Music and its media

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 7 May 2024, 5:16 PM

Music and its media

Introduction

This free course will provide an introduction to some of the main ways in which music is transmitted. There are three case studies, each of which focuses on one form of musical media during a specific historical period in a particular geographical location. You will begin by looking at a copyist of music manuscripts in the sixteenth-century Low Countries; you will then study a music publisher in early eighteenth-century London; and you will conclude by looking at a record label in twentieth-century America. In doing so you will consider how the different appearances and contents of musical media are also a reflection of their social context, the purpose they serve and what they signify to their recipients.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course A342 Central questions in the study of music.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

demonstrate knowledge of the main ways in which music is transmitted

understand how the means of communicating a particular piece can change over time

examine examples of musical media from different historical periods and geographical locations

show how the appearance and contents of a musical source can reflect its musical and non-musical context, its creator(s) and user(s).

1 How is music transmitted?

Before you begin to work through each of the case studies, you should first consider some of the main ways music is transmitted, and the issues you should bear in mind when examining instances of these. Below is a brief chronology of the main developments in the transmission of western music.

- Oral/aural transmission. To begin with, pieces of music could only be passed orally from one person to the next. While this oral or aural transmission of music allowed recipients to experience first-hand how a piece might be performed, the scope of communication was limited to this contact between individuals.

- Manuscripts. In certain contexts, oral/aural transmission was not felt to be sufficient; there was a need to have a more permanent and visible record of musical works and practices. This led to the representation of musical sound through forms of notation – the origins of current western notation can be traced back to plainchant manuscripts of the ninth century. Through this written communication, musical pieces and practices could disseminate further. In these early years, this visual representation of music was purely in manuscript, and these handwritten documents were copied only for the small section of society that was musically literate.

- Printing and publishing. The invention of the printing press in the mid-fifteenth century, and the gradual development of music publishing, allowed for the dissemination of pieces to a wider audience.

- Recording. Finally, the invention of the phonograph in 1877 introduced the possibility of recording musical sounds without the need for visual representation on the page. It allowed the transmission to a wide audience of music that was not notated, such as certain kinds of folk and popular music in the western and non-western worlds.

This chronological outline should not give the impression that each form of musical media was supplanted by the next – all of the above forms of communication are still in use today. In the UK, we can transmit and experience musical works orally/aurally, through forms of notation (handwritten or printed) or through recordings. Nor is the above chronology necessarily an indication of increasing sophistication in the communication of music. Different cultures and different musical genres have adopted one or more of these forms of media as a reflection of their social and musical circumstances. Whereas in western art music, for example, a piece might be communicated through various means (a composer’s manuscript draft of a piece might be transmitted further in a printed edition, which is then performed and recorded), some musical genres, such as pop music, have focused on recording technology rather than notation for the creation and dissemination of works. Other traditions, including many in the non-western world, have passed on musical practices and works largely through oral/aural communication.

In spite of the technological developments listed above, the one form of communication which remains inherent to all our musical experiences is the oral/aural transmission of pieces and practices. We have all experienced this way of communicating and learning music, without reference to notation. Consider, for example, the playground songs you shared as a child, or well-known football chants or Christmas carols. Furthermore, even when a piece has been notated, there are always unwritten performance practices that can only be learned orally/aurally from another musician. Notation has limitations in communicating performing conventions, and is typically just a starting point for the performer – other features can be learned only by listening to a performance, from subtleties such as dynamics, timbre and rubato, to more substantial changes, such as the addition of ornamentation or sections of improvised material. This is why the use of recording technology is so significant for the transmission of music: it not only allows composers to create and communicate unique pieces of music without the need for notation, it also provides a means of documenting orally transmitted pieces and practices that we might find difficult to represent on the page (Taruskin, 2005, p. 481; Boorman, 1999).

1.1 Different musical media

In the next section, you will begin your study of three distinct snapshots in the overall development of musical media. You will not examine the purely oral/aural transmission of repertory extensively in this course; instead, you will focus on the three forms of musical media that, by removing the need for face-to-face contact for the transmission of works, today allow us to study music of the past: manuscripts, prints and recordings. As you work through these case studies, you should bear in mind that each musical source (whether manuscript, print or recording) represents merely one instance of the transmission of a piece; the repertory it contains has most probably been circulated in various ways and vested with different functions and meanings over the years.

Activity 1

Before you move on to the three case studies, let’s consider the previous paragraph by looking at the song ‘Happy Birthday to You’. Can you remember how you learned this song? What do you think are the function and meaning of the song (i.e. when is it normally performed)?

Discussion

I cannot remember exactly how or where I learned this song, but I am sure that I picked it up from other people. The song is of course customarily performed at birthday celebrations – it brings a group of friends or relatives together in sending birthday wishes to a loved one.

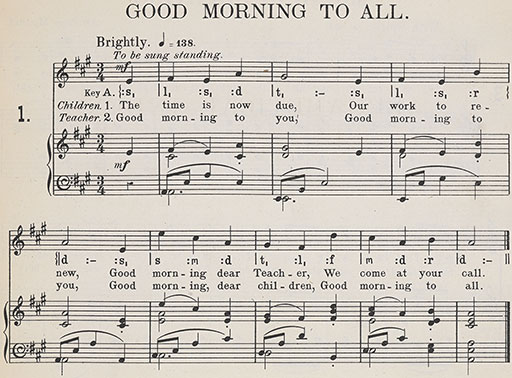

Although this is the common understanding of the song today – one we have learned from others for a birthday celebration – the piece was actually originally communicated through different means, and for a different purpose. Figure 1 presents the song as it appeared in the anthology Song Stories for the Kindergarten (first published in Chicago in 1893), with music by Mildred J. Hill and words by Patty S. Hill. The title of this anthology clearly conveys its purpose: educational songs for groups of very young children – an intention reflected in the simplicity of the music and lyrics. The original performances of this melody were therefore in a more controlled environment; as indicated in the score in Figure 1, it was to be sung by children and their teacher at the start of the day while standing. Only in the 1930s were the now familiar lyrics, ‘Happy birthday to you’, applied to the song.

This is a score of a song in the anthology Song Stories for the Kindergarten, for voice (in the treble clef) and piano (in the treble and bass clef). At the top of the page, in capitals, is the title of the song ‘Good morning to all.’ The song is in 3/4 time and the key signature has three sharps, indicating A major. Above the first bar is the performance direction ‘Brightly’ with the tempo indication of a crotchet beat at 138, the instruction ‘to be sung standing’ and the dynamic marking ‘mf’. Beneath the notes in the top line (for voice), are two lines of text. The first, preceded by the indication ‘Children’, is: ‘The time is now due, Our work to renew, Good morning dear Teacher, We come at your call’. The second line, for the Teacher, is: ‘Good morning to you, Good morning to you, Good morning dear children, Good morning to all.’

The change in the way this song has been circulated demonstrates not only its popularity, but also how the meaning, function and means of transmitting a piece can alter over time. The following case studies focus on three examples of musical media – manuscript, print and recording – to show what a specific musical source, and other materials related to its production, can tell us about its historical and social context, and what each source accomplished and meant at the time of its creation. As you work through the case studies, consider the relationship between the form of each musical source and its recipient(s) – how do their appearance and content reflect the people for whom they were created?

2 Music manuscripts of the sixteenth-century Low Countries

Before the invention of the printing press, the only tangible means by which musical works could be preserved and transmitted was through manuscripts produced for a very limited audience. Very few people owned books before 1700; these largely belonged to affluent patrons or collectors, institutions or scholars. Unlike the mass-produced prints of later years, aimed at the broader public, manuscripts often reflect a unique situation – one owner or function – that influenced their form of production, format and repertory. Yet there is also evidence of the creation of multiple manuscript copies of a piece, some being sold in the same way as music prints (Boorman et al., 2014a). Even after music printing had been firmly established, repertory continued to circulate in manuscript. This was perhaps due to there being a lack of music printer-publishers in certain locations, the wish to deliberately restrict or retain control over the dissemination of repertory, or to assert the status of a specially prepared copy (Wyn Jones, 2005, p. 140). Despite this parallel existence of manuscript and print, in general, as the new technology took over, the use of manuscripts as a form of musical media declined – in later years the manuscript became more closely associated with composers’ workings or repertories for a limited market.

