History of reading tutorial 1: Finding evidence of reading in the past

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 18 April 2024, 7:06 AM

History of reading tutorial 1: Finding evidence of reading in the past

Introduction

For researchers in a range of academic disciplines, the question of what people read in the past, and how they read it, is of great importance. Evidence of reading helps us to understand the formation of literary canons, both from a popular and educational standpoint. It allows us to give due weight to the impact of significant texts at key historical moments, especially their role in shaping popular ideas and opinions. For instance, knowing who read, how many read, and how they responded to Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species helps us to understand the formation of Victorian ideas about evolution and race.

This tutorial is about locating evidence of reading and using that evidence to better understand how past societies have made use of text. We will begin by looking at debates about the different types of evidence and methods of collection. Next we will focus on some of the diverse sources that have been used to populate UK Reading Experience Database (RED), analysing their merits and value. Finally, we will explore ways of extracting sets of data from UK RED and applying quantitative and qualitative methods of analysis to arrive at some conclusions about reading in the past.

Find out more about studying with The Open University by visiting our online prospectus60

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

demonstrate a basic knowledge of the debates about the evidence of reading, understanding distinctions between ‘hard’ or quantitative data and ‘soft’ or qualitative data

understand an overview of some of the types of evidence scholars have used to construct the UK RED and their relative merits as primary sources

identify different sources when looking at individual entries in the UK RED

experiment with applying different methods of analysis to sets of records in the UK RED, including the application of quantitative and qualitative methods.

1 Debates about where to find readers

Debates about ‘the reader’ – from his or her importance in the life of a text, to means of identification – have raged for some time. At first, this field was dominated by theorists who looked to the text to provide clues as to its audience. So, looking at the arrangement of the text in manuscripts and later printed books, Paul Saenger argued that in Europe during the Middle Ages, there was a great shift in reading practice from reading aloud to reading silently. In 1970, Hans Robert Jauss suggested that readers brought to texts a ‘horizon of expectations’: this was created by a reader’s encounter with other texts that gave him or her an understanding of literary conventions and thus determined his or her response to the text in question.

At the same time, the emergence of the field of ‘book history’ brought new perspectives and research methods to the history of reading. So-called ‘hard evidence’ relating to texts was introduced to determine the size of the readerships of given works. Publishers’ archives have been mined for print runs, sales and circulation figures for books and newspapers; public and circulating library borrowing records have been uncovered to demonstrate how often various titles were requested; the contents of private libraries have been catalogued; and even literacy rates have been used to estimate the size of the reading public. This evidence is considered to be ‘hard’ because it is measurable or quantifiable: knowing how many copies of a particular title were sold over a defined period of time can tell us something about peaks and troughs in the desire of readers to own such a book. This kind of evidence has led to the construction of grand narratives about the practice of reading over the longue durée: for example, both the increasing size of libraries and the growth of print runs for books and magazines during the eighteenth century encouraged some scholars to suggest that men and women began to read more widely but less intensively.

But – did the men and women who bought a copy of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations actually read it? If they did, what did they think of it? These are two major questions that cannot be answered accurately by the ‘hard’ evidence of book history. However, there are other, more personal historical records, documents which captured moments in time when men, women and children felt the need or were forced to disclose information about their reading habits. Journals, diaries, memoirs and autobiographies are the most obvious sources for this type of research and over the last fifty years there have been many detailed and illuminating studies on the reading tastes and practices of individuals who left behind such personal accounts.

At the core of UK RED rests the notion of a ‘reading experience’, that is, a recorded engagement with a written or printed text beyond the mere fact of possession. The evidence collected in UK RED is therefore mostly anecdotal or personal. But contributors have gone beyond the traditional sources used for studying reading, such as diaries and autobiographies, and found a plethora of reading experiences in a range of other observational and inquisitorial records. Moreover, the sheer quantity of data collected in UK RED, combined with its diversity, is eventually intended to highlight key patterns in the history of reading over the longue durée.

2 Evidence of reading experiences

In this section, we will look in detail at some of the types of sources used to compile UK RED and consider what each set might contribute to our understanding of reading in the past. Thinking hard about these sources should not only help you to become critical of the different types of evidence used for studying reading, but also suggest some pathways for your own research.

