula h = 3dy – r to make:

Part (i)

(i) r the subject

Answer

(i) h = 3dy – r

h + r = 3dy

r = 3dy – h

Part (ii)

(ii) y the subject

Answer

(ii) h = 3dy – r

h + r = 3dy

3dy = h + r

y = (h + r) / 3d (Hint: did you remember to use brackets?)

2 Double entry and the balance sheet

Section learning outcomes

By the end of this section you should be able to:

- understand and explain the need for financial records and financial statements

- understand the business entity and the dual aspect concepts

- define assets, liabilities and capital

- understand and explain the relationship between the accounting equation and double-entry bookkeeping

- record transactions in the appropriate ledger accounts using the double-entry bookkeeping system

- understand a simple balance sheet in a vertical format

- balance off accounts at the end of an accounting period

- prepare a trial balance.

2.1 Accounting records and financial statements

Accounting records store information about all the financial transactions and events of a business. A small business may only have a few financial transactions a day to record while a large, multinational business may have many thousands.

Information point

This course focuses on business organisations but the core concepts and principles of bookkeeping also apply to non-profit organisations.

Why do all businesses need to keep accounting records?

- They keep track of where money comes from and how it is spent.

- They are required by law.

- They help to keep control of goods and property owned by a business.

- They are used as the basis for financial statements.

What are financial statements?

Financial statements are summaries of accounting records that are drawn up to satisfy the information needs of owners and other stakeholders in the business. These stakeholders are presented with the financial records in the form of two main financial summaries or statements. The first of these is a balance sheet which shows the financial state of affairs of a business at a specific date; the second is a profit and loss account which records the income and expenditure of a business for a period of time.

Who are the typical stakeholders of a business and what information do they need?

| Stakeholders | Information needs |

|---|---|

| Owners | Owners, whether they own all or part of a business, want information on the risk and return of their investment in a business. |

| Managers | Managers need to have reliable financial information on which to base their decisions. |

| Lenders | Lenders and potential lenders need to have information about the ability of the firm to repay loans and to pay interest. |

| Suppliers | Suppliers, if they give credit to the business, want to know if they will be paid. |

| Employees | Employees are particularly interested in the ability of the firm to pay wages and pensions. |

| Customers | Customers, especially if they are dependent on a supplier, need to know if the business will continue to exist. |

| Governments and their agencies | Reliable financial information from businesses is used as the basis for taxation. In some countries it is also used to compile information about the economy. |

| The public | Financial statements often include information relevant to the public interest, such as environmental information or policies on employment of disabled people, etc. |

The biggest businesses have the most stakeholders. Whatever the size of the business, active and responsible stakeholders will always be interested in how a business, in which they have an informed interest, is financed, and how this finance is used to run the business.

2.2 Accounting records and the business entity concept

The accounting records for even the simplest business must be kept separate from the personal affairs of the owner or owners. This concept that the business stands apart from the owners is known as the business entity concept.

What is the simplest type of business entity?

The simplest type of business is known as a sole trader or a sole proprietor. It is a business that is owned and controlled by one person, although the business may employ other people. Sole traders normally adopt a trading name, but the business has no separate legal existence from the owner. As a result, the sole trader (i.e. the owner), although entitled to receive all of the profit or net income of the firm, is also personally liable for the debts of the business. This is referred to as unlimited liability. For bookkeeping and accounting purposes, however, the sole trader will run his or her business as a separate entity following the ‘business entity concept’.

2.3 Definitions of assets, capital and liabilities

A business when it starts has no money. The owner puts money in (known as owner’s capital) and perhaps borrows money as well, and this money is used to buy assets that are expected to bring financial benefits for the business in the future. If it were a retail business, these assets might be premises, equipment and goods for resale. A service business might only need an office, furniture and computers.

The accounting records separate out the finance put into the company by the owner (owner’s capital) and the finance borrowed (a liability or debt that needs to be repaid). The accounting records also separate out the assets bought from the finance used to buy the assets. The firm can only have as many assets as it has finance available. The accounting records consequently will always reflect that:

Assets = finance put into the business either from the owner or borrowed

or

Assets = capital + liabilities (i.e. finance from the owner/s + finance borrowed)

2.3.1 What are assets, capital and liabilities?

Assets are the economic resources belonging to a business. Assets could be money in a cash register or bank account, or items such as property, fixtures and furniture, equipment, motor vehicles, and stock or goods for resale. An important asset in businesses which sell goods or services on credit is money owed to the enterprise by customers. This asset is known as debtors.

Capital is the value of the investment in the business by the owner(s). It is that part of the business that belongs to the owner; hence it is often described as the owner’s interest.

Liabilities are the debts owed by the firm. The main types of liabilities are creditors (money owed by the business to suppliers of goods and services), bank overdrafts and bank loans.

Activity 14

A business at the end of its first year of trading has assets of £10,000 and liabilities of £8,000. What important information is contained in the difference between these two figures?

Answer

Assets of £10,000 less liabilities of £8,000 mean that the business has positive or net assets of £2,000. Another way of saying that the business has net assets of £2,000 is that the business has a net value of £2,000 belonging to the owners. (As defined above, this is the owner’s interest or capital.) Whatever the size and nature of a business, the assets minus the liabilities of the business will always equal the capital belonging to the owners.

What is the importance of knowing that, for all businesses, Assets – Liabilities = Capital?

Answer

This equation for the owner’s interest or capital (Assets – Liabilities = Capital) is known as the accounting equation. In the UK it is also known as the balance sheet equation because it reflects the format followed by accountants in the UK when preparing the financial summary of assets, liabilities and capital, which is known as a balance sheet.

Activity 15

Edgar Edwards sets up a small sole trader business as Edgar Edwards Enterprises on 1 July in the year 20X2. Complete the table below, in which the first six transactions of the business are listed in the left-most column.

Information point

The effect of each of the first three transactions, as well as the overall effect of all six transactions, has been completed for you to show you the following important aspects of the accounting equation:

- i.Each transaction will have a positive (plus) and/or a negative (minus) effect on the assets or liabilities concerned.

- ii.Assets or liabilities should be further broken down into the type of asset or liability.

