Week 1: Understanding the principles of musical scores

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 22 November 2025, 3:02 PM

Week 1: Understanding the principles of musical scores

Introduction

Welcome to the course! Over the next four weeks, you will begin to understand how music is written down, what a musical score is and what it does. You will also learn how musicians use and interpret musical scores in their work.

By the end of this course you will understand what music notation does and some aspects of how it works. You will be able to understand more about different types of music and how they are written down, and what that notation means.

This course includes some musical terms which you may not be familiar with. We have produced a glossary of terms which you may find useful. When new musical terms appear they are in bold text, and will have a definition in the glossary.

In the following video, Open University lecturers Catherine Tackley and Naomi Barker tell you a little more about what to expect from this course.

Transcript

We would like to thank the Royal Northern College of Music (RNCM) for their assistance. RNCM musicians appear by kind permission of the Principal, Professor Linda Merrick.

Before you start, The Open University would really appreciate a few minutes of your time to tell us about yourself and your expectations of the course. Your input will help to further improve the online learning experience. If you’d like to help, and if you haven’t done so already, please fill in this optional survey.

1.1 Types of musical score

What does the term ‘musical score’ mean to you? Take a look at these images of scores. Do any aspects of them look familiar to you? Do you have any idea what the music depicted in these examples would sound like?

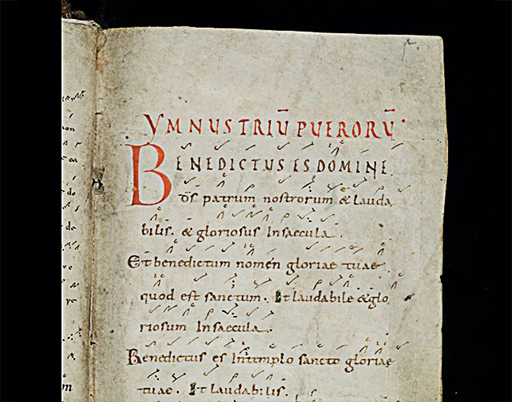

This is a photograph of a sheet of music from the middle ages.

Music from the middle ages (Figure 1) looks very different from the music of today, as it was only intended as a reminder of a melodic shape that went with words that were fully written out.

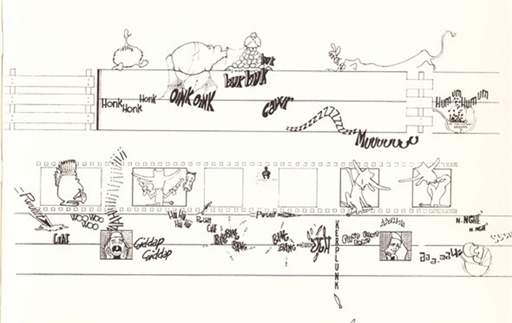

The image shows illustrations of animals and their respective noises.

Graphic notations, like the one shown in Figure 2, have been used to represent some music of very recent times. The example in Figure 2 looks like a comic strip, but represents a piece of vocal music.

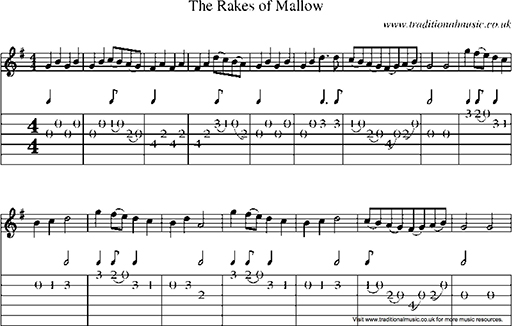

This shows the music for the song ‘The Rakes of Mallow’.

If you play the guitar or deal with popular musical genres you may have come across guitar tab (tablature), chord symbols or lead sheets as shown in Figure 3.

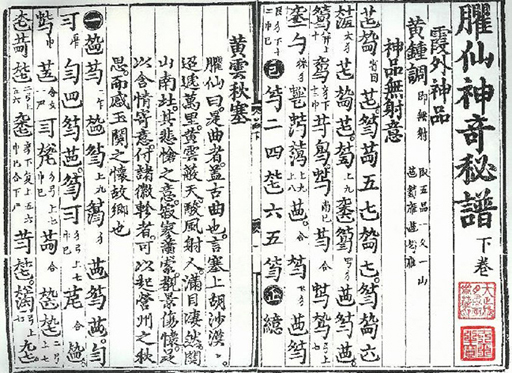

Non-Western cultures such as China and Japan have centuries-old traditions of using tablatures for writing down music that is different from those of Western music. The example in Figure 4 is a score for the qin or Chinese lute.

