The MMR vaccine: Public health, private fears

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 19 April 2024, 1:34 AM

The MMR vaccine: Public health, private fears

Introduction

The MMR dispute is of enormous public significance and this course helps unravel why this has been an area of such dispute.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of postgraduate study in Science.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand more of the scientific factors that relate to the dispute about the safety of the MMR vaccine in the UK

assess the strength of arguments for and against the use of the MMR vaccine

show how issues of risk, trust, communication and media representation of science and medicine have a strong bearing on public perception of the MMR vaccine

explain why there is such a strong consensus amongst the medical profession testifying to the safety of the MMR vaccine.

1 The MMR controversy

The furore over the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccination has rapidly escalated into a landmark controversy in the UK. Since the suggestion in 1998 by Dr Andrew Wakefield that MMR might be implicated as a cause of autism, a steady stream of claim and counterclaim has been played out in the scientific press, and newspaper headlines have see-sawed between condemnation and commendation (see the chronicle of events outlined in Box 1). More generally, the MMR debate illustrates that public health programmes are frequently underpinned by a strong ‘reliance on science’, which may not be an effective persuasive strategy for its target audience. Instead, this course will show that the public have witnessed an element of dissent within the scientific and medical establishments. Furthermore, the political and scientific management of this conflict, and a reluctance to acknowledge the social context within which it has arisen, have given the debate a longevity and potency perhaps far beyond that which the scientific arguments themselves warrant.

MMR vaccine consists of a freeze-dried preparation of live but weakened (attenuated) virus particles, intended to provoke recognition of the measles, mumps and rubella viruses by the body's immune system but not cause any symptoms of the diseases themselves. The vaccine is usually given in two doses, both by injection. The first dose is given to babies aged 12–15 months, and the second (a ‘booster’) is given at school age, intended to protect those children (about 5–10%) that did not respond to the first dose. The triple vaccination programme was introduced in the UK in 1988. It replaced the single vaccine given to babies for measles and a vaccination for rubella given to teenage girls. Mumps was not previously widely vaccinated against.

In this course, we'll explore why the MMR controversy has loomed so large in public consciousness. We'll have a look at the effects of media coverage, and see how social factors are inextricable from science when it comes to assessing risk. Like many other parents of young children, I have had to take a difficult decision about whether or not to trust the MMR vaccine. The scientific consensus is almost unanimous against an association between MMR and autism, so why do parents agonise about it? Is this a symptom of wider public anxiety about scientific pronouncements on public health, and is this uneasiness justified?

Box 1 Chronicle of some of the main events in the MMR controversy

| October 1988 | The MMR vaccine replaces single vaccines for measles and rubella in the UK. |

| April 1993 | Andrew Wakefield claims to have established a link between measles and Crohn's disease (an intestinal disorder), but further studies could not confirm this. |

| 28 February 1998 | Wakefield and 12 co-authors publish an early report in The Lancet showing intestinal inflammation in 12 children with developmental disorders. Wakefield announces his concern about links between MMR and autism at a press conference. |

| 23 March 1998 | Meeting of 37 experts by Medical Research Council reviews published and unpublished evidence and concludes there is no link between MMR and autism. |

| 2 May 1998 | Finnish study published in which reported adverse reactions to the MMR vaccine between 1988 and 1996 revealed no association between MMR and autism. |

| 12 June 1999 | Epidemiological study of 498 cases of autism in eight North Thames health districts finds that there was no sudden step-up increase in diagnoses after the introduction of MMR in 1998 and no developmental regression clustered after vaccination. |

| 6 April 2000 | Wakefield testifies in support of his MMR–autism hypothesis to a US Congressional Hearing. |

| December 2000 | Wakefield publishes a paper entitled ‘MMR vaccine: through a glass, darkly’, criticising safety procedures when MMR was first introduced. |

| 21 January 2001 | Wakefield discloses to the Telegraph that he has seen 170 cases of ‘a new syndrome of autism’, with the majority of cases backed by documentary evidence of regression following vaccination. He claims that regulators have failed to adequately address safety of the MMR vaccine. |

| March 2001 | Department of Health drops advertising campaign to promote MMR in the face of criticism that the money would be better spent on research into autism. |

| 9 June 2001 | Lothian division of the British Medical Association (BMA) requests the BMA to back single vaccines as an alternative for parents who refuse the MMR. |

| 30 November 2001 | Wakefield ‘asked to resign’ from Royal Free Hospital. |

| 13 December 2001 | Review by Medical Research Council into autism finds that the number of cases has increased (6 in 1000 children), but this is largely due to increased recognition and changing definitions of autism. The report finds no evidence of a link with MMR. |

| 19 December 2001 | During Prime Minister's Questions, MP Julie Kirkbride asks Mr Blair whether his son Leo had been immunised with MMR. Mr Blair declines to answer on privacy grounds. |

| 3 February 2002 | BBC TV Panorama special presents a largely sympathetic account of Wakefield's hypothesis. Wakefield claims that research has found measles in the guts of 75 of 91 autistic children with bowel disease. |

| 19 June 2002 | Wakefield presents evidence to a US congressional committee claiming that the measles virus identified in the guts of autistic children had been identified by a team led by John O'Leary as originating from the vaccine. The technique was subsequently criticised as being too crude to discriminate wild infection from the vaccine. |

| 2 July 2002 | Ken Livingstone, Mayor of London, announces that he will opt for single vaccines for his as yet unborn child. |

| 7 November 2002 | Danish study of half a million infants finds that autism is no more prevalent in vaccinated vs unvaccinated children. |

| 13 June 2003 | High Court rules that children of two estranged couples should have the MMR vaccine, against the mothers' wishes. |

| 27 February 2004 | Parents who believe their children were damaged by MMR are refused legal aid funding to sue manufacturers of the vaccine. |

| 6 March 2004 | Ten of the 13 authors of the original Lancet paper issue a partial retraction. |

2 Background to the controversy

In February 1998, Andrew Wakefield and twelve co-authors published a study in The Lancet – a respected peer-reviewed medical journal. The paper was published with the highly technical, but seemingly innocuous, title: ‘Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children’. It was based on a study of twelve children who had been referred to Wakefield's clinic with gastrointestinal disease. Most of the children had a regressive form of autism in which they appeared to develop normally as infants, before losing acquired skills including communication.

In medical examinations the lining of the children's intestines all showed patchy inflammation. According to the authors, the findings seemed to support the hypothesis that a damaged intestine may, in some cases, trigger behavioural changes in children. The mechanism suggested for this in the Lancet paper relies on the ‘opioid excess’ hypothesis for autism. When peptides from food such as barley, rye and oats, and casein from dairy products, are not fully digested in the gut, they are absorbed and bind with peptidase enzymes. These enzymes usually break down the naturally occurring peptide opioids that function in the central nervous system. The hypothesis suggests that the consequential disruption of the central nervous system adversely influences brain development.

Wakefield's paper relates that the parents or the physicians of eight of the study's twelve children reported that behavioural problems started within two weeks of the MMR triple vaccine being administered. This evidence was purely anecdotal. In the discussion part of the paper, the authors acknowledge as much: ‘We did not prove an association between measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine and the syndrome described,’ and ‘Published evidence is inadequate to show whether there is a change in incidence or a link with measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine’ (Wakefield et al., 1998).

However, at a press conference to mark the publication of the paper, Wakefield told reporters that he believed that the three vaccines in MMR should be given separately. Investigative journalist Brian Deer (2004) recalls the occasion:

At the centre of the speakers’ table sat the principal author of the study, Dr Andrew Wakefield. Cutting a dashing and charismatic figure, the young gastroenterologist had a very different message to impart. Yes, it was just one study and yes, there was no proof, but he personally believed that action was needed. ‘One more case of this is too many,’ he declared. ‘It's a moral issue for me and I can't support the continued use of these three vaccines given in combination until this issue has been resolved.’ He wanted single jabs.

(Deer, Sunday Times, 22 February 2004)

Reading 1

Although the suggestion of a link between the MMR vaccine and autism was made at a press conference and was not explicitly part of the research paper, the study itself came under fire for its methodology and data interpretation. The question is often asked how such a contentious paper came to be published in the first place. Click on the following link to download a PDF of the original paper published in The Lancet (1998), 351, pp. 637–41 – http://briandeer.com/ mmr/ lancet-paper.pdf (accessed 6 September 2012). It will be useful to have this paper to hand as you now look at Reading 1 in detail. The chapter id entitled ‘The Lancet Paper’ from MMR and Autism: What Parents Need to Know by Dr Michael Fitzpatrick, which outlines the response of the scientific community to the controversy. The author, a general practitioner and himself a father of an autistic son, is a vociferous proponent of the MMR vaccine. As you read, keep a note of the categories of arguments that Fitzpatrick employs in his critique – for example, scientific,

Discussion

What strikes me as particularly significant from Fitzpatrick's account is that the circumstances surrounding the Lancet paper's publication highlighted the subjectivity of the process of deciding not only what scientific research gets done, but also which results get published and why. It is often said in science that ‘the facts speak for themselves’. The circumstances of research approval, publication and reaction to scientific investigations which have political, economic and social consequences seem to me to exemplify what a fallacy this is. The reading also highlights how complex the process is of testing a seemingly straightforward hypothesis in the ‘real world’ as opposed to carefully controlled laboratory conditions.

