Seeing institutions in different ways

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 26 April 2024, 5:51 AM

Seeing institutions in different ways

Introduction

The central focus of development studies is how social and economic change can be achieved successfully. Critical to this success is institutional development, as it is through developments in institutions that development in the policies that drive change can be achieved. However, institutions are rich and complex phenomena, and institutional development is a rich and complex process. It is therefore possible and necessary to look at institutions from different angles and see them in different ways. This free course encourages you to do exactly that, in order to establish a base from which to think about institutional development.

This course presents you with three widely accepted ways of seeing institutions:

- Institutions as rules and norms: We will look at the differences between institutions and organisations, and how they relate to each other. The course also suggests that, if institutions are seen as rules governing social life, then it seems appropriate to view institutional development as a matter of changing the rules.

- Institutions as meanings and values: This course suggests that resistance to change can be seen as arising when and because that change has no meaning for people who are expected to accept it, or it offends their deeply-held values. Resistance thus generated can be particularly powerful and effective because so much is at stake.

- Institutions as big players: This course draws attention to the centrality of power and power relationships in institutional development, and shows how institutional development involves power struggles.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course TU872 Institutional development: Conflicts, values and meanings.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand different ways of thinking about institutions and institutional development

appreciate that institutions in processes of development create pictures of institutional landscapes

understand some of the factors that can promote or hinder institutional development

locate yourself in the institutions significant for life and work.

1 Institutions as rules and norms

Institutions frame our lives. From birth through to death, in the most private and the most public aspects of our lives, in our personal and professional histories, we are shaped by – and we in turn shape – institutions. They give structure and meaning to our lives. They make shared experience, and shared action, possible. In short, we live our lives – as social beings – through institutions.

I can put this in more formal, academic terms. Teddy Brett, who has contributed a great deal to the theory and practice of institutional development in various parts of the world over the past 50 years, talks of institutions in terms of ‘sets of rules’ (see Box 1).

Box 1 Institutions as sets of rules and norms

Institutions are sets of ‘rules that structure social interactions in particular ways’, based on knowledge ‘shared by members of the relevant community or society’ (Knight, 1992, p. 2). Compliance to those rules is enforced through known incentives or sanctions. In other words, institutions are the norms, rules, habits, customs and routines (both formal and written, or, more often, informal and internalised) which govern society at large. They influence the function, structure and behaviour of organisations – ‘groups of individuals bound by some purpose’ who come together to achieve joint objectives (North, 1990, p. 4) – as actors in society. Institutions, by producing stable, shared and commonly understood patterns of behaviour are crucial to solving the problems of collective action amongst individuals.

This is a passage that I would invite you to spend some time thinking about. It brings together so many things worth saying about institutions, all of which serve to establish the significance of institutions. Before I turn to single out and discuss two terms, ‘rules’ and ‘norms’, let me highlight some of the other important points in this passage:

- the shared knowledge that underpins institutions

- the habits, customs and routines which are also expressions of institutions

- the relationship between institutions and organisations

- the way institutions make collective action possible.

All these are points worth exploring; the last is of particular significance. However, I want to identify and answer what I take to be the central question this passage raises:

What does it mean to describe institutions as ‘rules and norms’?

1.1 Rules, norms and institutions

One way of getting at what Brett is saying is to think of the expression, ‘as a rule’. It’s a term that indicates the way in which life is expected to be conducted in particular contexts. Thus, for example, in contemporary liberal democratic societies, ‘as a rule’:

- children between particular ages go to school (the institution of education or schooling)

- leaders are elected by popular vote (the institution of democracy)

- people with insufficient income receive benefits in cash or kind (the institution of welfare)

- people have a choice as to how and from whom they obtain goods and services (the institution of the market)

- although not only characteristic of liberal democracies, wealth is distributed unequally (the institution of inequality).

Note, incidentally, that I have specified a context in which these ‘rules’ can be identified: ‘in contemporary liberal democratic societies’. Like any other social phenomena, institutions need to be seen in their particular place and time to understand the reasons for the form they take: educational institutions, for example, may be centralised or decentralised; the market may be more or less regulated.

You might want to challenge my identification of these rules, suggest that I have in one way or another got them wrong. For example, a colleague has suggested that the last institution on my list – the institution of inequality – is rather different from the preceding four:

I am not sure this is right in terms of how Brett has defined institutions. Are you saying that inequality is a norm or a rule or a set of agreed patterns of behaviour? Isn’t it an outcome of those? There are institutions that help create inequality, e.g. capitalism, taxation, ownership of property etc. Inequality is institutionalised though, which is rather different.

This is a useful challenge. It raises two important points. One is that institutions should not be seen in isolation, but rather as connected with one another, with the connections themselves making a difference. I would in this case stick with calling the ‘difference’ – the inequality – an institution, but perhaps a ‘higher-level’, overarching institution. The other – signalled by the term ‘institutionalised’ – draws attention to the fact that when we are talking about institutions and institutional development what we are talking about is ‘built-in’, part of the fabric of society: there – more or less – permanently.

The process of challenge is an important part of our exploration of institutions and institutional development. I hope you will follow my colleague’s example and question what I have to say and offer your own interpretation.

Whether or not you accept ‘my’ rules, I hope you can see that institutions in this sense – as rules – provide guidance as to what people should do, how they should behave, the paths their lives should follow. I hope you can also see that, behind the rules, there are sanctions for not complying with them.

I’ve looked at the first of the two terms, rules. What of norms? There is in fact a lot of overlap between the two terms, certainly in the sense that both rules and norms provide guidance as to how people should behave in society. Norms, though, are often seen more as beliefs about what is acceptable behaviour, views as to the qualities people should display in their social lives. So, for example, honesty, loyalty and reciprocity may be norms.

Don’t, though, be misled into thinking that norms are expressions of what constitutes ‘good’ behaviour by the list I have just presented. Corruption may be a norm, in the sense, for example, that it is expected and acceptable that bribes be offered to public servants in return for favours. Rules and norms are not in any straightforward way to be seen in terms of ‘good’ and ‘bad’.

1.2 Institutions as sets of rules and norms

Brett goes further than referring to rules and norms. He talks about ‘sets of rules’ (and by extension he might as well say ‘sets of norms’). This is important, as I indicated in relation to my colleague’s challenge. Institutions – as rules and norms – don’t exist in isolation, but rather can be seen to be connected with each other in any given society.

Douglass North is one important theorist who has promoted this idea. It can be taken too far! One of North’s followers put it like this:

Douglass North, the Nobel Laureate, made clear that institutions are the rules of the game in a society Characteristically, each rule performs a distinct function. But its effectiveness hinges on being complemented and supplemented by others. Together, the rules form a hierarchic structure of mutually supporting directives that influence jointly and can impact decisively the development of nations.

That is taking the idea of the connectedness of institutions too far. Sometimes ‘directives’ are ‘mutually supporting’, sometimes they are not. Nonetheless, rules do overlap, as is better suggested in the following statement:

Social, political and economic institutions overlap and affect each other – and they seldom relate to isolated spheres of human action and interaction. Change in one institutional sphere will impact on other institutional spheres.