In Western culture we may be used to seeing scores like the final example in Figure 5, but scores are not always like this.

1.1.1 How do musical scores work?

A standard definition of a musical score is ‘a copy of a composition on a set of staves braced and barred together’ (Oxford Classical Dictionary) or staves ‘that are vertically aligned so as to represent visually the musical coordination’ (Grove Concise Dictionary of Music). Put very simply, it shows all the parts of a piece of music and how they fit together.

The function of a musical score is to document a piece of music in a written format, but many different types of notation can be used to achieve this. Look at these examples and consider how the sound and the visual representation of that sound relate to each other.

Some notations tell the reader what to do physically with fingers and hands on an instrument while others indicate a general sound structure such as a chord and expect the player to make sense of the rhythm and melody from that. Listen to the song Greensleeves. This piece of music is over 400 years old. How do you think it was written down?

The lute was very popular during the early modern period, and music for this instrument was written in a notation that presents a clear instruction to the player about where to put their fingers on which specific string of a lute. Horizontal lines represent the strings of the instrument and letters the frets. The marks over the lines are indicators of rhythm. You can view images from a digital version of the original manuscript online, by searching for William Ballet’s lute book (MS 408/1).

Modern guitar chord symbols work on a similar principle, but they only provide a suggestion of where to put your left-hand fingers, and nothing else. Other types of notation such as lead sheets, rely on the improvisation skills of the player who is expected to construct melody and rhythm from just chord indications and perhaps an outline of a known melody. These are often used jazz standards and rely on the player being familiar with the lyrics and structure of the song, and also with how chords are constructed and what they should sound like.

Now try Gershwin’s famous I Got Rhythm. Look at an image of the music for I Got Rhythm, and listen to it below.

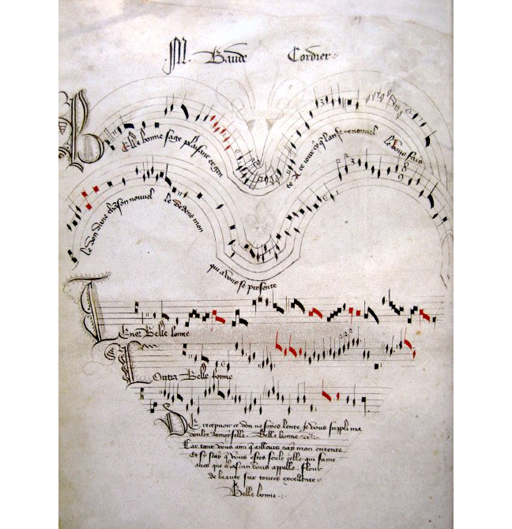

Now look at this score of a fourteenth century song, Belle, Bonne, Sage, Plaisant by Baude Cordier. What ideas do you think the writer was trying to convey in sound?

As you listen to the sound and look at the images of the notation, do you think these examples show how all the parts of the music fit together? Can you work out how what you are seeing connects with what you are hearing? Of course, they all represent sound in some way, but can you identify what particular aspects of sound? This is quite hard, so don’t worry if you can’t find anything that remotely connects sound and vision. It is precisely because it is hard that musical scores have taken several centuries to develop into the forms we now know.

1.1.2 Some things notations do

The notations featured in the previous section are all different.

The first example, Greensleeves, is in a notation that presents a clear instruction to the player about where to put their fingers on each specific string of a lute. Here, the lines represent the strings of the instrument and the letters/numbers represent the frets on the lute. The marks over the lines, are indicators of rhythm. Guitar chord symbols are similar, but they only provide a suggestion of where to put your left-hand fingers, and nothing else.

The second example, I Got Rhythm, is a lead sheet for a jazz standard. Jazz ensembles will typically construct a performance using only the lead sheet. Typically, the melody will be played by one (or more) of the musicians, while the rest provide an accompaniment based on the chords written above the melody. This will normally be followed by an improvised solo (or solos) over the chord progression.