- iii.For each transaction, as well as for the overall effect of a number of transactions, the figure for capital will reflect the accounting equation: A – L=C.

| Assets £ | - Liabilities £ | = Capital £ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The owner starts the business with £5,000 paid into a business bank account on 1 July 20X2. | +5,000 (bank) |

0 |

+5,000 |

| 2. The business buys furniture for £400 on credit from Pearl Ltd on 2 July 20X2. | +400 (furniture) |

+400 (creditor: Pearl Ltd) |

0 |

| 3. The business buys a computer with a cheque for £600 on 3 July 20X2. | +600 (computer) –600 (bank) |

0 |

0 |

| 4. The business borrows £5,000 on loan from a bank on 4July 20X2. The money is paid into the business bank account. | |||

| 5. The business pays Pearl Ltd £200 by cheque on 5 July 20X2. | |||

| 6. The owner takes £50 from the bank for personal spending on 6 July 20X2. | |||

| Summary (overall effect) | Total +10,150 | Total +5,200 | Total +4,950 |

Answer

| Assets £ | - Liabilities £ | = Capital £ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The owner starts the business with £5,000 paid into a business bank account on 1 July 20X2. | +5,000 (bank) | 0 | +5,000 |

| 2. The business buys furniture for £400 on credit from Pearl Ltd on 2 July 20X2. | +400 (furniture) | +400 (creditor: Pearl Ltd) | 0 |

| 3. The business buys a computer with a cheque for £600 on 3 July 20X2. | +600 (computer) –600 (bank) |

0 | 0 |

| 4. The business borrows £5,000 on loan from a bank on 4July 20X2. The money is paid into the business bank account. | +5,000 (bank) | +5,000 (loan) | 0 |

| 5. The business pays Pearl Ltd £200 by cheque on 5 July 20X2. | –200 (bank) | –200 (creditor: Pearl Ltd) | 0 |

| 6. The owner takes £50 from the bank for personal spending on 6 July 20X2. | –50 (bank) | 0 | –50 |

| Summary (overall effect) | Total +10,150 | Total +5,200 | Total +4,950 |

How does the summary or overall change in the table above relate to the accounting equation?

Applying the accounting equation, A – L = C, we see that the overall change in assets in the period (+£10,150) less the change in liabilities in the period (+£5,200) is equal to the change in capital in the period (+£4,950).

What is noticeable about the accounting equation after every transaction in the table above?

The accounting equation remains in balance as every transaction must alter both sides of the equation, A– L= C, by the same amount. This can be shown by looking at the six transactions above as follows:

- £400 – £400 = £0 (both sides of the equation increase by £0)

- (£600 – £600) – £0 = £0 (both sides of the equation increase by £0)

- £5,000 – £5,000 = £0 (both sides of the equation increase by £0)

- –£200 – (–£200) = £0 (both sides of the equation increase by £0)

- –£200 – (–£200) = £0 (both sides of the equation increase by £0)

Every transaction above is thus recorded twice in order to keep the accounting equation in balance. This dual effect is known as the dual aspect concept and is the basic principle associated with both the double-entry bookkeeping system and the production of the balance sheet. We will look at the double-entry bookkeeping system in more detail later in this section, but will look more closely at the balance sheet in '2.4 A simplified UK balance sheet formula'.

What then is the dual aspect concept and how does it relate to the accounting equation?

The dual aspect concept is that every transaction has two aspects which must be equal in order to keep in balance the accounting equation, A – L= C.

2.4 A simplified UK balance sheet format

How do businesses in the UK most commonly present information in the balance sheet?

In the UK, balance sheets are commonly prepared in a vertical format of the accounting equation. This gives the owners clear information about the net assets of the enterprise, which always equals their capital or owner ’s interest in the enterprise. The balance sheet is normally produced at the end of each trading or financial year and is a snapshot of the financial position of the business on the last day of the financial year. For learning purposes we will compile a UK balance sheet for Edgar Edwards Enterprises above at the end of its sixth day of trading.

A simple vertical balance sheet format could look like this:

| Assets | £ |

|---|---|

| Furniture | 400 |

| Computer | 600 |

| Bank (£5,000–£600+£5,000–£200–£50) | 9,150 |

| Total assets (A) | 10,150 |

| Liabilities | |

| Bank loan | 5,000 |

| Creditors (£400-£200) | 200 |

| Total liabilities (L) | 5,200 |

| Net assets (A - L) | Total 4,950 |

| Capital (C) | Total 4,950 |

Activity 16

Fill in the missing values in Table 10 in order to prepare a new balance sheet after each of the six transactions by Edgar Edwards Enterprises we have seen in Section 2.3. (The first and last columns have been done for you.). You may find it easier to work on a piece of paper before inputting your answers into the box.

| 1 July 20X2 | 2 July 20X2 | 3 July 20X2 | 4 July 20X2 | 5 July 20X2 | 6 July 20X2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| £ | £ | £ | £ | £ | £ | |

| Assets | ||||||

| Furniture | 0 |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

400 |

| Computer | 0 |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

600 |

| Bank | 5,000 |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

9,150 |

| Total Assets (A) | 5,000 |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

10,150 |

| Liabilities | ||||||

| Bank loan | 0 |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

5,000 |

| Creditors | 0 |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

200 |

| Total liabilities (L) | 0 |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

5,200 |

| Net Assets (A-L) | Total 5,000 |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

Total 4,950 |

| Capital (C) | Total 5,000 |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

Total 4,950 |

Answer

| 1 July 20X2 | 2 July 20X2 | 3 July 20X2 | 4 July 20X2 | 5 July 20X2 | 6 July 20X2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| £ | £ | £ | £ | £ | £ | |

| Assets | ||||||

| Furniture | 0 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 |

| Computer | 0 | 0 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 |

| Bank | 5,000 | 5,000 | 4,400 | 9,400 | 9,200 | 9,150 |

| Total Assets (A) | 5,000 | 5,400 | 5,400 | 10,400 | 10,200 | 10,150 |

| Liabilities | ||||||

| Bank loan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5,000 | 5,000 | 5,000 |

| Creditors | 0 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 200 | 200 |

| Total liabilities (L) | 0 | 400 | 400 | 5,400 | 5,200 | 5,200 |

| Net Assets (A-L) | Total 5,000 | Total 5,000 | Total 5,000 | Total 5,000 | Total 5,000 | Total 4,950 |

| Capital (C) | Total 5,000 | Total 5,000 | Total 5,000 | Total 5,000 | Total 5,000 | Total 4,950 |

It can be clearly seen in the six balance sheets above that each new financial transaction leads to new figures in the accounting equation A – L =C and thus a new balance sheet. Normally, however, it is not seen as useful information to have a new balance sheet after each transaction. Rather, an ongoing record or account is kept of each sub-heading or sub-category in the balance sheet (Furniture, Computer, Bank, Bank loan, etc.) and at the end of the financial period the final figures or balances for all the individual sub-categories are put together to produce an end-of-period balance sheet.