Before we delve into different categories of evidence in detail, it might be worthwhile to point out exactly where the details of the source from which the reading experience is derived are located. Source information can be found right at the bottom of the page which displays the record details. Let me walk you through the process:

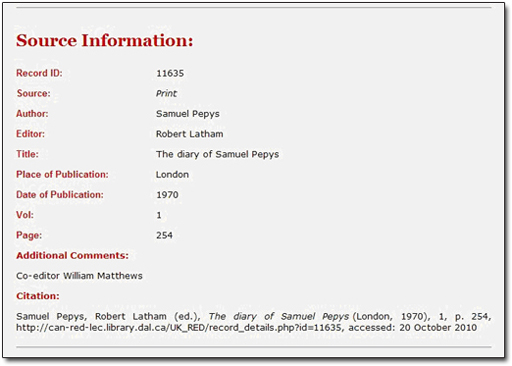

Go to the advanced search and under reader, type in ‘Samuel Pepys’ (right-click on the link to open it in a new tab or window). You should get close to 400 records. Select any record from the list – click on the coloured link to go to the record details. Then, scroll down until you get to a section called ‘Source Information’. It should look just like this:

In this case, I clicked on Samuel Pepys reading John Speed’s A Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World, (UK RED: 11635). The source for this is Samuel Pepys’s diary, which was edited from the original manuscript by Robert Latham and William Matthews and published in 1970. All this information is laid out in the relevant fields. At the very bottom we also supply citation details. If you are citing evidence from UK RED, it is crucial that you use the UK RED citation rather than referring to the original source. That is because UK RED represents a ‘publication’ of that source, and if there are any errors in the transcription, these remain our responsibility. This allows anyone reading your work to accurately assess where you gathered your information from.

It might be worth spending a few minutes now to become acquainted with the different ways in which evidence is described. For example, the Pepys entry comes from a published book. In UK RED, there are many entries that come from manuscript sources, like this one: evidence that John Buckley Castieau, the Melbourne prison governor, read Gil Blas comes from his manuscript diary stored at the National Library of Australia. Because of the range of sources for the evidence of reading, sometimes the description of the source defies print or manuscript classification. Details for these sources have been entered in the ‘other’ section on the contribution form, and appear like this: this evidence came from a court transcript which has been digitised as part of the Old Bailey Online project. Although the original source was a published pamphlet, the use of the Old Bailey Online method of citation acknowledges their digitisation of the collection and directs the user of UK RED back to the original source quickly and easily.

2.1 Diaries, journals, autobiographies and memoirs – the anecdotal sources

Let’s start with those sources most commonly used to study reading experiences and which are often most rich in evidence: diaries, journals, memoirs and autobiographies. There are slight but crucial differences between these types of sources. Journals and diaries vary widely: some list events in a very methodical way; others are more creative personal texts, composed of reflections on events or encounters that have captured the attention of the diarist. Both, however, are written near the time of the event they record.

Conversely, autobiographies and memoirs are often written many years later and therefore bring the benefit (or not) of hindsight to the events recollected. Memoirs are a ‘subclass’ of autobiographies. In other words, while autobiographies are meant to be a narrative of one’s life, from the cradle to the grave (or almost), memoirs often focus exclusively on one aspect of an individual’s life, covering, for example, one’s professional life but not his or her personal life. Memoirs are therefore thought to be more selective than autobiographies.

If reading has been a key part of someone’s life, reference to it is likely to show up in that individual’s autobiography or memoir. However, the mention of reading in these sources is likely to represent a partial account of one’s entire encounter with text – probably only those works believed to have had a marked impact on thoughts or actions will be referred to by the writer. Favourite novels might be described at length, but the habit of reading, say, The Times, each morning at the breakfast table may not be judged significant enough to record. But where books or other texts are mentioned in these sources, the reader’s response to them is often detailed and invaluable. Depending on the style of the writer, diaries and journals may contain the same level of detail about reading response, but because they form a daily record, are also more likely to include references to everyday reading habits.

UK RED contains evidence from a large number of manuscript and published journals, diaries, autobiographies and memoirs. Many are from famous individuals, such as Pepys. But the database also contains evidence of reading from a large number of diaries and autobiographies written by ‘common’ men and women, especially in the nineteenth century.

Scholars often wonder how representative the reading tastes and habits of the famous, or the literary-inclined actually were. We can use the evidence in RED to put this to the test. Let’s compare the reading list of a famous nineteenth-century female writer with an ordinary working man of the same period.

Activity 1

Go to the UK RED home page (right-click on the link to open it as a new tab or window) and select browse from the navigation bar, or use the quick search/ browse box on the right-hand side. Select to browse by readers with surnames beginning with ‘E’. Scroll down the list until you find George Eliot, and click on her name. You should have arrived at Eliot’s profile. Here you will see Eliot’s personal details; if you scroll down you will be able to see a list of books and other titles that Eliot read. For the most part, these have been derived from Eliot’s diary (remember that some have not – we will come back to this in just a moment!).

