An introduction to music research

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 27 April 2024, 2:35 AM

An introduction to music research

Introduction

In this free course we have gathered together materials to allow you to explore the ways in which music may be researched. After thinking about different kinds of musical knowledge and their relationship with various musical practices (including performance, composition, and listening), you’ll be introduced to some of the digital resources and methodologies that inform music research. The next section, which constitutes the main part of the course, explores a variety of different resource types that can be the focus for music research – including diaries, composer manuscripts, images, and instruments – before the final section introduces you to a contentious area of current scholarship: the relationship between music and politics.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University MA in Music (A873 and A874).

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand the ways in which musical knowledge may shape certain musical practices

identify the role digital methodologies play in music research

use, and make sense of, a number of online databases

understand the relevance of various different kinds of document for the study of music

understand something of the contentious relationship between music and politics, and its implications for the study of music.

1 Musical knowledge

Any type of research rests on a balance between what you already know and the potential it brings for developing new knowledge; and this section explores briefly a number of different ways in which musical knowledge shapes certain musical practices.

Activity 1

We've provided three musical extracts (Tracks 1–3). Listen to them first without being told what they are.

What sorts of information might help us to understand these pieces and their performance? Make notes before opening the discussion.

Discussion

An appreciation of all three examples would benefit from awareness of the contextual and cultural background to the music.

The first piece was Sibelius’s ‘Karelia’ Suite, a much-played orchestral work. Putting this piece into a research framework, your lines of enquiry could revolve around the national context against which it was composed and its relationship with the Finnish landscape (Karelia is a region of Finland as shown in the image below). Other topics might include its reception, its relationship with the composer’s biography, and the sources that led him to write this work.

If you are aware of the Anglican tradition, the second item may have sounded familiar as it is an adaptation of ‘When I Survey the Wondrous Cross’, sung by the Ntaria Ladies Choir in the Aranda (or Arrernte) language of central Australia. They live and perform in the village of Hermannsburg, close to Alice Springs.

The version presented here thus raises all sorts of questions:

- Who is singing it, and where?

- How might we write about the particular and unique vocal sound?

- What language are they using?

- How is the music harmonised?

- How does it sit within a religious context?

The third piece was a short march from Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, a 1670 opera by the French composer Jean-Baptiste Lully. Questions you might ask include:

- What were the circumstances of its composition?

- Where were such operas produced and what resources would have been required? What was their audience?

A piece like this also raises questions about the performing forces required.

- How do we determine the makeup of the orchestra in a situation where the score contains ambiguities?

- How should seventeenth-century notation be interpreted, and what do we know about the instruments of the period?

- What sources are available to enable us to probe these issues?

1.1 Knowledge and performance

You probably won’t be particularly surprised by the idea that musical knowledge might influence the way in which music is performed. As an introduction to the act of observing music in performance, section 1.1 focuses on an example of social music making. This way of thinking belongs in part to the broad field of music sociology, as articulated in an article in the Annual Review of Sociology:

Music is a mode of interaction that expresses and constitutes social relations (whether they are subcultures, organizations, classes, or nations) and that embodies cultural assumptions regarding these relations. This means that sociocultural context is essential to understanding what music can do and enable. Indeed, when the same music is situated across these contexts, it can work in dramatically different fashions (as sociologists would expect).

The communication seen in the following video clip operates on the ‘micro-social’ level (face-to-face interactions on a small scale). Here, though, it relates to the ways in which musicians work together as an ensemble, drawing on musical knowledge to create a piece of music. This piece is an example of a musical style called kwela, meaning ‘to climb up’, ‘to rise’, that has become traditional to South Africa and surrounding countries, although it emerged as recently as the 1950s. Originally kwela was an expression of dissent against an apartheid government, inspired by American big band jazz, while mixing this sound with traditional African musical styles and metal pennywhistles.

Activity 2

In video 1 a classical string quartet led by a South African musician, Samson Diamond, put together a piece of kwela. Watch the clip now and comment on the ways in which the players take up their roles.

Discussion

Samson teaches the simple melodic lines using traditional terminology, referring to key and time signatures. The cellist, Jeremias Sanz, appears remarkably relaxed and confident. He has never heard this tune before, but plays it straight back without error, reproducing it by ear. In contrast, the viola player, Carmen Craven-Grew, focuses on Samson’s fingers and learns it as much by looking as by listening. You can observe for yourself the last member of the group, Birgit Seifart, in the process of learning her line, and the group putting the parts together. Notice that they all slow down together at the end of the piece, by a combination of watching and listening. This clip shows you one method of passing on musical knowledge through interpersonal communication.

1.2 Knowledge and listening

Just as musical knowledge can inform or shape performance, it also changes the way in which we listen and understand music. One interesting kind of document to study in this regard is the concert programme note.

In his book Musical Meaning: Toward a Critical History, Lawrence Kramer notes astutely that, in the context of concert genres like the symphony, the explosion in written explications of music’s meaning in programme notes of the nineteenth century occurred at the very point where music was apparently proclaiming its autonomy from text (2002, p. 13). In other words, these programme notes may be interesting to historians of criticism for the way they engage with a range of critical concepts like ‘absolute’ music. Similarly, they may be useful for music historiography – the writing of music history. In particular, they may illuminate aspects of the reception history of a work or composer.

The collection of concert programme notes held in the New York Philharmonic Leon Levy Digital Archives is a fascinating resource (if still relatively limited at this time). It provides valuable documents for all kinds of reception history projects, since tracing how programme notes change over time can be a remarkably useful indicator of prevailing attitudes to composers and works.

Activity 3

Read the following programme notes from the New York Philharmonic’s archive:

- performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 7 in the 1948–49 season

- performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 7 in the 1961–62 season.

As you read, think about how the two sets of notes differ. How are they structured? What kinds of audience do you think they are written for, and what assumptions are made by the authors about the knowledge that audience possesses?

Discussion

There are many answers to these questions. Here are a few points of interest:

- The two music examples in the 1962 programme; these assume musical literacy, but nonetheless accompany quite approachable descriptions of the symphony’s movements.

- The need to apologise for using descriptive imagery in the 1948 programme. It appears to emphasise the classicising aspects of the symphony and its structure even as it admits that the question of whether Mahler’s symphony is ‘absolute’ music is open to debate.

- The use of quotations from a contemporary critic of Mahler’s time (Paul Stefan) in the 1948 programme note, and reference to the Mahler scholar Dika Newlin.

- The emphasis in the 1962 programme on Mahler’s biography is striking, especially in that it focuses on the composer’s health. Seeing Mahler’s symphonies in terms of the composer’s humanity is a critical tradition that Leon Botstein identifies in the post-1960 era (after the composer’s centenary celebrations triggered an increased interest in the man and his music – see Botstein, 2002).

1.3 Composition and knowledge

The teaching of composition in the eighteenth century, at least in Germany, was a matter of praeceptum, exemplum, et imitatio (learning the rules, studying examples and imitating the masters). In other words, it was considered largely a craft that could be taught rather than an intuitive skill shaped solely by an aesthetic vision. To some extent, of course, it still is; many contemporary composers study at universities and may become adept at a variety of compositional techniques, including functional harmony, species counterpoint or serialism. Yet, composers do not stop learning once their formal training is over. They may continue to study music in a variety of ways throughout their career.

Fred Karlin and Rayburn Wright, for instance, offer the following advice for contemporary film music composers: ‘You must know what the authentic sound is for each ethnic or historical project, but you can’t necessarily count on that sound to be perceived as authentic by the audience’ (2004, p. 86). Equally, they acknowledge that a strong period flavour is not always necessary when scoring film and television, especially if it is to communicate with a contemporary audience. Nonetheless, the film composer is expected to be stylistically flexible enough to produce ‘period flavour’ if asked.

