Hadrian's Rome

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 22 January 2026, 10:21 PM

Hadrian's Rome

Introduction

This free course, Hadrian’s Rome, explores the city of Rome during the reign of the emperor Hadrian (117–138 CE). What impact did the emperor have upon the appearance of the city? What types of structures were built and why? And how did the choices that Hadrian made relate to those of his predecessors, and also of his successors?

Hadrian provides an interesting case study. He was a well-travelled emperor, who spent much of his reign away from Rome, surveying the empire. This might suggest that, to Hadrian, Rome was not of central importance. However, he was a prolific builder and funded extensive building schemes in Rome. He grasped the symbolic importance of the city as the hub of the empire, a place where the emperor needed to make his presence felt, even in his absence. Furthermore, Rome under Hadrian saw some architectural innovations and was a place that was embellished and influenced by the riches of empire. Hadrian’s reign underlined that Rome and empire were integrated rather than separated.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course A340 The Roman empire.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

demonstrate a critical understanding of a range of types of evidence for Hadrianic Rome, including literary sources, inscriptions, coins and buildings

describe the impact Hadrian had upon the appearance of the city of Rome

compare and contrast different interpretations of the Pantheon and other Hadrianic monuments

discuss how the wider Roman empire was visible in the art and architecture of Hadrianic Rome

evaluate the significance of commemoration after death to emperors, and how this was linked to divine rights to rule.

1 Introducing Hadrian

The aim of this section is to find out a little more about Hadrian and the major sources of evidence for his reign.

This is a colour photograph looking up from the right at the head and shoulders of a man shown against a flaxen background. The man is turned towards the viewer’s right. He is shown with curly hair and a close-cut beard and moustache. He has a Roman nose, closed lips and a thick neck. The folds of his military garments sweep below his neck and are held in place by a circular disc on his right shoulder.

Activity 1

Begin by establishing some basic information about Hadrian. Use the internet and other reference resources that may be available to you. Remember to be mindful of the nature of the information that you use and evaluate its reliability.

Hadrian was a much-travelled emperor, so for the purposes of this exercise you may wish to focus your information gathering on how Hadrian came to power and the time he spent in Rome.

Don’t spend too long on this activity. An hour should be sufficient.

Discussion

We’re not going to rehearse the major events of the reign of Hadrian. The information you found out will depend on the resources you used.

It is interesting to note that Hadrian came to power as the adopted son of the emperor Trajan, of whom he was a distant relative. You may have picked up on rumours that Trajan’s wife (Plotina) might have played as much a part in this adoption as Trajan did. As the nominated successor to Trajan, Hadrian was part of a continuing dynasty; he did not seize power or gain it during civil war. In his turn, Hadrian too was at pains to secure the succession, ensuring that he had a suitable adopted son in place at his own death, thereby securing both the continuation of the dynasty and peace and stability for Rome and the empire.

We have already observed that, as emperor, Hadrian travelled the empire and was often away from Rome. You may have discovered that he was a particular fan of Greek culture and he was sometimes called the ‘little Greek’ (SHA, Hadrian 1). Hadrian was also a prolific builder, in both Rome and the empire, funding numerous constructions of varied kinds. You may have observed, too, that Hadrian has a bit of a mixed reputation – he appears to have been an able administrator, a military man and someone who was genuinely interested in the provinces, but in Rome itself he seems to have been unpopular, especially on account of executing some of his opponents.

We do not have extensive literary accounts of Hadrian’s reign. Suetonius (who was writing during that reign) ended his imperial biographies with Domitian. Tacitus and Pliny the Younger were both dead before Hadrian came to power. Dio Cassius’ account of Hadrian’s reign does survive, but only in abridged form. We also have a biography of Hadrian, but it is not without problems.

Activity 2

Read the following information on the Scriptores Historiae Augustae or SHA (also sometimes referred to as the Historia Augusta) and Dio Cassius.

Scriptores Historiae Augustae: The SHA is a collection of biographies of Roman emperors and some of their heirs, covering the years 117–284 CE. The text is incomplete and authorship is uncertain, but it purports to be the work of more than one hand, a group of authors known as the Scriptores Historiae Augustae. However, arguments have now been made that the SHA is the work of just one author. It remains unclear exactly when this author(s) was writing, or the purposes behind the work. The sources of information used by the author to compile the biographies are often uncertain, and there are doubts about the authenticity of some of the documents that are referred to.

Dio Cassius: Dio Cassius wrote, in Greek, an 80 book history of Rome from its foundation to 229 CE. He was writing during the late second and early third century CE, and was a distinguished senator, whose family came from Bithynia in Asia Minor. Dio Cassius lived through some troubled times and tyrannical emperors. His history of Rome is now incomplete, and the book which covers Hadrian (Book 69) is a summary produced by a later author (Xiphilinus). Dio Cassius would have been dependent on earlier written sources for his history of Hadrian, but the nature of these is not known.

Then read the following:

- Primary Source 1: SHA, Hadrian 9; 11; 13; 19; 21; 27. (Note that the entire text is reproduced, but for this activity you need to read only the chapters specified. You will read more of this source later in the course.)

- Primary Source 2: Dio Cassius 69, 2.5; 69.4–5.2; 69.7, 1–4; 69.23.

What strikes you about how these sources are written (for example their style and content)? How reliable do you think they are?

Discussion

What strikes us about the extracts from the SHA is that they are often like lists: lists of provinces that Hadrian visited and lists of buildings that he restored, with little by way of detail or expansion. In other places the material also seems disorganised. For example, in Chapter 21 the author talks about judges, freed slaves and slaves, then provides an anecdote about something Hadrian once said about a slave, before mentioning what Hadrian best liked to eat.

The extracts from Dio Cassius can also lack detail and contain anecdotes (such as Hadrian’s killing of Apollodorus). What is striking is that Dio Cassius tries to weigh up some good and bad aspects of Hadrian’s reign, ultimately noting that although in many respects Hadrian did a good job, he was still disliked; the emperor had a mild disposition, but also a murderous one. All this may suggest that the sources Dio Cassius used to write his own account may have presented mixed views of the emperor. It also suggests that Dio Cassius himself was not writing objective history; rather, his perspective was influenced by his own social position, as a member of the Senate, who had experienced life under some terrible rulers. To Dio Cassius, ‘mild’ Hadrian was not as bad as some other emperors.

Neither source would be regarded as completely reliable if judged by the standards expected of modern historians, that is to be objective, impartial and balanced. However, ancient authors did not adhere to such codes, and often saw history and biography as having important moralising and didactic elements

The extracts that you were asked to read from the SHA and Dio Cassius are just that: extracts, smaller parts of a larger whole. Here the aim was to give you a flavour of these works and the issues surrounding them.

The SHA is a problematic source. It is late in date, of uncertain authorship, of uncertain readership and at times can be inaccurate and muddled. On the plus side, the life of Hadrian is viewed as one of the more reliable of these biographies (Birley, 1976, p. 13) and it does contain a certain amount of factual information that can be checked against other sources, including Dio Cassius. The latter’s account of Hadrian’s reign, as we have seen, is also short on detail, and is coloured by the author’s own perspectives. Taken together, however, these works do give us a narrative structure for Hadrian’s rule, which we can complement with other evidence such as monuments, coins and inscriptions. And it is on this evidence that much of this course will focus.

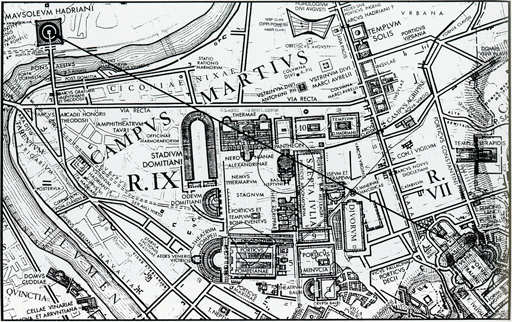

2 Hadrianic monuments in Rome

Hadrianic Rome is notable for its innovative architecture, which makes it a fascinating study for anyone interested in Roman buildings. One significant monument of Hadrianic Rome was the Pantheon, and this will be the main focus of this section. The Temple of Zeus Asklepios in Pergamum, an important city in Asia Minor, was modelled on the Pantheon and this illustrates a second reason for studying the monuments of Hadrianic Rome: the extent to which they inspired Roman architecture elsewhere in the empire.

Elements of Hadrianic innovation can also be found elsewhere in Italy. The most elaborate example is Hadrian’s imperial villa at Tivoli, but we can also find more mundane examples, such as the shops and houses constructed of brick-faced concrete in the harbour town of Ostia. Both Trajan and Hadrian used brick-faced concrete.

