Accessibility of eLearning

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 25 April 2024, 4:44 AM

Accessibility of eLearning

Introduction

Introduction

Accessibility to eLearning for disabled students is a topic which could be included in any area of the curriculum. Most education professionals are aware that they should consider it, but are unsure of what it means, and how to make their eLearning materials accessible to students with a range of disabilities. This free course addresses that need.

If you are interested in this topic, The Open University offers an MA in Online Teaching, which further explores accessibility in the context of online learning.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

discuss the main challenges facing disabled students with respect to eLearning.

have an understanding of the types of technology used by disabled students.

consider what adjustments you might make in creating eLearning materials to ensure they are accessible and usable.

consider appropriate ways to evaluate the accessibility and usability of your eLearning materials.

1 Introducing accessibility and disability

With the use of computers and the web becoming widespread in most parts of the world, many disabled people now could potentially have better and more independent access to information and communication. New technology developments can make this access easier, but they can also raise new barriers. These barriers can often be removed by considering the needs of disabled users when designing and implementing electronic or online educational materials.

1.1 Why is accessibility important?

Neon sign showing the words ‘Accessibility’

As common technical and physical barriers are removed, or at least lowered, people are turning towards designing eLearning courses so that students with the widest range of abilities and social circumstances can participate successfully.

These are the ideas that we are talking about when we use the term ‘accessibility’.

Experience has shown us that it is better to consider accessibility at the beginning as well as throughout a process. It is often much more difficult to incorporate accessibility after a complex product has been completed (often termed ‘retrofitting’) and may be very expensive to achieve.

As you start to look at making adjustments to course materials or to build accessible eLearning materials, questions are raised about the effect of this on the intended learning outcomes of the course or the course component in question. Education professionals need to be aware of the need to make appropriate adjustments to support accessibility and to make any decisions such that the academic content is not compromised.

For example, if you provide a description of an illustration, will the description enable a blind student to think about the subject to the same extent as a student who can see it? And in the context of the course, is this important?

As the use of information technology and web-based applications in distance teaching has increased, response to the needs of disabled students can no longer be seen as something that can be fixed bit by bit when individual students request it. In many countries legislation exists that requires all sectors to take steps to ensure that disabled people are not excluded. This anticipatory aspect applies to education too.

In this course we ask you to consider what you already know about disability from your own experience and to begin to create a list of eLearning activities that may be challenging for disabled students. You will build on this in the other activities presented in this course.

1.2 Considering disabled people

There are approximately one billion disabled people in the world – that’s around a seventh of the world’s population (World Bank, 2017). In Europe, one in seven people of working age (15–64) say that they have some form of disability (Eurostat, 2017). This can include having difficulty performing specific tasks such as walking, reading, lifting, listening or typing, and it also includes general health conditions such as cancer, bipolar disorder or arthritis.

The faces of a diverse group of people

Disabled people were among the early adopters of personal computers. They were quick to appreciate that word processing programs and printers gave them freedom from dependence on others to read and write for them. Similarly, although smaller devices like smartphones can have accessibility issues, some disabled people became early adopters due to their power for portable text-to-speech and later speech recognition capabilities. Some of these disabled early adopters became very knowledgeable about what could be achieved and used their knowledge to become independent students at a high level. They also gained the confidence to ask that providers of education make adjustments so that disabled students could make better use of course software and the web, rather than just word processing. In many countries pressure from these disabled people and their advocates has led to the creation of laws ensuring certain aspects of accessibility.

For some disability groups, information in electronic format (whether computer-based or web-based) can be more accessible than printed information. For example, people who have limited mobility or limited manual skills can find it difficult to obtain or hold printed material; visually impaired people can find it difficult or impossible to read print, but both these groups can be enabled to use a computer and, therefore, access the information electronically.

Online communication can enable disabled students to communicate with their peers on an equal basis. For example, a deaf student or a student with Asperger’s syndrome may find it difficult to interact in a face-to-face tutorial, but may have less difficulty interacting when using a text conferencing system in which everyone types and reads text. In addition, people’s disabilities are not necessarily visible in online communication systems; so disabled people do not have to declare their disability and are not perceived as being different.

The demand from disabled students may be sufficient justification for meeting their needs, but there are three main factors that motivate educators to consider the needs of disabled people in eLearning design.

1.2.1 The social and medical models of disability

Four symbols used to represent disabilities: someone sitting in a wheelchair; a brain; hands using sign language; and someone walking with a stick held in front of them

There are several models used to describe the approaches individuals and organisations take towards disabled people in general. The two most widely used are the social model and the medical model.

The definition of the medical (or individual) model …

… locates the ‘problem’ of disability within the individual and … sees the causes of this problem as stemming from the functional limitations or psychological losses which are assumed to arise from disability.

(Oliver, 1990)

In the medical model the barriers exist because of people’s impairments. In contrast, the social model describes disability as …

… all the things that impose restrictions on disabled people; ranging from individual prejudice to institutional discrimination, from inaccessible public buildings to unusable transport systems, from segregated education to excluding work arrangements, and so on.

(Oliver, 1990)

In other words it is society that disables people who have impairments (an impairment is defined as any loss or abnormality of physiological, psychological or anatomical structure or function (WHO, in Wood (1980)). The social model was developed in the context of disabled people campaigning for change in societal attitudes. The model focuses on the need for society to change policy and attitudes as well as eliminate economic discrimination against disabled people.

In reality, although we lean towards the social model more than the medical model, neither is a perfect fit for our approach to creating accessible eLearning. We should adopt the social model approach that an impairment only becomes a disability when society does not adequately cater for that impairment, and by extension, therefore, that eLearning material should be created to permit access by individuals with all kinds of impairment, but we should not forget that other factors will interplay when it comes to disabled people interacting with our materials.