The manuscripts that have been passed down to us today can generally be categorised as: presentation copies, often heavily decorated; autographs showing composers’ workings; copies for use by performers; or copies compiled for reference or study (Boorman et al., 2014a). In this case study, we will look at a workshop in the Low Countries in the early sixteenth century, when manuscript transmission was still very common, to see what the format and content of the manuscripts produced there can reveal about the intended users of the texts.

2.1 The music manuscripts of the Alamire workshop

You are now going to study one of the most significant music copyists of the early sixteenth century – Pierre (or Petrus) Alamire (c.1470–1536). Alamire served the courts of Margaret of Austria, Regent of the Habsburg Netherlands from 1506 to 1530 (see Figure 2); her nephew Charles (the future Holy Roman Emperor); and Margaret’s successor as regent, Mary, Queen of Hungary (Kellman, 2014). Margaret’s territory in the Netherlands had been ruled by her brother Philip; she became regent there following his death in 1506, acting as guardian for her aforementioned nephew, Charles, until he attained his majority (Blockmans, 1999, pp. 8–9).

This is a portrait of Margaret of Austria. Only Margaret’s face and upper body can be seen. She is depicted turned and looking slightly to the left. She wears a black dress, the outline of which is difficult to see against the dark background of the picture. She also wears a widow’s hood - her hair is completely covered by a white cap with a veil over her forehead, and her throat is also covered by a large square collar. Her bare hands rest on a brown table top that can just be seen at the bottom of the picture.

The Netherlands had come under Habsburg control through the marriage in 1477 of Margaret’s father Maximilian I (King of the Romans and then Holy Roman Emperor, 1486–1519) to Mary, daughter of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. The Duchy of Burgundy had comprised parts of modern-day France and the Netherlands, and during the fifteenth century the court of the Burgundian dukes had emerged as a centre of cultural splendour and musical patronage, emulated across Europe. On her appointment as Regent of the Netherlands, Margaret of Austria chose Mechelen (French: Malines) as her residence and began to reestablish the cultural and musical patronage of the Burgundian court, as is reflected in the music manuscripts that survive from her regency (Picker, 1965, pp. 11–12, 21, 27–9).

Pierre Alamire had moved to Mechelen from Antwerp by 1516 and was one of several copyists of polyphonic music serving the Netherlands courts during the early sixteenth century. Around forty-seven choirbooks and partbooks, as well as some fourteen manuscript fragments, that were partly or wholly copied, or supervised, by Alamire have survived from this period. Among those produced in this way were beautifully illustrated manuscripts for the chapels of Margaret, Charles, Maximilian and Mary of Hungary. Others were presented as gifts to significant music patrons, such as King Henry VIII of England, Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony and Pope Leo X. While in the service of the Habsburgs, Alamire continued to accept other independent commissions, such as for the nearby confraternities of Our Lady in Antwerp and ’s-Hertogenbosch as well as for other significant individuals (Kellman, 2014). You will now look at two of the manuscripts produced in Alamire’s workshop to see if their appearances and contents can reveal anything about their patron, their recipient or their intended use.

2.2 Two manuscripts from the Alamire workshop

The first manuscript (Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale Ms. 228) is a large chansonnier (i.e. a volume containing primarily settings of French lyric poetry – chansons) created between 1516 and 1523 and comprising seventy-three parchment leaves of the dimensions 36.5 × 26 cm. In addition to thirty-nine chansons, the book presents one Flemish song, seven Latin sacred songs (‘motets’), seven songs connecting French and Latin texts, and three secular Latin works, all set for three or more voices (Picker, 1999, pp. 69–70).

The second manuscript (Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Handschriftensammlung, Ms. 9814) is estimated to date from 1519–25 and was later owned by Raimund Fugger the Elder (1489–1535), a wealthy merchant of Augsburg, Germany. It consists of twenty-one individual paper folios of the dimensions 29–29.9 × 20.2–21.7 cm, each presenting a voice part.

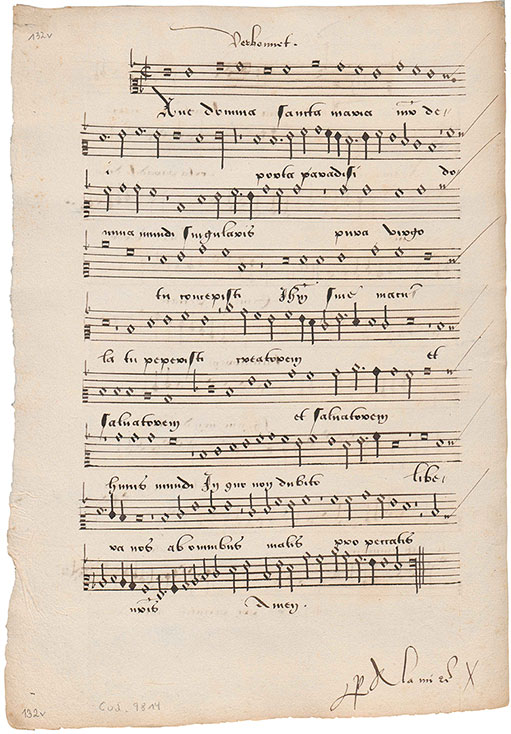

Through close study of the script and format of these manuscripts it has been possible to establish that the second of these manuscripts was copied by Alamire himself (notice his signature on the bottom right-hand corner of a page of the manuscript shown in Figure 4) while the first was by another scribe of Alamire’s circle at the Netherlands court (Kellman, 1999, p. 146).

Activity 2

To begin with, listen to Track 1 to gain a sense of the kind of music contained in the manuscripts. This track is an extract from the first piece presented in Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale Ms. 228, Ave sanctissima Maria, an anonymous motet for six voices, suggested to be by the composer Pierre de la Rue (c.1452–1518) (you will learn more about La Rue’s work later on). You can see the tenor and bass parts of the piece, as presented in the manuscript, in Figure 3.

Activity 3

Now compare the images in Figures 3 and 4 of pages selected from each manuscript. How do these differ in their appearances? Are they decorated or do they just present the music? What might their appearances reveal about the status of their owners? Do they look valuable or are they of a simpler format and perhaps more functional?

This shows a page from the Brussels Manuscript 228. The top half of the page shows the six staves of the tenor part of ‘Ave sanctissima Maria’ and the bottom half shows the three staves of the bass part, in black sixteenth-century notation. The music is surrounded by an illuminated border, with diagonal broad stripes of green, silver and gold decorated with pictures of jewels and flowers. In the top left-hand corner, before the start of the tenor part, is a square miniature showing Margaret of Austria kneeling in prayer. She is dressed in gold and ermine and wears a widow’s hood. The words ‘Memento mei’ can be seen by her mouth. Lower down the page, before the start of the bass part, is another square miniature, showing a coat of arms against a grey background with a daisy in each corner.

This shows a page from Ms. 9814 in the Austrian National Library, Vienna. Unlike the previous manuscript, the page shows only the music, with no borders, miniatures or other decorations. Handwritten black notation of the sixteenth century is presented on white paper. Above the music is the word ‘Verbonnet’ and in the bottom right-hand corner is the signature ‘Alamire’.

Discussion

The first manuscript is beautifully decorated with colourful miniatures, an intricate border and clear notation, whereas the second has a simpler format, although the stave is still very clear. To me, their appearances indicate that the first is perhaps more valuable and owned by somebody of high status, whereas the second, being less ornate, is probably not as prestigious.

While the simple appearance of the second manuscript provides little information about its intended owner, the illustrations in the first manuscript reveal far more about its history. In the top left corner of folio 2r we see a portrait of Margaret of Austria, sumptuously dressed in gold and ermine but still wearing a widow’s hood (her second husband had died in 1504). Margaret is painted here in a devout pose, saying the prayer ‘Memento mei’ (‘Remember me’). Beneath this, her coat of arms can be seen surrounded by daisies, which together with pearls – both ‘marguerites’ in Old French – feature throughout the beautifully decorated borders of the manuscript (Picker, 1965, p. 2). These illustrations therefore indicate that the manuscript has strong links with Margaret’s court. You will now look at the contents of the manuscript to see if these can provide any more information about its origins.

2.3 The contents of the Brussels manuscript

Only one of the pieces in this manuscript bears the name of a composer – Josquin des Prez (c.1450/55–1521) – yet the composers of many of the anonymous pieces have been identified from other sources. Along with Josquin, musicians of the French court represented here include Loyset Compère (c.1445–1518), Jean de Ockeghem (c.1410–1497) and Antoine Brumel (c.1460–c.1512/13). There are also a number of works by musicians employed at the Burgundian chapel during Margaret’s lifetime, under the patronage of her brother Philip: Alexander Agricola (c.1445/46–1506), Gaspar van Weerbeke (c.1445– after 1516) and, most prominently, Pierre de la Rue (who served the chapel before and during Margaret’s regency). The manuscript’s contents therefore reflect a connection with European court society of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries.