This valuably suggests that when looking at institutions with a view to changing them – changing the rules and norms – you need to look for these connections. You need in fact to see the whole institutional landscape in which the change will take place.

As Brett indicates, the rules and norms are not necessarily written down: norms very rarely are. Some rules will be, but in all these cases – and in any others – written rules will be complemented with unwritten ones, and those unwritten rules can be the ones that act most powerfully on us as ‘incentives or sanctions’.

And, of course, different people will interpret the rules in different ways – and some will break them or work outside them.

You might like to think about and comment on these last two points, perhaps in the light of the (I think) useful idea I cited above of institutions as the ‘rules of the game’. But now I want to pick up another key point raised in the statement from Brett: the relationship between ‘institutions’ and ‘organisations’.

1.3 ‘Institutions’ and ‘organisations’

Brett sees institutions in terms of rules and norms. But his central concern is not to define institutions, but rather to establish their significance. To do this, amongst other things, he distinguishes between institutions and organisations.

Brett describes organisations as ‘actors in society’. Organisations get things done or, to follow the metaphor, they act, they perform. By contrast, institutions provide the framework in which the performance occurs. Thus, for example:

- schools teach children, within the framework of the institution of education

- political parties seek votes, within the framework of the institution of democracy

- public and voluntary agencies provide benefits, within the framework of the institution of welfare

- supermarkets and other shops compete to provide goods, within the framework of the institution of the market

- companies give different financial rewards to different employees, within the framework of the institution of inequality.

And, of course, some organisations will perform better than others, and, as with people, some will act outside the institutional framework – and will sometimes break the rules.

Is the difference clear-cut?

In an everyday sense, the short answer is, ‘no’. As you will probably already appreciate, there is a considerable overlap between institutions and organisations. Organisations can become institutions as they become established and recognised as standing for something more than themselves; they come to embody and express important social norms and values.

This can perhaps be seen most obviously in a global context, with organisations such as the World Bank or the United Nations. But it is no less true at a local level where, for example, a school can come to be recognised as having a significance far beyond its own gates, or a shop can come to be seen as a place not just where buying and selling take place but also where key neighbourhood concerns are identified and expressed.

But the question can be answered in a rather different, and no less important, way: with an answer perhaps closer to a ‘yes’. We can look at precisely the same social entity – the school you attended, for example, the agency you work for – though two different lenses: an organisational lens and an institutional lens.

With the organisational lens, in the case of your school, you might be looking at, say, the range of classes in the school, the different ways in which teaching takes place in different classes. With the institutional lens, you might be looking at the wider ‘rules’ which, for example, require schools to arrange classes by age or by ability.

With the organisational lens, in the case of your agency, you might be looking at, say, your work on a poverty reduction programme. With the institutional lens, you might be looking at, the wider ‘rules’ which, for example, require that your agency works in ‘partnership’ with other agencies.

In the latter case, note that what I am calling the ‘rules’ might be set down in the tendering procedures, setting the terms on which your agency can participate in the programme. They might, equally, take the form of a less formal – but no less binding – understanding that ‘this is how we do development’.

My particular interest in this course is in the institutional lens, because that is the one that is focused on the rules and norms, formal and informal, that guide our behaviour and the behaviour of our organisations. This is not, though, to deny the value of the organisational lens – which, amongst other things, focuses on how the rules are interpreted and put into practice.

1.4 Institutions as rules and norms in your life and in development

In this section you will explore the ideas of rules and norms so far discussed in relation to your own experience and in relation to development. Activity 1 gives you an opportunity to connect your own experience and understanding with this first way of seeing institutions, as rules and norms.

Activity 1 Institutions as rules and norms in your life

Using Brett’s definition of institutions in Box 1 and my subsequent commentary on it, identify and make a few notes on some of the institutions that have ‘framed’ your life. As you do so, think about how Brett suggests that institutions ‘structure social interactions’, ‘govern society at large’ and contribute to ‘solving the problems of collective action’; and about the ‘stable, shared and commonly understood patterns of behaviour’ that he says institutions produce. Think also about the differences between institutions and organisations, and how you would define and illustrate those differences.

Think in particular about the ‘rules’ you are expected to observe, and about the norms that set expectations as to how you should behave.

Make these notes before you read the discussion below, and then compare your notes with that discussion.

Discussion

Whilst there is a long list to choose from, you may possibly have thought of the family, schooling, faith, university, the state, law, democracy (or some other political system), or the market. Whatever you have chosen, though, it is likely that you will have chosen them because – using different means to enforce the ‘compliance’ that Brett speaks of – they will have governed your relations with other people in particular contexts and in society at large. They will have set the rules you were expected to follow.

You may well also have chosen them because you are aware they have given you a sense of who you are, have enabled you to understand the world you live in and your place in that world. That is important, too, and anticipates a second way of seeing institutions that we will shortly be exploring: institutions as conveyors of meaning and meaningfulness, and as expressing values. The point to make now is that it is a good thing to be seeing different qualities of institutions, seeing that they contribute in many more ways than one to our social life. They are not just rules.

You may have found distinguishing between institutions and organisations problematic – in which case it may be useful to reinforce the three points I made in introducing the distinction:

- Brett’s key concern is to identify organisations as ‘actors in society’. (He is not, incidentally, dismissing the idea that individuals also are actors.) Institutions provide the framework within which organisations (and individuals) act and the rules which guide their actions. Note, though, that – to follow the acting metaphor – institutions do not write or provide the script for the actors.

- It is entirely appropriate to talk of particular social entities as both institutions and organisations. But more generally, there will be an institutional dimension to any organisation, simply because in the nature of social life it will embody and express certain rules that have an existence and significance beyond its own boundaries.

- Perhaps most importantly, you can use both an organisational lens and an institutional lens to investigate any social entity. I will focus on the latter, but that is not to dismiss the value of the former.

You can use these points as you turn now to look at the world of development through an institutional lens.

Activity 2 Institutions as rules and norms in development

Identify some of the institutions that frame development, and then make notes on how their ‘rules and norms’ have an impact on development.

You might for the purposes of this activity use your own understanding of development, or perhaps an understanding of development derived from the economist, Amartya Sen (1999), who sees development as the expansion of human freedoms. In either case, this can be seen both as:

- a long-term, uneven and contradictory, historical process involving the expansion of these freedoms, and as

- deliberate interventions intended to bring about the expansion of particular human freedoms.

Draw on your own experience. Remember that whether you are professionally involved in development or not, you are caught up in development of some kind.

Discussion

Development, too, is framed by a variety of institutions. You might have thought of some of the large institutions, such as the World Bank and the United Nations, which are ‘big players’ on the world stage. You might have thought of micro-finance, of workers’ associations, of NGOs (Non Government Organisations), of development ‘partnerships’, of free trade, of civil society. You might have thought of smaller, more local, institutions where you live and/or work – for example, a forum which provides a framework for agencies working on educational issues. In all cases, these institutions will in some way or another set the rules which govern joint action for development, and express the norms which indicate behaviour that is acceptable and behaviour that is not.