1.3 The ethical and legal imperative for accessibility

The first factor to consider is ethics. Disabled people should not be excluded from using any product, device or service if it is at all possible to avoid this: disabled people have the same rights as non-disabled people to access goods and services. Teachers generally try to write material that reflects the experiences of people from diverse backgrounds, to make a course inclusive and ‘pedagogically accessible’. This good practice should be extended to include reflecting the experiences of disabled people and ensuring that there are no barriers to their participation in the course.

A sign which reads ‘Ethics’ with a graphic representation of two people - one is sitting on top of the sign and the other is behind it standing up

Supporting the ethical factor is legal obligation. In many countries it is unlawful to discriminate against disabled people as employees, as students, and as consumers of goods and services. Legislation requires employers, education establishments, and providers of goods and services to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ to avoid discriminating against disabled people.

In practice this means that, where ‘reasonable’ to do so, websites, software, buildings and other entities involved in employment, education or other services need to be made accessible. Many countries have extended this to require that the needs of disabled people should be anticipated – thus providing access beforehand, not waiting until a disabled person asks for it. This means that a provider of a service cannot justify not making an adjustment by saying that they do not have any disabled customers; they need to anticipate that they may have disabled customers in the future.

1.4 Usability and accessibility

A smiley face with the words USABILITY and EXPERIENCE encircling it

In general terms, and business terms, it is good practice to make a product available to as wide a market as possible. A design that incorporates the requirements for disabled students is likely to be more accessible and useful for non-disabled students than a design without such consideration. To design something (eLearning materials, for example) with the needs of disabled people in mind is termed ‘accessibility’. To design something to make it as easy to use as possible by all potential users, regardless of what impairments they may have or what assistive technologies they may use, is termed ‘usability’.

In practice, when designing eLearning materials, the goals of both are broadly similar. But consider one rather silly example to highlight the difference: a page of white text upon a white background could be ‘accessible’ to blind users, because their screen-reading technology will recognise the text. However it is hardly ‘usable’ by most people (and inaccessible to other groups of disabled people too). So in that case the person creating the white-text-on-white-background material could be accused of ignoring usability in favour of one very narrow aspect of accessibility. Similarly McNaught, Evans and Ball (2010) found, when testing ebook delivery platforms for accessibility with a range of disabled users, that certain tasks (such as finding and opening a particular ebook title) could sometimes technically be achieved by vision-impaired students using screen reading technology (so one could argue the process was accessible) but that in some cases it took over 150 key presses to get there (and so one could argue the process was not usable in any practical sense – particularly when a sighted person could get there with less than a dozen mouse clicks).

Mike Wald from the University of Southampton gives a few more examples of accessibility vs usability in this short video clip.

1.5 Special resources or universal design?

A person in a mobility scooter is ducking their head to drive under a fence, next to an entrance that they presumably cannot fit the scooter through

In the field of accessibility (and in particular with relation to eLearning) there exists an ongoing debate about the value of universal design (also known as design-for-all) versus the creation of alternative (or special) resources to meet particular needs. These two concepts are not opposites, and many designers of eLearning will pragmatically lean towards one and then the other as they produce their eLearning materials. Some even argue that a universal design approach can include alternative or special resources and is simply a way of saying ‘we’ve tried to cater for everyone’.

There are some instances of conflict between the needs of disability groups. Bohman (2003) describes the perceived conflict between the needs of people with cognitive disabilities and the needs of visually impaired people. The former group can find textual information challenging and may prefer pictorial representations, whereas the latter group cannot see pictures and require textual information. However, Bohman argues that a website designed for cognitively disabled people can be made accessible to visually impaired people by the provision of text alternatives to the graphics. There are, therefore, some limitations to the concept of ‘one size fits all’ but in most cases the needs of most people can be catered for without causing difficulties for other groups.

1.6 Activity 1: Anticipating needs

Before we continue to examine assistive technologies and the ways in which people interact with eLearning materials, it would be useful to undertake a short exercise to anticipate needs. Rather than reacting to the needs of disabled students who interact with our eLearning materials, it is good practice to anticipate those needs and build in as many measures as possible to enable students to work with the eLearning without problems.

Activity 1

- Identify some eLearning materials you are familiar with. You may have written them, taught them, or even studied them (you can think about this course if you have no examples of your own).

- Identify the different elements of the materials – there will almost certainly be text, but are there images, videos, forms or boxes to enter text, drag-and-drop exercises, quizzes etc.? List all of the different types of element.

- For each item on the list try to identify where students with particular disabilities might experience difficulties, and try to suggest possible ways (if you can think of any) that these barriers may be removed. It does not matter if your list is incomplete, or if you cannot think of solutions to some of your identified issues. We will revisit this task later, after you have worked through more of the course materials.

Use the box below to record your thoughts.

1.7 References

Bohman, P. (2003) ‘Web Aim: Visual vs cognitive disabilities’, in Seale, J. (2014) E-Learning and Disability in Higher Education: Accessibility Research and Practice (2nd edn), Abingdon, Routledge.

Eurostat (2017) Disability Statistics [online]. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/ eurostat/ statistics-explained/ index.php/ Disability_statistics (accessed 08 June 2017).

McNaught, A., Evans, S., Ball, S. (2010) ‘E-Books and Inclusion: Dream Come True or Nightmare Unending?’, in: Miesenberger, K., Klaus, J., Zagler, W. and Karshmer, A. (eds) ‘Computers Helping People with Special Needs. ICCHP 2010’. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 6179. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Oliver, M. (1990) The Politics of Disablement, Basingstoke, Macmillan.

Wood, P. (1980) International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps (ICIDH), Geneva, World Health Organization.

World Bank (2017) Disability Overview [online]. Available at http://www.worldbank.org/ en/ topic/ disability/ overview (accessed 08 June 2017).