Fitzpatrick chronicles the barrage of experts stepping forward to criticise Wakefield's study and issue reassurances about the safety of MMR. In spite of this, the effects were dramatic. The Health Protection Agency monitors vaccination uptake in the UK: from a peak of 92% uptake in 1995–96, this figure dropped to below 80% by 2003 and was as low as 60% in some areas. There was a concomitant rise in cases of measles. In 2003, 442 cases of measles were reported: a threefold increase in the numbers reported in 1996. It was clear that a significant number of parents had decided not to immunise their children with the MMR vaccine.

3 Risk perception

At first glance, the public response to the risk of a link between MMR and autism appears to be wildly disproportionate. From a scientific point of view, an association is unsupported by major epidemiological studies involving vast numbers of participants. Neither has evidence been presented of a plausible biological mechanism. Common sense would seem to dictate that the claim to any link simply lacks credibility and well-informed parents should behave ‘rationally’ and allow their children to be immunised, or else run the very real risk of exposing children to potentially serious diseases (see Table 1).

| Disease | Symptoms | Complications |

|---|---|---|

| Measles | Fever, rash, cough, sore eyes, swollen glands, loss of appetite | Ear infection, pneumonia/bronchitis, convulsion, diarrhoea, meningitis, death |

| Mumps | Swollen glands, fever, headache, abdominal pain, loss of appetite | Swollen testicles, meningitis/encephalitis, pancreatitis, deafness, miscarriage |

| Rubella | Fever, headache, rash, sore eyes, cough, swollen glands, joint pains, loss of appetite | Encephalitis, bleeding disorders. In pregnancy: deafness, blindness, heart problems, brain damage in foetus |

These symptoms and complications are unpleasant at best and life-threatening at worst. Yet it may be worth considering the extent to which today's parents have witnessed the diseases of measles, mumps or rubella. A study by Gore et al. (1999) into the factors that affected parents' decisions to immunise found that in communities where infectious diseases were rarely witnessed, immunisations were often considered to be redundant.

Reading 2

Click to view Reading 2, Bellaby, P. (2003) ‘Communication and miscommunication of risk: understanding UK parents' attitudes to combined MMR vaccination’, BMJ, 327, pp. 725–28. Bellaby argues that parents' responses to the MMR controversy are not necessarily irrational. What factors does he use to support his argument?

Discussion

One of Bellaby's points is that ‘the case evokes cultural and social context rather than “economic man”’ (‘economic man’ is an economist-theory model of human behaviour, which presumes that people act entirely in their own self interest). He shows that context often proves decisive in decision making by parents about whether to allow their children to be immunised with the MMR vaccine.

Although risk is always a social evaluation, rather than a natural phenomenon that can be separated from its context, risk experts often refer to the qualitative aspects as ‘the social amplification of risk’. A combination of circumstances makes certain events seem more risky than the orthodox scientific assessment would have it. One of the main driving forces is the perception of ‘fright factors’. These are characteristics of a controversy that elevate levels of alarm. Bennett (1999) has summarised these ‘fright factors’. He argues that risks are generally more anxiety-inducing if they are perceived to:

-

be involuntary rather than voluntary

-

be inequitably distributed (some benefit while others are adversely affected)

-

be inescapable by taking personal precautions

-

arise from an unfamiliar or novel source

-

result from artificial rather than natural sources

-

cause hidden and irreversible damage

-

pose particular danger to small children or pregnant women, or to future generations

-

threaten a form of death or illness arousing particular dread

-

damage identifiable rather than anonymous victims

-

be poorly understood by science

-

be subject to contradictory statements from responsible sources.

Activity 1

Go through this list of ‘fright factors’ and note down which of them apply to MMR and why.

Discussion

It quickly becomes apparent that the MMR vaccine controversy rates very highly indeed on ‘fright factors’ compared with other types of risks that might, statistically, be more likely to occur. A scientific assessment of risk, which focuses on mathematical probabilities, often tends to ignore these ‘fright factors’, whereas public perceptions tend to prioritise them over statistical and experimental data.

Indeed, assessments of risk are rarely objective. Value judgements, impossible to measure scientifically, often frame individuals' reactions to risk. Thinking of your own response to risk, you might prioritise or downplay certain ‘fright factors’ in any one situation depending on your moral, political, ethical or religious stance.

Scientists have a tendency to frame risk in terms of effects on populations whereas lay people (non-experts, so to speak) tend to be concerned with individuals. This is particularly relevant to an issue such as immunisation where we can see immediately that there may be a tension between a scientific and a lay perspective. No vaccination is without some degree of risk to the individual, however small. Yet for a mass immunisation policy to work, a significant proportion of the population needs to be immunised to achieve ‘herd immunity’ (estimated to be 95% for MMR by the World Health Organization). Scientifically (and politically) the small risk of an adverse reaction is seen as a price worth paying. Most governments acknowledge the inherent unfairness of this. In Britain, in the event of a serious reaction, parents can apply for vaccine damage payments to compensate for ‘sacrificing’ their child's health for the public good. However, financial compensation is likely to be of little comfort to parents whose children have been disabled through vaccine damage.

As the collective memory of diseases like measles and mumps recedes, the risk of adverse effects comes into sharper focus. An appeal to social responsibility in maintaining herd immunity may matter less to parents who perceive the risk of autism to be greater than the risk of contracting measles or mumps. The benefits of protection conferred by immunisation and the risk taken of adverse effects is an individual one, but the risks of transmitting an infectious disease when herd immunity is not maintained are social as they extend to those beyond the MMR dissenters. Indeed, the groups most vulnerable to mumps, measles or rubella are babies too young to be immunised and teenagers whose vaccinations predated MMR, many of whom were not immunised for mumps.

Fitzpatrick (2004) provocatively speculates that for some parents the decision to refuse the MMR triple vaccine has little to do with medical science per se.

Middle class discontents became apparent around a range of political issues: fuel prices, student loans, blood sports and the invasion of Iraq. Yet MMR provided a focus for protest that was both intensely personal and highly political … The controversy over immunisation allowed scope for individual initiative, at least in the form of a gesture of defiance, which was generally lacking in the public sphere.

(Fitzpatrick, 2004, p. 56)

While, for some, withholding immunisation may have had an element of political defiance, for others it was the path of least resistance. Taking a child to be vaccinated is a distressing experience at the best of times. For parents uncertain about what to do, the balance easily tips in favour of postponing a decision or doing nothing (Scottish Executive, 2002).

The picture painted here is that the scientific consensus on the risk that the MMR triple vaccine causes autism is hugely disproportionate to the public perception of that risk – a perception that is influenced by a much wider range of factors. Parents might appreciate that mainstream scientific consensus is that the MMR triple vaccine poses a negligible risk, but these ‘informed dissenters’ may still decide not to immunise their children for a variety of personal or political reasons that have little to do with science.

4 Single vaccines – the middle way?

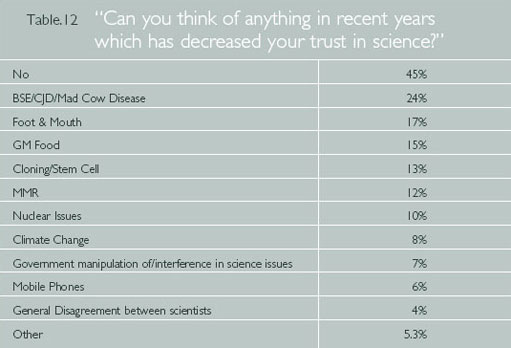

Much of the campaign surrounding doubts about the MMR vaccine has centred on a call to replace MMR with single vaccines. This is seen as part of a precautionary argument, just in case Wakefield turns out to be right about an association between the MMR vaccine and autism. After all, the spectre of government reassurances about the ‘safety’ of BSE-infected meat and the subsequent climb down still loom large in public consciousness. Comparisons to the BSE crisis were reinforced by Wakefield, who termed the intestinal inflammation he had found in autistic patients as ‘new variant inflammatory bowel disease’ – an unambiguous allusion to ‘new variant CJD’.

Wakefield's hypotheses for MMR-induced damage have always focused on the measles component of the vaccine. If he believes this, why should separate measles vaccine pose any less of a risk? His call for single vaccines is based on a notion that giving too many vaccines at once overloads the immune system. In some cases, it is claimed, the attenuated strain of the measles virus present in the vaccine causes chronic measles infection and leads to the ‘leaky gut’ which renders the developing brain susceptible to damage.

The hypothesis that the immune system is overloaded by combined childhood vaccines has never had scientific currency, but in light of the MMR controversy, a team of researchers led by Paul Offit re-examined the issue (Offit et al., 2002). Modern vaccines contain fewer antigens than in the past. Collectively, the immunisation programme recommended for infants in Britain exposes them to less than 100 antigens whereas the immune system is theoretically capable of responding to about 1010 antigens. Other studies tested the hypothesis that if the MMR vaccine did damage the immune system, an increased level of hospitalisation for infectious diseases would occur following the vaccine. Again, no association was found (Miller et al., 2003). It is, however, worth reflecting at this point on the difficulty in collecting and interpreting trends where there are a multiplicity of interdependent variables – a situation which confounds many epidemiological studies.