These sub-categories in the balance sheet correspond to the accounts in a book called the nominal ledger or general ledger or ledger for short. (Ledger is an old word that means book.) There would thus be a ledger account called ‘Bank’, for example, which records every financial transaction affecting the bank. After each relevant transaction involving the bank account, the net figure or balance in the bank account would either go up or down.

Information point

With the advent of computerised accounting, a new balance sheet, reflecting the new figures in the accounting equation, can automatically be generated after each business transaction. Businesses, however, only publish the balance sheet at the end of a financial period, normally a year, as it is this balance sheet that is required by law and other forms of regulation.

2.5 T-accounts, debits and credits

What do all accounts look like in a double-entry system?

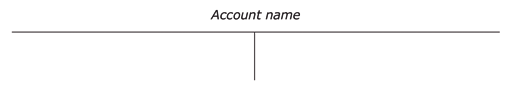

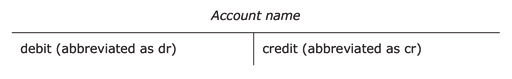

Traditional double-entry bookkeeping divides every account into two halves as follows:

This T appearance has led to the convention of ledger accounts being referred to as T-accounts.

Convention, which has not changed for hundreds of years, prescribes that the left-hand side of a T-account is called the debit side, and the right-hand side is called the credit side.

What is the main reason that all accounts are divided into a left or debit side and a right or credit side?

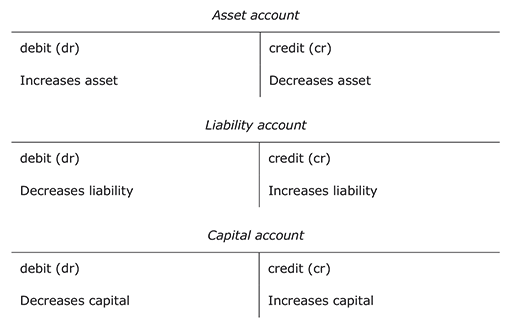

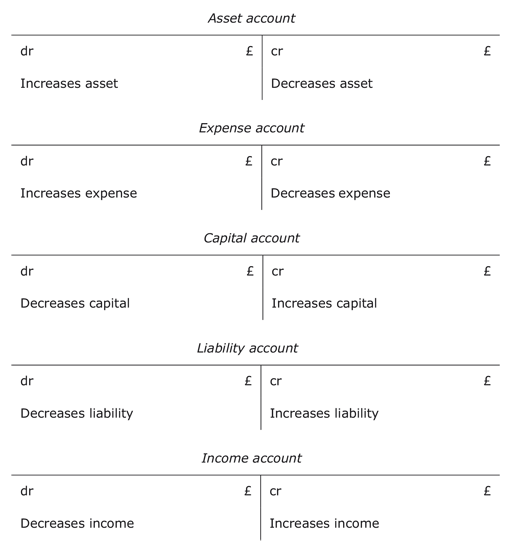

As we have seen in Sections 2.3 and 2.4, because of the dual aspect of double-entry bookkeeping, if one account changes as a result of a financial transaction, then another account needs to change to keep the accounting equation in balance. This is shown in ledger or T-accounts by recording each transaction twice, once as a debit-entry in one account and once as a credit-entry in another account. This is done according to time-honoured rules which treat asset accounts differently from liability accounts and the capital account.

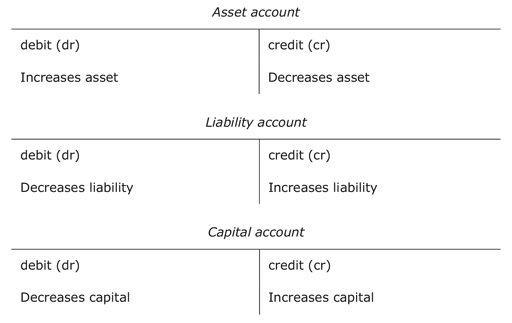

What are the rules of double-entry bookkeeping?

If a transaction increases an asset account, then the value of this increase must be recorded on the debit or left side of the asset account. If, however, a transaction decreases an asset account, then the value of this decrease must be recorded on the credit or right side of the asset account. The converse of these rules applies to liability accounts and the capital account, as shown in the three T-accounts below:

Pause for thought

These rules need to be memorised initially as they are not intuitive. Through seeing how they work in practice and doing exercises they will become second nature – a little bit like learning to swim or ride a bicycle.

The balance on an asset account is always a debit balance. The balance on a liability or capital account is always a credit balance. (Later on in this section you will learn how to work out the final or closing balance on an account which has both debit and credit entries. The process of determining the closing balance on an account is known as ‘balancing off ’ an account.)

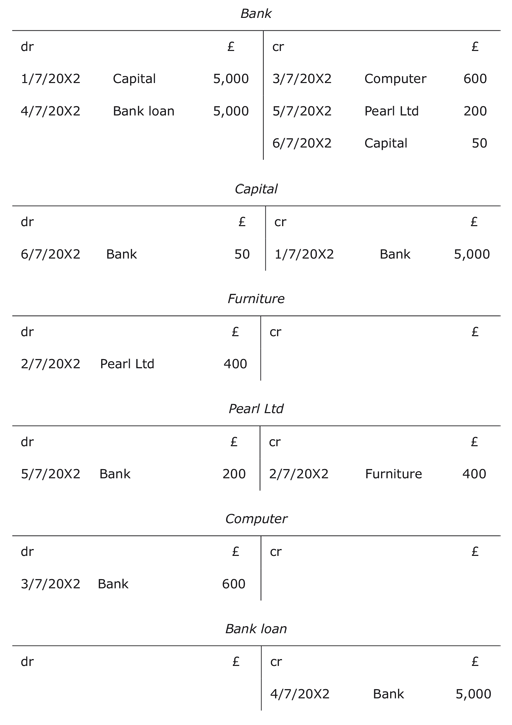

The best way to understand how the rules of double-entry bookkeeping work is to consider an example. We will now record the six transactions carried out by Edgar Edwards Enterprises in the appropriate T-accounts.