A number of the poems set to music in the manuscript were written by Margaret herself – one of the texts presumed to be by her is a lament for her brother Philip, Se je souspire. This has a tenor line in Latin that includes the words ‘Doleo super te frater mi Philippe’ (‘I grieve for thee, my brother Philippe’). Elsewhere in the manuscript, the motet Proch dolor – in black notation as a sign of mourning – laments the death of Margaret’s father, Emperor Maximilian I, in 1519 (Picker, 1999, pp. 69–70). Further pieces in the manuscript reflect Margaret’s sentiments and the misfortunes she suffered during her lifetime. Two poems by the French court poet Octavien de Saint Gelais (1468–1502) (Tous les regretz and Tous nobles cuers), set here by La Rue, were written to console the young Margaret following her dismissal from the French court in 1493 – she had been resident there since 1483 during her betrothal to Charles VIII of France, but he renounced the engagement and instead married Anne, Duchess of Brittany. The theme of regret reappears throughout the manuscript, which also includes two settings of Dido’s lament from Virgil’s Aeneid, both again by composers of the Netherlands court – Marbrianus de Orto (c.1460–1529) and Agricola. Margaret’s court poet, Jean Lemaire de Belges (c.1473–1514), is also represented, providing texts for two of the manuscript’s pieces: the song Plus nulz regretz, written to celebrate a treaty between the Habsburg empire and England in 1508, and a setting of the final verse (‘Soubz ce tumbel’) of Lemaire’s Epitaphe de l’Amant Vert, which conveys the dying farewell of Margaret’s pet parrot (Picker, 1999, pp. 69–70; 1965, p. 16).

The theory that this lavish manuscript was prepared for Margaret is confirmed by its inclusion in a 1523 inventory of her library (although not in an earlier catalogue of 1516). Its decorated and undamaged appearance reflects its limited use by a recipient of great stature. It is not only a musical and literary record of the cultural life of Margaret’s court but also a reflection of her personal experiences (Picker, 1999, pp. 69–70).

2.4 The contents of the Vienna manuscript

You are now going to turn to the second manuscript in this case study to see if its contents can likewise provide insights into its origins and use. The format and appearance of the manuscript make this an ostensibly difficult task, although its simple form indicates that it had a very different purpose from the last manuscript you examined. At first glance it is not entirely clear whether these sheets were performing parts or models for other choirbooks or partbooks created in Alamire’s circle. A closer look at the manuscript gives a better indication of its possible use – the sheets are quite large (almost the size of a small choirbook and larger than the biggest partbook in Alamire’s output), and their music and text are very clear. This would suggest that the manuscript was probably intended for performance (Kellman, 1999, p. 146), but by whom?

Of the songs presented in this manuscript, one is anonymous while a number are by composers of the French court (Johannes Ghiselin, fl.1491–1507, Jean Mouton, before 1459–1522, Jean Richafort, c.1480–c.1550) and the Netherlands court (Agricola and La Rue). One work in particular provides insights into the manuscript’s origins. This is the anonymous chanson Plus outré pretens parvenir, which cites Charles V’s imperial motto ‘Plus oultre’ (‘Even further’), reflecting his wish to surpass himself during his reign. The second verse of the song also quotes the motto of Philip the Fair (‘Qui vouldra’ – ‘He who wills’) as well as a phrase from one of Margaret of Austria’s poems in Brussels Ms. 228 – ‘Pour ung jamais’.

Activity 4

Examine the information presented above about the contents of this manuscript. To what extent can the manuscript’s owner be determined from this information? Can this be easily assigned to an individual patron, like the previous manuscript you studied? Or is this not as clear? Don’t worry if you come up with several possible answers to these questions!

Discussion

From the information presented here, I think it is more difficult to link this manuscript with just one person. Like the Brussels source, this manuscript also presents the prestigious repertory of the French and Netherlands courts, which therefore implies that the manuscript was created for an equally illustrious institution. But, unlike the previous manuscript, this collection does not seem to be dominated by one person – Charles V, his father Philip and his aunt and guardian Margaret are all represented in the chanson Plus outré pretens parvenir. The inclusion of this song does, however, indicate the manuscript’s strong connections with the Habsburg dynasty. Along with Alamire’s role in the creation of the manuscript, the chanson presents the possibility that the Vienna manuscript was also produced for use at the Netherlands court.

Kellman has suggested that the chanson Plus outré pretens parvenir might have been composed, and its music copied, for performance at the Netherlands court soon after the election of Charles as emperor in 1519. He claims that the text of this song reflects Charles’s promise to govern well as emperor: ‘in wisdom I want to help anyone who so desires, in peace and war … I have undertaken to maintain my moderation in all things that may come’ (Kellman, 1999, p. 146). Kellman further proposes that the pages formed part of Alamire’s collection of performing parts, which had been used by the chapel of Charles V or Margaret of Austria and for which Alamire no longer had a use – the folios were therefore sent by the scribe to the Fugger family in Augsburg (Kellman, 1999, p. 146).

The two manuscripts, Brussels Ms. 228 and Vienna Ms. 9814, therefore share a connection with the court of Margaret of Austria, not only in their creation by Alamire or his associates, but also in their intended use at the Netherlands court. While they have common traits in their references to members of the Habsburg dynasties and in their repertory being partly by members of the Netherlands court chapel, the great contrast in their appearances alerts us to their different functions and recipients. One is an exquisitely beautiful manuscript compiled for Margaret herself, the other a simpler and functional text possibly created for the use of musicians of the Netherlands court.

3 Music publications of eighteenth-century London

We are now going to turn to a later historical period to examine the printing and publishing of music, which generally allowed for the wider and easier dissemination of pieces. As I mentioned earlier, publication did not necessarily mean that a work was printed – there are examples of repertory circulating in manuscript into the nineteenth century. Conversely, the fact that a work was printed did not indicate that it was published – some prints were produced as luxurious keepsakes while others were restricted in their circulation to maintain a degree of control over performances (Boorman et al., 2014b). In this section, you will examine the wider publication of music in print by focusing on the output of one particular printer-publisher.

From the appearance of the first printed music publications in the late fifteenth century, particular European cities emerged as centres for the production of music prints: Venice, Nuremberg, Paris and Antwerp in the sixteenth century; London from around 1700; Paris between c.1740 and 1760; Vienna from c.1780 and Leipzig from around 1800. From the beginning of the eighteenth century, the quality and quantity of music publications became markedly greater, aided by technological developments in printing, competition between publishers and an increase in the public’s interest in music (Boorman et al. 2014b). In this case study you are going to focus on one of these centres of music publishing – London in the early eighteenth century – and the work of a single music printer-publisher there, John Walsh (c.1665/66–1736). In the same way that you have just looked at the recipients of the manuscripts of Pierre Alamire, here you will consider how the appearance and content of Walsh’s publications (and related documents) reflect the tastes of his London music market c.1700.

3.1 John Walsh and the London audience

Walsh began publishing music in London in 1695, at a time when there were few rivals to his work in this area. His prolific predecessor, the music publisher John Playford (1623–c.1686/87), had left behind a market for music publications which he had nurtured and dominated from the middle of the seventeenth century. Walsh published repertory on an unprecedented scale for London, including works by both English and continental composers. Until around 1730, he worked in partnership first with the publisher and violin maker John Hare (d.1725) and later also with Hare’s son Joseph (d.1733). Walsh was an extremely astute businessman and his output covered a wide range of secular repertory that would appeal to the London audience, including songs, operas, instrumental music and instruction books. He eventually became the principal publisher of Handel’s music. His son, also named John, continued the family business for another thirty years after his father’s death (Kidson et al., 2014).

The success of Walsh’s music publishing business was due to the generally favourable circumstances for music-making in London during the early eighteenth century. Of all the major music centres of the period, it was London where the first regular public concerts took place in 1672, and this environment not only attracted the best professional musicians of the period to the British capital, it also allowed amateur music-making to develop, at home and in music societies. Walsh’s publications were therefore aimed at the section of the London population who would participate in musical performances. In the early years of the eighteenth century, the music-buying public was mainly the wealthier, privileged classes who could afford to attend concerts and go to the opera, and who were willing and able to purchase editions of their favourite music. Later in the eighteenth century, the market began to expand as repertory became more accessible to the middle classes (Edwards, 1976, pp. 57, 59, 83).

