History of reading tutorial 2: The reading and reception of literary texts – a case study of Robinson Crusoe

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 25 April 2024, 7:32 AM

History of reading tutorial 2: The reading and reception of literary texts – a case study of Robinson Crusoe

Introduction

The purpose of this course is to demonstrate how the UK Reading Experience Database (UK RED) can be used in a study of the reading and reception of a literary text.

The example chosen for the case study is Daniel Defoe’s famous novel, Robinson Crusoe (1719), and the course takes the student through the process of locating evidence of reading Robinson Crusoe that is included in RED, and then, by means of exercises and linked ‘discussions’, shows how this evidence can be analyzed, and conclusions drawn from it.

In working through this particular case study, students are learning not only about the reception of Robinson Crusoe, but are learning how to make a similar study of the reception of any literary text or author that they may be interested in.

Find out more about studying with The Open University by visiting our online prospectus60

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

locate data in UK RED to help study the reading and reception of a literary text

analyse individual reading experiences contained in UK RED

understand how evidence from UK RED might be incorporated into arguments about the wider significance of reading as a cultural practice.

1 Overview

A focus on the reception of texts by readers has been one of the most striking developments in modern literary studies. In very broad terms we might say that the attention of critics over the past two hundred years or so has shifted from a concern with the author (the biographical approach of the nineteenth century); to a concern with the text (the ‘words on the page’ approach of New Criticism); and finally, most recently, to a concern with the process of reading and the role of the reader in the construction of meaning. Many of the various strands of contemporary literary theory, however different in other respects, recognise in one way or another that literary texts need to be understood not in isolation, but in relation to specific acts of reading and to the responses of readers.

One of the most influential of these approaches over the past 20 or 30 years has become known as ‘reader response criticism’. For the most part, ‘reader response’ theorists have been concerned with hypothetical readers and acts of reading, and have attempted to understand reading processes and activities by studying texts themselves. More recently, however, a number of literary scholars and historians working within the new discipline of Book History have begun to focus attention on actual readers from the past. A great deal of empirical evidence has been uncovered by these scholars not only about what readers read, but about the circumstances in which they read, and about the impact their reading had on them.

UK RED was set up to collect as much information as possible about British readers, at home or abroad, between 1450 and 1945, and to make this information available in an easily searchable form to anyone interested in any aspect of the history of reading. The purpose of this course is to help you learn how to use UK RED to locate and analyse evidence of the reading and reception of a literary text. I’ve chosen as my example one of the most famous novels ever published: Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe.

2 Robinson Crusoe

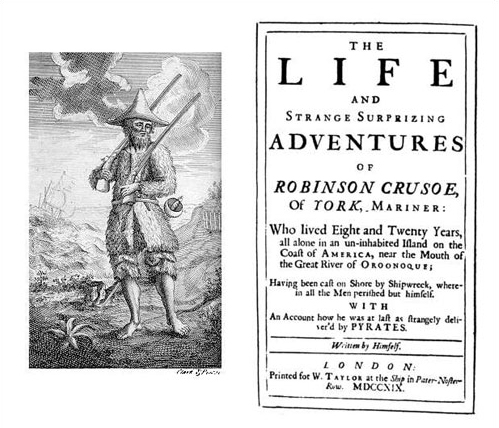

From the moment of its first publication in April 1719, Daniel Defoe’s novel Robinson Crusoe was a commercial success. By the end of the year five further editions had been published, and pirated copies and abridgments had already begun to appear (a sure sign of real popularity). It went on to become one of the most frequently published novels in the English language, with nearly 1,200 separate editions up to 1979. It also attracted imitations, which were produced in such large numbers that they form an identifiable genre known as the Robinsonade. Among the most famous of these Robinsonades were works like The Swiss Family Robinson by a Swiss clergyman Johann David Wyss, translated into English from German in 1814, and The Coral Island (1858) by the Victorian children’s writer R. M. Ballantyne.