Example

Transactions:

- The owner starts the business with £5,000 paid into a business bank account on 1 July 20X2.

- The business buys furniture for £400 on credit from Pearl Ltd on 2 July 20X2.

- The business buys a computer with a cheque for £600 on 3 July 20X2.

- The business borrows £5,000 on loan from a bank on 4 July 20X2. The money is paid into the business bank account.

- The business pays Pearl Ltd £200 by cheque on 5 July 20X2

- The owner takes £50 from the bank for personal spending on 6 July 20X2.

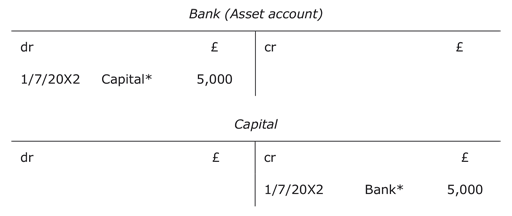

Transaction 1 : The owner starts the business with £5,000 paid into a business bank account on 1 July 20X2. (Following the rules we learnt, we thus need to debit an asset account and credit the capital account.)

* Each T-account, when recording a transaction, names the corresponding T-account to show that the transaction reflects a double entry in the nominal ledger.

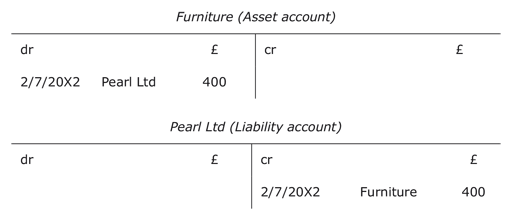

Transaction 2 : The business buys furniture for £400 on credit from Pearl Ltd on 2 July 20X2. (We need to debit an asset account and credit a liability account.)

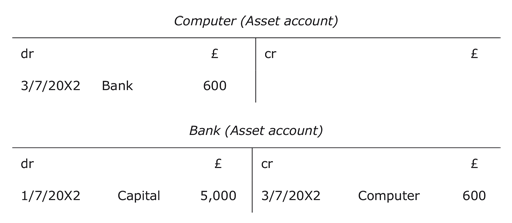

Transaction 3 : The business buys a computer with a cheque for £600 on 3 July 20X2. (We need to debit an asset account and credit an asset account.)

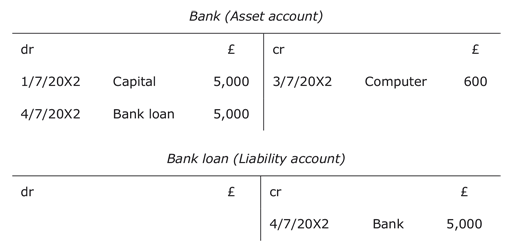

Transaction 4 : The business borrows £5,000 on loan from a bank on 4 July 20X2. The money is paid into the business bank account. (We need to debit an asset account and credit a liability account.)

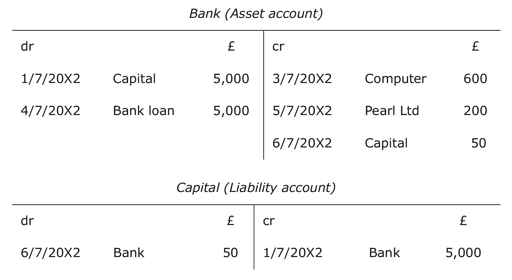

Transaction 5 : The business pays Pearl Ltd £200 by cheque on 5 July 20X2. (We need to debit a liability account and credit an asset account.)

Transaction 6 : The owner takes £50 from the bank for personal spending on 6 July 20X2. (We need to debit the capital account and credit an asset account.)

In Section 2.3 we recorded the consequences of these transactions in a balance sheet for Edgar Edwards Enterprises dated 6/7/20X2. Did you find it easy to do that? As there were only six transactions, it was probably not too difficult. However, many enterprises have to record hundreds of transactions per day. Having individual T-accounts within the nominal ledger makes it much easier to collect the information from many different types of transactions. The next section will explain what is done with the balances in each of these accounts.

2.6 Balancing off accounts and preparing a trial balance

What is a trial balance?

A trial balance is a list of all the balances in the nominal ledger accounts. It serves as a check to ensure that for every transaction, a debit recorded in one ledger account has been matched with a credit in another. If the double entry has been carried out, the total of the debit balances should always equal the total of the credit balances. Furthermore, a trial balance forms the basis for the preparation of the main financial statements, the balance sheet and the profit and loss account.

How do we prepare a trial balance?

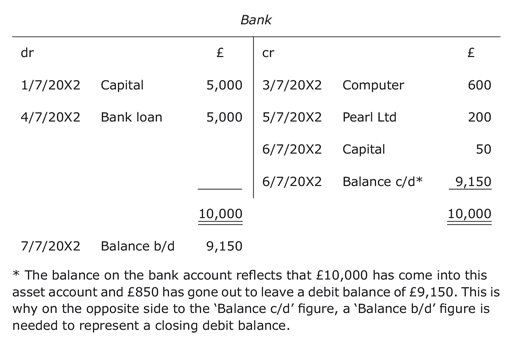

In order to prepare a trial balance, we first need to complete or ‘balance off ’ the ledger accounts. Then we produce the trial balance by listing each closing balance from the ledger accounts as either a debit or a credit balance. Below are the T-accounts in Edgar Edwards’ nominal ledger. We need to work out the balance on each of these accounts in order to compile the trial balance.

What is the procedure for balancing off accounts?

