Gene testing

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 27 April 2024, 2:32 AM

Gene testing

Introduction

This course looks at three different uses of genetic testing: pre-natal diagnosis, childhood testing and adult testing. Such tests provide genetic information in the form of a predictive diagnosis, and as such are described as predictive tests. Pre-natal diagnosis uses techniques such as amniocentesis to test fetuses in the womb. For example, it is commonly offered to women over 35 to test for Down's syndrome. Childhood testing involves testing children for genetic diseases that may not become a problem until they grow up, and adult testing is aimed at people at risk of late-onset disorders, which do not appear until middle age. In addition, we address some of the issues involved in carrier testing, another predictive test. This involves the testing of people from families with a history of genetic disease, to find out who carries the gene, and who therefore might pass the disease onto their children even though they themselves are unaffected. Here the aim is to enable couples to make informed choices about whether or not to have children, and if so whether they might have a genetic disease.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 1 study in Science.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand something of the role of a genetic counsellor and its non-directiveness

understand the difference between pre-natal diagnosis, childhood testing and adult testing and give some examples of diseases that may be tested for

understand the ethical and moral difficulties involved in making decisions on whether or not to carry out such tests.

1 Genetic testing

1.1 What is genetic testing?

When most people encounter genetic testing today, it is usually in a medical context. We may be referred by our GPs to a regional genetics unit, or we may approach our doctors, asking for genetic tests because we suspect something about our family history. In this course we look at the issues and problems facing individuals and families when confronted with genetic testing.

The technologies that make genetic testing possible range from chemical tests for gene products in the blood, through examining chromosomes from whole cells, to identification of the presence or absence of specific, defined DNA sequences, such as the presence of mutations within a gene sequence. The last of these is becoming much more common in the wake of the Human Genome Project. The technical details of particular tests are changing fast and they are becoming much more accurate. But the important point is that it is possible to test for more genes, and more variants of those genes, using very small samples of material. For an adult, a cheek scraping these days provides ample cells for most DNA testing.

At this stage, we should distinguish testing from genetic screening. Genetic testing is used with individuals who, because of their family history think they are at risk of carrying the gene for a particular genetic disease. Screening covers wide-scale testing of populations, to discover who may be at risk of genetic disease.

All these different kinds of test can bring benefits. But all three, i.e. pre-natal diagnosis, childhood testing and adult testing, have also been noted as requiring careful management because of ethical problems that can arise from the kind of information they provide. We are confronted with moral choices here, for example, who gets that information and under what circumstances, what they do with it, and who decides what to do with it, are all important issues. Even finding out what people would like to know is not necessarily straightforward. (Is telling someone they can have a test for Huntington's disease, say, the same as telling them they may be at risk of the disease?) Here we are not primarily concerned with the technologies for testing, but with the ethical context within which testing takes place; a context framed by issues such as informed consent, individual decision-making and confidentiality of genetic information. Before looking at any of these questions in detail, though, a few words about the context in which they most often occur – genetic counselling.

1.1.1 Genetic counselling

In the UK and many other countries, genetic testing is provided by the National Health Service (NHS) or its equivalent, only after patients have undergone genetic counselling. This is defined as the provision of information and advice about inherited disorders, and includes helping people to:

Understand medical facts;

Appreciate the way in which inheritance contributes to the disease in question;

Understand the options for dealing with the disorder;

Choose the course of action with which they feel most comfortable – or least uncomfortable.

The advice-giver may be a doctor, a specialist genetic counsellor or, perhaps, a nurse with special training in genetics.

The core value of genetic counselling is often taken to be non-directiveness; it is not the counsellor's job to tell a patient what to do, but simply to help them to make an informed decision. Thus genetic counselling is ‘not about making wise decisions, but about making decisions wisely’. Counsellors should not even advise people whether to take a test or not, nor should they recommend a particular course of action should the patient opt for testing. Despite the long tradition of non-directiveness in genetic counselling in the USA and Europe, there are still debates about it in a medical setting. One problem is how to assess the success of a counselling service. How can one measure ‘effective communication’, and ‘good decision-making’? For example, should pre-natal diagnosis be assessed in terms of the number of tests carried out and pregnancies terminated (which is an option if a pre-natal test indicates an affected fetus)? This would provide administrators with useful numbers, but has been criticized as forcing counsellors to see success in terms of only one output — and hence encouraging directiveness. Simply providing genetic counselling and the option of pre-natal testing might make some individuals feel that they have to have a termination if the pre-natal test indicates problems.