Many television and other media productions now use production music, or library music. This is music held in large libraries to which composers may submit their compositions. Production companies then pay the library to license the use of the music. To some degree, this is nothing new (indeed, a number of film companies in the 1930s used stock music to cut back on their music production costs). The internet, however, allows anyone to search the contents of a library and to sample for free.

Activity 4

In this activity, you will look at a production library to see the variety of music that is available to production companies looking for stock music to accompany a period film or television programme. Some of this music is by recognised historical composers; much of it, however, is historical pastiche written by more recent composers.

Using SONOfind find something written by a living composer that is appropriate to accompany the opening titles of an Tudor- or Elizabethan-era historical drama series – perhaps a piece of music lasting 90 seconds or so. It needn’t necessarily be something that is historically accurate, of course – though you may choose something that uses period instruments. Searching by category and choosing existing keywords is a good way to start.

For some inspiration, you might search a website like YouTube for opening titles sequences to series such as Elizabeth R (BBC, 1971) or The Tudors (BBC, 2007). How easy is to find something appropriate? In what ways are pieces of music categorised, and do you find that categorisation useful? What is it in each piece of music that lends it its antiquated air, and how do some compositions negotiate between creating a sense of the past and the present (perhaps to appeal to a younger audience?)

2 Music and the digital humanities

The term ‘digital humanities’ means the use of computing for creating and processing data for research and dissemination in the humanities, an area which is growing and developing at incredible speed, transforming the field of music research. This section explores a number of digital projects centred on music, including the Open University’s own Listening Experience Database, and some of the new methodologies such resources demand.

An important point about these projects is that, while they use digital humanities tools for analysis and dissemination, their activities are not restricted to a virtual environment. On the contrary, they run seminars, conferences and performances.

Activity 5

Take some time to look at some of the major institutional projects that have used digital humanities techniques. Abstracts and links to them can be found on the Digging into Data Challenge, List of Data Repositories web page.

How many of these do you think might be useful for the areas of music research that interest you?

2.1 SALAMI and CHARM

Two projects that use the techniques of digital humanities to aid music research are SALAMI and CHARM.

The SALAMI project (Structural Analysis of Large Amounts of Music Information) is an inter-university project involving institutions in the UK, Canada and the USA. There is a helpful overview of SALAMI and what it is intended to achieve. The SALAMI project is feasible because of the existence of free datasets that include a body of music that can be the subject of analysis. An important resource in this respect is the Internet Archive (mentioned in the project description). This is one of several free sites. Another is Project Gutenberg, which includes a number of important books about music.

Musicians have used sound visualisation software to analyse musical performance as revealed in audio recordings. The value these programmes add to simply listening to music is that they can capture precise and scientifically accurate information about different performance parameters, such as tempo, phrasing and articulation. The Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music (CHARM) used such a programme in one of the strands of its project. It is also worth exploring this site and the site of the second phase of the project, The Centre for Musical Performance as Creative Practice (CMPCP).

2.2 Databases

All digital humanities projects use databases of some sort. These may vary in their content and the way they can be interrogated, but they are all based on the idea of assembling a large body of digitised data that can then be subjected to whatever processes its designers choose. These can be used for research, but also to provide answers for everyday musical questions. For example, the Aria Database is a practical tool used by singers and others working in the world of opera.

The allegro Catalogue of Ballads is part of the Broadside Ballads Project at the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Library, and aims to make original documents available to researchers through digitisation.

As the website explains:

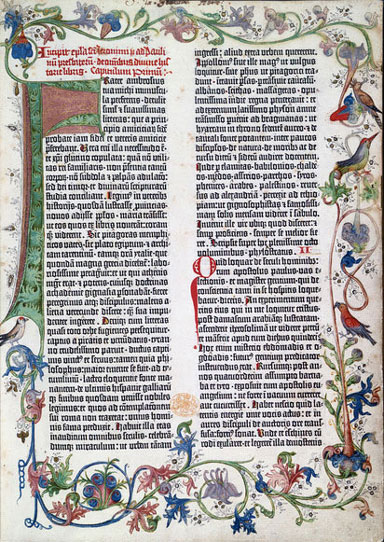

Broadside ballads were popular songs, sold for a penny or half-penny in the streets of towns and villages around Britain between the sixteenth and early twentieth centuries. These songs were performed in taverns, homes, or fairs – wherever a group of people gathered to discuss the day’s events or to tell tales of heroes and villains. As one of the cheapest forms of print available, the broadside ballads are also an important source material for the history of printing and literacy. Lavishly illustrated with woodcuts, they provide a visual treat for the reader and offer a source for the study of popular art in Britain.

(Bodleian Library, 2011)

2.3 Exploring ballads

The Bodleian library has a collection of over 30,000 ballads, and these have been gathered together into a single catalogue that, crucially, provides a digital image for each item. This allows researchers to compare multiple copies of the same ballad, or to consult the illustrations (which have themselves been catalogued using the ICONCLASS classification scheme). Sometimes a score is provided, and the catalogue provides an accompanying MIDI file. This is a very basic tool to give researchers who do not read music an indication of the tune to which these ballads were sung.

Activity 6

Spend some time using the browse and search facility of the allegro catalogue. For whom is this kind of catalogue intended? Note in particular the variety of indexes that can be browsed and the distinction made between browsing an index and searching. How useful or intuitive do you find the browse or search functionality? Make sure you look at some records to see the digital copies of the manuscripts.

Then try to use the search function to locate a song sung by Mrs Abingdon in a production of Twelfth Night.

Discussion

It seems pretty clear that this catalogue is intended primarily for researchers, and its interface is not all that easy to use. In particular, the search functionality requires specific practice to master, since it asks users to select appropriate indexes to search. How did you get on locating the song? If you simply searched for ‘Twelfth Night’ in the index devoted to ‘Titles, first lines, tunes’ or the index called ‘Title, first line, tune keywords’ you would not have found the song. If you searched for ‘Abingdon’ in ‘Authors, performers, venues’ you would not have found it either! It seems this performer is listed in the index as Frances Abington (1737–1815). The only way, it seems, to find this particular song in the search facility is to search for ‘twelfth’ AND ‘night’ as two separate search terms in ‘2 Title, first line, tune keywords’. You will also have had to use all lower-case letters to get any results at all (something that is only mentioned in the help guidance on using the database, accessible from the menu on the left of the screen). The last entry in the list it produces is the document you are looking for: ‘a new song, sung by Mrs Abingdon [Frances Abington], in Twelfth Night’ with the first line ‘How imperfect is expression’. When you look at the image, you will see that her name is spelled ‘Abingdon’.

Highlighting the difficulty of finding this one item should have given you some idea of the potential pitfalls that await you if you rely on searching databases without understanding how the search functionality operates. A casual look for ballads related to or sung as part of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, which might be the basis for an extended piece of research, may not have revealed this item.

The catalogue is undoubtedly a powerful tool, and in bringing together documents housed in different physical locations and making them accessible to external researchers, it has clearly made researching broadside ballads far easier. What is also clear is that it requires patience and time to use properly. Moreover, any user would benefit from a period of experimentation with the resource to understand better how it operates before relying on the outputs of an initial and hastily conceived search.

2.4 The Listening Experience Database

The Listening Experience Database (LED) is one of the most ambitious of the Open University’s digital humanities projects. The main purpose of the project is to design and develop a database, freely searchable by the public, which will bring together a mass of data about people’s experiences of listening to music of all kinds, in any historical period and any culture.

The project was conceived in the Music Department of the Open University and commenced at the start of 2013. It was inspired by an OU English Department project that had been launched in 2006, the Reading Experience Database (RED), which sought to capture a mass of evidence about the responses of individuals to reading. The RED project has been extremely successful; following its first phase, it branched out from its original UK remit to be taken up by international partners. It has become the major resource of its type in the world.