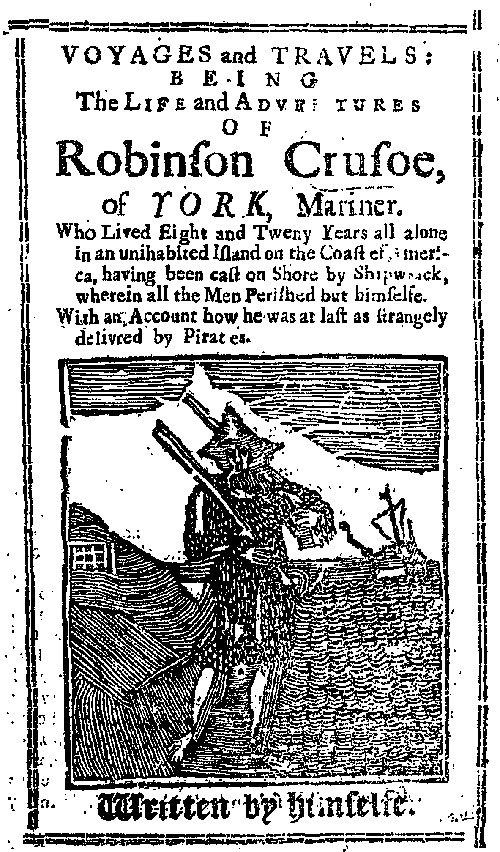

Many scholars have attempted to account for the extraordinary popularity of Robinson Crusoe and its imitations, and have speculated about what it was that readers were responding to in Defoe’s book. Pat Rogers, to take one example, made an intensive study of the history of publication of Robinson Crusoe in chapbook form, looking particularly at what was included or omitted in these cheaply produced and radically shortened versions of the novel.

Rogers concluded that the readers of these chapbooks were responding to Robinson Crusoe as ‘a story of survival, as an epic of mastery over the hostile environment, as a parable of conquest over fear, isolation and despair’. However persuasive this conclusion may seem, it can be little more than one scholar’s guesswork. To move beyond guesswork we need to study evidence of the responses of actual readers, and UK RED offers a quick and convenient method of accessing such evidence.

Activity 1

As a first step, please now go to the UK RED site and check out how many references it contains to Defoe and to Robinson Crusoe. You can use the ‘Basic search’ facility, which searches all the fields, putting in first ‘Defoe’ and writing down the number of results, and then ‘Crusoe’ and writing down the number of results. You should then use the ‘Advanced search’ facility, in which you can go to the ‘Author being read’ box and put in ‘Defoe’, and then go to the ‘Text being read’ box, and put in ‘Robinson Crusoe’. In each case you then scroll down to the bottom of the page and press ‘Submit query’ and a new page will open with the results. These searches will give you a quick indication of the amount of material included in RED about the reading of Defoe and his famous novel. When you have done this, compare your results with mine in the ‘Discussion’ box below.

Comment

I carried out these searches of RED in September 2010. Using the ‘Basic search’ I got the following results:

- ‘Defoe’ = 139

- ‘Crusoe’ = 215

An ‘Advanced search’ gave me the following results:

- ‘Defoe’ as ‘Author being read’ = 76

- ‘Robinson Crusoe’ as ‘Text being read’ = 52

The results you get may well be different, because RED is an ever-growing resource, with new data being added all the time. But these figures give you an idea of the substantial quantity of information that is there to be studied and analysed.

You might have wondered why a basic keyword search for ‘Defoe’ or ‘Crusoe’ returned so many more results than an advanced search for the author ‘Defoe’ or the title ‘Robinson Crusoe’. The answer is that the basic keyword search looks for the specified term in every text field of the database. This means that it will return entries where ‘Defoe’ or ‘Crusoe’ are mentioned, even if they are not necessarily the author or text being read.

For instance, a reader might have purchased ‘Robinson Crusoe’ on the day they also bought ‘Jane Eyre’, but because they only read ‘Jane Eyre’ that evening, ‘Jane Eyre’ is recorded as the text being read. Or again, someone reading some other travel narrative might have been reminded of the story of ‘Robinson Crusoe’, so again ‘Crusoe’ might appear in the evidence of the experience, even though it was not itself the text that was being read.

The point to remember is that using the ‘advanced search’ to search for ‘Robinson Crusoe’ as the text being read will give you very specific evidence about the reception history of Defoe’s novel; but searching for ‘Crusoe’ using the basic ‘keyword search’ will bring up all mentions of the text. This wider information might itself be of interest, and add another layer to the analysis. For example, it might be the case that ‘Crusoe’ was a book often bought or referred to, but not read; or that ‘Crusoe’ was so widely read that readers often referred to it when discussing their reading of other texts; or that ‘Defoe’ was such a famous author that he was frequently referred in discussions of reading.