2 A brief overview of assistive technology

A laptop on a table

Many disabled people use personal computers, tablets, smartphones and other devices with a wide range of adaptations, which are called assistive or enabling devices or technology. Sometimes these are adaptations to the operating system of the device, sometimes they are software solutions, and sometimes they are additional devices used in conjunction with the computing technology. In some countries there are schemes whereby students can receive financial support to buy assistive technologies for learning. There are also many free assistive technology software tools available (see below).

The benefits of assistive technology can be completely negated by poorly designed eLearning materials. We will examine ways to avoid this in Section 3. But first we need a brief overview of the kinds of assistive technologies used by people with impairments to access eLearning.

2.1 Communication aids

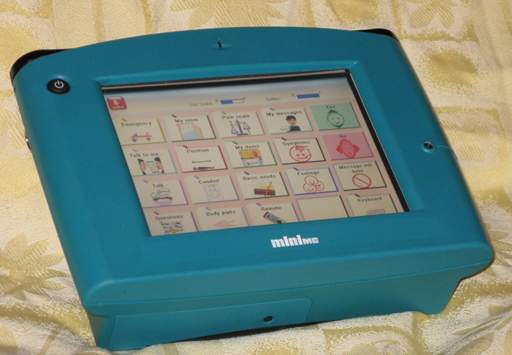

An example of a Voice Output Communication Aid

Communication aids are devices to enable those with little or no recognisable speech to communicate with others. In terms of access to eLearning these are usually pieces of hardware or software that enable regular devices to provide communication. They can produce spoken output (or spoken and text together – often called VOCAs – Voice Output Communication Aids) from text entered by the user themselves, either via a keyboard or by selecting symbols to build sentences.

This video clip shows a communication aid user talking about using these devices.

2.2 Screen readers

A laptop connected to a refreshable Braille display

Screen readers are software applications that not only read text from the screen, but also allow a user with little or no sight to navigate in a logical way via the keyboard, using auditory cues, to the information they need.

Screen readers should not be confused with text-to-speech software (see below) – their navigational capacity and auditory prompting is of little use to a user who can see the screen.

Learning how to effectively use a screen reader takes time, it is a substantial investment on the part of the user and in most cases they cannot easily switch to using another screen reader without retraining. However, once a user has become expert, they can often listen to the synthesised speech at speeds far greater than natural speech, enabling them to navigate and ‘read’ at a similar pace to sighted users.

You can watch a short video in which a screen reader user demonstrates how their software works.

Many screen readers will now operate directly from a pen drive, making the technology flexibly available to the user on any PC.

Some screen reader users prefer their screen reader to output in Braille rather than synthesised speech. A refreshable Braille display is a piece of hardware that plugs into a computer and usually sits just in front of the keyboard. When the user sets the screen reader to read some on-screen text, words appear, several at a time, on the Braille display by means of a constantly refreshing series of raised pins displaying Braille characters. This device can completely replace a screen for some users.

There are several difficulties associated with using a screen reader and speech synthesiser or Braille display to access a computer. The main one is that it is very difficult to obtain a quick overview of the information on the screen because it is presented in a ‘linear’ manner. In other words, the contents of the screen are read out word by word and there is no equivalent of the visual glance.

2.3 Text to speech

Text-to-speech software applications read selected areas of text aloud to the user, and are usually used by people with dyslexia or less severe vision impairment who can navigate by means of the visual cursor but who need help with reading longer passages of text. They should not be confused with screen readers, which offer sophisticated navigational capabilities unnecessary for most sighted users.

A person wearing a set of headphones and a microphone

Text-to-speech applications range in type from commercial software, with many additional features such as spelling and homophone checkers, to more basic free tools. In order for free text-to-speech tools to work well you need to have a high quality synthetic voice installed – synthetic voices in a variety of languages can be found online by searching for ‘SAPI5’ or ‘SAPI4’ voices.

The potential users of text-to-speech software are diverse – many people may need support with reading text from a screen, for a wide variety of reasons.

You can get a good overview of text-to-speech software from looking at a free tool called DSpeech. There are tutorials on the site, and some introductory videos can be found online.

2.4 Keyboard and mouse alternatives

An ergonomic keyboard

The mouse is the most commonly used means of accessing graphically based screens, but for some people with limited dexterity or limited vision, a mouse is very difficult or impossible to use. There are a variety of alternatives for these users, including joysticks and trackballs. Both devices allow the user to drive the cursor on screen and is useful for those with restricted, unreliable or involuntary movements. Button navigation devices and associated software allow the user to control the movement and actions of the cursor by pressing buttons to indicate the appropriate direction.

Voice recognition software can be used both for text-entry and for controlling the computer. Voice input systems include mouse emulators to allow the movement and action of the cursor to be controlled by spoken command usually in the same way as button navigation devices. Screen readers used by people with severe vision impairments and blindness operate the cursor by means of the keyboard, often using the Tab key to move between elements of a web page, for example (known as ‘Tabbing’).

Standard keyboards can also be replaced by high-visibility keyboards (often with yellow characters on black keys) for vision-impaired users, or even one-handed keyboards, which are bowl-shaped to enable the user to readily reach all keys with minimal movement.

2.5 Free and Open Source (FOSS) Assistive Technologies

The word ‘free’ in FOSS actually refers to the ‘freedom’ to use and edit the program, but it should also be available free of charge. Whilst one must always take care in downloading programs from the internet, there is a huge range of free assistive technology out there, including (but not limited to):

- Audio tools, to help you record or listen to text rather than writing or reading it.

- Display enhancement tools, to help you magnify what’s on screen or change colour or contrast.

- Planning tools, to help create visual interpretations rather than text-based ones.

- Writing aids, for example to enable those unable to use a keyboard to type using only the mouse, or to aid those with difficulty spelling or thinking of the correct word, by offering contextual suggestions.

For a comprehensive list of FOSS Assistive Technologies see Augsburg College (2017).