Like many emperors before him, Hadrian embellished the Forum and Campus Martius areas of Rome, leaving his mark on the monumental landscape of the city. Few Hadrianic monuments have survived, especially those in the Campus Martius, and the identification of some structures is disputed. You will study three Hadrianic monuments in this section, all of them temples: the Pantheon, the Temple of Deified Hadrian and the Temple of Venus and Rome. The main reason we have chosen these structures is that they are the three best-preserved Hadrianic monuments in Rome. But we have also chosen them because Hadrian is not the only emperor to be associated with these monuments, and that allows us to explore how public buildings could be used by an emperor to help legitimise his position as successor to the previous princeps. The Pantheon had earlier phases and later restorations; the Temple of Deified Hadrian was built by his successor, Antoninus Pius; and the Temple of Venus and Rome was rebuilt in the early fourth century CE by one of Rome’s last emperors, Maxentius (Claridge, 2010, pp. 119, 226). Something to think about as you work through this section is how and why emperors restored or rebuilt the monuments of their predecessors, or dedicated new monuments to them, particularly temples. Immortalising a predecessor who had a good reputation was one way in which an emperor could legitimise his authority. This phenomenon had its roots in the Republican practice of dedicating temples to act as memorials of individuals and to promote elite families (gentes). This section explores how Hadrian used monumental building to weave himself into Rome’s imperial history, and how his successor did the same.

Activity 3

Visit the interactive map and use the check-box to reveal the Hadrianic period and familiarise yourself with the monuments and buildings associated with Hadrian. Make yourself a timeline of Hadrianic monuments which contains the following information:

- the dates when the monument was built and restored – or rebuilt, if applicable (think about when this was in the context of Hadrian’s reign: for instance, was he in Rome when it was built? If so, how long had he been there and when did he make his next tour of the empire?)

- the names of individuals associated with the monument (such as the person who dedicated, built or rebuilt it, and the person or deities to whom it was dedicated)

- the reason for the construction of the monument

- the location of the monument

- the possible function(s) of the monument, where this is known.

Then, imagine that you have been asked to write an essay on Hadrian’s building programme at Rome. Use the information you have gathered to write a brief summary of his building activities and what they suggest about his motivations that you might use as part of an essay on this topic.

Spend no more than an hour on this activity.

Discussion

Hadrian restored or rebuilt at least two Augustan monuments: the Temple of Mars Ultor (in Augustus’ Forum) and the Pantheon (in the Campus Martius). He also designed and built the Temple of Venus and Rome and a mausoleum for himself. As we have noted, Antoninus Pius built the temple to the Deified Hadrian, following the practice of deifying and dedicating a temple to one’s predecessor. Hadrian did the same for Trajan when he became emperor, but the Temple of Deified Trajan built by Hadrian has not been conclusively identified.

All of these monuments are in either the Forum area or the Campus Martius, and most of them are temples. It was common practice for an emperor to be deified after his death and a temple built to honour him, usually by his immediate successor and usually in one of the Fora. Other members of the imperial family could also be deified (you will study an example later in this course). The practice of deification helped legitimise the rule of both the deceased emperor and his successor, indicating that imperial rule was divinely ordained. Building a temple ensured that the populace had a constant reminder of this, as well as demonstrating the piety and beneficence of the current emperor. You will study the topic of imperial deification more fully in Section 3 of this course.

2.1 Introducing the Pantheon

Some of the monuments associated with Hadrian pre-date him, while others belong to a later period, and most were restored by multiple emperors. The most iconic of these monuments is the Pantheon (Figure 2).

This is an oblique aerial photograph of a built-up area shown in colour. The focus is a large circular building with a domed roof. The lower half of the roof is stepped and there is a circular opening at the top in the centre.

Attached to the front of the building is a porch. Eight Corinthian columns support a plain pediment and the edges of four further columns are visible beyond them.

The dentils at the sides of the pediment can just be seen. Below them on the architrave is a Latin inscription.

Buildings surround the wedge of land where the circular building stands. A street runs either side of the building. An obelisk capped with a cross decorates a fountain standing on a low stepped base in the centre of an open pedestrianised space in front of the porch.

The Pantheon survives due to its novel architectural design and because it was transformed into the Church of St Mary of the Martyrs in 608 CE. You might assume that such a well-preserved building is well understood, but the Pantheon illustrates the point that while many of Rome’s ancient monuments survive – in this case, almost intact – there is much we don’t know about their construction, chronology, meaning and purpose.

Activity 4

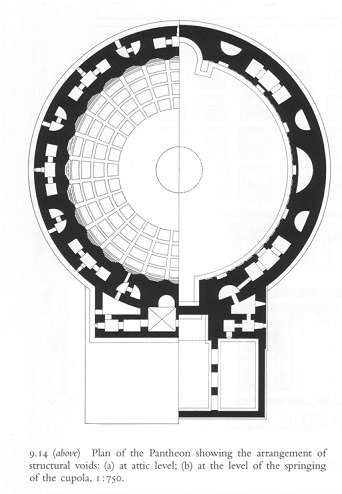

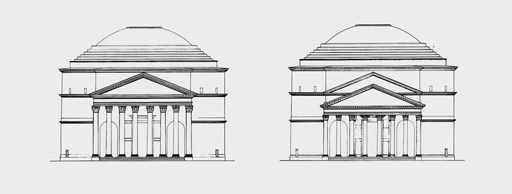

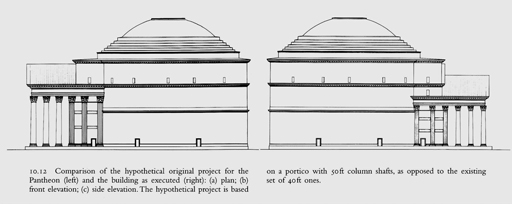

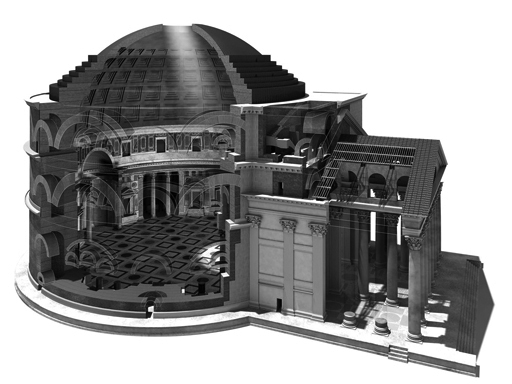

Listen to the audio recording ‘The Pantheon’, in which Mark Wilson Jones discusses the disputed aspects of the Pantheon: its date, phasing and design coherence, and look at the accompanying images.

As you listen to the audio recording, make some notes in answer to the following questions:

- What do we still not know about the Pantheon? Does it surprise you that a standing monument such as this one is not fully understood?

- How was the Pantheon constructed? What was novel about its design and construction? How does Wilson Jones explain the architectural incongruities?

- What debates are there about the meaning and purpose of the Pantheon?

Transcript: The Pantheon

Discussion

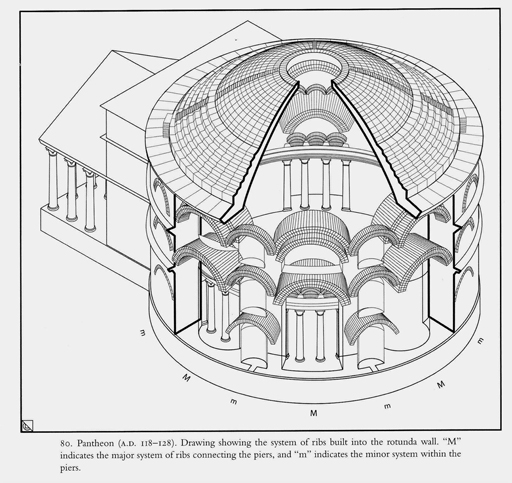

- The Pantheon as we see it today has inspired architects for almost the last 2,000 years. It is a well-studied monument, and yet we don’t know what the building was used for, why its structure lacks architectural cohesion, or who designed and built it. The inscription tells us it was built by Agrippa, but brick stamps date it to Trajan and Hadrian. Wilson Jones explains how the material evidence, both architectural and archaeological, has been interpreted and reinterpreted since the nineteenth century. The monument that stands today replaced one which burned down in 110 CE and may be the second or third Pantheon to have been built on the site.

- The Pantheon is often referred to as a temple to all the Roman gods (‘pantheon’ derives from the ancient Greek for ‘all the gods’) and certain features are suggestive of temple architecture, such as the pediment on the portico. But it also has unusual features, such as the unsupported domed roof with its oculus, which gives a particular perspective not found in other Roman buildings. Wilson Jones also discusses the possibility that the Pantheon may have been planned as a temple to Augustus, and he explores the relationship the building has with the other Augustan monuments in the Campus Martius.

- Debates about the architectural incongruities, phasing, meaning and purpose of the Pantheon continue. How convincing did you find the arguments put forward by Wilson Jones? Perhaps listen again to the recording and note what evidence he uses to construct and support his ideas.

You may have been more convinced by some hypotheses and arguments than by others. There are no right or wrong answers here, as long as your point of view is supported by evidence from the various types of primary sources we have for the Pantheon. If you are interested in pursuing some of the academic arguments presented in the audio recording, you will find suggestions in the list of further reading associated with this course.