The big idea underpinning the equivalent music project was that there exists in the world a body of evidence that reveals the personal responses of individuals to the experience of listening to music. If a mass of such evidence could be captured it would provide a unique resource that many others could benefit from. For periods before about 1900, this evidence would be found in writings, both published and unpublished, in paper or electronic form. Material from later periods could also be drawn from other types of source, such as broadcast media.

3 Resources

Many different resource types play a role in the study of music, for example:

- Documents – different types of writings that inform musical scholarship

- Images – iconographical sources (visual images) and moving images that are associated with musical practices and that cast light on the performance and reception of music

- Places – environments and landscapes and their musical associations

- Repertories and musical sources – manuscript and printed sources, musical repertories and genres

- Instruments – issues concerning organology and performance practice

- Performances and recordings – the study of music as performed, and in particular the use of recorded sound as a source for music research.

In this section you will explore examples of all these resource types, before looking at ‘west gallery’ music to see how study of a particular topic may draw on a number of these.

3.1 Documents

One of the great joys of music research is looking at documents and unravelling the history to which they contribute. Through historical sources you can uncover new biographical information about a composer, patron, instrument maker or performer. Documentary research can contribute to the writing of the history of a musical institution, such as a music festival, concert society, opera company, publishing house, orchestra or town band. It can also shed light on musical performance. The sources you will encounter range in size and shape from huge multi-type archives such as those of the Metropolitan Opera –Metopera Database – and the Mozart: New Documents site to tiny, but possibly important, miscellanies. In recent years, one of the most extensive undertakings in this field is the large-scale Handel Documents Project, based at The Open University.

Newspapers can play an important part in the study of music. Apart from their concern with national and international affairs, broadsheets such as The Times, the Manchester Guardian and The Scotsman record for posterity the cultural life of a city or country, and there are many digital collections such as Welsh Newspapers Online. The reception of works and their performances can be gauged from contemporary newspaper reviews of premieres and subsequent performances.

3.2 Diaries

Diaries can also be very revealing. To take one important example, the daily thoughts of Samuel Pepys shed light on the performance and practice of music in seventeenth-century England – something that potentially might constitute important material for the Listening Experience Database. You can read his accounts in the excellent digital site, The Diary of Samuel Pepys, which in addition to its clear layout annotates the letters with explanations of the references within them.

Activity 7

An entry from the diaries of Frederick Kelly (1881–1916), an Australian composer killed during the First World War, is shown below. Why might this be considered an important source?

Wednesday 14 June 1911 Wentworth Hotel, Sydney

I went to the Sheffield Choir concert at the Town Hall after dinner. It was a miscellaneous program of choruses, part-songs and solos. The Sheffield chorus opened with Bach’s eight-part Motet, ‘Singet dem Herrn’, which they sang magnificently, kept the pitch tune as far as I could judge. They also did Elgar’s ‘Go Song of Mine’ which I heard at its first performance in London a year or so ago in the Queen’s Hall. It is a beautiful work, I think. Parry’s ‘There Rolls the Sleep’ and ‘The Bells of St Michael’s Tower’ (Knyvett-Steward) were also sung – the latter being a clever imitation of chimes. The Sydney Madrigal Society (conducted by W. Arundel Orchard) contributed ‘Thine Am I, Dearest’ (Monteverde) [sic] and Parry’s ‘Prithee Why’, and made an excellent showing – in fact I could find no fault with their singing. Lady Norah Noel’s singing left an unpleasant taste in my mouth. She sang a rather commonplace song as an encore and made the most of her gallery top notes. The bass Mr Robert Chignell was also up to the same game. It was interesting to have practically the only two characteristic sides of English music represented side by side – the part-song which is its pride and the drawing-room song which unfortunately is equally characteristic.

(Radic, 2004, p. 215)

Discussion

This detailed diary entry contains a wealth of information, here particularly concerning musical life in Sydney in 1911, which interestingly is dominated by British music. It also serves as a type of musical criticism, given Kelly’s judgements on the singers.

3.3 Images

Images of interest to musicologists encompass a wide variety of sources, and may include items as varied as abstract art, illustrations in a medieval manuscript, stage decorations, photographs of composers and their working environments, or the covers of records and compact discs (to name but a few).

Activity 8

Read a couple of the following ‘research stories’ by members of the music department, and compare the ways in which they use images in their work:

- Fiona Richards, ‘John Ireland and friends’

- Helen Coffey, ‘Painting instruments in the Renaissance’

- Helen Barlow, ‘Images of military bands’.

(Hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab.)

3.4 Composer portraits

One kind of image that may be of particular interest to the music researcher is the portrait. Portraits of composers can be found in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery (including photographic images as well as paintings or drawings). The images themselves can be fascinating, but you could also study the ways in which they have been catalogued. When does a ‘musician’ become a ‘composer’, for instance?

Activity 9

Use the ‘profession’ free-text search box on the Advanced Search page of the National Portrait Gallery’s website to look for various music professionals. You might start with ‘musician’ and see what comes up; then follow with ‘composer’, ‘violinist’ or ‘bandleader’.

Based on your knowledge of the people whose images are returned by the search, what might these terms suggest about the kinds of music associated with this terminology?

You ought also to compare the numbers of male and female sitters that are returned by the various searches.

- What does that suggest?

- Does it make a difference if you restrict your search to living subjects?

- Are there any female figures who have been painted or photographed more than others?

In addition, of course, you might look at the kinds of images that are returned by the search.

- What poses are adopted?

- How do the objects included in a portrait reflect the profession of the subject?

Clearly there are many questions that are presented by a simple archive of images, and you may well have thought of others.

3.5 Music for the moving image

Moving images also play a role in music study. The phrase ‘music for the moving image’ may cover a multitude of areas, including music for television programmes, music videos, websites, video games and film (which itself includes commercial narrative traditions such as those typified by Hollywood in an English-speaking context, documentary film or experimental art film). All these areas constitute a relatively new subdiscipline in mainstream musicology as it is practised in Anglo-American academic institutions.

Even so, critical attention has been focused on film music since its earliest days. Often this took the form of newspaper or journal criticism. Bruno David Ussher, for instance, had regular columns commenting on film music in the Los Angeles Daily News and Hollywood Spectator in the late 1930s and early 1940s, and the musicologist Frederick Sternfeld wrote a number of articles for journals such as the Musical Quarterly during the 1940s.

Further information

If you are interested in this, you can explore some American film music criticism of the 1940s by reading a publication entitled Film Music Notes (available on the Internet Archive), which was the official publication of the National Film Music Council. The articles often contained manuscript examples of scores reviewed.

3.6 Nature documentaries

You are now going to examine a couple of extracts from a BBC Nature Documentary, The Blue Planet, with music by George Fenton. One interesting aspect of the use of music in nature documentaries is the way in which it often ‘characterises’, even anthropomorphises, animals in ways that are familiar from feature film (or TV dramas). This might seem at odds with the stated aims of many documentaries: to present a scientific objectivity in relationship with its subject. Evidently that aim conflicts with the desire to entertain and to help audiences empathise with the documentary’s subject.

Activity 10

Watch two extracts from the ‘Open Oceans’ episode of The Blue Planet, with music by George Fenton (video 2). What effect does the music have on your view of the animals? In the case of the first extract (which presents us with a crab), what kind of characteristics are you encouraged to ascribe to this animal, and what role does music play in creating that character identity (alongside other elements such as the camerawork or the narration)? With the second extract (an attack on a shoal of sardines by striped marlin, juvenile tuna, and a sei whale), ask yourself where your sympathies lie. How does the music encourage us to side with one side or another? What does it suggest about the characteristics of the animals, and how does it accomplish this?

