Professional relationships with young people

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 20 April 2024, 4:32 PM

Professional relationships with young people

Introduction

Relationships are a central aspect of all our lives. We have many relationships, through which we learn the social skills necessary to survive and thrive. Relationships lie at the heart of all effective work with young people and are the foundation upon which you can build your work with them.

In some people’s eyes, the development of relationships is a good end in itself, as it is in relationships that we express our humanity. Young people with few good quality relationships in their lives often find that entering into informal relationships with adults who respect, accept, like and really listen to them is a new life experience. These relationships can offer the young people new perspectives on approaching, developing and managing quality relationships of their own.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of level 1 study in Education, Childhood & Youth.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

identify the importance of developing positive professional relationships with young people

recognise the qualities and attitudes which support the development of professional and helping relationships

describe what a ‘good’ professional relationship is, and some ways to develop them

demonstrate awareness that ending relationships positively is as important as planning to develop relationships.

1 Professional and/or helping relationships

For practitioners working with young people, good-quality relationships are fundamental to their work. The trust engendered by strong relationships enables workers to encourage young people to try new experiences, take some risks and perhaps acquire new learning. These new experiences may involve the young people in taking a fresh look at themselves or exploring new roles and new identities. Alternatively, they may be drawn outwards to join new groups or learn about, and possibly take action within, their communities. They might even do both.

That said, developing relationships isn’t always easy. In fact, developing relationships with young people can be very challenging. Young people might not want to develop a relationship with you at all: they may be confrontational or disengaged. We recognise that there are challenges and different approaches to developing work with young people. Some practitioners work with young people on an entirely voluntary basis, e.g. the young people come to a project because they want to. Other projects or programmes may not facilitate voluntary participation: for example, those with young people who have to attend after being excluded from school.

Activity 1 Professional and / or helping relationships

For this next activity, read the article entitled Helping Relationships.

- As you read through this article, pay particular attention to the section on ‘The Helping Relationship’ on page 4. In considering the nature of a helping relationship this section refers to the work of Carl Rogers (1951; 1961); his ideas about the key qualities and attitudes that facilitate learning are discussed. Make notes about these.

- Now think about these qualities and attitudes and how they support the development of relationships you have experienced. Choose three and make a list from 1 to 3, with 1 being the most important in the development of effective relationships and 3 the least important.

- Now jot down your thoughts about the core qualities discussed:

- a.Are there any which you feel he has left out?

- b.Do they relate to your own principles?

Discussion

Your top three will probably be unique to you because everyone has different experiences of developing relationships. Each of us has our own preferences in relationship building and it’s useful to have started the process of reflecting on the qualities and attitudes involved. You may also have noticed some discussion about Gerard Egan, whose book The Skilled Helper (2002) introduced the idea of helping within professional relationships. ‘Helping’ in this context refers to establishing quality conversations with young people, listening and exploring issues and problems with people; these are all skills in working with young people which help build effective relationships.

1.1 Relationships in practice

Having thought about the qualities involved in developing relationships, let’s now discuss what we might consider a ‘good’ relationship. Which factors constitute a ‘good’ relationship? This is of course a complex question, and your answers will reflect your own values, the values of the young person and those of the organisation you work for. A ‘good’ relationship almost certainly has to strike a balance between different and sometimes competing aims and values – for example, between fostering a sense of security for young people and challenging them to try out new ideas and activities. How is your relationship different from the other types of relationships the young person might have?

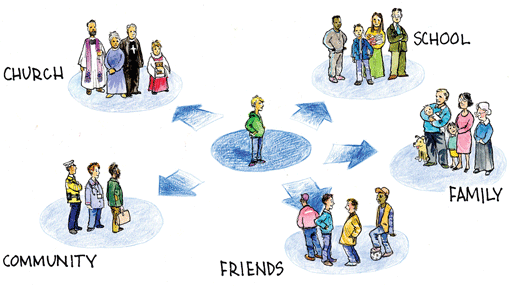

This drawing represents the people in a young person’s life. There is a young man at the centre. On the outside are a series of drawings representing people from his school, family, friends, community and church.