Exploring the Pantheon further

The Hadrianic Pantheon is an example of Roman architecture at its most ingenious, partly because of the construction of the dome but also because of the ability to improvise, which Wilson Jones argues is what we see in the construction of the porch. Several hypotheses have been mooted to explain the aesthetic disharmony caused by the short columns which support the portico. The columns intended for the Pantheon may have been used by Hadrian in the Temple of Deified Trajan instead. Fifty-foot (15-metre) columns were difficult to quarry and transport, and even with exclusive control over the quarry from which the stone came (Mons Claudianus, in Egypt’s eastern desert) the emperor might not have been able to acquire the necessary components for both the Pantheon and the Temple of Deified Trajan. Time may also have been a factor. With Hadrian spending so little time in Rome, there were small windows of opportunity in which to complete – and celebrate the opening of – new public buildings (see also Wilson Jones, 2013, pp. 44–5).

The Pantheon is one of the few monuments to survive from the Hadrianic period, despite others in the vicinity having also been restored by him (SHA, Hadrian 19). What is unusual is that rather than replacing the dedicatory inscription with one which named him, Hadrian kept (or more likely recreated) the Agrippan inscription, reminding the populace of the original dedicator. At first this gives the impression that Hadrian was being modest, as he was not promoting himself. Contrast this with the second inscription on the façade, which commemorates the restoration of the Pantheon by Septimius Severus and Caracalla in 202 CE (CIL 6. 896). However, by reminding people of the Pantheon’s Augustan origins Hadrian was subtly associating himself with the first emperor. This helped him legitimise his position as ruler by suggesting that he was part of the natural succession of (deified) emperors. It is worth noting that Domitian had restored the Pantheon following a fire in 80 CE (Dio Cassius 66.24.2), but Hadrian chose to name the original dedicator of the temple, Agrippa, rather than linking himself with an unpopular emperor. In addition, the unique architecture of the Pantheon, with its vast dome, was a more subtle way for Hadrian to leave his signature on the building than an inscription might have been – and it would have been more easily ‘read’ by a largely illiterate population.

The Pantheon was embellished with a wealth of exotic materials. The porch was supported by columns of grey granite from Mons Claudianus and pink granite from Aswan (although most of the pink granite columns that survive today are seventeenth-century restorations). Those columns had bases and capitals of Pentelic (Greek) white marble, traces of which also remain on the exterior panelling. Yellow Numidian marble from Chemtou in Tunisia was used for the steps. Much of the interior decoration has been restored, but traces remain of Numidian yellow, as well as Phrygian purple and Lucullan black, both from different parts of Turkey, and roundels of red porphyry from Egypt.

The granite columns intended for use in the Pantheon may have been appropriated by Hadrian for the Temple of Deified Trajan. Coming from Mons Claudianus, these grey granite columns represented the southernmost frontier of Rome’s vast empire. Egypt had been an imperial province since its annexation by Augustus following the defeat of Antony and Cleopatra at Actium in 31 BCE. Consequently, the Egyptian granite columns, which no one but the emperor was entitled to use, also represented the far-reaching power of the emperor.

The Pantheon was a showcase of imperial power and the extent of the empire. In Hadrian’s case the Pantheon, and his other building projects, reflected his penchant for bringing aspects of the empire into Rome. This is nowhere more apparent than in the architecture and sculpture of Hadrian’s villa at Tivoli, but the Temple of Venus and Rome, which we will look at a little later in this course, is another good example.

Next in this section you will study the written sources for the Pantheon, to see what they can tell us about its meaning and purpose. Remember that our main sources for the Hadrianic period, Dio Cassius and the SHA, were written much later and are not entirely reliable.

Activity 5

Read the following sources:

- Primary Source 1: SHA, Hadrian 19. For this activity just read from ‘Although he built countless buildings …’ to ‘… the names of their original builders’

- Primary Source 3: Dio Cassius 53, 27.1–4.

What do the sources tell us about the meaning and purpose of the Pantheon? What was it used for? Did its meaning and purpose change in its different phases?

Discussion

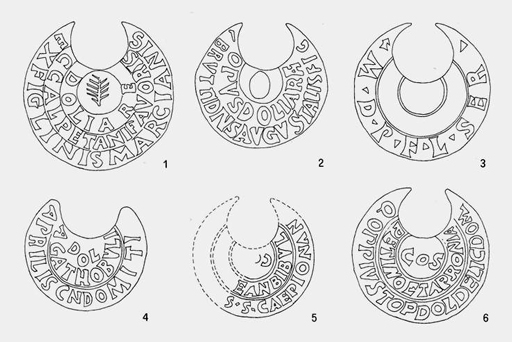

The extract from the SHA confirms that Hadrian restored the Pantheon and other Agrippan monuments in the Campus Martius, and notes that he ‘dedicated all of them in the names of their original builders’ (SHA, Hadrian, 19.11). This corresponds to the evidence we have of the Agrippan inscription on the porch, as you saw in Activity 4 – M(arcus) AGRIPPA L(ucius) F(ilius) COS TERTIUM FECIT: ‘Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, three times consul, made this’. But the SHA tells us nothing about the meaning or purpose, and for that we must turn to Dio Cassius.

However, Dio Cassius seems unsure of the meaning of the Pantheon, though he does say the building was decorated with statues of Rome’s ‘many gods’ (53.27.2). He does not specifically describe the Pantheon as a temple. His account is also somewhat anachronistic, as he refers to Agrippa’s building projects in the Campus Martius, but goes on to describe the dome of the Hadrianic Pantheon (‘because of its vaulted roof, it resembles the heavens’: 53.27.2). In other words, his opinion of the meaning of the building is based on the structure he visited in his lifetime, rather than the original Agrippan building. This may lead us to question the reliability of his interpretation. The rest of Dio Cassius’ account suggests that Agrippa’s Pantheon was intended as a temple for worship of the emperor, but that Augustus balked at this. Nevertheless, statues of his divine ancestors, Venus, Mars and ‘the former Caesar’ (Divus Iulius), were placed in the Pantheon, along with statues of Augustus and Agrippa in the ‘ante-room’ – probably the porch (53.27.3). This collection of statues is not dissimilar to that found in Augustus’ Forum. An association with the imperial cult is perhaps corroborated by a later inscription (CIL 6. 2041) which reports that the Arval Brethren, who made regular vows for the well-being of Rome and the imperial family, met in the Pantheon in 59 CE.

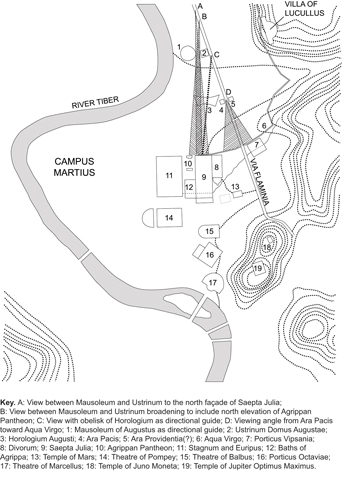

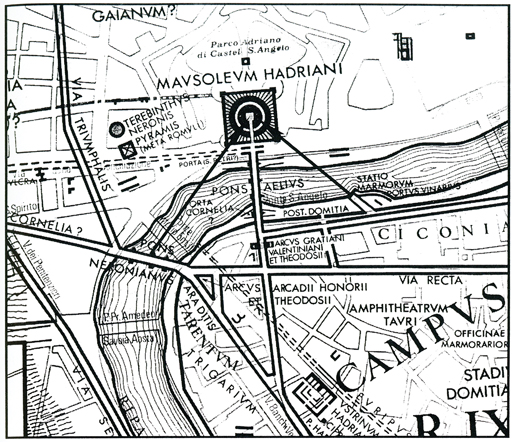

Ultimately, while we know little about the design and function of the Agrippan Pantheon, it is clear that it was an integral part of Augustus’ appropriation of the Campus Martius. Figure 12 shows that there was a direct line of sight from the entrance of Agrippa’s Pantheon to Augustus’ mausoleum (which you’ll study in Section 3). The Campus Martius was stamped with Augustus’ authority and legacy, much of which harked back to the myths of Rome’s foundation. In rebuilding the Pantheon, and keeping its original inscription, Hadrian wove himself into the Augustan narrative, although by then the line of intervisibility had been blocked by later buildings. It is perhaps unsurprising, though, that we find Hadrian’s mausoleum in the vicinity of both monuments.

Dio Cassius describes Hadrian’s use of the Pantheon, with an emphasis on public business rather than religious ritual:

He transacted with the aid of the senate all the important and most urgent business and he held court with the assistance of the foremost men, now in the palace, now in the Forum or the Pantheon or various other places, always being seated on a tribunal, so that whatever was done was made public.

This is a black, white and greyscale plan. There is a key across the bottom. No scale or compass is provided.

To the left is the River Tiber. The river meanders through the plan from top to bottom. From the centre at the top the river curves gently towards the right and then back in a large sweeping curve towards the left. In the lower half of the plan it curves towards the right again before bending back and exiting at the bottom. An island can be seen in the centre of the lower bend. Four sets of short narrow parallel lines form gaps in the river in the lower half of the plan. One of these goes through the island. These represent bridges across the river.