2.6 Other assistive technologies

A laptop on a table

The range of tools available to aid users with various impairments is enormous. Many tools are built into operating systems like Windows, MacOS, or Android – tools, for instance, to change the colour scheme or font used in online documents, to make the mouse pointer more visible, or to enable ‘sticky keys’ (a function that enables users to simulate simultaneous key presses by pressing keys one after the other, if they are unable to press more than one key at once).

2.7 References

Augsburg College (2017) Free Or Low Cost Assistive Technology For Everyone http://www.augsburg.edu/ class/ groves/ assistive-technology/ everyone/ (accessed 08 June 2017)

Some of the content of this section is drawn from materials by Jisc TechDis, a UK-based advisory service whose funding ceased in 2015 and whose website has now been taken down. It is still possible, however, to access some of the archived pages courtesy of the Wayback Machine.

3 Creating accessible eLearning content

This section of the course will help you to get started on making your eLearning materials more accessible. It may help to have some eLearning materials in mind that you want to create, or to modify, to maximise their accessibility.

3.1 Alternative content

Assistive technology can give access only to whatever is on the screen as part of the eLearning material; it doesn’t provide any alternative content, unless this is specifically added. For example, a screen reader cannot interpret visual content but it can read a description if one has been provided.

Multimedia content might need to be supplemented with the same content in other formats. Deaf students need transcripts of audiovisual content. If the video is an interview, a simple transcript may be sufficient; for more complex material the transcript may need to be synchronised with the visual flow, or provided as time-linked captions within the video frame itself.

Visual material needs to be described for blind and partially sighted people. This includes any writing presented in an image format, such as a picture of a manuscript or a newspaper cutting.

Providing alternative content can take time and the best person to do it is the author of the material. They know what the intended learning outcome is and can judge what essential information needs to be conveyed.

Alternative content can be provided in various ways; for example in web-based materials a short description can be added as an ‘ALT’ tag in the code for an image on a web page. Most screen readers will read this out automatically. A longer description could be put on a separate page and linked from the figure caption. A transcript could be displayed automatically as audio is playing or links could be offered to one or the other.

3.2 Starting with learning outcomes

A blank wooden signpost without any text written on it

The creation of accessible eLearning or online learning materials should begin with establishing the desired learning outcomes. Once we have these, we can then begin to determine different possible pathways for students to achieve them. Some of the pathways will be more accessible than others, some may require alternative content to be provided, but all should lead students to achieving the same goals. You may need to create different pathways depending upon the context of use (for example material to be used with a small cohort of known students whose needs regarding accessibility have been declared can be tailored directly towards the needs of those students, whereas material for a wider, unknown audience, such as these OpenLearn materials, must be created to meet as many potential needs as possible). David Baume (2016) produced an excellent guide to writing good (and accessible) learning outcomes.

3.3 Thinking about modes of access

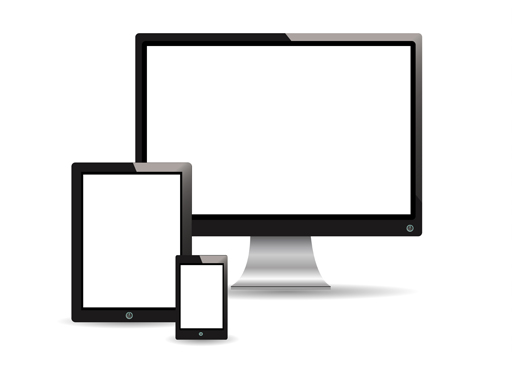

A smartphone, tablet computer, and large monitor depicted together

In addition to establishing the eLearning outcomes, early consideration also needs to be made regarding how the eLearning materials will be accessed. Are your students likely to be using PCs, or tablets, or smartphones? Will they have access to high-speed connections? Certain materials do not transpose well to smaller screens. Others do not work well on devices without a touchscreen. Still others may take an unacceptable amount of time to download on poor connections. If you are considering creating materials that will function well on handheld devices, the Jisc Mobile Learning Guide remains a very useful resource, despite being archived in 2017.

Depending upon the subject area, it may also be valuable to consider at this stage any specialist technologies the students may be expected to use with the eLearning materials. Computer-aided design packages, or software that uses specialist languages such as LaTeX, may not work or display effectively on handhld devices, and may not function adequately in conjunction with some assistive technologies. All of these things are more easily considered at the stage of creating the eLearning materials, rather than trying to make adjustments to almost-complete materials later on.

3.4 Accessible text

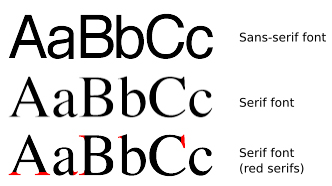

The same text written in Sans-serif font, Serif font, and a Serif font with red serifs

Here are some guidelines to consider when creating text for learners.

- For any on-screen materials, use a sans serif font. This will suit a majority of your students, especially those with dyslexia (Rello and Baeza-Yates, 2013).

- Left-align long passages of text rather than justifying them. Justified text can contain ‘rivers’ of white space due to the uneven word spacing, making it more likely that readers will ‘slip’ up or down a line and hence it slows their reading speed (Wikipedia, 2017).

- Ensure bulleted lists have a punctuation point at the end of each list item – this helps indicate to screen readers to pause briefly after each item, as one would if reading the list aloud.

- If you wish to highlight a certain passage, such as a quote, indent or use bold type, rather than using italics which are harder to read. Of course, none of these techniques will highlight the passage for screen reader users, so ensure you explain the presence of the quote in advance of the reader arriving at it.

- If you are supplying a text document for download, ensure you have used Heading Styles to denote headings and subheadings. This makes the document much more navigable (especially to screen reader users) and will also ensure that if you then convert the document to a PDF, this too will possess this accessibility feature.

- An audio version of text in your eLearning materials can greatly enhance their usability, as your students can choose which version they want to access. Audio explanations of images in particular can be very helpful.

- If you are providing PDF documents for download (a useful way to provide an alternative mode of accessing the course materials to the online version) ensure the source text or slide document is accessible according to the above points – these features (such as font and colour choice, Heading Styles and Notes field text (see below) should be carried through to the PDF document.

