3.3.4 Market timing: can you outperform the market?

The other way to try to outperform an index is to try to forecast the movement of the market by adjusting the beta of the portfolio. This can involve increasing the amount of shares in the portfolio when the market is expected to rise, and reverting to cash just before the market goes down. By varying beta, fund managers are trying to time their entry into the market, and their exit out of the market. They are indulging in market timing.

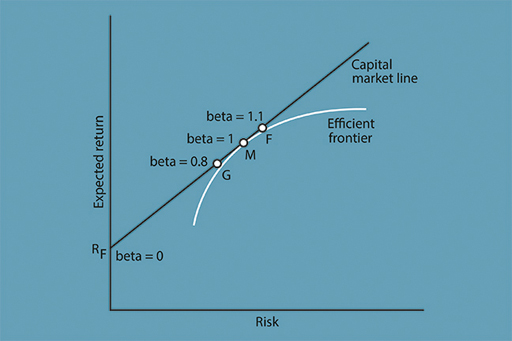

In fact, there are two ways in which active fund managers can attempt to time the market. The first is by varying the amount of leverage in a passive portfolio, moving up and down the capital market line and varying the beta of the portfolio according to whether they think the market will rise or fall. The second way is to alter the composition of the portfolio by increasing the proportion of shares that have high beta when the market is expected to rise, and increasing the proportion of low-beta shares when the market is expected to go down.

The investor can choose between different types of shares. An example of a cyclical, or aggressive, share is an airline – which does particularly well in a boom and particularly badly in a recession – giving it a beta of more than 1 (high beta). An example of a non-cyclical (defensive) share is a utility or food manufacturer – people use electricity, eat food and drink water regardless of the state of the economy – and these typically have a beta of less than 1 (low beta). Typically, low-beta shares do relatively well in a recession, and high-beta shares do relatively well in boom times. So shares can have high or low betas as well as portfolios, but, if the active fund manager buys a portfolio of shares selected for their high or low betas and not the market portfolio, M, they will no longer have a fully efficient portfolio, and will bear specific as well as systematic risk.

So, whether adopting a stock selection strategy or a market timing strategy, the active fund manager is taking on more risk than the passive fund manager, by varying share beta risk (market timing) and/or through taking on specific risk (stock selection). Active fund managers also reduce the net expected return by charging higher fees than do passive fund managers; the latter run index funds in a competitive market and charge low fees for the replication of indices (essentially because less work is required to seek information about future price changes). Proponents of the CAPM, which assumes no particular investment skill, believe that the active approach is doomed to failure. Active managers argue that since some of them make a good living, some of them must be successful some of the time.

There is little evidence of market timing skills. A few people have become famous for timing the market correctly – George Soros for selling sterling before sterling left the Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992, and Jon Moulton of Alchemy Partners for selling securities linked to sub-prime mortgages before that market collapsed, but these are individual occurrences for two particular investors and do not reflect general market timing ability. Indeed, retail investors are often sellers in a bear market when prices have already fallen and buyers in a bull market, the exact opposite of ‘buying low and selling high’, which is effectively what a market timing strategy attempts to do.

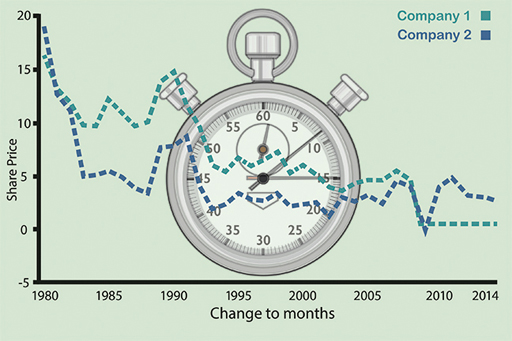

A way to reduce mistakes of market timing is to invest on a regular basis, such as monthly, quarterly or yearly. This is called pound cost averaging, and reduces the risk of buying at the high and selling at the low. It also reduces the chance of getting market timing right – buying at the low and selling at the high. If someone invested, for example, £50 a month in a unit trust that invested in shares, then if the market fell they would buy more units and if the market rose they would buy fewer units, since they would be spending an equal amount each month on units that varied in price over time. It is also worth adopting a similar approach for selling. If someone wants to sell, it makes sense to sell holdings in regular amounts, since it is difficult to tell when the market has reached a peak. Using this technique may be preferable in order to receive a reasonable average return, rather than to hold on, possibly miss the height of the boom, and have to sell when prices have already fallen.