Discussion

Here are a few thoughts about the two sequences, though there is scope to say much more:

The crab in the first extract seems to be presented as something of a maverick. This is partly achieved through the cinematography (passages with close-ups and quick edits that create a confrontational and arresting character), but the music also plays an important role. Clearly, there are suggestions of music of the Far East – or, perhaps more accurately, musical signifiers that signal ‘the Far East’ to western popular culture. This is evident in the instrumentation (gongs, cymbals and a plucked Chinese zither-like instrument that sounds like the Guzheng) and the use of parallel harmonies. The music, then, appears to link this animal with a non-western cultural perspective; it is an outsider of sorts, and thus something of a maverick.

With the second extract, our sympathies probably lie with the sardines. Fenton’s music is written in the minor mode, which has an obvious effect on our reading of the scene, but there are some particularly interesting characterisations happening here. Aside from the allusions to Debussy’s La Mer, the marlin are given a graceful theme that seems to emphasise their beauty and power – but their music also features brass snarls, which are a standard connoter of evil or menace (and great power) in Hollywood film scores. The tuna, on the other hand, are given a sprightly repeating ostinato (with the odd militaristic snare drum), which might seem to indicate a certain ‘child-like’ obsessiveness of purpose (they are, after all, juveniles). When the whale appears, the musical movement slows down markedly. In fact, you might have observed how the music’s surface activity throughout the sequence parallels the size of the creature on screen: slower music seems to equate with more massive body weight. The whale’s appearance triggers a distinctly ‘tragic’ register in the music, as it appears to finish off the poor sardines who are seemingly obliterated. The music, in combination with Attenborough’s emotive narration, encourages us to sympathise with their fate.

3.7 Places

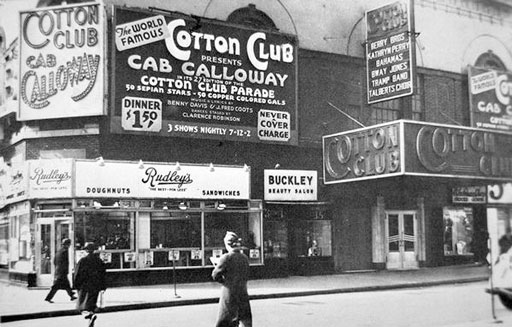

One growth area of musical research concentrates on the ways in which composition and performance are shaped by the environments and institutions with which they are, or have been, associated. Research around music and place might look at the ways in which landscape has shaped composition, or at the links between a building and its soundscape. Topics can embrace whole cities and their musics, or small performance spaces. They might range from the study of concert halls, such as the Leipzig Gewandhaus, to the conjunction of music and moving images in film scores where landscape is foregrounded, for example Philip Glass’s 1982 Koyaanisqatsi.

Often a venue might play a role in shaping performance and composition; New York’s Cotton Club, which opened in Harlem in 1920, became an influential performance space for jazz musicians, among them Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. Another important performance space is New York’s Carnegie Hall.

Activity 11

Carnegie Hall’s developing database contains records of events from its foundation in 1891. Open the Carnegie Hall Performance History Search page and search the conductor Walter Damrosch (1862–1950).

- What can you learn about him?

- Why was he important?

Discussion

Damrosch was an important figure in the history of music in America as director of the New York Symphony Orchestra, in which role he conducted the first performances of a number of works, including Gershwin’s An American in Paris in 1928. At the time of writing his name appears over 800 times in this database, his career closely linked to Carnegie Hall.

3.8 Musical sources

The study of notated musical texts takes place through:

- the sources themselves – manuscript and printed music

- musical editions based on the sources, which record the evidence on which the editor’s text is based

- literature concerning a work and its sources.

For many years, the study of manuscripts and early printed editions could take place only in a library, and this is still the case for much western art music. However, many musical sources have now been scanned and digitised, allowing their analysis at a distance. In 2013, the Britten manuscripts in the British Library were digitised as one of the projects marking the composer’s centenary. This is an extraordinarily rich resource, from which we can learn about his composing methods. Two other good examples are:

- the extensive collections in the Bavarian State Library, see MDZ Digitale Bibliothek Digital Collections: Musicsheets. music manuscripts

- the Jean-Baptiste Lully Collection in the University of North Texas.

Activity 12

Working with certain types of music can come with particular problems. Read Ben Winters, ‘Using film music sources’, which explains some of the issues.

3.9 Instruments

The study of instruments is often termed ‘organology’. This is an area of study that offers a range of possibilities in the use of digital resources – one of the reasons why it is important to digitise instrument collections is to make their images and sounds available to the widest possible audiences. It is, however, very much a developing subject, with many new projects expected in the next few years.

One of the first important collections to start to make its acquisitions available in a digital format was the National Music Museum (NMM) & Center for Study of the History of Musical Instruments. Based in South Dakota, it has extensive collections of western and non-western instruments, including the Cristofori piano and the Amati violin, as well as a huge array of collected non-western instruments, some quite extraordinary. See, for example, Images from the Beede Gallery: Serpentine Horn (Nagfani).

Activity 13

Spend a few minutes exploring the resources on the website of the National Music Museum (NMM).

Then open the page on Violin, The Harrison, which shows you one of the museum’s iconic Stradivarius violins. Focusing on this instrument, note some of the benefits of the NMM digital resources.

Discussion

- The instrument is available in high-resolution images, photographed on all four sides.

- It can be searched by area. Thus someone wanting to study violin scrolls, for example, can focus on this part of the instrument.

- There is a flexible search engine.

- There are sound files that demonstrate the range and quality of this violin.

- There is a bibliography directing you to further reading and other useful resources.

Activity 14

Choose an instrument and imagine you have to write an illustrated article on it. What information can you find on this site?

The NMM is not the only digital resource dealing with musical instruments. The Virtual Instrument Museum is a website showcasing the holdings of the World Musical Instrument Collection of the Wesleyan University Music Department in the USA. The site includes detailed descriptions and further reading on each instrument, and a wealth of photographs and video and audio recordings. There are also several collections in the UK that contain selections of instruments from around the world, for instance the Horniman Music Collection in London. Musical Instrument Museums Online (MIMO) is an extensive database which brings together instruments belonging to a consortium of museums and is essential browsing.

3.10 Performances and recordings

The study of performance involves looking at a number of resources, including recordings – although scores are sometimes a useful resource to look at, particularly for pre-20th-century performance. The evidence for significant variations in performance practice that result from major revisions of certain works can often be found notated in manuscript or published notated sources. The Online Chopin Variorum Edition, for instance, is a source-based study of published editions of Chopin’s music, and reveals much about the ways in which the composer’s music was performed.

With more recent performance, we may often have a recording to interrogate. Before studying recordings of western art music, though, it is important to consider what sort of documents they are: the history of their availability; how they have been made; how performers have approached them; what they are for; what their limitations are; the conditions in which musicians have performed and ways in which those conditions may have affected the manner of performance.

To take one simple example, there are not only differences between live and recorded performances, but also between live and studio recordings. These may sometimes be striking. We may recognise, for instance, that a live performance is likely to contain more ‘errors’ than an edited recording – where perfection can be gained through multiple takes, editorial sleight-of-hand and even correction of pitch. Some artists have even forsaken live performance in favour of the control available through the recording studio. The Canadian pianist Glenn Gould is a famous example of this, referring to the recording studio as a place where ‘the most horrendously constricting force of nature – the inexorable linearity of time – has been, to a remarkable extent, circumvented’ (Library and Archives Canada, 2004).

Further listening

You might like to listen to some of Gould’s recordings at the Glenn Gould Archive.

3.11 Tipperary

Often the first step when researching recordings is to locate them – and the resources of the internet may be particularly useful in this regard.

Activity 15

Find as many online historical recordings as you can of the 1912 song ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’ (also called ‘It’s a Long, Long Way to Tipperary’) by Jack Judge, which became particularly popular among Allied soldiers during the First World War. What search terms work best? Include home recordings in your search as well as those that were released commercially, and recordings that use the tune but change the words, or simply play the tune in an instrumental arrangement.