Activity 2

I’d now like you to do some further searches, to begin to get a more detailed breakdown of the readers of Robinson Crusoe by ‘age’ and ‘gender’. So, return to the ‘Advanced search’ facility, and enter ‘Robinson Crusoe’ as the ‘Text being read’. Then scroll back up and press the ‘Child (0–17)’ button (beside ‘Age’ under the heading ‘Reader/Listener/Reading Group’), and ‘Submit query’. Make a note of the number of entries you are given, and then go back in to ‘Advanced search’ and do the same procedure, except that this time press the ‘Adult’ button.

When you have got your breakdown of ‘child’ and ‘adult’ readers, carry out the same exercise to get information on the numbers of ‘male’ and ‘female’ readers. Remembering always to enter ‘Robinson Crusoe’ as the ‘Text being read’, press the ‘male’ button in the ‘Readers’ section, and make a note of how many there are, and then do the same for ‘female’ readers, making a note of how many there are. When you have done this, compare your results with mine in the ‘Discussion’ box below.

Comment

My results (in September 2010) for the age breakdown of readers were as follows:

- ‘child’ readers = 32

- ‘adult’ readers = 15

You will note that the total here, 47, is fewer than the total of 52 we got by searching for all readers. What this means is that the age of five of the readers entered in RED is not known.

My ‘gender’ breakdown was as follows:

- ‘male’ = 41

- ‘female’ = 11

3 Childhood reading of Robinson Crusoe

We know from many sources that Robinson Crusoe was immensely popular with young readers, and so it is not surprising that the records in RED are predominantly for children, not adults.

One of the earliest references to children reading the novel comes in an introduction to a collected edition of Defoe’s works edited by Sir Walter Scott, published in 1810, where he claims that Robinson Crusoe was ‘read eagerly by young people’. He put this down to the way in which Defoe’s story gripped their imagination: ‘there is hardly an elf so devoid of imagination as not to have supposed for himself a solitary island in which he could act Robinson Crusoe, were it but in the corner of the nursery’.

Scott’s claim that the novel was particularly popular with children can be backed up from other sources of evidence. In a poll of nearly 1,000 children carried out for the Daily News in 1899, where they were asked to make lists of all their favourite books, Robinson Crusoe came out on top, mentioned by no fewer than 921 of them.

However, anecdotal evidence such as Scott’s comment, and statistics like these from newspaper surveys, cannot tell us why children responded in such large numbers to this particular book, and not others. To begin to get at this kind of information, we need now to turn to study in detail the comments of individual readers as recorded in RED.

4 Female readers of Robinson Crusoe

So far, we’ve collected information on the numbers of readers of Robinson Crusoe included in RED, looking at what their ages were, and how many of them were male and how many female. In the next exercise I’ll ask you to do some work by yourself on male readers, but before that we’ll have a look together at the kinds of information we can derive about female readers of Robinson Crusoe from some of the records in RED. Since there are fewer of these than for males (only eleven in September 2010), it is possible to go through and call up each one individually.

Activity 3

Repeating the search you made using the ‘Advanced search’ facility with ‘Robinson Crusoe’ as the ‘Text being read’ and ‘female’ as the gender of the readers, please now call up all the entries for female readers of Robinson Crusoe, and make some notes on what you find out about each reader, and their reactions to the novel. Also, jot down any questions you may have, before reading further.

Comment

As you will have seen, the information in some RED records is fairly sparse. An example of this is taken from the diary kept in 1792 by the thirteen-year-old Elizabeth Wynne, while she was living in Wardeck in Austria (UK RED: 12364). All it says is: ‘I read a little of Robinson Crusoe that is how I spent my evening.’

This tells us something – a thirteen-year-old girl was reading Robinson Crusoe in the evening in 1792 while living in Austria – but we do not know in exactly what circumstances her reading took place (alone, or in company? silently or aloud?). Nor do we know what impression the book made on her. Did she enjoy it? Or did she find it boring? Again, we don’t know.