Walsh’s publications clearly reflect the wishes of his affluent customers. Besides the popularity of music composed in and for London (such as by Henry Purcell, 1659–1695, and later Handel), musical tastes of the time were dominated by the aristocratic love of Italian culture – many had visited cities such as Venice and Rome on their ‘Grand Tours’ of Europe, and returned to London with great enthusiasm for the music and musicians they had heard in Italy. This taste for Italian music was further demonstrated by the many Italian musicians – singers and instrumentalists – who were welcomed to the British capital. It was this demand for Italian music, together with a love of novelty – the London concert-going public were keen to witness anything ‘new’ or ‘different’ – and the fondness for amateur music-making, that Walsh tried to reflect in his publications.

3.2 Examining Walsh’s publications

You are now going to consider a selection of Walsh’s publications to see how he attempted to cater for his London audience.

Activity 5

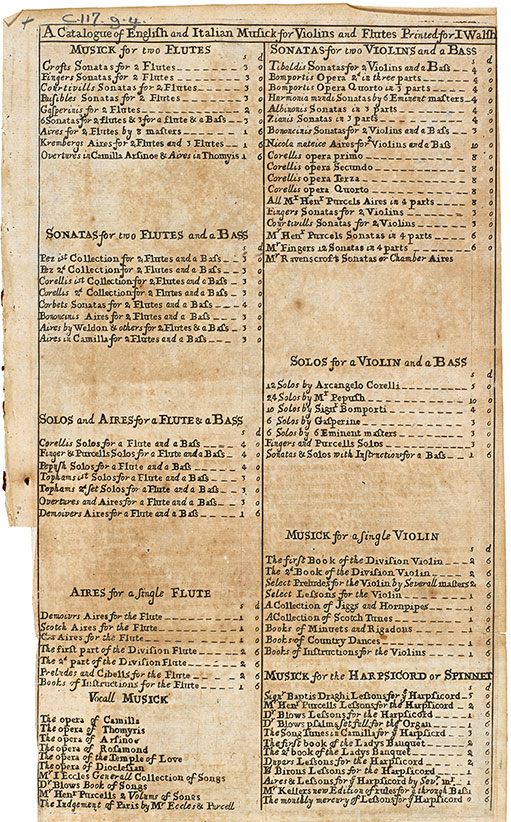

Look at the catalogue of music publications produced by Walsh in around 1710 (Figure 5). How do you think he was trying to appeal to potential customers? See if you can relate the contents of this catalogue to the factors presented in the previous section about the music that was popular with London society at that time.

This is a reproduction of a page from a catalogue of music. It contains a list of works, organised by category and presented in two columns. A price in shillings and pence follows each work, with the exception of those under the heading ‘Vocall Musick’; shillings are designated by the lower-case letter ‘s’ and pence by the lower-case letter ‘d’. The list makes liberal use of italic and superscript formatting, as well as extensive, but not always consistent, capitalisation. Misspellings or variations in spelling are common, and in some cases composers’ names are spelled in different ways on different parts of the page.

The left-hand column reads as follows:

MUSICK for two FLUTES

Crofts Sonatas for 2 Flutes 3s 0d

Fingers Sonatas for 2 Flutes 3s 0d

Courtivills Sonatas for 2 Flutes 3s 0d

Paisibles Sonatas for 2 Flutes 3s 0d

Gasperinis for 2 Flutes 2s 0d

6 Sonatas for 2 flutes & 3 for a flute & a Bass 3s 0d

Aires for 2 Flutes by 8 masters 1s 6d

Krembergs Aires for 2 Flutes and 3 Flutes 1s 6d

Overtures in Camilla Arsinoe & Aires in Thomyis 1s 6d

SONATAS for two FLUTES and a BASS

Pez 1st Collection for 2 Flutes and a Bass 3s 0d

Pez 2d Collection for 2 Flutes and a Bass 3s 0d

Corellis 1st Collection for 2 Flutes and a Bass 3s 0d

Corellis 2d Collection for 2 Flutes and a Bass 3s 0d

Corbets Sonatas for 2 Flutes and a Bass 4s 0d

Bononcinis Aires for 2 Flutes and a Bass 3s 0d

Aires by Weldon & others for 2 Flutes & a Bass 3s 0d

Aires in Camilla for 2 Flutes and a Bass 3s 0d

SOLOS and AIRES for a FLUTE & a BASS

Corellis Solos for a Flute and a Bass 4s 0d

Finger & Purcells Solos for a Flute and a Bass 4s 0d

Pepush Solos for a Flute and a Bass 4s 0d

Tophams 1st Solos for a Flute and a Bass 3s 0d

Tophams 2d Set Solos for a Flute and a Bass 3s 0d

Overtures and Aires for a Flute and a Bass 3s 0d

Demoivers Aires for a Flute and a Bass 1s 6d

AIRES for a single FLUTE

Demoivrs Aires for the Flute 1s 0d

Scotch Aires for the Flute 1s 0d

Cox Aires for the Flute 1s 0d

The first part of the Division Flute 2s 6d

The 2d part of the Division Flute 2s 6d

Preludes and Cibells for the Flute 2s 6d

Books of Instructions for the Flute 1s 6d

Vocall MUSICK

The opera of Camilla

The opera of Thomyris

The opera of Arsinoe

The opera of Rosamond

The opera of the Temple of Love

The opera of Dioclesian

Mr J Eccles Generall Collection of Songs

Dr Blows Book of Songs

Mr Henr Purcells 2 Volums of Songs

The Judgement of Paris by Mr Eccles & Purcell

The right-hand column reads as follows:

SONATAS for two VIOLINS and a BASS

Tibaldis Sonatas for 2 Violins and a Bass 4s 0d

Bomportis Opera 2d in three parts 4s 0d

Bomportis Opera Quorto in 3 parts 4s 0d

Harmonia mundi Sonatas by 6 Eminent masters 4s 0d

Albinonis Sonatas in 3 parts 4s 0d

Zianis Sonatas in 3 parts 4s 0d

Bononcinis Sonatas for 2 Violins and a Bass 3s 0d

Nicola mateice Aires for 2 Violins and a Bass 10s 0d

Corellis opera primo 8s 0d

Corellis opera Secundo 8s 0d

Corellis opera Terza 8s 0d

Corellis opera Quorto 8s 0d

All Mr Henr Purcels Aires in 4 parts 8s 0d

Fingers Sonatas for 2 Violins 3s 0d

Courtivills Sonatas for 2 Violins 3s 0d

Mr Henr Purcels Sonatas in 4 parts 6s 0d

Mr Fingers 12 Sonatas in 4 parts 6s 0d

Mr Ravenscrofts Sonatas or Chamber Aires

SOLOS for a VIOLIN and a BASS

12 Solos by Arcangelo Corelli 5s 0d

24 Solos by Mr Pepush 10s 0d

10 Solos by Signr Bomporti 4s 0d

6 Solos by Gasperine 3s 0d

6 Solos by 6 Eminent masters 3s 0d

Fingers and Purcells Solos 3s 0d

Sonatas & Solos with Instructions for a Bass 1s 6d

MUSICK for a single VIOLIN

The first Book of the Division Violin 2s 6d

The 2d Book of the Division Violin 2s 6d

Select Preludes for the Violin by Severall masters 2s 6d

Select Lessons for the Violin 1s 6d

A Collection of Jiggs and Hornpipes 1s 6d

A Collection of Scotch Tunes 1s 0d

Books of Minuets and Rigadons 1s 6d

Books of Country Dances 1s 6d

Books of Instructions for the Violins 1s 6d

MUSICK for the HARPSICORD or SPINNET

Signr Baptis Draghi Lessons for ye Harpsicord 5s 0d

Mr Henr Purcells Lessons for the Harpsicord 2s 6d

Dr Blows Lessons for the Harpsicord 1s 6d

Dr Blows psalms set full for the Organ 1s 6d

The Song Tunes in Camilla for ye Harpsicrd 3s 0d

The first book of the Ladys Banquet 2s 0d

The 2d book of the Ladys Banquet 2s 6d

Dupars Lessons for the Harpsicord 2s 6d

Ld Birons Lessons for the Harpsicord 1s 6d

Aires & Lessons for ye Harpsicord by Sevr. mr. 1s 6d

Mr Kellers new Edition of rules for a through Bass 1s 6d

The monthly mercury of Lessons for ye Harpsicord 0s 6d

Discussion

The first thing I noticed here is the title: A Catalogue of English and Italian Musick for Violins and Flutes. This clearly indicates the tastes of the London public, to whom Walsh was hoping to appeal: English and Italian repertory. The Italian and English names of some of the composers of course reflect these tastes.