I want you to keep that window open, and open a second alongside it using this link. What we have here is a profile page for a male diarist of the same period as Eliot. Thomas Burt was a pitman in the north east who eventually became an MP. Burt was born a little later than Eliot, but as readers they were contemporaries. The list of texts that Burt read has been derived from his autobiography: we have, at this point, few diaries of working men in UK RED, as such a large number. However it is useful to compare Burt’s later recollections of his reading with the more contemporaneous record kept by Eliot.

- Take a look at the lists side by side (you can resize both windows so that you can look at the lists in this way). Is there any similarity – are there texts that both have read? I notice that both read a good deal of Shakespeare. And both read Thomas Babington Macaulay’s History of England. Burt also read Eliot’s novel, Adam Bede.

- Find a text that both read, and then for each click on the evidence to see how they responded to that text. How much detail about the reading do they provide? Were the circumstances in which each read that title similar or very different? Were their reactions to the text similar or different?

Comment

I clicked on Macaulay’s History of England for both. I was struck by how differently the experience was described. I think this is in large part to do with the difference in the source type: Eliot’s diary entry is very short and to the point (UK RED: 7234), while Burt mentions the impact of the text on him – he read it with excitement and to his educational advantage (UK RED: 6870). They both read the text around the same time: Eliot in 1855 and Burt during the next decade. But while Burt read History of England in his mining town in Northumberland, Eliot read the book in Berlin. As well as reading a portion of History of England, Eliot also read two other texts that evening, one of Shakespeare’s plays, and the manuscript of an unpublished essay by her partner, George Henry Lewes. Burt does not mention if he read any other texts at the same time, or whether he read History of England all in one sitting, or over a stretch of time.

As you will have noticed from the amount of detail we were able to extract from the activity above, diaries, journals, autobiographies and memoirs are very useful for studying the history of reading. However, it might be a good moment to sound a note of caution with respect to these sources. Diaries, journals, autobiographies and memories could well be unrepresentative sources. It takes a certain degree of self awareness, not to mention time and materials (very important considerations when thinking about the working classes in history), for an individual to commit themselves to writing a diary or journal. Similar constraints apply to writing an autobiography, and memoirs are most often compiled by those who have enjoyed fame in their lifetime.

Also, especially with regard to those diaries and autobiographies which are published, we must ask whether the account tallies with the reality, or in other words, does the author have an interest in telling us a particular story? Remember I said earlier that not all the titles on the list of George Eliot’s reading were derived from her diary. For example, this experience was extracted from one of her letters. Did she record that reading experience in her diary as well? Take a moment to check now. Select the title from the list of texts that Eliot read, and check the individual reading experiences associated with that text.

The possibility of selective memory has often been raised by those who look at the writing of nineteenth-century autodidacts: these men (there are very few women autodidacts) may well have claimed to read things they did not, or neglected to mention various low publications which they did read and enjoy, in the pursuit of a self-image dictated by the establishment. And even when these men (or women) wrote sincerely about their reading experiences, we must be aware in the case of autobiographers and memoirists that the passage of time between the event and the recording of it may well have had an impact on the truth of their recollections.

2.2 Inquisitorial sources – glimpses on common practices?

Evidence of reading experiences can also be harvested from sets of inquisitorial sources in which ordinary people were compelled either directly or indirectly to reveal this information. Like the sources described above, these are most effectively used alongside other sources for the history of reading, especially as each carries its own methodological limits or particular bias. When you encounter these sources in UK RED, it is crucial that you consider the conditions in which the readers offered information about themselves.

Let’s consider a couple examples here. Sociological (or anthropological) studies form the first type of inquisitorial source. UK RED contains evidence of reading from several large bodies of work by social scientists in the nineteenth- and early-twentieth centuries. These men and women set out to observe life in Britain and, as part of this, to interview men, women and children about their daily habits. Henry Mayhew’s famous study of the working classes of London, London Labour and the London Poor, compiled during the 1840s and 1850s, reveals much about the struggles and pleasures of those who lived below the bread line. You can read a summary of some of his findings here. Mayhew also completed a large volume on prison life which also included evidence of reading.

Activity 2

Let’s take a look at the various reading tastes that Mayhew’s interviews with the labouring poor uncovered. Go to the UK RED search page, and type ‘Mayhew’ into the keyword field for a basic search. I got 97 hits, which is quite a lot. What I’d like you to do is just casually scroll down the list of results. Are there any titles or authors that you recognise amongst these 97 records?