Accounts are straightforward to balance off if they consist of only one type of entry, i.e. only debit entries or only credit entries. In this case, all the account entries are simply added up to get the balance on the account. If, for instance, a bank account has three debit entries of £50 each, then the balance on the account is a debit balance of £150. However, when accounts consist of both debit and credit entries, the following procedure should be used to balance off these accounts:

- Add up the amounts on each side of the account to find the totals.

- Enter the larger figure as the total for both the debit and credit sides.

- For the side that does not add up to this total, calculate the figure that makes it add up by deducting the smaller from the larger amount. Enter this figure so that the total adds up, and call it the balance carried down. This is usually abbreviated as Balance c/d.

- Enter the balance brought down (abbreviated as Balance b/d) on the opposite side below the total figure. (The balance brought down is usually dated one day later than the balance carried down as one period has closed and another one has started.)

Using the rules above we can now balance off all of Edgar Edwards’ nominal ledger accounts starting with the bank account.

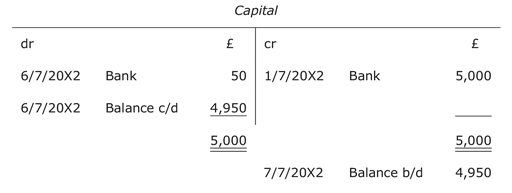

We balance off the capital account in the same way as we did the bank account.

The furniture account has a single entry on one side. This amount is the total as well as the balance in the account.

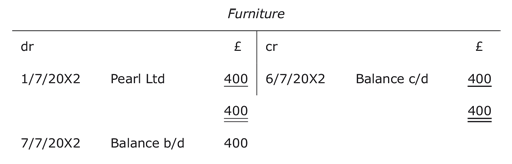

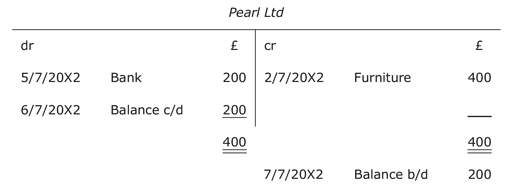

The account for the creditor, Pearl Ltd, has a debit and a credit entry so we will use the method we used for the bank and the capital accounts.

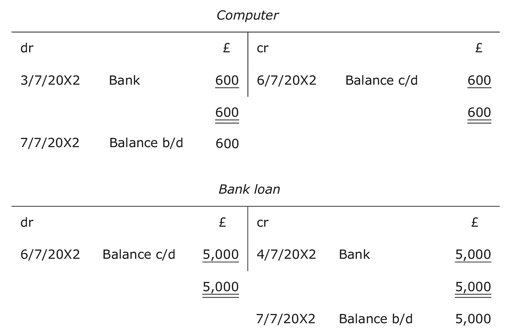

The computer and bank loan accounts have single entries on one side, like the furniture account, so they need to be treated in the same way.

Making a list of the above balances brought down produces a trial balance as follows.

| dr | cr | |

|---|---|---|

| £ | £ | |

| Bank | 9,150 | |

| Capital | 4,950 | |

| Furniture | 400 | |

| Pearl Ltd (a creditor) | 200 | |

| Computer | 600 | |

| Bank loan | 5,000 | |

| Total | Total 10,150 | Total 10,150 |

Information point

From the trial balance we can see that the total of debit balances equals the total of credit balances. This demonstrates for every transaction we have followed the basic principle of double-entry bookkeeping – ‘ for every debit there is a credit ’.

2.7 Summary

- Accounting records are the day-to-day records of all financial transactions and other relevant financial information concerning a business.

- Financial statements are summaries of accounting records to satisfy the relevant financial information needs of stakeholders of a business.

- The owner(s) of a business is (are) the main stakeholder(s) in a business but there are a number of other stakeholders.

- In accounting terms, the business is a separate entity from its owner(s) even if the business is owned by a sole trader with unlimited liability for the debts of the business.

- In accounting terms, the business is a separate entity from its owner(s) even if the business is owned by a sole trader with unlimited liability for the debts of the business.

- Liabilities are debts owed by the business.

- Capital is the owner’s investment in the enterprise.

- The vertical balance sheet of a business reflects the accounting equation: Assets – Liabilities = Capital.

- Financial transactions have two aspects which must be equal to keep the accounting equation in balance.

- Financial transactions are recorded by debits and credits in the ledger accounts (also known as T-accounts).

- Assets are represented by debit balances while liabilities and capital are represented by credit balances.

- The following rules apply to asset, liability and capital accounts.

- To calculate the balance in an asset account we calculate the excess of debits over credits to get the net debit balance.

- To calculate the balance in a liability or capital account we calculate the excess of credits over debits to get the net credit balance

- The balance carried down figure within an asset account is always on the credit side of the account and is brought down as a debit balance.

- The balance carried down figure within a liability or capital account is always on the debit side of the account and is brought down as a credit balance.

3 Double entry and the profit and loss account

Section learning outcomes

By the end of this section you should be able to:

- understand the difference between generating cash and making a profit

- understand how profit relates to owner's capital in the balance sheet and the accounting equation

- understand what the profit and loss account is

- measure profit and loss

- account for closing stock

- state the double-entry rules for income accounts and expense accounts.

3.1 Making a profit and generating cash

What is the main objective of business activity?

Generally speaking, the main reason for the existence of a business is to make a profit for the owner(s) over a defined period. (There are, of course, other objectives that a business might have and the business has to work within the laws and customs of society.)

Profit over a period is achieved by trading successfully, i.e. a business is able to sell goods or services for more than the expenses incurred in producing them in the same period. A loss over a period, on the other hand, is when a business is only able to sell goods or services for less than the expenses incurred in producing them in the same period. If we say that the start of a period is time 0 and the end-date of a period is time 1 then the profit or loss for this length of time can be expressed by the formula:

Profit or loss 1–0 =Income 1–0 –Expenses 1–0

Information point

Income is a wider concept than sales as it includes all earnings in a period. Income thus includes interest received, rent received, etc. as well as cash and credit sales.

What is the difference between making a profit and generating cash in an accounting period?

Profit is when income earned, by cash or credit, is greater than expenses incurred, by cash or credit, in the same accounting period.