3.5 Accessible ‘slides’

A man giving a presentation with a flipchart

Whilst an increasing number of eLearning materials are becoming more adventurous with their presentation style, there is still a sizeable proportion of eLearning material that is rooted in Powerpoint-type presentations.

- Ensure you construct slides using the Master templates in the program you are using. The contents of the text boxes provided by the templates should be picked up by screen readers. Additional text boxes placed on the slides may not be read out automatically.

- Copy the contents of the slide into the Notes field – this ensures that additional text boxes can be read by screen readers, and gives you the opportunity to add descriptions of visual elements on the slide.

- If saving your slideset in PowerPoint or a similar program, ensure you save as a true slide format (PPTX, PPT, ODP) rather than a slideshow format (PPS, PPSX). This allows users to make whatever changes they need to the display format of the slideshow (for example text and background colour) whereas these potential changes are unavailable if the slideshow format is used.

3.6 Accessible images

A computer desktop showing a magnified version of part of the screen

Images can be a very effective way of communicating concepts to learners. It is a myth that images should not be used for accessibility reasons, as there are more benefits than disadvantages from a pedagogical perspective. However, common sense tells us that we should consider the needs of those who cannot access the images, usually through alternative text or audio to describe the image’s contents. This alternative version should convey not just a literal description of the image (for example, ‘Map of the Mekong delta’) but also the reason why the image is being used (for example, ‘Map of the Mekong delta showing the four main south-easterly channels and the location of the town of Can Tho approximately 60km from the coast on the most southerly of these channels, the Song Hau channel).

The principal issues with images apart from the provision of information in a different medium are:

- Holistic view. Imagine someone with a vision impairment who needs to use a screen magnifier – only a portion of the whole image will be within the view of the magnifier at any given time. If the image is large (such as a complex flowchart or map, for example) it may be difficult for magnifier users to get a sense of the whole, and in some cases this may be crucial (for example to appreciate the multitude ways of getting from point A to point B on the flowchart or map) – so it may be necessary to include a commentary that covers this holistic aspect of the image (this of course will benefit all learners, not just those using magnifiers or who cannot see the image at all).

- Pixelation. Images of low resolution (which are often chosen to reduce bandwidth) can become distorted and ‘blocky’ when magnified. Images of text in particular can suffer from this problem. There are magnifiers built in to most operating systems with which you can test your images, and if necessary replace them with a higher resolution version, or offer the higher resolution image as a separate download alongside the lower resolution one.

3.7 Accessible audio

Audio files can greatly increase the vibrancy of eLearning materials. Of course any audio materials need a text version alongside to make them accessible, but this does not negate the fact that audio can be much more digestible to many learners than on-screen text. A free software program called Audacity can be used very easily to create and edit sound clips (there are dozens of tutorial videos for Audacity on YouTube). Consider adding audio clips as section summaries, revision aids, or as feedback (research suggests audio feedback can aid learner engagement with the feedback process (Cann, 2014)).

A woman wearing headphones

If you don’t wish to, or cannot, use your own voice in audio clips, it is possible to use high quality synthesized speech. You can upload a document or provide a URL to the RoboBraille web resource, and it will provide for you a very high quality synthesized audio clip of your resource, in the language you specify (note: longer documents understandably take a longer time to process).

You can also use the RoboBraille site to produce DAISY audio files. DAISY uses the formatting of your document (for example the headings and subheadings you have created using Heading Styles in Word) to create a series of audio files that match the structure of your document, making the audio as readily navigable as the text document it is based upon. This can greatly aid audio users as they can easily skim through headings etc. to find the section they want to access, just as a visual reader would do with a text document.

3.8 Accessible video

A reel of video tape

Video is admittedly less simple to produce and edit than audio, but the inclusion of (suitably captioned and/or transcripted) video can greatly enhance the engagement of learners with eLearning material (e.g. Martin, 2016; Guo et al., 2014). Even a simple 30–60-second ‘talking head’ video recorded using your webcam can have a positive effect. If you deliver the video from a script, you have a ready-made transcript prepared for accessibility purposes. You can also create engaging and accessible instructional videos by use of screen capture (free tools for this are available both online and as downloadable software) – again using your script as a transcript (although be sure not to fall into the trap of saying ‘As you can see…’ – you must ensure you describe every process verbally (and therefore in the transcript too).

3.9 Quick ways to improve accessibility

A man with his arms raised in celebration after completing a cycle race

There are a few very simple things you can implement along the way that will get your eLearning materials off to a flying start in terms of accessibility.

- Ensure that resources are created to be accessible using only a keyboard (for those who cannot use a mouse) and using only a mouse (for those unable to use a keyboard). For example, you can ensure that it is possible to ‘Tab’ between items on a form, and that drop-down lists function properly by use of the keyboard alone.

- Check images (especially images containing text) for pixelation at high magnification (most operating systems now include a magnification tool) and ensure descriptions are provided and are fit-for-purpose.

- Choose colours and fonts carefully. Whilst every individual has their own needs and there is no one solution that suits everyone, certain combinations do seem to benefit a majority of users. For example, many people with dyslexia prefer a lighter text (cream or yellow) against a darker background (navy or black), and prefer a sans serif font. This will not suit everyone, however, and the best solution, if at all possible, is to allow the user to set these options themselves according to their own preference.

- Check also that colour alone is not used to convey meaning – for example if providing a response to a multi-choice question, give a green tick or a red cross, rather than simply a green dot or red dot, which may be indistinguishable to someone with colourblindness.

- Test colour contrasts, particularly between text and the background colour it sits over. There are free colour contrast checking tools available online – you should be aiming for a contrast ratio of at least 4.5 to 1 for all text items, although for longer pieces 7 to 1 is better (W3C WAI, 2008).