The institutions that you identify will almost certainly be different from institutions that other students identify. The specific institutions that contribute, say, to the improvement of health services in the UK are different from the institutions that contribute to the reduction of poverty in the Indian sub-continent, which in turn are different from the institutions designed to create liberal capitalism in eastern Europe, or those set up to address problems related to HIV/AIDS in southern Africa, and so on.

It is worth noting, though, that such is the sway of ‘globalisation’ that similarities can be identified between institutional development in very different contexts: so, for example, one finds similar institutions of partnership, social enterprise, participation and governance being developed for urban regeneration in the UK as for rural development in Uganda. The rules have to do with the same issues – accountability, transparency, for example – though they are expressed in different ways in different contexts.

It is possible that your choice reflected an institution’s significance not only in shaping how development takes place, but also in framing how development is conceptualised. It is particularly important to recognise that there are institutions which govern how development is seen. Perhaps the most obvious example is one to which I have already made passing reference. Current development discourse expects development – ‘as a rule’ – to take the form of ‘partnership’ between agencies.

Whatever your choices, whether or not you are a ‘development manager’, you should by now be aware that you have a wealth of experience of institutions – as rules and rule setters, and indeed much else.

1.5 Institutional development: changing the rules, the rules changing

As you undertook Activity 2, you might have noted that institutions last: they have a seeming permanence to them. Brett uses the term ‘stable’, others say that institutions ‘persist over time’ (Uphoff, 1986, p. 9). That is the nature of institutions: they are around for a long time – it is one of their defining qualities. Yet institutions are not ‘forever’. Or, to use one of the concepts I have set out with, the ‘rules’ do change.

However stable they might seem, institutions are constantly changing. They come into being, mature, change – and they usually, if not always, come to an end. Their historical rise, decline and fall can be traced – though in some cases the perspective has to be exceedingly long term.

The nation-state is one of the most obvious examples. Emerging in – let’s say for the sake of the argument – the 17th century in western Europe, the nation-state came to be the dominant institutional form for framing both societies and the relationships between societies. In the 21st century that period of unqualified dominance has ended: the rule no longer holds good.

A variety of other institutions, supra-national ones – such as the European Union, G8, the World Trade Organisation, transnational corporations, to name only some of the more obvious – are increasingly dominant. At the same time, intra-national institutions – often, though by no means exclusively, built around ethnic or national identity – have challenged the right of the state to govern all the people within a particular geographical territory.

Even in the cases of institutions which seem to go on forever – the family and faith are perhaps the most significant examples – the form of the institution, the relationships involved, the norms and values embedded, the rules, differ so markedly that they constitute different institutions at different times and in different places. Certainly there is continuity, no less certainly there is change.

It is clearly possible and useful, as suggested by the terms just used – ‘created’, etc. – to think of change as coming about as a result of deliberate action: the change is intended. It is equally possible and useful to think of change as emerging – in a way no one exactly intended – out of the complex of social interactions that make up history.

This distinction between the more and less intentional processes is of importance for our understanding of institutional development. So take, for example, the emergence of the labour movement in the UK as an illustration of institutional development in its more and less intentional aspects. It is clear that groups of women and men came together to establish specific bodies that together made up the labour movement: they intended to change their working lives for the better by this means.

But this does not tell the whole story. These actions were not taken in isolation. They connected with the actions of many more people, pursuing their own particular and different purposes. And all were caught up in a range of complex processes, not just that one leading to the emergence of the labour movement: the development of new technologies, the establishment of factories that the technologies made possible, the consequent rural–urban migration, the emergence of large urban settlements. These were certainly not intended to bring about the labour movement. Yet the deliberate actions that created the labour movement were made possible and shaped by those processes, which were, in turn, shaped by the deliberate actions that established the labour movement.

Much the same argument could be made about the emergence, say, of liberation movements in the colonised world, of the movement for women’s emancipation, of the anti-globalisation campaign, of the movement to secure human rights in the face of massive abuse. All have been created through the purposive, value-oriented action of individuals and groups, often in the face of great personal danger. Equally, all have involved interactions between a range of actors with differing values, interests and agendas. And all have arisen in the context of broader social and economic processes – most obviously to do with changes in labour markets – which certainly have not been intended to bring about these specific developments.

It would be wrong to think that these are two different and separate processes – the intentional and the unintentional. As I have tried to convey, they are intimately bound up with each other, in real life inseparable. Nonetheless, there is value – as in my discussion of institutions and organisations – in thinking of and using two different lenses: one lens as ‘institutional development as intervention’, where the focus is on intentional activity, and the other lens as ‘institutional development as history’, where the focus is on a long process of interactions between diverse actors, a process which at any given point provides the context that determines the scope and potential for interventions.

Note that both lenses enable us to examine and explain changes in Brett’s ‘rules that structure social interactions’.

1.6 A story of changing the rules

I said earlier, introducing the idea of institutions as ‘rules’, that ‘different people will interpret the rules in different ways – and some will break them or work outside them.’ ‘Breaking the rules’ is one way of thinking about institutional development.

The story you are about to read is a story about, amongst other things, ‘breaking the rules’, and thus a story about institutional development. It is a story that many years after I first read it I still find exhilarating, still find a source of insights into institutional development. It is – as are all stories – a partial story, a story told by and from the perspective of one person inside the story, indeed one of the creators of the story. It is, as will be evident from the very opening words, a story about him as well as a story about institutional development.

For me, this individual perspective heightens the value of the story, partly because it reminds me that institutional development depends on individual agency, and partly because it leaves me very aware that other stories could be told, by people with different experiences of this process of institutional development, and I can try to imagine those stories.

But on to the story! It’s the story of the creation of BancoSol, a Bolivian micro-finance agency, as told by Pancho Otero, one of the founders of this ‘solidarity bank’.

Activity 3 BancoSol case study

Read Otero (1997). It is a story of institutional development aimed at poverty reduction. It is based on presentations given by Pancho Otero, one of the founders of BancoSol, when he was a visiting speaker at a conference on micro-finance in Harare, Zimbabwe in January 1997.

I find that this is a story that is worth reading quickly to start with – to get a sense of the ‘fantastic adventure’ that Otero describes – and then going back and reading it again, more slowly, to analyse what he is saying, to pick up the many insights he offers into institutional development.

However you read it, at some point make notes in answer to the following questions:

- What are the two significant changes – processes of institutional development – that Otero presents?

- What are the ‘rules’ that get broken in both processes of institutional development?

- What is the ‘philosophy’ of BancoSol, and why was it important?

- What is Otero referring to when he talks about the ‘institutional culture’ of BancoSol? How was it created? What was its role?

- How does Otero account for the success of BancoSol?

Discussion

Whilst this account can be read as one story: the history of BancoSol, it is clear that there are two distinct processes of institutional development:

- one which challenged the rules of banking in Bolivia in the 1980s, and

- a second which challenged and changed the rules with respect to how a micro-finance agency should operate.

Changes and challenges to rules

Otero uses the term ‘fantastic adventure’ to describe both the creation of a micro-finance agency and the ‘transformation’ of this new institution, its ‘transition’ into a bank.

In the first case, the fundamental rule of banking that was being challenged was: Don’t lend to the poor! Strongly related to this was the rule: Show the poor no respect! Otero mocks both these rules; BancoSol broke them.

