1.8 The end of infectious diseases?

In 1967, William H. Stewart (1921–2008), the Surgeon General of the United States of America (USA) – a role equivalent to the Chief Medical Officer in the UK – is alleged to have announced:

It is time to close the book on infectious diseases and declare the war against pestilence won.

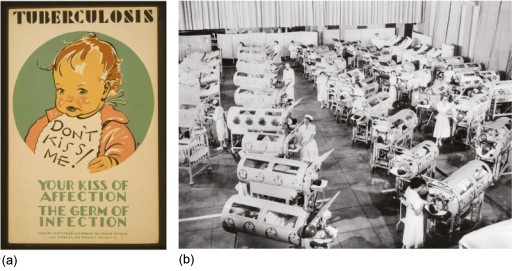

Less than 40 years before this woefully optimistic claim, at least 20 million people had died in 1918–19 from influenza, most of them young adults in the UK, USA and Europe. Public health officials in the USA in the 1940s were actively campaigning to halt the spread of tuberculosis (TB) in ways that may surprise you (Figure 11a), and in the decade ending in 1960 more than 102 000 people in the USA – many of them children (Figure 11b) – were paralysed by polio (data from Post-Polio Health International, n.d.; note that ‘n.d.’ indicates that no date was given).

So what gave public health officials like Stewart such confidence that the threat from infectious diseases was really over in 1967? The belief that infection had been vanquished in the USA and would ultimately be conquered in the rest of the world was based on the success of two innovations in medical science in the early 20th century:

- The development of new and more powerful antibiotics – a type of drug that kills bacteria, which dramatically cut the death rates in the 1950s and 1960s from bacterial infections such as pneumonia.

- Mass vaccination programmes after World War 2, where new vaccines containing substances derived from pathogens were given to children in injections or by mouth. In the 1950s and early 1960s, new vaccines gave effective protection for the first time against polio, diphtheria [dipp-thear-ree-ah], whooping cough (pertussis [purr-tuss-is]) and tetanus [tett-ann-us].

Unfortunately, Stewart was fundamentally wrong in predicting that infectious diseases would disappear as a cause of human suffering. They are still very much with us in the 21st century. New infectious diseases are emerging at an accelerating rate and pathogenic bacteria are developing resistance to antibiotics, so in some ways the threat is increasing, not decreasing as the next section briefly explains.