- Ensure your material will function with a screen reader. You can perform basic tests with a free screen reader such as NVDA. However, more comprehensive testing should be performed with experienced screen reader users if possible.

- Keep language simple where possible. Sign language users may not be fluent in a text-based language, and people with dyslexia or cognitive difficulties will also benefit from straightforward use of language. This is not to say you should not use appropriate terminology, but that the language should not be more complex than it needs to be. If your materials are in English, you may find useful resources at the website of the Plain English Campaign.

- Ensure the user has control over basic things like stopping and starting audio clips. Never include audio that starts automatically – this can create issues for those using other forms of audio output.

- Keep your design as clear and consistent as possible.

- Test your fledgling resources with as wide a variety of users as possible. This is by far the best way to check that your attempts at creating accessible eLearning materials have been successful, and that you have achieved a high degree of usability at the same time.

3.10 A process for creating accessible materials

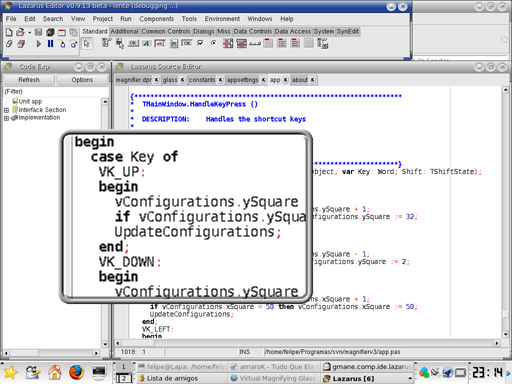

A diagram showing arrows between the words solution and problem

This is not an attempt to provide a single foolproof methodology. It is simply a suggestion for those who would like to produce accessible eLearning but who are not yet confident enough to know where to begin. There will undoubtedly be other considerations each individual educator needs to include, and there will be considerations listed here that are not appropriate in every case. Please use this list only as your starting point, as a handy guide, and do not let it constrain you in any way.

- What are your objectives in creating the eLearning material? What do you want to help your learners achieve? How will you record your decisions throughout the process, to ensure you can justify the accessibility measures you have or have not included? How will you ensure your accessible materials have not compromised academic standards or other requirements?

- Who will use the materials: a known, defined group or a wider ‘public’ group? If it is a defined group, what do you know about them that you could use to tailor your eLearning materials? How can you design your eLearning to anticipate the needs of learners who will use the materials in the future?

- How will learners interact with your materials? On which kinds of devices? On what quality of internet connections? Will they be using your materials in class, in self-directed study sessions, or in short bursts whilst at work?

- Which of the accessibility measures listed above are easily within your control? Which might need collaboration or approval from a senior staff member? How will you go about achieving those?

- Who can you contact for advice and support (and possibly funding) on the more complex elements? These may be accessibility specialists, technology specialists or disabled learners themselves.

- Where will you provide a single resource accessible to all, and where will you provide alternative versions? How will you mix and match modes of presentation to create an effective and accessible eLearning experience?

- How will you inform your students about what is available? It is not necessary to tell them about every accessibility measure you have taken, as most will simply be integral to the materials, but where alternative versions are available you need to consider how these will be signposted.

- And finally – how will you know when you’ve done a good job? How will you obtain feedback on your eLearning materials that will tell you whether your accessibility measures have been effective?

3.11 Activity 2: Creating a plan of action

Activity 2

In Activity 1 you created a list of types of interaction that might be found in a set of your eLearning materials. Now it is time to revisit that list. Did the materials in this course prompt you to think of other interactions you had missed? What about the ways in which disabled students might access your materials – add to your list any that you may have initially not thought about. Finally, consider ways in which those issues might be removed or avoided, now that you know a little more about how to create accessible eLearning.

3.12 References

Baume, D. (2016) ‘Writing and using good learning outcomes’, Leeds Beckett University. Available at http://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/ 2837/ 1/ Learning_Outcomes.pdf (accessed 08 June 2017).

Cann, A. (2014) ‘Engaging students with audio feedback’, Bioscience Education, vol. 22, issue 1, pp. 31–41. Available at https://lra.le.ac.uk/ bitstream/ 2381/ 28954/ 2/ Published.pdf (accessed 08 June 2017).

Guo, P.J., Kim, J., Rubin, R. (2014) ‘How video production affects student engagement: an empirical study of MOOC videos’. L@S ’14 Proceedings of the first ACM conference on Learning @ scale conference, pp. 41–50. Available at http://dl.acm.org/ citation.cfm?id=2566239 (accessed 08 June 2017).

JISC (2017) ‘Mobile learning guide’. Available at https://www.jisc.ac.uk/ guides/ mobile-learning (accessed 08 June 2017).

Martin, A. (2016) ‘Assessing the effect of constructivist YouTube video instruction in the spatial information sciences on student engagement and learning outcomes’, Irish Journal of Academic Practice, vol. 5, issue 1, Article 9. Available at http://arrow.dit.ie/ ijap/ vol5/ iss1/ 9/ (accessed 08 June 2017).

Rello, L., and Baeza-Yates, R. (2013) ‘Good fonts for dyslexia’. ASSETS 2013: The 15th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference of Computers and Accessibility, Bellevue, Washington USA, 22–24 October. Article No. 14. Available at http://dl.acm.org/ citation.cfm?id=2513447 (accessed 08 June 2017).

W3C WAI (2008) ‘Web content accessibility guidelines 2.0’ [online]. Available at https://www.w3.org/ TR/ WCAG20/ (accessed 08 June 2017).

Wikipedia (2017) ‘Typographic alignment: problems with justification’ [online]. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/ Typographic_alignment#Problems_with_justification Dated 16-03-2017 (accessed 08 June 2017).

4 Evaluation of accessible eLearning

People lifting up boxes, starting with one containing the word ‘poor’ and moving on to boxes containing the words ‘fair’, ‘good’ and ‘great’

It is necessary when trying to create accessible eLearning materials to be aware of any limitations to the guidelines you may be using. You may also choose to use various methods or tools to evaluate the accessibility of your eLearning materials, and therefore you also need to be aware of the advantages and drawbacks of the various ways of doing this. This section looks at these factors.