Comment

I saw quite a few texts for which the title could not actually be identified. This may have been because the questions asked encouraged answers that were too general, about reading tastes rather than specific works. Alternatively, this may be because some of the texts these readers spoke about were ephemeral and so very difficult to identify. However, I did notice that the Bible featured quite prominently amongst these hits, which suggests that it must have continued to loom large in the experience of the lower orders in the nineteenth century, despite some contrary evidence historians have presented of secularisation. I also picked out some very well known titles, including Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, Milton’s Paradise Lost, and Shakespeare’s works. At the same time, a good proportion of the titles seemed to be of the mass entertainment kind, sensational works such as Ainsworth’s Jack Sheppard. This brief survey suggests to me that it is very difficult to categorise the tastes of the poor in literature, that their tastes were very diverse. Moreover, the results show that nineteenth-century urban labourers had access to a wide variety of texts and titles.

Mayhew brought his own assumptions and prejudices to bear on his sociological surveys – he was not shy about commenting on some of the reading tastes of those he interviewed and observed and certainly thought there was room for improvement! However, less obvious but equally important are the preconceptions and assumptions that his interviewees brought to the event. Some historians have questioned the extent to which we can rely on many of the testimonies Mayhew published. Put simply, when interviewed by someone of a higher social position who not only intended to publish the story but also potentially had methods of relief to offer, did these poor men, women and children tell Mayhew the truth or tell him what they thought he wanted to hear? Or, at another level, how many of these interviewees attempted to put the story of their lives into a framework which Mayhew could understand and appreciate – not necessarily a truthful story, but nevertheless a sincere one?

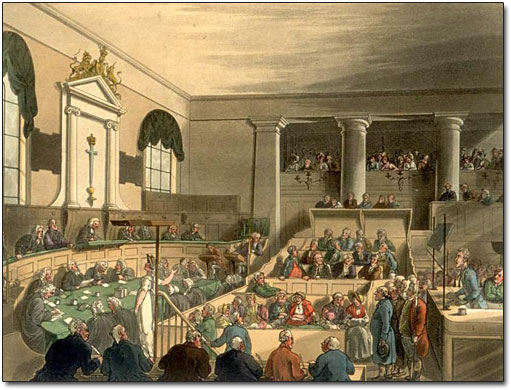

Mayhew’s interviewees were asked directly about their reading. There are other sources in which ordinary men and women were asked very different and seemingly unrelated questions which lead them to expose some information about their reading habits or experiences. Criminal court records are one such source. Transcripts of trials, such as the Old Bailey Proceedings, but also newspaper summaries of courtroom evidence, abound with references to reading. Reading was often an activity that witnesses remembered doing on the day of the crime, or reading articles about the crime had led witnesses to the courtroom. A large number of these incidents have been entered into UK RED. You can find a substantial proportion of these by searching for ‘old bailey’ as keywords in the basic search. Let’s try that now.

Activity 3

Go to the UK RED search page and type ‘old bailey’ (without the quote marks) into the basic keyword search. How many hits did you get? When I tried, the database returned just over 200 results, which is a lot.

If you gently scroll down the list of results, you might notice that newspaper has a large presence in the type of text that these readers made reference to. Some reading historians have claimed that newspapers and other ephemeral texts were probably read more by people in, say, the 18th and 19th centuries, than books, but commented on less. Using a source like the Old Bailey which captures a very different kind of evidence might help to redress that balance.

We can use the entries collected from the Old Bailey Proceedings to try some valuable qualitative analysis of newspaper reading habits or practices in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Select around five of these entries, randomly from the big list. If it makes it easier, you can mark five entries and export them into ‘my list’. Next, take a quick look at the details of each entry – clicking on each (or from the PDF generated in ‘my list’). Look at the evidence of reading they offer, and then at characteristics of that experience (noting, for example, the socio-economic group and occupation of the reader; the place where the reading occurred, and so on). From these five entries, can you detect any patterns about newspaper reading that this source might illuminate?

