2.3.2 Should I wait until I’m inspired?

Sometimes, the best inspiration comes after the first line, or more likely still, after writing a few pages.

Inspiration is very often the result of habit, of getting into a rhythm of work, and of setting yourself goals of how much and about what you wish to write each day. Oddly enough, the determination that you will finish a particular piece of work is a great source of inspiration. So set yourself a realistic goal each time you sit down to write. Find out how much you are comfortable writing each day. Achieve that. Then extend it and try to double your output.

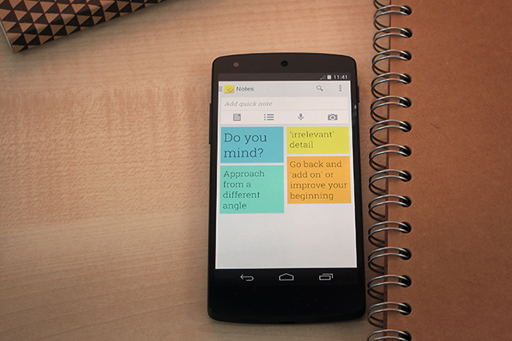

Remember: decide where you’re going before you set out. If you end up somewhere else, simply ask: do you mind? It might be a good thing to have strayed from the path. Assess this once the work is done.

Don’t wait until you have the perfect first line. In practice, it often transpires that perfect first lines no longer fit with the story once it’s written out. Instead, try to think of your opening line as being simply like a doorway that you must pass through to get into the ‘room’ of your story. The doorway is much less important than what’s inside the room – focus on that. If you find yourself ‘seeing the whole story at once’, and you’re unsure where to begin, concentrate on one particular detail and start there.

Example: You want to write about a young man and his girlfriend. He’s just realised he’s in love with her, and is going to say so, but you think that having him just saying ‘I love you’ will sound a bit flat. So, think about how else you could approach it. You could:

- begin with him trying to decide which shirt to wear

- begin when he’s stuck in conversation with someone else, and can’t get away. He has something important to say, and yet a friend is talking to him about football

- begin after the actual moment of him telling her ‘I love you’

- tell it from someone else’s point of view – for example, one of the boy’s friends, overhearing him, or the girlfriend herself.

In this way, focusing on an apparently ‘irrelevant’ detail might be the perfect way in to your story:

- a plane flying overhead as he speaks, drowning out his words

- a piece of lettuce stuck between her teeth that makes him smile

- a gang of schoolchildren who loiter close by, making him self-conscious.

Peripheral details like this can have the effect of making the scene seem more believable: real life is full of such details and delays, obstructions to the main story unfolding.