When we consider our relationships with young people and whether they are ‘good’ relationships or not, we must weigh up the evidence for our response. Are we relying on our personal opinion or did we draw on conversations with colleagues or something we read? We might think the relationship was positive, but do we know what the impact was? Can we measure the outcome?

For example, briefly speaking in a personal capacity as the author of this study guide, I consider my relationship with Emily [a young person I worked with], as ‘good’ because I was able to support her in quitting smoking. She trusted me enough to help her give up and I felt that I could therefore ‘measure’ an outcome. Proving that the relationship supported that outcome is trickier, but seeking out the opinions of other people, your colleagues or the young people concerned can help.

You can ask young people themselves about their views and experiences of a ‘good’ relationship. Their feedback can provide important insights for your work practice and evidence for your practice and studies. Alternatively, or in addition, you can keep a record of key conversations you had with the young person, or of observations you made during your encounter with them. This way you can capture how relationships change. Relating any changes in the young person’s thoughts, feelings or actions to your own interventions can be difficult. With this in mind, the more evidence you collect the better as this allows you to assess the impact of these interventions.

Remember that the success or lack of success in building the relationship is not just up to you. As mentioned earlier, the nature of relationships we have with young people may be voluntary or, from time to time, compulsory. You should know that sometimes there will be occasions when it simply doesn’t go the way you hoped and that this is not your fault. This is when evidence on practice can help us, and using feedback from young people can certainly inform our assessment of our relationships with them.

A good starting point is to find out what the young people might want from a relationship with you as a professional. To do this properly you need to talk to young people.

1.2 Young people’s needs, interests and concerns

The purpose of youth work is to allow young people to participate, to empower young people, to promote equality of opportunity and to challenge oppression. Although this was proposed by the Second Ministerial Conference on the Youth Service, which took place in 1990, all of these purposes are still relevant to the building of effective relationships because good relations enable you to help and guide young people to make their own decisions and choices. You might have specific ideas about how you will do this, but in this next activity we want you to reflect both on your ability to see things from young people’s perspectives and your use of their perspectives in your conscious planning around relationship building.

Activity 2 Understanding young people

Now think about one or more of the young people you know or work with. Jot down your responses to the following questions about them:

- Which three things do they most like about themselves, and what three things do they most dislike about themselves? (For example, their personal appearance, personality and confidence, perceived talents and weak spots, ability to attract and keep friends or lovers, their good character or their ‘wild side’.)

- Which identities are most important to them? How important, for example, is their religion, ethnic origin, gender, age, sexuality, group of friends, the youth culture or lifestyle they espouse (music, dress, club affiliations)?

- Which topics are guaranteed to spark a lively conversation? For example, what are their favourite football teams, television programmes, leisure interests, etc.? Which political issues do they feel strongly about?

- How would they define their needs? And how might you distinguish those ‘needs’ from ‘wants’?

- How are they getting on at school (academically, socially and with staff) or at work? Are they coping or struggling with their academic work at school, or their social relations with fellow students or work colleagues, with teachers or managers? Are they respected or bullied?

- What resources do they have? What are their main sources of support, financially and emotionally, and how reliable are these supports?

- What are their main ambitions in life, and what are the main obstacles standing in their way?

Discussion

As Reid and Fielding suggest, ‘Identifying the individual needs of a young person may involve formal or informal processes’ (2013, p. 90). In considering what evidence you have for your views of young people, you should always think about the extent to which you can trust the source of your information. The questions above are very demanding and a reminder of just how much there is to know about every one of the young people you work with. Now you’ve responded to these questions, stop and think about your responses. Firstly, were all the questions relevant for young people? Where there any which weren’t represented (e.g. sexual orientation, religion, faith or language)?