Another aspect of genetic counselling is the provision of carrier testing for families whose history makes them suspect that they may have a genetic disorder. This means identifying those individuals who, although not suffering from the recessive disorder, do carry one version of the faulty gene and could pass it onto their children. Although carrier testing does not involve the emotional challenges of telling patients that they, or their child, have a genetic disorder, it does involve issues such as risk to future children, and whether partners should be tested to see if they too are carriers.

The point about this brief discussion of genetic counselling has not been to provide clear-cut answers, but to show that even in the case of a practice that has been developed for decades, there are still a large number of issues that are hard to settle. Thus we should not be surprised to find that when we look at more recent developments in genetic technologies — such as testing for multifactorial diseases — clear-cut answers and easy predictions about how people behave and what services to offer are also in short supply.

SAQ 1

What skills do you think a genetic counsellor has to develop?

Answer

Genetic knowledge, empathy, communication skills, and patience are all likely to be valuable.

1.1.2 Pre-natal diagnosis

The type of genetic testing that the majority of us are most likely to come across is still pre-natal diagnosis (PND). This involves testing a fetus during pregnancy, to see whether it is likely to suffer from a number of different disorders — some genetic, some not. While recent developments allow tests for certain multifactorial genetic diseases (such as spina bifida), pre-natal diagnosis has been available since the 1960s to test for Down's syndrome.

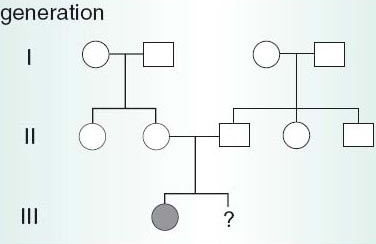

Most cases of Down's syndrome are the result of a new mutation arising in the gamete-producing cells. This contrasts with childhood diseases, such as cystic fibrosis (CF), which result from the fetus inheriting two recessive mutations because the parents are carriers. Here pre-natal diagnosis has removed much of the uncertainty about the risks of genetic diseases. In a family who know that both parents are carriers of CF, either because they already have a CF child (Figure 1) or as a result of carrier testing, PND allows the conversion of a probable risk of the disease affecting an unborn child to nearer a certainty that it will or will not be affected.

Figure 1

SAQ 2

Examine figure 1 above. Will the second child of the family depicted in the chart be affected with cystic fibrosis?

Answer

For an individual to suffer from cystic fibrosis they must inherit two copies of the cystic fibrosis gene, one from each parent. The parents must therefore be carriers (and they each would have inherited one copy of the cystic fibrosis gene from one of their parents, who would also have been a carrier).

The chance of having a child with cystic fibrosis is 1 in 4 for the second child and for any subsequent children, regardless as to whether or not the first child has cystic fibrosis. This is because it is based on the same two events, namely:

equal numbers of cystic fibrosis and normal gametes are produced;

male and female gametes combine at random during fertilization.

Pre-natal testing might then change the probability from 1 in 4 to near certainty that the fetus is or is not affected. However, pre-natal diagnosis cannot be used to rule out all possible birth defects, or all genetic disorders, because suitable tests do not yet exist to detect them. Nor is it foolproof even for those diseases that it can generally detect, such as CF.

Box 1 outlines the techniques for pre-natal diagnosis of fetal abnormalities early in pregnancy.

As more pre-natal testing is performed, we may see an increase in abortions since there may be no treatment for the particular disease detected. Yet this is obviously a difficult decision to make, not only in terms of the very public debates that surround abortion, but also with regard to the difficult private decisions that women (and their partners) face in these circumstances.