Generating cash over an accounting period, by contrast, is when cash inflows are greater than cash outflows in the same period. Cash inflows and outflows in a period may be completely unrelated to income and expenses as they may be based, for example, on a financial event that is unrelated to income and expenses, such as the owner introducing capital into the business or drawing capital out of the business.

What is the formula to work out how much cash is generated in a period?

To work out how much cash is generated in a period we need to work out the difference between the cash balance at the end of a period (time 1) and the cash balance at the beginning of a period (time 0). This can be expressed in the formula:

Cash generated 1–0 = Cash 1 – Cash 0

The next activity should give you an insight into the common situation in business where the profit made in a period is not the same as the cash generated in the same period.

Activity 17

Andrew and Barry have recently started exactly the same business – buying and selling music CDs. They each started their trade on 1 January 20X1 with £1,000 entirely borrowed from the bank. Both Andrew and Barry bought their CDs for cash but Andrew decided to allow his customers to buy CDs on credit as he believed this would generate more sales.

In the first week of trading Andrew bought CDs for £800, all cash, and sold them all for £1,600 – all on credit. Barry, on the other hand, bought CDs for £400, all cash, and sold them all for £800 cash.

Required

Part (a)

(a) Assuming that Andrew and Barry had no other income and expenses in the week, use the formula Profit 1–0 = Income 1–0 – Expenses 1–0 to calculate each of their profit for the week.

Answer

Andrew’s profit for the week = £1,600 – £800 = £800

Barry’s profit for the week = £800 – £400 = £400

Part (b)

(b) Assuming that Andrew and Barry had no other transactions in the week, use the formula Cash generated 1–0 = Cash 1 – Cash 0 to calculate each of their cash generated for the week.

Answer

Andrew’s cash generated for the week = (£1,000 – £800) – £1,000 = –£800 (i.e. £800 of cash is lost in the week)

Barry’s cash generated for the week = (£1,000 + £800 – £400) – £1,000 = £400

Part (c)

(c) What do your answers to (a) and (b) tell you about the effect of credit sales on profit earned and cash generated in a business?

Answer

The answers tell us that credit sales may generate more profit in a period (Andrew’s profit compared to Barry’s) at the expense of losing cash (Andrew’s negative generation of cash compared to Barry’s).

From the activity above we have seen that it is possible for a business to make a profit in a period but lose cash in the same period. The reason for this is that the different transactions in the activity above had different effects on profit earned and cash generated in the same period. The next activity should help you to better understand this.

Activity 18

Use the box below to complete answers for Table 13. Indicate the effect (either none, increase or decrease) on profit and/or cash of the following eight transactions. The first four transactions relate to the transactions completed in Activity 17 while the last four transactions refer to likely further transactions of the businesses in Activity 17.

| Effect on profit | Effect on cash | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Receipt of a loan | |||

| 2. Buying stock for cash | |||

| 3. Making a cash sale | |||

| 4. Making a credit sale | |||

| 5. Receiving cash from a debtor | |||

| 6. Buying stock on credit | |||

| 7. Payment for stock bought on credit | |||

| 8. Repayment of a loan |

Answer

| Effect on profit | Effect on cash | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Receipt of a loan | none | increase | |

| 2. Buying stock for cash | none* | decrease | |

| 3. Making a cash sale | increase** | increase | |

| 4. Making a credit sale | increase** | none | |

| 5. Receiving cash from a debtor | none | increase | |

| 6. Buying stock on credit | none* | none | |

| 7. Payment for stock bought on credit | none | decrease | |

| 8. Repayment of a loan | none | decrease |

* It is only when stock is sold that there is an effect on profit. Later in this section you will see that when stock is sold the value of the stock that is sold becomes an expense called cost of sales. At that stage there is an effect on profit, but only an effect on cash if the goods or stock is sold for cash not credit.

** This increase in profit assumes the normal situation where goods are sold for more than they are bought – such as the example of the CDs in Activity 17. If goods are sold for less than they are bought then the effect will be a decrease in profit.

How does making a profit in a business relate to the capital of a business?

We have already learnt that the capital of a business is the value of the investment in the business by the owner(s). If the business makes a profit then the value of the investment by the owner (or capital) increases. The best way to understand how this works is to look at the effect of profit on the accounting equation.

3.2 The effect of profit on the accounting equation

In Section 2 we looked at the three elements of the accounting equation – assets, liabilities and capital – and how these three elements are presented in the balance sheet. However, a business’s trading activities, i.e. its income and expenses incurred in order to generate profit, are not shown in the balance sheet.

Below is an abridged balance sheet of a firm at the beginning of a financial period and before any trading has taken place.

| Assets | £ |

|---|---|

| Premises and equipment | 40,000 |

| Stock | Total 6,000 |

| Total assets (A) | 46,000 |

| Liabilities | |

| Creditors | Total 19,000 |

| Total liabilities (L) | Total 19,000 |

| Net assets (A – L) | Total 27,000 |

| Capital (C) | Total 27,000 |

Included in the firm’s stock account at the beginning of the year are seven cameras that cost £100 each. On the second day of the year, the business sells one of these cameras for £175 cash. The firm will thus have gained £75 on this transaction.

How is this profit-making sale reflected in the accounting equation?

If we analyse the transaction, Peter’s Photographic Enterprises (PPE) has received £175 cash from the customer, so that means net assets are increased by £175.

(Net assets of £27,000 + £175 = £27,175)

At the same time, an asset has disappeared. The stock will be down by one camera, and so that must be reflected in the accounts.

(Net assets of £27,000 + £175 cash – £100 stock reduction = £27,075)

If you remember, we established that the main objective of the business was to generate profit for the owners. That is what has happened here, the business has gained an asset of £175 against giving up a camera that cost £100. In other words, the transaction has resulted in an income of £175 and an expense of £100. The transaction has thus created a profit of £75 (£175 – £100) for the owners assuming there are no other expenses.

(Net assets of £27,075 = Owner ’s capital of £27,000 + £75 profit or increase in owner ’s capital)

The accounting equation thus balances, but the business has other expenses that need to be taken into account. Suppose PPE buys advertising for £30 cash. This will reduce the profit created by £30 as well as reducing cash.

(Net assets of £27,075 – £30 (decrease in cash) = Owner’s capital of £27,075 – £30 (decrease in capital))

What would be the effect on the balance sheet of the two transactions above?