4.1 Design guidelines and their limitations

Having considered practical accessibility measures we can implement in creating eLearning materials, we now take a closer look at the guidelines that are available to support the development of accessible resources. Guidelines are available from many different sources and cover a variety of learning environments, however they are unlikely to resolve all accessibility issues in any given eLearning context, and should not be treated as a complete solution.

Coughlan et al. (2017) reviewed accessibility guidelines including the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG2.0), saying ‘Empirical studies have identified limitations in the capacity of such guidelines to ensure accessibility. For example, Power et al. (2012) found that only 50.4% of problems encountered by blind users in evaluations were covered by WCAG 2.0. Brajnik et al. (2010) found that even expert evaluators could find it difficult to reliably identify problems in websites using WCAG 2.0, or to reach shared agreement on the problems that existed.’

Coughlan et al. (2017) go on to say ‘Complementary approaches to understanding disabled users and their experiences in context are desirable. Sloan et al. (2006) outlined how contextual factors and user profiling should be represented in such approaches. Kelly et al. (2007) make recommendations for user-focused accessibility policies and processes that attend to the diversity of users, user aims, and use contexts. Building on this, Cooper et al. (2012) suggest that accessibility cannot be considered as an intrinsic quality of a resource, but that accessibility is only truly achieved with consideration of user and contextual factors.’

Despite the problems associated with the development and use of accessibility guidelines, they can be a useful tool to give developers a basic understanding of the requirements of disabled users, and should not be discounted. They should simply be used as a part of the solution for providing accessible eLearning materials, not as the entire solution.

4.2 Evaluating accessibility

A circular series of arrows linked to the word ‘Evaluation’

It is good practice to include evaluation in the development of any product or resource, but it is particularly important to evaluate accessibility because of the complex array of potential interactions between students with various needs and eLearning materials, and the associated limitations of accessibility guidelines.

Accessibility can be evaluated in two different ways.

Testing with a range of end users, and therefore in the case of testing for accessibility, with a range of disabled users.

Testing by the designer or other educators, using checklists/guidelines/automated checkers/assistive technologies.

The first approach is the best way of getting first-hand feedback from disabled users, but can be costly and time consuming to arrange, and there is no guarantee that your users will exemplify all of the potential needs of your students (Aizpurua et al., 2014). The second approach can provide ‘technical’ feedback from the perspectives of all the disability groups, but can miss the human (usability) element and can also be costly. Using automated checkers is a very limited solution and can only provide the most general of feedback, and checking with assistive technologies by people who are not expert in their use can fail to create an authentic experience (although some of the less complex assistive technologies, such as screen magnifiers, for example, can be used effectively for testing by educators not specialist in their use).

4.3 Conducting an accessibility evaluation

A written sign on a door stating ‘Usability Testing in progress. Please do not disturb’

The aim of an accessibility evaluation of eLearning materials is to assess the extent of the accessibility: not to judge whether it is or is not accessible. In other words, the question to ask is ‘To what extent is this eLearning material accessible to people with a range of disabilities?’ rather than ‘Is this accessible or not?’

Preliminary testing can be performed by the eLearning developer. Simple tests can be conducted to check the performance of the eLearning materials under magnification, in grayscale, or by using only the keyboard or only the mouse. It is also possible to check that text-to-speech tools and screen readers work sensibly with the material and that alternative versions have been provided where needed.

There are also available online some automated ‘accessibility’ checkers. These tools do not check the total accessibility of the materials, but they can give a quick indication of where issues may lie. Therefore although they should not be treated as an entire solution in their own right, they can help to save costs at the user-testing stage by identifying potential issues prior to bringing human testers into the process.

When it comes to user testing, there is guidance available to ensure you go about the process in the right way (Cooper et al., 2016; Kumar and Owston, 2016; W3C WAI, 2010). You should focus on whether or not disabled users can successfully navigate and use your eLearning materials easily (usability) more than whether the materials meet certain accessibility guidelines or checklists.

4.4 Activity 3: Working through a scenario

Activity 3

Four scenarios are presented below. Read through the four scenarios and choose one to answer the associated questions.

You will find your list from Activities 1 and 2 useful here. In a real situation, you would need to ask questions of colleagues and students, so think about what information might be missing from the scenario that you would need to find out. Think about which colleagues you might consult to find this information. Make a note in the box below of any assumptions that you make.

Scenario 1. A course with extensive audio

You are planning an eLearning activity for a modern language course. The course uses an audioconferencing system as an important tool for practising and tutoring spoken language. The tool also has a text-chat facility. Students are not assessed on their use of the conferencing but experience has shown that those who use it achieve better grades.

- Which students may have difficulty using the audioconferencing?

- What adjustments could be made?

- What alternatives could be provided?

- What information would you provide to alert students to potential challenges?

Scenario 2. A course with multimedia

You are planning an eLearning activity, which includes commissioning software that students will use to look at images, listen to audio and complete an interactive quiz. Completion of the quiz is an individual activity that counts towards assessment.

- What might some students find challenging in this activity?

- What adjustments could be made?

- What alternatives could be provided?

- Would your response be different if it was a group activity?

- What would you include in your specification to the software developers?

- What information would you provide to alert students to potential challenges?

Scenario 3. A course with extensive video

You are planning an eLearning activity that includes a DVD video. The video has a large number of short clips: some with interviews, some are situations with voice-overs and some are street scenes with background sounds but no dialogue or voice-over. Students are expected to study the street scenes in detail and to write essays about them.

- What might some students find challenging in this activity?

- What adjustments could be made?

- What alternatives could be provided?

- What would you include in your specification to the DVD developers?

- What information would you provide to alert students to potential challenges?