Contour lines are shown on both sides of the river. To the left these are restricted to the bottom left-hand corner. A larger set of contour lines indicating several hills are shown down the length of the right-hand side.

The space formed by the large central bend of the River Tiber is labelled CAMPUS MARTIUS. Between this space and the contours on the far right there is a series of numbered shapes. An un-numbered building is labelled VILLA OF LUCULLUS. This can be seen parallel to the contours at the top right.

Two parallel lines labelled VIA FLAMINIA begin at the top of the plan a little way to the right of the river. They run at an angle down towards the right. When they reach the contours they follow them. The letters A to D can be seen alongside the upper part.

The key names a series of 19 structures located in a vertical strip between the river and the contours. They are grouped within a roughly diamond shape with the lower numbers towards the top, the middle numbers in the centre and the higher numbers towards the bottom. The structures are:

1 Mausoleum of Augustus as directional guide.

2 Ustrinum Domus Augustae

3 Horologium Augusti

4 Ara Pacis

5 Ara Providentia (?)

6 Aqua Virgo

7 Porticus Vipsania

8 Divorum

9 Saepta Julia

10 Agrippan Pantheon

11 Stagnum and Euripus

12 Baths of Agrippa

13 Temple of Mars

14 Theatre of Pompey

15 Theatre of Balbus

16 Porticus Octaviae

17 Theatre of Marcellus

18 Temple of Juno Moneta

19 Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus

There is a key for the letters A, B, C and D which lie along the upper part of VIA FLAMINIA.

A is located at the top of the plan on the VIA FLAMINIA. The key indicates A is the view between Mausoleum and Ustrinum to the upper façade of Saepta Julia. The point of an elongated triangle filled with diagonal lines from top right to bottom left begins at A and spreads out as it proceeds down. Near the top it runs between 1 Mausoleum of Augustus and 2 Ustrinum Domus Augustae. It then goes through the left-hand side of 3 Horologium Augusti. At the lower end it covers the width of 9 Saepta Julia.

B is located just below A on the VIA FLAMINIA.The key indicates B is the view between Mausoleum and Ustrinum broadening to include north elevation of Agrippan Pantheon. The point of an elongated triangle filled with diagonal lines from top left to bottom right begins at B and spreads out as it proceeds down. It runs between 1 Mausoleum of Augustus and 2 Ustrinum Domus Augustae. It then goes through the left-hand side of 3 Horologium Augusti. At the lower end it covers the left half of 9 Saepta Julia and the right half of 10 Agrippan Pantheon.

A hatched area where the diagonal fill of both triangles meet is shared by both A and B. This covers the left-hand side of 9 Saepta Julia.

C is located further down the VIA FLAMINIA at the lower right–hand edge of 2 Ustrinum Domus Augustae. A line of black dots runs diagonally from C to the centre of 9 Saepta Julia.

D is situated on the VIA FLAMINIA between 4 Ara Pacis and 5 Ara Providentia (?). A hatched triangle begins at D. Its bottom right corner is in the centre of 7 Porticus Vipsania. The left-hand corner almost reaches the top right-hand corner of 8 Divorum.

Curved lines of dots link several of the features on the plan. One dotted line begins at the river and almost touches the lower edge of 1 Mausoleum of Augustus crosses VIA FLAMINIA towards a gap in the contours where it doubles back down to the centre of 9 Saepta Julia. A second short line of dots links the lower right-hand corner of 8 Divorum with 13 Temple of Mars and then to VIA FLAMINIA.

A little further down VIA FLAMINIA a third line of dots links it with 15 Theatre of Balbus, 16 Porticus Octaviae, 17 Theatre of Marcellus and then down to the lower bend of the River Tiber.

This has much in common with the functions of the Imperial Fora, where divinely sanctioned public business took precedence. Both the Pantheon and the temples of the Imperial Fora seem to have represented the legitimacy of imperial rule, as the gods watched over the multifarious aspects of government. They were also arenas in which the emperor could remind Rome’s populace of the extent of the empire, and his personal control of it.

Imperial Rome, and Hadrianic Rome in particular, was a place that was embellished and influenced by the riches of empire. The materials used in the construction and decoration of the Pantheon show that Rome and the empire were integrated rather than separated, but they also acted as reminders of the power and wealth of the emperor. The following sections continue to explore these themes.

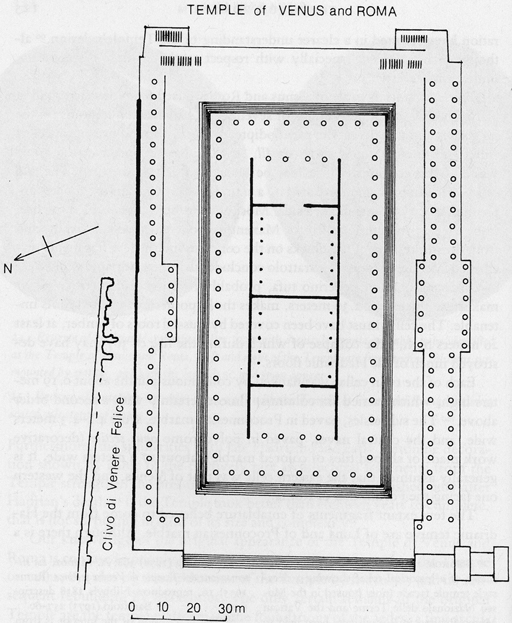

2.2 The Temple of Venus and Rome

In this section we’ll consider another of Hadrian’s building projects: the Temple of Venus and Rome.

This is a colour photograph of an ancient monument. It shows a horizontal line of six broken columns of varying height standing on a strip of grass.

Behind the columns to the left is the tall apsidal end of a large ruined building. The open domed part of the apse is decorated with a lattice pattern with a smaller diamond shape in the centre of each space. A niche can be seen in the curved wall below.

A small portion of the side wall of the building is visible adjoining the apse to the far left. Sections of broken columns can be seen lying on the ground in front of the apse.

The walls of other tall buildings can be seen close to the apse on the right of the photograph.

Activity 6

Go to the interactive map to locate the Temple of Venus and Rome and establish some basic facts about it:

- where was it located?

- what building was on the site before the temple?

- when was it dedicated? (Think about when this was in the context of the periods when Hadrian was in Rome rather than travelling around the empire.)

- which emperor restored the temple?

Discussion

The temple was located between the Roman Forum and the Colosseum valley, so its construction enabled Hadrian to put his mark on this central public area of the city. It was what Hadrian built instead of another Imperial Forum, and it was his most significant building project in the Forum area. With the Temple of Deified Trajan he had sealed off the Imperial Fora, which had no further space for expansion in any case, as they were by then abutting the Campus Martius. So, Hadrian built at the opposite end of the Forum Romanum, in an area previously dominated by Nero’s Domus Aurea. The Colossus of Nero (which gave the Flavian amphitheatre its nickname) had to be moved to make way for a huge artificial platform (145 by 100 metres). The highly visible Greek-style temple was built on top of this.

Building took time. The temple was dedicated by Hadrian on 21 April 121 CE, one of the few occasions when he was in Rome, but was not completed until at least 135 CE. It may not have been completed by Hadrian at all, but by his successor, Antoninus Pius.

The visible remains of the temple date to a later phase. It was rebuilt by Maxentius after a fire in 307 CE, so it is difficult to visualise the Hadrianic structure, especially as the coffered concrete vaults remind us of the domes for which Hadrian was famous, but actually belong to the restoration.

Activity 7

Read the following two sources, and then answer the questions below:

Primary Source 1: SHA, Hadrian 19: from ‘With the help of the architect …’ to ‘… the architect Apollodorus’.

Primary Source 2: Dio Cassius: 69.4.

- What evidence do we have that Hadrian was the architect of the Temple of Venus and Rome?

- What criticisms did Apollodorus make of his design?

- What does this tell us about the way later authors, such as Dio Cassius, perceived Hadrian’s relationship with his peers?

Discussion

The SHA describes how Hadrian oversaw the moving of Nero’s Colossus and, having rededicated the statue to the sun, Helios, commissioned Apollodorus to design a second statue to represent the moon. This suggests that the temple was Hadrian’s project, but there is no direct evidence that he was the architect. Instead, we read that he employed at least two other architects to realise the project.

If Dio Cassius can be believed, Hadrian and Apollodorus were competitive and keen to criticise each other’s ability as architects, and their artistic differences ultimately led to Apollodorus’ death. That this anecdote is reported by Dio Cassius reveals how hostile the senatorial classes remained to Hadrian after his death. However, there may be a grain of truth in the story: the reported quote ‘draw your gourds’ may refer to the complicated concrete domed structures Hadrian was sketching as part of his designs for the villa at Tivoli, and perhaps also refers to the design of the Pantheon, which was completed around the time that work began on the Temple of Venus and Rome. Apollodorus’ specific criticisms of the plans for the temple were that it was not elevated enough and the cult statues were out of proportion with the cella.