How do you know what you know? Are your responses based on intuition, or do you have evidence to support your views? Maybe you weren’t able to make detailed notes, but it’s worth considering:

- the extent to which you base your understanding of young people on your own intuition, your personal preferences and assumptions

- whether or not you base your perspective on evidence of any kind, especially young people’s own views

- how much you need to know about a young person’s background before you start to build a relationship with them?

Ultimately, you will want to make sure that, in making decisions about how to help or support young people, you have listened and understand what they want help or support with. We also need to consider what to do with this information. How are you expected to collect young people’s information? Where and how is this stored? Making sure you are familiar with your organisation’s procedures can ensure that what you collect is ethical and will not have negative implications for you or a young person. This is part of understanding your role in helping young people and developing relationships with them. Let’s now look further into your roles in relationship building.

1.3 Roles and activities for building relationships

Two characteristics that differentiate a professional relationship with young people from a personal one are the roles you play and the activities you use to promote young people’s learning and development.

There are seven key characters that practitioners take on, or act out, in their work with young people. These roles, and their underlying purpose, are summarised in Table 1.

| Role | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Ally | To provide support and approval; show commitment through thick and thin; encourage a ‘can-do’ attitude and bolster self-esteem |

| Emotional worker | To model and promote emotional literacy; the ability to recognise and handle feelings in oneself and in others |

| Catalyst | To provide the stimulus for change; challenge the assumptions that young people have about themselves and others; open the doors to new experiences |

| Mentor | To provide information, advice and learning opportunities; help young people to develop skills such as decision making; encourage young people to think through why they do what they do and what might enhance their life chances |

| Advocate | To act on behalf of young people when they don’t have confidence, but build their skills and confidence for self-advocacy |

| Facilitator | To help young people achieve tasks; manage group dynamics, recognising when to step in and when to let young people find their own way |

| Supervisor | To create an environment in which young people feel safe, physically and psychologically |

These are not rigid categories from which you must choose just one; rather, they illustrate the range and variety of the roles that you may be called on to play, depending on such factors as:

- the young people you are working with

- any issues that the young people (or you) might be facing

- the stage of the relationship you are forming

- organisational demands for accountability

- organisational context.

It is common for practitioners to feel most comfortable, and to operate most strongly, in particular roles: some may prefer to be a Facilitator, while others want to be an Advocate. With careful planning (and a little luck), an organisation will seek to put together a balanced team so that young people have access to practitioners playing a variety of roles. Even better, each worker learns to be flexible. The role you play will also depend on whether your work involves formal or informal education.

Activity 3 Thinking about the roles you play

You may decide to focus on trying out different roles. To do this effectively you first need to ask yourself about the type of role you play, what influences your choice and the context in which you use your roles in working with young people. Make a note of your responses to the following questions.

Type of role

Are you conscious of the roles you play in your relationships with young people? Make a list of these roles.

Why do you think your role may differ? Is it because you are working with different young people? On the other hand, perhaps it has something to do with the values guiding your work with young people?

Do some roles fit your views on the wider purpose of building relationships with young people? Alternatively, could it have more to do with the kind of person you are (or think you are)?

Influences

What helps or hinders your attempts to act in different roles with different young people in different situations? Having considered your own organisation’s policies in earlier study guides, are there any organisational constraints? Are you conscious that some roles are looked on more favourably by colleagues or your line manager?

Context

Can you think of situations in which you believe a young person would like you to be acting in one role, whereas you think another would be more appropriate? Describe one such situation and reflect on the reasons for this. You could discuss this with the young person and record how their opinion influenced your thinking.

You could also open up a discussion with a young person on the roles you might play, by focusing on roles young people want you to play.

Discussion

This activity is personal to you, so there are no right or wrong answers to these questions. Having considered which role you currently play, you are now in a better position to understand how you might adopt other roles and why.