The main stance of the Department of Health has been that single vaccines expose children to the possibility of infection while waiting to complete the immunisation schedule. Fitzpatrick (2004) associates the momentum of the single-vaccines campaign with the Labour government's policies which have continuously emphasised parental choice, especially with regard to schools and hospitals. By not making available single vaccines as an alternative to MMR, the government's stance has been seen as an active denial of choice, counter to the policy of patient empowerment.

In stark contrast to the unwavering stance of the government, Wakefield is often portrayed as the ‘listening doctor’ in the press – an image he has taken care to cultivate. In response to criticism of the Lancet paper, he said: ‘the approach of the clinical scientists should reflect the first and most important lesson learnt as a medical student – to listen to the patient or the patient's parent, and they will tell you the answer’ (Wakefield, 1998).

In the battle for hearts and minds that characterises the MMR controversy, the sympathetic Wakefield clearly trumps the perceived heavy-handed authoritarian approach of the health establishment.

5 MMR and the media

5.1 Overview

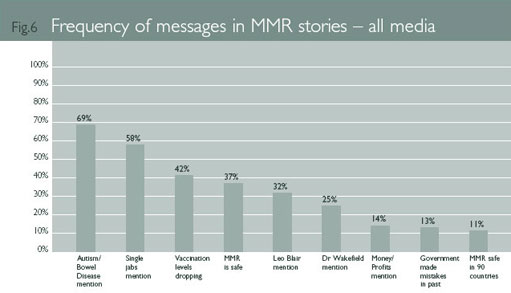

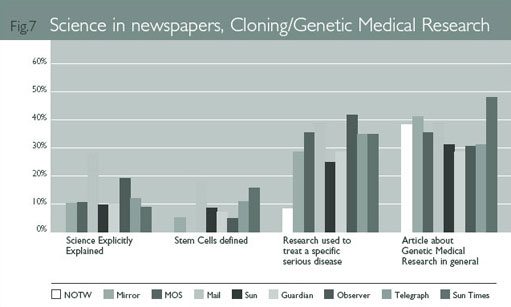

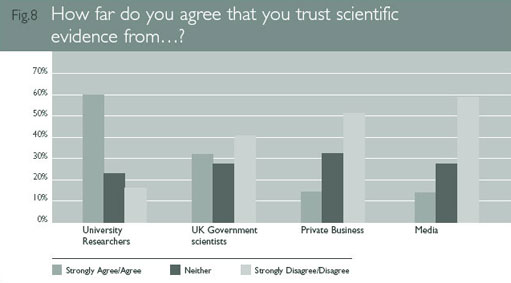

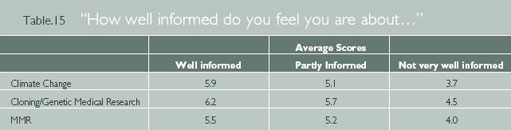

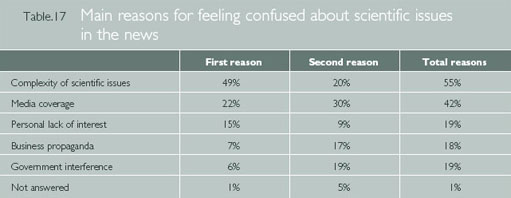

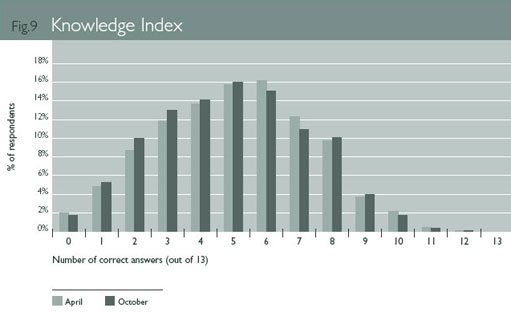

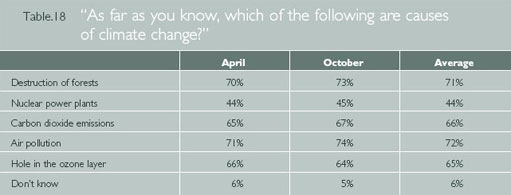

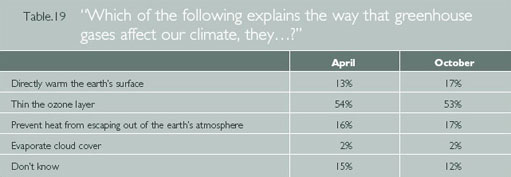

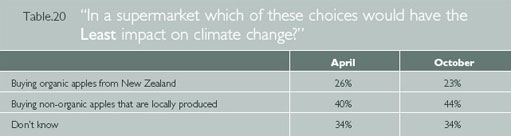

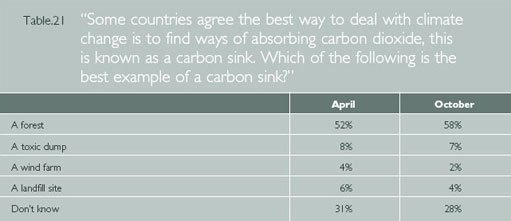

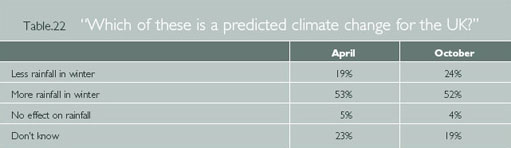

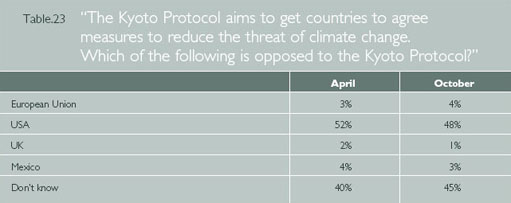

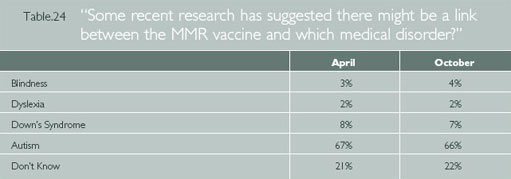

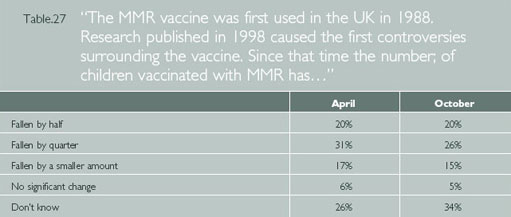

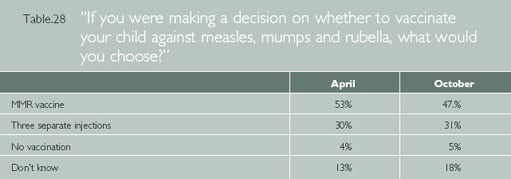

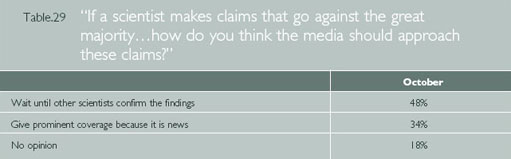

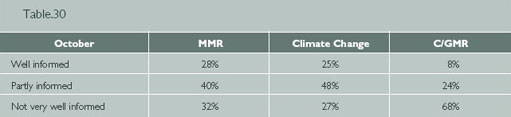

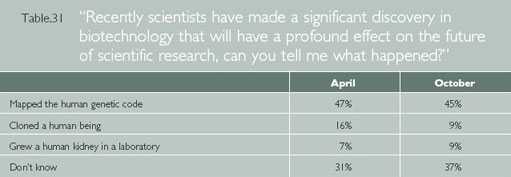

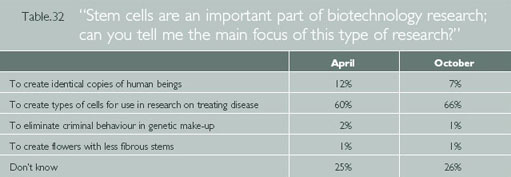

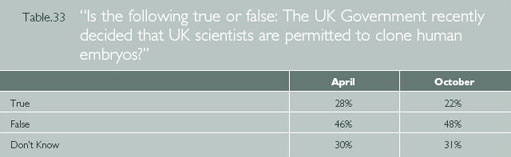

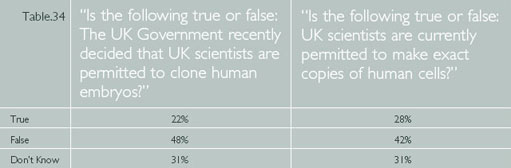

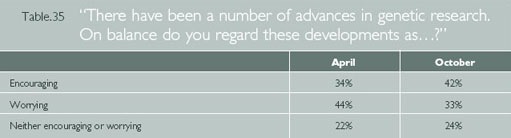

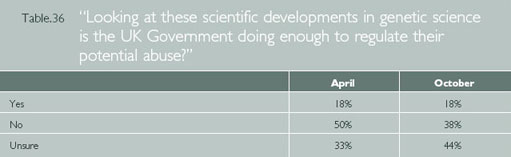

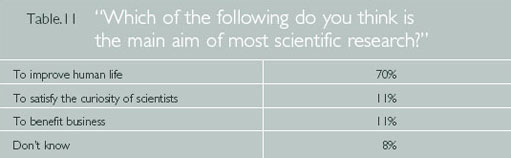

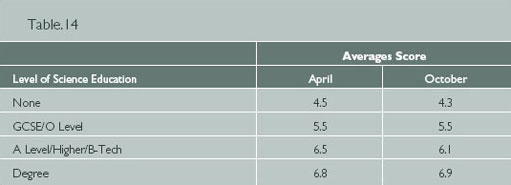

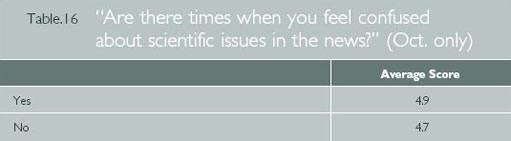

An important dimension to the social perception of risk is how the media report an issue. Researchers at the Cardiff University School of Journalism investigated media coverage of three scientific issues with social policy implications: climate change; cloning and genetic medical research; and the MMR vaccine. The study analysed the way the media covered the MMR controversy in 561 articles over a seven-month period. Then two nationally representative surveys were carried out in April and October 2002, with the stated aim of investigating how public understanding could be seen as reflecting the nature of the media coverage.

Reading 3

Click to view Reading 3: extracts from the ESRC report Towards a Better Map: Science, the Public and the Media. Take careful note of the way in which the information was obtained and how it is being interpreted. Note strengths and weaknesses of this type of content analysis and social science research.

Discussion

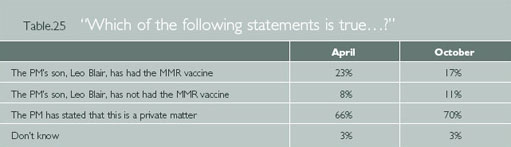

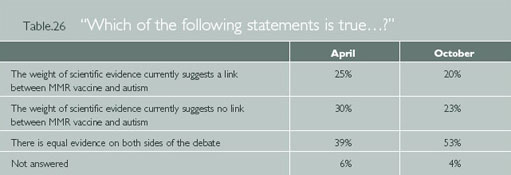

Although surveys of this type inevitably oversimplify the link between media coverage and public understanding of science, the results are useful for identifying certain trends. One of the most interesting findings of the research was that there was a mismatch between the information reported in the media and the public's impression of that coverage. An attempt by the media to provide ‘balance’, by covering both sides of the controversy, created the misleading impression that there was equal evidence on both sides of the debate (39% of respondents to the ESRC survey thought so in April 2002 rising to 53% by October), in spite of the majority of evidence being overwhelmingly in favour of the safety of MMR.

The reporting of the MMR controversy is an example of the ‘myth of balance’ in news coverage. Showing both sides of the story – often considered a hallmark of good reporting – does not guarantee objectivity or accuracy. This is not to say that such coverage somehow lacks legitimacy however. The processes by which news is produced and disseminated are very different to – and often incommensurable with – the processes by which scientific knowledge is generated. In a debate as complex as that about MMR, suffused as it is with politics, economics and ethics, there is no ‘right’ way to report the issue.

5.2 Blair's babe

The ESRC report demonstrated the high awareness amongst the public of the Leo Blair issue, in spite of it not being the most prominent aspect of the media coverage. In December 2001, during Prime Minister's Questions in the House of Commons, Tony Blair was asked whether his infant son had been immunised with MMR. Mr Blair declined to answer on the basis that it was a private family matter. The perception in the media was that if Leo had been immunised, Mr Blair would have been happy to say so. His wife, Cherie Blair, had been the subject of media reports highlighting her interest in New Age alternative medicine which contributed to the suspicion that Mr Blair was promoting MMR in public but opting out in private. The impact of this issue on immunisation levels is hard to measure in isolation but uptake certainly fell in the wake of the publicity (Fitzpatrick, 2004).

Activity 2 What do you think?

Politicians are often criticised for using their families for political gain (recall the now iconic image of John Gummer and his daughter reproduced in Reading 2), yet they are expected to act as suitable role models. Are politicians ethically obliged to follow their recommended policies, or is this indeed an undue invasion of privacy?

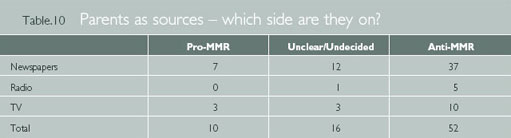

5.3 The expert patient