Box 1 Techniques for pre-natal diagnosis of fetal abnormalities

There are a number of techniques available for pre-natal diagnosis, and these are listed in Table 1 along with the abnormalities or diseases they can be used to detect.

| Technique | Abnormality/disease detected |

|---|---|

| maternal serum screening: determination of fetal protein levels | spina bifida |

| ultrasonography | organ abnormalities of nervous system, kidneys, heart, gut and limbs |

| fetoscopy | organ and limb abnormalities, skin disorders, blood disorders |

| amniocentesis: | |

| karyotype analysis | Down's syndrome |

| DNA studies | many genetic disorders |

| determination of fetal protein levels | spina bifida |

| chorionic villi sampling | genetic disorders (e.g. muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis, Huntington's disease) |

Maternal serum screening tests the mother's blood for the presence of proteins produced by the fetus; both it and ultrasonography are non-invasive with no known risk to the mother or fetus. Fetoscopy has the advantage that the fetus can be visualized directly by inserting a very fine optical telescope (fetoscope) through the abdominal wall into the uterine cavity. Amniocentesis involves the removal of a small amount of amniotic fluid, which bathes the developing fetus and contains fetal cells. The fluid can be analysed for its protein content, which may be abnormal in spina bifida, or chromosomes can be counted or the DNA analysed for certain genetic abnormalities. Another common approach is chorionic villi sampling, which is the removal of cells from the edge of the placenta. Most of the placenta is fetal tissue, so it is genetically identical with the cells of the fetus. This yields a greater amount of DNA than the sampling of amniotic fluid. These sampling techniques for pre-natal diagnosis are associated with a small increase in the risk of spontaneous abortion, compared with the risk in pregnancies not screened by these methods.

Supporters of pre-natal diagnosis point out that as the accuracy of the tests improve, there should be fewer abortions. At present, they argue, a substantial proportion of post-test abortions are normal pregnancies because the tests are not always accurate and decisions are based on estimated risk. To others, selective abortion of affected fetuses is always morally objectionable, and especially so when the disorder might not be life-threatening, as in many individuals with Down's syndrome. However, fewer than five per cent of all pre-natal diagnoses are, in fact, positive. So for the vast majority of prospective parents, pre-natal diagnosis serves ultimately to reassure them that the unborn baby is not affected by the disease in question.

The tensions and ambiguities that surround fetal testing have given rise to what has become labelled the ‘tentative’ pregancy. Some women, who know that they are due to have an ultrasound scan or other pre-natal test, may refuse to regard themselves as ‘properly’ pregnant, in case the test indicates a problem and they are faced with the decision of whether to abort or not. Merely offering testing and termination might be seen as implying that these choices should be taken up. Yet this suggests that a pregnant woman who agrees to pre-natal diagnosis should have made a prior commitment to terminate the pregnancy if she is carrying a fetus with a genetic (or other serious) disorder.

SAQ 3

Aside from offering the possibility of termination, what other purposes might a pre-natal test serve?

Answer

A couple might wish to be forewarned of the birth of a child with special needs, so they could prepare to care for their baby.

SAQ 3a

What sort of factors might influence personal decisions about abortion?

Answer

Moral, religious, financial, experience of knowing a family with the disease, and having an affected child already.

1.1.3 Genetic testing of children

Within clinical genetic services, a difference has grown up between the testing of children and the testing of adults. Sometimes the genetic testing of children is relatively uncontroversial. For example, the genetic test may simply be to confirm a medical diagnosis that has been made on clinical grounds. So a three-year-old with low weight, blocked lungs and poor digestion may be given a genetic test to see whether they have CF or not.

There are other cases where a test is used predictively for a disorder that may affect the child soon and which needs observation. For example, in a family where the dominant disorder familial adenomatous polyposis coli (FAP) is present, there is an increased risk of bowel cancer. Medical surveillance for tumours, which can be removed if diagnosed early, is often started at about 10 years of age. Pre-symptomatic testing of children to determine whether they carry the FAP gene, and hence need to be monitored, makes sense.

But we can contrast such a straightforward case of predictive testing with genetic tests for a disorder like Huntington's disease (HD), a late onset (over 40 years of age) neurological disorder, for which there is no cure, and only limited treatment. Now that a test for the gene responsible for HD is available, should children be tested?

SAQ 4

What do you think are some of the arguments against testing a child for HD?

Answer

Some that you may have thought of are: (i) testing a child prevents them making a future decision for themselves when they are an adult; (ii) confidentiality, important in the case of adult genetic test results, will be automatically overridden in the case of a child brought in for testing by his/her parents; (iii) family knowledge of the test's result might lead to a child being treated differently by his/her parents and siblings, because they might be brought up with lower expectations of themselves.

Adult uptake of the HD test has been far lower than predicted. When asked hypothetically if they would take the test, a clear majority of at-risk adults said ‘yes’: now that the test is available, only 10–15% have actually gone for testing. Hypothetical decisions about genetic testing, either for oneself or (by extension) one's children do not seem adequately to represent real attitudes to tests when they are offered.