In what ways do the recordings differ? Do you recognise any other tunes that are interpolated in the arrangements? As part of your searching, you may find a parody song called ‘The Further it is from Tipperary’. How does that relate to the original song? You may also come across songs entitled ‘It’s a Long Way to Berlin, but We’ll Get There!’ and ‘It’s a Long, Long Way Back to the Good Old USA’. How do these compare? You may also come across an earlier unrelated song called ‘Tipperary’, which can be safely ignored!

Start with the following digital collections of early recordings, but make use of more general search engines such as Google, video-sharing sites such as YouTube or online encyclopaedias such as Wikipedia:

- Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project

- Belfer Cylinders Digital Collection

- Discography of American Historical Recordings

- Voices from the Dust Bowl.

How many separate, but relevant, recordings can you find? Don’t spend too much time on this activity (maximum 30 mins).

Discussion

Here are some initial items of interest, but you may have found many more.

Of the original song, these are six commercial recordings released around the time of the song’s composition (or slightly later):

Home recordings

- A home cylinder recording of the Church family singing a fragment of the song.

- Another home cylinder recording featuring the Church family singing another fragment of the song.

Closely related songs

- Billy Maury singing ‘The Further it is from Tipperary’, released in 1918.

- A 1940 home recording of Jim Holbert singing ‘The German Kaiser’ – a song using the same tune but with different words.

Evidently, the song has a much longer recording/social history than this. Looking at a site like YouTube also reveals much more about the broader cultural associations it has gained (in particular with a scene in Wolfgang Peterson’s 1981 film Das Boot, which was also released in an extended television version). A potential research project might take a song like this and trace both its recording history and its social and cultural significance, or subject changing performing styles to close scrutiny.

3.12 West gallery music

Studying a particular topic nearly always involves combining a number of different resource types. This is the case with the tradition of English rural church music known as west gallery music, from the eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century custom of placing the choir in a gallery at the west end of the church. Often the singers were accompanied by a village band, comprising a mixture of string and wind instruments, whose function was both sacred and secular. During the nineteenth century, many of these wooden galleries were removed, often being replaced by an organ.

This repertory and its performance traditions can only be reconstructed by drawing on a mixture of resources: books of music (manuscript and printed), images, documents and surviving instruments.

The west gallery choir and band are perhaps most familiar through many passages in Thomas Hardy’s novels, in particular Under the Greenwood Tree (1872). Hardy’s grandfather had played the cello in the Puddletown church band, and later in the Stinsford choir. Indeed, the bands for both villages were made up entirely from members of the Hardy family, playing a mixture of clarinets, piccolo, bassoon and viols.

Activity 16

The Mellstock Band have constructed and recorded repertory from Dorset. Listen to ‘Kiss Me My Love and Welcome – Drops of Brandy 1 and 2’. The bass instrument that enters towards the end of the piece is the ‘serpent’, a frequent member of the west gallery band.

4 Music and politics

In this last section, you will study some of the ways in which music and politics are linked, ranging from the reception of Wagner and Beethoven in Nazi Germany, and music’s role in the Cold War, to the protest song.

There are numerous ways in which contemporary musical practice appears to be deeply embedded in the politically-charged world around us. You may be familiar with the Eurovision Song Contest, for example, which in its voting patterns frequently appears to be less about the songs and more about international relationships between the voting countries. And you may also be able to think of other ways in which popular musics of different eras have been associated with particular political positions.

Popular musicians are courted by political parties keen to have their messages endorsed, or their images improved. Well-known examples of this include Frank Sinatra’s role at John F Kennedy’s presidential inauguration and Sheryl Crow’s endorsement of Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign (she also performed at the 2008 Democratic National Convention). Indeed, US presidential elections often make prominent use of dedicated campaign songs, drawing in recent years from existing popular culture – though this is far from a new phenomenon, and earlier elections could be just as sophisticated in their use of music (see Harpine, 2004 on the functions of songs in the 1896 presidential campaign of William McKinley, which frequently expressed a belligerency in their attacks on opponents that was absent from the candidate’s speeches).

4.1 Western art music and politics

In addition to popular music, Western art music is also deeply implicated in the complex world of politics no matter how often people attempt to deny it.

Activity 17

Watch these two videos, which explore different aspects of music’s relationship with politics. How would you characterise the attitudes on display?

Discussion

The audience at the BBC Proms concert seem to be rather annoyed that an overtly political act has disturbed their enjoyment of the music – though, to be fair, it seems as though the protestors are not objecting to the music played, but rather the symbolism of the orchestra’s nationality. This might make you wonder how easy it is to disentangle ‘the music’ from the identity of those performing it.

As explained in the second video, the concert of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, given in Berlin just after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, makes changes to Schiller’s text in the symphony’s finale. Here a political event has prompted a musical celebration and a change to the usual words performed. It is difficult not to see this as deeply political, though one suspects many of those involved with the performance would claim this was an apolitical act that rose above politics.

Both videos, then, might seem to grapple with the ways in which music is held by some to transcend the everyday world of politics (understood broadly, rather than in its narrow party-political or ideological sense) while at the same time demonstrating how easy it is for music to be used to make a political point, or to be the focus of a political discourse.

In order to admit this kind of response to music as relevant to the study of music history, though, musicologists needed to change their attitude to a fundamental question: what is the object of study? In other words: what, exactly, constitutes music in a disciplinary sense? Where does the subject begin and end? Should studying music be restricted to the notes themselves, or might it include studying the societies and cultures in which it is practised?

4.2 Wagner and the Nazis

One composer who might be thought of as deeply implicated in politics is Richard Wagner (1813-1883). Indeed, many of you might have named Wagner if asked to think of a composer of Western art music whose music, writings, and reputation are somehow bound up with politics. His popular image is forever tarnished by his antisemitic writings and his attractiveness to Adolf Hitler and German nationalists as a cultural icon – such that many Israeli musicians refuse to perform his music. Yet, at the same time, his music is deeply admired by many who would simultaneously disavow his beliefs and the uses to which his music has been put.

Activity 18

The literature on Wagner is enormous, but to get a sense of the controversy that still surrounds Wagner’s music, read this short article by Lili Eylon on the pages of the Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs (the ‘official’ nature of the website is perhaps an indication that consideration of the question is one that carries contemporary political relevance).

4.3 Beethoven and the Nazis

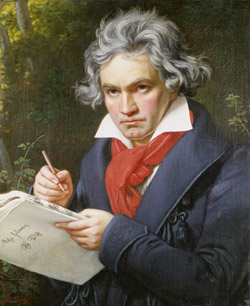

You’ve already heard a little about Beethoven’s prominent position in the celebratory events surrounding the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. This is just one of a number of instances in which Beethoven has been connected with political events or ideologies, stretching back to his reported desire to dedicate the Third Symphony to the liberating Napoleon Bonaparte and his subsequent scratching out of the dedication once he learned that Napoleon had declared himself Emperor of France.

Indeed, as David B. Dennis notes, “German political leaders have consistently associated Beethoven with ideologies they promote and actions they undertake” (1996, p. 3); however, it is also the case that it tends to be Beethoven the man that is their focus, particularly in the struggle to overcome his deafness. The political views of the composer himself, however, seem to have been remarkably ambiguous, with his attitudes towards the enormous political and social upheaval of his times unclear at best, and often seeming to swing alarmingly from one position to another (1996, pp. 23-24).

Much of Beethoven’s music was interpreted by Nazi critics as serving a German national myth marked by a certain belligerency. Arnold Schering suggested that the Fifth Symphony, for example, represented a “fight for existence waged by a Volk that looks for its Führer and finally finds it” (Dennis, 1996, p. 151) and the Seventh Symphony was described as a “victory symphony” when the Berlin Philharmonic performed on tour for German soldiers in 1940 (ibid., p. 168). Soldiers were also encouraged to listen to Beethoven’s symphonies in regular radio broadcasts to provide them with the stamina to fight better (ibid., p. 166) and even children’s books suggested that Beethoven’s symphonies were nationalistic fight-songs (ibid., p. 153).