On closer inspection, though, alongside Italian composers such as Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713) and Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni (1671–1750/51) and English composers such as Purcell, William Croft (1678–1727) and John Blow (1648/49–1708), we also see some who do not fall into either category – Johann Christoph Pepusch (1667–1752) and Johann Christoph Pez (1664–1716) were both German, and James Paisible (c.1656–1721) and Charles Dieupart (‘Dupar’) (after 1667–c.1740) were French (although Pepusch, Paisible and Dieupart had all settled in England). So what did Walsh mean by ‘English and Italian Musick’? We can only assume that he is referring to repertory in the English or Italian style as here English songs and dances are noted alongside Italian sonatas.

The catalogue primarily lists music for violin or flute and the harpsichord or spinet (a smaller form of harpsichord), in various combinations. The ‘flute’ referred to here was in fact the recorder – the instrument we now call the flute was known to eighteenth-century Londoners as the ‘German flute’. The instruments that dominate Walsh’s catalogue – recorder, violin and harpsichord – were extremely popular with amateur musicians during the early eighteenth century for domestic music-making. It was presumably this kind of clientele whom Walsh hoped to attract with this catalogue.

3.3 Corelli and the London audience

You are now going to focus on one of the Italian composers listed in Walsh’s catalogue: Arcangelo Corelli. Early in his career, Corelli had settled in Rome under the patronage of Cardinal Benedetto Pamphili, and then Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni. His acclaim as a violinist and composer spread throughout Europe, aided by the surge in music publishing at that time. Beginning with the publication of his trio sonatas (Opus 1) in Rome in 1681, the immense popularity of his music saw numerous reprints of his works produced during his lifetime on an unprecedented scale.

Corelli’s music was particularly well received in England. Unlike on the Continent, where interest in his music eventually waned, Corelli’s repertory continued to be performed in the English capital throughout the eighteenth century, both in the concerts of professional musicians and by amateurs at home. Many of the Italian instrumentalists who performed in London’s concert halls – Pietro Castrucci (1679–1752) and Francesco Geminiani (c.1687–1762) to name but two – had been taught by Corelli himself and used this association to widen their appeal to the English audience. A number of composers resident in London – English and Italian – produced new editions of Corelli’s works: both Geminiani and the English composer Obadiah Shuttleworth (c.1700–1734) adapted Corelli’s early sonatas for larger ensembles – and the influence of Corelli’s style is evident in many of the instrumental works composed during this period (Edwards, 1976, pp. 51–2, 70).

Activity 6

Look again at Walsh’s catalogue of c.1710 (Figure 5). How many of Corelli’s works are listed here? What does this tell us about the extent of the popularity of his repertory?

Discussion

There are eight items by Corelli listed in the catalogue:

- ‘Corellis 1st Collection for 2 Flutes and a Bass’

- ‘Corellis 2d Collection for 2 Flutes and a Bass’

- ‘Corellis Solos for a Flute and a Bass’

- ‘Corellis opera primo’

- ‘Corellis opera Secundo’

- ‘Corellis opera Terza’

- ‘Corellis opera Quorto’

- ‘12 Solos by Arcangelo Corelli’.

To me, this broad selection of works by Corelli reflects the appeal of his compositions to the London audience. Walsh could count on the fact that Corelli’s music would sell well and therefore advertised several of these works in his catalogue of publications.

Corelli may have been hugely popular but this was not owing to an extensive repertory: his published output consisted solely of music for strings and continuo (the bass line above which instrumentalists would improvise a chordal accompaniment – also known as ‘basso continuo’ and ‘thoroughbass’). His work appeared in six sets: Opuses 1 to 4 (the ‘opera primo’, ‘secundo’, ‘terza’ and ‘quorto’ in Walsh’s catalogue) were trio sonatas (i.e. pieces for two solo violins above a continuo); Opus 5 was a set of solo sonatas for violin and continuo; and Opus 6 was a series of concerti grossi (singular concerto grosso). A concerto grosso is an orchestral work in which a larger group, usually of string instruments (the ‘ripieno’ or ‘concerto grosso’), alternate with a smaller group of soloists (the ‘concertino’, also usually string instruments – in Corelli’s case, two violins and a cello) (Edwards, 1976, p. 52). Following their initial publication in Rome, new editions were hastily printed in other centres, including London, sometimes arranged for other instruments, as is reflected in Walsh’s listings of music by Corelli for flute (i.e. recorder).

3.4 John Walsh, Estienne Roger and Corelli’s solo sonatas

In this case study you are going to focus on Walsh’s publications of Corelli’s solo sonatas for violin and continuo – his Opus 5. These were the first works by Corelli to be published by Walsh and became the most popular of all his sonatas. We therefore find that several editions of the pieces appeared during the eighteenth century, in various forms. You are going to look at their early reception at the start of the eighteenth century. The sonatas were originally published by Gasparo Pietro Santa in Rome in 1700 – the dedication is dated 1 January – and editions in Amsterdam and London soon followed. Walsh was not alone in his plans to sell Corelli’s music in London and he therefore had to vie with rival publishers and booksellers. His main competitor in this respect seems to have been the prolific Amsterdam music publisher Estienne Roger (1665/66–1722). Roger’s output boasted an international repertory that was distributed by agents in cities across Europe, including one in London – the French bookseller François Vaillant (Rasch, 1996, pp. 398–400).

Activity 7

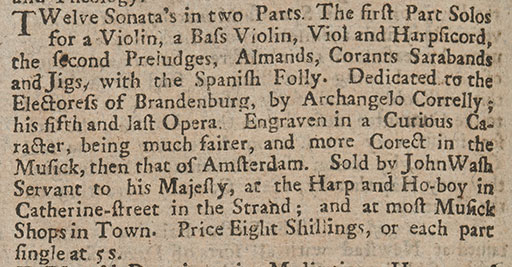

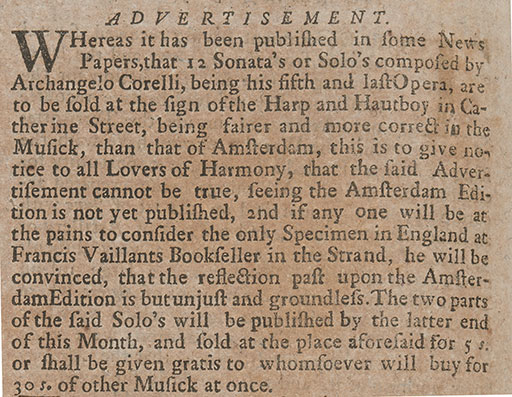

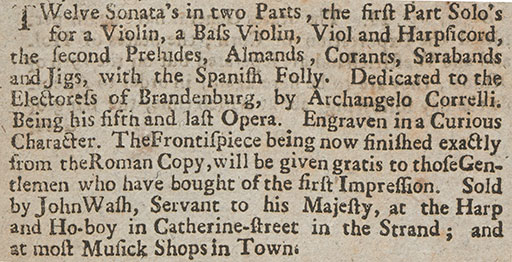

In this activity you will look at a number of London newspaper adverts to gain a sense of how Roger/Vaillant and Walsh competed for sales of the first English and Amsterdam editions of Corelli’s solo sonatas. Vaillant had initially placed an advert for Roger’s publication of the sonatas on 27 August 1700, and Walsh’s response, on 31 August, is the advert presented in Figure 6. This swift exchange of notices continued with Vaillant’s response to Walsh on 3 September (Figure 7), and another notice placed by Walsh a few weeks later, on 21 September (Figure 8). As you look at the three advertisements, jot down how you think they were trying to appeal to the London audience and to what extent the rivalry between Walsh and Roger might have affected the appearance and quality of their publications.

