4.3 Leukocytes: the cells of the immune system

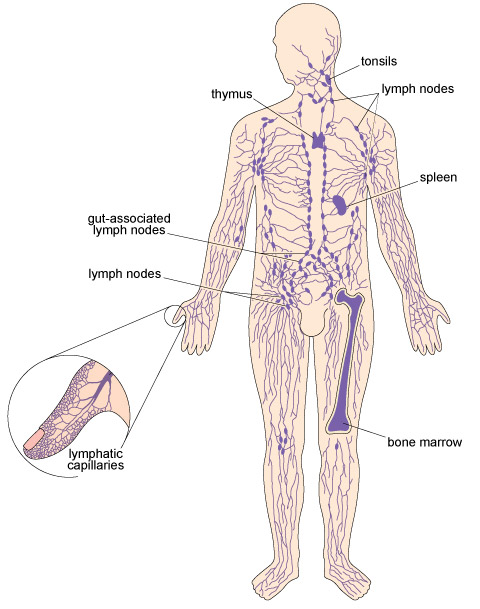

Once the barriers to infection have been breached and inflammation has begun, the active agents of the immune system, the leukocytes [loo-koh-sites], get to work. Leukocytes are often described as ‘white blood cells’ to distinguish them from the red blood cells that transport oxygen around the body; however, calling them ‘blood’ cells is misleading because leukocytes roam throughout the body tissues and only spend part of their lives in the bloodstream. In fact, they spend more time in the lymphatic system (Figure 3), the network of fine tubules that collect tissue fluid from all over the body and return it to the bloodstream.

The lymphatic system includes specialised organs and tissues where leukocytes develop. During an immune response to pathogens, we may become aware of swollen lymph nodes (popularly called ‘glands’) in the neck, armpits or groin, which enlarge when the leukocytes they contain are multiplying near a site of infection.

Leukocytes can distinguish between ‘self’, the cells and proteins generated by the organism whose body they patrol, and ‘non-self’ (or ‘foreign’) material such as pathogens that originated outside the host’s body. Leukocytes are self-tolerant, i.e. they do not normally attack the host’s own cells or body proteins, but direct their actions only against non-self material that may pose a threat.

Although we have referred to ‘the’ immune response, as if it was just one thing, in fact, there are two types of immune response, distinguished as innate and adaptive immunity.