In the second case, the fundamental rule being challenged might perhaps be described as: Don’t mix development enterprises with commercial approaches! Otero was clearly disturbed by what he was doing in calling this rule into question: ‘this is what shook all my understanding of development, it made me have a fever, and I had to rethink everything I had thought. This was earth shattering, this was truly a major milestone for me personally and a major milestone for the Institution’ (p. 61).

This is a sharp statement of the nature and impact of institutional development! So it perhaps comes as something of an anticlimax when – pointing to another quality of institutional development – he goes on to say: ‘So after the fever went down and after we thought about this for a few days we sat with the major staff and talked about this. Little by little it started to make sense’ (Otero, 1997, p. 61). That itself offers another insight into the nature of institutional development: the incremental way in which often it comes about, the time it takes for it to ‘make sense’.

Philosophy and culture

Otero sets out the bank’s philosophy: ‘a small philosophy we had, we called it the four f's – fast, friendly, focused and flexible’ (Otero, 1997, p. 52). The philosophy was important because it provided the principles by which the operation was guided. It was also important in that it set out the founders’ world-view, and in particular their view of development:

At home we saw development as not the big road from Bulawayo to Limpopo or something, not the big electrical dam; development is when in every household everyone is working and everyone is productive, so we put development into the back yard of the houses.

This philosophy, this set of principles, formed part of a much wider ‘institutional culture’. ‘Culture’ includes all the values, meanings, norms, principles and practices which give an institution – or any group of people – its identity and which enable people within that institution to make sense of the world and of the relationships in which they are caught up. Central to the BancoSol culture was the value BancoSol placed on its clients. Indeed, it was the decision to treat poor people as clients that distinguished BancoSol from established banking institutions:

Friendly meant that we were not going to be any of the extremes to the client, we were not going to be paternalistic and we were not going to be stonefaced as personal bankers, because in Bolivia up until then they only had those two things. ... There were all those names for them which were completely degrading, basket cases, the poor and vendor women. Of course, the bankers were calling them riff raff, so we came up with a great invention, we called them clients, we called the peasant women customers and this was extremely important. So friendly meant something other than just smiling. Behind this word there was a lot of respect for the client.

Success

This ‘great invention’ – this overturning of what happened ‘as a rule’ in Bolivian banking – was, in Otero’s view, at the heart of the success of this process of change:

If you just do the financial part it is not going to be successful, our clients are marginalized and are mistreated everywhere they go, in the bus, at the police station, at the grocery store, everywhere they are looked down upon. So if you have an institution that has a lot of respect for them, but not paternalistic, then you will have success.

That is not the only reading possible of Otero’s story of BancoSol. I trust, though, that you find it a convincing and useful one and that, together with your own reading, it has helped you develop a sense of what institutional development might involve.

1.7 Looking at BancoSol through a different lens

I suggested that Otero was using an ‘institutional development as intervention’ lens when looking at BancoSol’s history. I want to conclude my account of BancoSol by briefly looking through the other, ‘institutional development as history’, lens.

Otero provides a story of action from the point of view of the activist. What we don’t get is a proper sense of the context in which that action was taken, the history it becomes part of. The ‘history’ lens enables us to do this. The following brief extract from a paper on the development of micro-finance illustrates what I mean:

The Bolivian intervention [BancoSol] displays: brilliant dedicated individuals, country-specific economic, social and intellectual conditions, and the constant pressure of international thought and fashion. ... In the mid 1980s Bolivian economics and politics were changing quickly. A failing socialist regime was giving up its ownership of industry and liberalising the economy. This brought, on the one hand, a welcome end to hyperinflation and on the other massive unemployment ... A wave of unemployed people flooded into the towns looking for employment, but, not finding it, settled for self-employment, causing a ballooning of the informal sector. The streets of La Paz and other towns were packed with street vendors and small-scale producers, all hungry for capital.

The micro-credit idea had already reached Bolivia in various ways, including the influence of expatriate Bolivians living in the United States and, crucially, through American ODA (USAID), which had already carried out several micro-credit experiments in Bolivia.

It doesn’t take away from the brilliance of the ‘dedicated individuals’ to recognise that they were operating within a historical context which provided opportunities which they were able to exploit. Nor, of course, does it detract from the significance of their breaking of the rules of Bolivian banking.

2 Institutions as shared meanings and values

I have chosen to make use of the concepts of ‘rules’ and ‘norms’ as my first way of seeing institutions, thus making it possible to see institutional development as a process that involves changing the rules, or even breaking them (and, I should say, going against established norms and creating new norms). The BancoSol story, as I’ve suggested, can certainly be seen in these terms.

It is, however, possible to read it in a different, though not contradictory, way. You may have noticed the attention Otero – and I – paid to the cultural dimension, where ‘cultural’ is taken to refer to all those things – values, meanings, norms, principles and practices – that give people a sense of identity and enable them to make sense of the world and their place within it. It is this dimension to which I’m turning for my second way of seeing institutions, as conveyors of meanings and values.

Early on in his first workshop talk, Pancho Otero makes an interesting comment that is both confession and affirmation:

... none of us had any idea of banking or finances or supervision of banking systems. We had no idea of this but what we did have, as a common characteristic, is that we were all aware of what the clients were like.

A couple of social workers, a couple of renegade communists, a couple of ex-priests – that was the group. No finance, no calculators, none of this but we all had a nice feel for the clients.

And you may recall that in his third workshop talk, having described the ‘fever’ brought about by his realisation of the scale of the ‘transformation’ he was envisaging, he says that ‘after the fever went down and after we thought about this for a few days we sat with the major staff and talked about this. Little by little it started to make sense’ (Otero, 1997, p. 61).

The idea of ‘making sense’ is fundamental to institutional development to enable wider developmental change to occur.. The change must make sense to those caught up in it, be they clients, development managers, sponsors, or whomsoever. Put in other words, the change must be meaningful and of value to those who experience it, whether as instigators or as ‘beneficiaries’. This in turn requires that it engages with the meanings through which they live and understand their lives. It also requires it to correspond with the values by which people live their lives, their sense of what is good and what is bad, what is right and what is wrong. Only then will the change be seen as legitimate.

This idea of institutions as conveyors of shared meanings and values takes us back to the initial definition of institutions in Box 1. In order to behave according to spoken or unspoken ‘rules’, their meaning has to be understood, individually and collectively.

The reality of institutional development, though, is typically that meanings and values are not shared by all those involved in it, as is emphasised in the following preface to another story of institutional development.

Activity 4 Seeing another side of institutions

Read the extract in Box 2 from an article by Lars Engberg-Pedersen (1997) entitled ‘Institutional contradictions in rural development’, part of the introduction that presents Engberg-Pedersen’s way of seeing institutions and institutional development.

As you read it, make notes of your answers to the following questions:

- How does Engberg-Pedersen extend your understanding of institutions?

- What insights does he offer into institutional development?

Box 2 Institutions as ways of ordering reality

Rural communities are often regarded as workable objects in need of development interventions by projects, NGOs and the state. With respect to natural resource management in particular, it is commonly argued that existing farming practices are inadequate, even destructive, and should be changed. There are, however, reasons for scepticism as to how workable rural communities are. Vested interests connected to the existing social and material organisation of the communities are likely to prevent drastic changes, and so are local institutions understood as rules and shared meanings.