This is an advertisement from a London newspaper, employing conventions of spelling and capitalisation characteristic of the early eighteenth century. In one instance, a price is indicated by a numeral (5) followed by a lower-case letter ‘s’, indicating 5 shillings. The text reads as follows:

Twelve Sonata’s in two Parts. The first Part Solos for a Violin, a Bass Violin, Viol and Harpsicord, the second Preludges, Almands, Corants Sarabands and Jigs with the Spanish Folly. Dedicated to the Electoress of Brandenburg, by Archangelo Correlly; his fifth and last Opera. Engraven in a Curious character, being much fairer, and more Corect in the Musick, then that of Amsterdam. Sold by John Wash Servant to his Majesty, at the Harp and Ho-boy in Catherine-street in the Strand; and at most Musick Shops in Town. Price Eight Shillings, or each part single at 5s.

This is an advertisement from a London newspaper, employing conventions of spelling and capitalisation characteristic of the early eighteenth century. Prices are indicated by numerals followed by the lower-case letter ‘s’ to indicate a particular number of shillings. The text reads as follows:

ADVERTISEMENT.

Whereas it has been published in some News Papers, that 12 Sonata’s or Solo’s composed by Archangelo Corelli, being his fifth and last Opera, are to be sold at the sign of the Harp and Hautboy in Catherine Street, being fairer and more correct in the Musick, than that of Amsterdam, this is to give notice to all Lovers of Harmony, that the said Advertisement cannot be true, seeing the Amsterdam Edition is not yet published, 2nd if any one will be at the pains to consider the only Specimen in England at Francis Vaillants Bookseller in the Strand, he will be convinced, that the reflection past upon the Amsterdam Edition is but unjust and groundless. The two parts of the said Solo’s will be published by the latter end of this Month, and sold at the place aforesaid for 5s. or shall be given gratis to whomsoever will buy for 30s. of other Musick at once.

This is an advertisement from a London newspaper, employing conventions of spelling and capitalisation characteristic of the early eighteenth century. The text reads as follows:

Twelve Sonata’s in two Parts, the first Part Solo’s for a Violin, a Bass Violin, Viol and Harpsicord, the second Preludes, Almands, Corants, Sarabands and Jigs, with the Spanish Folly. Dedicated to the Electoress of Brandenburg, by Archangelo Correlli. Being his fifth and last Opera. Engraven in a Curious Character. The Frontispiece being now finished exactly from the Roman Copy, will be given gratis to those Gentlemen who have bought of the first Impression. Sold by John Wash, Servant to his Majesty, at the Harp and Ho-boy in Catherine-street in the Strand; and at most Musick Shops in Town.

Discussion

The rivalry of Walsh and Vaillant and their attempts to win customers is plain to see in Walsh’s claims that his edition is better than that of Roger (the Amsterdam edition sold by Vaillant), and Vaillant’s dismissal of this statement as nonsense. Links to the Italian original, such as Walsh’s offer of the frontispiece of the Roman edition, are clear attempts to appeal to lovers of Italian culture who wished to have an ‘authentic’ copy of the great Corelli’s work with its elitist associations – Corelli’s dedication to the Electress of Brandenburg, mentioned in Walsh’s adverts, was also copied from the original Italian edition. The close rivalry between Walsh and Roger can only have resulted in their endeavours to improve their editions in order to appeal to the music-loving public.

Following the publication of Opus 5, Walsh proceeded to publish the remainder of Corelli’s works for the London audience. His rivalry with other publishers is clear in his quick retaliation to their new editions with publications of his own, and in his issue and reissue of his editions. He also aimed for a broader audience by publishing arrangements of Opus 5 for the instruments commonly played by amateurs in their homes: ‘Six solos for a flute and bass’ and ‘Six setts of aires for two flutes and a bass’ were issued in 1702, and an arrangement for harpsichord followed in 1704.

3.5 Walsh’s editions of Corelli’s Opus 5

Let’s now turn to two of Walsh’s editions of Corelli’s solo sonatas: his first edition (advertised above, Figures 6 and 8; see Score 1) and a later edition of c.1711 (see Score 2).

Activity 8

Look at the title pages of the two editions (Score 1 and Score 2). You might find it helpful to open these in a new window or tab. What differences do you notice in their appearance? How do you think each edition might have appealed to the London public?

Discussion

The title pages are indeed very different: Walsh’s initial edition (Score 1) is in Italian, and is faithful to the original Italian print apart from the insertion of his imprint at the bottom of the page. The Italian title page lists the instruments of the work (‘violino e violone o cimbalo’ – violin and bass violin or harpsichord), and boasts that it is dedicated to Sophie Charlotte, Electress of Brandenburg (‘dedicate all Altezza Serenissima Electorale di Sofia Charlotta Electrice di Brandenburgo’). It states that it is by Arcangelo Corelli of Fusignano (a small town between Bologna and Ravenna) and that it is his fifth opus (‘Opera Quinta’). Walsh’s later edition (Score 2) has a title page in English: ‘XII Sonata’s or Solo’s for a Violin a Bass Violin or Harpsicord Compos’d by Arcangelo Corelli. His fifth Opera. This Edition has ye advantage of haveing ye Graces to all ye Adagio’s and other places where the Author thought proper.’ Both title pages therefore claim that each edition is linked in some way to Corelli himself: the first edition faithfully reproduces the Italian edition’s title page (and also, on the following page, its dedication – not reproduced in Score 1) while the later edition of c.1711 claims to include ‘Graces’ (i.e. ornamentation) allegedly as Corelli intended. Both would have therefore appealed to enthusiasts of Italian music, the later edition in particular to those who wished their performances to truly reflect Corelli’s style.

Activity 9

Now let’s consider the music itself. Look at the opening of the first sonata in the collection and compare the two editions (Score 1 and Score 2) while listening to Track 2. You might find it helpful to open these in a new window or tab. How do the editions differ?

Discussion

The score in the later edition is far more detailed, with embellishments printed for the performer, whereas the earlier edition presents the basic melody and leaves any decoration down to the performer’s own interpretation. In both editions the accompanying bass lines are simple, again allowing the performer a certain amount of freedom.

You may have also noticed that the numbers printed above some of the notes in the bass line of the earlier edition are missing in the later publication. This is known as a figured bass and signified the intervals to be played above the bass line in the improvisation of an accompaniment. The missing figures here might just be a printing error – the keyboard part still includes the occasional instructions ‘Tasto solo’ (‘single key only’), indicating that the performer should not add chords to the bass line at these points, and presumably that elsewhere, figured bass principles would apply.

Activity 10

Now compare the opening of the sonata in Walsh’s later edition (Score 2) with the same section of music in Roger’s Amsterdam publication of 1710 (Score 3). You might find it helpful to open these in a new window or tab. Can you spot any differences between the two? What about in the suggested embellishments presented in the scores?

Discussion

Apart from differences in the fonts of any text in the editions, these seem to be identical. The formats of the pages match exactly, with line and page breaks in the same places. They also have exactly the same suggested decorations and are both lacking figured bass markings.

These similarities are due to the fact that Walsh had reprinted Roger’s edition for the London audience under his own (Walsh’s) name. This unauthorised reprinting of publications was quite common in the eighteenth century as there were fewer restrictions on publishing practices, especially when works were printed outside the country of origin (the Netherlands in this case). Walsh in fact reprinted numerous editions for the London audience from Roger’s publications, and therefore benefited from Roger’s prolific output. Roger likewise based some of his own editions on Walsh’s, although to a much lesser extent, and focused on works by composers based in London that might be otherwise unavailable on the continent (Rasch, 1996, pp. 401–2).

Walsh’s publications of Corelli’s Opus 5 therefore clearly reflect his intentions to meet the demands of the elitist London public who wished to own and perform the Italian repertory they had encountered during their Grand Tours of Europe. Walsh’s talent as a printer-publisher is not only apparent in the format of his editions, but also in his clever use of Roger’s publications, and his wording of advertisements and catalogues that aimed to appeal to his customers. Walsh’s output, and his rivalry with Vaillant and Roger, testify to the great popularity of Corelli’s music during the early eighteenth century and the need to make this repertory, along with other favourite works, easily available to London’s high society.

4 Music recordings of twentieth-century America

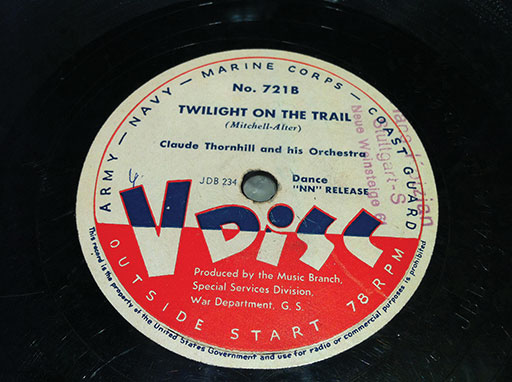

In this third and final case study you will look at recordings produced in America during the mid-twentieth century to see how their format and content were influenced by their intended audience. You will focus here on the years surrounding America’s involvement in the Second World War. By that time, 78 rpm records were widely available to consumers in the USA, allowing them to enjoy a variety of music in the home. This case study will however look beyond the commercial recordings purchased by civilians to focus on the records produced as part of the ‘V-Disc’ programme for American troops serving abroad (the ‘V’ stood for ‘Victory’).