The final example is a fourteenth century love song from the beautiful manuscript known as the ‘Chantilly codex’. The abstract representation of pitch and rhythm is the key element here. We can fathom very little about the physical aspects of performance (the ‘how to’), but it is an attempt to record the pitch and rhythm as a composer might have wanted it to sound. The shape of the notation is perhaps a poetic way of asking the performer to create a mood appropriate to a love song but does not affect the technical aspects of how it would be read.

What do you think are the primary elements of music that should be captured in any kind of notation?

1.1.3 What should a musical score capture?

In the previous section, you were asked what elements of music should be captured in a score – you may have suggested what notes to play (pitch) and rhythm as two of the most important elements.

There are of course other things that may be captured by a score, such as how loud or quiet to play, the mood of the music, what instrument to play on or words for a singer to sing – we’ll come back to some of those in later weeks.

Quite a lot of today’s music is written down after it has been composed or created, so the sounds come first, and then a written version is created from them later – this is the usual way most pop musicians work. Of course, with modern technology, writing music down from existing sounds is much easier, but in early times when there was no way of recording sound, this was a big challenge. So, how do musicians define the elements of pitch and rhythm, and how have musical scores evolved to convey them?

1.1.4 The ear-eye connection

You may not have had any experience in reading music and may never have seen an orchestral score. In the following video, which is extracted from a television series that challenged celebrities to try and conduct an orchestra, you will see Goldie, who does not read music, encounter an orchestral score. After you have watched it, think about what processes Goldie went through to understand how the score worked.

Transcript

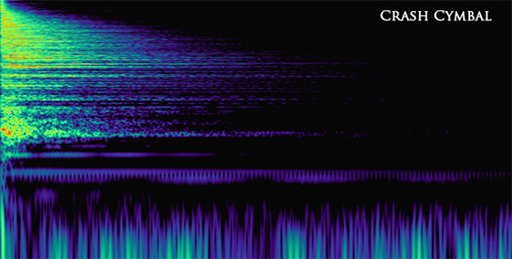

On reflecting about the video of Goldie, we hope you noticed the importance of how the visual element, the dots and lines of the score, is a representation of sound. Connecting what you see with what you hear is fundamental to understanding scores, and especially orchestral scores. Goldie achieved this connection of eye and ear by using what was familiar to him – drum ‘n’ bass sounds and rhythms – and equating them to the blocks of orchestral sound in Grieg’s piece In the Hall of the Mountain King.

We hope that you will find ways of making these connections too as you work through this course, so keep thinking about the ear-eye connections – what you hear and what you see as a representation of that sound.

You’ll be looking more closely at how conductors use scores in Week 4.

1.2 Introducing pitch and rhythm

The two primary elements of all music are pitch and duration/rhythm:

- Pitch is the term that musicians use for describing how high or how low a note is. Physicists would describe this element as frequency and measure it in cycles per second, or hertz.

- Rhythm refers to music’s temporal structure, how long or short notes are and how they are stressed.

1.2.1 A little bit of history

A notation capable of representing both pitch and rhythm evolved over a long period of time in Western history from around the tenth century to the middle of the seventeenth century, when it became fully recognisable as the notation in common use today.

It is certainly not the only notation in use, but it is the one most Western musicians will rely on as it is capable of a high level of detail. It is this detail that enables the richness of musical scores that makes them so interesting to study as composers have used this notation in so many different ways to express their ideas.

In starting to understand a musical score, the first step is to understand how both pitch and rhythm are conveyed simultaneously on a single page. Pitch occupies a vertical space. As notes go up higher and lower, they literally move up and down the stave on the vertical plane. Rhythm is about movement through time and occupies the horizontal plane, with longer and short notes having different shapes to indicate different durations of time. The synchronicity of pitch and rhythm is controlled by a beat or pulse. If you tap your foot to a piece of music, you are feeling the underlying pulse.

The earliest Western musical notation was created in monasteries to help monks remember the many chants they had to use during the cycle of the church year. It consisted of little squiggles and marks called ‘neumes’ written above words to remind the singer of how the melody went. The association with words meant that it was read from left to right, and this is how standard modern music notation works too. It is, however, not the case for all music notations. In any given culture, the direction music notation tends to follow across the page is the same as for the written script in that culture.

1.2.2 Working with neumes

To test out how neumes worked, you can try to create something similar.