There are two sides to institutions. They support the distribution of rights and duties, political authority and economic opportunities. Accordingly, institutions affect actors’ strategies and their ability to pursue them. But institutions also contribute to shaping people’s understanding of social meaning and order. Actions acquire meaning and legitimacy when they comply with specific institutions. If new procedures are introduced and profound changes which shatter people’s perceptions occur, these changes might be resisted or modified. ...

Institutions must be conceptualised ‘as simultaneously material and ideal, systems of signs and symbols, rational and trans-rational. Institutions are supra-organisational patterns of human activity by which individuals and organisations produce and reproduce their material subsistence and organise time and space. They are also symbolic systems, ways of ordering reality and thereby rendering experience of time and space meaningful’ (Friedland and Alford, 1991, p. 243).

Accordingly, institutions should not be viewed as external constraints to actors who conceive strategies to manoeuvre between institutional limitations. By organising social life, institutions give meaning to action. Activities in correspondence with institutions are understandable to others, locating the actor in a particular symbolic order and thereby contributing to the actor’s self-understanding as well.

However, institutions do not determine social processes; actors may consider institutional elements critically. When an actor chooses to engage in action which confronts or bypasses a specific institutional element, this can form part of self-understanding. So, in arguing that preferences and strategies are devised on the basis of existing sets of institutions, this does not imply that actors are cultural dopes incapable of reflecting on the institutional context. ...

We can now understand development interventions as more than attempts to correct institutions that supply ‘perverse’ incentives or arenas of social struggle where different actors manoeuvre to gain access to resources. Each intervention is also a more or less deliberate attempts to establish a particular symbolic order, and each interacts with people whose strategies sometimes reflect substantially different institutional logic. Interventions seeking to change prevalent practices, therefore, have a symbolic aspect in addition to their more immediate material objectives and context.

Discussion

In this extract, Engberg-Pedersen emphasises that institutions, as well as constituting rules that govern rights and responsibilities, also ‘contribute to shaping people’s understanding of social meaning and order’. They are shared meanings and values, which help people make sense of their world, their lives and their relationships: put them all in good order.

He puts this more formally in the words of two other theorists, Friedland and Alford, who describe institutions as (amongst other things) ‘symbolic systems, ways of ordering reality and thereby rendering experience of time and space meaningful’ (1991, p. 243). I would add that the meaningfulness is for those who share the symbols, and not for those who don’t.

What do they mean? They are talking of the pictures we have in our minds through which we see the world. We have many such pictures. One particularly strong one is the picture of a world in which people fit into a hierarchy, with ‘more important’ people at the top. Another is the picture of a world made up of ‘us and them’, who might be ‘women and men’, or ‘my people and the rest’, or ‘my village and the next’.

These pictures show, or tell, us not only

- this is how it is

but also

- this is how it should be.

Drawing attention to this symbolic aspect of institutions offers a profoundly valuable contribution to our understanding of why institutional development is not easy to bring about. If change doesn’t make sense to the people caught up in it, if it isn’t meaningful, and, no less significantly, if it doesn’t seem right, the chances of its being carried through successfully – or in the way intended – are remote. Or, put another way, if the change contradicts the picture of the world that people have in mind – for example, by showing all people as equally important – it may well be seen as wrong.

This points to a particularly important lesson with respect to institutional development: ‘If new procedures are introduced and profound changes which shatter people’s perceptions occur, these changes might be resisted or modified ...’ (Engberg-Pedersen, 1997, p. 184). It is a lesson that ought to be obvious, but seems not to be, given the extent to which it is ignored. People still seek to bring in change that ‘doesn’t seem right’.

I might have drawn the extract to a close at that point. However, the subsequent three paragraphs introduce another line of thinking that has a bearing on my exploration of institutional development. Interested in change, Engberg-Pedersen finds his own way of resolving the tension – in academic, particularly sociological, circles – between ‘structure’ and ‘action’ as ways of explaining how change is brought about.

2.1 Structure and action

Sociologists have long struggled with what it is that influences and determines the way people behave. To simplify matters enormously, I can say there are two basic approaches:

- the ‘structural’ approach, which holds that social structures – such as the family we are born into, the schools we go to, the political parties available for us to join, the jobs market, the media – which are just ‘there’, determine people’s actions; and

- the ‘action’ approach, which holds that people interpret the world, internalise it and endlessly remake it – making choices, acting on the structures, and thereby changing them.

The two views are not separate or oppositional (though, in the history of sociology, there has been fierce debate between them). Engberg-Pedersen argues that whilst institutions – which, as you will gather, can be seen as structures – give meaning to action they ‘should not be viewed as external constraints’ on social actors. They do not determine in any absolute sense how people behave. Actors are not ‘cultural dopes’: they have the capacity to reflect on the institutional context and act on the basis of their reflections.

This is a premise that informs our approach to institutional development. But we take it a step further. Not only do people – more specifically, development managers – have the capacity to reflect on the institutional context, they have an obligation to do so. This is a necessary contribution to institutional development.

3 Institutions as ‘big players’

There is one way of seeing institutions that demonstrates the value of holding together an ‘action’ approach and a ‘structural’ approach to understanding social behaviour and change.

When talking of, in particular, international development we often make reference to agencies such as the World Bank, the United Nations, the World Trade Organisation, the African Union, the European Union, the Economic Commission for Latin America, national governments, to give just a few of the most obvious examples: the ‘big players’. Their size, their bigness, is important: they dominate the worlds of development in ways that other agencies cannot match, and this invests their action with great significance. Note, though, that these agencies can also be seen as institutions in the ways I have already discussed: they set the rules for development, they provide frameworks of meaning – structures – within which they expect other actors to negotiate.

Another way of recognising the significance of the big players is to suggest they establish the ‘dominant orthodoxy’ of development. What does this term mean?

It refers to the key norms and values, the accepted principles and practices, through which development is undertaken. The content of the dominant orthodoxy changes over time. Today we might talk about a ‘prevailing growth-centred vision’ (Korten, 1990, p. 4), the value attached to ‘market forces’ and privatisation, the central role ascribed to ‘good governance’, the reframing of the state as an ‘enabler’, and the focus on partnership building and the participation of diverse stakeholders in the planning and implementation of interventions. We would certainly recognise the central role played by the Millennium Development Goals in current development discourse – perhaps more in the north than the south.

It is important not to overstate the bigness, the dominance, of these institutions and to recognise that, even if they establish the framework within which development is to take place, other actors have or create room for manoeuvre within that framework. It is also important to recognise that the dominant orthodoxy is an arena of constant struggle, as individuals and agencies challenge the dominant norms and values, work outside the dominant principles and practices. As a consequence, the dominant orthodoxy itself undergoes constant change. Nonetheless, the big players feature largely in the institutional landscape of development.

Activity 5 Identifying the big players

David Hulme, a British development theorist, paints a vivid picture of this landscape, part of which is reproduced in Box 3. Look at this, and identify the main features of his picture. From your own experience, extend this picture, adding to the global picture and adding in big players – and how they operate – at other levels, for example, national and local.