4.4 Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony was subject to some particularly interesting interpretations in Nazi Germany. Its closing choral section was performed at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, and it was heard in its entirety in a performance by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler for Hitler’s birthday in 1937. This was at the specific request of Joseph Goebbels and, as the newspaper Der Angriff noted, the symphony was regarded as a perfect choice because “with its fighting and struggling” the work denoted the Führer’s capacity for “triumph and joyous victory” (Dennis, 1996, p. 162).

In the Nazi propaganda film Schlußakkord (dir. Douglas Sirk, 1936), a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony broadcast on the radio reaches the ears of an ill German woman living in the United States. By the time the finale has finished, she has miraculously revived and has resolved to return to Germany to take up her duties as a mother (Winters 2014, p. 99). The music, it seems, has inspired her to re-join a group from which she has been separated – which is precisely how the Nazis hoped music would operate, drawing together Aryan Germans and separating them out antagonistically from the other races, with whom they had long lived peaceably.

What did the Nazis hear in Beethoven’s Ninth? Evidently, the triumphant and celebratory tone of its final movement, and the immense struggle apparent in the first movement easily map on to an idea of German victory after a period of conflict; however, that is equally true of many nineteenth-century symphonies. The Ninth also has a text, though, that makes it particularly susceptible to appropriation. Below, I’ve reproduced some of Schiller’s text from the choral section of the symphony. At first glance, there is little in this that might seem to support the ideological premise of Nazism.

…Seid umschlungen, Millionen! Deisen Kuß der ganzen Welt! Brüder, über’m Sternenzelt Muss ein lieber Vater wohnen. Ihr stürzt nieder, Millionen? Ahnest du den Schöpfer, Welt? Such’ ihn über’m Sternenzelt! Űber Sternen muss er wohnen…. |

…Be embraced, millions! This kiss for the whole world! Brothers, above the starry canopy Must a loving Father dwell. Do you bow down, millions? Do you sense the Creator, world? Seek Him beyond the starry canopy! Beyond the stars must He dwell… |

Hans Joachim Moser, though, who was part of the Reich-Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, noted of Schiller’s text that the “kiss for the whole world” was a “glowing devotion to the notion, the dream, the simple idea of a humanity conceived in as German terms as possible” (Dennis, 1996, p. 152).

4.5 The Cold War

Music’s close association with politics did not end with the defeat of the Nazis (no matter how much the high modernists of the 1950s hoped it would). In the early years of America’s Cold War with the Soviet Union, institutions like the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the House Un-American Activities Commission (HUAC) or Senator Joseph McCarthy’s committee within the US Senate investigated persons suspected of being communist agents and purveyors of communist propaganda. They were particularly interested in artists active in Hollywood, and even with musicians.

The composer Aaron Copland was called to testify to a closed hearing of Senator McCarthy’s Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in 1953 because of his involvement in a foreign exchange programme, and his state-sponsored foreign travel to Latin America and Italy. He had already been placed on a State Department blacklist banning his music from the American libraries in some 90 countries controlled by the United States Information Agency (Crist 2008, p. 491).

If you wish, you can read a transcript of Copland’s testimony here |

Similarly, the American folk musician Pete Seeger was summoned before a sub-committee of HUAC in 1955. You can read a transcript of his interview here.

Seeger was happy to answer questions about the songs he sang, but was not prepared to divulge where or with whom he sung them. It’s fascinating to read of the attempts of his interrogators to bait him in order to divulge his political beliefs. Equally, it is striking to see how Seeger attempts to divest the songs themselves from the political situations in which they may have been used.

4.6 Hanns Eisler

German composer Hanns Eisler (1898-1962) was also investigated extensively by the American authorities because of his impact as a composer of political songs in the 1920s, a sense of which might be gauged from the following comment by Michael Haas:

Hanns Eisler’s use of music as a ‘political weapon’ would be a defining element in Weimar Germany. Many from the political centre and right would claim that Eisler’s music was a factor in this shaky German Republic becoming unstable, even ungovernable.

That’s quite a claim. Yet, Eisler’s collaborations with the agitprop performer Ernst Busch in the late 1920s, and the writers surrounding Bertolt Brecht (including Brecht himself) certainly produced cultural products of undoubted political significance that reflect the composer’s deeply-held Marxist beliefs.

Eisler was eventually forced to leave the United States and ended up in the newly-formed German Democratic Republic (the Eastern part of Germany controlled by Communist authorities sympathetic to the Soviet Union). Such was the power of Cold War division of lines that David Blake noted in a 1980 Grove article that “No composer has suffered more from the post-1945 cultural cold war. As the cross-currents between Eastern Europe and the west increase, a proper international assessment of his achievement must be made.” (quoted in Wierzbicki 2008).

If you like, you can read Eisler’s statements before HUAC here |

Activity 19

Look briefly at the FBI’s files on Eisler

What problems do they present for the casual researcher? How easy is it to navigate the file or find relevant information?

For some scholarly reflection on Eisler’s FBI file, you might like to read an article by James Wierzbicki (2008) in Music and Politics. |

4.7 The protest song

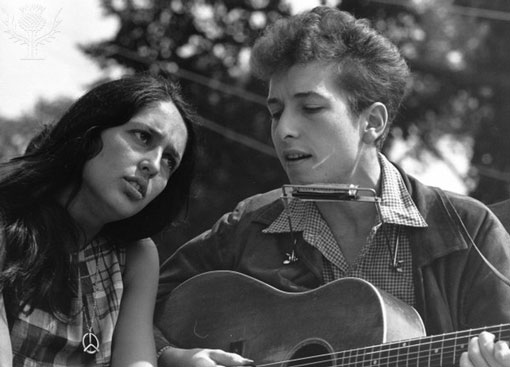

1960s America is one of the first places many of us would associate with the protest song – and, if asked to name prominent individuals involved in the writing and performing of such songs, we might point to the singer-songwriters Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. Undoubtedly, the country was a hotbed of political tension, stoked by the war in Vietnam and the pressures of Cold War rivalry with the Soviet Union, while the immense social changes at home brought about by the civil rights movement ensured that race was high on the cultural agenda. Many of these themes are explored in songs that were brought to national attention as part of the enormously successful folk-music revival – a complex mixture of political activism, folk music, and commercialism, in which competing priorities are not always easy to separate.

Activity 20

Watch this film of Joan Baez performing three songs at the BBC in the 1960s. What aspects of her performance strike you as significant?

Discussion

Perhaps the most significant characteristic of her first song “Troubled, and I don’t why” is the strong sense of community she seems to create amongst her audience – fostered through the act of singing together (with the audience joining in the words of the chorus). The words of this first song are topical in their apparent criticism of mainstream media (newspapers, television, movies) and without being specific to any events communicate a sense of group unease. Similarly, she asks her audience to join her in singing “We Shall Overcome”, though no tuition is necessary, such is the simplicity and familiarity of the tune and the words. Baez signals only changes to the initial words of the verses, allowing her to shape the mood of her audience. Her final song is Bob Dylan’s “With God on Our Side” which allows her to more easily showcase her obvious vocal abilities, and distinctive vibrato, though its words are perhaps less audible as a consequence: it also requires a spoken introduction while Baez picks out chords on her guitar, suggesting its message is somewhat more complex and nuanced. There is much more that could be said about these performances, including aspects of her appearance, the set design, and the ways in which she is filmed. Undoubtedly the purity of her voice and her physical beauty also play a key role in the aesthetic experience.