Shifting notions of expertise also feature in the ESRC report. While the medical establishment lined up to proclaim the safety of the MMR vaccine, the anti-MMR voices in the media were mainly provided by parents of autistic children. The unquestionable sincerity of these voices conferred upon them a high level of authority compared with the unemotional scientific evidence given by medical experts.

The continuum between lay expertise and scientific expertise is becoming increasingly blurred. Access to specialist data is no longer the preserve of an academic elite. The internet has meant that swathes of information are instantly available at many people's fingertips. As the volume of accessible information grows, so do the problems of evaluating that information. Doctors and health visitors provide a crucial link in this regard.

The medical profession is somewhat polarised on the concept of an ‘expert patient’. The legitimising of patient views (or, more accurately, parent views in the MMR debate) is seen as a backlash against ‘medical paternalism’. This is the idea that doctors patronise their patients by assuming that they know more about a condition than those living with it. Opponents of this view insist that lay people can never acquire the medical expertise necessary to discriminate between corroborated scientific evidence and rumour, conjecture and superstition. Proponents hold that patients' expertise does not undermine medical authority but helps doctors to understand a condition from a patient's perspective. A government-sponsored expert patient programme encourages patients with chronic illnesses to better self-manage their conditions, recognising that compliance with medication regimes is much more likely if patients have collaborated with their doctors in deciding on treatment (Shaw and Baker, 2004).

The expert-patient scenario described here, in which doctors and patients benefit from mutual expertise, does not ‘scale up’ to the type of media coverage in which patient or parent is often pitted against doctor or scientist. The implication in such coverage is that their expertises are equivalent and comparable. Although views from both lay and medical perspectives are valid in their own right, they are different in scope and focus. Once again, there is potential for tension between the scientific community and the public.

5.4 Telling tales

An aspect alluded to by the ESRC report is the importance of narrative: the way in which we organise events into intelligible stories. Media reports construct narratives, and we also impose our own narratives on the information we glean from a variety of sources. Narrative is a very powerful, often-unconscious human trait. Certain narratives, especially those involving conflict, are cross-cultural and deeply embedded in our psyches. They may have an appeal that transcends logic or conventional rationality. An appealing plot is one in which a sympathetic hero encounters a series of obstacles: everyone seems to be against the protagonist who is seen as a selfless crusader on behalf of common good. Andrew Wakefield easily fits this stereotype in popular imagination: the underdog ‘David’ pitted against the ‘Goliath’ of the medical and government establishment.

Activity 3

The factors that make for a ‘good story’ in the media often share elements of a good fictional plot. Can you identify other science-based news stories in which narrative appeal has potentially shaped public perceptions of an issue?

Discussion

Channel Five recognised the narrative potential in the MMR story and made it explicit: in December 2003 they screened a drama, written by Timothy Prager, called Hear the Silence. It starred Hugh Bonneville as Andrew Wakefield and Juliet Stevenson as the mother of an autistic child convinced of the link between the MMR vaccine and her son's condition. The drama, watched by 1.3 million people, stirred up a huge amount of controversy. Most of the coverage was negative, criticising the drama for being one-sided and for indulging in conspiracy theory. For example, Mark Lawson wrote in the Guardian (8 December 2003):

A series of distracted, sarcastic or conventional doctors representing conventional medicine are systematically shamed and humbled by Saint Mum and Saint Doctor. Scenes in which the Wakefields' phone is bugged and they receive threatening phone calls are casually dramatised, without any explanation of whether it's the drug companies or the NHS or the CIA that is being fingered for intimidation. If you walked into a doctor's surgery looking as lopsided as this drama, you would be sent for emergency orthopaedic surgery at once.

(Lawson, Guardian, 8 December 2003)

Channel Five, anticipating criticism, attempted to balance the anti-MMR message of the drama by following it with a prerecorded debate. Many leading MMR proponents declined invitations to appear on the programme in protest at Channel Five's ‘irresponsible’ dramatisation – ironically contributing ‘silence’ to what had hitherto been a very vocal debate in the media and the medical press. One commentator has this to say:

I can't claim to have been convinced by the heart-on-sleeve ‘heroic little doc versus the mighty medico-political-drug-company establishment’ thesis, but the film was a worthwhile and pungent contribution. Less so was the supposedly ‘balancing’ debate which followed. To stave off the controversy which the drama was bound to attract, Five assembled a panel to discuss the issues. And to emphasise the relative brilliance of drama, MMR: The Debate was ditchwater arid, with crummy sound, amateur camerawork and bad lighting. Perhaps the discrepancy can partly be ascribed to the fact that the film must have cost about a million quid, while the debate came free with a cornflake packet. Andrew Wakefield, Juliet Stephenson and the film's producer were pitched against GPs, biochemists – and a written statement from the Government. As I've said, I'm unconvinced by the film's thrust – but the Government's feeble disregard for the doubters' position can only feed the distrust.