Box 3 The institutional landscape for attacking global poverty

The institutional landscape for tackling global poverty is a vast terrain which lacks clear boundaries and involves a web of multilateral, national, sub-national and local institutions spread across the public sector, private business and civil society. It is also a dynamic landscape comprised of institutions reflecting the power structures and principles of different eras. While several of the key institutions date back to the founding of the UN and Bretton Woods Institutions (BWIs) in the 1940s there are many new institutions based on 21st century international power relations, such as the G20, and complex public–private partnerships, such as the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. There are many ambiguities about the roles of different institutions and their overlapping mandates. While the assumption underpinning the UN institutions is of unquestioned state sovereignty, with wise men negotiating compromises between well-articulated national interests, contemporary practices of deliberation, decision-making and practical action on global poverty have increasingly been influenced by the growing number, and increasing influence, of non-state actors. These different institutions have differing interests and visions of ‘what should be done’ and coalesce into a variety of formal and informal associations and networks.

From the outset it must be understood that the institutions, associations and networks examined here are not elements of a rationally designed international institutional architecture. Their roles, responsibilities and authorities are often unclear and they overlap, sometimes in ill-defined ways. While some are mandated to eradicate poverty around the world, others have taken on poverty reduction as an additional goal to a pre-existing mission. Policies, plans and actions occur on both a coordinated and uncoordinated basis and involve different sets of players in multiple arenas. As for other global issues – such as food supply, climate change and financial sector regulation – there is no over-arching or agreed institutional authority and, as a result, no-one is in charge of global poverty eradication.

The values that underpin international efforts to tackle global poverty, and the policies and actions that are pursued, are constrained – some would say are undermined – by the day-to-day realities of power politics in international relations. While the most powerful nations can agree that the contemporary architecture, the UN and the BWIs, is inadequate, agreeing changes has proved difficult. The most important institutions were designed to meet the needs and serve the interests of the power structure of the mid-20th century. Reforming them to recognise the configuration of economic and military power in the early 21st century remains a work in progress. The acronyms of many new organisations litter this chapter – the G20 (a recognition that no longer are there a mere handful of industrial powers), GAVI (the Global Alliance for Vaccination and Immunisation – a recognition of the significance of the commercial and non-profit sectors) and others. While both the old and the new institutions and associations are commonly identified as having specific policies and interests, it is important to recognise how porous their boundaries and positions are. For example, radical critics of the World Bank present it as a monolithic organisation with all its departments and staff determinedly pursuing a clear mission and set of policies to neo-liberalise the world. In reality the Bank is more complex, with departments set against each other and staff networking with ‘like-minded’ people in other institutions – sometimes to challenge or oppose Bank policies and actions. Forms of influence that are not focused on specific institutions – such as the epistemic community of ‘Chicago economists’ spread throughout the BWIs and ministries of finance and universities around the world – have been and can be very powerful.

Discussion

I find this an immensely rich picture, the kind of picture to which one can return time and again and find new details and new insights. Four things strike me in particular:

- Hulme conveys the dynamic complexity of this institutional landscape. Not only is it made up of many different and differing actors – from the public sector, private business and civil society – at any one point in time, it is also constantly changing. It reflects and represents interests that emerged at different points in time, and ‘remains work in progress’. It’s useful to think of it as being an emergent landscape – always.

- The extract is full of terms that remind us that agencies do not undertake development on their own, but rather in relationships with other players. Terms such as ‘web’, ‘associations’, ‘networks’, ‘configuration’ point to a collaborative – although certainly not necessarily a conflict-free – process.

- Though not using the word, Hulme presents a picture that could well be viewed using the two ‘lenses’ I talked about earlier. Of course, agencies look to identify and pursue particular courses of action: the lens of ‘institutional development as intervention’. But Hulme is careful to point out that the agencies are ‘not elements of a rationally designed international institutional architecture’ (Hulme, 2010, p. 81–2). What they do emerges from a long and continuing series of interactions, some complementary, some contradictory: the lens of ‘institutional development as history’.

- Perhaps most strikingly, the picture is one of power plays and politics. I’m not sure that I agree with Hulme’s formulation in this respect: ‘The values that underpin international efforts to tackle global poverty, and the policies and actions that are pursued, are constrained – some would say undermined – by the day-to-day realities of power politics in international relations’ (p. 82). ‘Constrained’ and, even more, ‘undermined’ reflect a negative view of politics – or at least of ‘power politics’. It might be better to say simply that ‘power politics’ are unavoidable, a part of the reality that development managers must negotiate. That reservation aside, I entirely agree with Hulme in his wider concern to put power and politics at the heart of the particular process of institutional development – that of poverty eradication – that he is exploring.

So for me it seems entirely appropriate, necessary even, to conclude this opening look at ways of seeing institutions and institutional development by affirming the centrality of power.

3.1 Power

‘Power’ is a concept without which institutions as sets of rules and norms cannot be properly understood: power to make the rules, power to question and break them, power to establish the norms. The same point can be made about institutions as sets of meanings and values: the power to bring in new meanings, the power conferred by meaning to resist such interventions, the power to establish what is right and – no less critically – what is wrong. And, as Hulme shows, it is a concept without which we cannot see and understand the actions and interactions of the big players.

The picture presented in Box 4 will give you a sense of the way in which power – interestingly (and unusually) as a process rather than something people possess – works:

Box 4 Power

Like knowledge, power is not simply possessed, accumulated and unproblematically exercised. ... Power implies much more than how hierarchies and hegemonic control demarcate social positions and opportunities, and restrict access to resources. It is the outcome of complex struggles and negotiations over authority, status, reputation and resources, and necessitates the enrolment of networks of actors and constituencies. ... Such struggles are founded upon the extent to which specific actors perceive themselves capable of manoeuvring within particular situations and developing effective strategies for doing so. Creating room for manoeuvre implies a degree of consent, a degree of negotiation and thus a degree of power, as manifested in the possibility of exerting some control, prerogative, authority and capacity for action, be it front-stage or back-stage, for flickering moments or for more sustained periods. ... Thus, as Scott (1985) points out, power inevitably generates resistance, accommodation and strategic compliance as regular components of the politics of everyday life.

In its own way – it is highly abstract – this is as rich a picture as that offered by Hulme, one that will help you appreciate the politics of institutional development.

4 Extending ways of seeing institutions

I have suggested three ways of looking at institutions:

- as sets of rules and norms, that govern how people behave and how organisations operate, and that make it possible for agents with different interests, world-views and agendas to work together for development (Brett)

- as conveyors of shared meanings and values, that enable people to make sense of their world and identify what is acceptable, and legitimate, or not (Engberg-Pedersen)

- as big players, that are influential in establishing the terms on which development is to take place (Hulme).

This suggests in turn that institutional development can be seen as, amongst other things:

- changes in the rules, attempts to bring in new rules, attempts to make the old rules more appropriate, challenges to the old rules, shifts in social norms

- the emergence and acceptance of new sets of meanings, attempts to reinforce established meanings, challenges to established meanings, the promotion of new values

- the introduction of new policies and programmes to ‘deliver’ development, the emergence of new big players, the creation of new alliances between big players, challenges to the power and authority of the established big players.