It is also possible that Apollodorus criticised Hadrian’s temple design because it was Greek in style (and one might expect a temple to the goddess Roma to be Roman in style). It sat on a low podium, with a few steps, and was surrounded on all sides by a colonnade, all of which are Greek features. You may remember that Hadrian’s love of Greece and Greek culture, his philhellenism, won him the nickname graeculus: ‘little Greek’ (SHA, Hadrian 1.5). The temple actually comprised two Roman-style temples placed back-to-back – one dedicated to Venus, the other to Roma – and this is what created the overall effect of a Greek temple.

The temple design therefore represented the emperor’s love of both Greece and Rome, but what was the significance of Hadrian dedicating a temple to Venus and Rome?

His choice of deities linked Hadrian to Augustus, the Julian gens (clan) and their ancestral deity, Venus, as well as to the city itself, in the guise of the goddess Roma. Although Roma features on one of the relief panels of the Augustan Ara Pacis, and had been personified as a goddess in the eastern Mediterranean for some time, the temple was the first to be dedicated to Roma in Rome itself. For a peripatetic emperor like Hadrian, this commemoration and personification of Rome may have been an attempt to show the Senate and the Roman people that he was devoted to the capital city, despite his frequent absences from it.

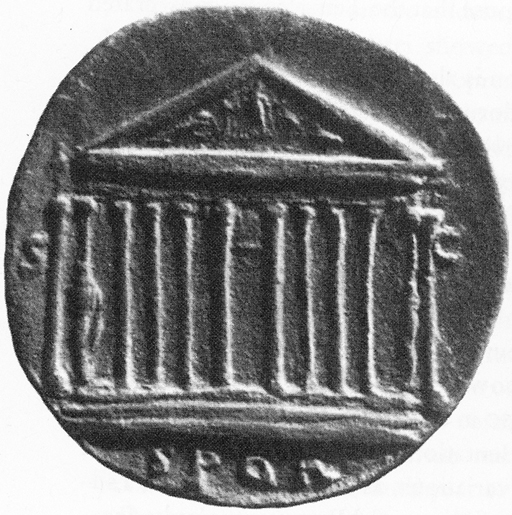

Hadrian dedicated the temple on 21 April, the date of the Parilia festival, on which (according to Roman tradition) in 753 BCE Romulus had founded the city of Rome. Having dedicated the temple, Hadrian renamed the festival the Romaia. In so doing, he revitalised the festival which celebrated Rome’s origins and the common identity of the Roman people. Coins proclaimed a new Golden Age (saeculum aureum), making Hadrian the new Romulus. Augustus had done something similar (and had almost taken the name Romulus).

By dedicating the temple to the goddess Roma, Hadrian demonstrated his devotion to the city and emphasised the power of Rome within a vast empire. The temple’s design reflected the personal interest he took in the empire as a whole, and this would particularly have been the case if Hadrian were the architect of the temple. The Temple of Venus and Rome therefore reinforced and celebrated the traditions and past of Rome, but also made a visual reference to the wider empire which would have been recognised by Rome’s inhabitants and visitors to the city.

Activity 8

To complete your study of the Temple of Venus and Rome, turn to Reading 1. This is a section from Mary Boatwright’s book Hadrian and the City of Rome. Read from the start to ‘… probably of peperino’ (p. 128), and then answer these questions:

- What evidence (written and material) does Boatwright use to discuss the Temple of Venus and Rome?

- How does Boatwright use the archaeological evidence to construct her interpretation of the temple?

- How convinced are you by her analysis?

Discussion

- Boatwright draws on a range of archaeological evidence to construct her argument: the architectural remains of the temple (complicated by the restoration by Maxentius), coins and brick stamps. She is dismissive of Dio Cassius’ anecdote about Hadrian and Apollodorus and therefore relies almost entirely on archaeological evidence. She also uses secondary sources, drawing on earlier publications to provide information about aspects of the temple which were recorded in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but have since been lost.

- Boatwright begins by establishing the dates of the temple’s construction, using a combination of different types of evidence: the comparatively rare brick stamps, coins and literature. When she studies the architecture, the first thing Boatwright does is to identify surviving Hadrianic elements in the Maxentian restoration of the temple. With this architectural foundation she is able to construct an interpretation of the Greek and Roman elements (which include aspects of architectural style, materials and decoration).

- How convincing you find Boatwright’s argument will be quite personal, but do pay close attention to the way she weaves together the different sources of evidence. A significant part of her argument is that the temple was completed by Hadrian’s successor, Antoninus Pius. How does this compare with the argument made by Mark Wilson Jones in the audio recording ‘The Pantheon’ that the Pantheon was begun by Trajan and completed by Hadrian? Note that both scholars use brick stamps as evidence for their interpretation of the chronology of the buildings. This is in part because both of them consider these to be more reliable evidence than the written sources.

2.3 The Temple of Deified Hadrian

Your study of Hadrianic monuments in Rome concludes with another temple associated with his successor, Antoninus Pius – the Temple of Deified Hadrian.

This is a colour photograph showing the front part of a Classical building with a modern building attached to it on either side. It is seen at an angle from the right.

A row of eleven fluted columns with Corinthian capitals support a decorated entablature.

A wall with a door is visible through the columns at the back.

The roofs of the modern building follow the upper lines and design of the Classical entablature. The upper panelled part is modern and links the Classical structure to the modern ones either side of it.

Figure 14 shows what survives of the temple. There are 11 Corinthian columns of Proconnesian marble and part of the cella wall, as well as part of the lower entablature. Excavations behind the railings have revealed part of a podium of local peperino tufa. There is no inscription to identify the temple, but the architectural style belongs to the late Hadrianic or early Antonine period. This, along with the temple’s location in the Campus Martius, has led archaeologists to identify it as the Temple of Deified Hadrian, which Antoninus Pius dedicated in 145 CE. Another large temple precinct nearby may be that of Hadrian’s mother-in-law, Matidia, and her mother (Trajan’s sister), Marciana, who were deified after their deaths (see Section 3). A series of marble panels found in the vicinity may have decorated the Temple of Deified Hadrian or another public building nearby. These are interesting because they are carved with personifications of cities and peoples of the Roman empire, alternating with images of military and naval trophies (see Hughes, 2009 for discussion).

The harmonious composition we see on the Hadrianeum represented the empire at peace and running smoothly. Mary Boatwright presents a similar idea in her discussion of the Temple of Venus and Rome, part of which you studied as Reading 1.

In the iconography of both temples the emperor may have been trying to create a positive image of the authority of Rome. Nevertheless, these temples and others were a constant reminder of who was in control in Rome and in the empire: the emperor.

Section 2 has focused on temples associated with Hadrian. In the final part of this course on Hadrianic Rome you’ll explore how Hadrian wove himself and the imperial family into the fabric of the city even after their deaths.

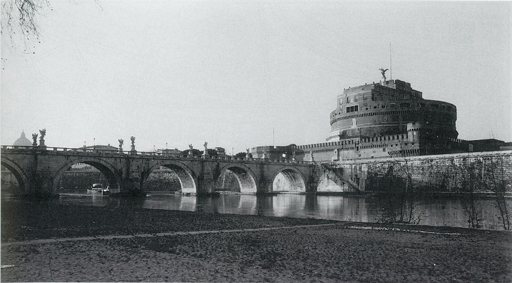

3 Death, divinity and the emperor

One of the most prominent monuments on the skyline of modern Rome is the mausoleum of Hadrian, known today as the Castel Sant’Angelo. In this section we will investigate this impressive monument and assess its importance, but also think more widely about why commemoration after death mattered so much to emperors, and how this was linked to divine rights to rule.

Every new reign began with a death: that of the old emperor. In dynastic succession the new emperor derived his power and authority to rule from his predecessor, and thus it served him well to honour the dead emperor with a suitable burial and commemoration. In Rome there was the added incentive that the dead emperor might be given divine honours and be thought to reside among the gods. We have already seen the close relationship that Rome’s rulers and emperors forged with the gods, for example by dedicating and restoring temples. It was important that Rome’s rulers appeared to be pious and blessed by the gods, and some favoured certain deities, even claiming familial connections with them. At this stage it is important to note that the people of Rome did not subscribe to some sort of divine kingship. Although an emperor might cultivate a religious aura and close associations with deities, the living were not regarded as gods. Those who blurred the distinctions between the human and the divine, such as the emperor Domitian who, allegedly demanded to be called ‘Our Master and our God’ (Suetonius, Domitian 13.2), were seen as deluded and as bad rulers. However, at death it was possible for an emperor to be elevated to divine status.

The process of an emperor becoming a god is termed ‘apotheosis’. It involved elaborate funeral rites in which the spirit of the emperor was thought to fly heavenwards from the pyre (an eagle might be released to represent this ascent), but also a formal vote by the Senate confirming that the dead emperor had been consecrated as a god (Hekster, 2009; Price, 1987). Other members of the imperial family, including women, were sometimes granted divine honours, and this was to become increasingly the case in the second century CE. An emperor could thus find himself styled as the son of a god and have other relatives who were divine: these were no small accolades.