Working with young people traditionally involves engaging in practical activities – sometimes in pursuit of educational goals, sometimes with a ‘health and fitness’ agenda, sometimes with a ‘community development’ orientation. You may associate such activities more with group work, but they are also useful as a tool and, as a context, for developing relationships. Engaging young people in activities that they find pleasurable means they are more likely to be relaxed and to chat with people around them. In addition, by allowing them to choose activities they want to take part in, you can get to know more about their interests and their talents, as well as provide the sense of safety needed in the early stages of building a relationship. By offering a range of activities, you can support young people in their own personal development – cajoling and confronting them, when you feel that your relationship allows it, to encourage them to extend themselves. Whether you decide to concentrate on your role or a particular activity, you will also need to consider the skills you need to develop and manage the different phases of your relationships.

2 Skills in relationship building

The way we spend our time with young people is important in developing our relationships with them. We talk a great deal with young people in planning and running activities, we listen to their needs, issues, problems and achievements, we share their concerns and this enables us to offer help and support. The basic skills required for effective relationship building involve:

- listening

- conversing

- observation.

They are fundamentally important to relationship building. As we have already said, building relationships with young people is not always easy. Some young people may be confrontational and not want to engage with you at all. An important skill here, which builds on the basic relationship-building foundations (listening, conversing and observation), is that of managing conflict, which we will now consider.

2.1 Challenges in relationship building

There is a tendency to see conflict and differences of opinion as difficult and to be avoided; and yet one of the main ways in which we learn and grow is by coming into contact with new ideas and behaviours. When we are feeling strong, we may try these out for ourselves to see whether or not they work, yet at other times, we may feel threatened and either retreat from the conflict or lash out in exasperation. Young people also experience these emotions. The basic relationship-building skills: listening, conversing and observing can help you build the types of relationships with young people that can respond to such emotions, calm potential conflict and support young people’s development.

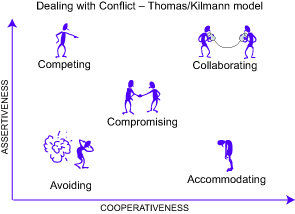

Working within the context of management and organisational development, Kenneth Thomas (1975) identified five styles for managing conflict:

This image looks like a graph with an X and Y axis. The Y or vertical axis represents assertiveness. The X or horizontal axis represents cooperativeness. There are five styles for managing conflict placed at appropriate points on the graph. ‘Competing’ is high in Assertiveness but low in Cooperation. ‘Avoiding’ is low in both Assertiveness and Cooperation. ‘Compromising’ is in the middle of both. ‘Accomodating’ is low in Assertiveness but high in Cooperation. ‘Collaborating’ is high in both.

Looking at these styles, you might be able to identify the one you use most and the skills you use to achieve these. In Thomas’s view, most people tend to lean towards one or other of these styles by the time they reach adulthood. However, he suggested that in fact what we need to do is develop the full range of styles and be flexible enough to know how to operate different styles in different situations and to recognise which style would be most appropriate. Therefore, here is a short description of each style which we hope gives you a starting point for developing ways of handling similar situations in your own work.

- Competing: People tend to behave as if they are sure they are right and are keen to make sure they win an argument, get their own way and achieve their own goals.

- Accommodating: The people using this style want to be liked. They tend to do what they think others want them to do.

- Avoiding: Those using this style usually try to avoid conflict at all costs. They may even try to avoid the people they anticipate conflict with, and not want to raise contentious issues. They hope that, by avoiding conflict, those issues will just disappear – although in fact the situation may get worse if the issues are not aired and resolved.

- Compromising: This approach involves some give and take – ‘I will do this for you if you will do that for me’.

- Collaborating: In this approach, people put their heads together to come up with a way of everybody getting what they want – what is known as a ‘win–win’ situation.

In terms of working with young people, the collaborative approach to conflict resolution is the one most likely to demonstrate that your attitude towards a young person is principled and respectful. Young people will recognise that you are taking them and their views most seriously when you listen to them and try and talk through new solutions to a problem together. We also need to recognise that there are times when we do have to tell young people how it is because they might be acting unsafely or doing something which is against the law. We are, after all, responsible for the safety of the young people we work with.