Activity 1

Take a tune that you know and try to represent the shape of it using coins, stones or buttons that you can move around on a sheet of paper. See if you can put the coins down in a pattern that represents the rise and fall of the melody. This rise and fall is called the melodic contour. It’s not that easy without any point of reference. Here’s a melody (The Beatles’ Yesterday) to have a go with.

Discussion

Let’s just break that down into shorter sections and have another go.

The first little bit has three notes, short-short-long (‘Yes-ter-day’), that are all quite close to each other. What follows is a series of short notes that all move in the same direction and then just at the end fall back to a longer note (‘all my troubles seemed so far a-way’). There is another series of short notes that move down towards the start note, with another pause on a longer note (‘now it looks as though they’re here to stay’). The final eight notes of the phrase jump around a bit more, moving up and down before ending on another long note (‘oh, I be-lieve in yes-ter-day’).

Even taking this in little sections punctuated by longer notes, it is still not easy to represent accurately how high or low each note is in relation to those around it, nor how long or how short the notes might be. Bigger spaces could have been left where the longer notes are, but if you were trying to do this exercise and didn’t know the tune, it would be a bit of a guess as to just how long those notes should be.

1.2.3 Guido of Arezzo

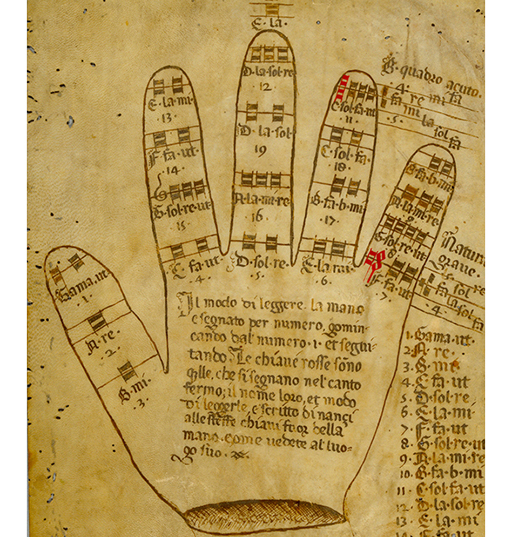

The big breakthrough in notation came around 1030 AD when the monk, Guido of Arezzo wrote a treatise called Aliae Regulae, in which he demonstrated how a single horizontal line could be drawn on the page as a point of reference for one fixed and named pitch, so that singers could relate all the other notes to it. Guido had already invented a system for reminding singers of the notes of a melody using the joints of the fingers of one hand and pointing to them with the other. You can see this original system in Figure 9.

Try drawing a line to represent the note you start on and attempt the previous activity again, putting those coins or buttons down in relation to the line. With a point of reference, you will more easily recognise how far up from the first note the melody rises and then falls back below it, and finishes by going just a little bit lower before coming back up at the end of the phrase. Figure 10 shows an attempt at this activity.

Guido later added a second, line five notes higher which made things even better as singers could relate their notes to either line. Once the idea of horizontal lines drawn on a page took off, it became the basis for all subsequent developments. All that was needed was for one line to be identified and all the others would be recognisable.

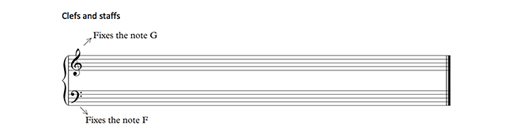

The mark that fixed the pitch of that one line became known as a clef. Rather than just two lines, our modern scores consist of a group of five lines called a staff, hence musical notation is also called staff notation. The two most common clefs (shown in Figure 11) are those that fix the note G for higher notes, called the treble clef, and F for lower notes, called the bass clef. Used together they are known as the grand staff and form the basic layout of a piano score. One other common clef indicates the position of C and is often used by instruments in middle registers.

1.3 Organising time

So far we have looked at how pitch is written down. Now, let’s look at the element of rhythm. Music exists in time and rhythm includes all the temporal elements of music. All music has rhythm. In other words, all musical sounds have definite durations and definite levels of accent. Overcoming the challenge of writing down how sounds relate to the time they occupy was a major breakthrough in the history of Western music notation.

In the following video, you will hear a discussion about some of the limitations of early notations and you’ll get to see some examples. Professor Susan Rankin talks to Open University Professor David Rowland about how difficult it was to convey both pitch and rhythm in a way that was relatively easy to learn and easy for musicians to use. You will also hear one of the earliest examples of English song – a composition that helps us to understand rhythmic notation from this time.