This is a colour photograph of a marble sculpture, showing the head, shoulders and upper chest of a young man shown against a dark background. The man is naked and is looking down slightly to the viewer’s right. He has almond-shaped eyes, angular eyebrows, a long straight nose and full lips. His thick wavy locks of hair cover his ears.

The bust is attached to a small low circular drum with a carved collar at the top and bottom. It has two lines of inscription in Greek, one on the upper collar and one in the middle.

Hadrian was someone who seems to have been particularly aware of the significance of divinity. Like many of his predecessors, Hadrian favoured certain gods, promoting connections between himself and religion (see Section 2) as a sign that he was divinely sanctioned to rule, but the emperor also surrounded himself with gods of his own making. In this respect he is perhaps most famous for how he treated Antinous after his death. Antinous was a young man, a great favourite and a probable homosexual partner of Hadrian, who drowned in the Nile in mysterious circumstances in 130 CE (Dio Cassius 69.11.4; SHA, Hadrian 14.11). Hadrian seems to have promoted a cult of Antinous that became popular across the empire, and the emperor thought of Antinous as a god. However, Antinous was not formally deified in Rome by the Senate. He was not a member of the imperial family and his deification, though it may have been important to Hadrian, was informal. This stands in stark contrast to the treatment of members of Hadrian’s family: people through whom he derived and confirmed his right to rule.

In 117 CE the emperor Trajan died in Cilicia, in Asia Minor, and his successor, Hadrian, arranged for his remains to be returned to Rome accompanied by Plotina (Trajan’s wife), Matidia (Hadrian’s mother-in-law) and Attianus (the Praetorian Prefect) (SHA, Hadrian 5.9–10). His remains were placed in a golden urn (Eutropius 8.5.2.3) and interred in the base of Trajan’s Column (Dio Cassius 69.2.3), which still stands in Rome. The column is situated in Trajan’s Forum. It stands more than 44 metres high, on a base sculpted with weapons and trophies. On the shaft of the column is a spiralling narrative frieze, showing scenes from the Dacian Wars. A spiral staircase runs through the interior of the column and in antiquity would have given access to a viewing platform. Above this platform originally stood a statue of Trajan. It is unclear whether the column was built with the purpose of being Trajan’s tomb, or whether this decision was made later, or under Hadrian (Davies, 2000, p. 32). It has been suggested that the narrative reliefs, for which the column is famous, were added by Hadrian (Claridge, 1993). This is not a proposition accepted by all, but what we can say is that, under Hadrian, work continued on Trajan’s Forum and that Hadrian added, or completed, a temple to his now deified adoptive father (SHA, Hadrian 19.9), although the exact location of this is yet to be confirmed (Claridge, 2007).

In 119 CE Hadrian’s mother-in-law, Matidia, died. Her maternal uncle was the emperor Trajan. After the death of her father she was brought up in Trajan’s household. Matidia was also a second cousin to Hadrian and her daughter Sabina married him in 100 CE.

Activity 9

Look at Figure 16, a coin commemorating Matidia. Then read Primary Source 4, Hadrian’s speech on Matidia after her death.

This silver coin, issued during the reign of Hadrian, shows a bust of Matidia, facing right, with her hair worn up and wearing a diadem. The bust is encircled by the words DIVA AVGVSTA MATIDIA (‘the divine Augusta Matidia’). Augusta was the female equivalent of the name Augustus – and thus an honoured title for an emperor’s female relatives. On the reverse of the coin an eagle is depicted and the word CONSECRATIO (‘consecrated’) appears.

Study the coin, read the speech and, paying due attention to context, identify how Matidia was honoured after her death – and why.

This is a colour photograph of two sides of a silver coin shown against a black background. The obverse is to the left and the reverse to the right.

The obverse shows the head of a woman facing right. The folds of her garments are draped around her neck. Her hair is pinned in a thick coil at the back and she is wearing a diadem. An inscription runs in a deep arc around her. It reads DIVA MATIDIA AVGVSTA. A worn arc of raised dots can be seen along the edge of the coin at the top.

The reverse shows an eagle standing on a line across the bottom arc of the coin. The bird is leaning towards the right with its head turned towards the left. It is raising its wings.

An arc of inscription frames the eagle. It reads CONSECRATIO. An arc of raised dots is visible on the left-hand side of the coin.

Discussion

The role of the original inscription is unclear. But the coin, with its portrait of Matidia on one side and an eagle on the other, is clear evidence that Matidia was deified. The coin describes her as divine, while the eagle suggests her flight to the heavens (from the funeral pyre), and thereby verbally and visually declares her consecration as a goddess. Coins, with their images and texts, and their wide circulation, were often used to commemorate important events.

We do not know why the speech was recorded, or how and exactly where it was displayed. But the fact that it was recorded suggests that the speech was an important event, with its high praise for Matidia from the emperor, and possibly related to her consecration. According to the speech, Hadrian was fond of his mother-in-law. She was like a daughter to Trajan and a loyal wife to her husband. She was a modest woman who did not try to exploit her connections with powerful people. Hadrian was distressed at her decline and spoke of his grief at her death. The speech may have ended with a recommendation that Matidia be deified.

Hadrian might well have loved and respected his mother-in-law, but it undoubtedly was to his advantage to be seen to be honouring his Trajanic adopted family. Hadrian was now the son of a god (Trajan) and married to the daughter of a goddess, which all helped to legitimise his position. So as well as remembering Matidia, Hadrian was at the same time promoting an image of harmony and virtue within his own family, through his female relatives.

Hadrian also established a temple complex to Matidia and her mother Marciana (deified under Trajan) in the Campus Martius. Evidence for it is limited (Boatwright, 1987, pp. 58–62), but it was the first in Rome to be dedicated to a deified woman or women.

Trajan’s wife, Plotina, also appears to have been deified at her death in c.123 CE. Then in 136/7 CE Hadrian’s wife, Sabina, died and she too was deified. Hadrian erected a monumental altar in her honour, probably on the northern Campus Martius, to which a large marble relief panel may well have belonged.

Activity 10

Study the following sources (as you look at the images, make sure you read the descriptions below too):

- Primary Source 1: SHA, Hadrian 11 from ‘Septicius Clarus, prefect of the guard …’ to the end.

- Figure 17: relief panel depicting Sabina and Hadrian. This marble relief panel, now in the Museo del Palazzo dei Conservatori in Rome, is believed to have come from an altar dedicated to the deified Sabina. In the relief a winged female figure soars upwards, carrying Sabina on her back. A seated image of Hadrian, with a man standing in attendance, occupies the bottom right of the relief. To the bottom left is a semi-nude male figure, thought to be a personification of the Campus Martius, the area of Rome where the altar was located.

- Figure 19: coin commemorating Sabina. This silver coin, issued during the reign of Hadrian, shows a bust of Sabina, facing left, with her hair worn up, wearing a diadem, with the words SABINA AVGVSTA. On the reverse of the coin are the words CONCORDIA AVG(usta), and the figure of Concordia leaning on a column, holding a patera and two cornucopias. (Concordia was a Roman goddess who embodied harmony in marriage and society.)

How is the relationship between Sabina and Hadrian represented in these sources?

This is a colour photograph of a relief within a carved architrave.

A man with a close-cut beard is sitting on a stool facing left with his left hand resting on his lap. His right hand is raised with his closed palm towards him and index finger pointing upwards. He is wearing a toga and a wreath. His left foot is on the ground in front of him. His right foot is drawn back towards his stool. He is shown larger than the other figures in the scene.

A bearded man stands behind him and a bare-chested young man reclines on the floor at his feet. His back is to the viewer. His right elbow rests on his thigh and his hand is raised as he turns his head towards the seated man to the right.

In the background to the left is a burning pyre. A winged female figure is shown rising diagonally from it. Her hair is pinned up and her breasts and right thigh are visible. She is holding a flaming torch and is looking up to the left at a woman who is riding on her back. The woman is holding the folds of her veil out towards the left. Her other hand rests on the shoulder of the winged figure and she looks towards the right as she is carried upwards.

This is a colour photograph showing two sides of a silver coin against a black background. The obverse is on the left and the reverse on the right.

The obverse shows the head and shoulders of a woman facing left. The folds of her garments drape around her neck. She has a prominent nose. Her hair is swept up in an elaborate coil and she is wearing a diadem. There is an inscription either side of her. To the left is SABINA and to the right is AVGVSTA. An arc of raised dots runs around the coin. It is worn in places.

The reverse shows a standing female figure facing left. In her right hand she is holding a shallow dish out in front of her. In her left is a double cornucopia.

There is an inscription either side of her. It reads CONCORDIA AVG. A short arc of raised dots runs around the edge of the coin to the right.

Discussion

According to the SHA, Hadrian and Sabina’s marriage was not a happy one. There were rumours of impropriety on Sabina’s part, and Hadrian found her ill-tempered and irritable. For his part Hadrian was a little too interested in other people’s lives, and far from faithful. All this may be little more than gossip, but if so it still became part of Hadrian’s legacy. Along with the other women of his household, Sabina does seem to have been important to Hadrian’s image. You may have noted in your earlier research that Hadrian and Sabina were childless, and this could have created anxieties about who would succeed the emperor. Nevertheless, the women of the imperial household provided connections to Hadrian’s predecessors and it was important for an emperor to promote an image of familial contentment (even if rumours suggested the contrary). Sabina appeared on the coinage during her lifetime and was styled Augusta. Her association with Concordia on the coin shown in Figure 18 promotes an image of harmony and well-being in the imperial family.