Activity 6

Check your understanding of the following key concepts by thinking of examples of each of them.

- rules: governing who can participate in a development intervention

- norms: setting standards of acceptable behaviour on the part of agency workers

- meanings: giving a sense of what it means to be ‘poor’, to live in ‘poverty’

- values: establishing what would constitute ‘good’ impacts of interventions

- big players: international agencies, national governments, national forums, local coordinating agencies.

You might put your examples together in a simple spray diagram, or mind map. These concepts do not represent alternative – let alone conflicting – views of ‘institutions’ and ‘institutional development’. Rather, all identify dimensions that you need to keep in mind as you develop your understanding of each of these two terms.

I do, though, want to emphasise that it is essential not only to recognise these concepts, but also to ask questions about them – interrogate them, if you like.

4.1 Questioning institutions and institutional development

Whilst encouraging you to develop your own sets of questions, I would also encourage you to make use of a set of questions that have – for quite obvious reasons – been labelled the ‘five Ws and H’ and that are used as a formal technique for exploring social processes, including the way those processes are thought about. The five Ws and H are: What? Who? Where? When? Why? and How?

Like any technique, the five Ws and H is neither perfect nor all-sufficient. You may find your own set of questions better. Or you may think that, for example, a stakeholder analysis is needed to address fully the ‘Who’ question and bring out the interests involved more effectively.

The technique does, though, provide one means of interrogating particular processes in a relatively structured, systematic fashion. And in its simplicity it can generate ‘awkward questions’, questions that get under the surface of a process or way of thinking, questions that expose the reality underneath the surface.

Applied to institutional development as we have been viewing it they might include:

- What are the rules? What vision of development is driving the process? What interests are being promoted?

- Who is setting the rules? Who is challenging them? Whose values are evident in the process?

- Where are the norms expressed, formally and informally? Where is the motivation coming from? Where do these players get together?

- When did these rules begin to seem dated? When did people begin to think differently about this issue? When did these players start getting together?

- Why have these rules emerged? Why has it made sense to think differently about this issue? Why did these players get together?

- How are the rules being enforced? How have people been encouraged to think differently about this issue? How did this particular player come to prominence?

These are good questions to ask of any process of institutional development. They should certainly inform your exploration of institutional development, both as history and as intervention. But they are by no means the only questions. I hope you are specifying your own. And I am about to add some more, related to other themes of institutional development which have been discernible in my exploration so far.

4.2 Key concepts of institutional development

Each of the passages that I have used to introduce the three ways of seeing institutions (as rules and norms, as shared meanings and values and as ‘big players’) also reveals other concepts needed to interrogate institutional development. In the next three sections we will look at these more closely.

Compliance and shared experience

Brett conceptualised institutions as sets of rules and norms. But if you look more closely at the following passage, you will see that he is saying other things about institutions:

Institutions are sets of ‘rules that structure social interactions in particular ways’, based on knowledge ‘shared by members of the relevant community or society’ (Knight, 1992, p. 2). Compliance to those rules is enforced through known incentives or sanctions … Institutions, by producing stable, shared and commonly understood patterns of behaviour are crucial to solving the problems of collective action amongst individuals.

I would highlight two concepts that emerge here:

- compliance: individuals and organisations are obliged to comply with the rules, through incentives and/or sanctions

- shared experience: institutions bring people and organisations together, ‘solving the problems of collective action’ (Brett, 2000, p. 18).

You can be disciplined, and ask the five Ws and H questions of each of these concepts. Take, for example, compliance:

- Who are the enforcers?

- What are the incentives/sanctions?

- Where do the incentives/sanctions come from?

- When does it become necessary to apply sanctions?

- Why are sanctions required?

- How are the sanctions enforced?

I am not going to devise a set of five Ws and H questions for all the concepts I am identifying here! I would encourage you, though, to do what I have just done, and devise your own questions for at least one of these concepts.

Individual agency and institutional contradiction

Engberg-Pedersen is as generous as Brett with his insights into the qualities of institutions and the nature of institutional development. Two aspects of his theoretical approach are of particular significance:

- Individual agency: Engberg-Pedersen places particular value on an individual’s critical engagement with elements of institutions that frame her or his behaviour. Quite apart from the general significance of this in institutional development, it has an important message with respect to professional behaviour and self-understanding. ‘Reflecting on the institutional context’ and choosing ‘action which confronts or bypasses a specific institutional element’ brings about change both socially and within the individual. The BancoSol story provides an example of one such action.

- Institutional contradictions: This is the title of Engberg-Pedersen’s article. He identifies something that will, if you are involved in any process of development, strike you as a critical issue in the process: the encounter between different and differing ‘symbolic orders’, most obviously the symbolic orders of, on the one hand, the ‘interveners’, and, on the other, the ‘beneficiaries’. This is an encounter in which the new symbolic order contradicts the old, with the interveners in effect saying to the beneficiaries, ‘You’ve got it wrong’. The beneficiaries, in return, think that the interveners must have got it wrong.

Relationships and power

What, finally, about the third view of institutions? Consider the opening two sentences of Hulme’s picture of the ‘institutional landscape for attacking global poverty’:

The institutional landscape for tackling global poverty is a vast terrain which lacks clear boundaries and involves a web of multilateral, national, sub-national and local institutions spread across the public sector, private business and civil society. It is also a dynamic landscape comprised of institutions reflecting the power structures and principles of different eras.

Two concepts are prominent here:

- Relationships: Hulme may be talking of the ‘big players’, but they are not players who play – or can play – on their own. Hulme uses a number of terms to spell out the reality that institutional development depends on relationships between agencies, its quality and qualities shaped by the dynamics of the relationships.

- Power: In my original look at Hulme’s picture, I suggested that, ‘Perhaps most strikingly, the picture is one of power plays and politics’. Power drives the action and that institutional development can be seen most fruitfully as the outcome of power struggles.

I might have selected many other concepts from each of the passages I have looked at. But I want to turn finally to a rather different kind of concept, that I can best illustrate with reference to the story of BancoSol: the concept of ‘levels of action’.

4.3 Levels of action

In the BancoSol story, you can see institutional development taking place at a number of levels. It is useful to distinguish between these levels, though it must be recognised that what is happening at one level is never in real life separate from what is happening at the others.

One conventional way of describing these different levels is to identify ‘macro’, ‘meso’ and ‘micro’ levels. I must immediately say that these terms can mean different things in different contexts. But I can suggest what might be a helpful way of understanding them by looking through the two lenses I identified for looking at institutional development: institutional development as history; and institutional development as intervention. Through these lenses:

Macro level:

- institutional development as history: broad structural change involving, for example, the way the international financial system works

- institutional development as intervention: activities that involve a broad range of ‘big players’ and are aimed at changing the wider social and economic structure; policy change at national and global level.

Meso level:

- institutional development as history: changing patterns of interaction between organisations and institutions

- institutional development as intervention: agencies involved in development action building relationships with each other in order to achieve common goals.