(Courthauld, Observer on Sunday, 21 December 2003)

Whatever the doubts about the MMR message put across, Hear the Silence resonated strongly with parents of autistic children for highlighting the strain experienced by families coping with autism.

The narrative of Wakefield as a misunderstood genius has been reinforced by some of the images accompanying press coverage, most notably a photograph by Phil Hansen in the Sunday Times magazine in December 2003. Wakefield is depicted writing MMR: 1+1+1 ![]() 3 on a window – echoing memorable scenes from the film Beautiful Mind in which Russell Crowe, playing mathematician John Nash, covers his windows with mathematical equations.

3 on a window – echoing memorable scenes from the film Beautiful Mind in which Russell Crowe, playing mathematician John Nash, covers his windows with mathematical equations.

Activity 4 What do you think?

Was Channel Five irresponsible to dramatise the MMR–autism controversy, lending credibility to a scientifically discredited viewpoint? Or is it patronising to assume that the drama's stance will be slavishly adopted by a gullible public, incapable of separating fact from fiction?

6 Everyone's interests

So far we have seen that the MMR debate has been far from neutral, with collective and individual values playing a part in decision making – by scientists, policy makers and parents. One angle of the debate has been a preoccupation with conflicts of interest. With researchers increasingly reliant on funding from sources that have clear interests in the outcome, openness and transparency about who funds what research is deemed essential so that reviewers can take this into account when assessing whether a paper is suitably objective.

Events in the MMR debate took an important turn on 22 February 2004 when the Sunday Times reported that Wakefield had secured £55 000 from the Legal Aid Board in 1996, two months before the study reported in the 1998 Lancet paper commenced. The funding was to investigate the link between the MMR vaccine and autism in the cases of ten children with a view to establishing whether the parents would be able to sue for compensation. ‘Four, maybe five’ of the children were involved in the study reported in The Lancet. Although Wakefield continues to insist that this did not represent a conflict of interest, most of his co-authors and the editors of The Lancet thought otherwise. On 6 March 2004, a ‘partial retraction’ of the original paper was issued by ten of the thirteen authors. Whereas the findings on gastrointestinal problems associated with autism were allowed to stand, the interpretation of a possible link between autism and the MMR vaccine – although this was never made explicit in the paper – was deemed to have had ‘major implications for public health’ and the interpretation was formally retracted.

The Lancet requires authors to declare financial arrangements or personal relationships that could bias their work. The failure to declare the Legal Aid Board funding was the final straw for Lancet editor Richard Horton. Having spent six years defending his own and the journal's reputation from recriminations for publishing in the first place, the incident provided an opportunity for The Lancet to distance itself from what had become one of the most controversial papers ever published.

Reading 4

In a commentary accompanying the partial retraction of the 1998 paper, Richard Horton sets out the difficulties that accompany research of this type, and the problems with decisions about publication. Click to view Reading 4: Horton, R. ‘The lessons of MMR’, The Lancet, 363, pp. 747–49. Horton emphasises that there are ‘lessons to be learned’. List the lessons Horton outlines in this article, and compare it with your own list of what lessons you think should be learned from the MMR controversy. What is your position on the view that Horton was being opportunistic in using the conflict-of-interest issue to deflect criticism of his handling of the matter?

Peer review is often held up to be the criterion which distinguishes research that stands up to ‘scientific scrutiny’. It is a validation gateway through which scientific research must pass before it is admitted to the canon of reliable knowledge. Yet the process of peer review is highly subjective, relying on editors' and reviewers' judgements on the influence of funding sources on interpretation of results. It is widely recognised that few scientists are entirely disinterested in the results of their research, although these interests do not necessarily bias the outcome. However, by not declaring potential conflicts of interest, researchers leave themselves open to accusations of lack of integrity.

A second potential conflict of interest plays an important role in the MMR debate, and that is the funding general practitioners receive for reaching immunisation targets – in the region of £3000 per annum if 90% of the infants on their patient register complete the immunisation programme. This may have a negative effect on the perceived impartiality of the advice given to patients by GPs. Some practices were found to be removing unimmunised children from their registers in order to boost their percentage uptake.

Issues surrounding conflicts of interest serve to highlight the importance of trust. Parenting is largely a matter of instinct. Subjecting a child to a painful, invasive intervention, such as a vaccine, goes against instinct and relies on trust that the procedure is in the child's best interests. No matter how unproven the risk of contracting autism from MMR is, the decision to vaccinate remains a very real dilemma.

7 Concluding remarks

The MMR controversy is inherently complex and there are many additional facets of the debate that go beyond the scope of this course. The issues discussed here have sought to provide a social context for the MMR debate. It is unrealistic to expect scientific aspects to be separable from the myriad other factors that interact with science in a public context.

Decisions about MMR extend beyond science to emotional, ethical and political considerations. Stephen Pattison (2001) points out that ‘scientists must take care not to treat fear and reservation as ignorance and then try to destroy it with a blunt “rational” instrument’. I agree with him that to do so is to trivialise concerns of parents engendered by a lack of trust in official pronouncements of ‘safety’.

At the time of writing (August 2004), the MMR controversy is far from reaching closure. Wakefield is still a key player in the MMR debate, as Chief Medical Scientist for Visceral, a US-based charity which funds research into links between environmental factors and autism. Parents continue to agonise over the decision to allow their children to be immunised with the triple MMR jab. Sadly but inevitably, a small percentage of children will develop regressive autism, whether by coincidence or as a result of some as yet unknown cause.

The controversy surrounding the MMR vaccine has contributed to a lack of public confidence in combination vaccines, undermining a public health policy which has made a very real contribution to protection against infectious diseases. It is perhaps too simplistic to declare that Wakefield's original paper should never have been published. It is clearly undesirable for peer review to operate as a form of censorship: researchers should be allowed to raise concerns that contradict mainstream opinion without being ostracised. Yet the MMR debate has had a life of its own, extending far beyond the technical issues and scientific uncertainties. Could and should the controversy have been better managed? Should lay concerns be considered in conjunction with scientific evidence when making decisions about health policy? If you were faced with a decision on whether to immunise your child with the MMR vaccine, on what evidence would you base your decision?

My son was scheduled to have the MMR vaccine at the height of the flare up of the debate in 2001. My biochemical training and everything I'd read in the scientific research suggested that there was no evidence for a link between MMR and autism. So why was it still such a difficult decision? Parenting is not an inherently rational enterprise. After much soul searching, I did decide to have my children immunised with the MMR. For me, the risks to my children of suffering the ill effects of contracting the diseases themselves, or passing disease on to someone else, outweighed the risk that there might be something after all to the hypothesis that autism is linked to the MMR vaccine. But it was an anxious time – before and after the vaccination. I can empathise with parents who decide that the balance of risk is against MMR immunisation for their children.

Might future controversies be managed better if, for example, uncertainties and dissent are dealt with more even-handedly, lay understandings are acknowledged more explicitly, and the wider social context is articulated and explored?

8 Reading 1: The Lancet Paper

8.1 Reading 1: The Lancet Paper

Fitzpatrick, M. (2004) Chapter 8 ‘The Lancet Paper’ taken from MMR and Autism: What Parents Need to Know, London, Routledge. Copyright © 2004 Michael Fitzpatrick.

We identified associated gastrointestinal disease and developmental regression in a group of previously normal children, which was generally associated in time with possible environmental triggers.

(Wakefield et al., 1998, p. 637)

We did not prove a link between MMR vaccine and this syndrome [‘autistic enterocolitis’].

(Wakefield et al., 1998, p. 641)

Dr Wakefield's landmark paper, published in The Lancet on 28 February 1998, provided the missing link in the theory that MMR was responsible for the supposed ‘autism epidemic’. That link was ‘autistic enterocolitis’ – a novel and distinctive form of inflammatory bowel disease found in children with autism and other developmental disorders. Dr Wakefield was the ‘senior scientific investigator’ in the Royal Free research team and the paper's lead author. A dozen co-authors included paediatric gastroenterologists Simon Murch and Mike Thomson, who did the colonoscopies, child psychiatrist Mark Berelowitz, and Professor John Walker-Smith, who was the ‘senior clinical investigator’. Dr Wakefield and his colleagues believed they had made a discovery of historic significance; it was rumoured that some of them wondered aloud whether they might win a Nobel Prize or some similar recognition if their bold hypothesis was vindicated.