Sabina’s deification also suggests her importance. The relief panel shown in Figure 17 makes clear reference to her place among the gods, depicting her ascent to heaven from the funeral pyre, while foregrounding this deification in terms of her relationship to Hadrian. The emperor points heavenwards, bearing witness to her apotheosis, though notably his gaze, and that of his attendant, is not towards the heavens. Sabina soars upwards; Hadrian remains rooted to the ground. He is the son of a god and the husband of a goddess, but very much the living and human emperor.

The relief panel shown in Figure 17 powerfully suggests Sabina’s importance to the dynasty, but it is still notable that Hadrian is in the foreground and cast on a bigger scale; he, more than Sabina, dominates the panel. However, Penelope Davies has noted that when in its original, probably outdoor, location, with the overhead light source of the sun, the relief of Sabina may have ‘cast the empress into a celestial radiance appropriate for one experiencing apotheosis. Seen in this light, the balance of the scene changes: Hadrian is no longer the main focus, and the two imperial figures bear similar weight’ (Davies, 2000, p. 116). The importance of women in dynastic politics should not be underestimated, even if ultimately their imagery was promoted and manipulated by men.

Activity 11

Read the inscription from Hadrian’s mausoleum in Primary Source 5.

Is there anything that strikes you as unusual about its content?

Discussion

This inscription was set up by Hadrian’s successor, Antoninus Pius, on the completion of Hadrian’s mausoleum. The inscription is full of formal titles and powers that designate the authority of both emperors. But there are several things that you may have noticed about the content. The most striking is that although the mausoleum was commissioned by Hadrian, it is the name of Antoninus Pius which comes first in the inscription. The living emperor takes priority over the dead one. By contrast, Sabina’s name comes last in the inscription and is not associated with a long list of titles, yet she is styled divine. Hadrian is termed the son and grandson of gods, but he is not described as a god; nor is his adopted son and successor (Antoninus Pius) styled son of a god. You may recall from your earlier work that there was some delay in the deification of Hadrian. It seems likely that Antoninus Pius set up this inscription before Hadrian was deified, and thus in the inscription, despite being named last, the dead empress had higher status than the dead emperor.

Both Hadrian, then, and his successors were very aware of the importance of honouring their predecessors and creating a divine aura around the imperial family. Early in his reign Hadrian was already thinking about his own death and dynastic legacy. He began work on his mausoleum in the 120s CE, but at his death in 138 CE it may still have been incomplete. It is a monument with a long history, and was at one time used by the popes as a fort, prison and castle, making what now survives of the original structure often difficult to understand.

Activity 12

Go to the interactive map and click on the markers for the mausoleum of Augustus and the mausoleum of Hadrian.

What are the most striking similarities and differences between the two monuments?

Discussion

The most striking similarities between the two mausolea are their size, shape and location. Both are large-scale monumental structures planned by both emperors years before their deaths. Both mausolea are circular in shape. Both are located near the banks of the Tiber. And both had a major and lasting impact on the topography of Rome. There are differences between the two structures in the details of their execution that you may have identified. For example, the mausoleum of Hadrian sits on a square base, unlike Augustus’ mausoleum; and Hadrian’s mausoleum is integrated with a bridge across the Tiber, whereas Augustus’ mausoleum is integrated with the Augustan redevelopment of the Campus Martius.

Dio Cassius mentions that Hadrian began work on his tomb because the mausoleum of Augustus was full (Dio Cassius 69.23.1). Certainly Augustus’ mausoleum was in use for well over a century. Even if there were pragmatic factors in the decision to build a new imperial tomb, Hadrian was inspired by Augustus, while also wanting to outdo him. Augustus was the first Roman emperor and, someone who was greatly admired for the peace and stability he brought, and for how he rebuilt Rome. Later emperors often looked to Augustus as the emperor they most needed to emulate and surpass.

Activity 13

Turn to Reading 2. This is an extract from Penelope Davies’ book Death and the Emperor (2000).

Why did Hadrian place his mausoleum where he did? And how was it integrated into the topography of Rome?

Discussion

As Davies mentions, some scholars have been surprised at Hadrian’s choice of location for his mausoleum. The Ager Vaticanus was on the edge of town, the wrong side of the Tiber, with few religious or cultural associations and an area which produced wine of inferior quality. However, the emperors owned property here and it provided an unproblematic blank canvas, with the potential for something on a big enough scale to have a real impact. You may not have found Davies’ suggestion, that the Tiber was intended to evoke the River Styx, convincing. Is she overstating Hadrian’s interests in the underworld in this analogy? Did Augustus have similar thoughts when he placed his mausoleum near the Tiber? This aside, it is clear that Hadrian’s choice of site was not haphazard. It would have been highly visible at key traffic points, and having its own bridge increased access to this area. The mausoleum and the Pons Aelius should be seen as integrated. Due consideration was given to how the mausoleum fitted into the pre-Hadrianic and Hadrianic skyline, thereby weaving Hadrian into the cityscape of Rome. Hadrian was looking back to Augustus, but also creating connections with other structures that had a significance to his reign, such as Trajan’s Column and the Pantheon. There were, then, carefully ‘scripted views’ (p. 160) of Hadrian’s mausoleum, constructed to present a narrative of the dynasty and of Hadrian as a god in waiting.

In this section we have explored how Hadrian used death and divinity to promote himself. He exploited the deaths of others and anticipated his own death, all the time weaving a dynastic story around himself. His fascination with divinity may to us seem vain or egotistical. But it also reminds us that Roman traditions and culture, including those centred on religion, can be alien to us. Even if Hadrian was being self-serving and primarily thinking of his own posthumous divine status and reputation, by considering the dynasty he was also serving Rome and promoting stability. Arguably the best legacy an emperor could leave was a good successor, secure in his position, rather than a period of civil war and destruction. Hadrian may not have been the best emperor, but he succeeded in consolidating a dynasty, and thereby protected his monumental legacy too.

This is a black-and-white photograph of a circular medallion seen against a light grey background. It shows a bridge, which has a flat top, approached by a steep slope on either side. The bridge is supported on the piers of seven arches. The three central arches are tall and of the same width and height. The ones either side of them at the top of the slopes are narrower and slightly lower. The arches to the far left and right at the bottom of the slopes are the narrowest and lowest. There is a parapet along both sides of the bridge. On the top of the bridge four tall pillars capped with statues stand on the parapet at the front and back. Another tall pillar with a statue at the base of the slopes can be seen on either side.

A river is shown flowing through the central three arches. A road can be seen going through the second arch on the left.

Conclusion

Hadrian may not have been popular in some quarters and the delay to his deification may reflect this, but we can see in the monuments of Rome that he had a vision for the city. As with any emperor, some of these schemes may well have been grandiose and self-aggrandising, but there were also pragmatic and religious motives. Large-scale building schemes brought employment to Rome, exploited and displayed the riches of empire, and made the city look like the capital of an empire: a place that was wealthy, stable and well governed. If these building schemes were given a religious aura, with buildings often dedicated to the gods, then the emperor was further promoting divine favour for Rome, rather than blatantly advertising his own success. It is notable that, like Augustus before him, Hadrian rarely attached his name to the buildings that he funded or restored.

Through his buildings Hadrian also carefully entwined his present with Rome’s past and future. He looked back to his predecessors – the ultimate prototype, Augustus, and his own adopted father, Trajan – but also provided for the future and continuity of the dynasty through structures such as his mausoleum. In doing so, Hadrian helped to put Rome on a secure footing for his successors. This is not to say that monumentalising Rome was the only thing that a good emperor needed to do. Domitian did it too, and ultimately got little credit for it. But a good emperor did need to think about how his reign was promoted through the visual and architectural environment that would ultimately become a significant part of his legacy; that is, if he achieved the most important thing of all: an emperor of his choosing to succeed him.

Readings

Primary Source 1 SHA, Hadrian

Source: Birley, A. (trans.) (1976) Lives of the Later Caesars, London, Penguin, pp. 57–87.

Hadrian

[p. 57] 1. Hadrian’s family derived originally from Picenum but his more recent ancestors were from Spain – at least, Hadrian himself in his autobiography records that his ancestors were natives of Hadria who had settled at Italica in the time of the Scipios.Footnote 1 Hadrian’s father was Aelius Hadrianus, surnamed Afer, a cousin of the Emperor Trajan. His mother was Domitia Paulina, born at Gades [Cadiz]; his sister was Paulina, who was married to Servianus; and his wife was Sabina.Footnote 2 His great-great-great-grandfather Maryllinus was the first member of the family to be a senator of the Roman people. Hadrian was born on the ninth day before the Kalends of February [24 January] when the consuls were Vespasian for the seventh time and Titus for the second [a.d. 76].