For a very different account, we might take a letter by the poet Letitia Elizabeth Landon (known as L. E. L.) in which she spoke of the imaginative power Robinson Crusoe had exerted over her in childhood:

For weeks after reading that book, I lived as if in a dream; indeed I scarcely dreamt of anything else at night. I went to sleep with the cave, its parrots and goats, floating before my closed eyes. I awakened in some rapid flight from the savages landing in their canoes. The elms in our hedges were not more familiar than the prickly shrubs which formed his palisades, and the grapes whose drooping branches made fertile the wide savannahs. (UK RED: 32079)

This gives us a marvellously vivid picture of the imaginative impact her reading of Robinson Crusoe made on the young L.E.L. – but again, we don’t know anything of the circumstances in which she was reading it. She was born in 1802, so we might suppose that she was reading Defoe’s novel some time between about 1807 at the earliest and about 1816 or 1817, but we can’t be certain.

For a third example, we might take look at the account by Alison Uttley, who was brought up on a remote farm in Derbyshire (UK RED: 2366). She recalls hearing Robinson Crusoe read aloud to the family every winter around the end of the nineteenth century. According to her, the attraction of this story above all others for her family was its connection with their own lives. Robinson Crusoe, she says:

lived a life they could understand, catching the food he ate, sowing and reaping corn, making bread, taming beasts . . . The family shared the life of Robinson Crusoe, hoping and fearing with him, experiencing his sorrows, his repentance, his setbacks . . . He read the Bible as they read it, seeking solace and help in times of trial. It was their own life, translated to another island, but still an island like their own farmland, enclosed by the woods, a self-contained community, a sanctuary.

Here we have an example of the novel being read aloud communally, as part of an annual cycle of readings – thus bringing into question assumptions that novel-reading was always something done silently and alone. But the impact of such a communal activity could evidently be as powerful and memorable as any individual reading experience.

5 Male readers of Robinson Crusoe

Activity 4

I want you now to call up records of ‘male’ readers of Robinson Crusoe, and spend some time looking in detail at nine or ten of these. You are welcome to browse for yourself, but because there are many to choose from, I’d like you to include among the ones you read UK RED: 2357, UK RED: 2358, UK RED: 2360 and UK RED: 4325. Please make some notes on what you think we can learn from these about the ‘reception’ of Defoe’s novel. In what ways, if any, do you think the responses of male readers here differ from those of the female readers we’ve been looking at? When you have done some work on this, and made your own notes, open the ‘Discussion’ box to compare your ideas with mine.

Comment

One point that strikes me is that what is remembered by many of the male readers is how reading Robinson Crusoe opened up new horizons, and inspired them to break away from their own backgrounds and circumstances. For many of these boy readers, it was, quite literally, a book that changed their lives.

So, for example, in UK RED: 2357 we learn that Joseph Greenwood, a weaver’s son, read a cheap edition of Robinson Crusoe as a child in the late 1830s: ‘To me Daniel Defoe’s book was a wonderful thing, it opened up a world of adventure, new countries and peoples, full of brightness and change; an unlimited expanse’.

Similarly, John Ward, a ploughboy who went on to become a Labour MP, remembers reading Robinson Crusoe in 1878 when he was twelve: ‘I devoured – not read, that’s too tame an expression – Robinson Crusoe, and that book gave me all my spirit of adventure, which has made me strike new ideas before old ones became antiquated, and landed me in many troubles, travels, and difficulties’ (UK RED: 2358).

Thomas Jordan describes reading Robinson Crusoe in one sitting in about 1903, when he was eleven. The book’s promise of ‘faraway places fired my imagination’ he said, and he credited it with his decision later in life to leave his job as a miner in Durham and to join the army (UK RED: 2360).

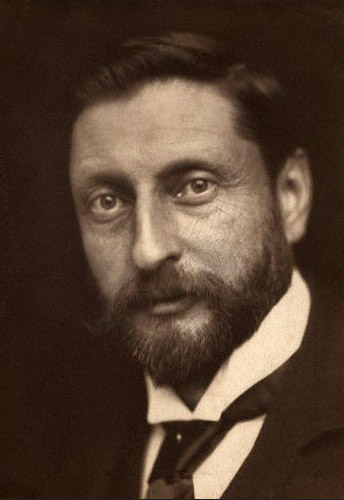

Finally, we read how H. Rider Haggard credited his own decision to become a writer of adventure books to his love of books like Robinson Crusoe as a boy (UK RED: 4325).