The paper was based on the investigation of 12 children, who were said to have been consecutively referred to Dr Wakefield's clinic at the Royal Free Hospital with a history of diarrhoea, abdominal pain, bloating, and food intolerance. The dozen included only one girl; in ten cases the diagnosis was autism or ‘autistic spectrum dis-order’; in two there was a suspicion of ‘post-viral encephalitis’; and in one the diagnosis was uncertain between autism and ‘disintegrative disorder’. Examination of the lining of the large and small intestine through a fibre-optic endoscope (ileo-colonoscopy) passed up the rectum (under sedation) revealed a distinctive pattern of inflammation (non-specific colitis) associated with enlarged lymph glands at the end of the small intestine (ileal lymphoid nodular hyper-plasia). Microscopic examination of biopsy specimens confirmed chronic inflammatory changes. Furthermore, the authors reported that the parents of eight of the children believed that their behavioural symptoms, characterised as ‘regression’, began shortly after the MMR immunisation (on average after 6.3 days). They suggested that, in these children, the measles virus (present in an attenuated form in the MMR vaccine) might have produced bowel inflammation, allowing toxic peptides to ‘leak’ into the bloodstream and hence pass to the brain, causing autism.

The authors conceded that they had not proved a link between MMR and ‘autistic enterocolitis’. However, they considered that the chronic inflammatory features they had identified in both the small and large bowels of these children ‘may be’ related to neuropsychi-atric dysfunction. The interpretation offered in the summary at the head of the report, as quoted above, was that the authors had ‘identified associated gastro-intestinal disease and developmental regression in a group of previously normal children, which was generally associated in time with possible environmental triggers’ (Wakefield et al 1998: 637). The only ‘environmental trigger’ identified in the report was MMR immunisation, which was linked by eight of the children's parents to the onset of their disturbed behaviour.

8.2 An acrimonious debate

Fitzpatrick, M. (2004) Chapter 8 ‘The Lancet Paper’ taken from MMR and Autism: What Parents Need to Know, London, Routledge. Copyright © 2004 Michael Fitzpatrick.

There were two unusual aspects to the publication of the Wakefield paper and both contributed to the subsequent furore. The first was that it was accompanied by a critical commentary by Robert Chen and Frank DeStefano, two American vaccine specialists (Chen, DeStefano 1998). The second was that it was launched at press conference at the Royal Free Hospital. Let us look at these in turn. As Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet, has indicated in his reflection on the ‘acrimonious debate’ that erupted following his decision to publish the Wakefield paper, he was well aware of its controversial character (Horton 2003: 207). The substance of Dr Wakefield's MMR-autism thesis had already been widely leaked and The Lancet's peer reviewers had raised concerns about the study's methods and interpretations, as well as about the dangers of undermining public confidence in immunisations. Dr Horton insisted that the paper was revised to clarify that its authors had no proof that MMR caused autism, following which it was published under the label of ‘early report’ to ‘highlight its preliminary nature’ (Horton 2003: 208). Furthermore, he commissioned two US vaccine experts, Robert Chen and Frank DeStefano to write ‘Vaccine adverse events: causal or coincidental?’ – a brief but devastating critique of the Wakefield paper published in the same issue of The Lancet (Chen, De Stefano 1998).

Chen and DeStefano first indicated the excellent safety record of MMR in hundreds of millions of people worldwide over three decades. They questioned whether the newly identified syndrome of autistic enterocolitis could be considered clinically distinctive: ‘no clear case-definition was presented, a necessary requirement of a true new clinical syndrome and an essential step for future research’ (Chen, DeStefano 1998: 612). They emphasised that the authors had not confirmed the presence of vaccine virus in the tissues of their patients. They suggested that ‘selection bias’ might have resulted from the referral of children to the clinic of ‘a group known to be specially interested in studying the relation of MMR vaccine with inflammatory bowel disease’ (Chen, DeStefano 1998: 612). They noted that it is usually difficult to date precisely the onset of a syndrome such as autism, and wondered whether ‘recall bias’ may have resulted from parents attempting to relate the onset of their child's problems to an unusual event such as a coincidental vaccine reaction. They also pointed out that, although Dr Wakefield and his colleagues postulated that MMR might lead to inflammatory bowel disease, which, in turn, might cause autism, in almost all the cases reported in their paper behavioural changes preceded bowel symptoms. The time course of these pathological processes was also curious: in one case the effect of MMR on behaviour was evident within 24 hours – faster than any known process of infection-induced vasculitis (the underlying pathology postulated as the cause of ‘autistic enterocolitis, a type of process that unfolds over several weeks).

In conclusion, Chen and DeStefano warned presciently that, if claims of adverse events resulting from vaccines were not properly substantiated, there was a danger that vaccine-safety concerns may ‘snowball into societal tragedies when the media and the public confuse association with causality and shun immunisation’ (Chen, DeStefano 1998: 612). Many of these themes were taken up and expanded in subsequent letters to The Lancet.

In retrospect, Dr Horton conceded that the publication of Dr Wakefield's paper in The Lancet gave it ‘more credibility than it deserved as evidence of a link between the MMR vaccine and the new syndrome’ (Horton 2003: 209). Yet, while he defended his decision to publish the paper, he unreservedly admitted to ‘a failure to manage the media reaction’ – a failure that started with the now notorious Royal Free press conference.

The press conference was an extraordinary event. Journalists were treated to a special introductory video prepared by the Royal Free press office and the Dean of the Medical School, Professor Arie Zuckerman, himself a vaccine specialist, presided over the conference. (Professor Walker-Smith refused to attend, indicating that he disapproved of medical research being debated prematurely in the mass media. He has recalled that the only enthusiasm for the conference came from Dr Wakefield and his staunch ally Professor Roy Pounder, senior adult gastroenterologist at the hospital [Walker-Smith 2003: 241].)

Dr Wakefield seized the next day's headlines with his sensational recommendation that parents should reject the MMR immunisation and give their children each of the three components separately, 12 months apart (The Times, 27 February 1998, Daily Telegraph, 27 February 1998). This recommendation was not included in the Lancet paper and is in no way supported by it. Such a programme of vaccination has not been introduced anywhere in the world and there is no evidence to justify any particular interval between vaccinations. It was immediately repudiated by Professor Zuckerman and by the paediatricians in the Wakefield team. Dr Simon Murch, Dr Mike Thomson and Professor Walker-Smith subsequently wrote to The Lancet to disassociate themselves from Dr Wakefield's call for separate vaccines (Murch et al 1998). Not a single member of the team publicly endorsed Dr Wakefield's anti-MMR stand. Yet, as the press conference broke up in rancour, the campaign against MMR received its biggest boost so far.

Five years later Richard Horton was still smarting from the ‘vituperative attack and personal rebuke’ he experienced as a result of his decision to publish the Wakefield paper (Horton 2003: 213). Many critics complained that The Lancet's process of peer review should have exposed the weaknesses of the paper and prevented its publication. Dr Horton insists that the role of peer review is not to judge the validity of a piece of research – that can only be verified by other scientists – but to comment on the importance of the issue under investigation and on the design and execution of the study (Horton 2003: 213). He decided to publish Wakefield's paper, not because he believed it to be true, but because it raised an important question that required urgent verification. Dr Horton has argued the important principle that medical journals must uphold free expression in scientific debate even if this creates problems for public health. He maintains that to have refused to publish Wakefield would have been an act of censorship. But, as Chen and DeStefano and many others have pointed out, there were basic errors in design, execution, analysis and interpretation in the Wakefield paper. Dr Horton indicates elsewhere that, every year, The Lancet publishes 500 out of 10,000 papers that are submitted: this is not censorship but editorial judgement (Horton 2003: 307). Indeed, when Dr Wakefield submitted his follow-up paper, including a further 48 cases, Dr Horton exercised this discretion and rejected it (it was finally published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology; Wakefield et al 2000).

8.3 MMR and the Medical Research Council

Fitzpatrick, M. (2004) Chapter 8 ‘The Lancet Paper’ taken from MMR and Autism: What Parents Need to Know, London, Routledge. Copyright © 2004 Michael Fitzpatrick.

Although the Royal Free press conference projected the MMR-autism debate onto the national stage, and Dr Wakefield gained a growing status among anti-immunisation campaigners and parents of autistic children, he made little headway in convincing his medical and scientific colleagues of his case. In March 1998, at the request of Sir Kenneth Caiman, Chief Medical Officer, the Medical Research Council (MRC) convened an ad hoc group of 37 experts, drawn from the spheres of virology, gastroenterology, epidemiology, immunology, paediatrics and child psychiatry, to review the associations suggested by the Royal Free team between measles virus and MMR on the one hand, and between inflammatory bowel disease and autism on the other (MRC 1998). The group's meeting was chaired by the pathologist Professor Sir John Pattison (a veteran of the mad cow crisis); Dr Wakefield and epidemiologist Scott Montgomery (one of the Royal Free team) attended the meeting to present and discuss their case.

The group first considered the laboratory evidence produced by the Royal Free group for the hypothesis that measles virus caused inflammatory bowel disease and noted that ‘the most sensitive molecular genetic techniques were negative in the hands of all groups’ (MRC 1998: 2). They emphasised that further studies ‘must involve independent laboratories testing the same specimens, using full controls and a range of techniques with agreed experimental protocols’ (MRC 1998: 2). When considering the epidemiological evidence claimed to link viral infections and inflammatory bowel disease, the group found no correlation between measles or mumps infection alone and Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. The experts agreed that there was some correlation between the occurrence of measles and mumps infection within the same year and the later incidence of inflammatory bowel disease. However, they considered existing studies limited and recommended further examination by independent groups.