Micro level:

- institutional development as history: local change necessitated by broad structural change

- institutional development as intervention: change undertaken by local organisations that is designed to promote new norms governing their relationships.

Table 1 shows what this might look like in the BancoSol story:

| Level | Institutional development as history | Institutional development as intervention |

| Macro | BancoSol as part of broader structural change, as illustrated in quote from Rutherford | The creation of BancoSol contributes to the institutionalisation of micro-finance for commerce in Bolivia and more widely in Latin America |

| Meso | NGOs and other civil society agencies become more significant, stronger network emerges | BancoSol builds – or attempts to build – relationships with other agencies and organisations |

| Micro | Impact of recession and structural adjustment in towns: the unemployed and small traders seeking micro-capital | BancoSol deliberately builds its operations around the value of treating poor people with respect |

4.4 Identifying a conceptual framework

I have produced what is becoming a long list of concepts that are important in helping us to understand institutions and institutional development:

- rules and norms

- meanings and values

- big players

- compliance

- shared experience

- individual agency

- institutional contradictions

- relationships

- power

- levels of action: macro, meso, micro.

I want to draw this course’s studies to a close by suggesting you can treat this set of concepts – or, indeed, any other set you might have created – as a conceptual framework. By ‘conceptual framework’ I mean that these concepts can be connected with each other, enabling you to look at institutions and institutional development in a disciplined and powerful fashion.

I will illustrate what I mean by using these concepts to analyse a particular institutional landscape that I’ve needed to understand in my own work.

4.5 Analysing an institutional landscape

You may have noticed that I’ve used the term ‘institutional landscape’ at various points without explaining what I mean by the term. You may also have noted that it features in our learning outcomes. So what do I mean by it? And why is it important?

I am using the term simply to refer to the context in which a development action is to take place, but with attention focused on those aspects of the context (landscape) that might be considered institutional. So, in exploring an institutional landscape I would be looking, for example, for the ‘rules of the game’ that are being followed – the rules that I might want either to reinforce or to replace. By making use of the whole range of concepts in a conceptual framework I can create quite a complex picture, one that – all else being equal – I can use to inform the planning of the development action.

It is perhaps rarely – too rarely – that we undertake this kind of analysis in anything like a systematic fashion. But here, in Box 5, by way of an example, is an analysis of the institutional landscape that I might have constructed when in the first half of the 1990s I joined a team set up in Sheffield (a city in the north of England) to support civil society organisations increasingly expected to work in partnership with public sector agencies in the development and ‘delivery’ of social and healthcare services:

Box 5 An institutional landscape in Sheffield, UK

At first glance, the ‘big players’ were the most obvious features in the landscape. And, again at first glance, the big players were the public agencies: the health authority and the local authority social services department. That was where, it seemed, the power resided.

This needs to be qualified. The public agencies had the power of, amongst other things, funding and their statutory authority. But some civil society organisations had themselves become big players, particularly those which had both a local and a national identity. And civil society organisations were also empowered – to an extent – by central government’s desire to reduce the role of local government, changing rules and norms concerning service provision which had endured for years and making it less normal for social services to be provided by the local authority.

Shared meanings and values were also challenged in this institutional landscape. There were thus opportunities for civil society organisations to take up. But there were also threats. Relationships between civil society and statutory agencies were now intended to be embodied in contracts rather than grant agreements. This implied a more equal ‘partnership’, a different kind of relationship. But it also meant that civil society organisations might be tied into agendas other than their own, generating a potential threat to the values and integrity of those organisations, and the relative independence they had enjoyed.

Statutory agencies were themselves facing problems, not least the contradiction between the sense of themselves as the ‘authorities’ and the requirement (coming from central government) that they enter into partnerships with other organisations. ‘Sharing’ was for some officials a disconcerting prospect, and one to be resisted and avoided if at all possible: it didn’t make sense.

Within each sector, there were organisations or departments which were taking up radically different positions, often dependent on the influence of particularly ‘strong’ individuals who were determined to shape (or even set) agendas rather than be forced to work to others’ agendas. Macro- and meso-level influences were certainly at work, but there was room for manoeuvre at micro-level if individuals had the vision, creativity and influencing skills (or sheer bloody-mindedness in some cases) enabling them to exploit that room. There was also our new unit, a unit deliberately set up to bring together civil society organisations to help shape the rules of the new game, and to ‘help’ those organisations comply with the rules.

Our unit was funded by the statutory agencies, which gave rise to its own contradictions. ...

The case study in Box 5 is only a sketch, and one with which not all my colleagues would agree – a pointer to the fact that even with the discipline of a conceptual framework, judgements and analyses can differ. I hope though, that it gives you some sense both of what an analysis of the institutional landscape might look like and of the way in which a conceptual framework can be used.

4.6 Interrogating a conceptual framework

I want to suggest one other way in which a conceptual framework can be used.

Earlier, I suggested you might create a spray diagram which held together the different concepts I’ve presented you with relating to institutions and institutional development. I also suggested you might like to ask questions related to the concepts.

I now want to put those two suggestions together.

Activity 7 Using a diagram to interrogate the landscape

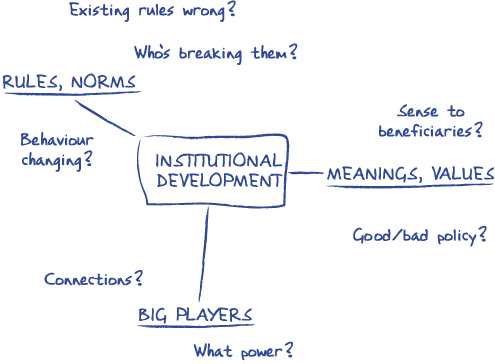

Create a spray diagram – or, better, spray diagrams – that are built around the concepts and annotated with questions. Here in Figure 1 is an example of what I mean.

This spray diagram links the three ways of seeing institutions: as rules and norms, as meanings and values, and as big players. It raises questions linked to each of them:

- Rules, norms: Who’s breaking them? Behaviour changing?

- Meanings, values: Sense to beneficiaries? Good/bad policy?

- Big players: Connections? What power?

Table 2 presents some ideas to think about coming from the diagram.

Figure 1 Spray diagram around a conceptual framework

| rules | What’s wrong with the existing rules? Who’s breaking them? And why? |

| norms | How has behaviour been changing? |

| meanings | What sense will this change make to those supposed to benefit from it? Why are people objecting to the situation? |

| values | What’s bad about this policy? In whose eyes? |

| big players | What power do they have? How do they relate to each other? |

My diagram is abstract, relating to no particular development action. I do think the questions are good, despite this. I suspect your diagram will be better if drawn with a specific situation or development action in mind.

Now draw your own diagrams.

Conclusion

In this free course, I have aimed to help you develop your understanding of institutions and institutional development by:

- identifying key concepts with which you can build up your understanding of institutions

- showing how these concepts can be formed into a conceptual framework that enables you to analyse institutional landscapes and institutional development

- suggesting that you can and should develop your own conceptual framework.

I have also presented you with a ‘story’ of institutional development. I trust this has shown that institutional development is a fundamental aspect of development and development management, in that (in this particular case) it is about creating new rules and norms and values through which people’s well-being can be enhanced.