6 Conclusion

This case study of the reading and reception of Robinson Crusoe has focussed on children. We have seen that Defoe’s novel was immensely popular with young readers, and we’ve begun to explore some of the ways in which it apparently influenced them. It is worth remembering, however, that the book was originally written by Defoe as a book for adults, not for children. The complicated processes by which it gradually came to be regarded as a book for children and not for adults and the wider implications of this shift would themselves be worth studying.

A key moment in its critical reception was its inclusion by Rousseau in his famous educational treatise, Émile (1762) as the one book that was to be compulsory reading for the young Émile. This seems to have encouraged the notion that Robinson Crusoe was, above all, a book for children. By 1868 we find Sir Leslie Stephen, in a essay on Defoe published in the Cornhill Magazine, remarking rather condescendingly that ‘Robinson Crusoe is a book for boys rather than men . . . for the kitchen rather than for higher circles’, though adding that ‘for people who are not too proud to take a rather low order of amusement’ it will ‘always be one of the most charming of books’.

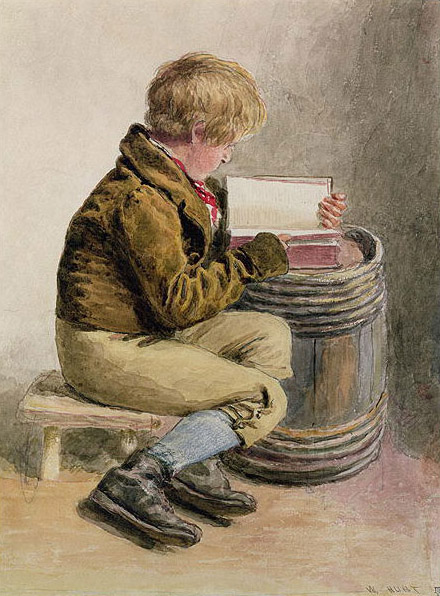

Martin Green, in his book Dreams of Adventure, Deeds of Empire (1980), has pointed out that relegation to children, which may seem like a relegation to the periphery of literature, may in fact be a shift ‘to something like the centre of culture; for the books that shape ourselves as a nation or as a class are surely the books we read as children’. The vast cultural influence of Robinson Crusoe was noted by a number of commentators in the nineteenth century. George Borrow, for example, writing in 1851, regarded it as ‘a book which has exerted over the minds of Englishmen an influence certainly greater than any other of modern times…a book, moreover, to which, from the hardy deeds which it narrates, and the spirit of strange and romantic enterprise which it tends to awaken, England owes many of her astonishing discoveries both by sea and land, and no inconsiderable part of her naval glory’. As a boy of six, Borrow said, he had been inspired to teach himself to read because he was so fascinated by the illustrations in a copy of Robinson Crusoe that he could not rest until he was able to satisfy his ‘raging curiosity with respect to the contents of the volume’.

What conclusions might we tentatively draw from this little study of male and female child readers of Robinson Crusoe? One conclusion is that evidence from UK RED seems to suggest a possible gender divide in the reception by children of this famous novel, with girls and boys taking different things from it. For girls, the attraction of the story seems to have lain in its connections with their own lives. This is a point made by Jane Gardam in her novel Crusoe’s Daughter (1985), where her lonely young heroine identifies passionately with Crusoe, seeing in his life as a castaway a resemblance to her own situation and finding his story a source of consolation. For boys, on the other hand, Defoe’s novel fired their imaginations with thoughts of travel and adventure. Might this gender divide be a feature of the ‘adventure’ genre in general? You might like to do some further work on the evidence in UK RED, tracing the reception history of other novels to see whether they exhibit a similar divide.

If you come across evidence of reading from the past that is not yet in UK RED, please do contribute your research to the project: your evidence is vital to our understanding of reading in the past. You can find information on contributing to the project, and our simple online contribution form, here.

Further reading

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Professor Bob Owens.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Course image: Jens Schott Knudsen in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Licence.

Figure 2: title-page of an eight-page chapbook version of Robinson Crusoe [c.1750] Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Gale.

Figure 3: Letitia Elizabeth Landon (1802-1838). Portrait from an original painting by Maclise, British Library

Figure 4: Little boy reading a book, by William Henry Hunt (1790-1864) © National Portrait Gallery

Figure 5: Sir (Henry) Rider Haggard by George Charles Beresford, 1902, National Portrait Gallery

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University