4.1 The V-Disc programme

This is a photograph of a V-Disc label on a vinyl record. The picture shows the centre of the record so the edges cannot be seen. The record’s circular label has the large capitalised title ‘V Disc’ across the centre with the top half of the title in blue against a white background, and the bottom half of the title in white against a red background. The top half of the label, with the white background, has the text ‘Army – Navy – Marine Corps – Coast Guard’ capitalised in blue along the circular edge of the label. Beneath this, in the centre of this half of the label, is the text, in blue: ‘No. 7218’, then underneath this ‘Twilight on the Trail’, then ‘Claude Thornhill and his Orchestra’ and beneath this, ‘Dance’ and ‘‘NN’ Release’. The bottom-half of the label with the red background has beneath the ‘V Disc’ title, in white, ‘Produced by the Music Branch Special Services Division War Department’. Around the circular edge of this half of the label is the capitalised text, in white, ‘outside start 78rpm’.

Music and entertainment played an important part in maintaining American troops’ morale while they were stationed abroad. Although America did not join the Allies until 1941, a Morale Branch had been created by the American military as early as 1940, which led to the establishment of the Armed Forces Radio Service (AFRS) and the Music Section, from which the V-Disc programme would eventually derive. The AFRS was responsible for the broadcast of educational and information programmes to those overseas and also for the distribution of ‘B’ kits, which consisted of radios, phonographs and 78 rpm records. However, this supply of records encountered a setback in July 1942, which contributed to the establishment of the V-Disc label: a recording ban was introduced by the American Federation of Musicians (AFM), owing to recording companies’ refusal to pay royalties to musicians for every record sold, and for their use in jukeboxes and radio broadcasts.

As requests for current recordings continued to arrive from servicemen overseas, the Army set up a programme through which records would be made specifically for the troops. This was enabled by the AFM’s agreement to waive any fees or royalties in exchange for the Army’s promise that the recordings would only be distributed to the military, and destroyed once hostilities ended. The V-Disc label (bearing a distinctive label of red, white and blue) thus began production, at first for the Army alone, and joined by the Navy and Marine Corps in 1944. Every month, V-Disc kits of thirty records, together with questionnaires for soldiers’ music requests, were distributed to those serving in Europe and the Pacific. More than eight million records were sent to troops stationed abroad over the course of the programme, from October 1943 to May 1949, when, owing to less demand, the scheme came to an end (Miller, 2014; Sears, 1980, pp. xxiii–xci).

4.2 The form of V-Discs

You are now going to consider how the V-Discs compared in form with their commercial counterparts. At the time of their production, the standard 10-inch and 12-inch 78 rpm commercial records normally contained around three to four minutes of music per side. V-Discs on the other hand, also at 12 inches in diameter but with a greater number of grooves per inch, had a potentially longer playing time on each side – up to around six and a half minutes. Commercial records were produced from shellac – a material that was anti-abrasive yet fragile. However, this was in short supply during the war and not very practical; records often arrived overseas broken into several pieces. V-Discs were therefore eventually made from the harder wearing Vinylite, which was more flexible and not as fragile as shellac. When stocks of this also diminished, a similarly robust substitute, Formvar, was adopted for the records (Sears, 1980, pp. lxix, lxxv).

4.3 The content of V-Discs

V-Discs contained various kinds of music. This included material taken from radio broadcasts, commercial records and concert recordings, as well as numerous performances recorded especially for the programme in venues in New York and Los Angeles. The range of music included classical, jazz and swing, film and musical soundtracks, and country music. Many of the foremost musicians of the day contributed to the programme, providing performances and recording messages for the troops; Bing Crosby (1903–1977), Frank Sinatra (1915–1998), Glenn Miller (1904–1944), Benny Goodman (1909–1986) and Tommy Dorsey (1905–1956) were among the most popular. In line with the wishes of the servicemen, the records gradually contained more and more recent recordings. As the musicians’ recording ban meant that V-Disc was the only label to release new material during this period, the programme provides unique insights into the popular pieces at that time, both at home in America, and to the troops overseas (Young and Young, 2008, pp. 101–2).

Activity 11

How do you think the longer playing time on V-Discs would have allowed greater flexibility in terms of the music being distributed? Consider here improvisatory music such as jazz, and also lengthier pieces such as classical works.

Discussion

The extended playing time on records enabled lengthier pieces to be played in full. Longer classical pieces which might have been cut or divided between sides of shorter commercial records could fit more comfortably on the longer V-Discs. This freedom from the usual time restrictions was particularly valuable for performances of jazz, where musicians could improvise more freely and for longer, and where arrangements by big bands could also be extended.

The lack of the tensions and contractual obligations associated with previous affiliations to specific record companies (abandoned during the recording ban) also allowed musicians who were previously unable to perform together to collaborate for the first time. These conditions resulted in the V-Disc label capturing numerous unique performances, including many by jazz musicians.

Activity 12

Listen to the extract of the recording for V-Disc of ‘Oh! Baby’ (Track 3), introduced by the guitarist Eddie Condon (1905–1973) and performed by Bobby Hackett (1915–1976) (cornet), Michael ‘Peanuts’ Hucko (1918–2003) (clarinet), Ernie Caceres (1911–1971) (baritone saxophone), Robert ‘Cutty’ Cutshall (1911–1968) (trombone), Irving Manning (1918–2006) (double bass), Charlie Queener (1921–1997) (piano) and Morey Feld (1915–1971) (drums). Consider the extent to which recordings in general can contribute to our knowledge of performance practices, especially with regard to unnotated musical practices such as in jazz. In what way is this V-Disc recording specifically aimed at the troops abroad?

Discussion

This recording communicates directly with its audience through Eddie Condon’s spoken greeting to the troops overseas and provides them with an opportunity to listen to music that was strongly associated with America (and was developing apace back there).

The recording provides us with valuable information about a performance that is otherwise undocumented: it identifies who the musicians were (an aspect that is sometimes hard to establish in recordings of jazz) and the relationship between these individuals as they play. As a seemingly unique, spontaneous performance not produced for financial gain, the recording also provides particularly important insights into jazz practices at that time, such as improvisation (which was further facilitated by the more relaxed circumstances of the V-Disc recordings).

This would also be the case for many of the other performances recorded especially for the programme: unique performances of popular music and even of classical works can provide information about performance trends at that time.

4.4 The meaning of V-Discs

Besides the patriotic appearance of the V-Disc label, it was of course the content of these records that held such a valuable message for the American troops stationed abroad during and immediately following the Second World War. Let’s look at two testimonials relating to the production and reception of the records to gain a sense of the reaction of those involved in the programme itself, and of its audience overseas.

Lieutenant Edmond DiGiannantonio (1917–2000), Navy representative for the V-Disc programme:

What initially appeared to be an unimportant assignment turned out to be one that helped to bridge the gap between the home front and the millions of GIs overseas. It soon became apparent that the Army V-Disc group was an assembly of very talented individuals, imbued with a sense of pride in what they turned out for our troops. The product was a reflection of America’s way of life, portrayed in its music. The high calibre of the artistic selections and the technical quality of the V-Discs made this program one of the most important morale sustainers of the war. The V-Discs were a tie to home and presented an almost instantaneous projection of what was transpiring across the musical spectrum in our country.

- Drummer and bandleader Spike Jones (1911–1965) to Robert Vincent (1898–1985), founder of the V-Disc programme, 7 February 1945:

It just occurred to me that I never did tell you before this what an impression V-Discs made upon me and all the rest of us City Slickers during our recent overseas tour for USC. We visited many, many places in England and France, and everywhere we went, we saw the men playing V-Discs. We heard them on the boat going over and on the boat coming home; we played them on the LST boat crossing the channel, and we saw them being played everywhere in France, including in fox-holes! I can state definitely – and I know the fellows agree with me here – that of all the music morale builders, including the various transcribed shows that go overseas, V-Discs are easily the most popular and most effective medium for giving our men the music they want and need to keep going.