In his tenth year he lost his father and had Ulpius Traianus (Trajan), then of praetorian rank, his cousin and the future emperor, and Acilius Attiantus,Footnote 3 as his guardians. He immersed himself rather enthusiastically in Greek studies – in fact he was so attracted in this direction that some people used to call him a ‘little Greek’. 2. In his fifteenth year he returned to his home [p. 58] town, and at once began military training.Footnote 4 He was keen on hunting, so much so as to arouse criticism, hence he was taken away from Italica by Trajan and treated as his son. Soon after, he was appointed a member for the Board of Ten (decemvir litibus iudicandis),Footnote 5 and this was followed by a commission as tribune in the legion II Adiutrix. After this he was transferred to Lower Moesia – it was, by this time, the very end of Domitian’s principate. In Lower Moesia he is said to have learned that he would be emperor from an astrologer, who told him the same things which, he had found out, had been predicted by his great-uncle Aelius Hadrianus, a man skilled in astrological matters. When Trajan was adopted by Nerva, Hadrian was sent to give the army’s congratulations, and was then transferred to Upper Germany. It was from this province that he was hurrying to Trajan to be the first to announce Nerva’s death, when he was detained for some while by Servianus, his sister’s husband, delayed by the deliberate breaking of his carriage. Servianus incited Trajan against Hadrian by revealing to him what he was spending and the debts he had contracted. But he made his way on foot and arrived before Servianus’ emissary (beneficiarius).Footnote 6 He was in favour with Trajan, and yet he did not fail, making use of the tutors assigned to Trajan’s boy favourites, to …Footnote 7 with the encouragement of Gallus. Indeed, at this time, when he was anxious about the emperor’s opinion of him, he consulted the ‘Virgilian oracle’ and this is what came out:

[p. 59] But what’s the man, who from afar appears,

His head with olive crown’d, his hand a censer bears?

His hoary beard, and holy vestments bring

His lost idea back: I know the Roman king.

He shall to peaceful Rome new laws ordain:

Call’d from his mean abode, a scepter to sustain.Footnote 8

Others said that this oracle came to him from the Sibylline verses. He also had a forecast that he would soon become emperor in the reply emanating from the shrine of Jupiter Niceforius, which Apollonius of Syria, the Platonist, has included in his books.Footnote 9

Finally, when SuraFootnote 10 gave his support, he at once returned into fuller friendship with Trajan, receiving, as his wife, Trajan’s niece (his sister’s daughter) – Plotina being in favour of the match, while Trajan, according to Marius Maximus, was not greatly enthusiastic. 3. He served his quaestorship when the consuls were Trajan for the fourth time and Articuleius [a.d. 101]; during his tenure of office he gave attention to his Latin, and reached the highest proficiency and eloquence after having been laughed at for his somewhat uncultivated accent while reading an address of the emperor in the Senate. After his quaestorship he was curator of the Acts of the Senate, and followed Trajan to the Dacian Wars in a position of fairly close intimacy; at this time, indeed, he states that he indulged in wine too, so as to fall in with Trajan’s habits, and that he was very richly rewarded for this by Trajan. He was made tribune of the plebs when the consuls were Candidus and Quadratus, each for the second time [a.d. 105]; he claims that in this magistracy he was given an omen that he would receive perpetual tribunician power, in that he lost the cloaks which the tribunes of the plebs used to wear in rainy weather, but which the emperors never wear. (For which reason even today [p. 60] emperors appear before the citizens without a cloak.) In the second Dacian expedition Trajan put him in command of the legion I Minervia and took him with him; and at this time, certainly his many outstanding deeds became renowned. Hence, having been presented with a diamond which Trajan had received from Nerva, he was encouraged to hope for the succession. He was made praetor when the consuls were Suburanus and Servianus, each for the second timeFootnote 11, and he received four million sesterces from Trajan to put on games. After this he was sent as a praetorian governor to Lower Pannonia; he restrained the Sarmatians, preserved military discipline, and checked the procurators who were overstepping the mark. For this he was made consul [a.d. 108].

While holding this magistracy, he learned from Sura that he was to be adopted by Trajan, and was then no longer despised and ignored by Trajan’s friends. Indeed, on the death of Sura, Tajan’s intimacy with him increased, the reason being principally the speeches which he composed for the emperor. 4. He enjoyed the favour of Plotina too, and it was through her support that he was appointed to a governorship at the time of the Parthian expedition. At this period, at any rate, Hadrian enjoyed the friendship of Sosius Senecio, Aemilius Papus and Platorius NeposFootnote 12 from the senatorial order, and, from the equestrian order, of Attianus, his former guardian, Livianus [p. 61] and Turbo.Footnote 13 He got a guarantee that he would be adopted when Palma and CelsusFootnote 14 – who were always his enemies and whom he subsequently attacked himself – fell under suspicion of plotting a usurpation. His appointment as consul for the second time [a.d. 118], through the favour of Plotina, served to make his adoption a completely foregone conclusion. Wide-spread rumour asserted that he had bribed Trajan’s freedmen, had cultivated his boy favourites and had had frequent sexual relations with them during the periods when he was an inner member of the court. On the fifth day before the Ides of August [9 August a.d. 117], while governor of Syria, he received his letter of adoption, and he ordered the anniversary of his adoption to be celebrated on that date. On the third day before the Ides of the same month [11 August] the death of Trajan was reported to him; he decreed that the anniversary of his accession should be celebrated on that day.

There was of course a persistent rumour that it had been in Trajan’s mind to leave Neratius PriscusFootnote 15 and not Hadrian as his successor, with the concurrence of many of his friends, to the extent that he once said to Priscus: ‘I commend the provinces to you if anything should befall me.’ Many indeed say that Trajan had it in mind to die without a definite successor, following the example of Alexander the Macedonian; and many say that he wanted to send an address to the Senate, to request that if anything should befall him the Senate should give a princeps to the Roman republic, adding some names from which it should choose the best man. There are not lacking those who have recorded that it was through Plotina’s [p. 62] party, Trajan being already dead, that Hadrian was received into adoption; and that a substitute impersonating Trajan spoke the words, in a tired voice.

5. When he gained the imperial power he at once set himself to follow ancestral custom, and gave his attention to maintaining peace throughout the world. For those nations which Trajan had subjugated were defecting, the Moors were aroused, the Sarmatians were making war, the Britons could not be kept under Roman control, Egypt was being pressed by insurrection, and, finally, Libya and Palestine were exhibiting the spirit of rebellion.Footnote 16 He therefore gave up everything beyond the Euphrates and Tigris, following the example of Cato, as he said, who declared the Macedonians to be free because they could not be protected.Footnote 17 Parthamasiris,Footnote 18 whom Trajan had made king of the Parthians, he appointed a king over the neighbouring peoples, because he saw that he did not carry great weight among the Parthians.

So great in fact was his immediate desire to show clemency that, when in his first days as emperor he was warned by Attianus, in a letter, that Baebius MacerFootnote 19 the prefect of the city should be murdered in case he opposed his rule, also Laberius Maximus, who was in exile on an island, and Frugi Crassus,Footnote 20 he harmed none of them; although subsequently, without an order from Hadrian, a procurator killed Crassus when he left the island, on the grounds that he was planning a coup. He gave a double donative to the soldiers, to mark the opening of his reign. He disarmed Lusius Quietus,Footnote 21 taking away from him the [p. 63] Moorish tribesmen whom he had under his command, because he had come under suspicion of aiming for the imperial power, and Marcius Turbo was appointed when the Jews had been suppressed, to put down the rising in Mauretania.Footnote 22 After this he left Antioch to inspect the remains of Trajan, which were being escorted by Attianus, Plotina, and Matidia, and, placing Catilius SeverusFootnote 23 in command of Syria, he came to Rome by way of Illyricum. 6. In a letter sent to the Senate – and it was certainly very carefully composed – he requested divine honours for Trajan; and for this he obtained unanimous support; in fact, the Senate spontaneously decreed many things in honour of Trajan which Hadrian had not requested. When he wrote to the Senate he asked for pardon because he had not given the Senate the right of deciding about his accession to the imperial power, explaining that he had been hailed as emperor by the soldiers in precipitate fashion because the republic could not be without an emperor. When the Senate offered to him the triumph which belonged of right to Trajan, he refused it for himself, and conveyed the effigy of Trajan in the triumphal chariot, so that the best of emperors, even after his death, might not lose the honour of a triumph. He deferred the acceptance of the title of Father of the Fatherland, which was offered him straightaway, and again later, because Augustus had earned this title at a late stage.Footnote 24 He remitted Italy’s crown-gold and reduced it for the provinces, while he did indeed make a statement, courting popularity and carefully worded, about the problems of the public treasury.

Then, hearing of the uprising of the Sarmatians and Roxalani, he made for Moesia, sending the armies ahead.Footnote 25 He placed [p. 64] Marcius Turbo in command of Pannonia and Dacia for the time being, conferring the insignia of the prefecture on him after his post in Mauretania. With the king of the Roxolani, who was complaining about the reduction of his subsidy, he made peace, after the matter had been examined.