After this a new balance sheet can be drawn up showing net assets of £27,045 and capital of £27,045. The business has made a profit or financial gain of £45 since the previous balance sheet. The balance sheet, however, does not give a breakdown of profit into income and expenses and for that we need the profit and loss account that will be discussed in more detail in the next section.

What is the new accounting equation once Income (I) and Expenses (E) are included?

The net figure of income less expenses is calculated at the end of the financial period in the profit and loss account. This net figure, either a profit or a loss, is then transferred to the capital account. The accounting equation can be extended to show this change to capital: A – L = C + (I – E).

Information point

You should realise from the equation A – L = C + (I – E) that if a business makes a profit in a financial period (i.e. I > E) then capital (C) will have increased for the business over the financial period. If a business has made a loss in a financial period (i.e. I

3.3 The profit and loss account

The profit and loss account is a financial statement which sets out the results of the trading activities of an enterprise in a detailed breakdown of income generated and expenses incurred. Different businesses have different breakdowns of income and expenses and hence present financial information in the profit and loss account in different formats. However, the overall or net profit recorded in the profit and loss account for any business is also the amount by which the balance sheet value of the business has increased.

What are the formats of the profit and loss account?

The format of the profit and loss account (P&L account) will vary depending on whether the business is a manufacturing concern (i.e. making goods they sell) or a non-manufacturing concern (i.e. either buying goods for resale or selling a service for a fee).

Information point

Whatever the nature of the business, each type of income or expense has its own account in the nominal ledger like the balance sheet items we looked at in Section 1.

What is the difference between net profit and the other important form of profit?

The most important profit for a business is the net or overall profit. It is the increase in the financial value or worth of a business after all expenses have been deducted from income. The second most important form of profit is the gross profit. This is the difference between sales and the cost of the goods or stock sold, known as the cost of sales. Gross profit is thus the profit earned by a business before the overheads or general expenses of running the business such as advertising, rent, salaries, and heating and lighting are deducted. The difference between gross profit and net profit will become clearer to you as we look at a number of examples in this section.

3.4 Income and expense accounts

A successful business will have many transactions and, rather than take the profit or loss to owner’s capital on each transaction, similar income or expenses are collected together in separate accounts in the nominal ledger. These accounts are totalled at the end of a time period (at least once a year but probably each month as well) to measure the total profit or loss for that period. The P&L account, when published as a financial statement, is a summary of all the income and expense accounts that reflect the year’s trading transactions.

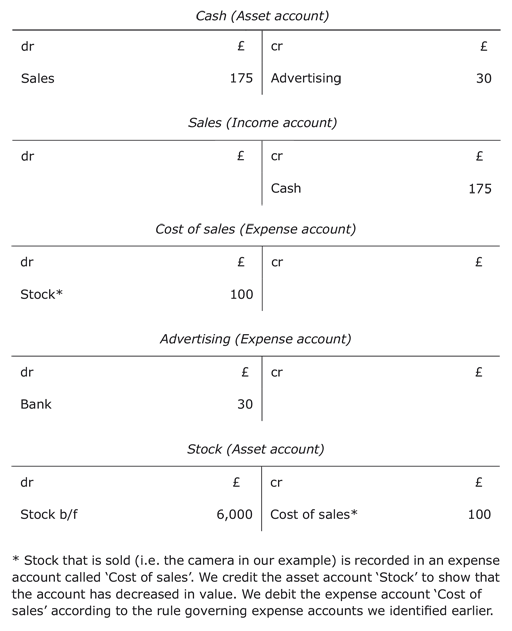

As with assets and liability items, items of income and expense are recorded in nominal ledger accounts according to set rules. Expenses are always recorded as debit entries in expense accounts and income items are always recorded as credit entries in income accounts.

We will now look at Peter’s Photographic Enterprises’ initial transactions as they would be dealt with in the nominal ledger.

We could prepare a P&L account from those T-accounts that we indicated were either income accounts or expense accounts.

| £ | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sales (Income account) | 175 | |

| Cost of sales (Expense account) | Total 100 | |

| Gross profit | 75 | |

| Expenses | ||

| Advertising (Expense account) | Total 30 | |

| Net profit for the period | Total 45 | |

| The effect on the balance sheet would be: | ||

| Assets | ||

| Increase in cash | +£145 (the increase in the cash T-account) | |

| Decrease in stock | –£100 (the decrease in the stock T-account) | |

| Liabilities | ||

| No change | ||

| Change in net assets | +£45 | |

| Capital | ||

| Profit | +£45 |

Information point

In the example above the net profit of £45 is not the same as the increase in cash of £145. As we learned in Section 3.1, net profit is often very different from the increase or decrease in cash in the same period.

Activity 19

A business carries out the following cash transactions:

- a.business buys stock of bicycles for £1,000

- b.customer pays £300 for one bicycle (cost of bicycle is £200)

- c.business pays £45 for electricity.

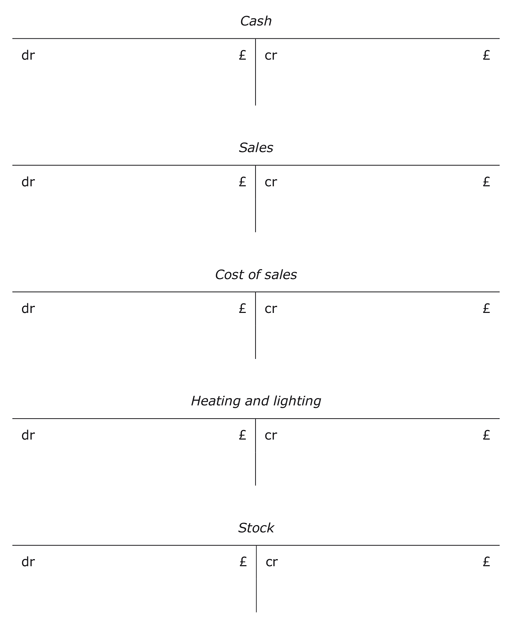

Enter these on the T-accounts below, and draw up a P&L account.