When you are trying to resolve conflict, you may take a different position to the young person, but listening carefully to what they are saying will help you identify common ground. Furthermore, if you involve others who can offer new perspectives on the situation, you are demonstrating that you are not being dogmatic, but are genuinely trying to find a solution that is acceptable to both of you. The ladder of collaboration below presents the five key steps in the collaborative process.

This image is of a ladder with five rungs. The bottom rung, and the first step, represents ‘separate the person from the problem’. The next rung and second step represents ‘clarify the problem’. The third rung and next step represents ‘explore a variety of options’. The fourth and penultimate step represents ‘focus on acheiving a solution’ and the final rung and step represents ‘agree the outcomes’.

In the next activity, we want you to reflect on your own approach to managing conflict. You are also encouraged to get into the practice of reflective action for academic writing.

Activity 4 Thinking about managing conflict

Jot down examples of two situations when you dealt with conflict.

Then choose one of these conflict situations and write a brief outline of the situation. Explain:

- the style of conflict resolution you adopted, and why – do they relate to any of Kenneth Thomas’s styles?

- if you made a conscious decision to handle the situation in that particular way, or whether you were simply doing what you felt was right at the time

- why you think it worked well

- how you might you have handled it more productively overall.

Discussion

In conflicts, you can often separate the young person from the problem by demonstrating through your words and your body language that you respect them, even if you don’t like what they are doing. Feelings can get in the way of thinking. If the young person feels under threat, you are less likely to find a creative solution with them. It is also your professional duty to treat young people with respect. We should challenge the comments but never the young person. We also need to be polite – ‘I’ve noticed that you have been late three times now’, rather than ‘You’re such a pain in the neck, you’re always late’. You can also take the route of opening up the discussion rather than defining the problem yourself. Ask the young person what they think the problem actually is and find out if the young person has a possible solution.

You can use your listening skills to really identify the young person’s side of the argument. Keep an open mind about the outcomes, and keep using non-confrontational phrases such as ‘I’m not sure I understand that – could you explain what you mean?’ That way you can check that you have a proper understanding of their position and can clarify the problem.

If clarifying the problem hasn’t led to a breakthrough, it is time for both of you to contribute a range of alternative solutions to the decision-making process. If you can keep an open mind and your prejudices at bay, you may find that the person you are arguing with actually has a clearer idea of the issues and the solutions than you do. Even if this is not the case, your listening allows them to offload any anger or misery that may lie at the heart of the conflict. They will then be able to think more clearly, to feel valued and, therefore, more inclined to contribute to a discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of your different perspectives. You could also agree to collect information to shed more light on the matter. Agreeing on the outcomes together will enable you to work out a plan of action and for checking on progress towards them.

2.2 The stages of relationships

In the first activity you read about helping relationships and how we need to know ourselves in order to act as a good role model to young people. You need to cultivate certain skills in yourself, as you will be acting as this role model (Ingram and Harris, 2013). Through you, young people can learn and develop skills such as:

- caring and being cared for

- disagreeing and remaining friends

- negotiation and compromise

- developing relationships that are open, honest and based on trust.

By helping young people to learn from their successes and failures, you support them in developing a mind-set of being able to manage relationships rather than them feeling as though they’re at the mercy of others.

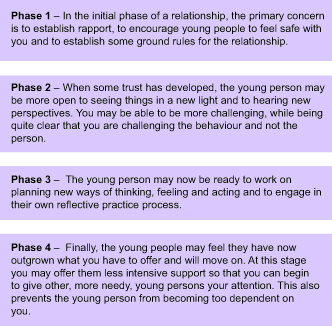

The way in which you respond to young people may well depend on which phase in the relationship you have reached. If you have only just met them, building an effective relationship will involve using effective communication skills, listening attentively and using appropriate body language to build up trust and respect. Alternatively, you might be at the stage where you have got to know a young person really well, you have supported them through change and they are ready to move on. A useful model that many practitioners adopt in order to reflect on their relationships is that identified by Gerard Egan (2002). Egan identified different stages of relationships and his work provides a useful model to analyse the different stages in our own relationships with young people. We have summarised the eight steps Egan proposed into four phases, as shown in Figure 4.