On autism, the group considered the Lancet paper and emphasised the point that autism commonly becomes apparent in the second year of life – at around the time children receive MMR. However, the group insisted, ‘such coincidence does not imply a causal link’. They pointed out that, whatever the trends in the incidence of autism, they bore no relationship to the Introduction of MMR. They considered that the proposed ‘leaky bowel’/opioid excess mechanism was ‘biologically implausible’ (MRC 1998: 3). They further pointed out that the supposedly distinctive pattern of ‘lymphoid nodular hyperplasia’ identified by the Royal Free group was a common and benign condition in children. Finally, it was argued that the findings of abnormally low levels of some immunoglobulins (IgA) in four out of the twelve children was a simple error resulting from the use of adult normal ranges (when using appropriate paediatric ranges, only one child had a low IgA level) (Richmond, Goldblatt 1998).

After a day-long meeting the experts concluded that there was no current evidence linking MMR and autism. They thought that ‘it would be surprising if the link had not been noted in other countries with good diagnostic facilities for autism where MMR has been widely given for many years’ and suggested that ‘further research on an international basis would settle this matter’ (MRC 1998: 3). The expert group advised the Chief Medical Officer that there was no reason for a change in current MMR vaccination policy, as had been recommended by Dr Wakefield. However, they proposed more research on both inflammatory bowel disease and autism. These Conclusions were sent in summary form to every doctor in the country in a letter from the Chief Medical Officer on 27 March (Caiman 1998).

Dr Wakefield later complained that he felt he had been ‘set up’ at this meeting (Mills 2002: 17). He claimed that the 37 experts had all been ‘picked by the government’ and that he and Dr Montgomery had had to face them ‘alone’. He felt that a nine-hour meeting fell short of the detailed scrutiny he had hoped for.

Following the March 1998 meeting, the MRC set up an expert subgroup to steer and monitor research in inflammatory bowel disease and autism. This subgroup included leading figures in the relevant disciplines and it invited other specialists to attend particular meetings: these included Dr Wakefield, and his co-authors Professor John Walker-Smith and Dr Simon Murch. In its report in April 2000, the subgroup noted further evidence from the Royal Free group of ‘a classic pan-colitis associated with severe constipation and immune dysregulation in a group of children with developmental disorders’ (MRC 2000, Wakefield et al 2000).

This study compared a series of 60 ‘consecutive’ cases of ‘autistic enterocolitis’ (including the orginal 12), with a control group of 37 developmentally normal children undergoing ileo-colonscopy. Given the controversy still raging around the Lancet paper, it was curious that the new study included no information about MMR or any other immunisation history. The study confirmed ‘an endoscopically and histologically consistent pattern of ileo-colonic pathology’ in ‘a cohort of children with developmental disorders’ (Wakefield et al 2000: 2294). It also recorded results of investigations suggesting minor immunological abnormalities. The authors described a subtle ‘new variant’ inflammatory bowel disease, lacking the specific features of either Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis. They again drew attention to the association of this pattern of bowel disease with ‘a developmental disorder that was associated with a clear history of regression’ – a loss of skills after a year or more of normal development. They concluded that ‘this syndrome [autistic enterocolitis] may reflect a subset of children with developmental disorders with distinct etiological and clinical features’ (Wakefield et al 2000: 2294).

This study was open to the same charges of selection bias as the Lancet paper. It was also criticised on the grounds that the control group was not properly matched for age. Apart from providing a fuller picture of the supposed new syndrome of ‘autistic enterocolitis’, it added little to the continuing MMR-autism controversy. The MRC report concluded that ‘the case for “autistic enterocolitis” had not been proven’ (MRC 2000: 4). It commented that the Royal Free studies had been performed in a ‘self-selected group of patients and the histological finding of ileal lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia may have been secondary to severe constipation’ (MRC 2000: 4).

The subgroup concluded that, in the 18-month period following Dr Wakefield's Lancet paper, ‘there had been no new evidence to suggest a causal link between MMR and inflammatory bowel disease/autism’ (MRC 2000: 5). It conceded that much remained unknown about these conditions and that MRC support for research in these areas, particularly inflammatory bowel disease, was weak. It made a series of specific recommendations for future research.

8.4 Testing the MMR-autism hypothesis

Fitzpatrick, M. (2004) Chapter 8 ‘The Lancet Paper’ taken from MMR and Autism: What Parents Need to Know, London, Routledge. Copyright © 2004 Michael Fitzpatrick.

In the concluding ‘discussion’ section of their Lancet paper, Dr Wakefield and colleagues suggested that further investigations were needed to examine the syndrome of ‘autistic enterocolitis’ and ‘its possible relation’ to MMR (Wakefield et 1998: 641). They indicated two directions for further research. First, the authors observed that if there were a causal link between MMR vaccine and this syndrome ‘a rising incidence might be anticipated after the introduction of this vaccine in the UK in 1988’. They considered that published evidence was inadequate to answer this question, inviting further epidemio-logical research to clarify it. Second, they reported that ‘virological studies’ (presumably those later reported by the team headed by Professor John O'Leary in Dublin, Ireland) were ‘underway’. Let us now examine the outcome of attempts to substantiate the MMR-autism hypothesis through researches in these areas.

In its responsibility for vaccine safety, the Medicines Control Agency commissioned an epidemiological study to investigate the question of whether there was an increase in cases of autism in Britain following the introduction of MMR. Dr Wakefield's challenge to analyse any rise in incidence was taken up by Professor Brent Taylor, community paediatrician at the Royal Free Hospital, and a team including vaccine specialist Dr Elizabeth Miller and Open University statistician Dr Paddy Farrington. Their results were published in The Lancet in June 1999 (Taylor et al 1999a).

They identified all known children with an autistic spectrum disorder born between 1979 and 1998 in eight North Thames health districts 498 children in all – and studied their medical and vaccination records. They found that:

-

although the number of cases of autism had increased steadily since 1979, there was no sudden ‘step-up’ or change in the trend line after the Introduction of MMR in 1988;

-

there was no difference in age at diagnosis between the cases vaccinated before 18 months of age, after 18 months of age, and those never vaccinated;

-

there was no clustering of developmental regression in the months after vaccination.

They concluded that ‘our analyses do not support a causal association between MMR vaccine and autism’ (Taylor et al 1999a: 2026).

The authors themselves acknowledged two limitations of their study. They could not verify the diagnoses of autism in all cases and they may have missed some cases. They relied on clinical notes of variable quality and many did not contain systematic or regularly updated information, which would have allowed independent validation of diagnosis. Despite making ‘substantial efforts’ to identify all cases, they may have missed some children who were not known to local health or education authorities. However, it is unlikely that these factors significantly affected the overall results.

In a letter to The Lancet, Dr Wakefield criticised the Taylor study on three grounds (Wakefield 1999). He claimed that the statistical methodology used (‘case-series’) was inappropriate to detect temporal associations between vaccination and conditions, such as autism, characterised by an insidious onset and delay in diagnosis. On the contrary, the authors replied, this method was particularly suitable for this sort of study, which has a good record of revealing rare adverse effects (Taylor et al 1999b). Dr Wakefield's second objection focused on the authors’ judgement that one finding that of a marginally significant raised incidence of parental concern between 0 and 5 months after MMR – was a statistical artefact. The authors claimed that one such finding (out of 14) might have been expected by chance, and that it could be explained by ‘the combined effect of approximate recording of parental concern at 18 months and a peak in MMR vaccinations at 13 months’. Finally, Dr Wakefield made the accusation that the authors had ‘failed to declare’ the fact that some of the children in the study may have received MMR as a result of a catch-up campaign. The authors’ rebuttal was that these children had been identified and that in all cases in which the age of first parental concern was recorded, it preceded vaccination.

If epidemiological studies failed to support the MMR-autism hypothesis, what about the virological studies? During 2002 two papers based on studies of intestinal biopsies on Dr Wakefield's ‘autistic enterocolitis’ patients by a team lead by Professor John O'Leary in Dublin were published.

In the first paper, published in February, the researchers claimed to have identified fragments of the measles virus in intestinal tissues of 75 out of 91 children with inflammatory bowel disease and developmental disorder (Uhlmann et al 2002). However, this study did not indicate whether the children had had measles or MMR. The authors did not indicate whether they had found whole measles virus, whether of wild or vaccine strain, or any other viruses, such as mumps and rubella. Many commentators wondered whether inadvertent sample contamination or some other technical error with the notoriously difficult reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assays might explain these results (Afzal et al 2003). The study was also criticised on the grounds that the controls were not matched for age or time since vaccination. Others observed that, even if these findings were confirmed and replicated, the presence of measles virus fragments in the gut would not prove that they caused either inflammatory bowel disease or autism.

In response to the controversy generated by his paper, Professor O'Leary issued a statement insisting that he had ‘not set out to investigate the role of MMR in the development of either bowel disease or developmental disorder, and no conclusions about such a role could, or should be, drawn from our findings’ (O'Leary 2002a).