4.8 Ton Steine Scherben

The protest song also played a prominent cultural role in the politics of West Germany in the late 1960s and early 1970s. As Timothy Brown states: “radical music and radical politics were mutually constitutive [in West Germany]. Not only did rock music both generate and mirror the ideas and slogans of the movement…but it mirrored, in its modes of cultural production, larger themes of the protest movements that rocked West German society in the sixties and seventies” (2009, p. 2).

As Brown’s research reveals, a significant group in this regard were Ton Steine Scherben (usually translated as Clay, Stone, Shards – a nod in part to The Rolling Stones). They had their origins in the radical street theatre of the 1960s, and in an earlier incarnation had written a Singspiel depicting the conflicts of everyday life. It featured a song that became the group’s first single, “Macht kaputt was euch kaputt macht” (Destroy that which destroys you) which speaks of the frustration of a man caught in a world of impersonal forces (Brown 2009, p. 8). It also expresses a deeply political scepticism of contemporary consumer culture, and in that sense connects with the radical politics of the left – which in West Germany at this time were even manifested in terrorist activities by groups such as the Red Army Faction (often known at the time as ‘The Baader-Meinhof Gang’).

Activity 21

Listen to this extract from “Macht kaputt was euch kaputt macht” to get a sense of the musical style.

If you’d like to read the German lyrics for “Macht kaputt was euch kaputt macht,” you can do so here. |

4.9 The sound of protest

The raw sound of Ton Steine Scherben’s “Macht kaputt” is striking: it’s certainly very different from the ballad-like performances of Dylan or Baez in the United States. Significantly, the group were the first German rock band to sing in their native language (Brown, 2009, p. 8). Their songs were written in a rough vernacular German, the better to communicate with their intended audience – the working class of the Kreuzberg area of West Berlin, where the band also lived. At the time, Kreuzberg was a run-down area bordered on three sides by the Berlin Wall, and was particularly popular with students due to its cheap rents.

Evidently, the protest song is also a genre with a wide appeal – and this course has aimed to suggest the possibility of looking beyond Anglo-American culture for pertinent examples. What’s significant is the variety of musical styles evident and the difficulty in pinning down precisely where the element of protest lies. Most would probably point to the lyrics, but undoubtedly the style of the music (and the way that style is interpreted in the context of prevailing music-making) plays an important part in a song’s status as a ‘protest song’, as do the identities of the performers, and the contexts in which the music is heard.

Conclusion

This free course has introduced you to different kinds of musical knowledge and their relationship with various musical practices (performance, listening, and composition); and to some of the methods and resources for studying music, within the context of the digital humanities.

It has also introduced you, though, to an area of music study (music and politics) that raises some interesting issues about what exactly we mean by studying ‘music’. Looking at the way in which music and politics can be connected calls into question the assumptions we may have about the identity of music - about the boundaries and edges of what constitutes ‘the music itself’. From the activities of performers, listeners, composers, and musicologists, it seems that it is frequently difficult to divorce discussion of ‘the music’ from its worldly contexts. Although (some) music analysts or music aestheticians may still maintain that there is such a thing as ‘the music itself’ or argue that music has no meaning beyond its aesthetic meaning as music, there can be little doubt that to ignore these interactions between music and politics is to close the door on rich and fascinating areas of study.

Appendix 1 John Ireland and friends

Fiona Richards

Knowledge of the life and music of John Ireland (1879–1962), like any biographical work, can be greatly enhanced by images that reveal places and people that were important to the composer. Our understanding of the time when he was producing his most personal music, roughly speaking 1918–30, is hampered by the fact that so few biographical sources have survived. There are many reasons for this, among them the destruction of Ireland’s property both during the Second World War and after his death. It was therefore very exciting for me to discover two hitherto unused and unknown resources relating to people who played a significant part in Ireland’s life and works. Both of these were young people, one a boy from Chelsea (Arthur Miller), the other a young woman pianist (Helen Perkin). Until 2000 there were no pictures in print of either of these figures, yet Ireland dedicated his Piano Concerto to Perkin, who premiered the work at the Proms in 1930, and wrote several piano, vocal and chamber pieces for Miller. Until only recently they remained enigmatic, known only through reviews and through Ireland’s music itself.

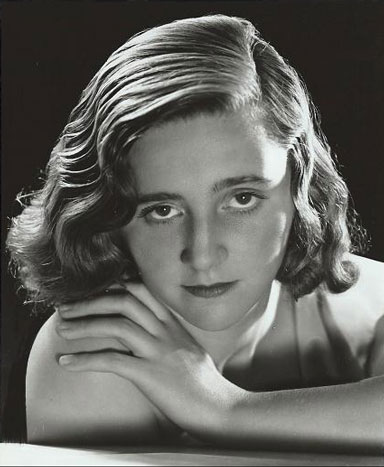

The first source was in the care of Perkin’s youngest son in Sydney, and consisted of a number of photographs, as well as many programmes, reviews and suchlike. Seeing Helen Perkin (Figure 1) perhaps helps to reveal why it was that Ireland should choose such an inexperienced performer to play the solo role in one of his biggest works.

The second source was if anything even more fascinating. Owned by the John Ireland Trust, a little bundle of undeveloped negatives was accompanied by a list detailing their contents, even dating them very precisely. These included several photographs of Arthur Miller (see Figure 2), but also supplied invaluable missing biographical material, even down to the fact that we now know exactly where Ireland was on 22 August 1922!

Appendix 2 Painting instruments in the Renaissance

Helen Coffey

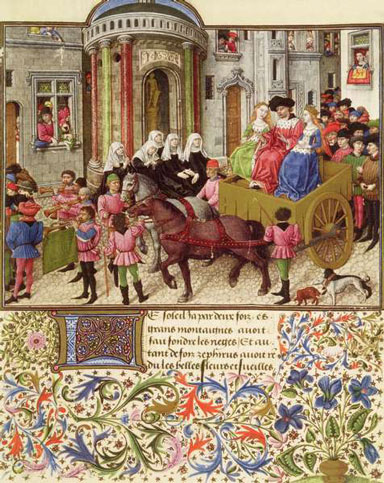

Archival records provide details of the wind bands which were employed in many cities and courts in western Europe from the mid-fourteenth century. Payment lists confirm that these ensembles typically numbered between two and five members, and generally consisted of two or three reed instruments (shawm, bombard) together with a brass instrument. Although payment lists provide valuable information about these ensembles, scholars have turned to iconography (such as the image presented here), to gain further insights into the performances and instruments of these musicians.

This picture of c.1470, believed to be by the Flemish painter Barthélemy d’Eyck, is one of sixteen miniatures that illustrate a French translation of Boccaccio’s epic poem of the legend of the Ancient Greek hero Theseus. This particular miniature depicts Theseus’s triumphal procession through Athens. Despite the subject of the miniature, the artist obviously drew on his everyday experiences in his work: we therefore see the reed and brass instruments of the civic and court wind bands at that time, as well as the ensembles’ customary practice of performing without reference to written music.

Scholars have used images such as this to determine the form of the brass instrument used in these ensembles, as archival references can be ambiguous in their descriptions. Many fifteenth-century images show trumpeters playing on s-shaped or folded trumpets (as here) in which the players appear to be moving a slide, placed after the mouthpiece. The instrumentalist’s left hand seems to hold the mouthpiece near the lips while the right hand supports the main body of the instrument, pulling and pushing the instrument towards him and thus enabling performances in more than one harmonic series. The evidence for the development of the slide trumpet (the precursor to the trombone) during the early fifteenth century is mainly based on images such as this – there is little mention of this instrument in archival records before the end of the century. Scholars such as Keith Polk (1989) have used these pictures to demonstrate the instrument’s popularity during this period, even after the trombone gained prominence in later years.

Reference

Appendix 3 Images of military bands

Helen Barlow

Having trained originally as an art historian, my instinct is to ask not only ‘what does the image show?’, but also ‘why and how was it made?’