Transcript

1.3.1 Finding the beat

This is a photograph of four conkers and some leaves.

When a group of musicians play together, it is an element of rhythm, specifically pulse, that keeps them together. The way in which rhythm is represented in a score is crucial to a deeper understanding of it.

Rhythmic patterns are created through both note lengths, which relate to each other mathematically (half the length, twice the length, etc.), and accented notes that occur at predictable moments which we call a beat. It is often the rhythm patterns that articulate critical points in a musical score and can help our navigation and understanding of it. Repetition of patterns makes them memorable – consider Queen’s We Will Rock You or Ravel’s Bolero.

When you tap your foot to music, or dance, you are feeling the beat. Beats are grouped together in twos, threes or fours with the first in each groups being accented more strongly than the rest. The technical term for these groups is metre, but you will feel it as something like the difference between a waltz (in three time, omm-pa-pa) and a march (ONE-two-three-four). At the beginning of any piece there is a pair of numbers that looks like a fraction. This is called a time signature and the top number is a good indicator of the number of beats in a bar to expect. There are much more complicated types of metre, but you don’t need to worry about them here.

1.3.2 Close listening

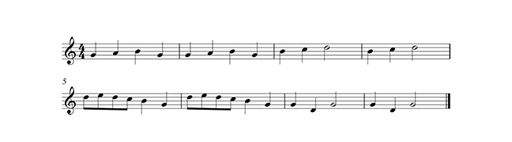

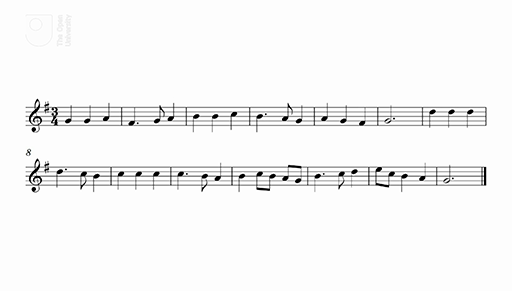

You will probably recognise this tune as Frère Jacques, but it is also the melody that forms the basis of the slow movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 1, which we will be looking at in more detail later.

You will notice vertical lines dividing up the notes. These are called bar lines. Music is divided up into bars that each contain a specific number of beats (pulses) and show the movement of the music through time. Each bar is numbered in these examples. Listen to the melody and try to tap the beat as you go. Notice where you hear longer and shorter notes and how the melodic contour moves up and down as the notes travel across the page. Listen a second time and take note of the different note shapes and other symbols.

Now listen to another equally well-known tune, Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star.

How is the pitch and rhythm of this tune similar to Frère Jacques? How is it different?

1.3.3 What are you listening for?

In the previous section, you should have noticed:

- That both tunes have a time signature that indicates four beats in a bar.

- The different note shapes in the notation – some open notes, some coloured in notes and some notes that are joined together. These indicate notes of different lengths, and being able to spot fast notes or very long notes in a score is useful to keep track of where you are on the page.

As a general rule, the blacker the notes look and the more densely they occupy the space of the bar, the faster the notes in relation to the beat. The more open and white the notes appear, the slower they are in relation to the beat.

Even more importantly, identifying rhythmic patterns can help you understand the structure of a piece of music, as rhythm is often a point of reference in a theme – just think of the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony as a case in point (if you’re unfamiliar with Beethoven’s Fifth, there is a recording of it in Week 4).

If you were listening to the contour, you will have noticed that Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star is different from Frère Jacques, in that the tune starts with a jump up from the first couple of notes and then moves steadily downwards. You will see the shape of the notes on the page – the melodic contour – looks different because of this.

Both of these tunes have patterns of notes, either pitch, or rhythm, or both, that repeat. This is something that all music does, and one of the skills in understanding scores is recognising melodies or rhythms that are the same, because repetition is often what gives a piece of music, however big, its structure and coherence.

1.3.4 Comparing notes: reading a musical score

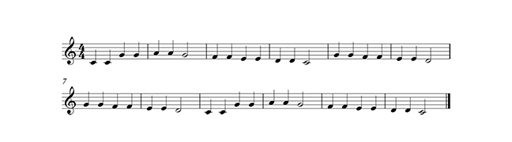

In this video, you’re going to study some simple melodies to understand more about how to follow single lines of music in a score.