Answer

| £ | |

|---|---|

| Sales | 300 |

| Cost of sales | Total 200 |

| Gross profit | 100 |

| Expenses | Total 45 |

| Net profit | Total 55 |

3.5 Accounting for closing stock

The bookkeeping for stock transactions can be done in a number of different ways.

In an ideal world, the bookkeeping entries would follow the physical flow of the goods:

- accumulate purchased supplies in a stock account – an asset account in the nominal ledger

- when an item is sold, transfer it to a cost of sales account – an expense account in the nominal ledger

- at the end of the period, transfer the balance in the cost of sales account to the P&L account in order to work out the gross profit.

This is how we did it in the example above of Peter ’s Photographic Enterprises’ sale of a camera. In practice, however, this method is inefficient in a context where there are many transactions and they each have a low unit value. For example, if you were running a grocery store, you would not want to carry out a bookkeeping transaction to transfer each item sold from stock to expense.

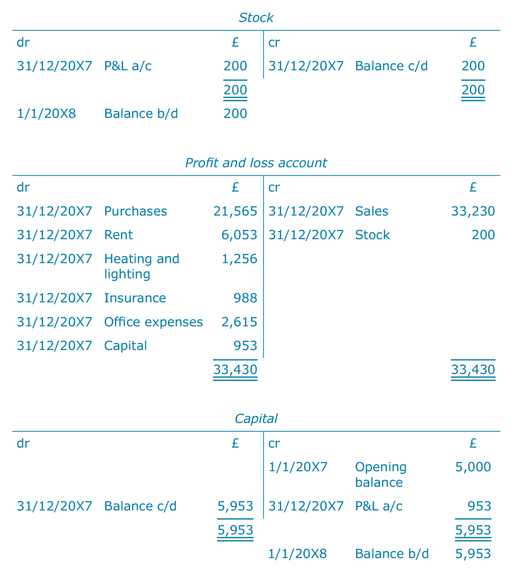

From here on we will therefore use a simplified procedure that assumes that as the business buys goods for resale, they are immediately treated as an expense, called purchases, in the ledger. Then, at the end of the accounting period, the value of the closing stock (i.e. stock remaining at the end of the period) is deducted from purchases to show as cost of sales only the value of stock or goods sold in the period.

Information point

This section deals only with closing stock, the stock that is normally determined at the stocktake on the last day of the accounting period.

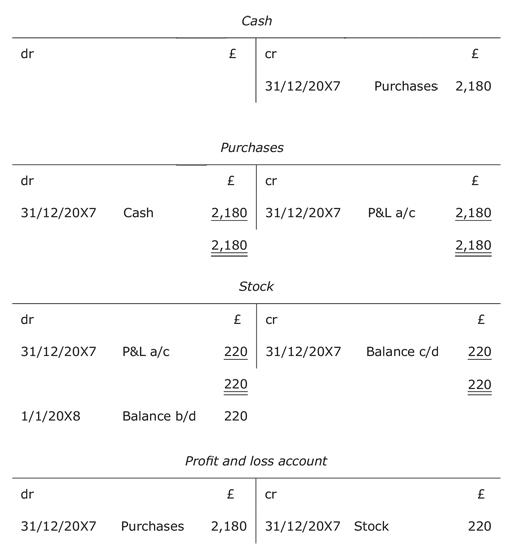

What would be the T-account entries for a business which, in the course of the financial year ended 31/12/20X7, bought goods for cash to the value of £2,180 and had a closing stock of £220 on the last day of the financial year?

Information point

Unlike the stock account, the cash account has not been ‘balanced off’. This is because cash purchases (i.e. £2,180) were not all of the cash transactions for the business during the year. In the real world, cash and stock are both assets of a business and they need to be ‘balanced off’ at the end of the period.

The P&L account now shows cost of sales, the value of stock used up in the period, i.e. £2,180 (Purchases) – £220 (Closing stock) = £1,960.

All accounts are ruled off at the period end to show the end-of-period balances that are transferred to the trial balance. Liability and asset accounts (like the stock account above) are said to be ‘balanced off ’. This involves bringing the balance forward to the next accounting period. On the other hand, income and expense accounts (like the purchases account above) are ‘closed off ’ because no balance is brought forward to the next accounting period. The balance in every income and expense account is brought to zero at the period end by a double entry to the P&L account.

In the example above, what was the double entry to ‘close off’ the purchases account?

The purchases account was ‘closed off ’ for the year by crediting the purchases account by £2,180 and debiting the profit and loss account by the same amount.

Information point

You should have noticed from the example above that the P&L account is not only a financial statement like the balance sheet, but is also the name of a nominal ledger account. In general, when we refer to a P&L account we are referring to its meaning as a financial statement and not as an account in the nominal ledger.

The following activity shows how we complete the P&L account, in its conventional form as a financial statement, from closing balances in income and expense accounts.

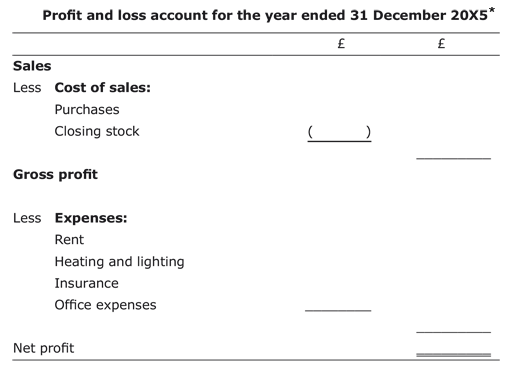

Activity 20

A small business, with no opening stock, has the following closing balances in its income and expense accounts for the financial year just ended on 31 December 20X5:

- Sales £21,568

- Purchases £10,261

- Rent £4,568

- Heating and lighting £756

- Insurance £329

- Office expenses £287

At the last day of the year a stocktake was carried out and the stock figure for the year was £987.

Using the template for the P&L account given below, ‘close off’ or transfer the balances above to the P&L account and work out the net profit for the year.

*In the format of the P&L account as a financial statement, the two columns do not represent debits and credits. The purpose of the first column is to give sub-totals, when required, for the totals that make up the second column.

Answer

*The cost of sales in the profit and loss account above is £987 less than the purchases for the year because it excludes the closing stock of £987, which is included in the purchases figure.