Comment

Here are the five samples I collected: entry one; entry two; entry three; entry four; and entry five (right-click on each link to open it in a new window or tab). What struck me first was the diversity of these entries, but then I noticed that they all seemed to belong to different categories of experience the telling about which had been directly encouraged by the circumstances of the courtroom and the likely questions asked of the witnesses. So in the first in my list, the Polish jeweller, Philip Farmer, heard another read the notice of the trial and that meant that Farmer then went to the court. Publican of the Two Brewers, William Spicer, featured in my second entry, remembered reading the newspaper as he recounted events leading up to the crime: the reading was incidental, and might have been part of his routine. The next two entries both catalogued the experiences of pawnbrokers, who had used the newspaper (in both cases the Daily Advertiser) to detect whether the items customers were pledging were actually stolen property. And finally, in my last, the accused claimed he found the forged bank notes in the street and went to the pub each day to see if the notes had been advertised as lost in the newspaper, presumably so that he could return them to his owner. I also noticed a pattern across these entries: that the newspaper featured prominently in public life – people went to the pub or the coffee house to read it, and some heard it being read aloud in a public venue.

The potential offered by court records is enormous. But our excitement about this potential should not prevent us from being critical about the evidence offered by this source. A large proportion of the evidence in UK RED taken from court records inevitably relates to the reading of crime news. For example, the entries we explored in some detail revealed that many of the witnesses were pawnbrokers, who seem to have read the newspaper to avoid accusations of being receivers of stolen goods. But when looking at this type of evidence, it is always useful to pose a counterfactual – what about those people who read the crime news and did not go to court, even though they had seen the stolen goods, witnessed the crime, or knew the accused? Could it be that those who did not go to court are of a greater number than those who did? Do court records reveal the ‘tip of the iceberg’, or do they point towards the reading habits of a small minority?

3 Using UK RED to understand reading in the past – collating the evidence

If all the types of evidence described in this tutorial are potentially unrepresentative or hampered by a particular bias, then the best and perhaps only way we can truly recover common reading habits and tastes in the past is by collating the evidence: using them together, comparing and contrasting the type of reading they describe.

UK RED is built in such a way as to make collation seamless. Searches using set criteria return records from all sources. Over time, as the records in UK RED continue to grow in number, we should be able to run searches which reveal patterns of reading in the past. In other words, by putting these qualitative sources into a database with set values within fields, we might be able to apply quantitative methods in order to exploit their potential to the full.

Activity 4

First, open the UK RED search (right-click on the link to open it in a new window or tab). Use the advanced search functions to fill in the table below. In the second column, fill in the number of entries that the database contains for each century (in the advanced search, tick the century only then click submit). Next, combine searches for entries relating to specific half centuries with each subject category (for example, select 1800-49, and then under genre/subject, select fiction), and record the number of entries. For the third column, ‘religion’, make sure you tick ‘sermons’, ‘religious texts’ and ‘Bible’ to cover the range of this category.

Next, you will need to arrange your results to demonstrate the proportion that each category of reading represented for each half century. Click on the button to calculate the percentage share of each category.

What patterns do you see appearing in the table? Click the button again to see my results when I did the exercise in January 2011.

Comment

Looking at my tables, I was surprised by the extent to which the data in UK RED confirmed the grand narrative. Poetry does decline over the course of this period; at the same time fiction is on the increase. Religious reading also declines, but I was also interested to see how prominent it remained in people’s experiences.

I hope that exercise was useful and illuminating. But quantitative analysis does have its limits. It may be that the exercise we just completed tells us more about the available sources for the history of reading than about actual reading in the past, and therefore we should not be surprised that it confirms some previous scholarship.

To be used effectively, quantitative history should not be applied in isolation. For example, we could use UK RED to count the number of people in each decade of the Victorian period who read Charles Dickens’s books. This search, however, would not tell us how many of those people enjoyed reading Dickens, or how many found that one of his books had a decisive impact on their lives. The individual records of reading need to be looked at as well and assessed alongside the bare lists of results. And the sources which provide the data need to be analysed, and compared, to determine the value of the evidence offered.

4 Conclusion and further reading

I hope this tutorial has given you an understanding of some of the various sources used to compile UK RED and how you might assess their value to the history of reading. Also, I hope it has encouraged you to try to locate other sources not already contained in the database which might form the basis for your own research project. Most of all, I hope that it has introduced you to a range of methods of analysis, qualitative and quantitative, that you will be able to apply in your own work.

And remember, if you come across evidence of reading from the past that is not yet in UK RED, please do contribute your research to the project: your evidence is vital to our understanding of reading in the past.

Further reading

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Dr Rosalind Crone.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Course image: Rick Manwaring in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Licence.

Figure 2: Samuel Pepys by John Hayls, 1666, © National Portrait Gallery

Figure 3: Old Bailey Courthouse, Wikipedia

Figure 4: Waiting for the Times, 1831, by Benjamin Robert Haydon, Private Collection/Bridgeman Art

Waiting for the Times, 1831, by Benjamin Robert Haydon, Private Collection/Bridgeman Art

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University