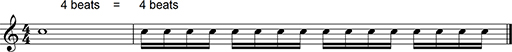

Even if you don’t read music, you can get an idea of what rhythm patterns look like by the shape of the notes. As a general rule, the blacker the notes look and the more densely they occupy the space of the bar, the faster the notes in relation to the beat. The more open and white the notes appear, the slower they are in relation to the beat. A single four beat note called a semibreve, for example, may occupy a whole bar, but in the same space of time, you may get 16 semiquavers:

Notice how these faster notes have their stems connected with a beam. These two bars of notes are mathematically equal in value in terms of the duration of their respective sounds, provided the speed of the beat doesn’t change.

When you watch this video, use what you understand about note values to help you learn to follow the scores.

Transcript

1.3.5 Single line notation in context – the bigger picture

With practice, you will get used to feeling the beat, listening for repeating rhythmic and melodic patterns and start spotting them in scores that you look at.

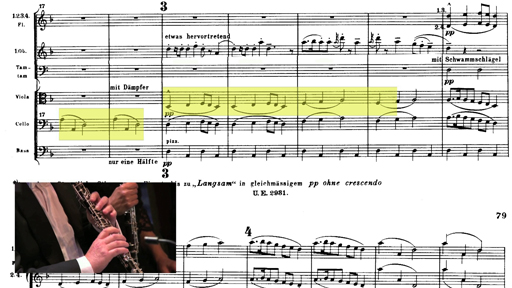

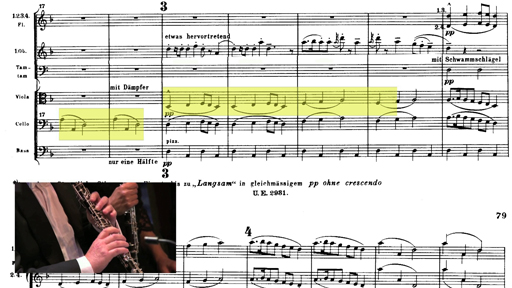

Finish the week by looking at how understanding a single line score can help you understand how much larger scores work and how the various melodies fit together. In the following video, you will be able to follow the score while you listen to a section of Mahler’s Symphony No. 1. We will look at the melody based on Frère Jacques as it appears in different parts of the score, first the double bass, then the cello, the viola and finally the flute.

1.4 Week 1 summary

This week you have looked at different types of musical score, how notation works and some historical background to modern Western music notation. You have started listening more critically to melodies, identified their contours and repeating patterns as they are represented in simple scores. You have also started building the skill of close listening and of following a score while listening to the music.

So far, we have taken a wide ranging view of musical scores, and music in different styles and from different cultures. As this is a short course, we cannot possibly discuss so many different types of music in any detail, so from now on, the focus will be on Western art music and big band jazz.

Next week, you will build on these skills and be introduced to piano scores, which have two lines of music to follow. You will also meet pianist Alexander Panfilov as he performs Mozart, and talks about how he uses a score in preparing for performance.

Images

This free course was written by Catherine Tackley and Naomi Barker.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Course image © Emir Memedovski/iStockphoto.com

Figure 1 www.e-codices.unifr.ch/ http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

Figure 2 © Reproduced by kind permission of Peters Edition Limited, London on behalf of C.F. Peters Corporation, New York.

Figure 7 © Gebre Waddell/ www.stonebridgemastering.com

Figure 12 Used with the kind permission of Denver VC Primary School

1.1.1 How do musical scores work? audio: © Dorian Sono Luminus

1.1.1 How do musical scores work? audio: © Naxos Jazz Legends

1.1.1 How do musical scores work? audio: © Harmonia Mundi

1.1.4 The ear-eye connection video: from Maestro 12 August 2008 © BBC 2008

1.3 Organising time video: © The Open University (2015)

1.3.3 What are you listening for? audio: © Warner Classics - Parlophone

1.3.5 Single line notation in context - the bigger picture video: © The Open University and its licensor(s)

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don’t miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.

References

Hornblower, S. and Spawforth, A. (2005) The Oxford Classical Dictionary [Online], Oxford, Oxford University Press, Available at Oxford Reference (Accessed 3 March 2016).

Chorlton, D. and Whitney, K. (2016) Grove Music Online [Online], Oxford, Oxford University Press, Available at http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/25241 (Accessed 3 March 2016).

Copyright © 2016 The Open University.