When people request genetic testing for their children, they usually make assumptions about what the child would want if they were older, and that the information gained from a test will be of benefit to the child concerned. On the basis of previous testing programmes, neither of these points seems valid. The bottom line is that problems in adult testing for Huntington's disease seem to arise not in the context of testing, but that of the counselling session, the provision of information and the comprehension and implications of risk estimates. These problems are going to be magnified in the case of testing children.

1.1.4 Genetic testing of adults

Huntington's disease is a good example of a late-onset disorder because it is fatal, non-treatable, relatively frequent and has a strong genetic element that can be tested for. There are others that fall into a similar category, i.e. mainly relate to a single gene, such as adult polycystic kidney disease. The issues surrounding late-onset multifactorial diseases, such as diabetes and breast cancer, will be dealt with separately. To date, relatively few diseases that fall into both these categories can be tested for, but with increasing knowledge arising from the Human Genome Project, the number of tests available will rapidly increase.

1.1.5 Late-onset single-gene disorders

An individual might know that a late-onset disease such as Huntington's disease (HD) is present in their immediate family and that they might have inherited the disease gene(s). The problems of genetic testing for HD revolve around the fact that it is pre-symptomatic.

One dilemma is the long delay between testing positive and developing the clinical symptoms of the disorder in middle age. Is it better not to know and live in hope, or as one victim cried ‘get it over, I'm so tired of wondering?’ Of course, a negative test result (i.e. the person does not carry the gene for HD) could be a huge relief, but for those who are told that they do carry the HD gene, there are huge psychological and practical problems.

One of the core issues in adult testing for single-gene disorders such as HD is getting informed consent from the patient to carry out the test. One problem is what counts as ‘informed’. How much does the patient need to know about the science of genetics to make a considered decision concerning a genetic test? But there are also examples of attempts to procure a genetic test for HD without the knowledge of the patient concerned. Sometimes this involves getting children tested, but cases have been reported where psychiatrists, social workers and lawyers have tried to get a test carried out on an adult without the permission of the person concerned. There can also be strong pressure on individuals who, although they are aware they are undergoing testing, might not be exercising their own best judgement. An example is the family pressure that can force prospective parents to be tested so that they can make ‘responsible’ decisions about having children.

A related problem is that even though someone may opt out of testing for HD, they may unwillingly discover their status through a member of their family going for a test.

SAQ 5

Within a family, who do you think should be told the results of a genetic test and why?

Answer

There is no right answer here.

Do the individual's brothers and sisters have the right to information that relates to them? If a parent knows s/he is at risk and refuses to get tested, how would they feel if their adult son goes for a test for his own peace of mind and finds out he (and therefore his parent) carries the gene? Genetic information tells us about our families, whether we want to know or not.

SAQ 6

Outside the family, who might be interested in the results of the test?

Answer

Employers and insurance companies.

1.1.6 Late-onset multifactorial disorders

It is becoming clear that many, if not most, of the common diseases that affect the Western world are multifactorial disorders with some inherited genetic component. Some of the genes that render individuals susceptible to diabetes, coronary heart disease, hypertension and many cancers, including breast cancer, have been identified and can be tested now for the presence of mutations. Multifactorial disorders present a real challenge for genetic medicine. For example, while it may be true that there is a strongly inherited component to the form of diabetes which usually occurs during adolescence (type 1 diabetes), it is not at all clear what purpose genetic testing for such a component would serve in terms of health. This is because, currently, there is no way to stop the development of the disease.

In terms of some disorders, for example heart disease and cancer, susceptibility testing might allow doctors to advise particular patients to change their diet and lifestyle, to counteract the effects of their increased genetic risk. Unfortunately, what evidence there is suggests that the results of a genetic test may fix in a patient's mind that they are going to develop the disease anyway, no matter what changes they make. This ‘genetic pessimism’ means that giving patients the results of tests may be counter-productive.

Conclusion

This free course provided an introduction to studying Science. It took you through a series of exercises designed to develop your approach to study and learning at a distance and helped to improve your confidence as an independent learner.

Acknowledgements

The content acknowledged below is Proprietary (see terms and conditions) and is used under licence.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Course image: CIAT in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Licence.

All other materials included in this course are derived from content originated at the Open University.

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University