Activity 13

Based on these two accounts, what did the individuals involved in the running of the programme feel about it? What about the troops who received the discs? According to these reports, what meaning did the V-Discs have to them?

Discussion

The individuals involved in the production of V-Discs (such as DiGiannantonio and Spike Jones) were obviously proud of the programme and the support it provided to the troops. The popularity of the scheme with the soldiers is clearly expressed in Jones’s report, as is the significance of the V-Discs as a medium for boosting morale. DiGiannantonio emphasises that the music on the discs represented the American way of life to the servicemen, keeping them up-to-date with music in America while they were stationed abroad and providing an audible link to their home.

4.5 Meanings of V-Disc music

To demonstrate the meaning invested in V-Discs by the troops, you are going to look at two popular songs of the time. These have been selected from the huge range of repertory made available through the programme as they might have held particular resonance for the American servicemen.

Activity 14

Listen to extracts from the following two songs (some details of each song’s context are provided):

- ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ (Track 4), performed by Frank Sinatra. This song is originally from the Broadway musical Carousel (1945) by Rodgers and Hammerstein, where it is first performed by Nettie Fowler to comfort Julie Jordan after her husband commits suicide. It is sung again at the end of the musical, to give hope for the future at the graduation ceremony of Julie’s daughter Louise (Hischak, 2007, p. 322). The song was hugely popular beyond the musical; following the release of the soundtrack of the Broadway production, Sinatra was the first artist to record the song (Columbia Records, Los Angeles, 1 May 1945), which reached ninth place in the Billboard chart of September 1945, and was issued on V-Disc in November 1945 (Sears, 1980, pp. 809, 1107).

- ‘Beyond the Blue Horizon’ (Track 5), recorded by Martha Tilton (1915–2006) at the RCA Victor Studios, New York, on 10 May 1945 and released on V-Disc in October that year (Sears, 1980, pp. 887–8, 1106). The song was also originally written for a musical: the film Monte Carlo (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1930). In the film, the song is performed by a countess (played by Jeanette MacDonald, 1903–1965) who leaves her wealthy fiancé and flees to Monte Carlo. She performs the song while on the train to Monte Carlo, waving to farmers in the fields who join her in song. In the musical, the song reflects the countess’s strength and her determination to overcome her financial difficulties. This theme was especially relevant to the American audience at the time of the film’s release during the Great Depression. MacDonald’s recording of the song was a top-ten hit in the USA (Furia and Lasser, 2006, p. 83; Bradley, 1996, p. 258).

How might overseas troops have interpreted the lyrics and mood of these songs?

Discussion

Both songs would have provided the servicemen with a musical link to America and a message of support from home. During the difficult period of the war and its immediate aftermath, the songs would have been invested with very personal meanings by listeners, which went beyond the original context and characters of each musical. Both songs retain the feelings conveyed in their settings in the two musicals: ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ communicates comfort in a rather sentimental way, while ‘Beyond the Blue Horizon’ is more upbeat and gives hope for the future. The feelings of comfort and hope would have been pertinent to the difficult circumstances of the troops, enhanced by the mood (sentimental or upbeat) of each song.

It is clear that, over the years, individuals and groups have attached their own meanings to these songs. As I mentioned above, ‘Beyond the Blue Horizon’ had originally become popular with those experiencing financial hardship during the Great Depression. ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’, on the other hand, has since become well-known as an anthem for football fans and especially for Liverpool Football Club, whose association with the song since the 1960s intensified after the 1989 Hillsborough disaster.

V-Discs are therefore a clear example of musical media which had their function and meaning defined by their recipients: the American troops abroad. The practicalities of supplying numerous records to individuals in diverse locations resulted in the development of the format of the records – in their longer playing time and the materials from which they were made. The meaning of these recordings to the troops is patently clear, from the name of the scheme itself (‘V’ for ‘Victory’) and the red, white and blue record label, to the songs that boosted the troops’ morale and provided a musical link to their lives back home in America.

Conclusion

In this free course you have considered some of the main ways in which music has been transmitted over the years and continues to be passed on to us today, through oral/aural communication, notation (in manuscript or print) and recordings. You have studied how each musical source represents merely one instance of potentially numerous ways of communicating a single work: by looking at ‘Happy Birthday to You’, you observed how the means by which a specific piece is transmitted can change over the years and how these changes can be closely linked to the different meanings and functions assigned to a work. Through your study of three examples of musical media from different historical periods and geographical locations, you were able to further assess how the form of a musical source can reflect both the context in which it was created (particularly with regard to social and technological factors) and, more specifically, the recipients for whom these manuscripts, prints and recordings were produced.

Glossary

- chanson

- A song set to French words; chiefly a secular French polyphonic song of the Middle Ages/Renaissance.

- chansonnier

- A book (manuscript or printed) containing principally chansons (French lyric poetry), either in text form or set to music.

- concerto grosso (pl. concerti grossi)

- A form of concerto, primarily of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, consisting of several movements in which a larger group of instruments (‘ripieno’ or ‘concerto grosso’) alternates with a group of soloists (the ‘concertino’).

- continuo

- The bass line upon which instrumentalists improvise a chordal accompaniment. Continuo is primarily associated with the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It was performed by various combinations of instruments, which could include keyboards (e.g. organ, harpsichord), plucked strings (e.g. theorbo, harp, guitar, harp) and/or bowed strings (e.g. bass viol, cello). Also known as ‘basso continuo’ and ‘thoroughbass’.

- figured bass

- A bass line with figures and symbols indicating the intervals to be played above this. Figured bass is associated with the basso continuo practices of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

- folio

- A leaf of paper in a book or manuscript numbered on the front only. The front of the leaf is called the ‘recto’ (abbreviated ‘r’ after the folio number – e.g. ‘fo. 2r’) and the back is the ‘verso’ (abbreviated ‘v’).

- motet

- A polyphonic vocal composition, primarily of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, usually setting a Latin sacred text.

- solo sonata

- A form of sonata for solo instrument (usually violin) and continuo prevalent from the mid-seventeenth to mid-eighteenth centuries.

- trio sonata

- A sonata for (usually) two melody instruments and continuo, prevalent during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Helen Coffey

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Course image

Photo: © Walker Art Gallery, National Museums Liverpool/Bridgeman Images.

Scores

Score 1: Photo: By permission of the British Library.

Score 2: Photo: By permission of the British Library.

Score 3: Photo: By permission of the British Library.

Images

Figure 1: Photo: By permission of the British Library.

Figure 2: Photo: © Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, UK/Bridgeman Images.

Figure 3: Photo: Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique.

Figure 4: Photo: ÖNB/Wien.

Figure 5: Photo: The British Library Board

Figure 6: Photo: By permission of the British Library.

Figure 7: Photo: By permission of the British Library.

Figure 8: Photo: By permission of the British Library.

Figure 9: Photo: Columbia University.

Audio

Track 1: La Rue, Ave sanctissima Maria (extract). Early Music Consort of London, cond. David Munrow. The Art of the Netherlands. EMI CMS 7 64215 2, recorded 1976, CD issued 1992, CD 2, Track 13.

Track 2: Corelli, Violin Sonata in D Major, Op. 5 No. 1, Grave – Allegro (extract). Sigiswald Kuijken (violin), Wieland Kuijken (cello), Robert Kohnen (harpsichord). Corelli: Violin Sonatas, Op. 5, Nos. 1, 3, 6, 11, 12. Accent ACC10033, Track 6.

Track 3: Bobby Hackett, ‘Oh! Baby’ (extract). Bobby Hackett (cornet), Eddie Condon (guitar), Michael ‘Peanuts’ Hucko (clarinet), Ernie Caceres (baritone saxophone), Robert ‘Cutty’ Cutshall (trombone), Irving Manning (double bass), Charlie Queener (piano), Morey Feld (drums). Bob Haggart and Bobby Hackett: V-Disc Parties 1943–1948. Jazz Unlimited/Storyville 709397, 2005, Track 7.

Track 4: Frank Sinatra, ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ (Rogers and Hammerstein) (extract). The Real Complete Columbia Years V-Discs. The Jazz Factory JFCD 22855, 2003, CD 2, Track 14.

Track 5: Martha Tilton, ‘Beyond the Blue Horizon’ (extract). Martha Tilton & Her V Disc Play Fellows. Martha Tilton Greatest Hits. Stardust Records B00C7CLQPC, 2008, Track 13.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University