In a presentation in June 2002 to a US congressional committee Dr Wakefield claimed that a new study, due to be published by Professor O'Leary, had confirmed that the measles virus present ‘in the diseased intestinal tissues of children with regressive autism’ was indeed derived from the MMR vaccine (Wakefield 2002a). For Dr Wakefield, these studies constituted ‘a key piece of evidence in the examination of the relationship between MMR vaccine and regressive autism’. Professor O'Leary, however, promptly rejected Dr Wakefield's interpretation of his work, insisting that it ‘in no way establishes any link between the MMR vaccine and autism’. (O'Leary 2002b). Indeed, he strongly recommended that parents should give their children MMR1.

An abstract (summary) of the new O'Leary study was duly presented at the annual meeting of the Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland in Dublin in July 2002. This was a pilot study designed to discover whether the measles virus RNA found in the guts of children in the earlier study originated in wild measles or from immunisation. The paper described a technique for discriminating between two closely related genome sequences, which the authors claimed could distinguish between wild and vaccine strain measles (by identifying a single nucleotide at position 7901 of the genetic code of the wild measles virus). They found vaccine-strain measles virus in the gut biopsies of 12 children with inflammatory bowel disease and development disorder (and confirmed wild measles strain in brain specimens of three patients with SSPE – a rare complication of measles). They concluded that ‘this pilot study corroborates our earlier findings of an association between the presence of measles virus and gut abnormalities in children with developmental disorder, and indicates the origins of the virus to be vaccine strain’ (Shiels et al 2002).

However, an immediate response to this study from the WHO collaborating centre for measles in the UK challenged the validity of the technique used by O'Leary's team. This indicated that the method used was not able to distinguish between wild and vaccine strains (it could result in several wild strains being incorrectly classified as vaccine strains). ‘Consequently’, it concluded, ‘the technique described does not reliably discriminate between wild and vaccine measles virus’ (Brown et al 2002). When presented with this information at the US congressional hearings on autism, Dr Wakefield accepted that if this method could not reliably make distinguish the two different forms of measles, then the Conclusion drawn by the paper was not justified. The first piece of evidence promising some support to the hypothesis advanced by Dr Wakefield in 1998 was thus discredited even before publication.

1 It is interesting to note that Professor O'Leary's repudiation of the claims, made on his behalf by Dr Wakefield and his supporters, has never been acknowledged by the anti-MMR campaigners, who continue to cite O'Leary's research in support of the MMR-autism thesis, in explicit defiance of his statements to the contrary.

8.5 MMR safety

Fitzpatrick, M. (2004) Chapter 8 ‘The Lancet Paper’ taken from MMR and Autism: What Parents Need to Know, London, Routledge. Copyright © 2004 Michael Fitzpatrick.

In January 2001 Dr Wakefield adopted a radically different tack in the campaign against MMR. He now turned to the field of public health and vaccination policy, questioning whether appropriate safety procedures had been followed when MMR was introduced into Britain in the late 1980s. In a paper written with his Royal Free colleague, epidemiologist Scott Montgomery, Dr Wakefield claimed that the trials carried out on MMR before it was licensed in Britain involved monitoring children for side effects for only 28 days (Wakefield, Montgomery 2000). They also claimed that the authorities had not taken account of the problems of ‘viral interference’ arising from using the combined MMR vaccine and that early studies had missed or ignored evidence of gastro-intestinal side effects of MMR.

Entitled ‘MMR vaccine: through a glass, darkly’2 the Wakefield and Montgomery paper provoked a storm of controversy.

It was published in the Adverse Drug Reactions and Toxicological Reviews, a highly specialist (and now defunct) journal with a regular readership estimated at around 300. The editors of this journal, anticipating a critical response to the article, published it together with the comments of four reviewers. (Critics subsequently pointed out that, although the reviewers were distinguished in their own fields, they did not include a vaccine specialist.) The most significant comment came from Dr Peter Fletcher, a former head of the Committee on Safety of Medicines, who substantially endorsed the case made by Wakefield and Montgomery and concluded with the damning judgement that ‘the granting of a produce licence [for MMR] was premature’ (Fletcher 2001: 289). In the subsequent discussion, another supporter of the anti-MMR campaign emerged: Dr Stephen Dealler, consultant microbiologist at Burnley General Hospital in Lancashire (Dealler 2001). A veteran of the BSE/CJD controversy, in which he emerged as a protege of Professor Richard Lacey (whose maverick reputation appeared to be enhanced when the nightmare scenario he had long predicted came, at least in part, to pass), Dr Dealler had now become a supporter of Dr Wakefield's theory of autism (see Fitzpatrick 1998: 45–8). He had already published a comprehensive endorsement of unorthodox biomedical approaches to autism on the Internet (Dealler 1999).

Recognising that his most recent paper might not otherwise attract public attention, Dr Wakefield launched the article at a press conference and released copies of the paper to the mainstream media before either public health authorities or doctors involved in giving vaccinations had a chance to read it. Another stormy press conference guaranteed a blaze of publicity (Abbasi 2001).

The Wakefield/Montgomery paper prompted forceful rebuttals from vaccine authorities. On behalf of the Medicines Control Agency, Arlett and Bryan insisted that the MMR trials had followed up children for between six and nine weeks (and, in some studies, for longer) (Arlett, Bryan 2001). They accused Wakefield and Montgomery of errors of statistics and interpretation of key surveys, and claimed that they had missed or ignored other important studies. A scathing review from the Public Health Laboratory Service (now the Health Protection Agency) concluded that ‘overall, we find this paper lacking in a coherent scientific rationale, selective in the reporting and interpretation of other work and statistically invalid’ (Miller, Andrews 2001). Paediatric vaccine specialists dismissed the concerns raised by Wakefield and Montgomery as ‘idiosyncratic’ and questioned the authors' tactics in presenting their paper to the popular press before most clinicians had a chance to read it in a peer-reviewed journal (Elliman, Bedford, 2001).

Two distinct issues were confused in the discussion of ‘interference’ (Arlett, Bryan 2001, Wakefield, Montgomery 2001). One is the question of whether there is a higher incidence of adverse reactions with the combined vaccine, compared with vaccines given separately. Contrary to Dr Wakefield's claims, the consensus emerging from a number of studies is that there is not (Halsey 2001). For the MCA, Arlett and Bryan insisted that there was no convincing evidence of either chronic gastro-intestinal problems or autism resulting from MMR (Arlett, Bryan 2001). The second is the question of ‘immuno-logical interference’: does giving three antigens together lead to a diminished antibody response to each one? According to the review by the American Academy of Pediatrics, ‘although early studies showed the potential for some interference between these vaccine viruses as indicated by reduction in the mean antibody response to one or more of the components in the combined vaccines, adjusting the titres of the vaccine viruses resulted in similar responses for the combined and separate administration of these vaccines’ (Halsey 2001: 25). Arlett and Bryan pointed out that, in 30 studies of the combined MMR vaccine before its Introduction in Britain, no problems of interference had been identified. Furthermore, the effectiveness of post-licensing surveillance had been confirmed by its success in identifying, as a rare adverse reaction, ITP (idiopathic thrombo-cytopenic purpura – a rash associated with a blood abnormality, which usually resolves spontaneously) at a rate of one in 24,000 cases (Miller 2001).

In the subsequent discussion about the safety of MMR a number of issues arose (although none shed much light on the MMR-autism hypothesis). One set of concerns – promoted at first by the wider anti-immunisation movement – focused on the withdrawal in Britain in 1992 of two brands of MMR that used a mumps component derived from the Urabe strain of the virus. In 1988, before the Introduction of MMR in Britain, a study in Canada and the UK reported the occurrence of aseptic meningitis following immunisation with the Urabe strain mumps vaccine, at a rate of between one in 100,000 to one in 250,000. Given that this rate of meningitis was much lower than that occurring with natural mumps (which MMR had been shown to prevent) it was preferable to proceed with the Introduction of MMR. Furthermore, it was not, at that time, clear that any alternative vaccine was safer. However, although passive surveillance procedures showed a very low risk, a more intensive study in 1992 in the Nottingham area revealed a higher incidence of aseptic meningitis at a rate of one in 3,000 – following MMR (Miller et al 1993). Accordingly, the vaccine authorities decided to switch to using only brands of MMR containing the Jeryl Lynn strain of mumps (which had not been linked to cases of meningitis). In response to continuing claims of government perfidy in introducing MMR including Urabe (on the grounds that it was known to cause aseptic meningitis in rare cases), it has been pointed out that, if Jeryl Lynn had not been available, it would still have been preferable to carry on with MMR include Urabe as the benefit from reducing the risk of mumps far exceeded the risk of vaccine-related meningitis.

Another controversy arose from official attempts to promote studies of MMR safety in general as evidence against claims that it caused autism. The most popular study in this regard comes from Finland – a country that introduced a two-dose MMR programme in 1982 and now claims to have virtually eradicated these three diseases. Long-term population-based passive surveillance studies found that no cases of developmental regression had been reported as resulting from MMR in 1.8 million children (Peltola et al 1998, Patja et al 2000). It is true, however, that because people in Finland had no reason to suspect that MMR might be associated with autism, they would be unlikely to report it as an adverse reaction. Dr Fletcher, among many others, was critical of the government's use of such ‘negative studies as absolute evidence of safety’. Nevertheless, the large-scale, long-term, comprehensive and prospective character of these studies make them strong evidence for the safety of MMR in general (Bandolier 2002).