How comfortable are you with the different phases or stages of relationships? Relationships go through different phases, and you are likely to feel more comfortable with some than others. You need to consider carefully why this is so, and to ensure that you do not neglect an important phase just because you are less comfortable with it.

This is a representation on Gerald Egan’s four stages of relationships. Each stage is represented in a text box, one on top of the other, with the first stage at the top. The first stage represents ‘the initial phase of a relationship; the primary concern is to establish rapport, to encourage young people to feel safe with you and to establish some ground rules for the relationship.’ The second stage represents ‘When some trust has developed, the young person may be more open to seeing things in a new light and to hearing new perspectives. You may be able to be more challenging, while being quite clear that you are challenging the behaviour and not the person.’ The third stage represents ‘The young person may now be ready to work on planning new ways of thinking, feeling and acting and to engage in their own reflective practice process.’ The fourth and final stage represents ‘the young people may feel they have now outgrown what you have to offer and will move on. At this stage you may offer them less intensive support so that you can begin to give other, more needy, young persons your attention. This also prevents the young person from becoming too dependent on you.’

If you prefer the early phases of relationships (rapport building and offering new perspectives), you may regard the later phases as rather instrumental – focused on ‘changing’ young people for the ‘better’ (perhaps meeting some government agenda) rather than allowing them to use the organisation for their own purposes (which might simply be for rest and relaxation).

If you feel most comfortable in the earlier stages of the relationship, you may feel uncomfortable about the more ‘challenging’ aspects as the relationship develops. As you saw earlier, in the styles for managing conflict, some people do their best to avoid any form of conflict, seeing it as almost wholly negative rather than as something that might be very valuable if appropriately handled. In developing effective relationships you will need to have a range of skills for the different stages of the relationships you have. You also need to build up your confidence and competence in relationship building and the ending of a nonprofessional relationship.

2.3 Endings are as important as beginnings

The end can be seen as a sad occasion, but in the professional arena the decision to move on can be seen as part of a growing maturity. The ending is often a stage that we spend little time on: however it is important as you are helping young people move on to a more independent level. It is a positive stage and hopefully you will feel able to say, ‘That’s good – I see you have learnt something then’. Earlier on we talked about the need for evidence in demonstrating the outcomes of your interventions. Endings are good evidence of young people’s learning. However, endings can be more problematic when they are brought about by lack of funding, for example, rather than by natural progression.

Activity 5 Working at the ending stage of the group

Read the chapter ‘Working at the ending stage of the group: separation issues’ by Jarlath Benson. You may wish to make a note of any key points which interest you or which you would like to remember for the future. However, the point of this activity is simply to develop your understanding of the issues inherent in ending group work.

Whatever the cause of the ending of your relationship with young people, it is likely to elicit a mix of emotions for all those involved. A sense of loss or bereavement is not unusual and even with pre-planned endings youth workers need to programme plenty of time to discuss and evaluate the relationship and identify next steps. How we as professionals handle these transitions is the final way that we can role model positive behaviour to young people whilst working with them.

Conclusion

This free course provided an introduction to studying Education, Childhood & Youth. It took you through a series of exercises designed to develop your approach to study and learning at a distance and helped to improve your confidence as an independent learner.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Dr Kate D’Arcy, Tyrrell Golding, Fiona Reeve and Rajni Kumrai.

This free course is adapted from a former Open University course called 'Working with young people in practice (E118).

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated in the acknowledgements section, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Course image: National Assembly for Wales in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Licence.

Figure:

Figure 2: www.earthpm.com

Text:

Activity 5 reading: Benson, Jarlath (2010) 'Working more creatively with groups', (2nd Ed.) Abingdon, Routledge - Chapter 7 Working at the ending stage of the group: separation issues, courtesy of Jarlath Benson.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University