Scenario 4. A course with many diagrams

You are planning an extensive eLearning activity about science topics. Some of the topics use a small amount of mathematical notation and there are large numbers of diagrams and illustrations. Students are expected to study data, maps and charts and to interpret their meaning.

- Which aspects of the activity might some students find challenging?

- What adjustments could be made?

- What alternatives could be provided?

- What information would you provide to alert students to potential challenges?

There are no right or wrong answers to this activity. It is intended to help you to put into practice what you have learnt about tackling accessibility and to help you to apply the material we have presented in this course to your own situation. Of course, if you have the time, you could try to tackle several of the scenarios presented, but this is entirely at your own discretion.

4.5 References

Aizpurua, A., Arrue, M., Harper, S., and Vigo, M. (2014) ‘Are users the gold standard for accessibility evaluation?’, in Proceedings of the 11th Web for All Conference. ACM. Article 13. Available at http://dl.acm.org/ citation.cfm?id=2596705&CFID=945935323&CFTOKEN=59625762 (accessed 08 June 2017).

Brajnik, G., Yesilada, Y., and Harper, S. (2010) ‘Testability and validity of WCAG 2.0: the expertise effect’, in Proceedings of the 12th international ACM SIGACCESS conference on Computers and accessibility. ACM. pp. 43–50. Available at http://dl.acm.org/ citation.cfm?id=1878813&CFID=945935323&CFTOKEN=59625762 (accessed 08 June 2017).

Cooper, M., Colwell, C., and Jelfs, A. (2007) ‘Embedding accessibility and usability: considerations for eLearning research and development projects’, Research in Learning Technology, volume 15, issue 3 pp. 231–245. Available at http://www.tandfonline.com/ doi/ full/ 10.1080/ 09687760701673659 (accessed 08 June 2017).

Cooper, M., Sloan, D., Kelly, B., and Lewthwaite, S. (2012) ‘A challenge to web accessibility metrics and guidelines: putting people and processes first’, in Proceedings of the international cross-disciplinary conference on Web accessibility. ACM. Article 20. Available at http://dl.acm.org/ citation.cfm?id=2207028&CFID=945935323&CFTOKEN=59625762 (accessed 08 June 2017).

Coughlan, T., Ullmann, T. D. and Lister, K. (2017). ‘Understanding accessibility as a process through the analysis of feedback from disabled students’, in: W4A’17 International Web for All Conference, ACM, New York, USA., (In Press). Available at http://oro.open.ac.uk/ 48991/ 1/ Webforall17-v3-cameraready.pdf (accessed 08 June 2017).

Kelly, B., Sloan, D., Brown, S., Seale, J., Petrie, H., Lauke, P., and Ball, S. (2007) ‘Accessibility 2.0: people, policies and processes’, in Proceedings of the international crossdisciplinary conference on Web accessibility. ACM. pp. 138–147. Available at http://dl.acm.org/ citation.cfm?id=1243471&CFID=945935323&CFTOKEN=59625762 (accessed 08 June 2017).

Kumar, K.L. and Owston, R. (2016) ‘Evaluating e-learning accessibility by automated and student-centered methods’, Education Tech Research Development, April 2016, vol. 64, issue 2, pp. 263–283. Available at https://link.springer.com/ article/ 10.1007/ s11423-015-9413-6 (accessed 08 June 2017).

Power, C., Freire, A., Petrie, H., and Swallow, D. (2012) ‘Guidelines are only half of the story: accessibility problems encountered by blind users on the web’, in Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems. ACM. pp.433–442. Available at http://dl.acm.org/ citation.cfm?id=2207736&CFID=945935323&CFTOKEN=59625762 (accessed 08 June 2017).

Sloan, D., Heath, A., Hamilton, F., Kelly, B., Petrie, H., and Phipps, L. (2006) ‘Contextual web accessibility – maximizing the benefit of accessibility guidelines’, in Proceedings of the 2006 international cross-disciplinary workshop on Web accessibility. ACM. pp. 121–131. Available at http://dl.acm.org/ citation.cfm?id=1133242&CFID=945935323&CFTOKEN=59625762 (accessed 08 June 2017).

W3C WAI (2010) ‘Involving users in evaluating web accessibility’. Available at https://www.w3.org/ WAI/ eval/ users (accessed 08 June 2017).

Conclusion

By completing this free course, hopefully you are now better able to create accessible eLearning materials. You should be more aware of the range of needs of disabled students, and how they use technology and interact with eLearning materials.

You should have practiced working with your own materials and our created scenarios on accessibility to establish processes that will slot into your own workflow, and that you can practice, develop and build upon in your own context.

Accessibility and eLearning are both ever-changing fields. Technologies come, technologies go, but learners will always need access to our learning materials. Hopefully this course has helped to ensure that those students who have the good fortune to interact with your eLearning materials will have a more accessible, usable learning experience.

Keep on learning

This OpenLearn course is adapted from a course that used to form part of the Masters in Online and Distance Education qualification (H807), which has now been retired from use. If you are interested in studying how to support online learners, including accessible and inclusive education, this qualification includes further content on these topics in new and updated courses.

Study another free course

There are more than 800 courses on OpenLearn for you to choose from on a range of subjects.

Find out more about all our free courses.

Take your studies further

Find out more about studying with The Open University by visiting our online prospectus.

If you are new to university study, you may be interested in our Access Courses or Certificates.

For reference, full URLs to pages listed above:

OpenLearn – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Visiting our online prospectus – www.open.ac.uk/ courses

Access Courses – www.open.ac.uk/ courses/ do-it/ access

Certificates – www.open.ac.uk/ courses/ certificates-he

Newsletter – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ about-openlearn/ subscribe-the-openlearn-newsletter

Acknowledgements

The content acknowledged below is Proprietary (see terms and conditions) and is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

Course image: Ted Major in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Licence.

All materials included in this course are derived from content originated at the Open University.

Don’t miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University