Figure 1 shows a drawing from the sketchbook of a minor artist, George Scharf (1788–1860). An artist uses a sketchbook for preparatory work – often on the spot as an aide memoire for future paintings. For that reason, a sketch may be far from ‘sketchy’ – it may be a detailed record. Here, Scharf has taken pains with the uniforms and instruments, and the location and occasion are clearly identified in his own hand – ‘Marine Officers Mess Room at Woolwich, during Dinner’. The details tell us something about the transitional nature of the instrumentation of the military band in the 1820s, with trombones coexisting alongside serpents, which they would soon replace.

The image also gives us clues to several other avenues. What about the boys who are holding the music? Military music education was only centralised and formalised in 1857, so perhaps this image gives us an insight into the role of boys in bands and how they received musical training before then. From the instrumentation and from the occasion, dinner, we might deduce that sophisticated instrumental repertoire was being played. And this image also strongly indicates the gentlemanly, socially exclusive culture of the officers’ mess of that period, and identifies one of the distinctly unwarlike performance contexts in which regimental bands played.

Appendix 4 Using film music sources

Ben Winters

In my work as a film music scholar I often face a number of challenges when engaging with a film’s score, not all of which may be apparent to the casual reader when faced with the published outcomes of my research. I want to highlight some of these using examples of my own publications. Usually, music written especially for a film tends not to be published (see Winters, 2007a for a discussion of these issues) and as a result if I want to engage with and discuss the musical content of such a score in an academic publication, I am faced with three options, all of which I have used at some point:

- Option 1. Consult manuscript sources held in archives, and publish extracts from these sources as musical examples in a publication. I did this with my work on Erich Korngold’s score for The Adventures of Robin Hood (Winters, 2007b), but had to gain permission from Warner Bros. to do so (both to access the archive, and to reproduce manuscript sources photographically or re-set music examples in music notation software).

- Option 2. Often, however, it’s not possible or practicable to get hold of such manuscript sources (for many different reasons, including the access policy of copyright holders, and the costs involved in this kind of research). In such cases, I might rely largely on my own written descriptions of the music’s content, augmented with aural transcriptions from the film (see Winters, 2012a, in which I transcribe motifs from John Williams’s score to the 1978 film, Superman: The Movie). I often choose this option when presenting papers at conferences if I particularly want to discuss musical content in a modest amount of depth. In the case of the Superman score, Equinox Press was happy to publish these short motifs without seeking permission from the copyright holder, citing fair dealing under copyright law.

- Option 3. For various copyright or cost reasons, or the timidity of publishers, often it’s simply impossible to include any musical extracts from the score under consideration. As a researcher, I’ve sometimes been forced to present research without any musical examples at all (e.g. Winters, 2014a). Often, of course, such an approach is entirely suitable for the publication’s argument, which may focus on music’s interaction with narrative strategies, rather than any in-depth exploration of the ‘nuts-and-bolts’ of the way the music is constructed.

There are other instances, though, in which the music used in a film may be published already. Sometimes, existing scholarship will present extracts that can be quoted in a new context. This was certainly the case when I engaged closely with Hugo Friedhofer’s score to The Best Years of Our Lives (see Winters, 2012b). I drew on published extracts from this score in Burt, 1994 so that the reader could gain some sense of the style of the score and the music to which it alludes. Alternatively, films may draw on existing published works in the western art music tradition, in which case it becomes relatively easy to quote them as examples, perhaps with added information about the content of the image or dialogue at various points. I adopted this strategy when discussing a scene in Double Indemnity (dir. Billy Wilder, 1944) in which Schubert’s Symphony No. 8 is playing in the background, with the scene functioning almost as an example of nineteenth-century melodrama (see Winters, 2014b, pp. 165–70). I reduced the Schubert extract to piano-score format, and annotated it to give readers a sense of the way in which the musical gestures operated alongside the dialogue heard in the scene:

Extract from Schubert, Symphony No. 8 (reduced to piano-score format), as used in Double Indemnity

In all these cases, the decisions I make about my research questions, methodology, and dissemination of my research may be affected fundamentally by the availability of the sources and the likelihood of copyright problems.

References

Burt, G. (1994) The Art of Film Music: Special Emphasis on Hugo Friedhofer, Alex North, David Raksin, Leonard Rosenman, Boston, Northeastern University Press.

Winters, B. (2007a) ‘Catching dreams: editing film scores for publication’, Journal of the Royal Musical Association, vol. 132, no. 1, pp. 115–40 [Online]. Available at http://www.jstor.org.libezproxy.open.ac.uk/stable/30152960 (Accessed 28 February 2014).

Winters, B. (2007b) Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s The Adventures of Robin Hood: A Film Score Guide, Lanham, MD, Scarecrow Press.

Winters, B. (2012a) ‘Superman as mythic narrative: music, Romanticism, and the “oneiric climate”’, in Halfyard, J.K. (ed.) Magic, Myth and Monsters: Music, Sound and Fantasy Cinema, Sheffield, Equinox Press, pp. 111–31.

Winters, B. (2012b) ‘Musical wallpaper? Towards an appreciation of non-narrating music in film’, Music Sound and the Moving Image, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 39–54 [Online]. Available at Art Full Text (H.W. Wilson), EBSCOhost (Accessed 28 February 2014).

Winters, B. (2014a) ‘Swearing an oath: Korngold, film and the sound of resistance?’ in Levi, E. (ed.) The Impact of Nazism on Twentieth-Century Music, Vienna, Böhlau Verlag, pp. 61–76.

Winters, B. (2014b) Music, Performance, and the Realities of Film: Shared Concert Experiences in Screen Fiction, New York, Routledge.

References

Further reading

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Ben Winters, Fiona Richards, and Trevor Herbert.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this unit:

Course image

Figure 1: Bridgeman Education

Figure 2: Fiona Richards

Figure 3: Bridgeman Education

Figure 4: Bridgeman Education

Figure 5: Bridgeman Education

Figure 6: Bridgeman Education

Figure 7: Bridgeman Education

Figure 8: Bridgeman Education

Figure 9: Bridgeman Education

Figure 10: Bridgeman Education

Figure 11: Bridgeman Education

Figure 12: Bridgeman Education

Figure 13: Bridgeman Education

Figure 14: Bridgeman Education

Figure 15: Bridgeman Education

Figure 16: Bridgeman Education

Figure 17: Bridgeman Education

Figure 18: Britannia

Appendix 1: Figure 2: Photo courtesy of the John Ireland Charitable Trust.

Appendix 2: Figure 1: Bridgeman Education

Appendix 3: Figure 1: courtesy of The Trustees of The British Museum

Appendix 4: Figure 1: Bridgeman Education

Audio 1: extract Sibelius ‘Karelia’ Suite 1st movement Sibelius Essentials track 2 (Warner 2008)

Audio 2: extract from ‘Tha Ntulka Tjuraarama-nga (When I Survey the Wondrous Cross) Ntaria Ladies Choir (1999)

Audio 3: extract from Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme 1670 opera by French composer Jean-Baptiste Lully track 4 from Le Concert des Nations/Jordi Savall Alia Vox 1999

Audio 4: Kiss me my love and Welcome Drops of Brandy 1 and 2, Mellstock Band courtesy www.saydisc.com

Audio 5: extract from Macht kaputt was euch kapputt macht David Volksmund Produktion (1991)

Video 1: The Diamond Quartet plays example of South African Kwela music ‘Asikatali’ traditional Zulu song, specially recorded by The Open University

Video 2: Extract Open Ocean’s episode of The Blue Planet © BBC

Video 3: © BBC News (2011)

Video 4: extract from BBC broadcast 25. 12. 1989 spoken introduction to Berlin Freedom Concert

Video 5: Joan Baez BBC Broadcast in the 60’s

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don’t miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.

Copyright © 2015 The Open University